Abstract

A 29-year-old lady receiving repeated blood transfusions for β thalassemia since childhood, presented with rapidly deteriorating symptoms of night blindness and peripheral visual field loss. She was recently commenced on high-dose intravenous desferrioxamine for reducing the systemic iron overload. Clinical and investigative findings were consistent with desferrioxamine-related pigmentary retinopathy and optic neuropathy. Recovery was partial following cessation of desferrioxamine. This report highlights the ocular side-effects of desferrioxamine mesylate and the need to be vigilant in patients on high doses of desferrioxamine.

Keywords: Desferrioxamine, ocular toxicity, optic neuropathy, pigmentary retinopathy

Thalassemia major is a hematological condition characterized by imbalance in the synthesis of alpha and β subunits of hemoglobin. It is estimated that worldwide there are over 2,000,000 transfusion-dependent people with thalassemia major with the majority of the cases in South-East Asia.[1] These patients require repeated blood transfusions from an early age to meet the oxygenation demand, resulting in systemic iron overloading. Desferrioxamine mesylate is the commonest iron chelating agent used in the management of iron toxicity and can be administered subcutaneously or intravenously.[2] Desferrioxamine can lead to significant ocular toxicity and regular ophthalmic screening is required for early detection and reversal of the disease.

Case Report

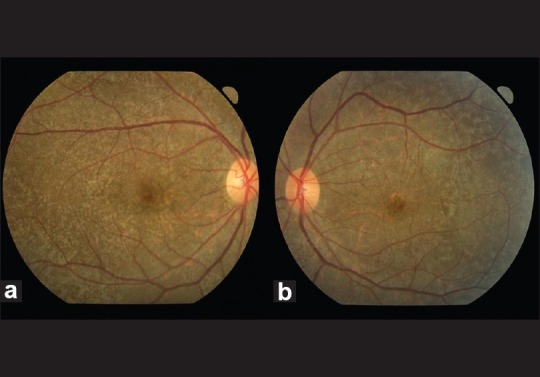

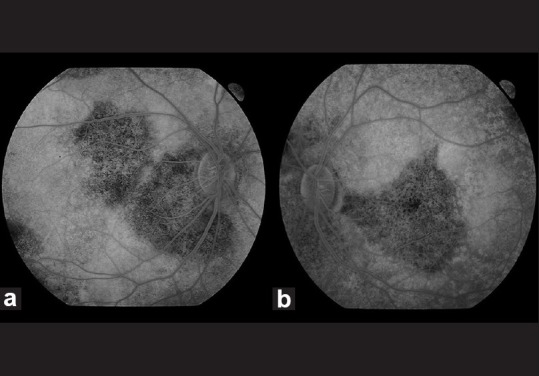

A 29-year-old Cambodian lady with a history of transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia from six years of age was referred for ophthalmic evaluation. She presented with recent onset of impaired color vision, constriction of visual fields and night blindness. She had been on subcutaneous desferrioxamine (40 mg/kg) six times per week since her initial transfusion. Ten weeks prior to her referral, she was started on intravenous desferrioxamine (50 mg/kg per day) for gross hepatic iron overload (serum ferritin level 5440 microgram/L, therapeutic index 0 .009). On examination, visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye (RE) and 20/40 in the left eye (LE). She had a left relative afferent pupillary defect and markedly diminished color vision in both eyes. Anterior segment examination was otherwise normal. Fundus examination revealed normal discs with widespread retinal pigment epithelium mottling [Fig. 1a and b]. On visual field testing, there was marked bilateral peripheral field loss leading to annular scotomas. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) showed speckled hyper-fluorescence with well-demarcated areas of blocked fluorescence [Fig. 2a and b]. Further evaluation with full-field electro-retinogram (ERG) showed marked bilateral reduction in amplitude for photopic, scotopic and 30-Hz flicker ERG. Electro-oculogram (EOG) revealed a diminished response (Arden index of 1.36 in the RE and 1.11 in the LE). The P100 latency period was more delayed in the left compared to the right on pattern visual evoked potential (VEP) testing.

Figure 1.

Color fundus photos demonstrating diffuse mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium at the posterior pole and mid-periphery in the right eye (a) and left eye(b)

Figure 2.

Fundus fluorescein angiogram (late venous phase) showing diffuse retinal hyper-fluorescence in both eyes along with blocked fluorescence in the peripapillary, macular and equatorial regions in the RE (a) and blocked fluorescence in the peripapillary, inferior papillomacular bundle and equatorial regions in the LE (b)

Desferrioxamine was stopped and replaced with deferipone (1 g three times per day). Four months later, there was marked recovery in color vision in both eyes; the visual acuities remained unchanged. Retinal pigmentary changes remained status quo. Perimetry showed partial improvement in the LE whilst RE fields remained unchanged. She was subsequently re-commenced on subcutaneous desferrioxamine 2.5 g twice per week. Follow-up over one year showed no further improvements in visual function.

Discussion

Desferrioxamine mesylate is a widely used chelating agent in managing patients with chronic iron overload, acute iron poisoning and aluminum toxicity. As illustrated by this report, patients on desferrioxamine can present with acute/sub-acute deterioration in visual acuity and color vision, night blindness, scotomas or constricted fields. The ocular toxicity is postulated to be due to the direct effect of desferrioxamine, chelation of ions (iron, copper, aluminum) on the retinal pigment epithelial with resultant dysfunction or due to defective vasoregulation.[3] Ocular side-effects include cataracts, retrobulbar optic neuritis, pigmentary retinopathy, bull's eye maculopathy and vitelliform maculopathy.[4–6] The pigmentary retinopathy is classically macular or peripheral but can rarely present in the paramacular, papillomacular or peripapillary pattern.[5] It is still unclear whether ocular toxicity is dose-dependent or not; however, existing literature as well as our experience with this patient shows that those with lower iron loads and desferrioxamine dosage higher than 50 mg/kg/day are at increased risk for developing systemic toxicity.[3,7] As ocular toxicity can be asymptomatic, all patients on desferrioxamine should have baseline visual acuities, color vision, visual fields, FFA, EOG and ERG. During the follow-up phase, diffuse outer retinal fluorescence on FFA is a useful marker for ongoing disease activity,[5] whilst EOG and ERG are helpful in monitoring the retinal dysfunction. Regular ophthalmic screening at three-monthly intervals along with monthly monitoring of serum ferritin levels and maintenance of the therapeutic index level of desferrioxamine (daily dose per body weight (mg/kg) divided by serum ferritin (microgram/l)) at levels < 0.025 can help in prevention and reversal of ocular toxicity.[8,9] It is also interesting to observe that a presenting therapeutic index level of desferrioxamine below 0.04 can be indicative of better visual prognosis.[4,6]

In conclusion, heightened awareness amongst ophthalmologists and regular ophthalmic screening is required in patients receiving desferrioxamine to avoid delayed diagnosis and management of desferrioxamine-related optic neuropathy and retinal dysfunction.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Sciences Ltd; 2001. The Thalassamia Syndromes. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89:739–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora A, Wren S, Gregory Evans K. Desferrioxamine related maculopathy: A case report. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:386–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies SC, Marcus RE, Hungerford JL, Miller MH, Arden GB, Huehns ER. Ocular toxicity of high-dose intravenous desferrioxamine. Lancet. 1983;2:181–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haimovici R, D’Amico DJ, Gragoudas ES, Sokol S. The expanded clinical spectrum of deferoxamine retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:164–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00947-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis BA, Porter JB. Long-term outcome of continuous 24-hour deferoxamine infusion via indwelling intravenous catheters in high-risk beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2000;95:1229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter JB. A risk-benefit assessment of iron-chelation therapy. Drug Saf. 1997;17:407–21. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199717060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai TY, Lee GK, Chan WM, Lam DS. Rapid development of severe toxic retinopathy associated with continuous intravenous deferoxamine infusion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:243–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.080119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter JB, Jaswon MS, Huehns ER, East CA, Hazell JW. Desferrioxamine ototoxicity: Evaluation of risk factors in thalassaemic patients and guidelines for safe dosage. Br J Haematol. 1989;73:403–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb07761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]