Increasing size of G3BP-induced stress granules is associated with a threshold or switch that must be triggered for eIF2α phosphorylation and subsequent translational repression to occur. Stress granules are active in signaling to the translational machinery and may be important regulators of the innate immune response.

Abstract

Stress granules are large messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) aggregates composed of translation initiation factors and mRNAs that appear when the cell encounters various stressors. Current dogma indicates that stress granules function as inert storage depots for translationally silenced mRNPs until the cell signals for renewed translation and stress granule disassembly. We used RasGAP SH3-binding protein (G3BP) overexpression to induce stress granules and study their assembly process and signaling to the translation apparatus. We found that assembly of large G3BP-induced stress granules, but not small granules, precedes phosphorylation of eIF2α. Using mouse embryonic fibroblasts depleted for individual eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) kinases, we identified protein kinase R as the principal kinase that mediates eIF2α phosphorylation by large G3BP-induced granules. These data indicate that increasing stress granule size is associated with a threshold or switch that must be triggered in order for eIF2α phosphorylation and subsequent translational repression to occur. Furthermore, these data suggest that stress granules are active in signaling to the translational machinery and may be important regulators of the innate immune response.

INTRODUCTION

In living cells messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) complexes dynamically shuttle between actively translating polysomes and translationally silenced compartments, where they accumulate in stress granules and processing bodies, the latter being where RNA decay may occur (Rzeczkowski et al., 2011). Stress granules (SGs) are large mRNP aggregates that contain stalled translation initiation complexes and are formed when the cell encounters several types of stress. The stalled translation initiation complexes that concentrate in stress granules include many translation initiation factors (eukaryotic initiation factors [eIFs]), polyadenylated mRNAs, the 40S ribosomal subunit, and RNA-binding proteins, whereas the 60S ribosomal subunit is excluded (Anderson and Kedersha, 2002; Kedersha et al., 2002). Inhibition of translation at the initiation phase before ribosome subunit joining is well documented to drive the formation of stress granules. This observation is supported by translational inhibition with pateamine A, 4GE1, and edeine, which all induce SG formation, whereas knockdown of some eIFs, inhibition of ribosomal subunit joining, and even inhibition of the elongation phase of protein synthesis do not cause SG assembly (Thomas et al., 2005; Dang et al., 2006; Mokas et al., 2009). Of interest, overexpression of several RNA-binding proteins, including Tia1, CPEB1, cold-inducible RNA-binding protein, and RasGAP SH3-binding protein (G3BP), all induce SG formation (Tourriere et al., 2003; Gilks et al., 2004; Wilczynska et al., 2005; De Leeuw et al., 2007).

The heterotrimeric eIF2 (α, β, and γ subunits) functions in a ternary complex containing initiator methionyl-tRNA and GTP. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is responsible for delivery of initiator methionyl-tRNA to the ribosome in a GTP-dependent manner. Release of eIF2 from the translation initiation complex requires GTP hydrolysis, and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B is responsible for recycling of GDP for GTP in eIF2 before subsequent rounds of translation initiation (Merrick, 2004). Many stresses that induce SG assembly cause translational repression by stimulating kinases that phosphorylate serine 51 of eIF2α (Kedersha et al., 1999; McEwen et al., 2005). This event blocks the nucleotide exchange cycle by causing stable association of eIF2 and eIF2B, thereby sequestering the limiting eIF2B (Dever et al., 1995). Disruption of the eIF2 nucleotide exchange cycle prevents delivery of initiator methionyl-tRNA to the ribosome, causing accumulation of initiation complexes lacking the ternary complex. There are four well-known eIF2α kinases that can respond to various stresses and repress translation: protein kinase R (PKR), which senses double-stranded RNA; protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), which senses endoplasmic reticulum stress; heme-regulated inhibitor kinase (HRI), which senses oxidative stress and heme deficiency; and general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), which senses nutrient availability.

During the course of our studies, we found that G3BP overexpression induces stress granules in a dose-dependent manner. Using microscopic techniques, we analyzed individual cells and discovered that translational repression and eIF2α phosphorylation did not generally appear until large G3BP-induced stress granules were formed. Furthermore, we found that PKR was responsible for the induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by G3BP-induced stress granules. These data change the view of stress granules as inert depots for translationally silenced mRNPs to structures that may promote cellular signaling to the translational machinery for translational repression.

RESULTS

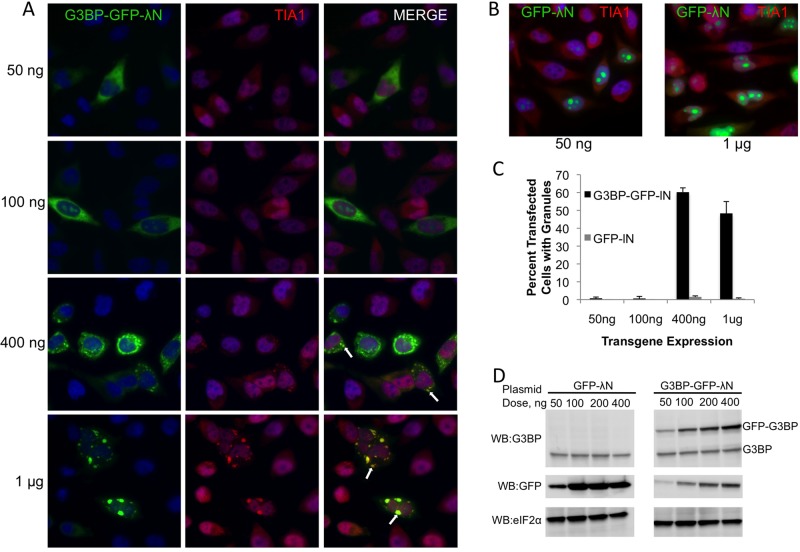

G3BP overexpression induces stress granules in a dose-dependent manner

Several proteins, including G3BP, have been shown to induce stress granule formation during conditions of overexpression (Tourriere et al., 2003; Gilks et al., 2004; Hua and Zhou, 2004; Kedersha et al., 2005). During our overexpression studies of G3BP we noted that many cells contained no stress granules despite significant G3BP expression, some cells contained small G3BP-induced stress granules, and others contained large G3BP granules. To understand the underlying causes for the differences in stress granule appearance and size, we titrated G3BP-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-λN expression plasmid into HeLa cells to investigate whether G3BP-induced granules are concentration dependent. We found that higher concentrations of G3BP could generally induce larger stress granules, as indicated by colocalization with another stress granule marker protein, Tia1 (Figure 1A, white arrows). This observation is due to the cellular function of G3BP and not a result of high concentrations of nucleic acids from the transfection procedure, because equivalent amounts of GFP-λN expression plasmid did not induce Tia1-positive stress granules (Figure 1B). Quantification of stress granules in transfected cells as a function of plasmid concentration demonstrates the specificity of this effect. At 400 ng of transfected plasmid, G3BP was ∼30-fold more potent at inducing stress granules as compared with the GFP-alone control (Figure 1C). Of interest, at the highest doses, many cells expressing G3BP do not contain granules, indicating that some cells are resistant to G3BP-induced granule formation (Figure 1C). Analysis of levels of G3BP-GFP-λN by Western blotting followed by densitometric analysis indicates that approximately a threefold increase in G3BP over endogenous levels is sufficient to trigger stress granule formation (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1:

G3BP granules are induced in a dose-dependent manner in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of either G3BP-GFP-λN (A) or GFP-λN (B) plasmid and stained for Tia1 as indicated in Materials and Methods. (C) Between 125 and 150 transfected cells were manually counted and scored for Tia1-positive stress granules and are presented as percentage transfected cells with stress granules. Error bars represent SD from three independent counts. (D) Immunoblots showing levels of GFP-G3BP-λN or GFP-λN transgene relative to endogenous G3BP and eIF2α levels.

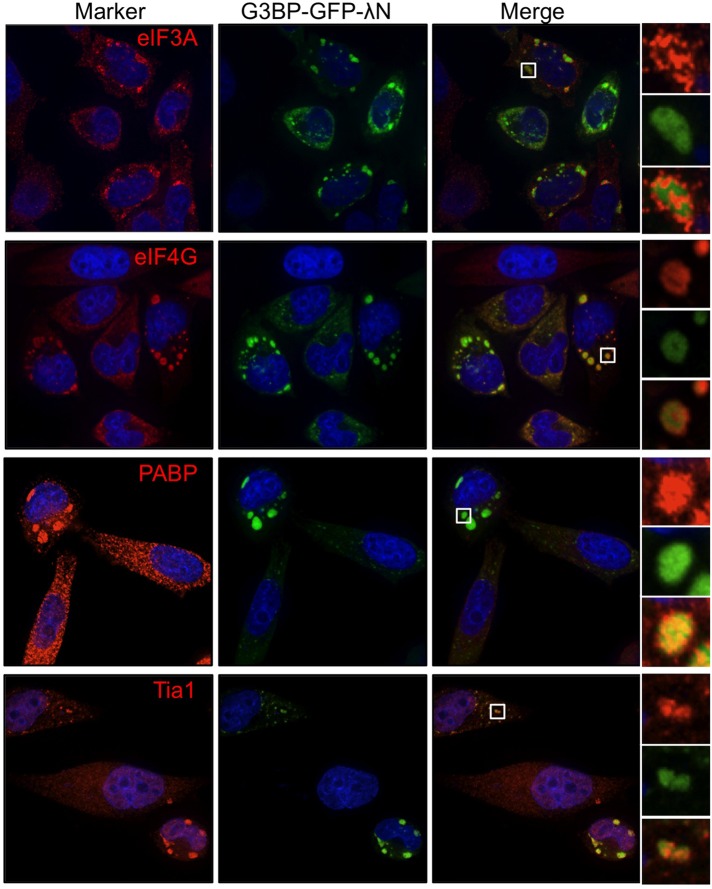

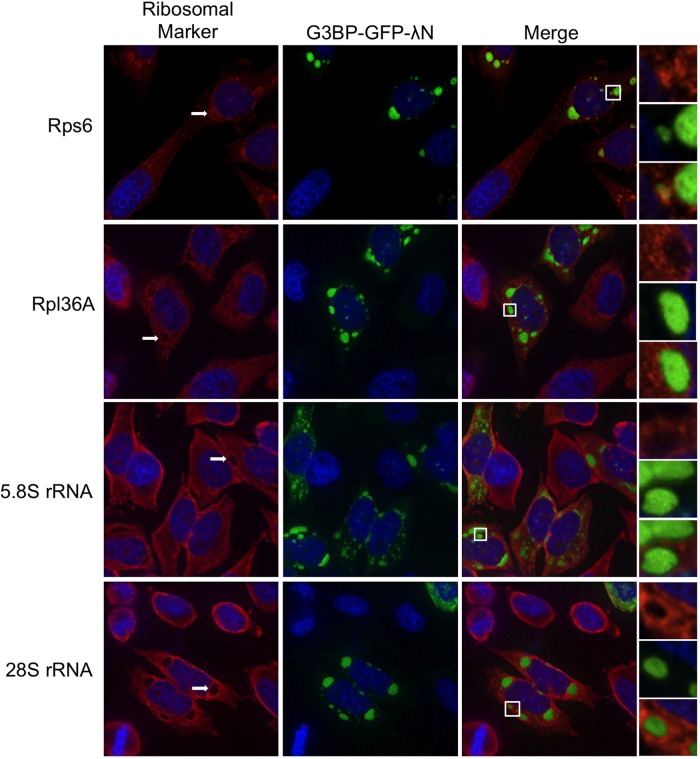

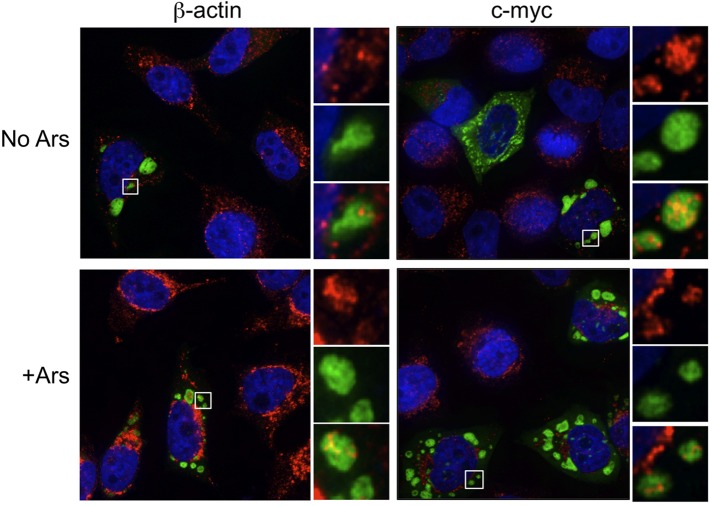

By definition stress granules contain stalled translation initiation complexes comprising several translation initiation factors, mRNA, and the small, but not large, ribosome subunit. Because recent data suggest that the composition of stress granules may differ in a stress-dependent manner (Piotrowska et al., 2010; Buchan et al., 2011), we performed a comprehensive analysis of the components of G3BP-induced granules. Previous data indicated that eIF4G, poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), and eIF3b are all recruited to G3BP-induced stress granules (Kedersha et al., 2005). We confirmed localization of eIF4G and PABP, whereas eIF3b and Tia1 both colocalized with G3BP-induced SGs in HeLa cells as predicted (Figure 2). We were also able to detect the small ribosomal subunit marked by ribosome protein S6 (rps6) in G3BP-induced granules, as expected (Kedersha et al., 2002). The large ribosomal subunit was not efficiently recruited to G3BP-induced stress granules, as indicated by immunostaining for the 28S protein rpl36A (Figure 3). Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis demonstrated that 5.8S rRNA, which strongly interacts with the 60S ribosomal subunit, and the 28S rRNA component of the large ribosome subunit were also excluded from G3BP-induced granules (Figure 3, white arrows). Finally, the c-myc and β-actin mRNAs also localized to G3BP-induced granules (Figure 4). The specificity of these antibodies and RNA probes can be validated by consistent, diffuse staining in untransfected cells in the same fields as those with G3BP-induced SGs (Figures 2–4). These results extend previous data by other groups to show inclusion of additional markers of canonical stress granules in G3BP-induced granules (Kedersha et al., 2002; Tourriere et al., 2003). From these data we conclude that G3BP-induced granules resemble canonical stress granules by all of the functional markers examined.

FIGURE 2:

G3BP-induced stress granules colocalize with initiation factors and RNA-binding proteins. HeLa cells were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN and stained for the indicated markers of stress granules as detailed in Materials and Methods. Cells were imaged with deconvolution microscopy.

FIGURE 3:

G3BP-induced stress granules differentially stain for 40 and 60S ribosome markers. HeLa cells were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN and stained for either the 40S (rps6) or the 60S (rpl36A) ribosomal subunits. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was conducted with probes directed against 5.8S and 28S rRNA as indicated in Materials and Methods. After staining, cells were imaged using deconvolution microscopy.

FIGURE 4:

G3BP-induced stress granules colocalize with mRNAs. HeLa cells were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN, and c-myc or β-actin mRNAs were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization as indicated. Transfected cells were either left untreated (no Ars) or treated with 200 μM arsenite (+Ars) 30 min before fixation and processing. Cells were imaged using deconvolution microscopy.

G3BP overexpression induces eIF2α phosphorylation and translational inhibition

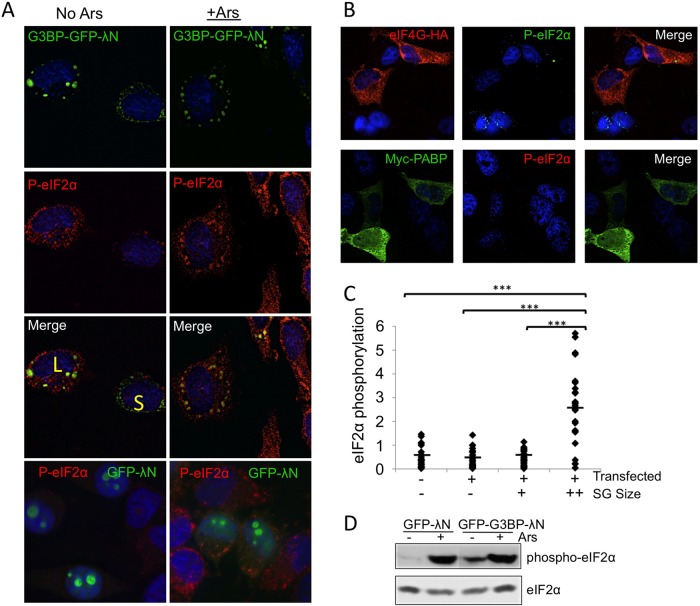

Because G3BP-induced SGs resemble canonical stress granules and phosphorylation of eIF2α is known to induce SG formation (Kedersha et al., 1999, 2000, 2002), we investigated whether cells containing G3BP-induced granules exhibit eIF2α phosphorylation by deconvolution microscopy. Cells with large G3BP-induced stress granules stained strongly for phosphorylated eIF2α (Figure 5A, cell marked with L). Furthermore, phosphorylation levels were similar to those in arsenite-treated controls, in which translational inhibition is well characterized (Figure 5A; McEwen et al., 2005; White et al., 2011). Live-cell imaging revealed that large G3BP-induced SGs did not undergo significant changes in size or shape upon arsenite treatment (unpublished data). To investigate whether other RNA-binding proteins and components of SGs could also induce eIF2α phosphorylation, we examined cells expressing PABP and eIF4G. In both cases, significant eIF2α phosphorylation was not present in overexpressing cells (Figure 5B). These data support results from GFP-λN expression indicating that transfection alone is not sufficient to induce SG assembly and support the specificity of G3BP in induction of SGs and eIF2α phosphorylation.

FIGURE 5:

Large G3BP-induced stress granules induce eIF2α phosphorylation. HeLa cells were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN (A, C), GFP-λN (A), or PABP or eIF4G (B) and stained with antibodies that detect eIF2α phosphorylation before deconvolution imaging. Arsenite stress was applied as described in Materials and Methods. Cells with large or small granules are indicated with a yellow L or S, respectively. Color channels are switched for eIF4G staining because of antibody availability. (C) Intensities of eIF2α phosphorylation in G3BP-expressing HeLa cells were quantified with Pipeline Pilot analysis tools, and a Student's t test was conducted. Untransfected and transfected cells (− or +) and stress granule size groups (−, no granules; +, small granules; ++, large granules) are indicated. The y-axis represents (phosphorylated eIF2α intensity [arbitrary units]/cell area × 1000). ***p ≤ 0.001. The minimum threshold size for large granules was ∼1.4 μM2. (D) Immunoblots for eIF2α or phosphorylated eIF2α in cells expressing indicated transgenes. Cells were also treated with arsenite as indicated.

Because we observed different sizes of granules in cells overexpressing G3BP, we investigated whether granule size had any correlation with eIF2α phosphorylation by quantifying the intensity of eIF2α phosphorylation at the single-cell level. Strikingly, we found that levels of eIF2α phosphorylation were low or not apparent in many cells with smaller G3BP-induced SGs, similar to transfected cells lacking granules and untransfected cells (Figure 5, A, cell marked S, and C). Robust phosphorylation was not observed until stress granules reached a certain size, suggesting that a cellular switch or threshold regulates eIF2α phosphorylation. During arsenite stress, eIF2α phosphorylation precedes assembly of even small granules, suggesting that this mechanism is dependent on the stress signaling and SG assembly (unpublished data). Immunoblot analysis of G3BP-transfected cells indicated that increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation were evident at the population level compared with cells expressing GFP, though eIF2α phosphorylation was not as high as for cells treated with arsenite (Figure 5D). This was consistent with our finding that only a maximum of 60% of cells expressing GFP-G3BP-λN form granules (Figure 1C).

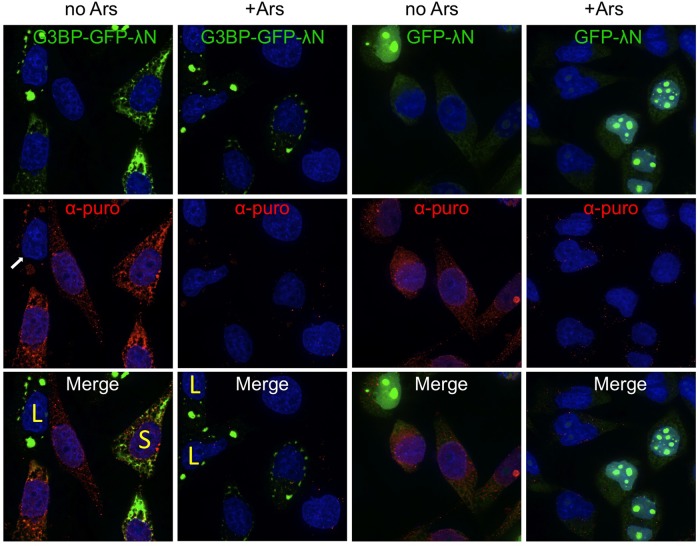

Although eIF2α phosphorylation is generally associated with repressed translation, we sought to confirm that levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in cells with large G3BP-induced SGs correlate with translational repression in individual HeLa cells. Therefore we monitored translation using a short pulse of puromycin, which can be incorporated into nascent polypeptides and detected by immunofluorescence with an antibody directed against puromycin (ribopuromycilation assay [RPA]; Schmidt et al., 2009; David et al., 2011). We found that cells containing large G3BP-induced SGs pronounced strident translational repression, whereas those with smaller granules had ongoing translation similar to cells lacking granules or those that were untransfected (Figure 6). Levels of translation in cells with large G3BP-induced SGs (Figure 6, cells marked with L) were very low or undetectable with the RPA assay, similar to levels observed in arsenite-treated controls. These data are consistent with our observation that induction of eIF2α phosphorylation occurred primarily in cells containing large G3BP-induced SGs (Figure 5, A and C). Translational repression was not observed in cells overexpressing GFP-λN, suggesting that transfection alone is insufficient to induce translational repression. These results were also confirmed with another method to detect active translation, known as bio-orthogonal noncanonical amino acid tagging (Supplemental Figure S1; Dieterich et al., 2007). Furthermore, we performed fluorescence recovery after whole-cell photobleaching on cells expressing both G3BP-GFP-λN and mCherry. Whole-cell photobleaching was performed to block fluorescence restoration by transport of unbleached mCherry from elsewhere in the cytoplasm, forcing assay reliance on de novo translation of mCherry. Those data indicated that only cells with large stress granules were unable to translate more mCherry after photobleaching (Supplemental Figure S2). Of interest, in RPA analysis of cells containing large G3BP-induced granules, we consistently detected SG-associated puromycin staining, indicating the presence of a distinct subset of ribosomes/mRNPs in SGs that possibly retain unreleased nascent peptides or preferential inclusion of nascent peptides into SGs (Figure 6). It will be interesting to identify the nature of these ribosomes/mRNPs in future studies.

FIGURE 6:

RPA analysis of cells containing G3BP-induced stress granules. G3BP-GFP-λN or GFP-λN plasmids were transfected into HeLa cells, and RPA analysis was conducted as indicated in Materials and Methods. Translation is represented by α-puro. For each transfected plasmid, cells were either treated without (no Ars) or with (+Ars) to control for antibody specificity. Cells with large or small granules are indicated with a yellow L or S, respectively. Cells were imaged with a deconvolution microscope.

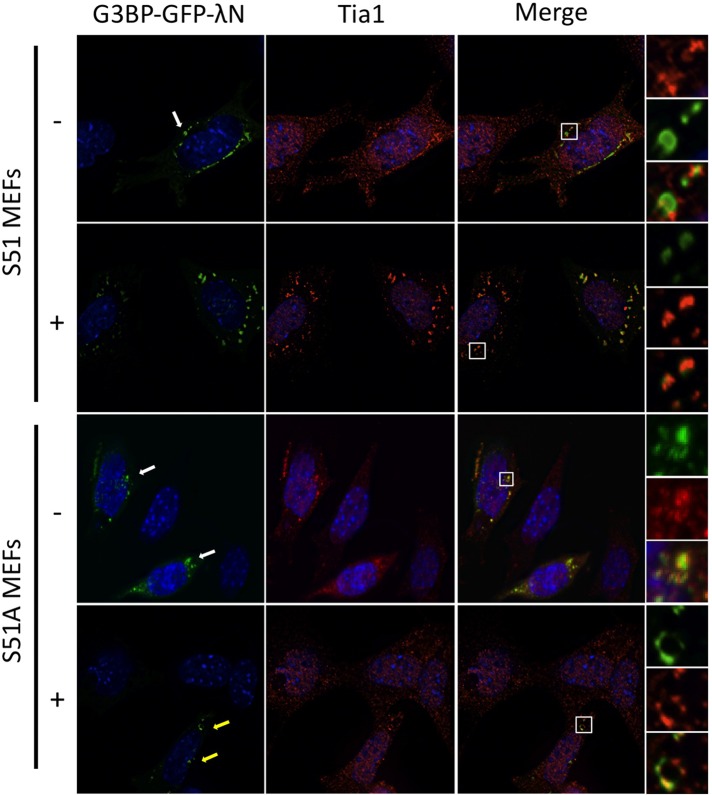

G3BP stress granules can be induced in mouse embryonic fibroblasts containing mutant eIF2α

Our data indicate that for at least G3BP-induced granules, eIF2α phosphorylation and translational repression could precede assembly of large stress granules. Therefore we reasoned that G3BP-induced SGs could be observed in cells without translational repression. To test this hypothesis, we expressed G3BP-GFP-λN in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) expressing either serine 51 wild-type (S51) or a serine 51-to-alanine (S51A) nonphosphorylatable mutant of eIF2α. We confirmed that phosphorylation of eIF2α is indeed blocked in response to arsenite with the mutant MEFs by Western blotting (see Figure 9C later in the paper). With this system we were able to induce SGs containing Tia1 and G3BP in both S51 and the nonphosphorylatable S51A mutant MEFs without arsenite stress (Figure 7, white arrows). This demonstrates that G3BP can induce SG formation independently of eIF2α phosphorylation. Arsenite induces translation shutoff and SG formation by activation of the eIF2α kinase HRI (McEwen et al., 2005). Thus, as expected, arsenite-induced granules were readily observed in the wild-type S51 MEFs but were absent in mutant S51A MEFs (Figure 7). In this case, only cells with G3BP-GFP-λN expression contained stress granules (Figure 7, yellow arrows). Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis indicated that SGs in S51A MEFs also contained eIF3a and eIF4G, similar to the G3BP-induced granules observed in HeLa cells (unpublished data).

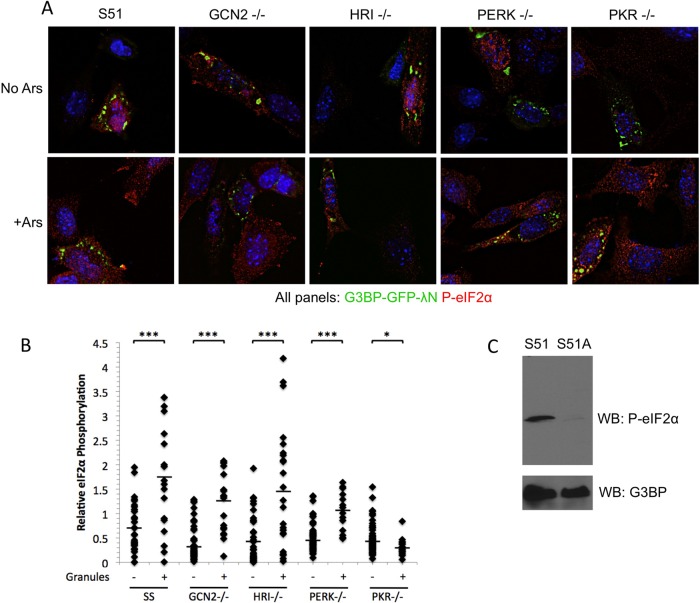

FIGURE 9:

PKR mediates eIF2α phosphorylation by G3BP-induced stress granules. (A) Mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing wild-type eIF2α (S51) or deleted for eIF2α kinases (−/−) were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN and either left untreated (no Ars) or treated (+Ars) for 30 min with 200 μM arsenite. Subsequently, cells were fixed and stained for phosphorylated eIF2α (red) and imaged with deconvolution microscopy. (B) Cells in >25 fields for each genotype and each condition were imaged and quantified for eIF2α phosphorylation. Cells were classified based on the absence (−) or presence (+) of granules, and the two groups for each genotype were statistically compared using an equivariant, two-tailed Student's t test. ***p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05. (C) Immunoblot of S51 and S51A MEFs treated with 200 μM arsenite for 30 min, showing phosphorylated eIF2α and endogenous G3BP as a loading control.

FIGURE 7:

eIF2α mutant S51A MEFs are capable of forming G3BP-induced stress granules. Both S51 and S51A eIF2α mutant MEFs were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN. Transfected S51 and S51A MEFs were either left untreated (−) or treated for 30 min with 200 μM arsenite (+) followed by fixation and staining for Tia1 before deconvolution imaging.

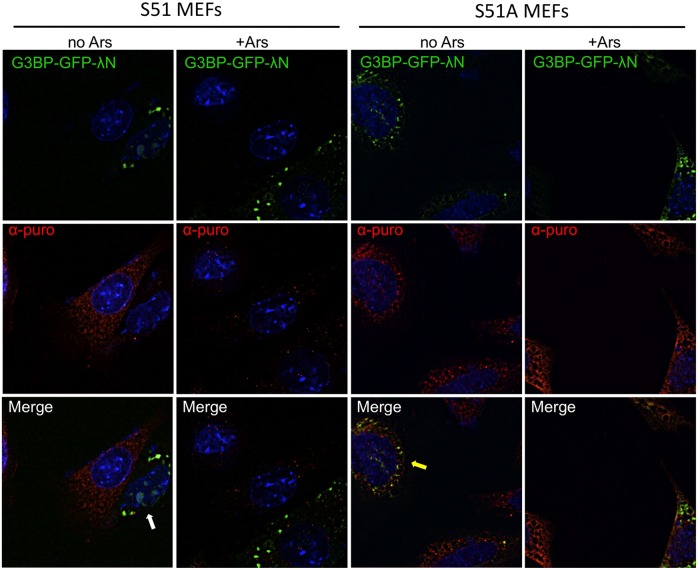

To determine whether the G3BP-induced granules present in S51A MEFs were capable of translational repression through another pathway independent of eIF2α phosphorylation, we used RPA to measure translation in both the wild-type eIF2α S51 and mutant S51A MEFs. This analysis indicated that translation was blocked in S51A MEFs containing G3BP-induced granules as expected (Figure 8, white arrow) but, surprisingly, proceeded at normal levels in the S51A MEFs despite the presence of G3BP-induced SGs (Figure 8, yellow arrow). In fact, levels of translation were comparable to those for untransfected controls in the same fields as cells with G3BP-induced SGs. These data indicate that, indeed, in this case G3BP-induced SG assembly precedes translational repression since we can eliminate the later step of translational repression without significantly affecting assembly of these granules.

FIGURE 8:

RPA analysis of eIF2α mutant S51A MEFs indicates S51A MEFs are translating despite the presence of G3BP-induced stress granules. Puromycin stain indicates nascent polypeptide synthesis. S51 and S51A MEFs, as indicated, were transfected with G3BP-GFP- λN and either left untreated (no Ars) or treated (+Ars) for 30 min with 200 μM arsenite before fixation and staining for translating ribosomes (α-puro). Cells were imaged by deconvolution microscopy.

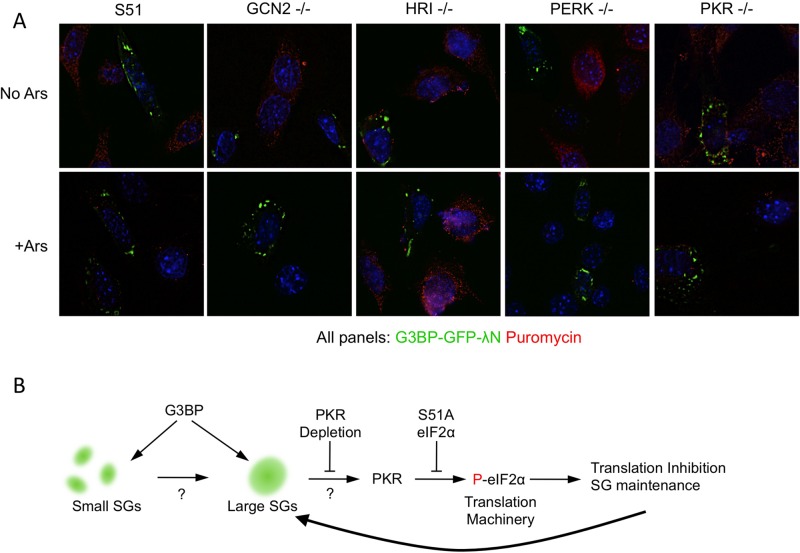

PKR mediates induction of eIF2α phosphorylation by G3BP-induced SGs

In an effort to elucidate which eIF2α kinase mediates translational repression by G3BP-induced SGs, we used a panel of kinase-knockout MEFs. Using these MEFs, we could identify which kinase was capable of supporting G3BP-induced SG assembly without eIF2α phosphorylation at the single-cell level with fluorescence microscopy. As expected, we were able to induce eIF2α phosphorylation in wild-type MEFs in a dose-dependent manner as observed earlier in HeLa cells (unpublished data). Every MEF genotype was capable of forming G3BP-induced SGs in response to high concentrations of G3BP expression plasmid. Of interest, however, the only genotype lacking significant consequent eIF2α phosphorylation when SGs formed was the PKR-knockout cells (Figure 9A). Levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in PKR-knockout cells with granules resembled those observed in untransfected cells, indicating that PKR is the principal kinase that mediates eIF2α phosphorylation after G3BP-induced SGs assemble. Quantification of eIF2α phosphorylation in cells with G3BP-induced SGs indicated that the fold change in cells without G3BP-induced SGs versus cells with SGs was significant between all the other MEF genotypes. This suggests that minimal cross-talk occurs between eIF2α kinases in response to G3BP-induced SGs (Figure 9B). A possible minor role for PERK cannot be excluded since phosphorylation levels did not increase as robustly in response to G3BP-induced stress granule formation. The increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation were statistically significant for all cell types examined, with the exception of PKR-knockout MEFs, in which G3BP SG-containing cells had lower levels of eIF2α phosphorylation than those cells without granules. These data suggest that PKR is the most prominent kinase in the signaling events responsible for translational repression after assembly of G3BP-induced granules. We were unable to distinguish between small and large granules in MEFs because MEF SGs are reproducibly smaller, and therefore only groups with and without G3BP-induced granules are represented (Figure 9B). We repeatedly observed cell line–specific variation in stress granule size, and so the inability to distinguish between small and large granules was not surprising (unpublished data). Because quantification of eIF2α phosphorylation in MEFs is dependent on the specificity of the antibody, we performed a Western blot with S51 and S51A MEFs during arsenite treatment and confirmed that the antibody is specific (Figure 9C). Under these conditions, eIF2α phosphorylation is strongly induced in only the S51 MEFs, whereas no signal was observed in S51A mutant MEFs.

To confirm that PKR is responsible for eIF2α phosphorylation and subsequent translational repression, we conducted RPAs for translation activity on each MEF genotype. As expected from the eIF2α phosphorylation data, only the PKR-knockout cells lacked translational repression characteristic of G3BP-induced granules (Figure 10A). PKR-knockout cells translated at levels equivalent to nontransfected controls within the same fields. Here again, the specificity of the assay is indicated by the lack of puromycin/translation signal in arsenite-treated controls, where translation is abrogated. The results with PKR-knockout cells resemble those observed with eIF2α S51A mutant MEFs, in which G3BP-induced SGs were present without eIF2α phosphorylation and with retention of ongoing translation. These results provide further credence to the idea that G3BP-induced SGs assemble before eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 10A).

FIGURE 10:

Translation persists in PKR-knockout MEFs despite the presence of G3BP-induced stress granules. (A) Cells were transfected with G3BP-GFP-λN and either left untreated (no Ars) or treated (+Ars) with arsenite as described in Materials and Methods. RPA was then performed to detect translating ribosomes (α-puromycin; red). (B) Schematic illustration of G3BP-induced granule formation and subsequent eIF2α phosphorylation by PKR. G3BP induction of both small and large SGs is illustrated with arrows toward both sizes of granules. Points of the pathway that have not been further elucidated are depicted with question marks.

DISCUSSION

Previous data in the field of mRNP granule biology established that stress granules are dynamic storage facilities for mRNAs and translation factors. In this view SGs are positioned downstream of many stress detection signals that first restrict translation (Kwon et al., 2007; Ohn et al., 2008; Leung et al., 2011), causing accumulation of stalled translation initiation complexes, which are then assembled into stress granules via microtubule-dependent molecular motors (Ivanov et al., 2003; Kwon et al., 2007). This positions SGs as a consequence of stress signaling; however, the reverse role of SGs functionally signaling out to the translation apparatus to maintain a state of translational repression had not previously been established. Although the idea of SGs preceding eIF2α phosphorylation had not been previously documented, the conceptual distinction between large and small granules had been made for both arsenite and azide stressors (Buchan et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). In the case of arsenite stress in which samples were examined every 5 min after arsenite application, we did not see appearance of eIF2α phosphorylation before assembly of granules (unpublished data). On the contrary, eIF2α phosphorylation is prominent before even small granules are assembled.

Our data indicate that G3BP-induced SGs can signal to the translation apparatus by stimulating eIF2α phosphorylation in a PKR-dependent manner (Figure 10B). This model explains how granule formation can be observed in both the PKR-knockout and S51A mutant MEFs that do not have induced eIF2α phosphorylation. Although we only have evidence that phosphorylated eIF2α is present at the same time as large SGs, we predict PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation as a consequence of large SG assembly because eIF2α phosphorylation is not observed with small SGs (Figure 10B). We hypothesize that the PKR activation and eIF2α phosphorylation may be involved in maintenance of SGs during other stresses after an initial phase of eIF2α phosphorylation by other kinases (e.g., HRI activation during arsenite stress).

Some points are not resolved within this model for induction of eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 10B). For example, it is not known what is being sensed in the cell that triggers the coalescence of small granules into large granules. We conjecture that the depletion of initiation factors or RNA-binding proteins into small granules is sensed because it is unlikely that substantial protein synthesis can occur in the absence of accessible translation initiation factors. Sensing of small granules may also depend on localization of sufficient carrier proteins that allows high-affinity interaction between the small granule and molecular motors (Loschi et al., 2009). This would then permit coalescence of the small granule and initiation of subsequent signaling. Another point that is unresolved is how PKR is activated after large-granule assembly. We hypothesize that compaction of RNA in a granule that is sensed by PKR could result in eIF2α phosphorylation. Alternatively, derepression of PACT/Rax may occur, which is the only cellular activator of PKR, which in turn may phosphorylate PKR in the absence of double-stranded RNA (Patel and Sen, 1998; Ito et al., 1999; Garcia et al., 2006). Finally, stress granules could activate a signaling molecule upstream of PKR by such as MyD88 or IRAK1 (i.e., toll-like receptor 3, 4, or 9 signaling; Garcia et al., 2006).

Our finding that PKR is responsible for eIF2α phosphorylation is supported by earlier stress granule work in which Tia1 was overexpressed (Kedersha et al., 1999). Kedersha and colleagues showed that expression of either the nonphosphorylatable S51A mutant of eIF2α or the adenoviral VAI gene, which inhibits PKR activity, was sufficient to reduce induction of SGs by Tia1 overexpression. However, they concluded that overexpression of transgenes introduces so much exogenous RNA that PKR is activated and eIF2α is phosphorylated, resulting in SGs (Kedersha et al., 1999). Our data provide new insight that forces us to reexamine these conclusions. Specifically, expression of G3BP in MEFs expressing the nonphosphorylatable S51A mutant as the sole source of eIF2α still induced stress granules. Furthermore, expression of GFP-λN, PABP, and eIF4G do not induce stress granules despite similar expression from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) transcription promoter.

The observation that with high transgene expression eIF2α phosphorylation was only observed with large granules also argues against activation of PKR by exogenous RNA. Finally, we tested many deletion mutants of G3BP that do not induce eIF2α phosphorylation when expressed from a CMV promoter, indicating that a specific sequence in the exogenous RNA is not responsible for PKR activation and resulting SGs (unpublished data).

Based on the prominent role of SGs and PKR in antiviral innate immunity, the finding that PKR mediates eIF2α phosphorylation coinciding with large G3BP-induced SG assembly makes sense. Many viruses target SGs for disassembly and encode proteins that are known inhibitors of PKR activity (Garcia et al., 2006; White and Lloyd, 2012). Of interest, PKR participates in several toll-like receptor signaling pathways, including toll-like receptors 3, 4, and 9 (Horng et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2003). PKR activity also regulates NF-κB transcriptional activity (Kumar et al., 1997; Gil et al., 2001) and can induce c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity (Goh et al., 2000; Taghavi and Samuel, 2012). Therefore it is reasonable that these proteins may be activated by assembly of large G3BP-induced granules.

JNK signaling has recently become a focal point in mRNP granule biology. Arimoto et al. (2008) documented that Rack1, an activator of JNK signaling and subsequently apoptosis, is sequestered in arsenite-induced SGs, thereby preventing JNK activity. Rack1 is also sequestered in G3BP-induced stress granules, and G3BP inhibits activation of MTK1, an upstream kinase important for JNK activation. Active JNK has also been shown to be recruited to arsenite and heat-induced SGs along with a scaffolding molecule WDR62 (Wasserman et al., 2010). WDR62 and active JNK recruitment was not observed in G3BP-induced granules, whereas both Tia1 and TTP-induced granules colocalize with active JNK. It will be interesting for future work to examine Rack1, WDR62, and JNK activation in cells with small versus large G3BP-induced granules to determine whether differing localization and intensity exists. Phosphorylation of the decapping regulator Dcp1a by JNK has also been shown to reduce inclusion of Dcp1 in P-bodies (Rzeczkowski et al., 2011). Because JNK is known to act downstream of PKR to mediate innate immune responses (Garcia et al., 2006), the PKR–JNK signaling axis is an intriguing candidate pathway for our future work because it may be influenced by signaling from stress granules. Our finding that PKR is activated in cells with large G3BP-induced granules introduces a new signaling component into area of SG-dependent signaling that may help to clarify the role of JNK in mRNP biology. These questions are of interest for our future work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfections, and stress treatment

HeLa Tet-On cells were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/DMEM according to standard procedures. For all microscopy experiments, the cells were plated on glass coverslips at (1–1.3) × 105 cells per well in 12-well plates and grown overnight. Before transfections, medium was replaced with 2% FBS/DMEM and maintained throughout the experiment under those conditions. Transfections were conducted with FuGENE HD (Promega, Madison, WI) and 200 ng of plasmid per well for all experiments except DNA titration experiments. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2α, S/S and A/A homozygous mutants, and PKR−/− and HRI−/− MEFs were kind gifts from Randal Kaufman (Stanford Burnham Medical Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), Mauro-Costa Mattioli (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX), and Scot Kimball (Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA), respectively. GCN2−/−, PERK−/−, and corresponding wild-type control MEFs were originally developed in the laboratory of David Ron (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were maintained under the same conditions as HeLa Tet-On cells. Before transfections with FuGENE HD, MEFs were plated at 5 × 104 cells per well of a 12-well plate and grown overnight for transfection the following day. A 2-μg amount of plasmid per well was transfected due to the low transfection efficiency in MEFs. One microgram each of pSR-myc-PABP (Zheng et al., 2008) and pSport6-eIF4G-HA plasmids was transfected into each well of a 12-well plate and immunostained as detailed later. Oxidative stress treatments on cells involved adding arsenite to a final concentration of 200 μM for 30 min before fixation.

Plasmid construction

pG3BP-GFP-λN was generated by subcloning the λN coding sequence from pCI-λN-V5 (Ivanov et al., 2008) into the NotI and XbaI sites of pG3BP-EGFP (White et al., 2007). pGFP-λN was constructed by digesting pG3BP-GFP-λN with EcoRI and BamHI and using Klenow polymerase to generate blunt-ended DNA fragments. These fragments were subsequently ligated, and DNA preparations were produced with standard procedures.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (White and Lloyd, 2011). Briefly, 5′ biotinylated DNA probes were used to detect 5.8S rRNA, 28S rRNA, β-globin, and c-myc RNA. Probe sequences are as follows: 5.8S rRNA, 5′-ggaacccggggccgcaagtg cgttcgaagtgtcgatgatcaatgtgtcctgcaattc-3′; 28S rRNA, 5′-cggcgctgccgtatcgttccgcctgggc gggattctgacttagaggcgttc-3′; c-myc, 5′-tcttcctcatcttcttgctcttcttcagagtcgctgctggtggtgggcggtgtctcctcatgcagcactagg-3′; and β-actin, 5′-ccagaggcgtacagggatagcacagcctggatagcaacgtacatggctggggtgttgaaggtctcaaacatgatctgggtcatcttctcgcggttgg-3′. Probes were hybridized overnight at 42°C in a humidified chamber. Hybridized probes were detected with streptavidin 647 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and the signal was amplified with successive hybridizations with biotinylated anti-streptavidin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and streptavidin 647.

Ribopuromycilation assay

Cells were grown as described, and RPA was conducted essentially as described previously (David et al., 2011) using the 12D10 antibody directed against puromycin (Schmidt et al., 2009). Briefly, cells were pulsed with 50 μg/ml puromycin and 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for 5 min at 37°C before washing with permeabilization buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, 10 U/ml RNase Inhibitor [NEB New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA], and 1× protease inhibitor [ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA]) on ice and fixation with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature. The anti-puromycin antibody was incubated with coverslips at a concentration of 1:400–1:500 at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, cells were stained in accordance with the procedures outlined in the next subsection.

Immunofluorescence staining

Preparation of coverslips, mounting on slides, and incubation with antibodies against PABP, eIF4G, eIF3A, and Tia1 were performed as previously described (White et al., 2007; White and Lloyd, 2011). Anti–phospho-eIF2α antibody (#3597; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was used at 1:200–1:400 dilution on coverslips. Detection of Myc-PABP was performed using anti-Myc antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:500. eIF4G-HA was detected with anti-hemagglutinin antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at 1:1000. All secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:1000 dilution. Microscopy for figure preparation was performed on an Applied Precision DeltaVision deconvolution image restoration microscope (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA), and images for quantification were captured on a Nikon TE-2000 (Nikon, Melville, NY) at the Baylor College of Medicine Integrated Microscopy Core (Houston, TX). Images taken on both microscopes showed similar results.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed in accordance with standard procedures with the following antibodies: anti-GFP (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-G3BP (1:4000; Lloyd laboratory, Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-eIF2α (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-P-2alpha (119A11; 1:1500; Cell Signaling Technology).

Informatics

HeLa cell quantification was performed by outlining each cell using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for eIF2α staining. Pixel intensity was quantified and normalized to the cell area, and background from dead space for each image was subtracted. G3BP granule size was quantified by outlining each cell using Image Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) and setting upper and lower intensity thresholds so that all granules were included. This procedure generated area of the cell that was stress granule and total area of the cell. Cells were then classified according to the percentage total area occupied by stress granules. Classifications were as follows: 0–4% for no granules, 4–8% for small granules, and >8% for large granules. The minimum threshold size for large granules corresponded to ∼1.4 μM2.

For MEF quantification experiments, an automated pipeline was generated with Pipeline Pilot, version 8.5 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA), to detect cell boundaries for each cell in each field (>20 fields per genotype per condition). The intensity of the red (phospho-eIF2α channel) was quantified and normalized to the cell area to produce P-2alpha/cell area for each genotype with and without arsenite. The P-2alpha/cell area value without arsenite was then normalized against the P-2alpha/cell area value with arsenite. Cells were then manually sorted based on the presence or absence of granules and examined for quality control of Pipeline Pilot output.

For statistical analysis, two-tailed, equivariant Student's t tests were used to compare each group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Broughman of the Integrated Microscopy Core at Baylor College of Medicine for valuable input on microscopic techniques and quantification of images. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Public Health Service Grant AI50237 and an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA125123). L.C.R. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 AI07471.

Abbreviations used:

- eIF

eukaryotic initiation factor

- G3BP

RasGAP SH3-binding protein

- mRNP

messenger ribonucleoprotein

- RPA

ribopuromycilation assay

- SG

stress granule

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E12-05-0385) on July 25, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. Visibly stressed: the role of eIF2, TIA-1, and stress granules in protein translation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7:213–221. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0213:vstroe>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimoto K, Fukuda H, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Saito H, Takekawa M. Formation of stress granules inhibits apoptosis by suppressing stress-responsive MAPK pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/ncb1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan JR, Yoon JH, Parker R. Stress-specific composition, assembly and kinetics of stress granules in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:228–239. doi: 10.1242/jcs.078444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y, Kedersha N, Low WK, Romo D, Gorospe M, Kaufman R, Anderson P, Liu JO. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha-independent pathway of stress granule induction by the natural product pateamine A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32870–32878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A, Netzer N, Strader MB, Das SR, Chen CY, Gibbs J, Pierre P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. RNA binding targets aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to translating ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20688–20700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw F, Zhang T, Wauquier C, Huez G, Kruys V, Gueydan C. The cold-inducible RNA-binding protein migrates from the nucleus to cytoplasmic stress granules by a methylation-dependent mechanism and acts as a translational repressor. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:4130–4144. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever TE, Yang W, Astrom S, Bystrom AS, Hinnebusch AG. Modulation of tRNA(iMet), eIF-2, and eIF-2B expression shows that GCN4 translation is inversely coupled to the level of eIF-2.GTP.Met-tRNA(iMet) ternary complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6351–6363. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich DC, Lee JJ, Link AJ, Graumann J, Tirrell DA, Schuman EM. Labeling, detection and identification of newly synthesized proteomes with bioorthogonal non-canonical amino-acid tagging. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:532–540. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Gil J, Ventoso I, Guerra S, Domingo E, Rivas C, Esteban M. Impact of protein kinase PKR in cell biology: from antiviral to antiproliferative action. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:1032–1060. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil J, Rullas J, Garcia MA, Alcami J, Esteban M. The catalytic activity of dsRNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR, is required for NF-kappaB activation. Oncogene. 2001;20:385–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh KC, deVeer MJ, Williams BR. The protein kinase PKR is required for p38 MAPK activation and the innate immune response to bacterial endotoxin. EMBO J. 2000;19:4292–4297. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Zhou J. Survival motor neuron protein facilitates assembly of stress granules. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Yang M, May WS. RAX, a cellular activator for double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase during stress signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15427–15432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov PA, Chudinova EM, Nadezhdina ES. Disruption of microtubules inhibits cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein stress granule formation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov PV, Gehring NH, Kunz JB, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Interactions between UPF1, eRFs, PABP and the exon junction complex suggest an integrated model for mammalian NMD pathways. EMBO J. 2008;27:736–747. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Nie H, Silva AM, Williams BR, Li X. Poly(I-C)-induced Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)-mediated activation of NFkappa B and MAP kinase is through an interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-independent pathway employing the signaling components TLR3-TRAF6-TAK1-TAB2-PKR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16713–16719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Chen S, Gilks N, Li W, Miller IJ, Stahl J, Anderson P. Evidence that ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-tRNA(i)(Met))-deficient preinitiation complexes are core constituents of mammalian stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:195–210. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Cho MR, Li W, Yacono PW, Chen S, Gilks N, Golan DE, Anderson P. Dynamic shuttling of TIA-1 accompanies the recruitment of mRNA to mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1257–1268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Stoecklin G, Ayodele M, Yacono P, Lykke-Andersen J, Fritzler MJ, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Golan DE, Anderson P. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:871–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Yang YL, Flati V, Der S, Kadereit S, Deb A, Haque J, Reis L, Weissmann C, Williams BR. Deficient cytokine signaling in mouse embryo fibroblasts with a targeted deletion in the PKR gene: role of IRF-1 and NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 1997;16:406–416. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S, Zhang Y, Matthias P. The deacetylase HDAC6 is a novel critical component of stress granules involved in the stress response. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3381–3394. doi: 10.1101/gad.461107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, Vyas S, Rood JE, Bhutkar A, Sharp PA, Chang P. Poly(ADP-ribose) regulates stress responses and microRNA activity in the cytoplasm. Mol Cell. 2011;42:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loschi M, Leishman CC, Berardone N, Boccaccio GL. Dynein and kinesin regulate stress-granule and P-body dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3973–3982. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen E, Kedersha N, Song B, Scheuner D, Gilks N, Han A, Chen JJ, Anderson P, Kaufman RJ. Heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16925–16933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick WC. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation in eukaryotic systems. Gene. 2004;332:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokas S, Mills JR, Garreau C, Fournier MJ, Robert F, Arya P, Kaufman RJ, Pelletier J, Mazroui R. Uncoupling stress granule assembly and translation initiation inhibition. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2673–2683. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohn T, Kedersha N, Hickman T, Tisdale S, Anderson P. A functional RNAi screen links O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal proteins to stress granule and processing body assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1224–1231. doi: 10.1038/ncb1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RC, Sen GC. PACT, a protein activator of the interferon-induced protein kinase, PKR. EMBO J. 1998;17:4379–4390. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska J, Hansen SJ, Park N, Jamka K, Sarnow P, Gustin KE. Stable formation of compositionally unique stress granules in virus-infected cells. J Virol. 2010;84:3654–3665. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01320-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzeczkowski K, Beuerlein K, Muller H, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Schneider H, Kettner-Buhrow D, Holtmann H, Kracht M. c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylates DCP1a to control formation of P bodies. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:581–596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi N, Samuel CE. Protein kinase PKR catalytic activity is required for the PKR-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and amplification of interferon beta induction following virus infection. Virology. 2012;427:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MG, Martinez Tosar LJ, Loschi M, Pasquini JM, Correale J, Kindler S, Boccaccio GL. Staufen recruitment into stress granules does not affect early mRNA transport in oligodendrocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:405–420. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourriere H, Chebli K, Zekri L, Courselaud B, Blanchard JM, Bertrand E, Tazi J. The RasGAP-associated endoribonuclease G3BP assembles stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:823–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wasserman T, Katsenelson K, Daniliuc S, Hasin T, Choder M, Aronheim A. A novel c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-binding protein WDR62 is recruited to stress granules and mediates a nonclassical JNK activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:117–130. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Lloyd RE. Poliovirus unlinks TIA1 aggregation and mRNA stress granule formation. J Virol. 2011;85:12442–12454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05888-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Lloyd RE. Regulation of stress granules in virus systems. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Cardenas AM, Marissen WE, Lloyd RE. Inhibition of cytoplasmic mRNA stress granule formation by a viral proteinase. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Reineke LC, Lloyd RE. Poliovirus switches to an eIF2-independent mode of translation during infection. J Virol. 2011;85:8884–8893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00792-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynska A, Aigueperse C, Kress M, Dautry F, Weil D. The translational regulator CPEB1 provides a link between dcp1 bodies and stress granules. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:981–992. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Okabe K, Tani T, Funatsu T. Dynamic association-dissociation and harboring of endogenous mRNAs in stress granules. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:4087–4095. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Ezzeddine N, Chen CY, Zhu W, He X, Shyu AB. Deadenylation is prerequisite for P-body formation and mRNA decay in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:89–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200801196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.