Abstract

In recent years, cognitive neuroscience has been concerned with the role of the corpus callosum and interhemispheric communication for lower-level processes and higher-order cognitive functions. There is empirical evidence that not only callosal disconnection but also subtle degradation of the corpus callosum can influence the transfer of information and integration between the hemispheres. The reviewed studies on patients with callosal degradation with and without disconnection indicate a dissociation of callosal functions: while anterior callosal regions were associated with interhemispheric inhibition in situations of semantic (Stroop) and visuospatial (hierarchical letters) competition, posterior callosal areas were associated with interhemispheric facilitation from redundant information at visuomotor and cognitive levels. Together, the reviewed research on selective cognitive functions provides evidence that the corpus callosum contributes to the integration of perception and action within a subcortico-cortical network promoting a unified experience of the way we perceive the visual world and prepare our actions.

Keywords: Corpus callosum, Crossed-uncrossed difference (CUD), Redundant targets effect (RTE), Functional lateralization, Stroop, Hierarchical perception, Attention, Neuroimaging

The pioneering work of Norman Geschwind (1965) introduced the idea that deficits in language, learning, emotion and action are manifestations of a ‘disconnection syndrome’ that result not only from cortical lesions but from white matter lesions disrupting the connectivity between sensory and association cortices. Geschwind’s model included both connections between brain regions and the functional specialization of association cortices (Catani and ffytche 2005). The concept of a distributed neural circuitry has inspired investigations into how brain connectivity enables hemispheric specialization for mental processes, which range from basic perception (Nassi and Callaway 2009) to higher cognitive functions and consciousness (Galaburda and Geschwind 1980; Zaidel and Iacoboni 2003). A common theme of these investigations is how perceptions, thoughts and actions emerge from the integration of sensory, cognitive and motor inputs received or processed in separate cerebral hemispheres.

Pathways Subserving Intra-and Interhemispheric Communication

Cortico-cortical communication within and between hemispheres relies on a widespread white matter network that also connects to subcortical gray matter. The white matter tracts can be divided in association pathways that are intrahemispheric fibers connecting cortices of the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital lobes and commissural pathways that are interhemispheric fibers connecting the cortical areas of both hemispheres (Aralasmak et al. 2006). Geschwind’s disconnection hypothesis assumed that not cortical damage alone but cortical disconnection by white matter fiber pathway disruption makes substantial contributions to functional deficits in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Intrahemispheric Communication

Several cortico-cortical association and cortico-subcortical projection pathways ensure communication within each hemisphere. Superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) fibers, for example, connect temporo-parieto-occipital regions with the frontal lobe. While left-hemispheric SLF fibers have been related to speech (Duffau et al. 2002) and language comprehension (Tanabe et al. 1987), right-hemispheric fibers have been related to the spatial-attention network (Doricchi and Tomaiuolo 2003). The inferior longitudinal fasciculi connect temporal to occipital lobes in each hemisphere and have been associated with higher-order visual functions such as object recognition (left-lateralized; Salvan et al. 2004), face recognition, and visually evoked emotions (bilateral or right-lateralized; Bauer 1982; Habib 1986). The inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi connect visual association areas with the frontal eye fields, and there is some evidence that they mediate simultaneous perception intrahemipherically needed for selecting visual information in crowded scenes (right-lateralized or bilateral; Battelli et al. 2003; Rizzo and Vecera 2002). The cingulum is a large fiber bundle of the limbic system connecting cingulate and hippocampal gyri with amygdala, nucleus accumbens, thalamus and frontal cortices, areas involved in emotion, reward and executive control. Thus, each hemisphere has extensive cortico-cortical and cortico-subcortical connections (Mori et al. 2002). The myriad information transferred via these fiber tracts and processed in each hemisphere is also available for integration between the two hemispheres via commissural pathways to form a unified perception.

Interhemispheric Communication

The major commissural pathway is the corpus callosum (CC), a thick band of white matter fibers consisting of more than 200 million axons connecting the right and left cerebral hemispheres of the brain and playing an important role in interhemispheric transfer of information (Aboitiz et al. 1992; Banich 1995; Banich and Shenker 1994; Innocenti 1986; Schmahmann and Pandya 2006). Although callosal fibers mostly project to homotopic regions of the hemispheres (e.g., parietal lobe to parietal lobe, etc.) along an anterior-posterior gradient (McCulloch and Garol 1941; Putnam et al. 2008), some callosal fibers also project to heterotopic regions (e.g., parietal to frontal lobe, etc.) (Clarke and Zaidel 1994; Cook 1984; Rakic and Yakovlev 1968). The CC has no macroscopic anatomical landmarks that delimit anatomical and functionally distinct regions (Hofer and Frahm 2006). It has been geometrically divided into three regions (Duara et al. 1991; Sullivan et al. 2002) (1) an anterior part (genu+rostrum) that connects frontal and premotor regions of the two hemispheres, (2) a middle part (body) that interconnects motor, somatosensory and parietal areas, and (3) a posterior part of the corpus callosum (splenium) that interconnects temporal and occipital cortices (Fig. 1) (Park et al. 2008; Putnam et al. 2009; Wahl et al. 2007) but there have been numerous geometric models for differentiating sections of the CC (e.g., Ryberg et al. 2007; Witelson 1989; see also Chanraud et al., in this issue). Although our understanding of the organization of CC white matter pathways has considerably increased (Poupon et al. 2001; Putnam et al. 2009) in the advent of recent development of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) techniques (Baird and Warach 1998; Le Bihan et al. 2001; Le Bihan 2003; Moseley et al. 1990; Pfefferbaum et al. 2003; Sullivan and Pfefferbaum 2003; Wahl et al. 2007; Westerhausen et al. 2009) relatively little is still known about the relation between callosal regions and interhemispheric integration of sensory and cognitive information (Bloom and Hynd 2005).

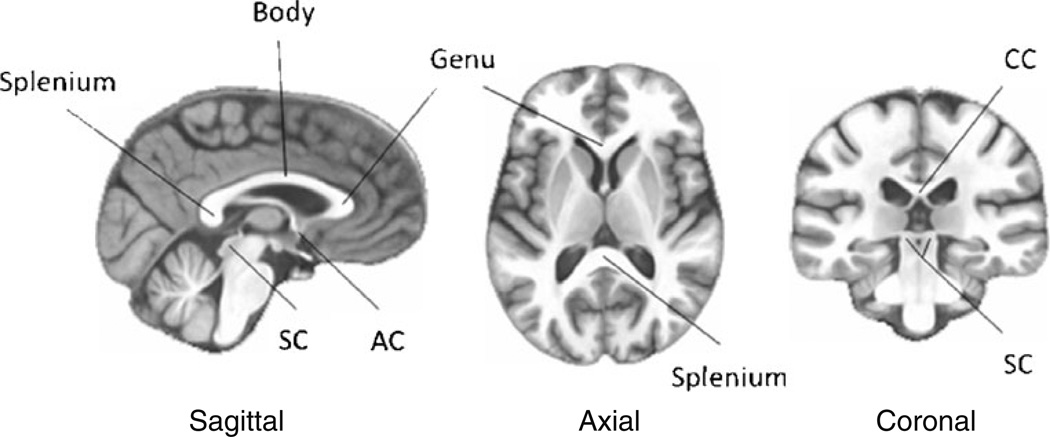

Fig. 1.

Sagittal, axial and coronal section of the human brain (The SRI24 multichannel atlas of normal adult human brain structure; Rohlfing et al. 2010) illustrating the anterior (genu), middle (body) and posterior (splenium) sectors of corpus callosum (CC). Other illustrated interhemispheric connections are the anterior commissure (AC) and the superior colliculi (SC)

In humans, primary visual, auditory and motor cortex functions are highly lateralized with the left cerebral hemisphere processing right-sided sensory input and motor output and the right cerebral hemisphere processing left-sided sensory input and motor output. Input from both hemispheres needs to be integrated and selected for further higher-order cognitive processing and for a unified motor response (Stephan et al. 2003). From an evolutionary standpoint the CC is assumed to play an integral role in the development of higher cognitive processes and hemispheric specialization (Doron and Gazzaniga 2008). During human evolution, brain and CC size increased considerably. Some studies suggest that the communication speed between the two hemispheres is faster with increased brain size (Caminiti et al. 2009; Innocenti 1995) and that larger callosal area indicate faster interhemispheric communication (Jancke and Steinmetz 1994; Paul et al. 2007), while others suggest a progressive slowing of interhemispheric communication in larger brains (Ringo et al. 1994). Interestingly, recent animal studies have suggested that more lateralized brains are better to act directly on many sources of information at the same time (Magat and Brown 2009). For example, chimpanzees that use one hand to fish termites out of their mounds are more efficient than chimpanzees that are ambidextrous (Marchant and McGrew 1996).

Although the CC is the largest interhemispheric commissure, other commissural pathways include the anterior, hippocampal, posterior, habenuar, and tectal commissures and also the two sides of the brainstem reticular formation have extensive connections (Aralasmak et al. 2006). The superior colliculus and the tectal commissure are thought to play a role in visual transfer and to maintain interhemispheric transfer of basic visual information in patients with callosal agenesis, callosotomy and commissurotomy (Tardif and Clarke 2002). Nevertheless, studies in acallosal and split-brain patients state quite clearly that absence or loss of CC integrity contributes to impairment in sensory and cognitive integration (Fabri et al. 2001; Yamauchi et al. 1997). In fact, many years of research have demonstrated a relationship between callosal connectivity and prolonged interhemispheric transfer time in split-brain patients and in acallosal patients (Corballis 1998; Iacoboni et al. 2000; Marzi et al. 1991; Mooshagian et al. 2009; Paul et al. 2007; Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1995; Roser and Corballis 2002). Less radical disruption of callosal fiber integrity such as seen in patients with multiple sclerosis (Warlop et al. 2008), schizophrenia (Schrift et al. 1986; Woodruff et al. 1997), alcoholism (Hutner and Oscar-Berman 1996; Schulte et al. 2004, 2005, 2008), autism (Keary et al. 2009), and even in normal aging (Jeeves and Moes 1996; Schulte et al. 2005) has been also associated with prolonged interhemispheric transfer time (IHTT).

Callosal Function in Interhemispheric Communication

Different callosal functions have been proposed for interhemispheric communication. For example, the hemispheric insulation view states that the CC acts as a shield to reduce interference and to prevent potentially harmful intrusions from the opposite hemisphere (Kinsbourne and Hicks 1978; Liederman and Meehan 1986), whereas the callosal inhibition view assumes that stimulus-driven activity in one hemisphere suppresses activity in the other, thereby, for instance, causing a shift in attention to the contralateral side of the more activated hemisphere (Chiarello and Maxfield 1996). Callosal reciprocal inhibition may further equilibrate activation and prevent attention from being skewed to the contralateral side when one hemisphere is disproportionately active (Kinsbourne 2003). Interhemispheric cooperation between the hemispheres has been assumed to be more advantageous than within hemispheric processing in situations of high processing demand (Banich and Belger 1990). Interhemispheric sharing of information and the need for inhibiton or isolation from each other are not mutually exclusive and may depend on the kind of information processed. It is, for example, well established that the two hemispheres have different functions, with a left-hemispheric superiority in processing speech and language and a right-hemispheric superiority for certain visuospatial functions. Thus, when one hemisphere is superior to the other in processing specific information, intrahemispheric processing may be more advantageous, and callosal isolation or inhibition would increase processing efficiency and performance. By contrast, when both hemispheres are qualified to process the same information, sharing of hemispheric resources may be more advantageous and require callosal interhemispheric cooperation (Bloom and Hynd 2005).

Interhemispheric Communication for Visuomotor and Cognitive Functions

First, we will provide an overview of the role of the CC in lower-level processes and interhemispheric visuomotor integration as documented in recent behavioral and neuroimaging studies on the crossed-uncrossed difference, an estimation of interhemispheric transfer time (Poffenberger 1912), and on redundancy gain, a measure of visuomotor integration (Miller 1991; Mordkoff and Yantis 1991, 1993). Secondly, we will explore the contribution of the CC to higher-order cognitive functions, such as attention and executive control, and to integrating the left hemisphere, specialized for processing local details and language, and right hemisphere, specialized for processing holistic, global forms and spatial attention functions (Aziz-Zadeh et al. 2006; Gazzaniga 2000; Gazzaniga 2005; Hugdahl and Davidson 2003).

The Role of the CC for the Integration of Lower-Level Functions

Interhemispheric Transfer Time and the Corpus Callosum

Approaches describing and analyzing interhemispheric integration of information in humans include simple reaction time (RT) tasks in which targets are presented in the same (uncrossed) or opposite (crossed) visual field in relation to the responding hand (Poffenberger 1912; Zaidel and Iacoboni 2003). The difference between crossed and uncrossed reaction times relative to the responding hand (Crossed-Uncrossed Difference, CUD; crossed: left hemifield/right hand and right hemifield/left hand; uncrossed: left hemifield/left hand, right hemifield/right hand) provides an index of interhemispheric transfer time (IHTT), because the uncrossed response can be processed within the same hemisphere, whereas crossed responses require transfer of visuomotor information between hemispheres via the CC (Corballis 1998, 2002; Iacoboni and Zaidel 1995, 2004; Mooshagian et al. 2008; Pollmann and Zaidel 1998; Tettamanti et al. 2002).

In normal subjects the CUD is approximately 4–6 ms (Marzi et al. 1991), and shorter in younger than older adults (Schulte et al. 2004; Reuter-Lorenz and Stanczak 2000). Hanajima et al. (2001) found that muscle responses to transcranial stimulation over the left-hand motor cortex can be facilitated when transcranial stimulation has been applied 4–5 ms earlier over the right-hand motor cortex, about the same time as the CUD value estimated from behavioral studies in normal subjects. In acallosal and commissurotomized patients the CUD is prolonged (~30–70 ms) because of longer reaction times to lateralized stimuli in the crossed compared to the uncrossed condition owing to the indirect route required for interhemispheric transfer (e.g., Berlucchi et al. 1971; Berlucchi et al. 1995; Clarke and Zaidel 1989; Forster and Corballis 1998, 2000).

There is an ongoing debate whether the CUD is based solely on the anatomy of callosal fibers or whether the CUD may also be mediated by attentional components (Mooshagian et al. 2008). Support for an anatomical interpretation of the CUD comes from DTI studies. DTI yields estimates of fractional anisotropy (FA) that indexes white matter structural integrity and measures the orientational displacement and distribution of water molecules in vivo across tissue components (Pierpaoli and Basser 1996). FA is typically higher in fibers with a homogeneous or linear structure than in tissue with an inhomogenous structure, such as areas with pathology (Lansberg et al. 2001; Neumann-Haefelin et al. 2000) or crossing fibers (Pfefferbaum and Sullivan 2003; Virta et al. 1999). DTI studies have revealed correlations between subtle variations in regional white matter callosal microstructure and behavioral measures of IHTT and cognitive ability (Muetzel et al. 2008; Schulte et al. 2005; Sullivan et al. 2010). In adolescence (9–23 years), for example, age-related increases in callosal FA were associated with better bimanual coordination using an alternating finger-tapping task (Muetzel et al. 2008), and in adults (20–78 years), age-related white matter degradation correlated with poorer motor and cognitive performance (Sullivan et al. 2010). In normal aging, Schulte et al. (2005) found that low FA in callosal genu and splenium correlated with longer IHTT measured with the CUD (Poffenberger paradigm, 1912). By contrast, Westerhausen et al. (2006) did not find a correlation between callosal diffusion parameters and the CUD (2.5 ms) but did find negative correlations between mean diffusion and IHTT, derived from the P100 event-related potential. Methodological variables such as stimulus parameters (eccentricity and luminance, fixation control, forehead-chin rest) (Schiefer et al. 2001), calculation of the CUD using median or mean reaction times (RT) (Braun et al. 1995), and a reduced variance by choosing a homogenous sample of young male healthy college students (Westerhausen et al. 2006) may have contributed to the relative insensitivity of behavioral CUD measures (Bashore 1981).

There is also evidence that attention influences CUD measures. In a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, Weber et al. (2005) tested healthy right-handed volunteers with a modified Poffenberger paradigm in which the attentional focus was implicitly directed toward the contra-or ipsilateral hemifield relative to the responding hand. They found that crossed relative to uncrossed trials (CUD) activated anterior callosal area, but when attentionally manipulated, activated superior colliculi and right superior parietal cortex, a region typically associated with attentional shifts. This is consistent with findings of Iacoboni and Zaidel (2004) suggesting that shifts in spatial attention (Corbetta et al. 1995) can critically influence sensory-motor integration (Creem-Regehr 2009). Activations of premotor and parietal cortex regions observed with fMRI also map to fibers linking through the mid-body and anterior regions of the CC (Iacoboni and Zaidel 2004; Schulte et al. 2005). Recently, Mooshagian and colleagues examined the influence of spatial attentional shifts on CUD in patients with agenesis of the CC and complete commissurotomy (2009) and in healthy subjects (2008) by alternating between natural (arms uncrossed) and unnatural arm positions (arms crossed). The CUD was smaller with arms crossed (unnatural arms position) than uncrossed (natural arms position) in patients as well as normal controls indicating that the relative arm position is sufficient to modulate the CUD even in the absence of the CC.

To summarize, the CUD indexes the time required for information to cross the CC (Berlucchi et al. 1995; Fendrich et al. 2004), but there is also evidence that the CUD can be modulated by spatial attention (Braun et al. 1995; Mooshagian et al. 2008). Other possible factors that influence the CUD are age (Jeeves and Moes 1996; Schulte et al. 2004; Reuter-Lorenz and Stanczak 2000) and sex differences in callosal structure and size (Luders et al. 2003). In a recent event related potential (ERP) experiment, Moes et al. (2007) revealed shorter and more symmetrical IHTT for women than men. It appears that IHTT between hemispheres is faster from right-to-left than from left-to-right (Barnett and Corballis 2005; Iwabuchi and Kirk 2009). The reduced asymmetry in women is mainly due to shorter left-to-right IHTT in women than men. Different assumptions have been made to explain this asymmetry in IHTT such as a smaller average size in the right occipital lobe resulting in fewer callosal fibers projecting from left-to-right posterior areas (Saron and Davidson 1989), faster axonal conduction in the right hemisphere relative to the left (Barnett and Corballis 2005), or the degree of hemispheric specialization as suggested by a reversal of asymmetric transfer times for verbal and non-verbal stimuli (Nowicka et al. 1996; Rugg and Beaumont 1978). Alternatively, differences in the distribution of gray and white matter in the two cerebral hemispheres have been proposed to reflect neuronal organization promoting inter-or intrahemispheric processing with more gray matter relative to white matter in the left hemisphere than in the right, particularly in the frontal regions, emphasizing parallel intrahemispheric processing rather than interhemispheric transfer (Gur et al. 1980). Current volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (Pujol et al. 2002) and DTI (Hagmann et al. 2003; Kraus et al. 2007) protocols have reported left–right asymmetries of the superior longitudinal tract, the upper cerebellar peduncle and in frontal and temporal white matter supporting the assumption that anatomical differences between both hemispheres and the proportion of gray and white matter may underlie functional asymmetry.

Parallel Processing, Redundancy Gain and the Corpus Callosum

To explore our visual environment, we integrate visual information from each visual hemifield as it reaches the contralateral cerebral hemisphere. Because of the anatomical arrangement of the human visual system that projects visual inputs from each visual hemifield to the contralateral visual cortex, the independent contributions from each hemisphere and the role of the corpus callosum for the integration of parallel visuomotor processes can be readily assessed by comparing paired with single targets presented to one or both visual hemifields. Typically, responses are faster to stimulus pairs than single stimuli, a phenomenon called the redundant targets effect (RTE), or summation effect (Miller 1986; Mordkoff and Yantis 1991; Roser and Corballis 2003). The RTE is usually tested with brief light flashes presented for less than 150 ms to prevent eye movements that would shift the visual field (Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1995; Miniussi et al. 1998; Iacoboni et al. 2000).

Researchers have proposed two explanations for redundancy gains from paired stimulation, the ‘horse race’ model (Raab 1962) and the ‘co-activation’ model (Miller 1982). If two stimuli, one within each hemisphere, are processed independently or in parallel, the faster processed stimulus ‘wins the race’ (Miller and Ulrich 2003; Raab 1962). Statistically, the probability of eliciting a fast response is twice as high when two stimuli are presented simultaneously than when only one is presented. The probability or ‘race’ model assumes that each stimulus is transmitted along separate channels and the response is triggered as soon as a decision is made by either one of the two channels (Mordkoff and Yantis 1991). An alternative to the ‘race’ model is required to explain the situation when gain from double stimulus presentations exceeds probability (Raab 1962), i.e., an enhanced redundancy gain. Here, co-activation from otherwise independent processing channels may occur to increase signal strength of redundant targets and produce a speeded response (Miller 1982).

Millers’ use of the term co-activation was theoretical and not founded on measured brain activity. Recent studies have associated enhanced redundancy gain (co-activation model) with neural correlates and implied a possible role of the CC (Bucur et al. 2005; Miniussi et al. 1998; Savazzi and Marzi 2002; Schulte et al. 2006a; Turatto et al. 2004), in contrast to the horse race model that assumes two independent processing channels and does not require the corpus callosum. For example, studies on split brain patients and on normal subjects testing redundancy gain for paired targets within the same visual hemifield, i.e., intrahemispheric summation, and in both hemifields, i.e., interhemispheric summation, report larger redundancy gains for paired bilateral than unilateral stimulation (Iacoboni et al. 2000; Marks and Hellige 2003; Ouimet et al. 2009; Pollmann and Zaidel 1998; Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1995; Schulte et al. 2006a) indicating that interhemispheric communication may mediate neural co-activation. However, split-brain and acallosal patients typically show abnormally enhanced bilateral RTEs compared to healthy adults, which implies that other than callosal commissures can mediate interhemispheric processing advantages (Aglioti et al. 1996; Corballis 1998; Corballis et al. 2003; Iacoboni et al. 2000; Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1995; Roser and Corballis 2002, 2003). It has been argued that healthy individual may not benefit as much from a bilateral presentation as do the split-brain individuals because an intact corpus callosum assures fast transfer of information between hemispheres even when only one hemisphere is stimulated directly by visual input, i.e., when a single lateralized stimulus is presented.

But how can enhanced RTEs in the split-brain depend upon convergence of information from separated hemispheres when at the same time prolonged CUDs in split-brain patients reflect slow subcortical transmission? To explicate this paradox in the split-brain, Reuter-Lorenz et al. (1995) proposed in their “and-or model” that the RTE is based on response competition between the cerebral hemispheres that depends on callosal connectivity. According to this model, co-activation occurs at a response selection stage (see also Miller 2004; Roser and Corballis 2003), and acts as an ‘and’ gate that requires input from both hemispheres, while prolonged CUDs in split-brain patients are due to the use of relatively inefficient ipsilateral pathways in making crossed responses. Corballis et al. (2002) assumed that summation is due to cortical projection to a subcortical arousal system that is normally inhibited by the corpus callosum, while in the split-brain patient, interhemispheric inhibition is released, resulting in a paradoxically enhanced redundant targets effect.

Even though the CC is the largest commissure at the cortical level, there are other pathways connecting the hemispheres: the anterior and posterior commissures, and subcortical projections through the hippocampal, habenular, and intercollicular brain systems (Bayard et al. 2004). Activation of the superior colliculi, part of the retino-tectal pathway within the visual brain system, has been associated with the initiation of fast responses (e.g., eye movements: Klier et al. 2003; arm-reaching movements: Dean et al. 1989; and even shifts in attention that do not involve any overt movements: Ignashchenkova et al. 2004). Iacoboni et al. (2000) proposed that the superior colliculi and the posterior callosal area connecting visual extrastriate areas are the key structures for interhemispheric neural co-activation explaining visuomotor integration between hemispheres: Activity in the extrastriate cortex following visual input feeds into the superior colliculi, which then feeds back to extrastriate cortices. In split-brain patients with long interhemispheric transfer times (IHTT) as measured with the CUD, feedback to the superior colliculi would be asynchronous and sum up over time to be larger than in normal subjects with short IHTT and synchronous superior colliculus input. The larger superior colliculus activation would feed a stronger signal back to the extrastriate cortices, which in turn send stronger activation to the premotor cortex, speeding the response. Consistent with his model, Iacoboni et al. (2000) found enhanced RTEs in split-brain patients with long CUDs (> 15 ms) but not in patients with short CUDs (< 15 ms). Further evidence for an involvement of subcortical structures, such as the superior colliculus, or cortico-subcortical interactions (Roser and Corballis 2003) comes from split-brain studies (Corballis 1998; Savazzi and Marzi 2004) demonstrating reduced RTEs with equiluminant stimuli that are invisible to the superior colliculi and thus restrict processing to cortical pathways of the retino-geniculate parvocellular system (Livingstone and Hubel 1987). However, despite converging evidence for a perceptual explanation for the RTE (Corballis et al. 2003; Iacoboni et al. 2000; Miniussi et al. 1998; Murray et al. 2001; Schulte et al. 2006a), others argue that there could also be a premotor explanation (Diederich and Colonius 1987; Giray and Ulrich 1993; Iacoboni and Zaidel 2003; Ouimet et al. 2009).

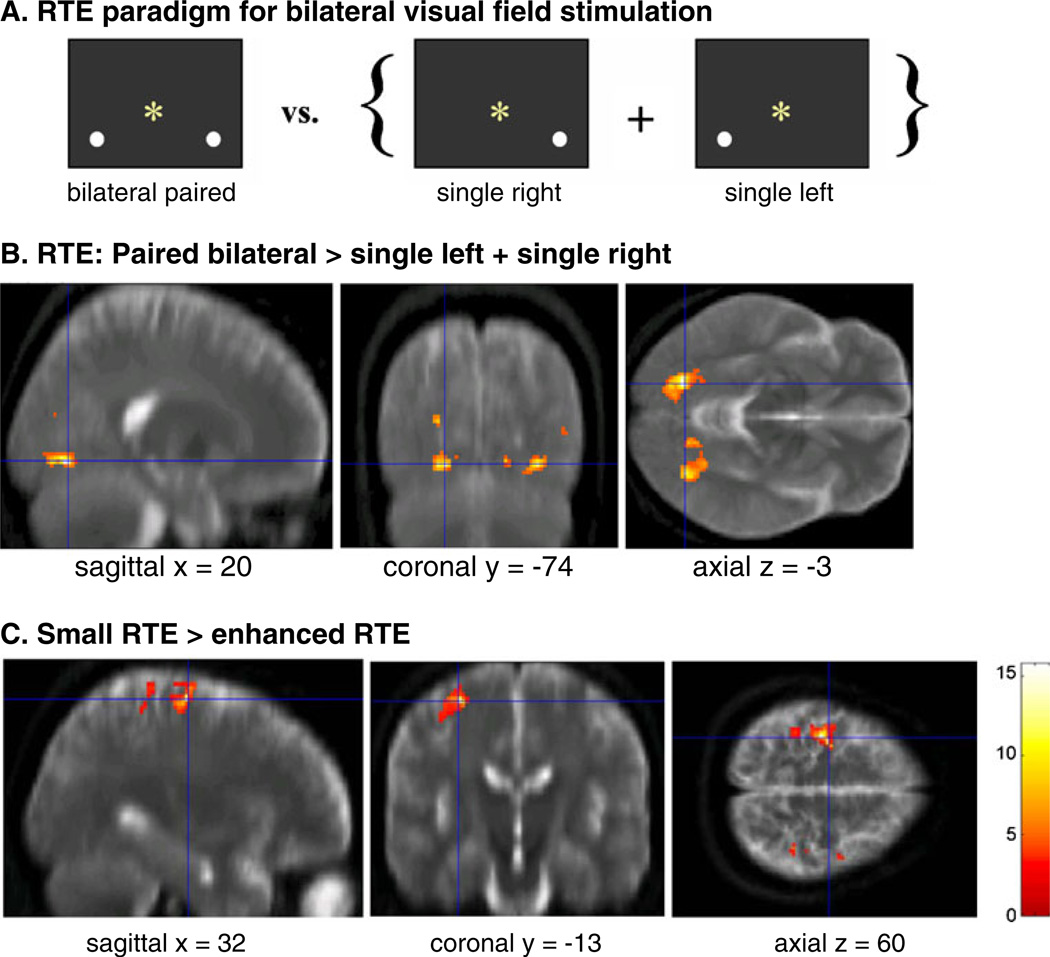

In healthy subjects, considerable inter-subject variability has been observed: approximately half showing enhanced RTEs that violate the ‘race’ model while half do not (Corballis 2002; Schulte et al. 2006a). This normal variability in RTE suggests involvement of different neural loci (extrastriate, premotor or frontal cortical areas) depending on strategy selection, task demands, and stimulus characteristics. In an fMRI study comparing normal individuals with small and enhanced RTEs, we found evidence for both perceptual and premotor/decisional loci for the RTE. Whereas all individuals showed bilateral activation of extrastriate cortices to paired in contrast to summed single stimulus conditions, individuals with small RTEs activated frontal and premotor areas more than those with large RTEs (Schulte et al. 2006a) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Redundant Targets Effect (RTE): a Paradigm illustrating the contrast of interest: bilateral vs. unilateral stimulation. b Activation of bilateral extrastriate areas in the paired>single contrast (SPM2; T=4.30). c Violation of the ‘race’ model predictions: activation of premotor, motor and frontal brain regions in individuals with small RTEs (no violation) compared to those with enhanced RTEs (violation) (SPM2; T=4.03). Modified from Schulte et al. (2006a)

Our analysis was between individuals, whereas that of Mooshagian et al. (2008) compared activation between fast ‘co-activation’ trials and slower ‘not co-activation’ trials within the same healthy subjects. They found right temporo-parietal junction activation for ‘co-activation’ trials, specifically in the angular gyrus. This finding is of particular interest because the temporo-parietal junction has been implicated in spatial attention and, when damaged, in the occurrence of visuo-spatial neglect (Lux et al. 2006; Mort et al. 2003; Müller-Oehring et al. 2007, 2009a; Shirani et al. 2009). A phenomenon closely associated with visuo-spatial neglect is ‘extinction to paired simultaneous stimulation,’ when patients see single visual stimuli, but fail to report contralesional stimuli when an ipsilesional stimulus is presented at the same time. In this case, the contralesional stimulus is extinguished from awareness (Meister et al. 2006; Schendel and Robertson 2002).

In patients with unilateral left extinction after right temporo-parietal damage, enhanced redundancy gains have been observed even when one stimulus in a pair was presented to the left hemifield and therefore was not perceived (Marzi et al. 1996; Müller-Oehring et al. 2009a, b, 2010). We recently found that visual extinction of left-sided stimuli, but not RTE, was correlated with prolonged CUDs in neglect patients with right temporo-parietal lesions (Müller-Oehring et al. 2009a). Thus, despite extinction of left-sided stimuli in paired trials, neglect patients showed unconscious parallel processing of contralesional stimuli (RTE). This was the case even when contralesional visual field input was lacking, as evidenced by additional visual field defects in these patients, or delayed, as evidenced by prolonged CUDs (Müller-Oehring et al. 2009a). Hence, under competitive bilateral stimulus conditions, the delayed contralesional visual field input may not be detected by the intact left hemisphere, which presumably mediates the task given the impairment of the right hemisphere, leading to extinction of this stimulus from the patient’s awareness. This is supported by surprising results from Marzi et al. (1997), who recorded event-related potentials (ERPs) in unilateral brain damaged patients, and found that the ispilesional (commissural) response was lacking or reduced in patients with a right hemisphere lesion but not in patients with a left hemisphere lesion. They speculated that this laterality difference might be related to a left–right asymmetry in callosal projections with callosally projecting neurons being more numerous in the right than the left hemisphere (Marzi et al. 1991). Consequently, they argued, it would be reasonable to assume that unilateral right-hemispheric lesions will cause a greater loss of callosal fibers than similar left-hemispheric lesions. That RTEs after right temporo-parietal damage were not abolished due to reduced or delayed visual input from the contralesional visual hemifield (Marzi et al. 1997; Müller-Oehring et al. 2009a) provides behavioral evidence for a post-perceptual stage of neural co-activation. It further supports the assumption that subcortical interhemispheric pathways play a role in redundancy gain and that cortical interhemispheric pathways mediate visual awareness (Marzi et al. 1997; Silvanto et al. 2009).

In addition, current research indicates that these neural co-activation systems of bilateral sensorimotor integration (as measured by redundancy gain) further depend on cognitive processes engaged by task characteristics (Reinholz and Pollmann 2007), and individual differences in strategy selection (Schulte et al. 2006a). For example, using functional MRI in healthy subjects, Reinholz and Pollmann (2007) studied redundancy gain for higher-level visual identification and categorization processes using combinations of pictures of faces and houses presented simultaneously to both visual hemifields. They observed fusiform face area (FFA) activation for redundant pictures of faces and parahippocampal place areas (PPAs) activation for redundant pictures of buildings suggesting involvement of task-specific higher-order visual object-selective areas in visuomotor integration of redundant information.

Despite the ongoing debate over the cortical locus of co-activation, results from split-brain research clearly demonstrate that interhemispheric integration of simple percepts can occur without the presence of the CC through subcortical transmission of information that is projected to cortical sites in both hemispheres. In the split-brain, enhanced RTEs have been interpreted as an absence of callosal inhibition (Corballis et al. 2002; Zaidel and Iacoboni 2003). Yet, in healthy individuals, a recent study showed greater RTEs for equiluminant than high-contrast stimuli implying cortical rather than subcortical integration mechanisms (Schulte et al. 2004), in contrast to split-brain patients, who typically show reduced RTEs with equiluminant stimuli (Corballis 1998; Roser and Corballis 2002). Furthermore, callosal degradation without disconnection, e.g., in chronic alcoholics (Lim and Helpern 2002; Kubicki et al. 2003; Pfefferbaum and Sullivan 2003) has been found to correlate with reduced RTE with equiluminant stimuli (Schulte et al. 2005). These results imply a cooperative role of the CC and that such cooperation is reduced by subtle degradation of callosal integrity. In addition, data in healthy subjects with an intact CC showed bilateral extrastriate activation for RTEs (Schulte et al. 2006a) (Fig. 2) and temporo-parietal activations for enhanced RTEs (Mooshagian et al. 2008) and support an interhemispheric cooperation model for neural summation. Subtle degradation of callosal structure also occurs in healthy aging (Bartzokis et al. 2004; Bucur et al. 2005; Madden et al. 2009; Sullivan et al. 2001) and can result in disturbed bilateral integration of visual (Müller-Oehring et al. 2007; Schulte et al. 2004, 2005), cognitive (Kennedy and Raz 2009; Zahr et al. 2009), and motor functions (Bartzokis et al. 2008; Sullivan et al. 2006, 2010).

In summary, the role of the corpus callosum for the integration of lower-level visuomotor functions is controversial. While split-brain research indicates that the CC acts in an inhibitory fashion within a subcortico-cortical network (Corballis et al. 2002; Roser and Corballis 2003), recent research on callosal degradation without disconnection suggests that the corpus callosum acts cooperatively. The review of the few studies on interhemispheric communication emanating from the right temporo-parietal junction further suggests a special role of the corpus callosum in conscious perception (Marzi et al. 1991, 1997; Müller-Oehring et al. 2009a). Activation of the right temporo-parietal junction appears to mediate co-activation for visuomotor integration in conjunction with homologous temporo-parietal regions in the contralateral hemisphere (Mooshagian et al. 2008) probably associated with bilateral attentional mechanisms normally equilibrated by reciprocal callosal inhibition (Kinsbourne 1993) supporting conscious perception (Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1995).

The Role of the CC for the Integration of Higher Cognitive Functions

Hemispheric specialization for higher-order cognition such as the left-hemispheric dominance for language and right-hemispheric dominance for visuospatial attention (Damasio and Damasio 1993; Gazzaniga 2005) has been assumed to be a consequence of interhemispheric connectivity, i.e., the likelihood of intrahemispheric processing and hemispheric specialization of brain functions increases with increased time constraints of callosal conduction delay (Hopkins and Rilling 2000). Although the functions of the CC are more associated with transferring sensory information and visuomotor integration (Banich 1998) recent studies highlight the pivotal role of CC for higher-order cognitive functions such as identification of complex stimuli (Banich et al. 2000; Schulte et al. 2006b; Skiba et al. 2000). Studying neuropsychiatric diseases, such as alcoholism, that are marked by subtle white matter neuropathology, particularly of the CC (Harper and Kril 1988, 1990; Harper and Matsumoto 2005; Pfefferbaum and Sullivan 2002, 2005; Pfefferbaum et al. 2006; Tarnowska-Dziduszko et al. 1995), provides a window of opportunity to investigate the contribution of CC degeneration to the functional integration of information across the hemispheres to perform complex tasks (Hiatt and Newman 2007).

It has been assumed that both hemispheres interact with each other in a dynamic push-pull fashion to equalize the direction of visuospatial attention (Kinsbourne 1977, Kinsbourne and Bruce 1987; Reuter-Lorenz et al. 1990; Corbetta et al. 2005). In this activation-orienting model it is postulated that visuospatial attention is biased in the direction contralateral to the more activated hemisphere (Schulte et al. 2001). Based on the assumption that dynamic interactions between the hemispheres via the CC affect attentional processing (Banich 1998), we recently tested whether the integrity of the CC in alcoholics predicts the functioning of neural systems known to underlie higher-order component processes of selective attention and conflict processing. To identify the role of hemispheric lateralization and interhemispheric transfer within the fronto-parietal attention system, we developed a lateralized Stroop paradigm (Schulte et al. 2006b). For nearly 75 years, the Stroop color-word effect has provided a rich paradigm for parsing and manipulating processes of attention and conflict in the context of stimuli naturally compelling because of their semantic content (Stroop 1935; MacLeod 1991). Processing words at their semantic level is involuntary and automatic and naturally overrides perceptual tags, such as the color of the ink of a written word that has no intrinsic value (Carter et al. 2000; MacDonald et al. 2000; Schulte et al. 2009). The Stroop effect can be conceptually considered as a left hemisphere lateralized task with greater interference arising from the semantic content of the word (MacLeod 1991). Because of its preferentially processing of verbal information (e.g., language, speech, and writing), the left hemisphere should be more affected than the right by semantic competition (Luo et al. 1999). This laterality effect was demonstrated in a study (Weekes and Zaidel 1996), which used separate color words and color patches and found greater Stroop interference when color words were presented to the left than right hemisphere independent of the location of the color patch (i.e., within the same hemifield or in the opposite hemifield).

In our lateralized Stroop match-to-sample task, we analyzed hemispheric preference for Stroop word-color information by comparing reaction times to right visual field trials (preferred left cerebral hemisphere for word processing) with reaction times to left visual field trials (non-preferred right hemisphere). We found that control subjects and patients with chronic alcoholism differed in performance as a function of lateralized stimulus presentations and attentional processes when color cues matched or did not match the word’s color (Schulte et al. 2006b): For matching colors, both groups showed a right visual field advantage; for nonmatching colors, however, controls showed a left visual field advantage, whereas alcoholics showed no visual field advantage. We speculated that controls were more successful than alcoholics in disengaging their attention from the invalidly cued color to correctly process the color of the Stroop stimulus in nonmatch color trials. Subsequent disengagement and shift of attention away from the invalidly cued color to the correct target color of the Stroop stimulus is associated with right-hemisphere functions (Blumstein and Cooper 1974; Christman 2001; Hartje et al. 1985; Posner 1980) and may be responsible for the left visual field advantage in nonmatch trials observed in healthy controls. This left visual field advantage in nonmatch trials was correlated with a larger callosal splenium area in controls but not alcoholics indicating that information presented to the non-preferred hemisphere is transmitted via the splenium to the hemisphere that is specialized for efficient processing. This processing route for visual hemifield information was disrupted in alcoholics, possibly as a result of callosal thinning.

Furthermore, our visual world can be decomposed into component features and then integrated into more complex stimuli, objects and scenes—a concept originated from investigations of the visual cortex (Felleman et al. 1997; Pandya and Sanides 1973). Thus, whole-part perception is based on the extraction of higher-order or global features (such as the silhouette of a face, or street scene) and details on the local level (e.g., facial details like eyes and nose, or details in a street scene like cars and traffic lights). A widely used paradigm to study whole-part perception is a target detection task that uses hierarchical letters, where a large (global) letter is made of smaller (local) letters, modeling the hierarchical structure of visual world scenes (Fink et al. 1997; Navon 1977).

Current models of local-global perception assume that local and global processes proceed in parallel, with a left hemisphere advantage in processing local features and a right hemisphere advantage in processing the global “gestalt”, as indicated by brain lesion studies (Delis et al. 1986, 1988; Lamb et al. 1989; Robertson et al. 1988, 1991; Yamaguchi et al. 2000) and neuroimaging studies in healthy subjects (Evans et al. 2000; Fink et al. 1996, 1999; Han et al. 2002; Heinze et al. 1998; Weber et al. 2000; Yamaguchi et al. 2000). Thus, the study of local-global perception may contribute to our understanding of the role of the CC for higher-order visual integration.

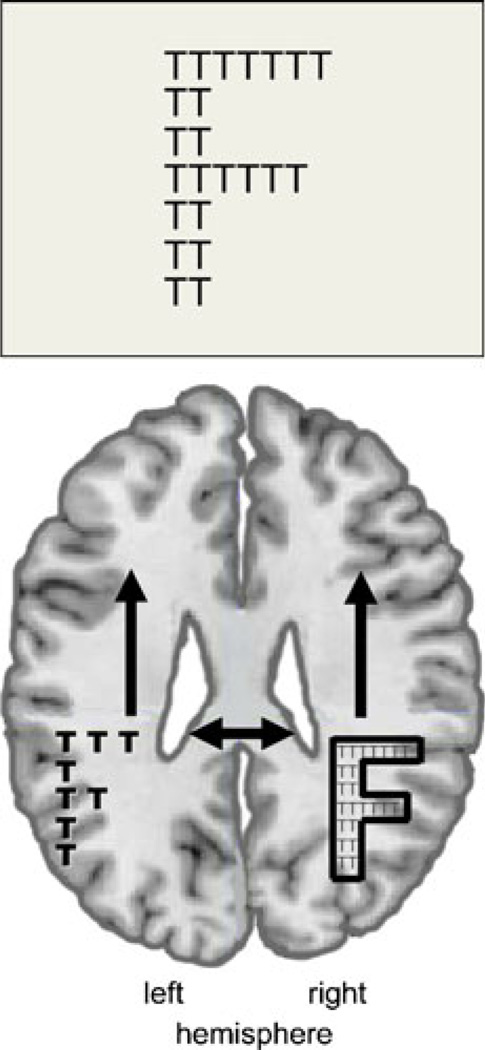

Although RT studies using lateralized hemifield presentations have not always shown local-global hemispheric differences (Blanca et al. 1994; Evert and Kmen 2003; Hübner 1997; Yovel et al. 2001), electrophysiological studies using central stimulus presentations do support this hemispheric processing bias for left-local and right-global information (Heinze and Münte 1993; Heinze et al. 1998; Malinowski et al. 2002; Yamaguchi et al. 2000). Together, these studies suggest that, in principle, each hemisphere can process local and global information; however, hemispheric processing advantages emerge when local and global information is processed simultaneously in both hemispheres. The competition hypothesis (Han et al. 2002; Volberg and Hübner 2004) proposes that with central stimulation both hemispheres have simultaneous access to the same visual information and the specialized hemisphere assigns more resources to a given local or global target level bringing hemispheric differences for local and global feature processing to light (Fig. 3). With lateralized presentations, the hemisphere contralateral to the stimulated hemifield receives the visual information prior to the ipsilateral hemisphere that receives information after interhemispheric transfer through the CC. The resulting time difference in processing between hemispheres may eliminate interhemispheric competition, and also hemispheric differences associated with local and global feature processing. Results from an ERP study (Han et al. 2002) that found hemispheric differences only for centrally presented hierarchical stimuli and not for lateralized stimulus presentations, are consistent with the competition hypothesis.

Fig. 3.

Model of whole-part perception: Parallel intrahemispheric and transcallosal interhemispheric processing of local and global features. With central stimulation, the specialized hemisphere assigns more resources to a given local or global target level promoting hemispheric differences with global features (e.g., big letter F) preferentially processed in the right cerebral hemisphere and local features (e.g., small letters T) in the left hemisphere (competition hypothesis)

Local-global paradigms have yielded two measures: (a) the difference in response times to local and global targets, or precedence effect, which indexes parallel local and global processes assuming independent processing channels for local and global features, and (b) the difference in response times to incongruent (e.g., a global F made up of local Ts) and congruent stimuli (e.g., a global T made up of local Ts), or interference effect, which indexes local-global inhibition in situations of competition. Several studies indicate a global-over-local precedence effect, i.e., faster responses to global than local features, and global interference, i.e., slower responses when the global feature was incongruent than when it was congruent with the local feature (Navon 1977). However, local precedence and local interference have also been reported (Müller-Oehring et al. 2007). Which level—local or global—is processed faster depends on stimulus size (Kinchla and Wolfe 1979), the size ratio between global and local forms (Kimchi and Palmer 1982), the stimulus’ location in the visual field (central or peripheral) (Kimchi 1992; Lamb and Robertson 1987, 1988), and attentional selection (Broadbent 1977; Han et al. 2001; Pomerantz 1983; Robertson et al. 1993; Weissman et al. 2005; Yamaguchi et al. 2000).

Up to date, only a few studies have investigated the role of the CC in local-global precedence and interference. In 1993, Robertson et al. found that split-brain patients did not show global interference despite normal global precedence. However, Weekes et al. (1997) repeated the experiment in two of the same split-brain patients and found both preserved global precedence and global interference. Thus, in contrast to Robertson et al. (1993), their findings imply that the CC is not necessary for eliciting global interference. Rather, because each hemisphere can process local and global information, interference effects occur within one hemisphere in the absence of the CC. The different results from these two studies may be due to slight differences in stimulus characteristics and presentation: Robertson et al. (1993) used stimulus eccentricities of 2.7° while Weekes et al. (1997) used stimulus eccentricities of 1° for each visual hemifield. Given that there is a 1–2° stripe overlap at the retinal vertical meridian between the two visual hemifields, the smaller stimulus eccentricity and enhanced stimulus-background contrast used by Weekes et al. (1997) may have in fact sent information to the left and right visual cortices and contributed to intrahemispheric local-global competition. Thus neither study provides clear evidence for callosal involvement in local-global interference.

Our own recent studies in normal aging (Müller-Oehring et al. 2007), alcoholism (Müller-Oehring et al. 2009b), and HIV infection (Müller-Oehring et al. 2010), all conditions with callosal thinning or impaired integrity, provide new evidence for CC involvement in local-global processing. In healthy aging, for example, we found that larger local precedence effects and greater local interference correlated with smaller callosal genu area (Müller-Oehring et al. 2007). In addition to precedence and interference, we also tested the relation between the CC and local-global facilitation. Local-global facilitation effects have been found previously for attentional cueing (Lamb and Yund 2000; Robertson et al. 1993), and repetitive priming (Han et al. 2003; Schatz and Erlandson 2003). We found, that in healthy subjects posterior callosal splenium area was associated with local-global facilitation from repetition priming independent of age (Müller-Oehring et al. 2007). Converging evidence for a differentiated role of the CC in local-global integration comes from two recent DTI studies on chronic alcoholism (Müller-Oehring et al. 2009b) and HIV-infection (Müller-Oehring et al. 2010) indicating that local-global interference is mediated by anterior callosal genu integrity and local-global facilitation by posterior callosal splenium integrity.

Together, these findings suggest that the CC mediates lateralized higher-order cognition such as whole-part perceptual integration. Specifically, anterior callosal integrity appears to mediate local-global interference (callosal inhibition), whereas posterior callosal integrity seems to mediate local-global facilitation (callosal cooperation). Thus, component processes of visuospatial perception and attention are attributable, at least in part, to the integrity of callosal pathways, relevant for the integration of lateralized brain functions.

Conclusion

Geschwind (1965) formulated the idea that many neurological disorders can be understood as ‘disconnections syndromes’ in which white matter damage degrades network functions leading to specific cognitive disabilities such as visuospatial neglect (Doricchi et al. 2008). Numerous studies have since contributed to our current understanding of interhemispheric sharing of information from early visual input to complex decision-making. Many of these studies have focused on split-brain patients whose cerebral commissures had been surgically disconnected to improve intractable epilepsy (for reviews see Gazzaniga 2000, 2005; Lassonde and Ouimet 2010). The recent advance of neuroimaging techniques such as DTI and fMRI have provided the opportunity to study CC function in situations of callosal degradation without disconnection. These studies have documented a central role of the CC for interhemispheric visuomotor integration and for higher-order cognitive functions, and have shown that even subtle degradation of the CC in neurologically impaired patients can be related to deficits in the transfer of information between the hemispheres. For visuomotor integration, split-brain research suggests that the CC exerts an inhibitory function on the hemispheres and that absence of callosal inhibition results in enhanced bilateral processing advantages. Recent DTI and fMRI studies that tested bihemispheric visuomotor integration in the connected brain, however, provide evidence for callosal cooperation. Whether the specific role of the CC for visuomotor integration is inhibitory or cooperative remains unclear. At this point, it appears plausible to assume that callosal inhibition and cooperation are not mutually exclusive but depend on complex interactions within a subcortico-cortical network that probably equilibrate hemispheric activation according to task demands.

A further aim of this review was to focus on the role of the CC for higher-order lateralized cognitive functions. Together, the reviewed research provides clear indication that the CC contributes to the integration of perception and action, promoting a unified experience of the way we perceive the visual world and prepare our actions. Of particular interest is emerging evidence from neuroimaging that the CC employs a differentiated role with callosal areas transmitting different types of information depending on the cortical destination of connecting fibers. Studies on patients with callosal degradation indicated that anterior callosal fibers linking frontal and premotor areas of the two hemispheres were associated with inhibitory functions in situations of semantic competition (Stroop) and local-global interference, whereas posterior callosal areas connecting temporo-parietal and occipital cortical regions were related with facilitation from redundant targets and local-global features. Thus, to achieve an interhemispheric balance between component brain functions, the CC appears to exert both functional inhibition and excitation (Bloom and Hynd 2005).

Future directions should include new imaging techniques such as fiber tractography in combination with functional neuroimaging and electrophysiological methods to explore the specific role of regional callosal connectivity for brain functions in the healthy brain and callosal degradation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret J. Rosenbloom for comments on the manuscript. Preparation of this article was supported by National Institutes of Health research grants: AA018022, AA010723, AA005965, AA012388, AA017168, AA017432

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors declare that no conflicts of interest are associated with the preparation of this article.

Contributor Information

Tilman Schulte, Email: tilman.schulte@sri.com, SRI International, Neuroscience Program, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493, USA.

Eva M. Müller-Oehring, SRI International, Neuroscience Program, 333 Ravenswood Avenue, Menlo Park, CA 94025-3493, USA Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

References

- Aboitiz F, Scheibel AB, Fisher RS, Zaidel E. Individual differences in brain asymmetries and fiber composition in the human corpus callosum. Brain Research. 1992;598:154–161. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90179-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aglioti S, Smania N, Manfredi M, Berlucchi G. Disownership of left hand and objects related to it in a patient with right brain damage. Neuroreport. 1996;20:293–296. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aralasmak A, Ulmer JL, Kocak M, Salvan CV, Hillis AE, Yousem DM. Association, commissural, and projection pathways and their functional deficit reported in literature. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 2006;30:695–715. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000226397.43235.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz-Zadeh L, Koski L, Zaidel E, Mazziotta J, Iacoboni M. Lateralization of the human mirror neuron system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:2964–2970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2921-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird AE, Warach S. Magnetic resonance imaging of acute stroke. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 1998;18:583–609. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199806000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT. Interhemispheric processing: Theoretical and empirical considerations. In: Davidson R, Hugdahl K, editors. Brain asymmetry. Cambridge: MIT; 1995. pp. 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT. The missing link: the role of interhemispheric interaction in attentional processing. Brain and Cognition. 1998;36:128–157. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1997.0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT, Belger A. Interhemispheric interaction: how do the hemispheres divide and conquer a task? Cortex. 1990;26:77–94. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT, Shenker J. Investigations of interhemispheric processing: methodological considerations. Neuropsychology. 1994;8:263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Banich MT, Milham MP, Atchley R, Cohen NJ, Webb A, Wszalek T, et al. fMRI studies of Stroop tasks reveal unique roles of anterior and posterior brain systems in attentional selection. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12:988–1000. doi: 10.1162/08989290051137521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett KJ, Corballis MC. Speeded right-to-left information transfer: the result of speeded transmission in right-hemisphere axons? Neuroscience Letters. 2005;380:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Sultzer D, Lu PH, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J, Cummings JL. Heterogeneous age-related breakdown of white matter structural integrity: implications for cortical “disconnection” in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Tingus K, Mendez MF, Richard A, Peters DG, et al. Lifespan trajectory of myelin integrity and maximum motor speed. Neurobiology of Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.015. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashore TR. Vocal and manual reaction time estimates of interhemispheric transmission time. Psychology Bulletin. 1981;89:352–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battelli L, Cavanagh P, Martini P, Barton JJ. Bilateral deficits of transient visual attention in right parietal patients. Brain. 2003;126:2164–2174. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer RM. Visual hypoemotionality as a symptom of visual-limbic disconnection in man. Archives of Neurology. 1982;39:702–708. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510230028009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayard S, Gosselin N, Robert M, Lassonde M. Inter-and intra-hemispheric processing of visual event-related potentials in the absence of the corpus callosum. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:401–414. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlucchi G, Heron W, Hyman R, Rizzolatti G, Umilta C. Simple reaction times of ipsilateral and contralateral hand to lateralized visual stimuli. Brain. 1971;94:419–430. doi: 10.1093/brain/94.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlucchi G, Aglioti S, Marzi CA, Tassinari G. Corpus callosum and simple visuomotor integration. Neuropsychologia. 1995;33:923–936. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00031-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanca MJ, Zalabardo C, Garcia-Criado F, Siles R. Hemispheric differences in global and local processing dependent on exposure duration. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JS, Hynd GW. The role of the corpus callosum in interhemispheric transfer of information: excitation or inhibition? Neuropsychology Review. 2005;15:59–71. doi: 10.1007/s11065-005-6252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein S, Cooper WE. Hemispheric processing of intonation contours. Cortex. 1974;10:146–158. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(74)80005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun CM, Daigneault S, Dufresne A, Miljours S, Collin I. Does so-called interhemispheric transfer time depend on attention? American Journal of Psychology. 1995;108:527–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent DE. The hidden preattentive process. American Psychologist. 1977;32:109–118. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.32.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucur B, Madden DJ, Allen PA. Age-related differences in the processing of redundant visual dimensions. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:435–446. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti R, Ghaziri H, Galuske R, Hof PR, Innocenti GM. Evolution amplified processing with temporally dispersed slow neuronal connectivity in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19551–19556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907655106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, MacDonald AM, Botvinick M, Ross LL, Stenger VA, Noll D, et al. Parsing executive processes: strategic vs. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:1944–1948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani M, ffytche DH. The rises and falls of disconnection syndromes. Brain. 2005;128:2224–2239. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarello C, Maxfield L. Varieties of interhemispheric inhibition, or how to keep a good hemisphere down. Brain and Cognition. 1996;30:81–108. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman SD. Individual differences in stroop and local-global processing: a possible role of interhemispheric interaction. Brain and Cognition. 2001;45:97–118. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2000.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JM, Zaidel E. Simple reaction times to lateralized light flashes. Varieties of interhemispheric communication routes. Brain. 1989;112:849–870. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JM, Zaidel E. Anatomical-behavioral relationships: corpus callosum morphometry and hemispheric specialization. Behavioural Brain Research. 1994;64:185–202. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook ND. Callosal inhibition: the key to the brain code. Behavioral Science. 1984;29:98–110. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830290203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC. Interhemispheric neural summation in the absence of the corpus callosum. Brain. 1998;121:1795–1807. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.9.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC. Hemispheric interactions in simple reaction time. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC, Hamm JP, Barnett KJ, Corballis PM. Paradoxical interhemispheric summation in the split brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:1151–1157. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC, Corballis PM, Fabri M. Redundancy gain in simple reaction time following partial and complete callosotomy. Neuropsychologia. 2003;42:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Shulman GL, Miezin FM, Petersen SE. Superior parietal cortex activation during spatial attention shifts and visual feature conjunction. Science. 1995;270:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Tansy AP, Stanley CM, Astafiev SV, Snyder AZ, Shulman GL. A functional MRI study of preparatory signals for spatial location and objects. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:2041–2056. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creem-Regehr SH. Sensory-motor and cognitive functions of the human posterior parietal cortex involved in manual actions. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;91:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR, Damasio H. Brain and language, In “Mind and Brain”, a Scientific American Book. New York: Freeman; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Doricchi F, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Tomaiuolo F, Bartolomeo P. White matter (dis)connections and gray matter (dys) functions in visual neglect: gaining insights into the brain networks of spatial awareness. Cortex. 2008;44:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean P, Redgrave P, Westby GW. Event or emergency? Two response systems in the mammalian superior colliculus. Trends in Neurosciences. 1989;12:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Robertson LC, Efron R. Hemispheric specialization of memory for visual hierarchical stimuli. Neuropsychologia. 1986;24:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(86)90053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kiefner M, Fridlund AJ. Visuospatial dysfunction following unilateral brain damage: dissociations in hierarchical and hemispatial analysis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1988;10:421–431. doi: 10.1080/01688638808408250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich A, Colonius H. Intersensory facilitation in the motor component? A reaction time analysis. Psychological Research. 1987;49:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Doricchi F, Tomaiuolo F. The anatomy of neglect without hemianopia: a key role for parietal-frontal disconnection? Neuroreport. 2003;14:2239–2243. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312020-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doron KW, Gazzaniga MS. Neuroimaging techniques offer new perspectives on callosal transfer and interhemispheric communication. Cortex. 2008;44:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffau H, Capelle L, Sichez N, Denvil D, Lopes M, Sichez JP, et al. Intraoperative mapping of the subcortical language pathways using direct stimulations. An anatomo-functional study. Brain. 2002;125:199–214. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, Kushch A, Gross-Glenn K, Barker WW, Jallad B, Pascal S, et al. Neuroanatomic differences between dyslexic and normal readers on magnetic resonance imaging scans. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48:410–416. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530160078018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MA, Shedden JM, Hevenor SJ, Hahn MC. The effect of variability of unattended information on global and local processing: evidence for lateralization at early stages of processing. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:225–239. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evert DL, Kmen M. Hemispheric asymmetries for global and local processing as a function of stimulus exposure duration. Brain and Cognition. 2003;51:115–142. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(02)00528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabri M, Polonara G, Del Pesce M, Quattrini A, Salvolini U, Manzoni T. Posterior corpus callosum and interhemispheric transfer of somatosensory information: an fMRI and neuropsychological study of a partially callosotomized patient. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2001;13:1071–1079. doi: 10.1162/089892901753294365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Burkhalter A, Van Essen DC. Cortical connections of areas V3 and VP of macaque monkey extrastriate visual cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;379:21–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970303)379:1<21::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich R, Hutsler JJ, Gazzaniga MS. Visual and tactile interhemispheric transfer compared with the method of Poffenberger. Experimental Brain Research. 2004;158:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GR, Halligan PW, Marshall JC, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ, Dolan RJ. Where in the brain does visual attention select the forest and the trees? Nature. 1996;382:626–628. doi: 10.1038/382626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GR, Halligan PW, Marshall JC, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS, Dolan RJ. Neural mechanisms involved in the processing of global and local aspects of hierarchically organized visual stimuli. Brain. 1997;120:1779–1791. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.10.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GR, Marshall JC, Halligan PW, Dolan RJ. Hemispheric asymmetries in global/local processing are modulated by perceptual salience. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster B, Corballis MC. Interhemispheric transmission times in the presence and absence of the forebrain commissures: effects of luminance and equiluminance. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:925–934. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster B, Corballis MC. Interhemispheric transfer of colour and shape information in the presence and absence of the corpus callosum. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:32–45. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Geschwind N. The human language areas and cerebral asymmetries. Revue Medicale de la Suisse Romande. 1980;100:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS. Cerebral specialization and interhemispheric communication: does the corpus callosum enable the human condition? Brain. 2000;123:1293–1326. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.7.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS. Forty-five years of split-brain research and still going strong. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:653–659. doi: 10.1038/nrn1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I. Brain. 1965;88:237–294. doi: 10.1093/brain/88.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giray M, Ulrich R. Motor coactivation revealed by response force in divided and focused attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1993;19:1278–1291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.19.6.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Packer IK, Hungerbuhler JP, Reivich M, Obrist WD, Amarnek WS, et al. Differences in the distribution of gray and white matter in human cerebral hemispheres. Science. 1980;207:1226–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.7355287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib M. Visual hypoemotionality and prosopagnosia associated with right temporal lobe isolation. Neuropsychologia. 1986;24:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(86)90101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann P, Thiran JP, Jonasson L, Vandergheynst P, Clarke S, Maeder P, et al. DTI mapping of human brain connectivity: statistical fibre tracking and virtual dissection. Neuroimage. 2003;19:545–554. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, He X, Yund EW, Woods DL. Attentional selection in the processing of hierarchical patterns: an ERP study. Biological Psychology. 2001;5:31–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Weaver JA, Murray SO, Kang X, Yund EW, Woods DL. Hemispheric asymmetry in global/local processing: effects of stimulus position and spatial frequency. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1290–1299. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Yund EW, Woods DL. An ERP study of the global precedence effect: the role of spatial frequency. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114:1850–1865. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanajima R, Ugawa Y, Machii K, Mochizuki H, Terao Y, Enomoto H, et al. Interhemispheric facilitation of the hand motor area in humans. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:849–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0849h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CG, Kril JJ. Corpus callosal thickness in alcoholics. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:577–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb02577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CG, Kril JJ. Neuropathology of alcoholism. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1990;25:207–216. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C, Matsumoto I. Ethanol and brain damage. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2005;5:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartje W, Willmes K, Weniger D. Is there parallel and independent hemispheric processing of intonational and phonetic components of dichotic speech stimuli? Brain and Language. 1985;24:83–99. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(85)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze HJ, Münte TF. Electrophysiological correlates of hierarchical stimulus processing: dissociation between onset and later stages of global and local target processing. Neuropsychologia. 1993;31:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(93)90132-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze HJ, Hinrichs H, Scholz M, Burchert W, Mangun GR. Neural mechanisms of global and local processing. A combined PET and ERP study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:485–498. doi: 10.1162/089892998562898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Newman JP. Behavioral evidence of prolonged interhemispheric transfer time among psychopathic offenders. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:313–318. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S, Frahm J. Topography of the human corpus callosum revisited-comprehensive fiber tractography using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2006;32:989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Rilling JK. A comparative MRI study of the relationship between neuroanatomical asymmetry and interhemispheric connectivity in primates: implication for the evolution of functional asymmetries. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2000;114:739–748. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.4.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner R. The effect of spatial frequency on global precedence and hemispheric differences. Perception & Psychophysics. 1997;59:187–201. doi: 10.3758/bf03211888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugdahl K, Davidson RJ. The asymmetrical brain. Cambridge: MIT; 2003. pp. 259–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hutner N, Oscar-Berman M. Visual laterality patterns for the perception of emotional words in alcoholic and aging individuals. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:144–154. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Zaidel E. Channels of the corpus callosum. Evidence from simple reaction times to lateralized flashes in the normal and the split brain. Brain. 1995;118:779–788. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Zaidel E. Interhemispheric visuo-motor integration in humans: the effect of redundant targets. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;17:1981–1986. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Zaidel E. Interhemispheric visuo-motor integration in humans: the role of the superior parietal cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Ptito A, Weekes NY, Zaidel E. Parallel visuomotor processing in the split brain: cortico-subcortical interactions. Brain. 2000;123:759–769. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.4.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignashchenkova A, Dicke PW, Haarmeier T, Their P. Neuron-specific contribution of the superior colliculus to overt and covert shifts of attention. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nn1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti GM. Postnatal development of corticocortical connections. Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences, Suppl. 1986;5:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti GM. Exuberant development of connections, and its possible permissive role in cortical evolution. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93936-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabuchi SJ, Kirk IJ. Atypical interhemispheric communication in left-handed individuals. Neuroreport. 2009;20:166–169. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32831f1cbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancke L, Steinmetz H. Interhemispheric transfer time and corpus callosum size. Neuroreport. 1994;5:2385–2388. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199411000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeeves MA, Moes P. Interhemispheric transfer time differences related to aging and gender. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:627–636. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keary CJ, Minshew NJ, Bansal R, Goradia D, Fedorov S, Keshavan MS, et al. Corpus callosum volume and neurocognition in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:834–841. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0689-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Raz N. Aging white matter and cognition: differential effects of regional variations in diffusion properties on memory, executive functions, and speed. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:916–927. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi R. Primacy of wholistic processing and global/local paradigm: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:24–38. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi R, Palmer SE. Form and texture in hierarchically constructed patterns. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1982;8:521–535. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.8.4.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchla RA, Wolfe JM. The order of visual processing: “Top–down,” “bottom–up”, or “middle–out”. Perception & Psychophysics. 1979;25:225–231. doi: 10.3758/bf03202991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M. Hemi-neglect and hemisphere rivalry. Advances in Neurology. 1977;18:41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M. The corpus callosum equilibrates hemispheric activation. In: Zaidel E, Iacoboni M, editors. The parallel brain: The cognitive neuroscience of the corpus callosum. Cambridge: MIT; 2003. pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M, Hicks RB. Functional cerebral space: A model for overflow, transfer and interference effects in human performance: A tutorial review. In: Requin J, editor. Attention and performance VII. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M. Orientational bias model of unilateral neglect: Evidence from attentional gradients within hemispace. In: Marshall IH, Robertson JC, editors. Unilateral neglect: Clinical and experimental studies. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsbourne M, Bruce R. Shift in visual laterality within blocks of trials. ACTA Psychologica (Amsterdam) 1987;66:139–155. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(87)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier EM, Wang H, Crawford JD. Three-dimensional eye-head coordination is implemented downstream from the superior colliculus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89:2839–2853. doi: 10.1152/jn.00763.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MF, Susmaras T, Caughlin BP, Walker CJ, Sweeney JA, Little DM. White matter integrity and cognition in chronic traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Brain. 2007;130:2508–2519. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, Westin CF, Nestor PG, Wible CG, Frumin M, Maier SE, et al. Cingulate fasciculus integrity disruption in schizophrenia: a magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]