Abstract

Background and Objectives: Inpatient palliative care (IPC) consults are associated with improved quality of care and less intensive utilization. However, little is known about how the needs of patients with advanced illness and the needs of their families and caregivers evolve or how effectively those needs are addressed. The objectives of this study were 1) to summarize findings in the literature about the needs of patients with advanced illness and the needs of their families and caregivers; 2) to identify the primary needs of patients, families, and caregivers across the continuum of care from their vantage point; and 3) to learn how IPC teams affect the care experience.

Methods: We used a longitudinal, video-ethnographic approach to observe and to interview 12 patients and their families before, during, and after an IPC consult at 3 urban medical centers. Additional interviews took place up to 12 months after discharge.

Results: Five patient/family/caregiver needs were important to all family units. IPC teams responded effectively to a variety of needs that were not met in the hospital, but some postdischarge needs, beyond the scope of IPC or health care coverage, were not completely met.

Conclusion: Findings built upon the needs identified in the literature. The longitudinal approach highlighted changes in needs of patients, families, and caregivers in response to emerging medical and nonmedical developments, from their perspective. Areas for improvement include clear, integrated communications in the hospital and coordinated, comprehensive postdischarge support for patients not under hospice care and for their caregivers.

Introduction

Fueled by shifting demographics and increasing public acceptance, the demand for palliative care services can be expected to expand in the coming years. The organization sought to understand the nature of the needs of patients with advanced illness, their families, and caregivers; describe any changes in needs; determine whether their needs were addressed; and learn their impressions of inpatient palliative care (IPC) consults. We report here on the results of a 2-pronged exploration: 1) a summary of the literature on needs, and 2) a longitudinal qualitative investigation of the experiences of 12 patients and their families with IPC teams and their subsequent experiences to inform quality-improvement efforts. After the findings are described, a narrative describing typical family experiences is provided.

Findings From the Literature: Needs of Patients, Families, and Caregivers

A broad survey of the literature was conducted to identify empirical studies and review articles that describe patient, family, and caregiver needs at end of life and how well those needs were typically met.

Information

Patients with advanced illness and their families sought clear, consistent information about the patient's condition and treatment options, but they frequently received insufficient information.1–4 In one study, more than 50% of 276 patients with lung cancer reported that their physicians did not communicate about practical needs, choice of surrogate decision maker, spiritual concerns, emotional symptoms, life-support preferences, living wills, and/or hospice.5 This applied even to older patients with advanced disease.

The importance of understanding patient care preferences becomes apparent during a crisis. In a study of 179 patients recommended for withdrawal of life support, only 3.4% of those in intensive care units had the capacity to make known their wishes for care (physicians' perspective),6 which leaves difficult decision making to distressed family members if there are no documented care directives.7

The means of conveying information is pivotal. The importance of avoiding the perception of abandonment has been emphasized.8–10 A survey of bereaved family members found that high levels of distress and low satisfaction are associated with phrases such as, “There is nothing more I can do for you.”11 Discussing what actions can be taken to promote comfort might be more productive.12,13 A study analyzing speech patterns during IPC consults revealed that longer consults did not earn higher communication ratings than shorter consults. Better consult ratings were linked to a higher proportion of patient-family speech relative to physician speech. On average, families spoke 29% of the time.14

Access to Medical Care

Seriously ill patients and their families required timely access to coordinated medical care and symptom management. Patients wished to have a trusted personal physician; to be free of pain, symptoms, and anxiety; to avoid prolonged dying; and to maintain mental alertness,10,15,16 but families reported having too few visits with health professionals and inadequate symptom control.17,18 Various health system barriers were described by patients and families, including multiple physicians and conflicting information from physicians and staff unfamiliar with issues related to the dying.3

Ability to Make Care Choices

Patients wanted to consider their options, to put their choices in writing, and to have those choices honored.2,15 This occurred more frequently when the patient participated in advance care planning.19 Interviews with caregivers revealed that patient preferences for medical care can evolve. Some patients who initially sought invasive, life-sustaining treatment shifted toward palliative goals as their illness progressed.20

Well-being of Patients, Family, and Caregivers

Patients often focused on the well-being of their family members. Steinhauser16 found patients generally wished to avoid being a burden on family, to have conflicts resolved, to know the family was prepared for their death, and to have an opportunity to say good-bye. Patients typically valued having family members present during advance care planning meetings.

Coming to peace with God and being able to discuss spiritual beliefs was important to many patients.16

Caregivers often found supporting a loved one to be a meaningful experience, but it could deplete time, financial resources, mental health, and physical health.21 A study of 392 caregivers and 427 noncaregivers found mortality risks were 63% higher among stressed caregivers than among noncaregiver controls, after adjustments for demographics and subclinical disease.22 Information and support provided to caregivers have frequently been described as inadequate.1,3,10,17,18

Palliative Care Interventions Designed to Meet Needs of Patients with Advanced Illness

To meet the complex medical and communication needs of patients and families in the hospital setting, IPC consultations were developed to deliver holistic, patient- and family-centered care. They were designed with the objectives of managing symptoms; helping patients reflect on their values; explaining care options; appointing a proxy; documenting goals of care; meeting psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients and family members; and supporting planning for future care.

Randomized controlled trials and other studies have demonstrated that palliative care consultations, especially by multidisciplinary teams, can have a favorable impact on readmissions, intensive care unit admissions, use of hospice, costs, and the care experience.10,23–31 Increased median longevity was observed among patients with small-cell lung cancer in early referral outpatient palliative care settings versus usual care.32 Patients provided with inpatient palliative care consults were less likely to die in intensive care units and more likely to receive hospice referrals.25 Consults in outpatient and inpatient settings can improve pain management, symptoms, quality of life, depression, and anxiety.32,33

Patient and Family Satisfaction and Well-Being after Palliative Care Consults

Several studies have documented a positive impact of IPC consults on the care experience. A telephone survey of caregivers of patients receiving IPC services found that 95% of respondents said they would be likely to recommend the service.29 A multisite Veterans Administration survey of 524 family members found that patients who had an inpatient or outpatient consultation were significantly more satisfied with information, communication, access to care, emotional and spiritual support, well-being, and dignity and care at death than families of patients who did not.34 Early referral, which can increase the use of hospice services, maximizes the value of IPC consults. Longer hospice stays improved quality of life for patients, which in turn was associated with better quality of life for caregivers.35

Widespread Unmet Need

Despite the rapid growth of palliative care, many patients have not discussed or documented their wishes. The California Healthcare Foundation surveyed 1669 adult Californians and found that 70% preferred to die at home, but only 32% did. Nearly 80% would have liked to speak to their physician about end-of-life care if seriously ill, but less than 7% had ever participated in such a conversation.36 Another California Healthcare Foundation survey found that only 44% of 373 respondents who had experienced the death of a family member in the last 12 months felt that the patient's wishes were completely followed and honored by providers.37

Longitudinal Video-Ethnographic Study

Background and Objectives

Implementation of IPC programs has spread rapidly across the US and abroad. In 2011, 85% of US hospitals with 300 or more beds had palliative care programs.37 Inpatient palliative care services are available at all Kaiser Permanente (KP) Medical Centers.38

To understand the care experience of patients and their families, KP Care Management Institute surveyed families of patients who had died several months before (unpublished data, 2009). A thematic analysis of 1212 verbatim comments identified a variety of patient, family, and caregiver needs (unpublished data, 2009). The findings revealed some challenges, but the brief comments did not describe the sequence of events behind them. The survey of families did not include the patient's perspective or describe how patients and families experienced IPC consults. In-depth, longitudinal case studies investigating the care experience are needed to supplement findings of the large-sample survey and inform strategies to improve the quality of IPC and the care experience.

Methods

A series of 12 case studies was conducted using a form of anthropologic inquiry, video-ethnography. Ethnographic research is designed to uncover participant perspectives through sustained, naturalistic observation of and engagement with informants over time. In-depth understanding of a few participants is acquired, in contrast to a limited understanding of a large number of participants.

The study included 12 patients who received care at 3 Medical Centers, and their families and caregivers. We recruited patients who were scheduled for an IPC consult on the days the study team visited the site. Exclusion criteria included families who did not speak English, patients whose death was imminent, and patients with no family member attending the consult. To the extent possible in a small sample, we targeted patients with diverse diagnoses and diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds who were able to participate in consults and who had life expectancies longer than 3 months. Physicians and nurses who were most familiar with the patients invited them to participate. The interviewer administered consent forms to interested patients and families. Semistructured interviews were conducted from October 2009 through December 2010.

Patients and families were observed and videotaped by an interviewer-videographer team before, during, and after the IPC consult. Interviews took place before and after the consult. After the consult, they were asked about their impressions of the IPC team, about their own priorities, and whether they had unanswered questions. Participants were encouraged to share family stories. One or more follow-up IPC team visits were recorded in the hospital, followed by additional interviews.

During visits in the following weeks and months, patients and families were interviewed in their home, assisted-living facility, hospital, or skilled nursing facility. Participants were asked how they were faring, what events had transpired, what health care contacts they had made, what needs they had, and what concerns were most important for each family member. We observed the environment and how patients and families functioned.

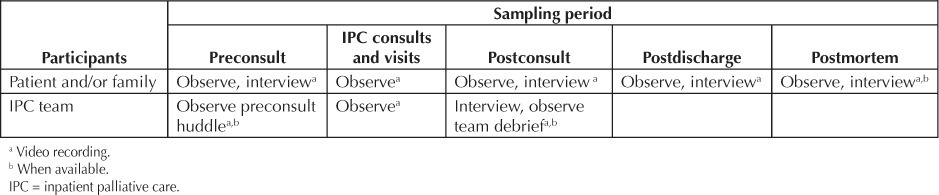

We learned about consults and patient care from the perspectives of participants in different roles (patients, families, caregivers, and IPC teams) and on multiple occasions. The variety of data sources contributed to a deeper understanding of the context and course of the end-of-life experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sampling approach

Initial need themes were based on the needs identified in the literature and the analysis of verbatim responses from the survey of bereaved family members. Themes and subthemes were developed iteratively using the constant comparative method.39 Transcribed interviews and 70 hours of videotape were reviewed to develop themes and later to apply the final codes.

Observers who participated in data collection contributed to theme development. Two coders independently applied the final codes to transcribed and videotaped interviews and resolved discrepancies. Analysis was conducted with ATLAS.ti qualitative analysis software (v5, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and Microsoft Excel (XP Professional, 2003, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). We tallied met and unmet needs in each case to determine the prevalence of each need and to test hypotheses. Selection criteria for final need themes were 1) on the basis of participants' perspectives rather than an organizational perspective; 2) pervasive importance across patients and families; and 3) together the need themes should encompass all major issues raised by participants.

The study proposal was reviewed by the KP institutional review board. Participating patients and family members were informed of their rights and gave written, informed consent.

Results

Participants: Five IPC teams from 3 urban KP Medical Centers volunteered to participate. The classical elements of palliative care consults delivered by an interdisciplinary team (eg, the 4-discipline team observed by Gade et al24) were not present at all sites. Three teams comprised various combinations of team members (physician, nurse, social worker, and chaplain). Two teams provided consults by a single practitioner (nurse or physician) with follow-up visits by a social worker. Both approaches tended to include more than one visit with the patient, family, or both. Preparatory visits and follow-up visits were often attended by a subset of the team (just the physician, nurse, or social worker; or two members.) Thus the “team” intervention was not a fixed, single intervention. Visits included early assessment by one team member; full consults typically lasting 30 to 60 minutes; additional family conferences; visits to complete care directives; and meetings to help with postdischarge needs. Each visit offered opportunities for patients and family members to ask new questions and assimilate the information. When interdisciplinary teams sensed that a visit from a large team might be burdensome, they limited team size.

Patients referred for palliative care consults tended to be very old, have moderate to advanced dementia, and/or be close to death. The recruiting criteria aimed to maximize the number of patients who could participate in the consult with family members present. All eligible patients scheduled for consults were invited; approximately 50% of the families agreed to participate. One third of the participating patients were men. Patient ages ranged from 46 to 89, including 3 women with cancer who had younger children. Diagnoses included cancer, dementia, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, aortic aneurysm, diabetes, and infections. Ten of the 12 patients were able to participate in the consult. Patients were discharged to home hospice care (n = 5), skilled nursing facilities (n = 2), or home health services (n = 4). One patient died in the hospital. The sample was not as diverse as we preferred: 10 patients were Caucasian, 1 was Latina, and 1 was Asian.

The one-year longitudinal study yielded 70 hours of transcribed, videotaped consults and interviews with patients and families, in addition to phone contacts, transcripts, and field notes. The database included 35 consults and follow-up team visits and 31 visits with families.

Patient, Family, and Caregiver Needs: Five major need themes central to the patient, family, and caregiver experience were identified: 1) sensitive, effective communication about advanced illness; 2) timely access to coordinated medical care; 3) respect for and honoring care decisions; 4) psychological, social, and spiritual needs; and 5) caregiver support. The degree to which the needs were met varied across patients and families and over time. The needs of some patients and families were initially not met but were later resolved. The needs of other families were met in the hospital but were not fully addressed after discharge. The 5 need themes were important to all 12 families. The needs of greatest importance to a family typically fluctuated over time.

Sensitive, Effective Communication About Advanced Illness

During hospital stay, patients with advanced illness and their families had a variety of communication needs. Before the IPC consult, they sought information about the patient's current status, test results, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology, what to expect, and what actions to take. Most reported being confused by medical jargon and being unable to integrate the information. One family reported feeling they were receiving conflicting information about the patient's condition and prognosis, with nobody explaining the “big picture.” Some families believed that a few hospital physicians and staff did not show respect for older, sick patients.

The IPC teams communicated effectively and sensitively. They were sometimes described as compassionate or caring. Patients and families frequently remarked that the team did not rush them. When in doubt, the teams sought permission to discuss sensitive topics. The patient and family were encouraged to share past experiences and honor or celebrate the patient's accomplishments and relationships.

The team explained in nontechnical language the patient's past and current condition and implications for functioning in the immediate future. When asked about the patient's functioning at home, the patient and family gave answers that raised their awareness of a poor trajectory. The team helped to bring patients and families to an understanding the patient was not expected to improve. The teams set expectations for life after discharge, normalizing events the patient and family might experience. Families had many questions and especially valued having extended time with a physician.

Caring was communicated through touch, gestures, and attitude. One patient remarked, “The doctor smiled. I am so tired of sad faces.” Other team members responded to questions after the consult. Overall, the families felt their information needs were being met. After the team left, one family member said, “This is the first communication we have had!”

Team leaders frequently used reframing statements, metaphors, and analogies to help families and patients know what to expect, chart a course for the future, find meaning, and enhance family relationships.

Overall, the structure and sequence of the consults were similar across patients, although the content varied somewhat. For example, adult children with parents unable to make decisions struggled with the responsibility of making serious decisions and needed support. Patients with young children wanted their children to know they fought the disease valiantly, even when they understood their prognosis. Two mothers with cancer made a distinction between this battle and denial.

Two families were concerned that palliative care might imply giving up on the patient. Despite trepidation about having an IPC consult, these patients and families said they were comfortable with team communications. They felt the teams were helpful. (Over the following months, participants voiced a variety of complaints about their care experience, but IPC team communications were not a source of dissatisfaction.)

The most frequent comments about the IPC teams concerned their helpfulness, respectful treatment of patients and families, clarity of communications, and the amount of time they spent with the family.

Some barriers to effective communication with families were observed. One family member struggled to understand the meaning and purpose of “palliative care.” Three families had a member whose hearing impairment reduced the effectiveness of the consult.

Timely Access to Coordinated Medical Care

Before the consult, some patients and families felt they “had to push” to have their medical needs addressed. A few patients and family members felt their access to physicians with answers to their questions or test results was not timely. The teams worked as patient advocates to resolve problems, to coordinate care, and to answer questions.

Most patients needed help with pain or other symptoms that would reduce their ability to participate comfortably in the consult. Symptom control was improved before the family meeting and fine-tuned over time.

Before the IPC consult … Most reported being confused by medical jargon and being unable to integrate the information.

After discharge, challenges included some issues that were not covered by benefits. Discharges were generally smooth and medical needs were initially met. New symptoms or practical problems emerged later. Patients under hospice care and patients who reconnected with their primary care physicians soon after discharge were generally comfortable, and their medical needs were addressed. Some caregivers of patients who were not under hospice care observed new symptoms and were not sure how to help the patient. They sought a point of contact for questions about emerging medical conditions and practical needs (such as caring for the patient and transportation to the medical office). Four of the 12 patients were treated in the Emergency Department or were readmitted to the hospital on one or more occasions. One family was dissatisfied with the quality of medical care at the nursing home.

Respect For and Honoring Care Decisions

Most patients had strong preferences about where they would live after discharge and the intensity of care they would receive (eg, not wishing to be sent to a skilled nursing facility or not wanting hospice care). One patient had distressing memories of her husband's living with advanced dementia in a nursing home and was terrified she would be sent there. One couple was haunted by the mechanical ventilation of their daughter after a stroke. They had to “pull the plug” and did not want to endure that again. Two patients initially sought expedited death.

Several patients and family members felt that some IPC teams or other physicians or staff they encountered in the past had pressured them into making a decision too soon or had pressured them into making a particular choice. They did not have that impression of any of the study teams. In contrast, several families appealed to the physician to help make decisions for them. The 12 patients and their families felt that the teams accepted and respected their decisions.

Preferences of three of the families shifted toward palliative care as patient fatigue increased. The patients and families in the study were pleased that their wishes were honored. All care at end of life was in accord with patient decisions.

Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Support

The IPC teams were sensitive and respectful to patients and families and responsive to individual and cultural differences. Patients and families had to process a substantial volume of new medical information. The teams adjusted their pace and approach to meet the needs of different families. They provided direction and promoted a sense of meaning and purpose. Although the five teams used a variety of interaction styles, patient and family impressions of their interactions with the teams were positive.

Some patients or families sought and obtained access to a psychotherapist for young children of mothers with cancer or for patients. Two families suggested psychotherapy outreach for young children.

Spiritual support was offered during consults, but families with religious affiliations in this sample said they would consult their own clergy and felt comforted by their faith. Only three families saw a team with a chaplain. Inclusion of more teams with chaplains might have produced more detailed information about spiritual experiences.

Caregiver Support

The need for caregiver support varied by the type of care received after discharge. Patients under hospice care tended to be close to death. Most described hospice care as “wonderful” and reported no unmet needs. The most frequently mentioned feature of hospice care was that hospice staff “knew just what to say.”

Some caregivers of patients not under hospice care felt ill-equipped to care for the patient. Two families sought education for safe caregiving in the home, such as moving, toileting, and bathing. For one family, costs associated with transportation to the primary care physician's office were a barrier to receiving care. One caregiver whose father required hourly care took a leave of absence from her job to care for him. She was proud of keeping him free of pressure ulcers, but continuous caregiving took a heavy toll on her. Her faith sustained her, but she missed her career and her freedom. The daughter of another patient living at home greatly reduced her work hours to care for her father, who had increasingly unmanageable dementia. One caregiver became seriously ill while caring for her husband.

Discussion

Evolving Needs Over Time

The 5 need themes were evident throughout the patient/family journey, but the prominence of each need varied over time. Before the consult, most families had compelling needs for information; psychological, social, and spiritual support; and access to care. During the consult, all 5 needs were evident. In the weeks or months thereafter, the need for information, caregiver support, and access to care intensified for some families. Psychological, social, and spiritual needs were present throughout the observation period but appeared to be set aside when other urgent needs emerged. A composite case study (see section: Richard's Palliative Care Experience, page 33) based on experiences of the 12 patients and their families highlights these findings and illustrates the developing needs and the strengths and challenges of the current care delivery system.

Limitations

The study design may have introduced bias from the following sources: convenience sampling of experienced IPC teams/sites; provider selection of patient/family units (possibly favoring gregarious, articulate, and stable families); unknown influences because of the presence of observers; limited number of consults addressing spirituality; and limited diversity. The study included only English-speaking patients and patients with family present at the time of the consult. The sample size does not permit analyses of subgroups based on factors of interest, such as team configurations and patient demographics.

Implications

This study opens a window into the end-of-life journey across the continuum of care. The findings point to the need for accessible language; respect for care decisions; and consistent, coordinated messages in the hospital. We observed the tendency of physicians to make IPC referrals for patients near death. The potential value of the teams is not realized by late referrals. Outpatient and inpatient consultations earlier in the disease process might improve appropriateness of care and increase the likelihood of patients receiving preferred care.

The most conspicuous gaps in the care experience were observed after discharge. The postdischarge support features that were essential in this sample were:

understanding normal symptoms versus red flags, and how to respond;

point-of-contact for information on medical and nonmedical needs; and

communication with medical provider soon after discharge (nonhospice patients);

training for in-home caregiving (eg, moving, toileting, and comfort needs);

care for the caregiver (including medical needs).

This list reinforces existing postdischarge checklists40,41 that include interventions to address gaps and adds caregiver needs. Many postdischarge needs were outside the scope and influence of IPC team care and sometimes beyond the reach of health care coverage. Families of patients who are at high risk but not ready or eligible for hospice may need enhanced support, including practical support for caregivers. The best-laid plans may fail in complex cases where transitions in patient care are not managed consistently and access to comprehensive, coordinated outpatient support is lacking. In the absence of such a tightly woven safety net, the Emergency Department becomes the default destination when new symptoms arise.

A variety of services could provide postdischarge supplemental or palliative care, including transitions management programs. Outpatient palliative support may play an important role in addressing deficiencies in the care experience.42–44

In terms of new interventions, the nature of this study does not permit specific recommendations, but the findings point to five needs that are consistently experienced by patients and their families and caregivers.

Implications for future research include the need for large-sample studies to replicate the findings and estimate the pervasiveness of the needs in the larger population. Future studies could explore differences associated with team staffing, perceptions within a variety of patient subgroups, IPC team communication skills and strategies, and the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve the postdischarge experience. A study of the perceptions of palliative care services among hospital and ambulatory care physicians and nurses could help palliative care teams understand barriers to appropriate referrals.

Richard's Palliative Care Experience: A Composite of Patient/Family Experiences

Preparation for Richard's Inpatient Palliative Care Consult

Richard, age 72 years, was a high school teacher and football coach.a This 10-day hospitalization was his third emergency admission this year. He was treated for acute renal failure and congestive heart failure and underwent hemodialysis. Richard was struggling with pain and dyspnea. His attending physician recommended the family meet with the IPC team.

Richard's daughter Beth was pleased the family could meet with the team. She was confused because previous physicians had different perspectives on Richard's status; she wanted to understand the big picture of her father's condition and prognosis. Should she encourage out-of-state family members to come soon? Beth was concerned that family members were not all on the same page. Those without first-hand experience with his series of medical crises were insisting on heroic measures to extend his life. In contrast, Richard explained he was tired of fighting and wanted to go home and get back to his life.

Richard's wife, Lisa, told the nurse she did not understand why her husband was so sick now. She said, “He was doing so well. What happened?” The last physician told her his condition had improved. She was certain he just needed to start walking again.

Dr Lewis, the IPC team lead, visited Richard before the full team consult. He determined that adjustments to Richard's medications could reduce his symptoms and conveyed his recommendations to Richard's physician. The IPC nurse scheduled a meeting with Richard, the team, and four family members. Before the consult, the IPC team met to discuss Richard's clinical status, psychosocial needs, care preferences, and the family's concerns and resources. They discussed the variation in family members' understanding of Richard's condition and developed a strategy tailored to the family.

Outpatient palliative support may play an important role in addressing deficiencies in the care experience.

Richard's Inpatient Palliative Care Consult

After assessing Richard's comfort level, Dr Lewis introduced the team, explained their role, and described how they could help Richard and his family:

“We are the palliative care team. We meet with patients and families of patients who have serious illnesses. We address all issues of comfort and quality of life to make sure that we're doing everything we can to make Richard comfortable and be sure you have all the information you need. We try to understand what's important to you and how your family is doing. It's been a difficult illness for Richard, and it's going to be a long, potentially difficult recovery process. We want to talk about that and plan for the future.”

He asked Richard and the family about his experiences and learned about Richard's passion for the school's football team. Richard was able to help a few boys enter college. Then Dr Lewis asked about Richard's current activities, which transitioned naturally into a functional assessment.

As the family responded to questions, they recognized that Richard's functional trajectory was not improving. Recently, Richard had stopped attending football games and had turned the household finances over to his wife. Lisa was his primary caregiver, but she had her own health problems (diabetes, hypertension, and arthritis), and he feared being a burden on her. The team inquired about the family's resources to care for Richard.

Dr Lewis asked Richard to describe his understanding of his condition and his concerns. Richard had a sense of his overall status. Dr Lewis explained, “Richard, the concern the doctors have is that hospitalization is going to take some of your strength. You are going to feel different than before you came to the hospital.” He asked permission to advance the discussion. “Do you want to know how your body might be different?” Richard replied, “That is what I want to know.” Dr Lewis continued, “When you came in, you needed kidney dialysis. Your kidneys function half as well as they did when you were younger. The other thing that's different is your heart isn't as strong as it used to be, so you will feel tired faster …. Some function will come back, but not all. So we just have to go step by step.”

Dr Lewis wove all the apparently unrelated medical events and messages from various physicians into a coherent explanation in plain language and discussed goals of care. He helped set expectations for normal changes in the next few weeks. Richard learned about the likely poor outcomes of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation given his debility, renal failure, and impaired cardiac function. He decided he would prefer to be allowed to have a natural death in the event of a cardiac arrest. He did not want care in a nursing home for rehabilitation or to have aggressive care to save his life if he was unlikely to be able to interact with his family. He was tired. Richard chose his wife to be his proxy.

Lisa was certain that Richard would recover. The hospice care option was presented but not pushed; there would be time to reconsider. The family learned about their home health support options.

The social worker observed that son Richard Jr, who had just arrived from Chicago, had not fully grasped his father's condition until now. The team adjusted the pace of the discussion accordingly. The social worker spent time with Richard Jr after the consult to answer questions and help him with his feelings of guilt.

After the Inpatient Palliative Care Consult

After the IPC team left, the family was asked for their impressions. Richard was satisfied with the meeting. He asked his family to support each other instead of bickering.

Beth was pleased that the family now had a common understanding of Richard's condition and a concrete post-discharge plan. She appreciated the hour with the physician, saying, “He answered questions in my language and said things in a way we can understand … The doctor said, ‘This is what's going to happen,’ … and it wasn't rushed. He spent time explaining. You have to spend time ... especially in a situation like this.”

Lisa feared she lacked the skills and strength to care for Richard in his weakened condition. She said, “He is a big man and he is not walking now. Somebody's got to tell me what to do. What's the plan? How do I lift him?” Beth was concerned about her mother. During the previous two months of caring for Richard, Lisa would often have to stop and rest.

The IPC team debriefed after the meeting. They discussed whether they had advanced the conversation at the right pace and whether family members could assimilate what they heard. The nurse mentioned that Richard's daughters had additional questions; she would meet with them before they left for the day. The recommended changes to the treatment plan, revised code status, goals of care, and the family's perspectives were communicated to Richard's physicians and nurses. Lisa and Beth later met with the team social worker to discuss Richard's postdischarge needs and financial concerns. The nurse visited Richard and Lisa the next day to answer their new questions and formally document his wishes. Lisa said, “I know what I need to know. We have a plan, for now.”

After Discharge

Richard was discharged to his home, as he wished, with the support of home health care services, physical therapy, and his primary care physician. The transition was smooth, but Lisa struggled with moving Richard. Beth took leave from work to help with his care. Beth insisted her mother visit her physician to get a checkup.

The family felt Richard looked much better after leaving the hospital. He began spending time in the family room in a wheelchair. He was delighted to be visited by five of the students he coached. Ten days later, he experienced breathlessness, pain, and anxiety. Unsure whom to contact, they brought him to the emergency room. The palliative care team detected his readmission during their daily scan of palliative care patient admissions and visited him that day. They had another consult and adjusted the treatment plan. Richard reiterated his wish not to resume hemodialysis and was able to return home. A week later, he died at home under the care of a hospice team, surrounded by his family.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Leslie E Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

a Common experiences of participating families were combined in an amalgam family to protect patient and family privacy.

References

- 1.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tatersall MH. The needs of terminally ill cancer patients versus those of caregivers for information regarding prognosis and end-of-life issues. Cancer. 2005 May 1;103(9):1957–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ. 2010 Jan 19;340:c112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson PL, Aranda S, Kristjanson LJ. Meeting the supportive needs of family caregivers in palliative care: challenges for health professionals. J Palliat Med. 2004 Feb;7(1):19–25. doi: 10.1089/109662104322737214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Meeting the needs of intensive care unit patients and families: a multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jan;163(1):135–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117. French FAMIREA Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson JE, Gay EB, Berman AR, Powell CA, Salazar-Schicchi J, Wisnivesky JP. Patients rate physician communication about lung cancer. Cancer. 2011 Nov 15;117(22):5212–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 Jan;155(1):15–20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 1;154(6):336–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon GH. Care not cure: dialogues at the transition. Patient Educ Consult. 2003 May;50(1):95–8. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Amer J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Apr 15;171(8):844–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Lorenz KA, Mularski RA, Lynn J. A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Jan;56(1):124–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01507.x. RAND-Southern California Evidence-Based Practice Center. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, et al. Communication about the ending of anticancer treatment and transition to palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2004 Oct;15(10):1551–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson DG, Tobin DR. End-of-life conversations: evolving practice and theory. JAMA. 2000 Sep;284(12):1573–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantilat SZ. Communicating with seriously ill patients: better words to say. JAMA. 2009 Mar 25;301(12):1279–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonagh JR, Elliot TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004 Jul;32(7):1484–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients' perspectives. JAMA. 1999 Jan 13;281(2):163–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp ED, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians and other care providers. JAMA. 2000 Nov;284:2476–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lecouturier J, Jacoby A, Bradshaw C, Lovel T, Eccles M. Lay carers' satisfaction with community palliative care: results of a postal survey. South Tynes-die MAAG Palliative Care Study Group. Palliat Med. 1999 Jul;13(4):275–83. doi: 10.1191/026921699667368640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bee PE, Barnes P, Luker KA. A systematic review of informal caregivers' needs in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2009 May;18(10):1379–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detering KM, Handcock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010 Mar 23;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried TR, O'Leary JR. Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient- and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Oct;23(10):1602–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life: “they don't know what they don' t know.”. JAMA. 2004 Jan 28;291(4):483–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999 Dec 15;282(23):2215–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hearn J, Higginson IJ. Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 1998 Sep;12:317–32. doi: 10.1191/026921698676226729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2008 Mar;11(2):180–90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011 Mar;30(3):454–63. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006 Aug;9(4):855–60. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penrod JD, Deb P, Dellenbaugh C, et al. Hospital-based palliative care consultation: effects on hospital cost. J Palliat Med. 2010 Aug;13(8):973–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0038. Erratum in: J Palliat Med 2006 Dec;9(6):1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison RS, Renrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Palliative Care Leadership Centers' Outcomes Group. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Sep 8;168(16):1783–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Mahony MD, Blank AE, Zallman BA, Selwyn PA. The benefits of a hospital-based inpatient palliative care consultation service: preliminary outcome data. J Palliat Med. 2005 Oct;8(5):1033–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson C, Chand P, Sortais J, Oloimooja J, Rembert G. Inpatient palliative care consults and the probability of hospital readmission. Perm J. 2011 Spring;15(2):48–51. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, et al. Family meetings in palliative care: are they effective? Palliat Med. 2009 Mar;23(2):150–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216308099960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J. 2010 Sep–Oct;16(5):423–35. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181f684e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Apr;56(4):593–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lake Research Partners, The Coalition for Compassionate Care of California. Final chapter: Californians' attitudes and experiences with death and dying [booklet on the Internet] Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation; 2012 Feb 14. [cited 2012 Jun 18]. Available from: www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/F/PDF%20FinalChapterDeathDying.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palliative care in hospitals continues rapid growth for 10th straight year, according to latest analysis [press release on the Internet] New York: Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2011 Jul 14. (cited 2011 Sep 6] Available from: www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/07-14-11. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Della Penna R, Martel H, Neuwirth E, et al. Rapid spread of complex change: a case study in inpatient palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009 Dec 29;9:245. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965 Spring;12(4):436–45. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1822–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care for older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 May;52(5):675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. Erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc 2004 Jul;52(7):1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med. 2003 Oct;6(5):715–24. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Jul;55(7):993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engelhardt JB, Rizzo VM, Della Penna RD, et al. Effectiveness of care coordination and health counseling in advancing illness. Am J Manag Care. 2009 Nov;15(11):817–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]