Abstract

Objectives

Smad4 is a central mediator of transforming growth factor-β/bone morphogenetic protein signaling that controls numerous developmental processes as well as homeostasis in the adult. The present studies sought to understand the function of Smad4 expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) in vascular development and the underlying mechanisms.

Methods and results

Breeding of Smad4flox/flox mice with SM22α-Cre mice resulted in no viable offspring with SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/flox genotype in a total of 165 newborns. Subsequent characterization of 301 embryos between embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) and E14.5 demonstrated that mice with SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/flox genotype died between E12.5 and E14.5, due to decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis in the embryonic heart and arteries. Additionally, deletion of Smad4 more specifically in SMC with the inducible SMMHC-Cre mice, in which decreased cell proliferation was observed only in the artery but not the heart, also caused lethality of the knockout embryos at E12.5 and E14.5. The Smad4 deficient VSMC lacked smooth muscle α-actin filaments, decreased expression of SMC-specific gene markers, and markedly reduced cell proliferation, migration and attachment. Using specific pharmacological inhibitors and small-interfering RNAs, we demonstrated that inhibition of TGF-β signaling and its regulatory Smad 2/3 decreased VSMC proliferation, migration and expression of SMC-specific gene markers, while inhibition of BMP signaling only affected VSMC migration.

Conclusions

SMC-specific deletion of Smad4 results in vascular defects that lead to embryonic lethality in mice, which may be attributed to decreased VSMC differentiation, proliferation, migration, as well as cell attachment and spreading. The TGF-β signaling pathway contributes to VSMC differentiation and function; while the BMP signaling pathway regulates VSMC migration. These studies provide important insight into the role of Smad4 and its upstream Smads in regulating smooth muscle cell function and vascular development of mice.

Keywords: Smad4, VSMC, proliferation, migration, vasculature development

INTRODUCTION

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling controls a diverse set of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, recognition, differentiation, apoptosis and determination of developmental fate during embryogenesis and in mature tissues1. It promotes tissue growth and morphogenesis in the embryo but also activates cytostatic and cell death processes that maintain homeostasis in mature tissues. Disturbances in TGF-β signaling are thus associated with a host of developmental disorders and complex diseases2–6. TGF-β signaling promotes stabilization of blood vessels in multiple ways, including stimulating synthesis and deposition of extracellular matrix components, inducing the differentiation of mesenchymal cells to mural cells, and regulating several cellular processes in both endothelial cells and mural cells7, 8.

TGF-β signals are transduced through heterodimeric complexes of type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors. After formation of the receptor/ligand complex, the type II receptor phosphorylates the type I receptor, which in turn phosphorylates specific members of the receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads). Nearly 30 proteins have been identified as members of the TGF-β superfamily in mammals, and they can be classified based on whether they activate TGF-β-specific R-Smads (Smad 2/3) or BMP-specific R-Smads (Smad 1/5/8). Phosphorylated R-Smads associate with the co-Smad Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus to regulate transcription of target genes9–12. Smad4 encodes the only co-Smad in mammals and is a central mediator of TGF-β and BMP signaling13. Several studies using specific deletion of Smad4 in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells have shown that Smad4 plays essential roles during cardiogenesis, blood vessel remodeling, maturation and integrity14–17. Nevertheless, the precise roles of Smad4 in embryonic development and how it mediates distinct TGF-β/BMP pathways in regulating proliferation and differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) is unknown.

The initial step of vessel wall morphogenesis is the formation of a primary vascular network, comprised of nascent endothelial cell tubes, via the processes of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Subsequently, primordial VSMC are recruited to the endothelium to form a multilayered vessel wall. During the course of development and maturation, the VSMC serves as a biosynthetic, proliferative, and contractile component of the vessel wall18. As the vasculature matures, VSMC associate with arteries and veins around which they form multiple concentric layers. Thus, the presence of VSMC provides for vascular tone, control of peripheral resistance, and for distribution of blood flow throughout the developing organism19, 20.

To determine the role of Smad4 expressed by VSMC in vascular development, we generated SMC-specific Smad4 deletion mice by breeding Smad4 floxed mice with the SM22α-Cre and iSMMHC-Cre transgenic mice. Deletion of the Smad4 gene by SM22α-cre results in lethality of mice at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5), due to cardiovascular defects. Additionally, SMC-specific deletion of the Smad4 gene by the highly SMC-specific iSMMHC-Cre, which does not affect Smad4 expression in the heart, also causes embryonic lethality at mid-gestation. VSMC with the Smad4 deficiency displayed a significant reduction in proliferation, migration, cell attachment and defective actin filament structure. Using specific pharmacological inhibitors and small-interfering RNAs, we demonstrated that inhibition of TGF-β signaling and its R-Smads, Smad2 and 3, decreased cell proliferation, migration and expression of SMC-specific gene markers, while inhibition of BMP signaling only affected cell migration.

These data support an important role of the Smad4 gene and its upstream Smads in regulating VSMC phenotype and function, and thus vascular development during mouse embryogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The smooth muscle specific-Smad 4 deletion mice were obtained by crossing the Smad4flox/flox mice21 with SM22α-Cre transgenic mice, and a highly SMC-specific iSMMHC-Cre transgenic mice22. Details of materials and experimental procedures are in the Methods section in the Online Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Deletion of Smad4 in the mouse VSMC by SM22α-Cre and iSMMHC-Cre

Gene deletion of Smad4 results in early lethality of Smad4−/− mouse embryos23–25, which precludes further characterization of the role of Smad4 in VSMC in vivo. SMC-specific Smad4 deletion mice were generated by breeding Smad4flox/flox mice with SM22α-Cre transgenic mice. Male SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/+ mice were further crossed with female Smad4flox/flox mice. PCR analysis confirmed that Smad4 was efficiently deleted in SMC (Suppl. Fig 1A). Whole-mount LacZ staining for embryos from E8.25 to E11.0 of the SM22α-Cre; ROSA26 double transgenic mice showed that blue-stained cells constituted the heart and dorsal aorta from E8.25 (Suppl. Fig 1Ba to Be), whereas no LacZ staining was detected in mice without SM22α-Cre transgene (Suppl. Fig 1C). The same staining pattern between α-SMA and LacZ, as well as the equivalent intensity of LacZ-positive signals, confirming the specific and uniform expression of Cre recombinase in virtually all of the VSMC during early vascular development (Suppl. Fig 1D–1E).

Since SM22α is transiently expressed in the heart, we further determined the effect of the Smad4 deletion on vascular development by using a highly SMC-specific iSMMHC-Cre mouse model. The Smad4 deletion driven by the iSMMHC-Cre was examined using genomic DNA isolated from embryonic yolk sac as well as from embryonic heart and vessels. The data demonstrated that Smad4 was specifically deleted in the vessel, but not in the heart (Suppl. Fig 2A).

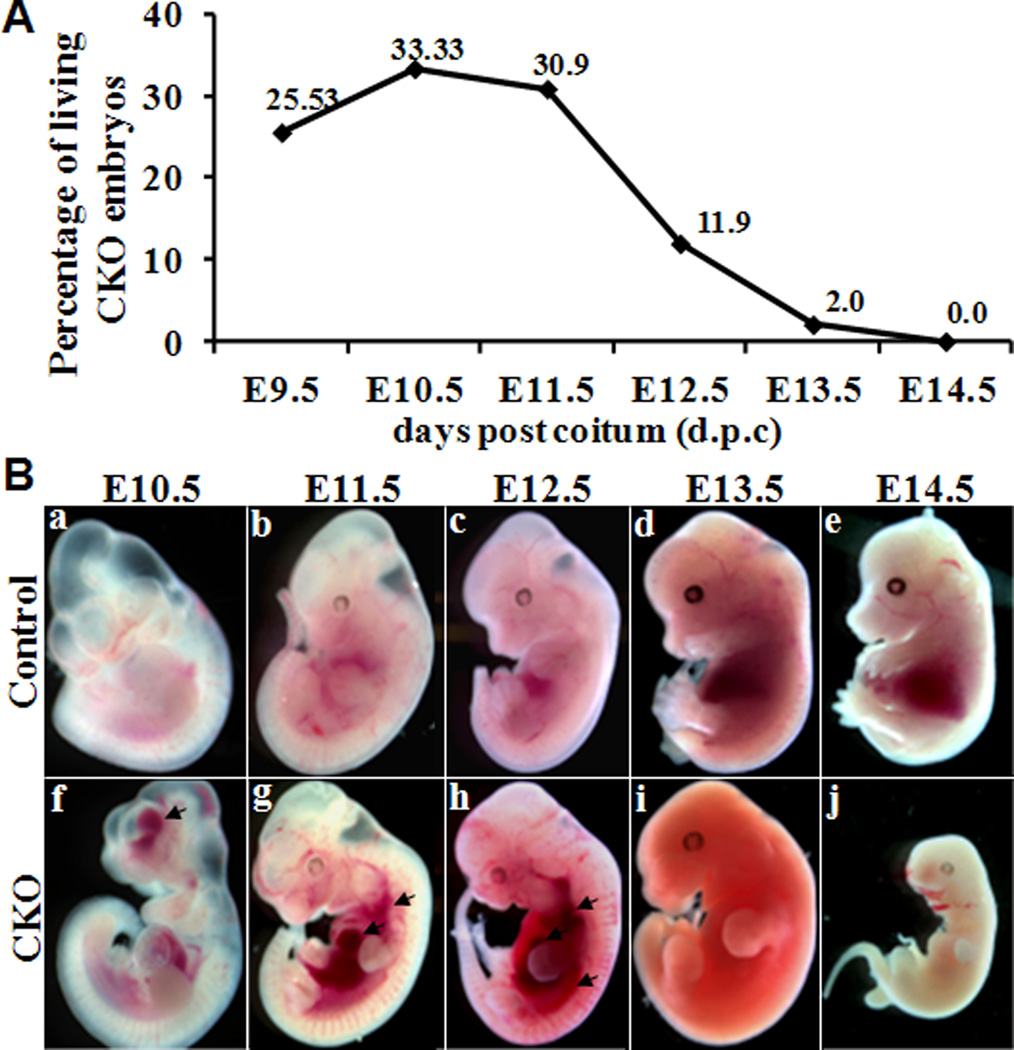

Embryonic Lethality in mice with VSMC-Specific Smad4 Deletion

We did not recover any knockout (SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/flox) neonates from the breeding of male SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/+ mice with the female Smad4flox/flox mice in a total of 165 newborn offsprings, indicating that deletion of Smad4 in VSMC causes embryonic lethality. To determine the stage at which embryonic death occurred, we examined a total of 301 pups from E9.5 to E14.5 (Table 1). The percentage of living knockout embryos between E9.5 and E11.5 was not markedly different from the expected ratio (25%), but significantly reduced at E12.5 (11.9% of total embryos) and further reduced to ~2.0% and ~0 % at E13.5 and E14.5. No knockout embryos survived beyond E14.5 (Fig 1A), indicating that the majority of embryonic lethality occurred between E12.5 and E13.5. All surviving and dead knockout embryos displayed internal hemorrhaging (Fig 1B), suggesting that the lethality was caused by vascular insufficiency.

Table 1.

Genotypes in litters from E9.5 to E14.5

| flox/wt | flox/flox | flox/wt; Cre | flox/flox; Cre | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E9.5 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 12(12) | 47 |

| E10.5 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 13(13) | 39 |

| E11.5 | 17 | 16 | 22 | 26(25) | 81 |

| E12.5 | 21 | 11 | 15 | 20(8) | 67 |

| E13.5 | 12 | 14 | 9 | 14(1) | 49 |

| E14.5 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4(0) | 18 |

| Post-natal | 43 | 53 | 69 | 0 | 165 |

Fig 1. Prevalence of the genotype in litters from E9.5 to E14.5 and morphological analysis of Smad4-deficient embryos.

All embryos were genotyped by PCR analysis of the yolk sac; and those with genotype of SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/flox were designated as conditional knockout (CKO). Gross morphological analysis of embryos from control littermates (Ba–Be) and CKO (Bf–Bj) mice at E10.5, E11.5, E12.5, E13.5 and E14.5. Knockout embryos displayed hemorrhaging as indicated with arrow in ventricle at E10.5, and in blood vessel and heart at E11.5 and E12.5, and were absorbed by E13.5 and E14.5.

As the majority of embryonic lethality occurred at E12.5 and no knockout embryo survived beyond E14.5 with the SM22α-Cre-mediated Smad4 deletion, we specifically evaluated embryo survival at E12.5 and E14.5 with highly SMC-specific iSMMHC-Cre transgene mice. A total of 55 embryos were examined. Since the SMMHC-Cre transgene is located on the Y chromosome22, we determined the survival rate of Cre-expressing male embryos. No deaths occurred in the heterozygous embryos with iSMMHC-Cre;Smad4flox/+ genotype, whereas the survival rate of the knockout embryos with iSMMHC-Cre;Smad4flox/flox genotype was 54.6% and 56.3% at E12.5 and E14.5 of the total male embryos (Suppl. Fig 2C). Similar to the observation with the SM22α-Cre mediated Smad4 deletion mice, internal hemorrhaging was displayed in the dead knockout embryos (Suppl. Fig 2B).

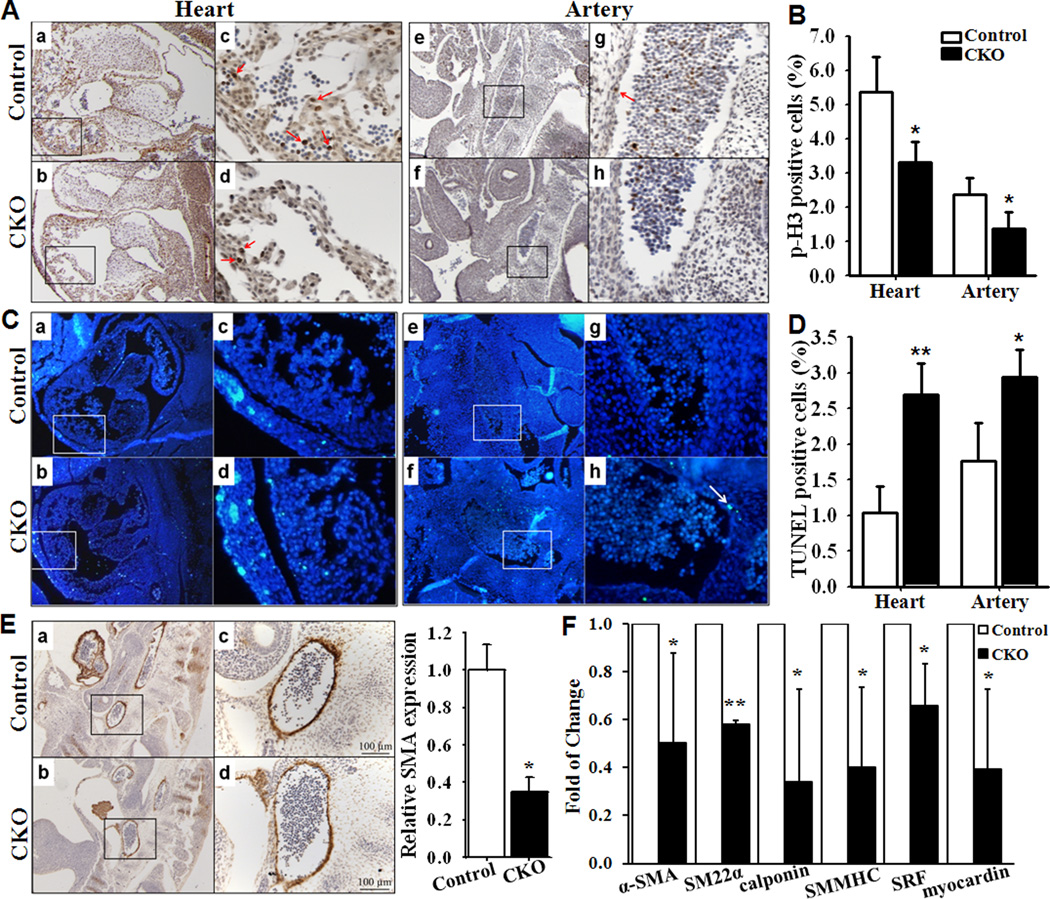

Decreased Cell Proliferation and Increased Apoptosis in Smad4 Knockout Artery

To determine the cellular mechanisms that are responsible for the vascular defects, we examined VSMC proliferation by performing immunostaining studies using a primary antibody against phospho-Histone H3. The cell proliferation rate (at E11.5) was reduced (Fig 2A) and quantitative analysis confirmed the reduction (Fig 2B) in both knockout heart and artery induced by SM22α-Cre. Similarly, a significant reduction of cell proliferation by 57% (at least 1000 nuclei of each section were counted, n=3, p<0.01 compared with that in control embryos) was found in knockout artery induced by iSMMHC-Cre. Importantly, cell proliferation was not affected in heart of iSMMHC-Cre mediated Smad4 deletion mice.

Fig 2. Smad4 depletion causes a reduction in cell proliferation, an increase in cell apoptosis and decreases in SMC marker genes.

(A) Saggital sections of control (heart: Aa, artery: Ae) and knockout (heart: Ab, artery: Af) embryo hearts at E11.5 were immunostained with a primary antibody against phospho-Histone H3 (brown, arrow). Ac and Ad correspond to the boxed regions of Aa and Ab; Ag and Ah correspond to the boxed regions of Ae and Af, respectively. (B) Quantitative analysis of the proliferation rate in heart and artery of knockout mice were compared with those in control mice (n=4, *p<0.05). (C) TUNEL analysis was performed on sections of control (heart: Ca, artery: Ce) and knockout (heart: Cb, artery: Cf) embryos at E12.5. Cc and Cd correspond to the boxed regions of Ca and Cb; Cg and Ch correspond to the boxed regions of Ce and Cf, respectively. (D) Quantitative analysis of apoptosis in the heart and artery of knockout mice were compared with those in the control mice (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).(E) Immunohistochemical analysis of the expression of smooth muscle marker α-SMA in dorsal aorta of control (Ea) and knockout (Eb) embryos. Ec and Ed correspond to the boxed regions of Ea and Eb. The expression of α-SMA in aorta of control embryos was defined as 1(n=3, *p=0.002). (F) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of α-SMA, SM22α, calponin and SMMHC as well as SRF and myocardin in yolk sacs of the Smad4 knockout mice compared to those in the control littermates (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Furthermore, TUNEL analysis demonstrated significantly increased cell death in SM22α-Cre induced knockout heart and artery at E12.5 (Fig 2C & 2D). No significant difference in cell death was identified in the heart and artery of iSMMHC-Cre mediated Smad4 deletion mice (at least 1000 nuclei of each section were counted, n=3, p=0.38 compared with that in control embryos).

Decreased Expression of Smooth Muscle Marker genes in Smad4 Knockout Mice

Immunostaining with an antibody for α-SMA demonstrated that Smad4 deletion causes a marked decrease of SMA in the dorsa aortas (Fig 2E). Furthermore, we performed real-time PCR analysis to compare the expressions of several SMC marker genes in yolk sacs from the Smad4flox/flox (control) and SM22α-Cre;Smad4flox/flox (CKO) mice. Significant reduction of the expression of α-SMA, SM22α, calponin and SMMHC, as well as the major SMC transcription factors myocardin and SRF, was observed in the knockout mice (Fig 2F).

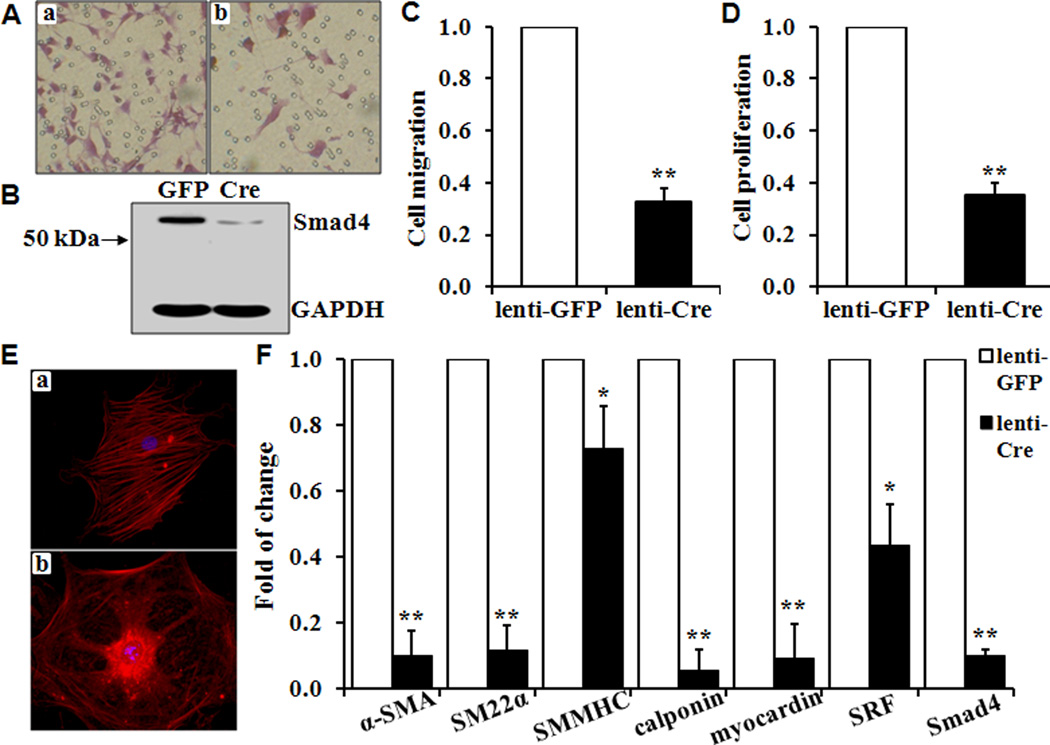

Reduced Proliferation and Migration in VSMC with Smad4 deletion

To examine whether loss of Smad4 alters VSMC function, we determined proliferation and migration in vitro in VSMC from Smad4flox/flox mice that were stably infected with lentivirus GFP or Cre. Lenti-GFP-infected control VSMC (Fig 3A, panel a) or Lenti-Cre-infected Smad4 knockout VSMC (Fig 3A, panel b) were allowed to migrate through a polycarbonate membrane within 12 hours. Quantitative analysis indicated that the Smad4 deletion in primary VSMC resulted in a significant decrease in migration induced by either 20% FBS (Fig 3C) or 20ng/mL PDGF (data not shown). Deletion of the Smad4 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig 3B). The effect of the Smad4 deletion on cell proliferation in vitro was determined by BrdU incorporation assays. BrdU labeling showed a 62% decrease in proliferation in Lenti-Cre-stably infected Smad4 knockout VSMC (Lenti-Cre) compared with the control VSMC (Lenti-GFP, Fig 3D). Similar experiments were performed with Smad4flox/flox VSMC that transiently infected with Lenti-GFP or Lenti-Cre, which also demonstrated that Smad4 deletion caused a significant decrease of proliferation to 52% (n=3) and migration to 40% (n=3).

Fig 3. Smad4 deletion inhibits VSMC proliferation and migration, decreases SMC-specific gene expression and actin filament formation.

(A) VSMC isolated from Smad4flox/flox mice were infected with lentivirus expressing GFP (Aa) or Cre (Ab), and starved in serum-free medium for 24 hours. (B) Western blot analysis to determine the expression of Smad4. Quantitative analyses of VSMC (C) Migration induced by 20% FBS; and (D) Proliferation assessed by BrdU incorporation. The migration and proliferation of control cells (Lenti-GFP) is defined as 1 (n=3, **p<0.01). (E) Actin filament formation was compared in control (Ea) and knockout cells (Eb). (F) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of SMC-specific marker genes α-SMA, SM22α, SMMHC, calponin, myocardin and SRF were determined in Smad 4 deletion VSMC (Lenti-Cre) and compared with those in the control cells (Lenti-GFP). The expression of each gene in the control Lenti-GFP cells is defined as 1 (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Decreased Expression of SMC Markers and Disruption of Actin Filament in VSMC with Smad4 Deletion

Immunofluorescent staining with an antibody for α-SMA demonstrated that the Smad4 deletion causes a marked disruption and loss of actin filament (Fig 3E). Thus, we determined the effects of the Smad4 deletion on the expression of SMC markers. Significant reduction in the expression of α-SMA, SM22α, calponin and SMMHC was observed in VSMC with the Smad4 deletion (Fig 3F). Furthermore, the expressions of the major SMC transcription factors myocardin and SRF were also decreased (Fig 3F).

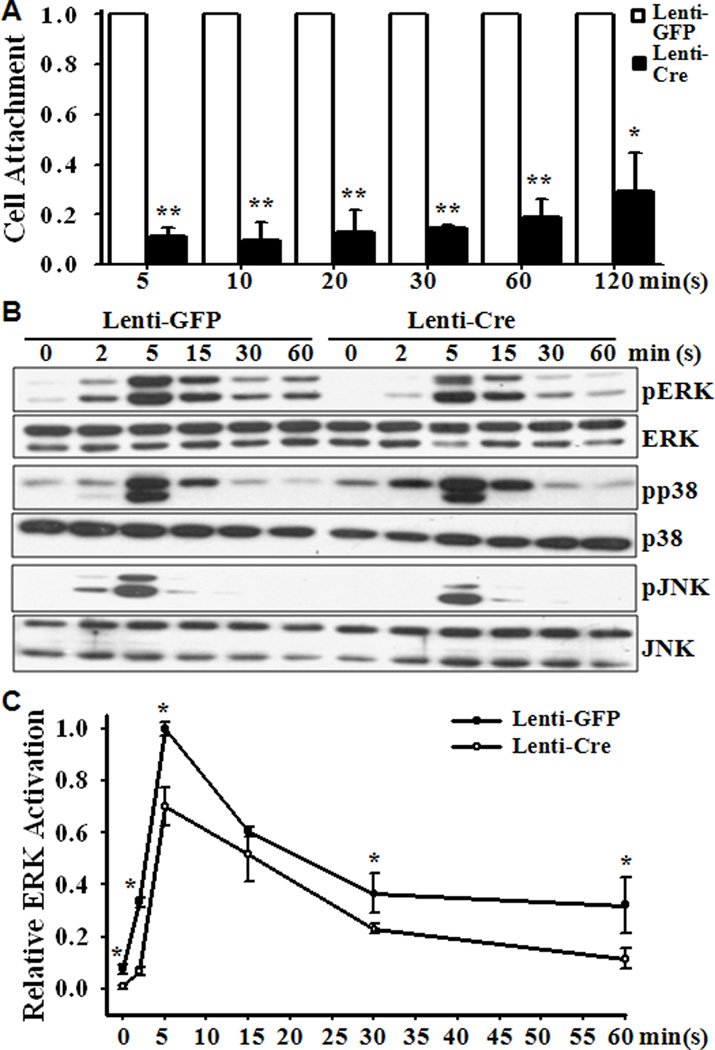

Decreased VSMC Attachment and Delayed/Decreased Activation of ERK, JNK in VSMC with Smad4 Deletion

In addition, the Smad4 deletion was found to significantly decrease VSMC attachment and spreading (Fig 4A). To characterize the possible mechanism involved, we determined the effect of the Smad4 deletion on the expression of receptors for the chemoattractant PDGF, the PDGF receptor α (PDGFRα) and PDGFRβ; as well as PDGF-activated MAPK signaling pathways. Decreased expression of PDGFRα (42.4±32.8 %, n=6, p<0.01) and PDGFRβ (65.3±16.9%, n=6, p<0.01) was demonstrated in the Smad4 deletion VSMC compared with those in the control VSMC. Additionally, PDGF was found to induce activation (phosphorylation) of ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK in control and knockout VSMC (Fig 4B). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that PDGF-induced activation of ERK, but not p38 or JNK, was significantly reduced in VSMC with Smad4 deletion (Fig 4C).

Fig 4. Smad4 deletion decreases cell attachment and delays activation of ERK and JNK.

Smad4flox/flox VSMC infected with GFP or Cre lentivirus were starved in serum-free medium for 24 hours. (A) Cells were allowed to attach to coverslips for 5, 10, 20, 30, 60 and 120 minutes, and attached cells were quantified. The attachment of control cells (Lenti-GFP) at each time point is defined as 1(n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). (B) & (C) Cells were exposed to PDGF (20ng/ml) for 0, 2, 5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes and Western blot analysis was performed with specific antibodies for ERK, p38, JNK and their respective phosphorylated isoforms. Representative blots from 3 independent experiments are shown in (B). Densitometry analysis of relative pERK/ERK is shown in (C), in which the ratio of pERK/ERK in Lenti-GFP cells at 5 minutes was defined as 1 (n=3, *p<0.001).

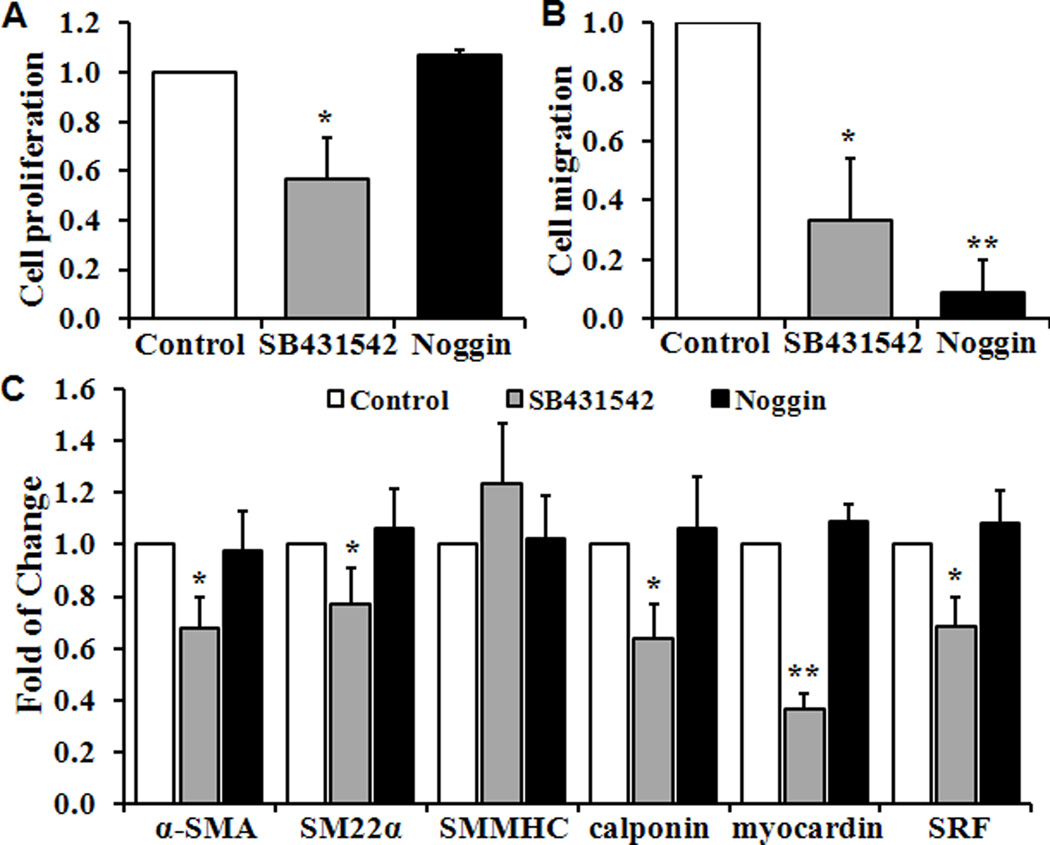

Inhibition of TGF-β or BMP Signaling Pathways on VSMC Proliferation and Migration

As Smad4 is the key mediator for both TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways, we further determined which upstream signals contribute to the function of Smad4 in regulating VSMC proliferation and migration. Pretreatment of VSMC with a pharmacological inhibitor of TGF-β, SB431542 (10µM), resulted in a 43% reduction on VSMC proliferation and 67% inhibition on migration, as well as a significant decrease in expression of SMC marker genes (Fig 5A–5C). By contrast, inhibition of BMP signaling by Noggin (100ng/ml) did not affect cell proliferation or the expression of SMC marker genes, but blocked VSMC migration by 91% (Fig 5B).

Fig 5. Function of Smad4 upstream TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways.

Wild type VSMC were pretreated with SB431542 (10µM), Noggin (100ng/ml) or control media (Control) for 48 hours. Quantitative analyses of VSMC (A) Proliferation; (B) Migration; and (C) Expression of SMC-specific marker genes by real-time PCR are shown. Cell proliferation, migration and the expression of marker genes in control condition are defined as 1 (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

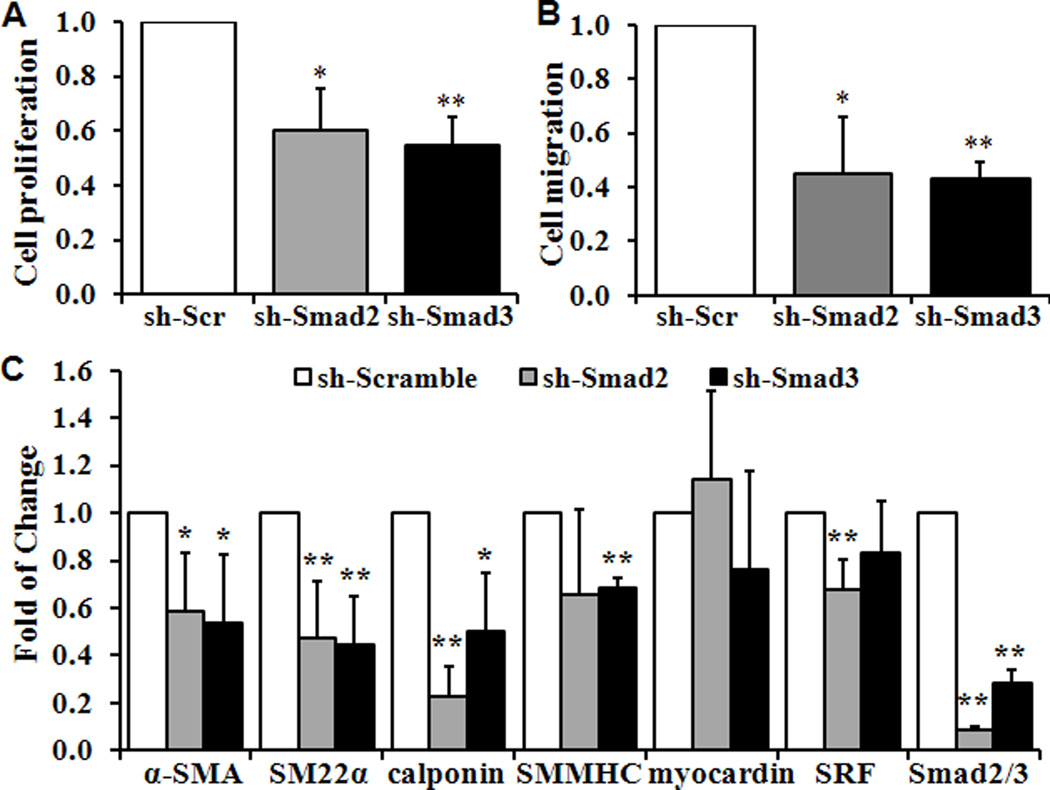

The roles of R-Smads of TGF-β signaling pathways, Smad2 and 3 were determined with the use of specific shRNA for Smad2 and Smad3. Similar to the observation using SB431542, knockdown of Smad2 and 3 significantly reduced VSMC proliferation, migration and the expression of SMC specific marker genes (Fig 6A–6C).

Fig 6. Knockdown of Smad2/3 blocks VSMC proliferation, migration and differentiation.

Wild type VSMC were infected lentivirusus carrying shRNA for Smad2 or Smad3 to knockdown Smad2 and Smad3, or control scramble shRNA. Quantitative analyses of VSMC (A) Proliferation, (B) Migration and (C) SMC-specific marker genes are shown. Cell proliferation, migration and the expression of marker genes in VSMC infected with control shRNA (sh-Scr) are defined as 1 (n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

Targeted disruption of Smad4 in mice results in early embryonic lethality with multiple defects on epiblast proliferation, egg cylinder formation and mesoderm induction25. In this study, we determined the role of SMC-expressed Smad4 in vascular development using SMC-specific Smad4 deletion mice. We found that Smad4 deficiency in SMC led to embryonic lethality at E12.5 due to cardiovascular defects, demonstrating an important role of SMC-expressed Smad4 in vascular remodeling and stabilization.

The cardiovascular system is the first organ to develop and function during embryogenesis. A functioning circulatory system is necessary for the transport of nutrients to, and the removal of wastes from, the developing organ systems of the embryo26. As the vasculature matures, recruitment and differentiation of VSMC is a critical process. VSMC provide homeostatic control and protect new endothelium-lined vessels against rupture or regression. VSMC also assist endothelial cells in acquiring specialized functions in different vascular beds and maintain vascular tone27. In the absence of these support cells, some endothelial vessels are hyperplastic, tortuous, dilated, and leaky. In a previous study, specific deletion of the Smad4 in endothelial cells caused embryonic death at an earlier time of E10.514. Our present studies using highly specific SM22α-Cre and SMMHC-Cre transgenic models have demonstrated that deletion of the Smad4 in VSMC, without disturbing endothelium (data not shown), reduces SMC proliferation and differentiation that results in vascular leakage and embryonic lethality at a later stage, E12.5 to E14.5.

The SM22α is a calponin-related protein that is expressed exclusively in smooth muscle-containing tissues of adult animals and is one of the earliest markers of differentiated smooth muscle cells28. In contrast to its smooth muscle specificity in adult tissues, SM22α was first expressed in the heart at E8.25, in the dorsal aorta at E9.5, and in skeletal muscle cells in the myotomal compartment of the somites at E10.5 as indicated with ROSA26 reporter mice used in our system, which is consistent with a previous report29. In our study, SM22α-Cre mediated deletion of Smad4 did not cause embryonic lethality in mice at such an early stage; however, significant reduction in cell proliferation and increased cell apoptosis were observed in knockout embryonic heart as compared to control littermates at E11.5 and E12.5, suggesting that transient early expression of SM22α in the heart may contribute to the embryonic lethality induced by SM22α-Cre mediated Smad4 deficiency at mid-gestation.

Using iSMMHC-Cre mice, a highly SMC-specific transgenic mouse model, we further demonstrated the function of Smad4 deletion in vasculature development. As a highly specific marker for the SMC lineage, SMMHC transcripts were only observed in blood vessels but not in developing brain, heart, or skeletal muscle30. Consistently, decreased cell proliferation was only observed in the artery but not in heart of the knockout embryos, which may explain a higher survival rate of iSMMHC-Cre-mediated knockout embryos at E12.5 and E14.5 compared to SM22α-Cre-mediated deletion of Smad4 at the same stage. Taken together, these results suggest that SMC-specific deletion of Smad4 causes vasculature defect, which leads to embryonic lethality even when heart function is not affected.

We found that Smad4 deletion in VSMC resulted in significant reduction in proliferation, migration and attachment, which may be attributed to the decreased expression of SMC-specific genes, disrupted actin filament structure, reduced expression of PDGF receptors and inhibited PDGF-induced activation of ERK. We found that smooth muscle-specific genes SM22α, calponin and SMMHC were significantly reduced in VSMC with Smad4 deletion. The principal function of VSMC is contraction and regulation of blood vessel tone, blood pressure and blood flow. In mature blood vessels, VSMC exhibit a contractile or differentiated phenotype characterized by the expression of contractile markers specific to smooth muscle, including α-SMA, SM22α, calponin and SMMHC, which are important for the regulation of contraction31. Accordingly, it is likely that loss of VSMC contraction, impaired actin filament structure, reduction of VSMC proliferation and migration due to Smad4 deficiency may be the cause of defects in blood vessel structure and function and thus result in hemorrhaging and embryonic lethality.

Several potential Smad binding sites have been identified in the promoter regions of the SMC specific genes32–34. Among the Smad proteins, Smad4, the only co-Smad, plays a critical role in TGF-β-induced SMC specific gene transcription. In addition, we found that the expression of SRF and myocardin, the key SMC-specific transcription factors, were significantly down-regulated in Smad4 knockout mice. SRF has been proposed to be a master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus35 and myocardin has been reported to be an extraordinarily powerful myogenic SRF coactivator that regulates SMC proliferation and differentiation36. Therefore, the reduction of SRF and myocardin by the Smad4 deletion in VSMC contributes to the decreased expression of SMC-specific gene markers, disrupted actin structure and reduced proliferation and migration of Smad4 deficient VSMC.

The TGF-β superfamily signaling pathways play important roles in regulating SMC differentiation8,37. Since Smad4 mediates the majority of both TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways, we further characterized which specific pathway and its corresponding regulatory Smads are important for SMC differentiation. We found that blocking TGF-β significantly decreased cell proliferation and migration as well as SMC marker expression, while only cell migration was affected by blocking BMP signaling. With the use of lentivirus shRNA specific for Smad2 and Smad3, the R-Smads of TGF-β, we have further demonstrated that TGF-β signals, mediated by Smad2 and 3, are the key upstream signals of Smad4 that regulate SMC differentiation, proliferation and migration.

Taken together, our data suggest that Smad4 participates in a complex regulatory mechanism of mid-gestation VSMC development, possibly by interacting with multiple smooth muscle-specific transcription factors. Smad4 activity is required for proper proliferation, differentiation and migration of VSMC, which is essential for embryonic vascular development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chuxia Deng (NIDDK, National Institutes of Health) for providing Smad4 floxed mice and Dr. Stefan Offermanns (Max-Planck-Institute, Germany) for the iSMMHC-Cre transgenic mice.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

YC was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health HL092215, VA Merit Review Award BX000369 and American Heart Association 0865081E.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of tgf-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz-Ortega M, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez-Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. Tgf-beta signaling in vascular fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCaffrey TA. Tgf-beta signaling in atherosclerosis and restenosis. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:236–245. doi: 10.2741/s23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massague J, Gomis RR. The logic of tgfbeta signaling. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2811–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramley F, Lorenzen J, Koellensperger E, Kettering K, Weiss C, Munzel T. Atrial fibrosis and atrial fibrillation: The role of the tgf-beta1 signaling pathway. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel VA. Transforming growth factor-beta and angiotensin in fibrosis and burn injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:471–481. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181a28ddb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebrin F, Deckers M, Bertolino P, Ten Dijke P. Tgf-beta receptor function in the endothelium. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D'Amore PA. Pdgf, tgf-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10t1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:805–814. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrana JL. The secret life of smad4. Cell. 2009;136:13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang JS, Liu C, Derynck R. New regulatory mechanisms of tgf-beta receptor function. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyazawa K, Shinozaki M, Hara T, Furuya T, Miyazono K. Two major smad pathways in tgf-beta superfamily signalling. Genes Cells. 2002;7:1191–1204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Dijke P, Hill CS. New insights into tgf-beta-smad signalling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Musci T, Derynck R. The tumor suppressor smad4/dpc 4 as a central mediator of smad function. Curr Biol. 1997;7:270–276. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan Y, Liu B, Yao H, Li F, Weng T, Yang G, Li W, Cheng X, Mao N, Yang X. Essential role of endothelial smad4 in vascular remodeling and integrity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7683–7692. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00577-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi X, Yang G, Yang L, Lan Y, Weng T, Wang J, Wu Z, Xu J, Gao X, Yang X. Essential role of smad4 in maintaining cardiomyocyte proliferation during murine embryonic heart development. Dev Biol. 2007;311:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiao K, Kulessa H, Tompkins K, Zhou Y, Batts L, Baldwin HS, Hogan BL. An essential role of bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song L, Yan W, Chen X, Deng CX, Wang Q, Jiao K. Myocardial smad4 is essential for cardiogenesis in mouse embryos. Circ Res. 2007;101:277–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hungerford JE, Little CD. Developmental biology of the vascular smooth muscle cell: Building a multilayered vessel wall. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:2–27. doi: 10.1159/000025622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SH, Hungerford JE, Little CD, Iruela-Arispe ML. Proliferation and differentiation of smooth muscle cell precursors occurs simultaneously during the development of the vessel wall. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:342–352. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199708)209:4<342::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaengel K, Genove G, Armulik A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-mural cell signaling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:630–638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang X, Li C, Herrera PL, Deng CX. Generation of smad4/dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Genesis. 2002;32:80–81. doi: 10.1002/gene.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirth A, Benyo Z, Lukasova M, Leutgeb B, Wettschureck N, Gorbey S, Orsy P, Horvath B, Maser-Gluth C, Greiner E, Lemmer B, Schutz G, Gutkind JS, Offermanns S. G12-g13-larg-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat Med. 2008;14:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu GC, Dunn NR, Anderson DC, Oxburgh L, Robertson EJ. Differential requirements for smad4 in tgfbeta-dependent patterning of the early mouse embryo. Development. 2004;131:3501–3512. doi: 10.1242/dev.01248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirard C, de la Pompa JL, Elia A, Itie A, Mirtsos C, Cheung A, Hahn S, Wakeham A, Schwartz L, Kern SE, Rossant J, Mak TW. The tumor suppressor gene smad4/dpc4 is required for gastrulation and later for anterior development of the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:107–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X, Li C, Xu X, Deng C. The tumor suppressor smad4/dpc4 is essential for epiblast proliferation and mesoderm induction in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3667–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noden DM. Embryonic origins and assembly of blood vessels. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1097–1103. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solway J, Seltzer J, Samaha FF, Kim S, Alger LE, Niu Q, Morrisey EE, Ip HS, Parmacek MS. Structure and expression of a smooth muscle cell-specific gene, sm22 alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13460–13469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Miano JM, Cserjesi P, Olson EN. Sm22 alpha, a marker of adult smooth muscle, is expressed in multiple myogenic lineages during embryogenesis. Circ Res. 1996;78:188–195. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miano JM, Cserjesi P, Ligon KL, Periasamy M, Olson EN. Smooth muscle myosin heavy chain exclusively marks the smooth muscle lineage during mouse embryogenesis. Circulation research. 1994;75:803–812. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owens GK. Regulation of differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:487–517. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen S, Kulik M, Lechleider RJ. Smad proteins regulate transcriptional induction of the sm22alpha gene by tgf-beta. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1302–1310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi K, Tazunoki T, Okada T, Ohgami K, Miwa T, Miki A, Shibata N. The 5'-flanking region of the human smooth muscle cell calponin gene contains a cis-acting domain for interaction with a methylated DNA-binding transcription repressor. J Biochem. 1996;120:18–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min BH, Foster DN, Strauch AR. The 5'-flanking region of the mouse vascular smooth muscle alpha-actin gene contains evolutionarily conserved sequence motifs within a functional promoter. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16667–16675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miano JM, Long X, Fujiwara K. Serum response factor: Master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C70–C81. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D, Chang PS, Wang Z, Sutherland L, Richardson JA, Small E, Krieg PA, Olson EN. Activation of cardiac gene expression by myocardin, a transcriptional cofactor for serum response factor. Cell. 2001;105:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah NM, Groves AK, Anderson DJ. Alternative neural crest cell fates are instructively promoted by tgfbeta superfamily members. Cell. 1996;85:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.