Abstract

Objective: To engage patients in managing their health care especially in relation to a total joint replacement (TJR). With the aging of the American population and the advent of new technology, there is an increase in TJRs. As the pendulum swings from evidence-based medicine to patient-centered medicine, presurgical education is preparing patients for their surgical experience. Most research studies on such education are quantitative in nature, preventing patients' voices from being heard.

Methods: Using a success case narrative design, 24 patients mainly from the Kaiser Permanente Downey Medical Center were interviewed regarding their pre- and postsurgical experiences.

Results: The study findings demonstrate that patient education, in the form of classes, with recognition of the participants' physical needs, social needs, concrete supports, and psychological needs as well as the willingness of the participants to work with their health care team can promote patient engagement and improved quality of life.

Conclusion: The TJR class was found to promote a sense of social connectedness and fostered participants' independence. The results of this study can assist health care professionals to improve their practice by designing presurgical programs to meet the needs of their patients.

Introduction

As the pendulum swings toward patient-centered medicine, presurgical education has been thrust to the forefront. Health care professionals are now expected to address the physical needs, social needs, concrete supports, and psychological needs of surgical patients rather than simply telling patients what to do. Patient education programs help patients improve their decision-making skills and self-efficacy. The long-term goal is for patients to take increased responsibility for their health care and to enjoy an enriched quality of life.

Information provided to patients before total joint replacement (TJR) surgery appears to have an empowering effect.1–3 However, few research reports have addressed patient perspectives of the effect of preoperative educational programs. Qualitative research based on patient perceptions can inform health care professionals so that they can implement effective programs. This study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente (KP) Southern California and University of California Los Angeles institutional review boards.

Purpose and Significance of the Study

Few narrative studies have been done for patients to communicate and give meaning to their experience of TJR. The majority of the literature considers patients from the health care professional's perspective.

With shorter hospital stays and with an increasing number of discharges to home rather than to a skilled nursing facility after TJR, there is a greater demand for presurgical education and support. How best to provide this education is up for debate.

Implications of the Study

Qualitative methods can help bridge the gap between scientific evidence and clinical practice.4 The success case narrative design of this study allowed patient voices to be heard through the din of health care professionals' pronouncements. Awareness of patient perceptions of presurgical educational programs will inform patient education and enable health care professionals to develop strategies to further facilitate return to health.

Theoretical Framework

The study design was guided by a theory of change and a logic model. The theory of change is a pathway depicting steps toward goals. The logic model lists the planned steps for implementing the program.5 In addition, this study integrates theories that engage patients to take more responsibility in managing their health care: adult learning theory and role theory.

Theory of Change

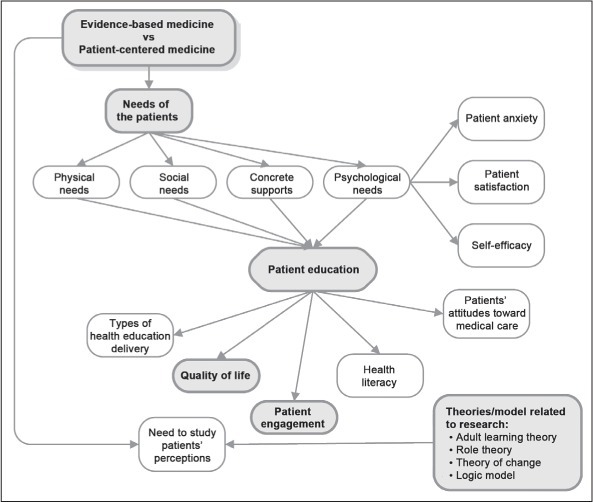

The model defined the dimensions and related concepts of the study (Figure 1). This theory of change model shows the major areas (steps) to be considered in reaching the goals of patient engagement and improved quality of life. A major benefit of this model is that it identifies expected results, including minor areas (ministeps) along the way.5

Figure 1.

Detailed theory of change for total joint replacement. Shaded boxes represent major topics.

Logic Model

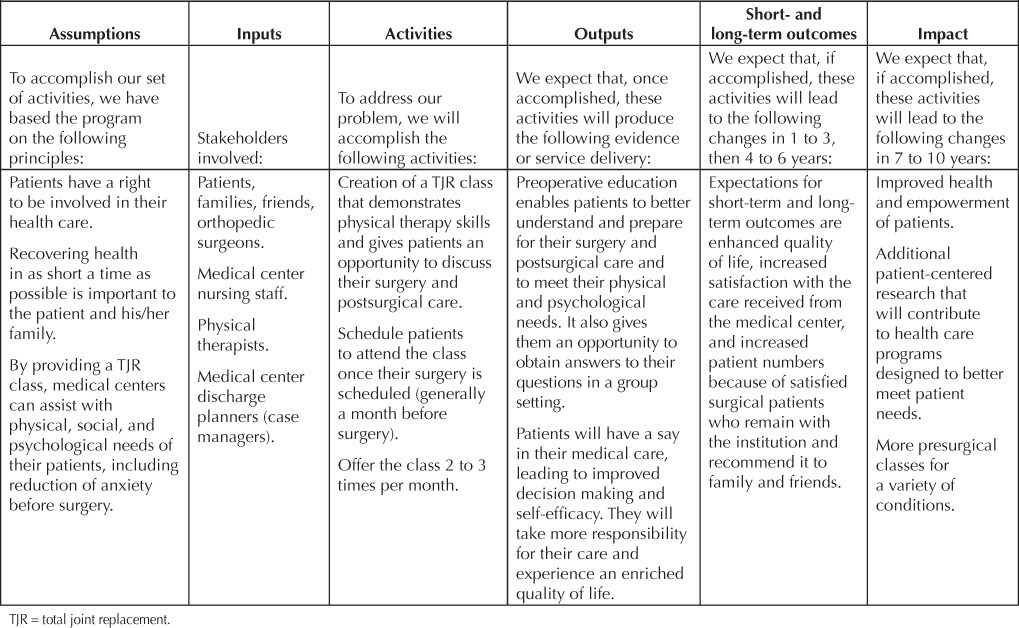

The logic model (Table 1) on which the research is based reflects the work of the WK Kellogg Foundation.6 The logic model is built on the big-picture view rather than the nuts and bolts of the program. In attempting to promote a theoretical change, this study used a logic model that incorporates the premises of the TJR Program. These include the stakeholders and the activities, such as the products, services, infrastructure, and relationships. Short-term and long-term outcomes of the program are also considered, including specific changes in attitudes, behaviors, skills, knowledge, status, and level of functioning; and overall effects on the organization and community.

Table 1.

Logic model for the total joint replacement class

Research Questions

A success case narrative research design, which uses a short survey to identify individuals who are extremely successful or not successful, followed by in-depth interviews, allowed patients to give voice to their experience of TJR. The research questions were designed to offer patients the opportunity to tell their story regardless of class attendance.

How do patients, whether they attended a TJR class or not, describe their overall TJR experience?

What are the differences in perceptions, if any, between patients who have taken the TJR class and those who have not, in terms of physical needs, social needs, concrete supports, and psychological needs, both before and after the surgery?

Whether the patients have attended the presurgical education program or not, what activities or materials do patients say helped them prepare for or recover from TJR surgery?

From the patients' perspectives, whether they have attended the presurgical program or not, what can Medical Groups do to enhance quality of life after surgery?

Methods

The gap in the literature addressed by this study is that patient voices are rarely expressed in research studies examining medical care. Academics often consider patient-centered medicine a fuzzy concept, because its ideological base is more developed than its research base.7 Hence the need for this qualitative study focusing on patient perceptions of how to engage in the management of their health care and to improve their quality of life after surgery.

Site Selection

KP, a prepaid group model health maintenance organization, was selected as the site for the interviews because it is the largest provider of total hip and knee replacements in the US.8 KP has a culture of preventive care, including many health education classes for patients.

The TJR class, which covers pre- and postsurgical information and physical therapy exercises, began at the Bellflower (now Downey) Medical Center in April 2007. The class was a response to KP orthopedic surgeons' concerns about patients approaching surgery with excessive fear and unrealistic expectations. The existing educational method was to provide the patient a Krames Staywell Company (Evanston, IL) pamphlet outlining the TJR procedure as well as a 1997 KP 24-minute DVD discussing preparation for total hip or knee surgery and recovery. It did not seem to be working. Development of the 2-hour class was a collaborative effort of the Departments of Health Education, Orthopedics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Utilization Management and included both inpatient and outpatient staff. The class is offered at least twice a month in English and monthly in Spanish. KP orthopedic surgeons strongly recommend that their patients attend the TJR class before surgery because the class has a strong reputation of assisting patients to better manage their health care.

We are not aware of any study that has been done at KP to document patient perceptions of the TJR class. In an era of budget slashing, including patient education programs, such a qualitative research study can corroborate or refute the anecdotal evidence and serve as a foundation to determine if there is a place for presurgical classes at health care institutions.

Participant Characteristics

The study sample came from KP Southern California's population of patients who underwent either total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. The sample comprised English-speaking patients (non–KP employees) mostly from the KP Downey Service Area who preferably had either a unilateral hip (total hip replacement) or knee replacement (total knee replacement) within 2009 to 2011. More than 500 patients undergo total hip or knee replacement surgeries each year at the Downey Medical Center.8

KP employees were excluded from the sample because they may have knowledge about the surgery and the KP system that non-KP employees typically do not. Patients who had undergone previous joint replacement (more than five years earlier on the same joint type or less than five years on a different joint type) or who elected to have bilateral replacements were included. Therefore, patients who had had a previous joint replacement were interviewed at least one or more years after the initial surgery to avoid perception bias related to the previous procedure. Although the perspectives of people who underwent bilateral replacements may differ from those of patients who had a single joint replacement, their perspectives were considered valuable because this type of surgery is becoming more prevalent.9,10 Because TJR is not common in pregnant women and children, these groups were excluded.

Data Collection Methods

To answer the four research questions, an interview approach was used. By using interviews and narrative analysis, the researcher looked beyond the quantitative research regarding presurgical classes.11

Selection of Participants

Participants were selected by the following critieria: Southern California KP membership, primarily in the Downey Service Area, English speaking, and non-KP employee patients, who had either a total hip or knee replacement. Prospective participants were given a recruitment letter by the discharge planner or orthopedic nurse practitioner (NP) before they were discharged from Downey Medical Center. Patients were also able to obtain an invitation letter during their postoperative orthopedic or physical therapy appointment. The letter asked patients to call the researcher within six weeks after surgery to learn more about the study.

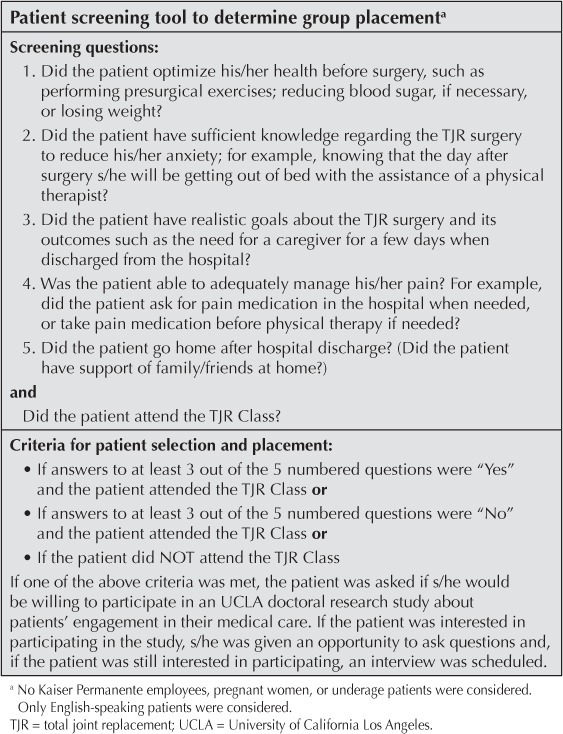

Patients were screened after contacting this researcher (M L-C) by telephone and verbally agreeing to consider participation. The screening tool was developed with assistance from the KP Downey Medical Center discharge planners, physical therapists, orthopedic surgeon physician champion, and orthopedic NP. This group described characteristics of a successful versus unsuccessful patient after TJR surgery. This information was corroborated by the literature. Depending on patient responses to the screening tool, an interview was scheduled at least 3 weeks after surgery. At their request, 7 patients were interviewed over the phone because of transportation difficulties or work-related issues. The average time from the surgery (hip or knee) to the interview was 13 weeks, excluding the one outlier. Because of the difficulty of finding eligible patients who had not taken the TJR class, one patient who was interviewed about 2 1/2 years after surgery was included. This researcher was interested in participant perceptions of their surgical experience, not in quantifying their behavior. Therefore, the time frame for postsurgical interviews was not a significant consideration.

Patients who attended the TJR class were assigned to 1 of 2 groups on the basis of whether they had answered “yes” to at least 3 questions or “no” to at least 3 questions on the screening tool (see Sidebar: Patient Screening Tool to Determine Group Placement). During screening, patients were asked questions including if they had optimized their health before surgery, eg, by losing weight or by reducing blood sugar level if needed; and if they believed that they had realistic goals about the surgery and its outcomes. These 2 groups represented patients who had been successful with their surgery and patients who were not so successful, as identified with the patient survey. The third group, a comparison group, comprised patients who did not attend the TJR class, regardless of their responses to the survey. This third group was small and difficult to capture, because the majority of KP Downey Service Area patients attended the class. According to the Downey Service Area orthopedic NP, 70% to 80% of total hip or knee replacement patients attend the class (Lori Auman, NP; personal communication, 2011 Mar 23).a Therefore, recruitment for this third group was expanded to include other areas of Southern California, such as Baldwin Park, Orange County, and South Bay.

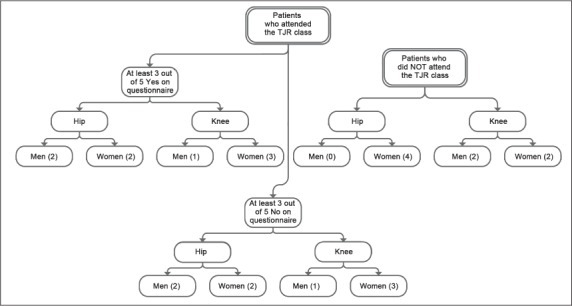

Patient screening tool to determine group placement a

Although the original design of the study was to recruit an equal number of men and women patients who had TJR surgery, early on this researcher observed that sex was not associated with perceptions. The type of joint replacement seemed to have a greater influence. This observation was supported by the literature. In the 74 studies reviewed by Ethgen and colleagues, patients who had a total hip replacement appeared to recover more functionality sooner.12 Therefore, at least 4 patients for each type of joint replacement (regardless of sex) and for each of the three constructs were interviewed. Twenty-four patients were asked to recount how they found meaning in their surgical experience. Figure 2 illustrates placement of recruited study participants.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of study participants.

TJR = total joint replacement.

Interview Method

Interviews were scheduled with eligible patients. The interview consisted of open-ended questions that allowed patients to express their views and reflections of their TJR surgery, including preparation and recovery. Probing questions were asked only to further understand patient perceptions, especially regarding decision-making ability, self-efficacy, responsibility for managing their health care, quality of life, and other means of enhancing quality of life after surgery.

Peer Review

Once the data had been analyzed, the researcher's interpretations were reviewed by the orthopedic NP. The orthopedic NP works closely with orthopedic patients before and after TJR surgery. Hence, the knowledgeable NP was able to verify patient perceptions or challenge researcher assumptions. Although triangulation is not a foolproof strategy to establish the credibility of a study, it reduces the risk of relying on only one method of data collection.13

Results

The 24 study participants explained their overall experience of TJR surgery in a variety of ways. All but 1 study participant (a woman hip-replacement patient who did not attend the class) expressed in various degrees their satisfaction with the benefits of the surgery and the need for individual responsibility. The major benefits were increasing functionality of the new joint, reduced pain, and fewer limitations in daily activities. Before surgery, a participant stated, “I felt handicapped. The pain was so intense I felt like I couldn't do anything.” One participant stated, “When I can bicycle, then I'll be back to normal.” Study participants prepared themselves mentally and physically for their surgery by a variety of methods, including the TJR class, which provided a feeling of social connectedness and stressed the importance of being independent, talking with family and friends who had already had the surgery, surfing the Internet, viewing the KP presurgical DVD, talking extensively with the orthopedic surgeon, reviewing the Krames Staywell pamphlet, and doing physical activity before the surgery. As one study participant commented, “It [the TJR class] prepares you. It wakes you up to more or less what you have to know to prepare yourself [for] the challenges.” Another person said, “… initially you feel alone going into surgery …. Once you take the class, you see so many other people going through the surgery.” Another participant noted, “Yeah, just being with a bunch of people that are going to be going through the same thing with you is very comforting.” During recovery, study participants relied on assistance from family and friends, information obtained during the TJR class, and answers provided by physical therapists.

Patient Needs

This study uncovered many different perceptions regarding patient needs. In terms of physical needs, most patients, irrespective of study category, increased their exercise after surgery rather than before surgery. This study participant's comment captured the majority of participants' feelings about exercising after surgery: “Of course, I am doing my exercise where I can lay in bed and stretch my knee. I am getting a little better …. I know it is not going to get better just lying there and watching TV.” Most were able to manage their chronic diseases both before and after surgery. However, the majority of participants had difficulty managing pain before surgery but not so much after surgery. Support from family was more prevalent than support from friends, both before and after surgery. Most study participants had a concrete support, such as a caregiver, in place before the surgery. Anxiety was predominant in those who had a knee replacement and did not attend the TJR class. Pain management issues were associated with a perception of poor quality of life and depression before and after the surgery.

Patient Education

Patient education, in the form of activities or materials accessed before or after surgery, was associated with better outcomes. As one participant noted, “Information can't hurt.” Another stated, “I mean it's very personal having your hip replaced. So I felt like I owed it to myself to be informed. You know the old saying that knowledge is power.” The materials participants used to obtain information regarding recovery were similar to those they used to prepare for surgery. The major difference was that after surgery, patients asked physical therapists questions instead of their orthopedic surgeon. A participant pointed out, “I referred to all that information that I have been given [referring to the TJR materials] several times to see if I was where I should be at that point [after surgery]. With everybody saying you're doing just great, you know, for the amount of time. It's hard to appreciate that when you're hurting.”

Patient Perspectives

Whether they attended the TJR class or not, study participants made several suggestions for improving outcomes and patient engagement during surgery preparation, hospital stay, and recovery. Their suggestions included pain management issues and post-surgical exercises to be incorporated into educational materials. Although the participants listed a variety of preferred educational methods to enhance their experience before or after surgery, the top five were, in order of preference, the TJR class, the Krames Staywell pamphlets on total hip or knee replacement surgery, the KP presurgical DVD, talking with orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists, and talking with people who had undergone TJR surgery. Many participants mentioned more than one method. As one participant stated, “I just had a lot of really neat people that kind of came into my path throughout this experience.”

Peer Review

The orthopedic NP reported that these findings corresponded to what she had observed and experienced in hospital and clinic settings. Her vast professional experience and insight into the expectations and concerns of patients undergoing TJR validated these findings.

Pain management issues were associated with a perception of poor quality of life and depression before and after the surgery.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that a multidisciplinary TJR class can foster a sense of social connectedness and independence among surgical patients undergoing total hip or knee replacement. In addition, it is important to use qualitative methods in health care research and to move forward with patient-centered rather than evidence-based medicine.

Presurgical classes promote beliefs among patients that they are not alone and that others will be undergoing similar surgical procedures. Patients are more confident in their ability to recover from surgery, with enhanced independence, if they participate in a presurgical class that provides essential information about preparing for and recovering from surgery and that (if possible) engages patients in practicing related skills before their surgery. When educational needs are met before surgery, patients are more engaged in their medical care and sense an improvement in their quality of life.

Because of the multidisciplinary character of the team that developed and taught the TJR class, which the literature supports,14–16 the study participants received consistent messages throughout their care and learned from specialty practitioners. Surgery is stressful enough without patients receiving contradictory messages from their health care team. With accurate knowledge and understanding of how to prepare for and recover from TJR, the study participants had more control over their health care.

Study participants who attended the TJR class noted that it was an integral part of their preparation and recovery from surgery. As health education budgets become tighter and budget allocations demand data-driven decision making, patient satisfaction needs consideration. Satisfied patients communicate with family members and friends about their experience, promoting growth of the Medical Group's patient base.

Lastly, patient-centered medicine, which focuses on the individual patient's concerns rather than an evidence-based process, needs to be advanced. Patient participation in health care, such as presurgical class attendance, is important. This premise is supported by the findings of this study: the TJR class provided study participants with the knowledge and skills they needed to make decisions and manage their surgical experience, leading to an enriched quality of life.

Conclusion

In the context of surgical advances, patient perspectives are sometimes neglected. The findings of this study suggest that patients' experience improved quality of life before and after surgery when an educational program encourages them to be a part of their medical team and engages them in their medical care. As Albert Schweitzer, MD, German/French philosopher and physician, is purported to have said, “Every patient carries her or his own doctor inside.” Our job as health care professionals is to release the physician within our patients.

Practice Implications

The American population is living longer with the expectation of a more active lifestyle. Additionally, TJRs are being done on a younger population because of technological advances. Therefore, research in the area of joint replacement7,8 is expanding to assist patients to return to their lifestyles sooner. In addition, as the medical field shifts from evidence-based medicine to patient-centered medicine, patients are wanting to participate more in medical decision making. Areas for further research identified by this study are pain management, methods of patient education, and success or lack of success in patients who do not take a presurgical class. The role of caregivers should also be explored.

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the technical support of Christina Christie, PhD, University of California Los Angeles Graduate School of Education and Information Studies; and the peer review support of Lori Auman, MSN, FNP, Kaiser Permanente Downey Medical Center.

Leslie E Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

a Orthopedic Nurse Practitioner, Kaiser Permanente Downey Medical Center, Downey, CA.

References

- 1.Dorr LD, Chao L. The emotional state of the patient after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007 Oct;463:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pownall E. Using a patient narrative to influence orthopaedic nursing care in fractured hips. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing. 2004 Aug;8(3):151–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Adult surgical patients and the information provided to them by nurses: a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Apr;61(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green J, Britten N. Qualitative research and evidence based medicine. BMJ. 1998 Apr 18;316(7139):1230–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conshohocken, PA: Center for Assessment and Policy Development; 2005. Evaluation tools for racial equity [monograph on the Internet] [cited 2010 May 20]. Available from: www.evaluationtoolsforracialequity.org [click on “tip sheet”] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battle Creek, MI: WK Kellog foundation; 2004 January. Logic model development guide: Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action: logical model development guide [monograph on the Internet] [cited 2012 May 29]. Available from: www.wkkf.org/knowledge-center/resources/2006/02/WK-Kellogg-Foundation-Logic-Model-Development-Guide.aspx [click on Download Now] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensing JM, Verhaak PF, van Dulmen AM, Visser AP. Communication: the royal pathway to patient-centered medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 2000 Jan;39(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente; 2008. Total joint replacement registry [monograph on the Internet] [cited 2012 Jul 5]. Available from: http://implantregistries.kp.org/Registries/Total_Joint.htm [password protected] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch NM, Trousdale RT, Ilstrup DM. Complications after concomitant bilateral total knee arthroplasty in elderly patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997 Sep;72(9):799–805. doi: 10.4065/72.9.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.March LM, Cross M, Tribe KL, Lapsley H, Courtenay BG, Cross MJ, et al. Two knees or not two knees? Patient costs and outcomes following bilateral and unilateral total knee joint replacement surgery of OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004 May;12(5):400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.002. Arthritis COST Study Project Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josselson R, Lieblich A, editors. Interpreting experiences: the native study of lives, Vol 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. (editors) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004 May;86-A(5):963–74. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Second Edition. Vol 42. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adeline CYM. Patients' perspectives on the pre-operative education programme. Singapore General Hospital Proceedings. 2003;12(2):64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prouty A, Cooper M, Thomas P, et al. Multidisciplinary patient education for total joint replacement surgery patients. Orthop Nurs. 2006 Jul–Aug;25(4):257–61. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saufl N, Owens A, Kelly I, Merrill B, Freyaldenhousen LL. A multidisciplinary approach to total joint replacement. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007 Jun;22(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2007.03.007. Erratum in: J Perianesth Nurs 2007 Dec;22(6):448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]