Abstract

We report a case of isolated homonymous hemianopsia due to presumptive cerebral tubercular abscess as the initial manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. A 30-year-old man presented to our outpatient department with sudden loss of visibility in his left visual field. He had no other systemic symptoms. Perimetry showed left-sided incongruous homonymous hemianopsia denser above the horizontal meridian. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed irregular well-marginated lobulated lesions right temporo-occipital cerebral hemisphere and left high fronto-parietal cerebral hemisphere suggestive of brain tubercular abscess. Serological tests for HIV were reactive, and the patient was started only on anti-tubercular drugs with the presumptive diagnosis of cerebral tubercular abscess. Therapeutic response confirmed the diagnosis. Atypical ophthalmic manifestations may be the initial presenting feature in patients with HIV infection. This highlights the need for increased index of suspicion for HIV infection in young patients with atypical ophthalmic manifestations.

Keywords: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cerebral abscess, human immunodeficiency virus, homonymous hemianopsia, initial ophthalmic manifestation, tubercular abscess, tuberculosis

Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may occur as a result of primary HIV-associated optic neuropathy, opportunistic infections or central nervous system (CNS) malignancy. Such neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations are, however, uncommon.[1–3] We herein report a young patient who presented with an isolated visual field defect as the presenting sign of HIV infection. Imaging studies and therapeutic response to anti-tubercular therapy indicated tubercular abscess as the cause of the field defect.

Case Report

A 30-year-old man presented to our outpatient department with sudden loss of visibility in his left visual field for one week. There was a history of headache and low-grade fever for five weeks. He had no other neurological or systemic signs and symptoms. On ocular examination Snellen visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes, ocular adnexa and motility were also normal in both eyes. The pupils of both eyes were equal, round, regular. Direct and consensual light reflexes were symmetrical and normal in both eyes. Ocular media were clear and fundus examination did not show any abnormalities of the optic nerve head or the retina in both eyes. On confrontation visual field testing left-sided field defect was noted in both eyes. Color vision and contrast sensitivity were normal in both eyes.

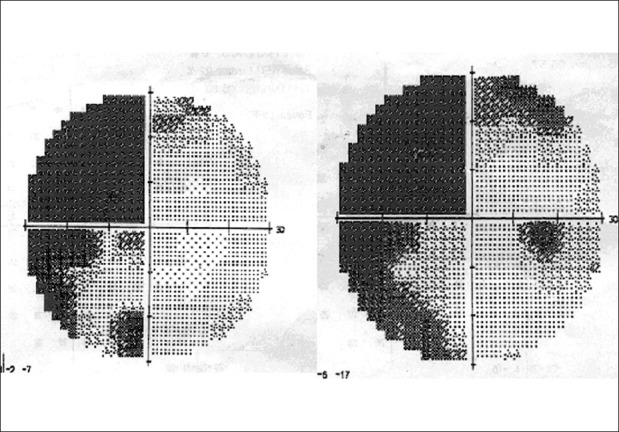

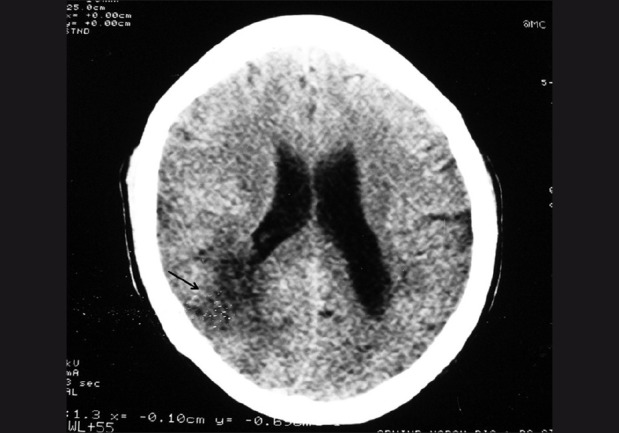

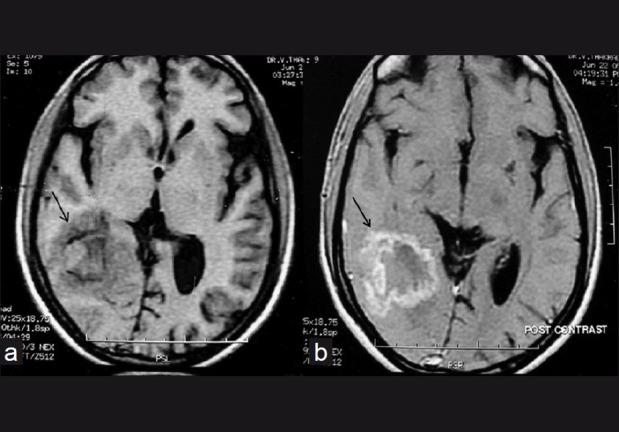

Automatic static threshold perimetry (Humphrey Field Analyser) [Fig. 1] showed left-sided incongruous homonymous hemianopsia denser above the horizontal meridian. Brain computed tomography (CT) scan showed a hypodense lesion in the right parieto-temporal lobe [Fig. 2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed irregular well-marginated lobulated lesions with mild perifocal edema of altered signal intensity showing irregular contrast enhancement in the right temporo-occipital (39×34×24 mm3) and left high fronto- parietal region (26×22×17 mm3) [Fig. 3]. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and chest X- ray were normal. There was no evidence of retroperitoneal and mediastinal lymph node enlargement. A repeat systemic and neurologic examination was unremarkable. Serological tests for HIV were reactive. Other investigations showed a CD4 (cluster differentiation 4) count of 396 cells/μl, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 60 mm/1sth, negative sputum for acid fast bacillus (AFB) {Ziehl-Nielsen staining} and negative toxoplasma IgG (Immunoglobulin G) titers.

Figure 1.

Humphrey visual field showing left-sided homonymous incongruous hemianopsia denser above the horizontal meridian

Figure 2.

Non-contrast CT shows a hypodense lesion (arrow) in the right parieto-occipital region with mild mass effect on the posterior horn of the right lateral ventricle

Figure 3.

Pre-treatment Axial T1W image (TR/TE-340/11) shows the lesion in the right temporo-occipital region (arrow) with a periphery which is isointense to grey matter, an incomplete hypointense rim and a mixed iso and hyperintense centre (a). Axial contrast-enhanced T1W image shows irregular ring enhancement of the lesion (arrow) (b)

The patient was started only on anti-tubercular drugs with the presumptive diagnosis of primary cerebral tubercular abscess. The regime consisted of an intensive phase of two months with Isoniazid (300 mg/day), Rifampicin (600 mg/ day), Pyrazinamide (1500 mg/day), Ethambutol (800 mg/day) followed by a continuation phase of 10 months with Isoniazid (300 mg/day), Rifampicin (600mg/day) and pyridoxine (20 mg/day). After four weeks of the intensive phase of anti-tubercular therapy (ATT), the patient's initial constitutional symptoms improved. MRI after two-month intensive phase followed by 10-month continuation phase of ATT showed significant decrease in the size of the lesions which measured 21× 17 mm for the right and 11× 9 mm for the left with minimal edema. In addition the central cores of the lesions were now hypointense on T2-weighted (T2W) images [Fig. 4]. But repeat perimetry after one year did not reveal any significant improvement in visual fields.

Figure 4.

Follow-up axial T2W MRI after one year reveals a significant decrease in the size of the lesion (arrow) which now has a hypointense centre

Discussion

Neuro-ophthalmological features are often evident in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.[1–11] Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of cerebral mass lesions in patients with AIDS. It usually develops in patients with CD4+ counts < 100 cells/μL. In toxoplasmosis, multiple lesions commonly involve the cerebral white matter or deep grey matter.[4–6] In our patient, the larger lesion in the right hemisphere extended from the peri-ventricular area up to the cortical grey matter whereas the smaller lesion in the left high frontal lobe was cortical. Patient had normal CD4 counts and serological titer for toxoplasma was negative thus ruling out the possibility of cerebral toxoplasmosis.

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) usually occurs in AIDS’ patients with CD4+ counts < 50 cells/μl. Appearance of PCNSL is an isointense to hypointense multiple mass on T1-weighted MRI images with post-gadolinium intense diffuse enhancement and variable intensity on T2. A ring-like enhancing pattern with subependymal spread is seen. Often, there is little or no surrounding edema.[6–8] Hence PCNSL was unlikely in our patient.

Cerebral manifestations of tuberculosis include meningitis and focal intra-parenchymal lesions like tuberculomas and abscess. Tubercular space-occupying lesion located within the cerebral hemispheres may produce visual loss from interruption of the post-geniculate visual pathways. Homonymous visual field defects or cortical blindness may be produced by such lesions. Neuroretinitis, optic neuropathy, papilledema, abnormal saccades and pursuit, and ocular motor nerve palsy were also reported as neuro-ophthalmological complications of CNS tuberculosis in AIDS.[8–12] Cerebral tuberculosis may develop even in the presence of higher CD4 count. Tuberculomas are generally multiple, one centimeter or less in size without minimal mass effect and edema. Tuberculomas have a hypointense centre with an isointense rim on T2-weighted MRI. Unlike tuberculomas, tubercular abscesses are solitary, larger, with significant mass effect and edema. Tubercular abscesses have a hyperintense centre on T2 due to central liquifactive necrosis and pus formation.[8–10]

In our case, the solitary lesion in both cerebral hemispheres with irregular ring-enhancing margin with initial hyperintense core on T2 involving optic radiation is presumptive of tubercular abscess. In addition, given the fact that Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the most common opportunistic infection in AIDS’ patients in India, this patient was treated with only standard anti-tubercular drugs.[3,13] The patient's constitutional symptoms improved within one month. On follow-up the lesions were significantly decreased in size with a hypointense core and a hyperintense rim on T2W images. The therapeutic response in our patient confirmed that the most likely cause of his symptoms was a tubercular abscess in the right temporo-parieto-occipital area, causing left-sided isolated homonymous hemianopsia.[12]

After an extensive search in PubMed, we did not find any report of isolated incongruous homonymous hemianopsia due to CNS tubercular abscess as initial manifestation of HIV infection. This report highlights the role of imaging and therapeutic trial in confirming the diagnosis. It also highlights the importance of early diagnosis of subclinical neuro-ophthalmological signs that's may be life saving in fatal disease like CNS tubercular abcess.

References

- 1.Friedman DI. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Neurol Clin. 1991;9:55–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vrabec TR. Posterior segment manifestations of HIV/AIDS. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:131–57. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gharai S, Venkatesh P, Garg S, Sharma SK, Vohra R. Ophthalmic manifestations of HIV infections in India in the era of HAART: Analysis of 100 consecutive patients evaluated at a tertiary eye care center in India. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:264–71. doi: 10.1080/09286580802077716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RM, Rosenbloom S, Perrett LV. Neuroradiologic findings in AIDS: A review of 200 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:977–83. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trenkwalder P, Trenkwalder C, Feiden W, Vogl TJ, Einhäupl KM, Lydtin H. Toxoplasmosis with early intracerebral hemorrhage in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Neurology. 1992;42:436–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.2.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dina TS. Primary central nervous system toxoplasmosis versus Lymphoma in AIDS. Radiology. 1991;179:823–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.3.2027999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine AM. Epidemiology, clinical characteristic, and management of AIDS related lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1991;5:331–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martín-Luquero M, Marcos LA, Freijanes N, Pérez-Castrillón JL. A focal central nervous system mass in an AIDS patient with tuberculous meningitis. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:697–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.889.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malasky C, Reichman LB. Long-term follow-up of tuberculoma of the brain in an AIDS patient. Chest. 1992;101:278. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.1.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiteman M, Espinoza L, Post MJ, Bell MD, Falcone S. Central nervous system tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients: Clinical and radiographic findings. AJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1319–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mwanza JC, Nyamabo LK, Tylleskär T, Plant GT. Neuro-ophthalmological disorders in HIV infected subjects with neurological manifestations. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1455–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.044289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxena R, Menon V, Sinha A, Sharma P, Kumar DA, Sethi H. Pontine tuberculoma presenting with horizontal gaze palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:276–8. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000249321.34733.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. World Health Organization. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: treatment guidelines for a public health approach. 2003 revision; pp. 40–2. [Google Scholar]