Plants are continuously exposed to changes in the light spectrum, both short term and long term, due to changes in weather, the sun angle, and sun shade conditions. Of course, the absorption of incident light by a leaf is strongly wavelength dependent because different leaf pigments have different absorptance spectra; blue and red light are the most strongly absorbed, and leaves appear green because a relatively large proportion of green wavelengths are reflected rather than absorbed. However, even on an absorbed light basis, the quantum yield for CO2 fixation is wavelength dependent, with red light (600 to 640 nm) being the most effective and blue light (420 to 500 nm) the least effective. Causes that have been identified for the wavelength dependence of quantum yield of CO2 fixation include differential absorption by photosynthetic carotenoids and nonphotosynthetic pigments and an imbalanced excitation of the two photosystems (Terashima et al., 2009). One consequence of the latter cause is that plants have the capacity to optimize quantum yield for photosynthesis under variable conditions by altering photosystem composition and stoichiometry.

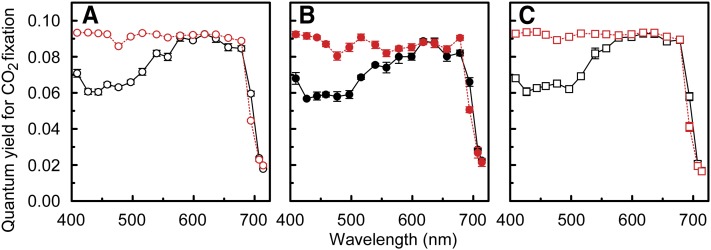

Hogewoning et al. (pages 1921–1935) present a detailed investigation of the underlying causes of the wavelength dependence of the quantum yield for CO2 fixation and its capacity for adaptation to the light spectrum of the growth environment. In contrast with previous studies, the authors assessed the wavelength dependence of quantum yield on an absorbed light basis (termed α) under spectrally different growth light conditions (e.g., sunlight, shade light, and blue light) and conducted parallel measurements of quantum yields for photosystem I and photosystem II electron transport and photosystem stoichiometry. They find that α largely results from two processes: (1) the imbalance in light absorption between the two photosystems at a given wavelength and (2) light absorption by photosynthetic carotenoids and nonphotosynthetic pigments in the blue-green region. They show in particular that photosystem efficiency balance, reflecting the ratio of photosystem I:photosystem II reaction centers, has a strong impact on α (see figure). Detailed measurements also allowed the authors to quantify enhancement effects, the observation that the quantum yield of a combination of wavelengths is higher than the sum of the parts. They show that enhancement effects indeed can result in a major increase in the quantum efficiency of CO2 fixation, relative to illumination with single wavelengths, especially for shade light spectrum–grown leaves. The absolute maximum quantum yield for CO2 fixation (or O2 evolution) has long been debated (Govindjee, 1999). Hogewoning et al. measured a maximum quantum yield of 0.093 CO2 fixed per absorbed photon, in line with previously reported values, but correction for quantum yield losses due to imbalances in photosystem excitation increased the maximum value of α to 0.0955 for all growth light treatments.

Underlying causes of the wavelength dependence of quantum yield. Quantum yield for CO2 fixation for 18 different wavelengths calculated from gas-exchange measurements (black solid lines) and from the in vivo efficiency balance between the two photosystems (red dotted lines). The difference between the values obtained by the two different methods at wavelengths <580 nm represents quantum yield losses attributable to light absorption by photosynthetic carotenoids and nonphotosynthetic pigments. (A), (B), and (C) correspond to leaves grown under the sunlight spectrum, the shade light spectrum, and blue irradiance, respectively. (Reprinted from Hogewoning et al. [2012], Figure 8.)

This work represents a major advance in photosynthesis research. A potential application of the results can be derived from the prediction that crop yields might be improved by breeding varieties with a lower nonphotosynthetic pigment content. This may apply especially under controlled conditions (e.g., greenhouse-grown crops), where the presumed protective properties of blue light–absorbing phenolics against factors such as herbivory and UV light can be substituted by alternative measures.

References

- Govindjee (1999). On the requirement of minimum number of four versus eight quanta of light for the evolution of one molecule of oxygen in photosynthesis: A historical note. Photosynth. Res. 59: 249–254.

- Hogewoning S.W., Wientjes E., Douwstra P., Trouwborst G., van Ieperen W., Croce R., Harbinson J. (2012). Photosynthetic quantum yield dynamics: From photosystems to leaves. Plant Cell 24: 1921–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I., Fujita T., Inoue T., Chow W.S., Oguchi R. (2009). Green light drives leaf photosynthesis more efficiently than red light in strong white light: revisiting the enigmatic question of why leaves are green. Plant Cell Physiol. 50: 684–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]