Abstract

Autophagy is a mechanism used for the transport of macromolecules to the vacuole for degradation. It can be either non-selective or selective, resulting from the specific binding of target proteins to Atg8, an essential autophagy-related protein. Nine Atg8 homologs exist in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, suggesting possible different roles for different homologs. In a previous report published in the Plant Cell, our group identified two plant-specific proteins, termed ATI1 and ATI2, which bind Atg8f, as a representative of the nine Atg8 homologs. The proteins were shown to associate with novel starvation-induced bodies that move on the ER network and reach the lytic vacuole. Altered expression level of the proteins was also shown to affect the ability of seeds to germinate in the presence of the germination inhibiting hormone ABA. In the present addendum article, we demonstrate that, in addition to Atg8f, ATI1 binds Atg8h, an Atg8 homolog from a different sub-family, indicating that ATI1 is not a specific target of Atg8f.

Keywords: ATI1, Arabidopsis, Atg8, BiFC, autophagy, protein interaction

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a conserved eukaryotic mechanism, functioning in the degradation of macromolecules in the lytic organelle (vacuole in yeast and plants and lysosome in animals).1 The process was initially described in yeast to promote the bulk degradation of proteins, protein aggregates and organelles in response to starvation.1 However, in the past few years, accumulating evidence have demonstrated the existence of selective, target-specific autophagy.2,3 Target recognition for selective autophagy is facilitated by the binding of Atg8, a core protein of the autophagy mechanism, to a specific target protein.3,4 Plants contain large Atg8 protein families with nine different Atg8 isoforms in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana.5,6 The binding of the Atg8s to their protein targets occurs via an Atg8 Interacting Motif (AIM) in the target proteins.4 Though quite a lot of instances have been reported regarding the existence of selective autophagy in yeast and animals,3,4,7 very few reports of selective autophagy in plants have been published.8,9 Seeing that plants, due to their inability to move, must adapt to their surrounding more extensively than animals, we hypothesized that plants posses unique selective autophagy targets, corresponding with plant-specific processes. We therefore, set out to identify novel, plant specific Atg8 binding proteins in Arabidopsis.

In our recent report,10 we described two homologous, plant-specific proteins (At2g45980 and At4g00355), termed ATI1 and ATI2, respectively, which interact with Atg8f (At4g16520, as a representative of nine Atg8 homologs in Arabidopsis) and associate, under carbon starvation, with novel bodies (ATI1 bodies) that move dynamically on the ER network. These bodies also seem to reach the vacuole as their final destination.10 Both proteins contain two putative AIMs, flanking a predicted transmembrane domain. The interaction between the ATI1/2 and Atg8f was determined using two independent approaches, a yeast-two hybrid assay and the in vivo Bifluorescence Complementation (BiFC) approach.10,11 The ATI1/2 proteins were shown further to play a role in the hormonal regulation of seed germination, as altering their expression changed the ability of seeds to germinate in the presence of the germination inhibiting hormone abscisic acid (ABA).10

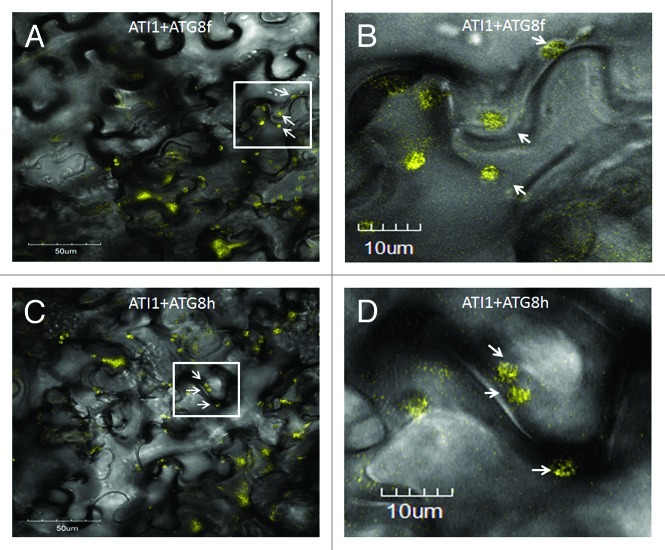

As mentioned above, nine Atg8 homologs exist in Arabidopsis.5,6 They are divided to three sub-groups according to protein sequence homology: The first subgroup contains four proteins (AtAtg8a, AtAtg8c, AtAtg8d, and AtAtg8f), the second three proteins (AtAtg8b, AtAtg8e, and AtAtg8g) and the third two proteins (AtAtg8h and AtAtg8i).5 Since AT1 and ATI2 were shown to bind Atg8f, the question arose whether they bind Atg8f specifically or can also bind a different Atg8 homolog. We therefore set out in the scope of this addendum article to examine the ability of ATI1/2 to bind Atg8h (At3g06420), an Atg8 homolog from a different subgroup than Atg8f. Atg8h is somewhat different from most other Atg8 proteins, since it possesses an exposed Gly residue essential for lipidation, and is thus not supposed to be subjected to cleavage by Atg4 as other Atg8s.6 Since both ATI1 and ATI2 posses a similar canonical AIM and display a similar cellular localization pattern,10 we focused on ATI1 as a representative. We assessed the interaction between ATI1 and Atg8h in comparison to its interaction with Atg8f, using the BiFC approach11 in which we constructed fusion proteins linking Atg8f or Atg8h with one half of the YFP protein (YFP; YN-Atg8f and YN-Atg8h) and ATI1 with the second half of the marker yellow fluorescent protein (YC-ATI1). YC-ATI1 was then co-transformed into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves with either YN-Atg8f or YN-Atg8h. In vivo interaction between ATI1 and any of these two Atg8 homologs was expected to result in YFP fluorescence, in accordance with our previous report,10 in which co-transformation of YN-Atg8f and YC-ATI1 yielded YFP fluorescence in the epidermis cells of N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 1A). In larger magnification, it could be seen that fluorescence was detected in round bodies of about 2µm in diameter (Fig. 1B – bodies marked by arrows). Interestingly, when we co-transformed YN-Atg8h with YC-ATI1 into N. benthamiana leaves we observed similar YFP fluorescence (Fig. 1C), indicating that ATI1 is capable of interacting with both Atg8f and Atg8h. In addition, under larger magnification, YFP fluorescence was observed in bodies about 2µm in diameter, similarly to Atg8f (Fig. 1D – bodies marked by arrows). This suggests that the interaction between ATI1 and both Atg8 homologs as well as the in situ cellular localization of these interactions may be similar.

Figure 1. ATI1 binds both Atg8f and atg8h. BiFC analysis including transient co-expression in N. benthamiana leaves of YC-ATI1 with either YN-Atg8f (A, B) or YN-Atg8h (C, D). YFP fluorescence, detected as yellow bodies in the cytosol (white arrows) demonstrates the interaction of ATI1 with either Atg8f or Atg8h. The images are merges transmittance and YFP fluorescence images. Panels B and D are large magnification images of the area marked by a rectangle in panels A and C, respectively.

Several Atg8 homologs exist in multi-cell animals as well as plants.13 In plants, Atg8 homologs were shown to be differentially expressed in various tissues5 and also to display different transcription patterns during nitrogen starvation,6 indicating a possible functional difference between the homologs. This is further strengthened by evidence from animals, demonstrating different roles for various Atg8 homologs in stages of autophagosome formation.14 In the case of selective autophagy, additional evidence from animals suggests that different Atg8 homologs possess different capabilities of binding selective autophagy targets.15 Taken together, one might predict ATI1 to bind only a subset of Arabidopsis Atg8 homologs, perhaps belonging to one sub-family. It is thus interesting to find that ATI1 is capable of binding both Atg8f and Atg8h, and in a similar localization pattern (Fig. 1). A possible explanation for the requirement of different Atg8 isoforms may be derived from the observation that different Arabidopsis Atg8 homologs are expressed in different plant tissues.5 It is therefore likely that interaction between ATI1 and both Atg8f and Atg8h occurs, albeit in different plant tissues. A second possibility stems from our recent finding regarding the role of ATI1/2 in seeds.10 The expression level of ATI1/2 reaches a peak in the dry seed, and we have demonstrated that altered expression level of ATI1/2 affects early seed germination in the presence of ABA.10 When examining the expression levels of both Atg8f and Atg8h in seeds, they display the same pattern as ATI1/2, demonstrating a peak of expression in the dry seed.12 This evidence may suggest the interaction of both Atg8f and Atg8h with ATI1 participate in their role during early seed germination, possibly in the transport of ABA related proteins to the lytic vacuole.10 Yet, much work is still needed in order to elucidate the differential functions of Atg8 homologs in Arabidopsis.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants from The Israel Science Foundation (Grant 764/07), the J and R Center for Scientific Research at The Weizmann Institute of Science, and the Israeli Ministry of Agriculture. G.G. is an incumbent of the Bronfman Chair of Plant Science at The Weizmann Institute of Science.

Footnotes

Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/20030

References

- 1.Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev Cell. 2009;17:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noda NN, Ohsumi Y, Inagaki F. Atg8-family interacting motif crucial for selective autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sláviková S, Shy G, Yao Y, Glozman R, Levanony H, Pietrokovski S, et al. The autophagy-associated Atg8 gene family operates both under favourable growth conditions and under starvation stresses in Arabidopsis plants. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:2839–49. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimoto K, Hanaoka H, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Noda T, et al. Processing of ATG8s, ubiquitin-like proteins, and their deconjugation by ATG4s are essential for plant autophagy. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2967–83. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, Bjørkøy G, Nunn JL, Bruun JA, et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanhee C, Zapotoczny G, Masquelier D, Ghislain M, Batoko H. The Arabidopsis multistress regulator TSPO is a heme binding membrane protein and a potential scavenger of porphyrins via an autophagy-dependent degradation mechanism. Plant Cell. 2011;23:785–805. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svenning S, Lamark T, Krause K, Johansen T. Plant NBR1 is a selective autophagy substrate and a functional hybrid of the mammalian autophagic adapters NBR1 and p62/SQSTM1. Autophagy. 2011;7:993–1010. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.16389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honig A, Avin-Wittenberg T, Ufaz S, Galili G. A new type of compartment, defined by plant-specific Atg8-interacting proteins, is induced upon exposure of Arabidopsis plants to carbon starvation. Plant Cell. 2012;24:288–303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bracha-Drori K, Shichrur K, Katz A, Oliva M, Angelovici R, Yalovsky S, et al. Detection of protein-protein interactions in plants using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 2004;40:419–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avin-Wittenberg T, Honig A, Galili G. Variations on a theme: plant autophagy in comparison to yeast and mammals. Protoplasma. 2012;249:285–99. doi: 10.1007/s00709-011-0296-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shpilka T, Weidberg H, Pietrokovski S, Elazar Z. Atg8: an autophagy-related ubiquitin-like protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12:226. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weidberg H, Shvets E, Shpilka T, Shimron F, Shinder V, Elazar Z. LC3 and GATE-16/GABARAP subfamilies are both essential yet act differently in autophagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 2010;29:1792–802. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shvets E, Abada A, Weidberg H, Elazar Z. Dissecting the involvement of LC3B and GATE-16 in p62 recruitment into autophagosomes. Autophagy. 2011;7:683–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]