Abstract

Youth can be ‘powerful catalysts’ in their own and their community's development. The paper describes the experience of youth based on their participation as decision makers in and implementers of a community-based research project in a Palestinian refugee camp of Beirut, Lebanon. In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 youth and 10 of their family members or friends. The participants were asked to describe the reasons they joined the project, why they stayed on, what they liked most/least about the project, how the project influenced their lives and what they would change about the project. Thematic analysis identified recurrent themes. Youth joined the program because of its benefit to children and their community. They stayed with the program because of the solidarity they found with the team and because of their relationship with the children. They perceived that they had an important role to play in the project's success. Youth acknowledged all the skills they gained from the project. Focus groups with others corroborated their statements. This project confirmed that youth can be powerful change agents in their own development and that of their communities. An Enabling Attributes Model is proposed for projects that aim to actively engage youth as community catalysts.

Introduction

Recently, the approach to youth health and development has taken a turn from the traditional view of youth as victims or problems of society and passive recipients of adult directed interventions to one that portrays youth as contributing to community change by acting as resources and competent citizens in their communities [1, 2]. The latter perspective is supported by the Community Youth Development (CYD) approach which views young people's involvement as vital to their own development and that of their communities [3–6]. CYD emphasizes the role of youth as engaged partners: ‘CYD is defined as purposely creating environments that provide constructive, affirmative and encouraging relationships that are sustained over time with adults and peers, while concurrently providing an array of opportunities that enable youth to build their competencies and become engaged as partners in their own development as well as the development of their communities’ [5]. This approach considers youth as ‘powerful catalysts’ in their communities who are capable of working with adults as partners to make these communities safer and more prosperous [3, 4]. In return communities contribute to building young people into competent adults by providing them with opportunities to connect with others [7] and to develop their skills to lead satisfying lives as youth and later as adults. This is possible because they gain the competence to earn a living, engage in civic activities and participate in social relations [5]. A review of different community-based initiatives shows a variety of strategies used by youth to change their communities, such as conducting needs assessments [7], mobilizing children and adults, organizing grass roots groups and carrying out awareness campaigns [2, 8].

The literature on youth civic engagement and volunteering provides additional support for the benefits of youth engagement [9–13], as well as reasons that youth choose to engage in projects in their communities. Characteristics of youth more likely to become volunteers have also been assessed. Interestingly, ‘personal experience with injustice’ has been found to encourage activism [9, p. 715]. Four main reasons for engaging have been identified: (i) enhanced feelings of belonging to a community (yearning for a community), (ii) feeling psychologically stimulated, (iii) experiencing improved efficacy as a result of learning new skills and (iv) contributing to integrity for themselves and their communities [9, 10]. A variety of benefits to participation have also been identified including improved academic performance, enhanced prosocial attitudes, development of a sense of self, acquisition of a new skill set and an opportunity to explore career opportunities [11, 14]. The literature has also identified program characteristics that maximize benefits to youth. These include activities that provide opportunities for (i) youth autonomy and decision making, (ii) collaborative work with youth and adults, (iii) reflection, (iv) psychological engagement and (v) building competence, confidence, character, connection and caring [11–14].

Youth engagement has also occurred through mentoring programs. Mentoring programs have flourished in the United States and include programs such as Big Brother/Big Sister. Many programs have assessed benefits and impact on the mentee [15] with less focused on the benefits to mentors. Mentor programs have also been established in universities pairing college students to at risk youth. These programs have documented both benefit to the mentors and the mentees. One evaluation of mentor programs in 6 universities indicated that the mentors increased their self esteem and their satisfaction with their social skills [16]. The ability of mentors to impact mentees has been associated with many variable including adequate training, mentor self efficacy, frequency of contact and relationship closeness [17]. This paper adds to the literature on youth as change agents by providing insight from youth on their experiences as part of a community-based mental health intervention in a Palestinian refugee camp, which engaged them as mentors. To date, the literature on CYD, on youth volunteering, and on mentoring has been focused on industrialized countries and has not focused much on youth in a mentoring capacity to younger children [12]. The paper discusses the benefits of youth engagement as mentors as seen by themselves and significant others in their lives, in a non-industrialized world, refugee context. An emerging framework that portrays ways to enhance youth mobilization in community capacity building is then suggested.

Background and research study

The Borj El Barajneh (BBC) Palestinian refugee camp, where the community-based research intervention took place, is the sixth largest of the 12 official camps established in Lebanon to house Palestinian refugees after 1948. BBC lies in the southern suburbs of Beirut, the Lebanese capital and houses approximately 14 000 to 18 000 residents over an area of 1.6 km2 [18, 19]. Palestinian refugees in Lebanon live under dire environmental and social conditions. These conditions are commonly perceived to be the worst of Palestinian refugees in the region—exacerbated by state imposed restrictions on employment and opportunities to seek education [20]. Young Palestinian refugees in general feel discrimination from their Lebanese counterparts as well as the Lebanese state [21]. Health and social services are provided to the refugees by a variety of international as well as governmental and non-governmental organizations—but are unable to meet the needs.

Qaderoon meaning ‘we are capable’ is a theory-based youth mental health intervention project with 10–14-year-old Palestinian refugee children who live in the camp. The theoretical frameworks guiding the intervention were the Ecological Model of Health Promotion, Social Cognitive Theory, Positive Youth Development and Community-Based Participatory Research [22–24]. The research intervention tests the impact of a skills-building intervention on improving the mental health of the children. It is composed of three components, one focusing on children and two complementary interventions with the youth's parents and teachers. Specifically, the youth intervention consists of 45 skills-building sessions designed to improve communication skills, problem-solving abilities, self-esteem and self-responsibility. The intervention package was delivered in 2008–09 by 6 university level facilitators with experience working with youth and with academic backgrounds in public health, psychology or education. The facilitators were assisted by 23-Palestinian-young men and women, 17–25-year olds, who live in or around the camp community and who were trained for the role of Youth Mentors (YMs). These YMs were selected and hired to work (for nominal pay) on the intervention from 40 originally interviewed and trained.

The selection of the 23 mentors was a joint decision of the master trainer, the community field coordinator, and research team members. The interactions of mentors with their peers and with the trainer, as well as their communication styles, and interaction in role plays, were observed closely during the training describe below, and was the basis for selection of the final group of mentors. Because the selection criteria were made clear to all those participating in the training and members of the community coalition that guided Qaderoon from its inception, and because a community member (the field coordinator) was involved in the selection, community relations were maintained.

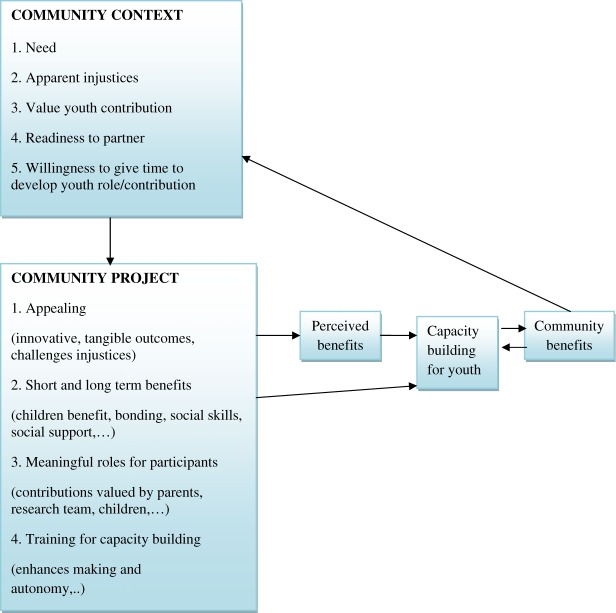

The training program for youth mentors (YMs) was extensive and included the 40 youth mentors (YMs) originally recruited. Observations and interactions during the training workshops identified some recruited youth that were not judged to be competent for the role of youth mentor as a result of difficulty in interpersonal interactions or impatience with working with children. The training began with a three day workshop prior to the initiation of the intervention. Topics included (i) the background to the project, (ii) the role of mentors and facilitators including division of tasks, code of conduct; (iii) facilitation skills and training tools such as how to conduct a game or exercise, how to deliver a message and communicate effectively, how to use the training materials; (iv) information of child development and how to deal with different styles and personalities of children, (v) ways to interact with children; (vi) a sessions-by-session review of the intervention activities; (vi) the importance of documentation and monitoring and evaluation; and (vi) logistic and administrative issues regarding lines of communication between the field team and the research team. The mentors were then observed during the intensive two-week summer program and provided with feedback regarding their performance as well as a follow-up one-day workshop prior to the initiation of the rest of the intervention. This follow-up workshop focused on problematic issues identified in the first two weeks including teamwork spirit and dynamics, giving and receiving constructive feedback and a clear allocation of tasks. The self evaluation of mentors as well as their observation by the research team and master trainer suggested that additional training on managing the relationship between the mentors and the children was needed. Strategies for constructive communication were stressed. As the intervention program progressed, 3 training of trainers sessions on specific techniques in art therapy were also provided to the mentors about one week prior to their implementation in the intervention with children. The training sessions were developed with the intent to build capacity of the YMs to become autonomous in decision making, to work collaboratively with others, to reflect, and to build character and confidence all with the intent of maximizing benefit for the youth of participating in this project. The training itself is a key component in the conceptualization of the Enabling Attributes Model suggested above (figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The Enabling Attributes Model for youth engagement.

The Qaderoon intervention was evaluated through a rigorous impact and process evaluation. The evaluation design was developed to assess changes in the children who participated in the activities. As Qaderoon progressed however, it became obvious that the mentors themselves were also greatly impacted by their involvement in this project. The aim of the current study, therefore, was to assess the benefits of participating in this project for the YMs themselves.

Methods

The researchers who had different levels of involvement in the planning and implementation of the Qaderoon project conducted this evaluation with the YMs. They adopted a qualitative research design, which allows the researcher to obtain an insider's view of the lives and experiences of the people in the study [25, 26]. The researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 18 YMs (11 young women and 7 young men) in the Qaderoon center in the camp to assess their views on and perceptions of the effects that Qaderoon had on them. The researchers also conducted interviews with 10 family members and friends of the YMs whom the YMs identified as most able to describe the changes they had passed through. After explaining the research project, informing participants of their rights and obtaining consent, the researchers conducted the interviews in colloquial Arabic. The interviews followed a relevant interview schedule—informed by the CYD literature—which consisted of a series of open ended questions about reasons they joined, why they stayed on, what they liked most/least about the project, how the project influenced their lives and what they would change about Qaderoon if it were repeated. Data collection started in April 2009 and continued till June 2009. The interviews were tape-recorded after the consent of the participants and later transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist.

The data collected were analyzed using grounded theory [27] guided by thematic analysis. In thematic analysis, the researcher seeks themes that emerge from the interview narratives, an ongoing process that requires the researcher to detect recurring issues and patterns from the data rather than from predetermined codes [25]. Recurrent themes and sentences emerging from raw data were identified and summarized on spreadsheets for data management by the research team. The researchers were guided by emerging themes rather than their interests and the analysis was grounded in the patterns that presented themselves and were verified by at least two of the research team after reading and discussing the transcripts. In the Results section, the number of interviews where the themes occur is written. The American University of Beirut Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Background information on participants

Nearly all of the YMs knew each other a little before the project and two were sisters. Four were still in school at the time they were interviewed, six were university students and one was studying in a local technical college. Four had finished their university degrees and two their vocational training. Twelve have previous experience with children through tutoring or volunteer work in NGOs carrying out fun/entertaining activities for children (e.g. games, drawing and handicrafts) and summer camps. Four YMs were part of the pilot project of Qaderoon in Shatila, another Palestinian camp nearby. Three of them were part of the process of community engagement from the beginning of this participatory initiative (2003). Of the 23 originally shortlisted and recruited to be YMs, 18 remained and contributed to the project till the end.

The YMs were responsible for assisting the facilitators by providing support in delivering the skills-building sessions to the children. They provided logistical support during the sessions and assisted in preparation of the material for each session, they followed up and escorted the children during the activities. They interacted with children and encouraged them to participate. The YMs also had a role in documentation as well as monitoring and evaluation by filling the required process evaluation forms, conducting the satisfaction exercise and providing feedback to the project team member and the facilitator on the sessions’ progress. They were specifically seen as the liaison between the children and the facilitators because they come from the same context as the children and because they are closest to them in age. The intent was that the YMs progressively take on more responsibility, and by the end of the year, they were taking charge of the sessions as facilitators.

Results

Several themes emerged from the analysis: reasons why YM joined the program, reasons for staying, their perceived contribution and role, the benefits they gained and their views on the future. Each finding will be described more fully in what follows.

Reasons for joining: benefits to the children and the community

There are several reported reasons that motivated the YMs to join Qaderoon and which were appealing to them and attracted them to the project. The recurring themes pointing to incentives for joining Qaderoon included: a variety of ‘new opportunities’ for the mentors themselves (15/18), such as a stable income for the duration of the project and an opportunity to be involved in social work. Another strongly recurring theme was the opportunity to work and interact with ‘Palestinian children in the camp’ (16/18). They reported that once they knew that Qaderoon aimed at improving the children's well being and providing them with life skills to communicate effectively with others around them, they were eager to join. Those who had such previous experiences working with children in summer camps for example expressed their interest to have the chance to do it again. In the mentors’ views, the camp is an underserved and deprived community in need of such interventions and the intervention would have possible positive effects on the children (15/18). The project was described as having potential to intervene in children's lives and to influence them for the better, while they are still impressionable.

What I liked about the project is that it involves helping the children in the camp. I passed through problems and situations when I was young and I don't want my little brother or cousin or neighbor to commit the same mistakes I did previously. (Male YM 2)

I liked the children more than anything in the project. I liked the children a lot. I felt that I was benefiting someone. Really for the first time I feel that I am doing something for someone, that is someone in need. I'm doing something good for the camp. (Female YM 4)

Reasons for staying: ‘we're in it together’

All of the YMs expressed their overall content with the project, with the aim or the design and with the promise of tangible outcomes for the camp community. The ‘tangible changes’ they felt in the children in the early stages gave them further incentive to continue.

I was walking and I saw a child with us in Qaderoon hitting his friend, so his friend got angry and hit him back although they are close friends. Then, the child told his friend wait . . . why did you get angry at me, sorry, I didn't mean it, let's stay friends. (Female YM 6)

Not only did the YMs report building a strong relationship with their peers but they became ‘attached to the children’ (10/18) and the children in return got very close to them. The bonds extended to outside the sessions into the community setting. The YMs spoke of the children as little brothers and sisters and greeted each other warmly when they passed each other in the camp.

I got very attached to the children, I got used to them. (Female YM 4)

In addition, the YMs reported that strong bonds of ‘friendship developed’ among themselves and between the YMs and the rest of the team (facilitators, researchers and field coordinator) over time (12/18). This also influenced the YMs to stay with the program. The team members, including the mentors, were described to have become very close to one another and enjoyed working together in a relaxing and healthy environment characterized by mutual respect, understanding and cooperation. YMs reported that they befriended each other and the rest of the team (especially the facilitators) and enjoyed each other's company, gatherings, meetings where they would all mingle. Belonging to a ‘second family’ was mentioned more than once to describe how they felt.

I liked the friendship between us (youth mentors), the trust between us, we used to joke with each other and play with each other like children. Even with the ones older than us, there was mutual trust, we didn't feel that they were at a higher level than us … we didn't feel any distance between us. (Female YM 5)

I didn't feel that I was in a work team, I felt I was in a family or with a group of friends that I have grown up with. For example, when I got sick, they came over or for example if something is wrong with someone, we go to his/her place. And when we go for training in AUB or outside, we feel that we are going out as a family with each other. (Male YM 3)

YMs’ contribution and role: narrowing the gap

All the YMs proudly explained their ‘contribution to the project’ from its inception: they visited homes to explain the project and gain consent of the parents, they conducted the children's assent procedures and they provided input into the sessions and prepared for them ahead of time. They helped in controlling the classes and spent a lot of time with children in the sessions, trips and activities. They described how the YMs’ knowledge of the camp and the parents of the children facilitated the recruitment/consent process because people knew and trusted YMs with their children. Six of the YMs said that parents felt secure that their children are attending this project with the YMs because there are young men and women from the camp and they could entrust their children with them.

Perhaps most importantly, the YMs felt that they acted as a true ‘liaison between the facilitators and the children’ (16/18). YMs reported that they helped facilitators to understand the children better and to deliver the messages/ideas to them more effectively and in a way that children would relate to, identify with and understand. YMs also reported helping the children in expressing themselves/transmitting an idea to the facilitators as they understood the children better. A closer relationship developed between the YMs and the children than with the facilitators. This is expected as the facilitators were in contact with the children for a few hours a week during the sessions, while the YMs were more involved with them in the activities as well as the recreational outings and saw them regularly in the camp. The YM reported that children resorted to them for questions and advice during and after the activities. Given that YMs are closer in age to the children and come from the same camp environment, YMs were more able to identify with the children's feelings and understand their behavior better and they told us they spent more time with them as they saw each other frequently in the camp and in the follow-up visits at home. This was beneficial because they could detect changes in the children more effectively than others in the team. The YMs saw that their role was to narrow the gap between children and facilitators (16/18) and they perceived they had achieved this.

Youth mentors are very close to children because they know them already, neighbors, relatives and so on. At first, children were shy around the facilitators and needed to approach the youth mentors. (Male YM 7)

Youth mentors helped the facilitators in understanding the children. The children considered the youth mentors their friends. (Female YM 10)

Benefits to themselves

All the YMs also saw benefits of the project for themselves in terms of ‘gained skills and personality changes’. The trainings they attended provided them with skills that they applied during the Qaderoon sessions. In addition, the individual sessions provided them with actual experiences and enhanced their ability to interact with children, which they perceived as great benefit to them in the future.

In this kind of work [. . . ] you learn. It's also useful for you in the future, if I want to work as a teacher. It also benefits me in how to deal with children. (Female YM 3)

As a result of participating in all the phases of Qaderoon, YMs reported that they felt they had developed a stronger personality and experienced an increase in self-confidence and courage (11, 18). Consequently, they found it easier to interact and talk with people.

Before [. . . ], I was shy. When I worked in Qaderoon, I noticed that I have grown . . . also my knowledge in life is also good for me. This I discovered in Qaderoon … which increased my self-confidence a lot. The shyness that I used to have when talking with someone educated and has finished university is all gone. (Male YM 2)

Because of this increase in self-confidence, they said they felt they were now able to voice their opinion and express themselves anywhere. YMs started to enjoy socializing more with people of all ages and different backgrounds around them in the camp and built friendships more easily.

‘I am now capable of being in/interacting with any society . . . I have the confidence, it's much easier for me to freely speak my mind, not like before when I was very shy and didn't talk. This thing changed a lot in me … nothing makes me shy in front of people anymore. I'm capable of being myself around them. (Female YM 9)

All the interviews with significant others serve to verify these claims as well.

‘His self confidence got better. He's no longer shy about sitting and discussing things with someone of a higher educational level or older than him. He now makes conversation with older and younger individuals. This thing wasn't in him. (Mother of YM 1)

The YMs also stated that they had become calmer and learned to be more patient. Reasons mentioned for this include the training they have received in preparation for their role, such as anger management techniques; the importance of being role models for children, which requires preparing themselves to do so.

It's not possible to give the children something that we haven't applied on ourselves or it won't work.(Female YM 4)

They believed that Qaderoon has resulted in this significant reduction in their anger. YMs described themselves prior to Qaderoon, as tense or agitated, they would immediately lose their temper, whereas now they confessed they were much calmer (11/18). This change in temperament affected their interaction with family members, friends, as well as children generally.

I became more patient (with children). Before, . . . I was agitated, I wasn't patient, I mean I wanted things to be done quickly. For example, we used to ask the children to draw something and they have 10 minutes only and I would come after 10 minutes and they would still be drawing the picture and haven't colored it yet. Usually, I would become extremely frustrated. Now I don't, I tell them to start coloring. (Male YM 7)

Findings from interviews with family members and friends also corroborate this stated change. Seven of the ten family members and friends acknowledged that YMs became much calmer over time. They reported that they tended to listen and discuss issues, talk calmly, and joke with their parents and siblings, which further improved their relationship. In addition, YMs acquired interaction techniques with children and became more patient with them, which also played a role in strengthening YMs’ relationship with their younger siblings.

Before, he was very agitated. If I wanted to say something, he wouldn't accept it he starts fighting and gets angry and utters offensive words. Now, when I say something, he discusses it with me, even if he's upset. He controls himself. I feel he counts to 10 and sits. I used to avoid him. … Now, I joke and laugh with him … He's much easier to deal with than before. (Mother of YM 2)

She was the type who didn't like children, she didn't have this thing in her but now she's different. She welcomes any child who comes to our house. She sits and plays them or sings to them or jokes. Before, she wasn't like that. (Sister of YM 9)

All 18 of the YMs said they experienced ‘improved interpersonal communication skills’ with children and adults. They could communicate and interact with others in a better way, which led to making more friends.

I analyze everything I hear before I respond to it. I gained this from Qaderoon, in other words most of the talk that used to come out from me was impulsive, that is I used to talk and then think about what I just said. Now, I think and then talk. (Male YM 2)

YMs reported that they now felt capable of negotiating and dealing with different personalities/temperaments of children without using force or fear to control the children's behaviors, a skill that will come in handy when they themselves become parents.

Before for example, if I was walking with my friends and a young child says hello to me, I would tell him to go away. Now, if I'm walking with someone, whoever he/she is, and a little child comes, I hold his hand and tell him to walk with us. (Male YM 5)

Now I have the capability of controlling the children in a friendly manner, that is not controlling them by being authoritarian or condescending … At first even in Qaderoon I used to think that force is required in order to control the children. But on the contrary I found out that if you are able to talk with children and interact with them in a friendly manner, they will respond to you and accomplish things much more productively than by using force. (Female YM 7)

The improved communication skills with family members (parents and siblings) were described as having led to better relationships among them, especially their younger siblings. They took better care of them, communicated (talked calmly), listened and played with them.

At home with my brother even if everyone shouts at him, I talk to him calmly. Now I'm capable of controlling myself because I really felt that one's mental health has an effect so if we all want to shout at him, he will get upset and angry and he will become tense/agitated. So now I know how to interact with him in a better way for his sake. (Female YM 10)

With my sisters, I listen to them more now, that is I don't force my opinion directly on them. Now I listen to them to see what they are thinking. (Male YM 6)

YMs’ family members (mothers or sisters) explained that because of Qaderoon, YMs’ ‘relationship with their families strengthened’ immensely. YMs now enjoyed spending time with them at home, cared about their mothers’ and siblings’ wellbeing, and took their siblings out. They even started to help out with the family expenses including giving their siblings pocket money. They started to sympathize with their parents and felt that they had a responsibility toward the whole family.

Now thank God she loves her siblings. She takes care of them, tutors them, and if they are hungry, she feeds them. She changes their clothes and dresses them. She started taking care of them. Before, she didn't care, she didn't get involved in whatever her siblings were doing. (Mother of YM 6)

The way he helps in the house and his love has changed dramatically. At first if I said my head hurts, he wouldn't care. But now you find him running to get me the blood pressure medication and he argues with me over what I should eat and do, so I really feel that he has become very close to us. Before, he used to stay out late outside, but now he spends time at home. (Mother of YM 2)

Qaderoon also led to ‘improved communication/interaction with friends’.

With my friends, I used to be the leader. Now my friends and I are all at the same level. And my friend is like a brother to me. The way I interact with my friends has changed completely … In Qaderoon, I realized that if my friend loves me I would be OK. I should gain people‘s love and their respect to secure myself for the future. (Male YM 2)

YMs reported that their behavior in public changed because as role models to children, they should behave in the same manner they tell children to.

My behavior in public has changed a lot. For example, I used to joke around with my guy friends on the street in a loud voice or we'd tease each other and stuff like that. Now I stopped doing such things because there are children with us in the project that we know so it's not nice that they see one side of us outside the project and another side in the project . . . (Male YM 1)

YMs reported that they acquired problem-solving skills: they negotiated issues rather than reacted abruptly and were proactive in addressing problems. The project taught them to plan and think thoroughly before taking any decision.

Now I know that I should count till 10 while taking a deep breath when I'm angry … and relax. The way I solve problems has changed. Now I take the problem, analyze it, consider the pros and cons and think how I should act . . . (Male YM 2)

If I want to do something, I look ahead and see what the consequences of that action will be. I always study or calculate my steps that I want to do. Always, I study the thing that I am planning to do. Because of Qaderoon, this strengthened in me. (Male YM 1)

Future aspirations

Qaderoon gave the YMs a chance to ‘experience community work’, which entailed social interaction with different types of people and which they enjoyed. These experiences developed their interest in pursuing related university degrees (public health, psychology and children's issues). A number of YMs (6/18) stated that they would like to continue within this field of work/social work in NGOs working specifically with children.

Other aspirations for the future included continuing as a facilitator when the project is over and transferring the values acquired in Qaderoon to the NGOs in the camp. They were inspired to move on with the project by starting a new phase for other children and suggested ways to involve the children themselves to be YMs in the next phase.

I want the children to become youth mentors, to be placed in the position that we were in. In the next Qaderoon the upcoming year, the children will be 13 yrs old, they can handle responsibility not necessarily a big one i.e. similar to the small projects they did. (Female YM 7)

Discussion and conclusions

Results of this research indicate that the community intervention the YMs were involved in to improve the social skills of younger children in the Palestinian camp was felt to be of multiple benefits to them as well as the children. The project design, the promises it made and the potential benefits to the camp as well as the tangible effects it had on the children and on YMs themselves attracted them and kept them involved. YMs felt they improved their communication skills, and gained self-confidence and self-esteem, a considerable achievement for a socially marginalized and discriminated population.

The findings are congruent with the youth-as-assets literature, which focuses on the resourcefulness of youth [1, 2, 5]. These resources, specifically their understanding of the context and of the children's needs proved valuable for the success of the project. The researchers would recommend the presence and active involvement of youth as mentors in the continued implementation of this project (or any involving children) in this community or the scaling up to others. As mentioned by the YMs, and acknowledged by the research team, their knowledge of the camp and its context facilitated the informed consent and assent process. In addition, their understanding of the camp provided valuable data that led to adjustments in specific activities of the project. The mentors also played an important role as liaisons between the facilitators and children—‘translating’ concepts, feelings and situations.

The findings also confirm the CYD views that involvement of young people is vital to their own development. In their own words, YMs described the changes in their lives and interactions with persons, their improved self-esteem and their changed outlook on the future that came from their involvement in all aspects of the project. This development was confirmed by family members and close friends. The positive benefits they experienced from their membership and their community work with their fellow YMs and researchers impacted their psychological and social well being such as reducing their reaction to stressors and improving their interaction with others of different age groups. Their involvement in the project also offered a new opportunity for them to make decisions on civic affairs, something that the restrictions by the State and the inadequacy of the NGO programs have failed to provide.

Their involvement was also useful for the development of their community—as furthermore suggested by the CYD approach. This is also evident in their changed interactions with children (for example, walking with them whenever they see them on the street), their wish to continue to improve the situation of children in their communities, to work in NGOs applying the skills they learned, and to pursue a university degree that allows them to impact their environment. The YMs in Qaderoon were in fact ‘powerful catalysts’ and engaged partners [3] who continue to work to make their community more positive for children.

The results also corroborate the literature on reasons for and benefits of youth engagement. As suggested in the literature, their personal experience with social injustices led to their engagement to change things for younger children [9]. In addition, they perceived many benefits from participation including feelings of contributing to their community and skills gained [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. The opportunity to influence lives was the greatest attraction to the project. Similar findings from the literature on community coalition development and evaluation suggest that members of coalitions will invest their energy if they perceive that benefits outweigh the costs [28, 29]. As brought out in previous studies, the enhanced sense of community and the social bonds they formed were a key aspect of their continued commitment to the project [9]. The fellowship with other mentors, the facilitators and the rest of the research and field team was a strong motivator of continued involvement and created a norm of attitudes and behavior. This is also described in the coalition literature as the sense of solidarity with other members and increased networking [28].

The results also support the literature on mentoring. The mentors perceived benefits such as increased self confidence as well as enhanced social skills [16]. They reported benefiting from the training, and described the closeness of their bonds with children, all elements of successful mentoring relationships as described in the mentoring literature [17].

The project was implemented in a context of social and economic disadvantage. Youth mentors were paid for their work. Although clearly a benefit for them and their families, none of the mentors mentioned this aspect as a benefit of participation. The mentors were committed to the project for the reasons described above and had intrinsic motivation to participate. It was more than a `job' for them as is evident by their comments.

There are several limitations to this study. The interviews with the YM occurred shortly after the end of the intervention phase of the project and therefore, the results reflect a recency effect. Interviews conducted later may have yielded different expressions of benefits or a more balanced perception of benefits and disadvantages. In addition, although the main interviewer was not linked to the project, she was a recent graduate of the academic institution which coordinated the project. It is possible that responses to the interview questions of both the YMs and their family tended to be more positive and may reflect their wish for the project to continue. It may also be due to the positive interpersonal relationships that developed between the youth mentors and the academic research team. Finally, the results are from work done with youth living under dire social and economic conditions. It is unclear whether these results can be generalizable to other contexts, although their conformity with the previous literature suggests some level of consistency across country and situation.

The findings of this study present a number of implications for community-based projects, which intend to involve youth in community and self-development projects. The authors suggest a model for community capacity building highlighting the above incentives and reasons to stay (Figure 1). The Enabling Attributes Model focuses on three levels of enabling factors: (i) attributes of the community context, (ii) attributes of the community project and (iii) the perceived benefits on the youth themselves and significant others in the community.

The community context includes the community needs and the effects of social injustices on community members that are not addressed by existing social or state structures, but which present a concern for the youth. Also at a community level, community organizations must be ready to partner with the facilitators or researchers. In addition, adults in the community must support youth, value their contribution, and be willing to give of their time for youth development. This box of the model did not directly flow from results but comes from the description of the community (in the background) as well as the authors’ collective understanding from constant contact with the community throughout the project.

The second main level of enabling factors is the project itself. As voiced clearly by the YMs, the project must be appealing or able to show that it responds to the above perceived needs and social injustice and will give the youth an opportunity to be involved meaningfully in the activities as respected partners. The project must have short term as well as longer term benefits to the youth themselves by offering an opportunity to build their capacities through training which enhances autonomy and decision making. The project must also show potential benefits to the groups, the youth identify with and be valuable to significant others, such as parents and researchers.

The perceived benefits from self-reflections and evaluations must be tangible, must provide the youth with space to build/develop their own identities and must be perceived to benefit vulnerable groups around them, such as children.

Young persons will then participate in a community project when they feel: the project is appealing to them and the context is receptive of and has potential to change the status quo. Youth engagement in projects will build their capacity and benefit their community.

The results described herein add to the literature on youth engagement by presenting the experiences of youth in a difficult context in a developing world. However, the consistency of findings between this case and the literature suggests that many motivators of youth engagement are cross-cultural. Youth serving agencies can apply these findings to the development of activities that engage youth for their own gain and in service to their communities.

Funding

University Research Board at the American University of Beirut; Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank reviewers for comments that strengthened the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank the YMs for their boundless energy and hope and their willingness to provide honest and candid insight into their experiences with the Qaderoon project.

The authors would also like to thank the community of BBC for engaging with this Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) project.

References

- 1.Finn JL, Checkoway B. Young people as competent community builders: a challenge to social work. Soc Work. 1998;43:335–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Checkoway B, Richards-Schuster K, Abdullah S, et al. Young people as competent citizens. Press Community Dev J. 2003;38:298–309. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes DM, Curnan SP. Community youth development: a framework for action. Community Youth Dev J. 2000;1 Available at: http://www.cydjournal.org/2000Winter/hughes.html. Accessed: 9 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curnan SP, Hughes DM. Towards shared prosperity, change-making in the CYD movement. Community Youth Dev J. 2002;3:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins DF, Borden L, Villarruel F. Community youth development: a partnership for action. School Community J. 2001;11:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittman K. Balancing the equation: communities supporting youth, youth supporting communities. Community Youth Dev J. 2000;1:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel GD, Ilvento TW. Everybody wins: involving youth in community needs assessment. J Exten. 1995;33 Available at: http://www.joe.org/joe/1995april/a1.php. Accessed: 9 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson-Thompson J, Fawcett SB, Schultz J. A framework for community mobilization to promote healthy youth development. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:S72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harre′ N. Community service or activism as an identity project for youth. J Community Psychol. 2007;35:711–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andolina MW, Jenkins K, Keeter S, et al. Searching for the meaning of youth civic engagement: notes from the field. Appl Dev Sci. 2002;6:189–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton S, Fenzel LM. The impact of volunteer experience on adolescent social development: evidence of program effects. J Adolesc Res. 1988;3:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuire JK, Gamble WC. Community service for youth: the value of psychological engagement over numbers of hours spent. J Adolesc. 2006;29:289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBride AM, Johnson E, Olate R, O′Hara K. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010. Youth Volunteer Service as Positive Youth Development in Latin America and the Caribbean. doi:10.101016/j.childyouth.2010.08.009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stukas AA, Clary GE, Snyder M. Service learning: who benefits and why. Social Policy Report: Society Res Child Develop. 1999;13:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, et al. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30:157–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1014628810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tierny JP, Branch AY. College students as mentors for at-risk youth: A study of six Campus Partners in Learning Programs. Public/Private Ventures; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parra GR, DuBois DL, Helen A, et al. Mentoring relationships for youth: Investigation of a process-oriented model. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:367–388. [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNRWA. Burj Barajneh Profile. Available at: http://www.unrwa.org/etemplate.php?id=134. Accessed: 7 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makhoul J. Unpublished memo CRPH. American University of Beirut; 2003. Physical and Social Contexts of the three Urban Communities of Nabaa, Borj el Barajneh Palestinian Camp and Hay el Sullum. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobsen LB. Summary Report, FAFO report. Norway: Interface Media; 2000. Finding Means: UNRWA's Financial Situation and the Living Conditions of Palestinian Refugees. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarallah YR. Unpublished Master's thesis. Beirut, Lebanon: American University of Beirut, Lebanon; 2005. Adolescents health and well being: the role of ethnicity, built environment and social support. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afifi RA, Makhoul J, El Hajj T, et al. Developing a logic model for youth mental health: participatory research with a refugee community in Beirut. Health Policy Plan 2011. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr001. DOI:10.1093/heapol/czr001. PMID: 21278370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdulrahim S, El Shareef M, Alameddine M, et al. The potential and challenges of an academic-community partnership in a low-trust urban context. J Urban Health. 2010;87:1017–20. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9507-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afifi RA, Nakkash R, El Hajj T, et al. Qaderoon youth mental health promotion programme in the Burj El Barajneh Palestinian refugee camp, Beirut, Lebanon: a community-intervention analysis (abstract) Lancet 2010, July 2 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellehear A. The Unobtrusive Researcher: A Guide to Methods. Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology. 1990;13:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalition for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res. 1993;8:315–30. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortell MS, Zukoski AP, Alexander JA, et al. Evaluating partnerships for community health improvement: tracking the footprints. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2002;27:49–91. doi: 10.1215/03616878-27-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]