Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs) are mobile genetic elements that encode virulence factors and depend on helper phages for their mobilization. Such mobilization is specific and depends on the ability of a phage protein to inactivate the SaPI repressor Stl. Phage 80α can mobilize several SaPIs, including SaPI1 and SaPIbov1, via its Sri and Dut proteins, respectively. In many cases, the capsids formed in the presence of the SaPI are smaller than those normally produced by the phage. Two SaPI-encoded proteins, CpmA and CpmB, are involved in this size determination process. S. aureus strain Newman contains four prophages, named φNM1 through φNM4. Phages φNM1 and φNM2 are very similar to phage 80α in the structural genes, and encode almost identical Sri proteins, while their Dut proteins are highly divergent. We show that φNM1 and φNM2 are able to mobilize both SaPI1 and SaPIbov1 and yield infectious transducing particles. The majority of the capsids formed in all cases are small, showing that both SaPIs can redirect the capsid size of both φNM1 and φNM2.

Keywords: mobile genetic elements, SaPI1, SaPIbov1, bacteriophage assembly, capsid size determination

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a ubiquitous bacterium that is associated with a variety of clinical presentations.1 The emergence of community-acquired virulent and antibiotic resistant S. aureus strains is a significant public health issue.2 Virulence in S. aureus and other bacteria is often associated with mobile genetic elements, such as bacteriophages, plasmids and pathogenicity islands that are horizontally transferred within the bacterial population.3,4

Bacteriophages are also involved in the mobilization of a family of S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs).5 SaPIs are 14–27 kb genetic elements that contain phage-like repressor, integrase and terminase genes, as well as genes encoding superantigen toxins and other virulence and antibiotic resistance factors. Two of the best characterized SaPIs are SaPI1 and SaPIbov1, found in S. aureus strains RN4282 and RF122, respectively.5 SaPI1 carries genes for the toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (tst) and enterotoxins K (sek) and Q (seq).6 SaPIbov1 carries tst as well as sec and sel, encoding enterotoxins C and L, respectively, and is associated with bovine pathogenic S. aureus.7 While normally repressed and stably integrated in the host genome, SaPIs become derepressed and mobilized by specific “helper” bacteriophages. Upon mobilization, the SaPI genomes are packaged into transducing particles formed by structural proteins encoded by the helper phage.8,9

The first step of the mobilization process is the inactivation of the SaPI Stl repressor, which is dependent on specific interactions between Stl and a phage-encoded derepressor.5,10 Bacteriophage 80α, a transducing phage that is closely related to staphylococcal typing phage 53,11-13 encodes a protein, Sri, gene product (gp) of open reading frame (orf) 2211(Table 1) that binds to and deactivates SaPI1 Stl. In contrast, the SaPIbov1 Stl protein, which only shares 16% sequence identity with SaPI1 Stl, does not respond to Sri. Instead, SaPIbov1 Stl is inactivated by binding of 80α gp32 (Table 2), which encodes a dUTPase (Dut).10 A third mechanism is found in SaPIbov2, in which Stl is derepressed by the 80α gp15 protein.10 80α has also been shown to derepress SaPI2 and SaPIn1, by an unknown mechanism.5 Derepression leads to excision and replication of the SaPI genome.

Table 1. Genes and gene products in 80α, φNM1 and φNM2.

| 80α ORF |

Protein name |

GenBank identifiers |

Function |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80α | φNM1 | φNM2 | |||

| 1 |

Int |

ABF71572 |

ABF73031 |

ABF73095 |

Integrase |

| 6 |

CI |

ABF71577 |

ABF73035 |

ABF73098 |

CI-like repressor |

| 22 |

Sri |

ABF71593 |

* |

ABF73115 |

Anti-repressor of SaPI1 Stl |

| 32 |

Dut |

ABF71603 |

ABF73061 |

ABF73127 |

dUTPase; anti-repressor of SaPIbov1 Stl |

| 40 |

TerS |

ABF71611 |

ABF73067 |

ABF73133 |

Small terminase subunit |

| 41 |

TerL |

ABF71612 |

ABF73068 |

ABF73134 |

Large terminase subunit |

| 42 |

PP |

ABF71613 |

ABF73069 |

ABF73135 |

Portal protein |

| 44 |

gp44 |

ABF71615 |

ABF73070 |

ABF73136 |

minor capsid protein |

| 46 |

SP |

ABF71617 |

ABF73072 |

ABF73138 |

Scaffolding protein |

| 47 |

CP |

ABF71619 |

ABF73073 |

ABF73139 |

Major capsid protein |

| 53 |

TP |

ABF71624 |

ABF73079 |

ABF73145 |

Major tail protein |

| 70 |

Hol |

ABF71641 |

ABF73093 |

ABF73159 |

Holin; cell lysis |

| 71 | Lyt | ABF71642 | ABF73094 | ABF73160 | Lysin; amidase; cell lysis |

Table 2. Genes and gene products in SaPI1 (GenBank ID U93688) and SaPIbov1 (AF217235).

Capsid assembly in 80α, as in other bacteriophages, starts with the formation of a precursor procapsid from the major capsid protein (CP; gp47 in 80α) and a scaffolding protein (SP; gp46)11 that acts as a chaperone for the assembly process.14,15 A ring-shaped portal made of portal protein (PP; gp42) and a few copies of a minor protein of unknown function (gp44), are also incorporated into the procapsid.8,16 The DNA is packaged through the portal in a process that requires the terminase complex, consisting of the small (TerS; gp40) and large (TerL; gp41) terminase subunits. During DNA packaging, the capsid changes from a round, thick-walled procapsid to an angular, thin-walled mature capsid.17

A unique aspect of the phage-induced SaPI mobilization is that in many cases, the capsids formed are smaller (having T = 4 icosahedral symmetry18) than those normally formed by the phage alone17 (T = 7). The smaller capsid can only accommodate the smaller SaPI genome and thus interferes with phage multiplication.6 We previously showed that SaPI1 proteins gp6 (CpmB, Capsid morphogenesis protein B) and gp7 (CpmA) (corresponding to SaPIbov1 gp8 and gp9, respectively; Table 2) are involved in this size determination,16,18-20 and that CpmB acts as an internal scaffold in the T = 4 SaPI1 procapsids.18 CpmA and CpmB are conserved, and always appear together, in the majority of SaPIs sequenced to date.5 Other factors, including the SaPI-encoded TerS subunit, also contribute to phage interference.21,22

S. aureus strain Newman (NCTC 8178) was originally isolated from a case of ‘secondarily infected tubercular osteomyelitis’23. It produces more coagulase than other strains23 and is currently used in animal infection models.24-27 The strain Newman genome28 (GenBank ID AP009351) contains no recognizable SaPIs, but harbors four prophages, named φNM1, φNM2, φNM3 and φNM4,29 three of which (φNM1, φNM2 and φNM4) could be induced via the SOS response with mitomycin C, and one (φNM3), that could not. A phage-cured strain Newman showed greatly reduced virulence, largely due to the lack of φNM3, which carries several virulence genes, but the other phages also appear to contribute to the parental strain’s virulence.29

Based on sequence comparisons with 80α, we predicted that φNM1 and φNM2 should be able to mobilize SaPI1 and other SaPIs that are mobilized by the 80α Sri protein. In this paper, we test this prediction, and find that φNM1 and φNM2 can indeed mobilize SaPI1. In addition, both phages can mobilize SaPIbov1, which was surprising, in light of the extreme differences in the Dut protein. We also find that φNM1 and φNM2 respond to capsid size determination induced by SaPI1 and SaPIbov1, although in the case of mobilization of SaPIbov1 by 80α, only about 63% of the capsids formed are small. Our results suggest that prophages found in clinical isolates of S. aureus may play a role in mobilization, spread and establishment of pathogenicity islands in the bacterial population, and underscore the importance of prophages in the evolution of bacterial pathogenicity.

Results and Discussion

Sequences of Newman phages φNM1 and φNM2

S. aureus strain Newman phages φNM1 and φNM229 were identified in a global BLAST search for bacteriophage sequences related to the 80α CP and SP. The other two Newman phages, φNM3 and φNM4, are more distantly related to 80α and were not picked up by a BLAST search. The φNM4 capsid protein is about 37% identical to those of 80α, φNM1 and φNM2, while φNM3 is not homologous to the other three phages; it is non-inducible by mitomycin C and appears to be defective in excision and lysis.29 φNM3 and φNM4 will not be considered further in this paper.

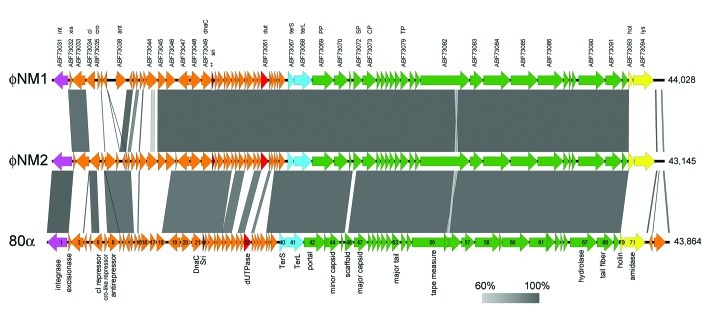

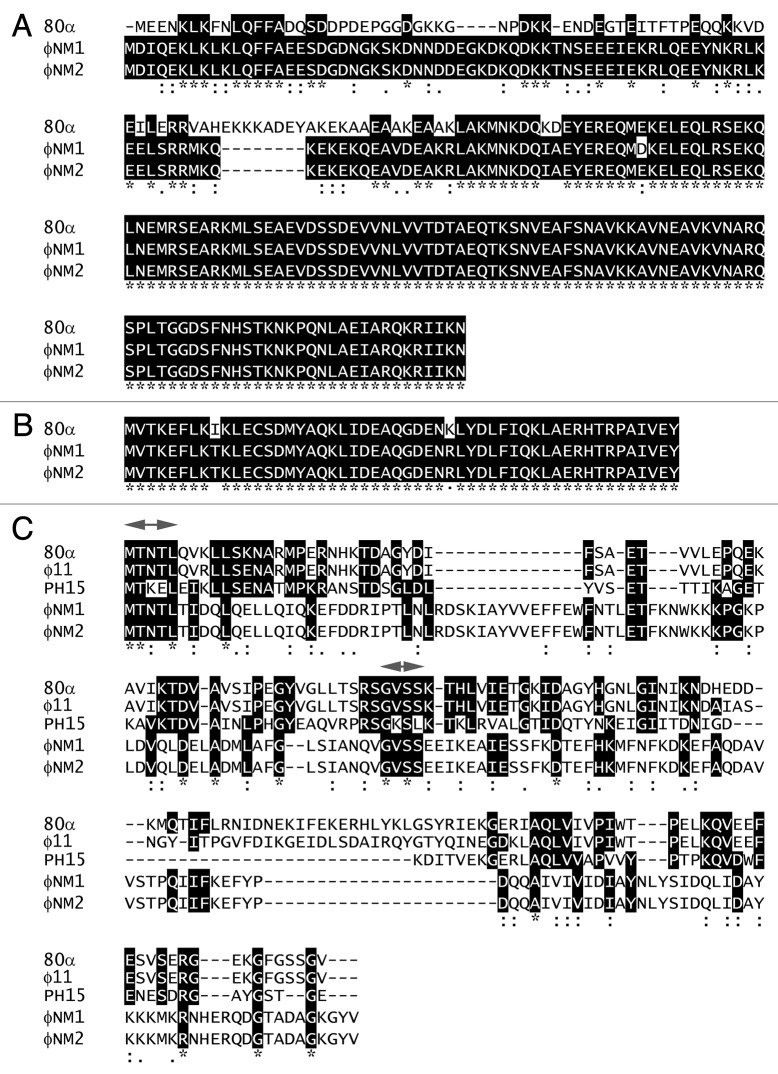

The complete genomic sequences of φNM1 (GenBank accession number DQ530359),29 φNM2 (DQ530360)29 and 80α (DQ517338)11 were aligned using the programs Easyfig30 (Fig. 1) and VISTA31 (Fig. S1). Large tracts of the three genomes are identical, in particular the structural gene cluster starting from terS [80α orf40, nucleotide (nt) number 16,407] until the end of 80α orf69 at nt 40,331 (Fig. 1), which in 80α are all considered to belong to the same operon.11 (See Table 1 for a listing of relevant proteins and their GenBank IDs.) The major capsid proteins (CP) of φNM1 and φNM2 share 99% sequence identity with 80α CP. The scaffolding proteins (SP) are 68% identical to 80α SP, with all differences clustered in the N-terminal half of the protein (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the C-terminal end of SP, which is thought to be responsible for CP binding,18 is conserved.

Figure 1. Genomic sequence alignments of φNM1 (GenBank entry DQ530359), φNM2 (DQ530360) and 80α (DQ517338), displayed using Easyfig v2.0.30 The arrows represent the ORFs annotated in the entries, whereas the shading between them represent the percentage identity (BLASTn) from 60% (light gray) to 100% (dark gray). The labels above the φNM1 sequence correspond to the protein identifiers from the GenBank file followed by the name of the protein product, where available (Table 1). The sri gene (corresponding to orf22 in 80α, which was not annotated in the φNM1 GenBank entry, is indicated with a double asterisk (**). The ORFs in 80α are numbered according to Christie et al.11 with protein functions shown below. Genes encoding structural proteins are colored green; terminase, light blue; lysis genes, yellow; integrase, magenta; Sri, dark red; Dut, light red.

Figure 2. Multiple protein sequence alignments of pertinent gene products from 80α, φNM1 and φNM2, including SP (A), Sri (B), and Dut (C). (See Table 1 for protein identifiers.) In (C), corresponding proteins from φ11 and S. epidermidis phage PH15 are also included, and the conserved MTNTL and GVSS motifs are indicated (arrows) above the alignment. Residues that are identical between three or more sequences are highlighted. Conservation between all five sequences is indicated underneath the alignment. The alignments were generated with Clustal Omega.34

Other genes were also conserved (Fig. 1), most notably the genes encoding the SaPI1 antirepressor (Sri) homologs, which exhibit only two amino acid substitutions at the protein level (Fig. 2B). 80α Sri (ABF71593) corresponds to protein ABF73115 in φNM2. In the φNM1 sequence, the equivalent gene was not annotated, but corresponds to an orf that is found between nt 11,303–11,461 (which lies between ABF73049 and ABF73050; Table 1). This similarity suggested that φNM1 and φNM2 should be able to derepress SaPI1 by the same mechanism previously determined for 80α.10 Indeed, φNM2 (and φNM4) were previously shown to mobilize SaPI1.32

The divergent regions of the sequences include numerous orfs that are comparable in size and location to genes in 80α, but are non-homologous. One such gene is 80α orf32, which encodes the Dut antirepressor (ABF71603) of SaPIbov1 Stl.10 According to its position in the genome, this gene corresponds to proteins ABF73061 in φNM1 and ABF73127 in φNM2 (Table 1). While these proteins are identical between φNM1 and φNM2, they share less than 15% sequence identity with 80α Dut (Fig. 2C).

Differences between φNM1 and φNM2 are localized to the two ends of the genome. The integrase (int) gene, at the leftmost end of the sequence, is similar between 80α and φNM2, but differs in φNM1 (Fig. 1). A corresponding relationship is found in the attachment (att) sites, which are recognized by the integrase.9 At the opposite end of the genome, the lysis genes (holin and lysin; φNM1 proteins ABF73093 and ABF73094, respectively) are similar in 80α and φNM1, but differ in φNM2 (Fig. S1).

Mobilization of SaPIs by φNM1 and φNM2

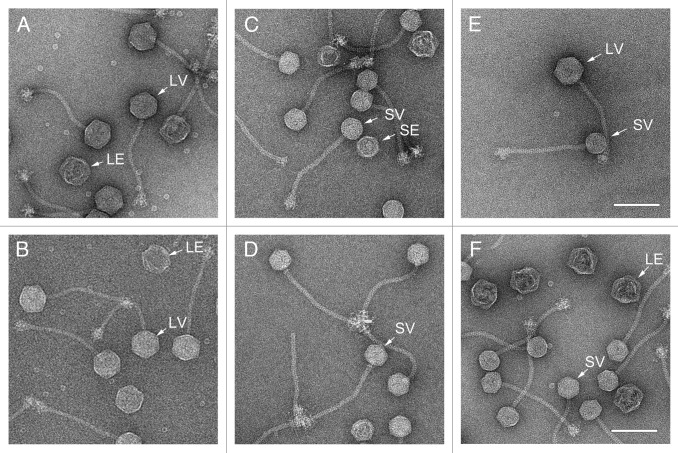

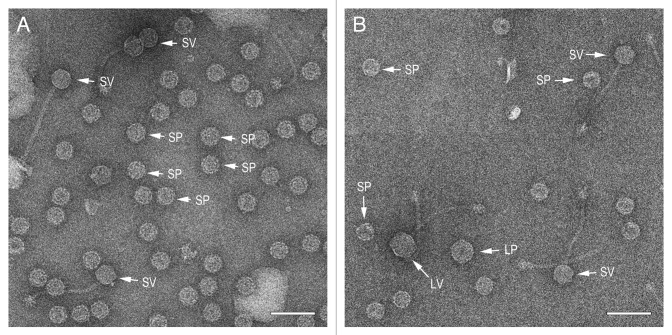

S. aureus strains TB25 and TB26 contain phages φNM1 and φNM2, respectively, lysogenized in the phage-cured S. aureus strain RN45029 (Table 3). RN10616 is an 80α lysogen.22 The lysogens were induced with mitomycin C, and the resulting lysates were purified by PEG precipitation and CsCl density gradient separation, as previously described.16 The purified φNM1 and φNM2 fractions were analyzed for the presence of phage particles by electron microscopy (EM). Both contained siphoviruses with 60 nm diameter icosahedral capsids and 185 nm tails (Fig. 3A,B), similar to those of phage 80α,16,17 and consistent with the previous report,29 except that we did not observe a difference in tail length between φNM1 and φNM2.

Table 3. List of S. aureus strains used in this study and the prophages and SaPIs contained within them.

| Strain | Genotype | Phage | SaPI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RN450 |

phage-cured version of S. aureus strain RN1 (NCTC8325) |

– |

– |

Novick 1967,12 Novick 199133 |

| RN4220 |

Transformable mutant of RN450 |

– |

– |

Kreiswirth et al. 1983,35 Novick 199133 |

| RN10616 |

RN4220(80α) |

80α |

– |

Ubeda et al. 200922 |

| TB25 |

RN450(φNM1) |

φNM1 |

– |

Bae et al. 200629 |

| TB26 |

RN450(φNM2) |

φNM2 |

– |

Bae et al. 200629 |

| ST1* |

RN4220(SaPI1) |

– |

SaPI1 tst::tetM |

Christie et al. 201011 |

| RN10628 |

RN4220(SaPI1, 80α) |

80α |

SaPI1 tst::tetM |

Ubeda et al. 200922 |

| ST137 |

RN4220(SaPIbov1) |

– |

SaPIbov1 tst::tetM |

G.E. Christie, unpublished |

| AD1 |

TB25(SaPI1) |

φNM1 |

SaPI1 tst::tetM |

this work |

| AD2 |

TB26(SaPI1) |

φNM2 |

SaPI1 tst::tetM |

this work |

| AD3 |

TB25(SaPIbov1) |

φNM1 |

SaPIbov1 tst::tetM |

this work |

| AD4 |

TB26(SaPIbov1) |

φNM2 |

SaPIbov1 tst::tetM |

this work |

| AD5 | RN10616(SaPIbov1) | 80α | SaPIbov1 tst::tetM | this work |

Independent isolate, equivalent to strain RN10822.11

Figure 3. Electron micrographs of negatively stained, CsCl gradient-purified formed by induction of the φNM1 lysogen TB25 (A) and the φNM2 lysogen TB26 (B). Negatively stained transducing particles formed by mobilization of SaPI1 with φNM1 (C) and φNM2 (D), and by mobilization of SaPIbov1 with φNM1 (E) and φNM2 (F). Examples of small virions (SV), large virions (LV) and large empty capsids (LE) are indicated. Scale bars equal 100 nm.

The crude lysates from the phage inductions above were filtered through a 0.22 µm filter to remove unlysed cells. The filtrates were used to infect S. aureus strain ST1, an RN4220 derivative that contains SaPI1 tst::tetM (Table 3). At 2–3 h post infection, unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation, and the resulting particles were purified as described above. EM revealed siphovirus particles similar to the phages, but having predominantly smaller (~45 nm) capsids (Fig. 3 C and D). This result shows that, like 80α, φNM1 and φNM2 both respond to the previously described SaP1-induced size determination.6

To test for the ability to transduce S. aureus, the 0.22 µm filtered lysates from the ST1 infections were mixed with S. aureus strain RN4220 and plated out on GL agar containing 5 µg/ml tetracycline. In all three cases (ST1 infected by 80α, φNM1 and φNM2), the lysates successfully conferred tetracycline resistance on RN4220, showing that the particles had been packaged with the SaPI1 tst::tetM genome (Table 4). PCR with primers specific to SaPI1 orf618 also confirmed that SaPI1 DNA was present in all three transductants (data not shown).

Table 4. Transducing titers (c.f.u./ml) for infections of SaPI-containing strains by phages 80α, φNM1 and φNM2. Numbers for ST1 are an average of three technical replicates.

| |

Infecting phage |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient strain | 80α | φNM1 | φNM2 |

| ST1 (SaPI1) |

2.7 × 108 (1)* |

2.0 × 109 (7.4) |

6.0 × 108 (2.2) |

| ST137 (SaPIbov1) | 1.9 × 108 (1) | 3.4 × 108 (1.8) | 3.2 × 108 (1.7) |

Numbers in parentheses were normalized to 80α for each SaPI.

To test for mobilization of SaPIbov1, the filtered φNM1 and φNM2 phage lysates were used to infect ST137, which is an RN4220 derivative containing SaPIbov1 tst::tetM (Table 3) (G.E. Christie, unpublished data). As a positive control, the cells were infected with an 80α lysate in parallel. The resulting lysates were purified and analyzed by EM. Both large and small capsids were observed (Fig. 3E and F). Aliquots of 0.22 µm filtered lysates from the ST137 infections were used to infect RN4220. The φNM1 and φNM2 lysates were as efficient as 80α in conferring tetracycline resistance on RN4220 (Table 4). These results show that SaPIbov1 tst::tetM DNA had been successfully mobilized by both φNM1 and φNM2 and packaged into transducing particles, in spite of the lack of a recognizable Dut protein.

The only substantial sequence homology between 80α Dut and the corresponding proteins in φNM1 and φNM2 are two short, completely conserved motifs: an N-terminal MTNTL sequence and an internal GVSS sequence (Fig. 2C). These motifs are outside of the middle region that is divergent between 80α and φ11 Dut, and that was previously shown to affect the rate of mobilization.10 In S. epidermidis phage PH15, which does not induce SaPIbov1,10 the MTNTL and GVSS motifs are not completely conserved, in spite of otherwise relatively high sequence conservation (40% identity; Figure 2C). Thus, the ability to bind Stl and mobilize SaPIbov1 might depend on these motifs. Alternatively, another factor encoded by φNM1 and φNM2 could be able to carry out the SaPIbov1 derepression.

Although only Dut has a known activity other than Stl derepression (as a dUTPase), Sri and other derepressor proteins are also assumed to serve some phage function, since the ability to mobilize a SaPI would seem to offer no benefit to the phage. Apparently, the SaPIs have evolved the ability to use these proteins to sense when an appropriate phage enters the lytic cycle and use this otherwise terminal event to their advantage.10

Capsid size determination

Double lysogens containing a φNM1 or φNM2 and SaPI1 or SaPIbov1 were made by introducing filtered lysates of SaPI1 tst::tetM or SaPIbov1 tst::tetM into TB25 and TB26, and selecting for tetracycline resistance, yielding strains AD1 (φNM1, SaPI1), AD2 (φNM2, SaPI1), AD3 (φNM1, SaPIbov1) and AD4 (φNM2, SaPI1bov1) (Table 3). A double lysogen of 80α and SaPIbov1 was made by introducing SaPIbov1 tst::tetM into the 80α lysogen RN10616,22 yielding strain AD5 (80α, SaPIbov1)(Table 3). RN10628, a double lysogen of 80α and SaPI1 tst::tetM was previously described.22 The use of double lysogens instead of infections circumvents the effects of variation in m.o.i. by ensuring a 1:1 ratio of phage to SaPI genomes. To eliminate the possibility of contamination from another helper phage, we used SaPI1 and SaPIbov1 lysates prepared with the same helper phage with which we made the double lysogens.

The resulting transductants were grown under tetracycline selection and induced with mitomycin C as previously described.16 Lysis for φNM1 and 80α occurred after about 4 h. The φNM2-containing double lysogens did not obviously lyse, but the supernatant was collected after 4 h and purified the same way as the other lysates. Unlysed cells were removed in the first centrifugation step. The difference in lysis for φNM2 could be related to the differences in the lytic proteins, holin and lysin (Fig. 1).

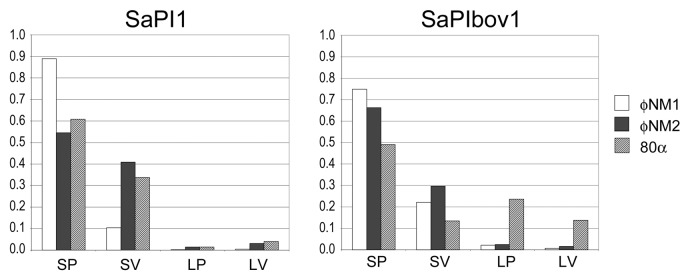

To avoid the separation of different types of particles (procapsids, mature capsids, empty mature capsids) into different fractions that is inherent in the CsCl gradient purification, these particles were purified only by PEG precipitation and differential centrifugation, and imaged by EM (Fig. 4). The samples were not as clean as the CsCl gradient-purified particles, but included a representative distribution of procapsids and packaged, mature transducing particles of all sizes. A minimum of 300 particles were counted and measured for each double lysogen. The capsids were divided into four groups by size (large or small) and maturity (procapsids vs. mature capsids) and plotted as a fraction of the total number of capsids (Fig. 5). As observed previously16 many mature capsids are also empty due to abortive DNA packaging or loss of DNA during purification. These are easily distinguishable from procapsids and were grouped together with the mature capsids. A small number of aberrant shells that did not fit into any of the categories above were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 4. Electron micrographs of negatively stained, partially purified lysates from the double lysogens AD1 (φNM1, SaPI1) (A) and AD5 (80α, SaPIbov1) (B). Examples of particles corresponding to small procapsids (SP), small virions (SV), large procapsids (LP) and large virions (LV) are indicated in each panel. Scale bars equal 100 nm.

Figure 5. Particle distribution histograms for the mobilization of SaPI1 and SaPIbov1 by phages φNM1 (white), φNM2 (black) and 80α (hatched). Particles were scored as small procapsids (SP), small virions (SV), large procapsids (LP) and large virions (LV) and plotted as a fraction of the total number of particles scored in each sample.

By this analysis, SaPI1 induced small capsid size equally efficiently in φNM1, φNM2 and 80α, with 90–95% small capsids formed, including procapsids and mature capsids (Fig. 5). Similarly, SaPIbov1 is equally efficient as SaPI1 in converting φNM1 and φNM2 to the small capsid phenotype: > 95% of the resulting capsids (procapsids and mature capsids) were, in both cases, small (Fig. 5). This was not surprising, in light of the high degree of similarity (99%) between the CP of 80α, φNM1 and φNM2 and the conservation of CpmA and CpmB, which are 94% and 96% identical, respectively, between SaPI1 and SaPIbov1.

When SaPIbov1 was mobilized by 80a, in contrast, only 63% of the resulting capsids were small (Figs. 4B and 5). It is unclear why this particular combination of SaPI and phage should be less efficient at size determination. It could be related to protein expression or the presence of other factors that modulate the effect of CpmA and CpmB. It is also possible that derepression of SaPIbov1 by 80α is less efficient, but the high transducing titers obtained with SaPIbov1 (Table 4) suggests that this was not the case.

In all cases, the majority of the of the capsids did not mature and remained as procapsids in the lysate. This is perhaps not surprising, as the cells may run out of energy to package DNA during the time between mitomycin C induction and lysis. The most striking example of this was φNM1, for which 90% of the capsids observed were procapsids (Fig. 4A and 5).

Formation of small particles is one of the mechanisms by which SaPIs interfere with phage multiplication. Some SaPIs lack homologs of the cpmA and cpmB genes5 and are thus presumed not to change the size of their helpers, although this has not been confirmed experimentally. Nevertheless, the high conservation of these genes in many SaPIs suggests that the size determination does confer an evolutionary advantage on the SaPIs under some circumstances. SaPI mobilization depends on a delicate interplay between phage and SaPI-encoded proteins, and SaPIs have evolved multiple strategies for usurping the gene products encoded by the phage for their own benefit. All these mechanisms contribute to the overall fitness of the SaPI element and its subsequent success and establishment in the S. aureus population.

Materials and Methods

Growth of bacteria and phages

S. aureus strains used are listed in Table 3. S. aureus lysogens were grown in CY media at 32°C as previously described.33 For induction of prophages, mitomycin C was added to 5 µg/ml at OD600 = 0.8. Cells were grown until lysis occurred, as evidenced by a drop in OD600, typically after 3–4 h. The clarified lysates were precipitated with 10% (w/v) PEG 6,000 in 0.5 M NaCl and pelleted at 8,600 g for 20 min. The pellets were resuspended in phage buffer (50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 4 mM CaCl2) and centrifuged at 8,600 g for 20 min to remove insoluble material. The resulting supernatant was either centrifuged at 250,000 g for 30 min to pellet all capsid-related structures, or purified further on CsCl gradients, in which case 0.5 g CsCl was added per ml of supernatant, followed by centrifugation for 20 h at 70,000 rpm in a Beckman NVT90 rotor. Bands were collected and dialyzed against phage buffer.

For phage-induced SaPI mobilization, 50 ml cultures of the appropriate SaPI-containing strains (ST1 or ST137) were grown at 32°C in the presence of 5 µg/ml tetracycline. At OD600 = 0.5, the cells were infected at an approximate m.o.i. = 1 with phage lysates that had been passed through a 0.22 µm filter to remove any intact cells. The supernatant was collected after 2–3 h of growth, and the resulting transducing particles were purified by PEG precipitation and CsCl gradient centrifugation as described above.

Transductions

For transduction assays, lysates from phage infections of equal volumes of ST1 or ST137 starting cultures were filtered through a 0.22 µm filter. Serial dilutions (100 µl volume) of the filtrates were mixed with an equal volume of RN4220 cells, incubated for 30 min at 32°C and spread on GL agar plates containing 5 µg/ml tetracycline. The plates were incubated at 32°C for 20 h and colonies were counted.

Double lysogens, containing both a SaPI and a prophage, were made similarly, by mixing the filtered lysates from infections of ST1 or ST137 with the appropriate recipient phage lysogen strain (TB25, TB26 or RN10616), incubating for 30 min at 32°C and spreading on GL agar plates containing 5 µg/ml tetracycline. After restreaking, single colonies were picked and grown in CY with 5 µg/ml tetracycline. For production of particles, the resulting double lysogens were grown and induced with mitomycin C as described for the phage lysogens above. Particles to be used for capsid size measurements were purified by PEG precipitation and differential centrifugation, but were not run on CsCl gradients.

Electron microscopy

The partially purified or CsCl gradient-purified material was diluted in 80α dialysis buffer (20 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2), applied to glow-discharged 400 mesh carbon-only grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences), washed with two drops of dialysis buffer, and negatively stained stained with 1% uranyl acetate. The grids were observed in an FEI Tecnai F20 electron microscope operated at 200 kV and imaged with a Gatan Ultrascan 4000 CCD camera at a typical magnification of 65,500×.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Taeok Bae at Indiana University Northwest for supplying the φNM1 and φNM2 lysogens used in this study and to Dr Gail E. Christie at Virginia Commonwealth University for supplying other strains and for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI083255.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/bacteriophage/article/20632

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/bacteriophage/article/20632

References

- 1.Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Pathogenesis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Suppl 5):S350–9. doi: 10.1086/533591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otto M. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:143–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziebuhr W, Ohlsen K, Karch H, Korhonen T, Hacker J. Evolution of bacterial pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:719–28. doi: 10.1007/s000180050018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3057–71. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR. The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:541–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruzin A, Lindsay JA, Novick RP. Molecular genetics of SaPI1--a mobile pathogenicity island in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:365–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald JR, Monday SR, Foster TJ, Bohach GA, Hartigan PJ, Meaney WJ, et al. Characterization of a putative pathogenicity island from bovine Staphylococcus aureus encoding multiple superantigens. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:63–70. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.63-70.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tallent SM, Langston TB, Moran RG, Christie GE. Transducing particles of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1 are comprised of helper phage-encoded proteins. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7520–4. doi: 10.1128/JB.00738-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tormo MA, Ferrer MD, Maiques E, Ubeda C, Selva L, Lasa I, et al. SaPI DNA is packaged in particles composed of phage proteins. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2434–40. doi: 10.1128/JB.01349-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tormo-Más MA, Mir I, Shrestha A, Tallent SM, Campoy S, Lasa I, et al. Moonlighting bacteriophage proteins derepress staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. Nature. 2010;465:779–82. doi: 10.1038/nature09065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christie GE, Matthews AM, King DG, Lane KD, Olivarez NP, Tallent SM, et al. The complete genomes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages 80 and 80α--implications for the specificity of SaPI mobilization. Virology. 2010;407:381–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick R. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology. 1967;33:155–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wentworth BB. Bacteriophage typing of the staphylococci. Bacteriol Rev. 1963;27:253–72. doi: 10.1128/br.27.3.253-272.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dokland T. Scaffolding proteins and their role in viral assembly. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:580–603. doi: 10.1007/s000180050455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fane BA, Prevelige PE., Jr. Mechanism of scaffolding-assisted viral assembly. Adv Protein Chem. 2003;64:259–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(03)01007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poliakov A, Chang JR, Spilman MS, Damle PK, Christie GE, Mobley JA, et al. Capsid size determination by Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island SaPI1 involves specific incorporation of SaPI1 proteins into procapsids. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:465–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spilman MS, Dearborn AD, Chang JR, Damle PK, Christie GE, Dokland T. A conformational switch involved in maturation of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage 80α capsids. J Mol Biol. 2011;405:863–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dearborn AD, Spilman MS, Damle PK, Chang JR, Monroe EB, Saad JS, et al. The Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island 1 protein gp6 functions as an internal scaffold during capsid size determination. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:710–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damle PK. Helper phage capsid size redirection by staphylococcal pathogenicity island SaPI1 involves internal scaffolding proteins. Ph.D. Thesis, Dept of Microbiology and Immunology, Virginia Commonwealth University 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spilman MS. Molecular piracy in the mobilization of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island 1. Ph.D. Thesis, Dept of Microbiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ubeda C, Maiques E, Barry P, Matthews A, Tormo MA, Lasa I, et al. SaPI mutations affecting replication and transfer and enabling autonomous replication in the absence of helper phage. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ubeda C, Olivarez NP, Barry P, Wang H, Kong X, Matthews A, et al. Specificity of staphylococcal phage and SaPI DNA packaging as revealed by integrase and terminase mutations. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dajcs JJ, Thibodeaux BA, Girgis DO, O’Callaghan RJ. Corneal virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in an experimental model of keratitis. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:375–82. doi: 10.1089/10445490260099656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malachowa N, Kohler PL, Schlievert PM, Chuang ON, Dunny GM, Kobayashi SD, et al. Characterization of a Staphylococcus aureus surface virulence factor that promotes resistance to oxidative killing and infectious endocarditis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:342–52. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00736-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormick CC, Caballero AR, Balzli CL, Tang A, Weeks A, O’Callaghan RJ. Diverse virulence of Staphylococcus aureus strains for the conjunctiva. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36:14–20. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.523194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Supersac G, Piémont Y, Kubina M, Prévost G, Foster TJ. Assessment of the role of gamma-toxin in experimental endophthalmitis using a hlg-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:241–51. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:300–10. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae T, Baba T, Hiramatsu K, Schneewind O. Prophages of Staphylococcus aureus Newman and their contribution to virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1035–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–10. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W273-9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Novick RP. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science. 2009;323:139–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1164783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novick RP. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:587–636. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04029-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreiswirth BN, Löfdahl S, Betley MJ, O’Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, et al. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–12. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.