Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable, B-cell malignancy, characterized by the clonal proliferation and accumulation of malignant plasma cells in bone marrow. Despite recent advances in understanding of genomic aberrations, a comprehensive catalogue of clinically actionable mutations in MM is just beginning to emerge. The tyrosine kinase (TK) and RAS oncogenes, which encode important regulators of various signaling pathways, are among the most frequently altered gene families in cancer. To clarify the role of TK and RAS genes in pathogenesis of MM, we performed a systematic, targeted screening of mutations on prioritized RAS and TK genes, in CD138 sorted bone marrow specimens from 42 untreated patients. We identified a total of 24 mutations in KRAS, PIK3CA, INSR, LTK and MERTK genes. In particular, seven novel mutations in addition to known KRAS mutations were observed. Prediction analysis tools, PolyPhen and SIFT were used to assess the functional significance of these novel mutations. Our analysis predicted that these mutations may have a deleterious effect, resulting in functional alteration of proteins involved in the pathogenesis of myeloma. While further investigation is needed to determine the functional consequences of these proteins, mutational testing of the RAS and TK genes in larger myeloma cohorts might be also useful to establish the recurrent nature of these mutations.

Keywords: Multiple Myeloma, Tyrosine Kinase, RAS, Resequencing, Mutation analysis, Cancer

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematopoietic malignancy, characterized by uncontrolled accumulation of plasma cells in the bone marrow [1]. Despite advances in systemic and supportive therapies, MM remains a fatal disease. Mutations in receptor tyrosine kinase (TK) and RAS oncogene gene families resulting in constitutive activation of the gene product have been reported in myeloma [2-6]. However, a recent mutational screening of 31, receptor TK gene domains revealed few disruptive mutations in MM [2]. Furthermore, mutational studies in RAS pathway genes, have described conflicting results in terms of their existence and frequency in MM [3, 5-9].

Emerging technologies such as genome-wide screening of mutations have been used in several cancers including myeloma [2, 10] and numerous somatic mutations in many genes have been identified and catalogued. It is worth noting that the distributions of mutations have differed in each of these cancer types and in individual samples [11]. Very recently, whole genome sequence and exome analyses in myeloma patients reported numerous putative mutations in a large number of genes [12]. Although this powerful technology shows great promise, its application to routine clinical or research practice is not viable considering the time and cost involved. Using a targeted resequencing approach, we performed a systematic and focused profiling of the more commonly involved candidate tyrosine kinase and RAS oncogenes in a large panel of myeloma patients. Our objective was to identify mutations that could reveal a genetic signature for MM and further our understanding of molecular events and potentially identify novel therapeutic targets.

Methods

DNA for resequencing analysis was extracted from CD138 selected bone marrow cells using AutoMacs (Miltenyi Biotec, CA). The study cohort consisting of 42 newly diagnosed, untreated, MM patients was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine. Informed consent from the patients was obtained in accordance to the declaration of Helsinki.

Expression data from GEO accession GSE755 [13] was used to generate a heat map (s.Figure 1a-d) as a way of prioritizing the RTK and RAS pathways genes. The GEO data set, consisting of 173 MM samples with and without skeletal lesions as diagnosed by MRI, was analyzed by two different methods: (1) Function Express, an annotation-based microarray analysis [http://cbmi.wustl.edu/html/FEClient.html] and (2) Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software (Affymetrix Inc, Santa Clara, CA). The Affymetrix data was generated using a baseline correction of 1500 to generate absence/presence calls.

Based on the top hit expression profiles and the availability of previously established primer and sequencing conditions, we prioritized these candidate genes for analyses using the standard resequencing pipeline implemented at the Genome Institute (GI) at Washington University Medical School [http://genome.wustl.edu/] [14, 15]. Gene sequences from GenBank [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov] and Ensembl [www.ensembl.org] were used as reference for assembly and primer construction. The primers were either designed by ABI VariantSEQr [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/probe/doc/ProjVariantSEQr.shtml] or with Primer 3 [http://primer3.sourceforge.net] based algorithms. Exonuclease/SAP purified amplicons were directly sequenced using BigDye Terminator chemistry on an ABI3730XL automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Mutations were detected using two separate automated detection methodologies: (1) Mutation profiling pipeline [http://cbmi.wustl.edu/html/index.html] and the PolyScan informatics suite (http://genome.wustl.edu/software/polyscan) [16]; Mutations from the resequencing pipeline were viewed in a graphical user interface using Mutation Viewer [http://cbmi.wustl.edu/html/Mutation_Viwer.html]. This allowed us to validate mutations called independently by the two automated calling methodologies.

PolyPhen (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml) and SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/index.html) prediction tools were further used to assess the functional impact of the observed mutations. In addition, we performed a sensitivity test of mutation detection technology by serially diluting and mixing the mutant to wild type allele in a varying range of 0 – 100 %. The G12D mutation of NRAS gene from H929 line was differentially mixed with wild type allele in U266 cell line and sequenced with ABI 3730XL automated sequencer using standard procedures. Student's t-Test was employed to find the significance of the genotype frequencies.

Results

We identified 24 mutations, of which 7 were novel in our cohort (Table 1 and Figure 1). To establish the sensitivity of detection, we performed serial dilution and mixing experiments using a known mutant allele (NRAS-G12D) from the H929 cell line to the normal allele of U266 cell line. Spectral difference of mutant allele was observed when at least 10-20% of cells harbored the mutant allele (s.figure 2). Lack of germline DNA availability limited us from characterizing the somatic events of the observed mutations.

Table I.

DNA alterations in candidate Ras and TK genes in multiple myeloma

| Gene | Gene IDa | Nucleotide changeb | Amino acid change | Zygosityc | dbSNP Id | Minor allele Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRAS2 | 3845 | c.35 G>A | p.G12D | Hetero | ||

| KRAS2 | 3845 | c.34 G>T, c.33 T>C | p.G12C, A11A | Hetero | ||

| KRAS2 | 3845 | c.183 A>C | p.Q61H | Hetero | rs17851045 | |

| KRAS2 | 3845 | c.186_194 del | p.E62_Y64 | Homo | ||

| PIK3CA | 5290 | c.928 C>T | p.R310C | Hetero | ||

| INSR | 3643 | c.356 C>T | p.A119V | Hetero | ||

| INSR | 3643 | c.2243 C>T | p.S748L | Hetero | ||

| LTK | 4058 | c.728 G>A | p.R243Q | Hetero | ||

| LTK | 4058 | c.1603 G>A | p.D535N | Hetero | ||

| MERTK | 10461 | c.2069 C>T | p.T690I | Hetero |

| Normal | Patient | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIK3CA | 5290 | c.1173 A>G | p.I391M | Hetero | rs3729680 | 6 | 7.14 |

| INSR | 3643 | c.3034 G>A | p.V1012M | Hetero | rs1799816 | - | 2.4 |

| LTK | 4058 | c.125 G>A | p.R42Q | Hetero | rs2305030 | 6.7 | 24* |

| LTK | 4058 | c.680 C>T | p.P227L | Hetero | rs55739813 | - | 7.14* |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.60 A>T | p.R20S | Hetero | rs35898499 | 5.6 | 7.14 |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.1552 A>G | p.I518V | Hetero, Homo | rs2230515 | 68.3 | 100* |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.1397 G>A | p.R466K | Hetero, Homo | rs7604639 | 68 | 91.3* |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.353 G>A | p.S118N | Hetero, Homo | rs13027171 | 37.5 | 42.5 |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.2608 G>A | p.V870I | Hetero | rs2230517 | 3.4 | 18.8* |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.844 G>A | p.A282T | Hetero | rs7588635 | 0 | 7.5* |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.1493 A>G, c.1494 C>T | p.N498S | Hetero | rs35858762 | 0 | 2.5 |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.878 G>A | p.R293H | Hetero | rs34072093 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.2593 C>T | p.R865W | Hetero | rs2230516 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| MERTK | 10461 | c.2467 G>C | p.E823Q | Hetero | rs55924349 | - | 1.25 |

Gene ID at National center for biotechnology information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez)

del., deletion

Homo, homozygous; hetero, heterozygous

p<0.05

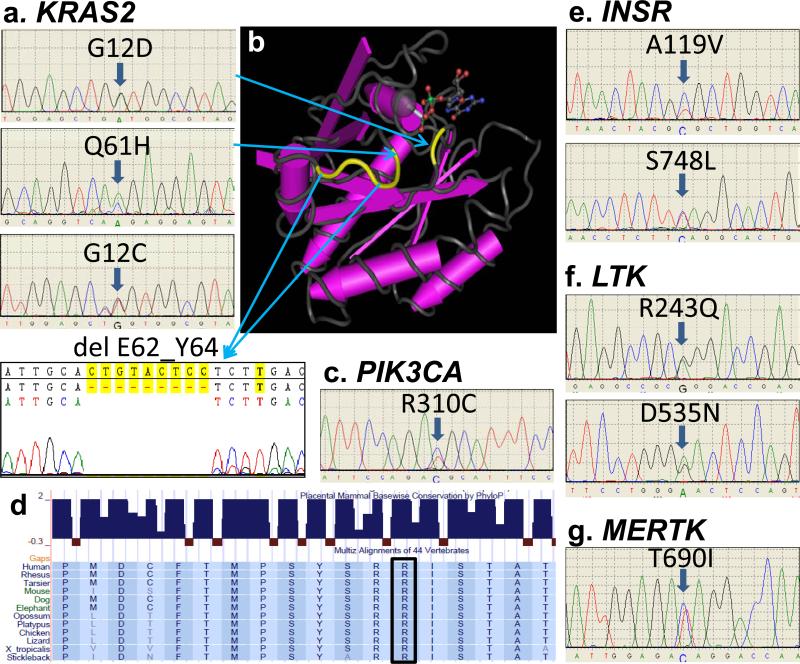

Figure 1. Ras and RTK mutational spectrum in MM.

(a) KRAS mutations G12D, Q61H, G12C and the 9bp deletion, del E62_Y64. (b) KRAS mutations (yellow) in the Ras domain structure. (c & d) The R310C mutation in the PIK3CA gene and the highly conserved codon R310 in various species (box). (e - g) Novel mutations in the INSR, LTK and MERTK genes.

Mutations p.G12D, p.G12C and p.Q61H in KRAS gene were observed (Figure 1a). In addition, a 9bp deletion (p.E62_Y64) was also identified. This in frame deletion and mutations at the G12 position might be involved in disrupting the binding partners in the activating RAS signaling pathway (Figure 1b). Prediction analysis, both sorting of intolerant from tolerant and PolyPhen analysis predicted that these alterations are most likely damaging. In the PIK3CA gene, apart from the p.I391M alteration we also discovered a novel p.R310C mutation (Figure 1c) but the classic hotspot mutations reported in most cancers were not observed. The p.R310C mutation has been recorded as a somatic event in the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer (COSMIC) database and is highly conserved. In silico analysis predicted that this mutation is most probably damaging, suggesting that this alteration might be pathogenic (Figure 1d). Novel mutations p.A119V and p.S748L in the Insulin receptor gene were discovered (Figure 1e). These conserved sequences of the INSR mutation, signify a potentially critical role for these mutations in myeloma. Novel mutations p.R243Q and p.D535N in LTK gene and p.T690I in MERTK gene were also observed. Most of these mutations, viz. A119V, V1012M, D535N, P227L, E823Q and R865W were also predicted to probably damage protein functions. Notably, a significant number of missense variants, predominantly in the MERTK gene were identified. Since our patients were mostly Caucasians, we compared the genotype frequency of these polymorphic mutations to the dbSNP database and found most but not all were significantly different from the normal population (Table 1).

Discussion

We identified mutations in KRAS, including previously known mutations and a 9bp deletion. NRAS sequencing did not uncover any mutation in our cohort. RAS pathway genes are known to play an important role in most cancers and are among the well studied genes involving activating mutations [17]. Studies in MM have shown that NRAS, codon-61 mutations are more prevalent compared to KRAS mutations [6], though some other reports contradict this [3]. Results from many of these mutational studies run the gamut from 100% RAS mutations to none [3, 5, 6, 8, 12]. These conflicting results may be accounted by potential factors involving sample selection and the mutational techniques employed [9]. To overcome these issues, we selected MM patients at diagnosis, without including MGUS or smoldering MM and used DNA from CD138 positive cells. In order to assess the sensitivity of our mutation detection tool, we also performed a mixing experiment of wild type with mutant allele of NRAS G12D at varying proportions and sequenced the mixture. The mutant allele was readily detected when present at concentrations as low as 10%. This range of sensitivity found in our study is consistent with Sanger sequencing and other methodologies used to detect RAS mutations in MM [6, 9].

Using the whole genome sequencing approach, Chapman et al [12] identified a higher frequency of NRAS and KRAS mutations in myeloma compared to our report. While we cannot rule out variability due to technique, the most likely explanation for this discrepancy in mutation frequency may be related to differences in sample characteristics between the two studies. An important difference between the Chapman study and this study needs to be stated. The Chapman study included both treated and untreated patients. When only untreated patients are compared, the frequency of KRAS mutation is comparable: 6 vs. 4 found in our study. That said, there is no clear explanation for the discrepancy of NRAS mutations which is yet to be clearly established in MM patients. By and large, resequencing of MM patient samples identified low frequency of KRAS mutations and no NRAS mutations, and these findings are in keeping with earlier studies [7, 8].

PIK3CA plays an important role in regulating cell growth, transformation, adhesion, apoptosis, survival and motility, and mutations in this gene have been reported in many cancers [18]. Our resquencing analysis of the PIK3CA gene confirmed recent findings in MM patients who did not show three PIK3CA hot spot mutations [19]. Interestingly, the initial whole genome sequencing of MM too failed to identify any mutations in PIK3CA [12]. Taken together, the low incidence of PIK3CA mutations and the absence of the hotspot mutations in MM studies suggest that PIK3CA gene might not be critical in myeloma's pathogenesis. Considering PIK3CA's critical function in many other cancers, additional studies in larger cohorts are needed to further our understating of the role played by PIK3CA in myeloma.

Mutations in the TK genes have also been extensively studied and it has been shown that high frequency of somatic mutations exists in many types of cancers [20]. In addition, this family of genes has also shown great promise in identifying druggable targets in cancer. Claudio et al [2] used high throughput screening in receptor TK pathway gene domains and identified mutations in some members of the TK gene family in MM. We hoped to identify novel mutations by screening the entire gene in this family as opposed to gene domain screening and discovered novel mutations in the insulin receptor gene, LTK and MERTK genes. The INSR protein product is expressed in MM cells and is shown to increase throughout the normal plasma cell differentiation [21]. These mutations were highly conserved and some of them were predicted to be intolerant using prediction analysis. Surprisingly, none of these novel kinase mutations observed in our study were reported in the initial MM whole genome sequencing report [12]. Although we observed these mutations at a low frequency in our study, conserved kinase mutations are known to affect protein expression, and could play a pathogenic role in MM. The role of kinase genes in targeted therapeutics in cancer is well established and modulating or inhibiting these mutated genes or their downstream pathway might also have a potential role in MM pathogenesis. In addition, significant differences in these genotype frequencies might serve as a useful biomarker for detecting myeloma specific targets especially if validated in a larger study groups.

In summary, we identified 3 known somatic mutations in KRAS gene and 7 novel mutations in cytokine signaling genes in MM. A large number of these polymorphic mutations were significantly predominant in our patients suggesting a possible role in these alleles specific to MM pathogenesis. Although the role of RAS mutations is not yet clear in defining the pathogenesis of MM, the novel TK mutations identified in this study have to be functionally validated and its relevance needs to be measured in the milieu of other genetic aberrations in myeloma.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1 – (a-d) Heat map of the expression data from GEO accession GSE755, generated using Function Express and GCOS to prioritize the RTK and Ras pathways genes. (e) The prioritized candidate genes used for resequencing analysis.

Supplementary Figure 2 – Spectral differences of NRAS – G12D allele in a serially diluted mutant allele (H929 line) and the normal allele (U266) used as a sensitivity test to capture the mutation in the presence of low percentage of mutant allele mix. Mutation was observed when at least 10-20% of cells harbored the mutant allele.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Department of Pathology & Immunology and Division of Oncology at Washington University School of Medicine, and NCI grant (#1R21CA116168). We thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, MO., for the use of the Biomedical Informatics Core, which provided the in silico analysis service. The Siteman Cancer Center is supported in part by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842.This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship Contribution

M.H.T, J.F.D, R.V and S.K Conceived the project, R.V, M.H.T and C.M Identified and collected samples, V.H, R.M, R.N Analyzed the data, V.H, R.M and S.K wrote the paper.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

None

Reference

- 1.Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23:2210–21. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claudio JO, Zhan F, Zhuang L, et al. Expression and mutation status of candidate kinases in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1124–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bezieau S, Devilder MC, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. High incidence of N and K-Ras activating mutations in multiple myeloma and primary plasma cell leukemia at diagnosis. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:212–24. doi: 10.1002/humu.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onwuazor ON, Wen XY, Wang DY, et al. Mutation, SNP, and isoform analysis of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) in 150 newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2003;102:772–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu P, Leong T, Quam L, et al. Activating mutations of N- and K-ras in multiple myeloma show different clinical associations: analysis of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase III Trial. Blood. 1996;88:2699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalakonda N, Rothwell DG, Scarffe JH, et al. Detection of N-Ras codon 61 mutations in subpopulations of tumor cells in multiple myeloma at presentation. Blood. 2001;98:1555–60. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intini D, Agnelli L, Ciceri G, et al. Relevance of Ras gene mutations in the context of the molecular heterogeneity of multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol. 2007;25:6–10. doi: 10.1002/hon.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin P, Santon A, Garcia-Cosio M, et al. RAS mutations are uncommon in multiple myeloma and other monoclonal gammopathies. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1023–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chng WJ, Gonzalez-Paz N, Price-Troska T, et al. Clinical and biological significance of RAS mutations in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:2280–4. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens P, Edkins S, Davies H, et al. A screen of the complete protein kinase gene family identifies diverse patterns of somatic mutations in human breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2005;37:590–2. doi: 10.1038/ng1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian E, Zhan F, Walker R, et al. The role of the Wnt-signaling antagonist DKK1 in the development of osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2483–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ley TJ, Minx PJ, Walter MJ, et al. A pilot study of high-throughput, sequence-based mutational profiling of primary human acute myeloid leukemia cell genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14275–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335924100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomasson MH, Xiang Z, Walgren R, et al. Somatic mutations and germline sequence variants in the expressed tyrosine kinase genes of patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:4797–808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen K, McLellan MD, Ding L, et al. PolyScan: an automatic indel and SNP detection approach to the analysis of human resequencing data. Genome Res. 2007;17:659–66. doi: 10.1101/gr.6151507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinlan MP, Settleman J. Isoform-specific ras functions in development and cancer. Future Oncol. 2009;5:105–16. doi: 10.2217/14796694.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karakas B, Bachman KE, Park BH. Mutation of the PIK3CA oncogene in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:455–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ismail SI, Mahmoud IS, Msallam MM, Sughayer MA. Hotspot mutations of PIK3CA and AKT1 genes are absent in multiple myeloma. Leuk Res. 2010;34:824–6. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sprynski AC, Hose D, Kassambara A, et al. Insulin is a potent myeloma cell growth factor through insulin/IGF-1 hybrid receptor activation. Leukemia. 2010;24:1940–50. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1 – (a-d) Heat map of the expression data from GEO accession GSE755, generated using Function Express and GCOS to prioritize the RTK and Ras pathways genes. (e) The prioritized candidate genes used for resequencing analysis.

Supplementary Figure 2 – Spectral differences of NRAS – G12D allele in a serially diluted mutant allele (H929 line) and the normal allele (U266) used as a sensitivity test to capture the mutation in the presence of low percentage of mutant allele mix. Mutation was observed when at least 10-20% of cells harbored the mutant allele.