Abstract

The rise in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis makes it increasingly important that antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis produce clinically meaningful and technically reproducible results. Unfortunately, this is not always the case because mycobacteriology specialists have not followed generally accepted modern principles for the establishment of susceptibility breakpoints for bacterial and fungal pathogens. These principles specifically call for a definition of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) applicable to organisms without resistance mechanisms (also known as wild-type MIC distributions), to be used in combination with data on clinical outcomes, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. In a series of papers the authors have defined tentative wild-type MIC distributions for M. tuberculosis and hope that other researchers will follow their example and provide confirmatory data. They suggest that some breakpoints are in need of revision because they either (i) bisect the wild-type distribution, which leads to poor reproducibility in antimicrobial susceptibility testing, or (ii) are substantially higher than the MICs of wild-type organisms without supporting clinical evidence, which may result in some strains being falsely reported as susceptible. The authors recommend, in short, that susceptibility breakpoints for antituberculosis agents be systematically reviewed and revised, if necessary, using the same modern tools now accepted for all other bacteria and fungi by the scientific community and by the European Medicines Agency and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. For several agents this would greatly improve the accuracy and reproducibility of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of M. tuberculosis.

Résumé

En raison de l'augmentation de la tuberculose multirésistante, il est de plus en plus important que les tests de sensibilité aux antimicrobiens de la Mycobacterium tuberculosis produisent des résultats cliniquement significatifs et techniquement reproductibles. Malheureusement, ce n'est pas toujours le cas, les spécialistes en mycobactériologie n'appliquant pas les principes modernes généralement acceptés de mise en place de points de rupture de la sensibilité aux pathogènes bactériens et fongiques. Ces principes requièrent plus particulièrement une définition des concentrations minimales inhibitrices (CMI) applicables aux organismes sans mécanismes de résistance (également appelés distributions de CMI de souche sauvage), devant être utilisés en combinaison avec les données sur les résultats cliniques, la pharmacocinétique et la pharmacodynamique. Dans plusieurs publications, les auteurs ont défini les distributions expérimentales de CMI de souche sauvage pour la M. tuberculosis et espèrent que d'autres chercheurs suivront leur exemple et fourniront des données de confirmation. Ils suggèrent que certains points de rupture doivent être révisés, car ils (i) divisent la distribution de souche sauvage, ce qui entraîne une mauvaise reproductibilité des tests de sensibilité aux antimicrobiens, ou (ii) sont sensiblement plus élevés que les CMI des organismes de souche sauvage sans confirmer les preuves cliniques, certaines souches pouvant être à tort reportées comme sensibles. En résumé, les auteurs recommandent que les points de rupture de la sensibilité aux agents antituberculeux soient systématiquement examinés et révisés, en utilisant si nécessaire les mêmes outils modernes qui sont désormais acceptés pour tous les autres bactéries et champignons par la communauté scientifique, l'Agence européenne des médicaments et le Centre européen de prévention et de contrôle des maladies. Pour plusieurs agents, cela améliorerait considérablement la précision et la reproductibilité des tests de sensibilité aux antimicrobiens de la M. tuberculosis.

Resumen

El aumento en la tuberculosis resistente a la medicación hace que resulte cada vez más importante que las pruebas de sensibilidad antimicrobiana de Mycobacterium tuberculosis produzcan resultados clínicamente significativos y técnicamente reproducibles. Desgraciadamente, este no es siempre el caso, porque los especialistas en micobacteriología no han seguido los principios modernos generalizados para establecer los valores límite de la sensibilidad para patógenos bacterianos y micóticos. Estos principios requieren específicamente una definición de las concentraciones inhibitorias mínimas (CIM) aplicables a los organismos sin mecanismos de resistencia (también conocidos como distribuciones de CIM naturales), para usarla en combinación con los datos sobre resultados clínicos, farmacocinéticos y farmacodinámicos. En una serie de artículos, los autores han definido de manera provisional las distribuciones de CIM naturales para M. tuberculosis y esperan que otros investigadores sigan en el futuro su ejemplo y proporcionen datos que lo confirmen. Sugieren que algunos valores límite necesitan una revisión porque o (i) bisecan la distribución natural, lo que provoca una reproducibilidad pobre en las pruebas de sensibilidad antimicrobiana, o (ii) son considerablemente más elevados que los CIM de los organismos naturales sin aportar pruebas clínicas, lo que puede provocar que algunas cepas sean consideradas de manera equivocada como susceptibles. En resumen, los autores recomiendan que se estudien y se revisen sistemáticamente los valores límite de la sensibilidad de los agentes antituberculosos, si fuera necesario, usando las mismas herramientas modernas aceptadas actualmente por la comunidad científica, la Agencia Europea de Medicamentos y el Centro Europeo para la Prevención y Control de Enfermedades para el resto de bacterias y hongos. Según varios agentes, esto mejoraría considerablemente la precisión y reproductibilidad de las pruebas de sensibilidad antimicrobiana de M. tuberculosis.

ملخص

يضفي الارتفاع في السل المقاوم للأدوية المتعددة على نحو متزايد أهمية على اختبار الحساسية لمضادات الميكروبات الخاص بالبكتريا المتفطرة السليّة الذي يسفر عن نتائج ذات دلالة من الناحية السريرية وقابلة للتكرار من الناحية التقنية. ولسوء الحظ، ليس الأمر كذلك دائماً نظراً لعدم اتباع أخصائيي علم البكتريا الفطرية المبادئ الحديثة المقبولة عموماً الخاصة بوضع نقاط حدية للحساسية للممرضات الجرثومية والفطرية. وتطالب هذه المبادئ على نحو محدد بتعريف الحد الأدنى من التركيزات المثبطة ( MIC ) المنطبق على الكائنات العضوية التي لا تملك آليات مقاومة (المعروفة أيضاً بتوزيعات الحد الأدنى من التركيزات المثبطة من النوع البري) على أن يتم استخدامه مقروناً بالبيانات الخاصة بالنتائج السريرية والحرائك الدوائية والديناميكا الدوائية. وحدد المؤلفون في مجموعة من الأوراق توزيعات الحد الأدنى من التركيزات المثبطة من النوع البري المبدئية الخاصة بالبكتريا المتفطرة السليّة ويأملون أن يتّبع الباحثون الآخرون نموذجهم وأن يقدموا بيانات تأكيدية. وهم يشيرون إلى أن بعض النقاط الحدية في حاجة إلى التنقيح نظراً لأنها إما ( 1 ) تنصف التوزيع من النوع البري، مما يؤدي إلى ضعف قابلية تكرار النتائج في اختبار الحساسية لمضادات الميكروبات أو ( 2 ) تكون أعلى بشكل كبير من الحد الأدنى من التركيزات المثبطة للكائنات العضوية من النوع البري بدون تأييد البيّنات السريرية، مما قد يؤدي إلى الإبلاغ على نحو زائف عن بعض الذراري على أنها حساسة وباختصار، يوصي المؤلفون باستعراض منهجي للنقاط الحدية للحساسية الخاصة بالعوامل المضادة للسل وتنقيحها، عند الاقتضاء، باستخدام ذات الأدوات الحديثة المقبولة الآن من قبل المجتمع العلمي ووكالة الأدوية الأوروبية والمركز الأوروبي للوقاية من الأمراض ومكافحتها بخصوص جميع البكتريا والفطريات الأخرى. وهو ما سيحسن بشكل كبير، لعدد من العوامل، دقة اختبار الحساسية لمضادات الميكروبات الخاص بالبكتريا المتفطرة السليّة وقابلية تكرار النتائج التي تم التوصل إليها.

摘要

随着耐多药结核病的增加,结核分枝杆菌药敏试验产生具有临床意义且在技术上可再现的结果越来越重要。遗憾的是,情况并不总是如此,因为结核分枝杆菌专家没有遵守建立细菌和真菌病原体的敏感性折点的公认现代原则。这些原则特别要求定义适用于无耐药机制的有机体的最低抑菌浓度(MIC)(又称野生型的MIC分布),以结合临床疗效、药代动力学和药效学数据使用。在一系列论文中,作者已初步定义结核分枝杆菌的野生型MIC分布,希望其他研究人员效仿此做法,并提供验证数据。论文中提出,一些折点需要修订,因为它们或是(1)平分野生型分布,这将导致药敏试验的再现性很差,或是(2)大大高于野生型有机体的MIC,但没有支持的临床证据,这可能会导致一些菌株被错误地报告为敏感菌株。总之,作者建议,抗结核药物的敏感性折点要接受系统审查和修改,如有必要,使用现在科学界、欧洲药品管理局和欧洲疾病预防和控制中心接受的用于所有其他细菌和真菌的现代工具。对于若干种药物来说,这将极大地改善结核分枝杆菌药敏试验的准确性和可再现性。

Резюме

Рост числа случаев лекарственно-устойчивого туберкулеза увеличивает важность получения клинически значимых и технически воспроизводимых результатов при проверке антимикробной чувствительности Mycobacterium tuberculosis (микобактерий туберкулеза). К сожалению, это не всегда так, поскольку специалисты в области микобактериологии не следовали общепринятым современным принципам установления критических точек восприимчивости для бактериальных и грибковых возбудителей. Эти принципы, в частности, требуют, чтобы определение минимальных подавляющих концентраций (МПК), применимых к организмам без механизмов сопротивления (также известных как распределения МПК для дикого типа), применялось в сочетании с данными о клинических исходах, фармакокинетике и фармакодинамике. В ряде работ авторы определили вероятные распределения МПК для дикого типа M. tuberculosis и выразили надежду, что другие исследователи также последуют их примеру и будут предоставлять подтверждающие данные. Они полагают, что некоторые критические точки нуждаются в пересмотре, поскольку они либо (i) делят распределение дикого типа напополам, что приводит к плохой воспроизводимости проверки антимикробной чувствительности, либо (ii) являются существенно более высокими, чем МПК для организмов дикого типа (без доказательных клинических данных), что может привести к ложной классификации некоторых штаммов как восприимчивых. Резюмируя, авторы рекомендуют при необходимости проводить систематический анализ и пересмотр критических точек чувствительности для противотуберкулезных средств с использованием тех же современных инструментов, которые в настоящее время применяются для всех остальных бактерий и грибков научным сообществом, Европейским агентством по лекарственным средствам и Европейским центром по контролю и профилактике заболеваний. Для нескольких агентов это позволит значительно повысить точность и воспроизводимость проверки антимикробной чувствительности M. tuberculosis.

Introduction

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis makes it necessary to ensure that antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis produce results that are clinically meaningful and technically reproducible. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Among the supranational reference laboratories of the World Health Organization (WHO), the accepted minimum performance level (i.e. the proportion of concordant results) for the testing of susceptibility to streptomycin and ethambutol is only 92%.1 Furthermore, WHO strongly cautions against basing individual treatment for MDR tuberculosis, including ethambutol, pyrazinamide and most second-line drugs, on the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing.2 This situation probably stems from the failure of mycobacteriology specialists to apply the generally accepted criteria for the establishment of susceptibility breakpoints for bacterial pathogens.3,4

For M. tuberculosis, the antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoint (also known as the “critical concentration”) is defined as “the lowest concentration of drug that will inhibit 95% (90% for pyrazinamide) of wild strains of M. tuberculosis that have never been exposed to drugs, while at the same time not inhibiting clinical strains of M. tuberculosis that are considered to be resistant (e.g. from patients who are not responding to therapy)”.2,5 This definition is problematic for two reasons: (i) it automatically categorizes up to 5% of wild-type M. tuberculosis strains as drug-resistant (10% in the case of pyrazinamide); (ii) combination therapy is the standard treatment for tuberculosis and clinical outcome data for individual drugs cannot be readily obtained. Consequently, the critical drug concentrations in current use5,6 are largely based on consensus and lack solid scientific support. In fact, the current definition of “critical concentration” may be what prompted WHO to declare that “…the critical concentration defining resistance is often very close to the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) required to achieve antimycobacterial activity, increasing the probability of misclassification of susceptibility or resistance and leading to poor reproducibility of DST results”.2,6

Modern principles

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints are best determined by breakpoint committees composed of specialists in clinical trial science and in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, population simulation tools, resistance mechanisms, antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods and bacterial population dynamics. Two such committees are the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute of the United States of America. Modern principles for the determination of clinical antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints call for a definition of wild-type MIC distributions (i.e. the Gaussian MIC distributions for organisms of each target species devoid of resistance mechanisms). Strains included within the wild-type MIC distribution are, by definition, devoid of phenotypically detectable acquired or mutational resistance mechanisms, whereas strains outside the wild-type MIC distribution should be suspected of having such resistance mechanisms, although these may or may not be clinically relevant. The highest MIC within the wild-type MIC distribution has been labelled the epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF).3,4 The ECOFF is used, together with clinical, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data, to classify a given wild-type MIC distribution as susceptible (S) (high likelihood of clinical success), intermediate (I) (clinical success uncertain) or resistant (R) (low likelihood of clinical success) under what is known as the SIR system.4 Strains with a MIC above the ECOFF (hence likely to possess resistance mechanisms) are often clinically “R” but could be classified as “I” or “S” if clinically justified. However, this determination is difficult for M. tuberculosis because, since combination therapy is the mandatory treatment for tuberculosis, data on clinical outcomes for individual drugs are difficult to obtain. When this is the case, the clinical breakpoint may have to be based primarily on the clinical outcomes observed for wild-type organisms, and hence on the ECOFF.

Use of wild-type MIC distributions

Wild-type MIC distributions for M. tuberculosis, considered necessary by many experts,7–9 have been largely undetermined. To overcome this gap we recently published tentative wild-type MIC distributions for all major first- and second-line antituberculosis agents. We did so by using a 96-stick replicator and comparing bacterial growth in Middlebrook 7H10 agar containing serial twofold dilutions of drugs with bacterial growth of a control 1:100 dilution in drug-free medium (identical to the routinely used agar proportion method).2,5,10–14 A fully susceptible H37Rv reference strain and a clinical MDR strain were tested in duplicate in each run for all drugs, and intra- and inter-assay MIC variabilities were very good (i.e. less than ± 1 twofold dilutions). MIC distributions can vary depending on the antimicrobial susceptibility testing method used, but preliminary validation data on the same strains in a liquid culture system have shown excellent agreement, both within and between methods (Middlebrook 7H10 versus BACTEC MGIT 960), and a MIC variability of less than ± 1 twofold dilutions,.11,12 Notably, under the current antimicrobial susceptibility testing strategy for M. tuberculosis, the only existing control is the pan-susceptible H37Rv strain, which is normally used only as a control for “S” or “R” classification. No pre-specified MIC ranges exist for the H37Rv strain, although such ranges exist for other bacterial pathogens, and this constitutes another methodological limitation in terms of quality control.

Although most of the tentative ECOFFs were identical or similar to the consensus-based critical concentrations, in this paper we present three unfortunate instances in which they were not. These examples do not involve the most important antituberculosis agents, but they clearly illustrate the usefulness of having defined wild-type MIC distributions and ECOFFs for M. tuberculosis for the setting of antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints.

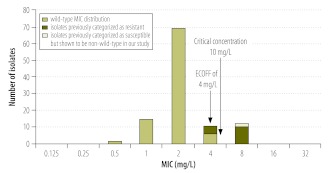

Testing of susceptibility to the first-line drug ethambutol yields poorly reproducible results. This is probably because the current critical concentration splits the upper end of the wild-type distribution (Fig. 1)10 and methodological variation (± 1 twofold MIC dilutions) produces results that oscillate between “S” and “R”.2 This problem could be resolved in part by introducing an “I” category, not routinely used in mycobacteriology at present, and/or by ensuring (as for other bacterial and fungal pathogens) that the clinical antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints do not divide the wild-type MIC distributions.3,10,15

Fig. 1.

Wild-type minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution for ethambutol

ECOFF, epidemiological cut-off.

Note: Sequencing data suggest that approximately 50% of isolates at a MIC of 4 mg/L have genetic resistance mechanisms, whereas none of the isolates at a MIC of 2 mg/L and all of the isolates at a MIC of 8 mg/L have genetically detectable resistance mechanisms. Thus, the current critical concentration of 5 mg/L for Middlebrook 7H10 medium (indicated by an arrow) splits the upper end of the wild-type MIC distribution, which leads to poor reproducibility.

Reproduced with permission from the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

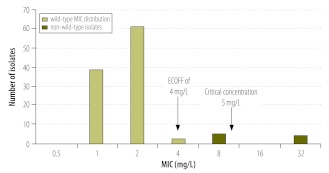

When we defined wild-type MIC distributions for the second-line drug capreomycin, we discovered that the current critical concentration was substantially higher than the epidemiological cut-off (Fig. 2).11 Thus, non-wild type isolates would be classified as “S”. Since there is no evidence that strains with MICs above the ECOFF (i.e. strains likely to harbour resistance mechanisms) can be treated with capreomycin, this serves as an example of a potentially hazardous breakpoint that could lead to ineffective therapy and to the development of further resistance.11

Fig. 2.

Wild-type minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution for capreomycin

ECOFF, epidemiological cut-off.

Note: The non-wild-type isolates had genetic resistance mechanisms and were cross-resistant to the closely related aminoglycosides. Since there is no evidence that infection with non-wild-type strains can be successfully treated, using the recommended critical concentration of 10 mg/L for Middlebrook 7H10 medium (indicated by an arrow) would falsely identify isolates at a MIC of 8 mg/L as susceptible.

Reproduced with permission from the American Society for Microbiology.

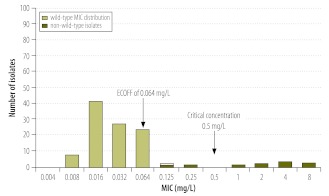

We finally come to the case of rifampicin and its analogue rifabutin. It has long been thought that some rifampicin-resistant strains were susceptible to rifabutin,2 although the clinical evidence is minimal. However, the wild-type MIC distribution shows that the current critical concentration of rifabutin5 is set three twofold MIC dilutions higher than the ECOFF (Fig. 3).13 The scientific grounds for the establishment of this breakpoint remain unclear. Moreover, strains with rifabutin MICs above the ECOFF, which would have been categorized as rifabutin-susceptible but rifampicin-resistant using the current critical concentration, were shown to have rpoB mutations associated with resistance. We therefore believe that previous reports of rifampicin-resistant but rifabutin-susceptible strains resulted primarily or perhaps entirely from a breakpoint artefact.13 To our knowledge, no controlled clinical trial results or pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic data are available to suggest that these strains are treatable with rifabutin.

Fig. 3.

Wild-type minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distribution for rifabutin

ECOFF, epidemiological cut-off.

Note: The non-wild-type isolates were non wild-type for rifampicin and had mutations associated with resistance in the rpoB gene.13 Thus, the present critical concentration of 0.5 mg/L for Middlebrook 7H10 medium (indicated by an arrow) is probably set too high by at least two twofold dilution steps, which has led to the belief, not supported by clinical evidence, that some strains resistant to rifampicin are susceptible to rifabutin.

Reproduced with permission from the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

Discussion

On the whole, our data suggest that the current critical concentrations used to test the susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to antimicrobials should be reviewed and in some cases revised in accordance with modern principles for setting antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints, specifically the use of wild-type MIC distributions and defined ECOFFs, together with any available data on clinical outcomes and on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.3 These methods have been followed to set susceptibility breakpoints for non-fastidious and fastidious organisms, including anaerobic and Helicobacter and Listeria spp., and both Candida and Aspergillus spp. They rest on principles accepted by the European Medicines Agency, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the scientific community at large.

To ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the SIR classification, one must make certain that antimicrobial susceptibility testing breakpoints do not divide the wild-type MIC distributions.3,4,15 This will guarantee that patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis receive effective chemotherapy and will prevent further resistance from developing.

Some may argue that M. tuberculosis strains in different regions could have different wild-type MIC distributions. To our knowledge, this is not supported by any scientific evidence. In fact, data for other bacterial pathogens confirm that wild-type MIC distributions are the same, whether an isolate comes from India or the Arctic or from birds or human beings.16,17

Wild-type MIC distributions for M. tuberculosis should be defined whenever new antituberculosis agents are investigated, as is routinely done for other pathogens. Moreover, the use of wild-type MIC distributions and defined ECOFFs improves the chances of detecting newly acquired resistance. In the case of M. tuberculosis, acquired resistance is expected to be mutational, since the only important mechanism whereby this pathogen acquires resistance is by natural selection of drug-resistant mutants. Hence, if mutations are detected in strains with MICs higher than the ECOFF, these mutations can then be included in the recently recommended molecular kits for the rapid detection of drug resistance.6

In conclusion, we hope to trigger a discussion on susceptibility testing and the setting of susceptibility breakpoints for M. tuberculosis, and we encourage others to support or challenge our MIC distributions for relevant drugs so that mycobacteriology specialists can also access MIC distributions like the ones on the EUCAST MIC-distribution web site, which contains, for instance, 8005 values from 68 investigators for susceptibility of Escherichia coli to meropenem. Our MIC-distributions for M. tuberculosis are now on the MIC web site and we challenge other researchers to contribute theirs. In the meantime, we need to establish a systematic process for review and revision, if needed, of M. tuberculosis susceptibility breakpoints based on the use of the modern tools described in this paper, currently applied by entities such as EUCAST when tasked with setting breakpoints for new antituberculosis agents.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Laszlo A, Rahman M, Espinal M, Raviglione M, WHO/IUATLD Network of Supranational Reference Laboratories Quality assurance programme for drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the WHO/IUATLD supranational reference laboratory network: five rounds of proficiency testing, 1994–1998. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:748–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis – emergency update 2008 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241547581_eng.pdf [accessed 24 April 2012].

- 3.Kahlmeter G, Brown DF, Goldstein FW, MacGowan AP, Mouton JW, Odenholt I, et al. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) technical notes on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:501–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing[Internet]. Definitions of clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cut-off values Växjö: EUCAST; 2012. Available from: http://www.srga.org/Eucastwt/eucastdefinitions.htm [accessed 24 April 2012].

- 5.Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes: Approved Standard M24-A Wayne: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guidelines for surveillance of drug resistance in tuberculosis 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598675_eng.pdf [accessed 24 April 2012].

- 7.Kim SJ. Drug-susceptibility testing in tuberculosis: methods and reliability of results. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:564–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00111304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iseman MD. A clinician’s guide to tuberculosis Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffner SE, Salfinger M. Ad fontes! Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schön T, Juréen P, Giske CG, Chryssanthou E, Sturegård E, Werngren J, et al. Evaluation of wild-type MIC distributions as a tool for determination of clinical breakpoints for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:786–93. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juréen P, Ängeby K, Sturegård E, Chryssanthou E, Giske CG, Werngren J, et al. Wild-type MIC distributions for aminoglycoside and cyclic polypeptide antibiotics used for treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1853–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00240-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ängeby KA, Jureen P, Giske CG, Chryssanthou E, Sturegård E, Nordval lM, et al. Wild-type MIC distributions of four fluoroquinolones active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in relation to current critical concentrations and available pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:946–52. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schön T, Juréen P, Chryssanthou E, Giske CG, Sturegård E, Kahlmeter G, et al. Wild-type distributions of seven oral second line drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:502–9. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werngren J, Sturegård E, Juréen P, Ängeby K, Hoffner S, Schön T, et al. Reevaluation of the critical concentration for drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis against pyrazinamide using wild-type MIC distributions and pncA gene sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1253–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05894-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arendrup MC, Kahlmeter G, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Donnelly JP. Breakpoints for susceptibility testing should not divide wild-type distributions of important target species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1628–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01624-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson C, Kanungo R, Kahlmeter G, Rao SR, Krantz I, Norrby SR, et al. High frequency of multiresistant respiratory tract pathogens at community level in South India. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:740–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00707.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sjölund M, Bengtsson S, Bonnedahl J, Hernandez J, Olsen B, Kahlmeter G. Antimicrobial susceptibility in Escherichia coli of human and avian origin–a comparison of wild-type distributions. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:461–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]