Abstract

Recently we could demonstrate that FIT is post-translationally regulated in way of protein turnover and that such turnover can be counteracted by the signaling compound NO. Here we summarize findings about FIT regulation and point out which signals and post-translational modifications could act on FIT activity to regulate iron uptake from the soil.

Keywords: FIT, bHLH, ethylene, homeostasis, iron deficiency, nitric oxide, post-translational regulation, signalling, transcription factor

Plants require a battery of regulators and adaptive responses to deal with complex environmental and developmental changes. Hence, plants use hubs and bottlenecks to collect the various input signals to be able to form one common and appropriate response.1

Recent achievements in plant iron (Fe) nutrition led us to the finding that several Fe responsive bHLH proteins (BHLH038, BHLH039, BHLH100, BHLH101, POPEYE, FIT) build pillars in regulating Fe uptake in strategy I plants. The general property of bHLH proteins to build homo- and heterodimers makes this class of transcription factors a powerful tool to control the plant’s adaptation to environmental stimuli. Among the bHLH proteins related to Fe homeostasis FIT seems to have an outstanding function in controlling Fe uptake for two reasons: First, the fit knockout plants are lethal.2,3 Without FIT the Fe uptake machinery works in an inefficient manner. Second, FIT seems to function as a hub by collecting various signaling inputs deriving from the whole plant. FIT was shown to be regulated by jasmonate4 ethylene,5-8 nitric oxide,9,10 auxin,9 the circadian clock11 and Fe.2,3,8,10,12 Moreover, FIT is regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional level, so that the output of FIT can be controlled at different levels by versatile signals.2,3,8,10,12,13 Regarding the Fe deficiency signaling pathway FIT seems to act as a late gate, since it regulates the expression of IRT1 and FRO2, both, building the end of the Fe deficiency signaling transduction pathway.2,3,13-15

Here, we want to summarize recent findings concerning the regulation of FIT8,10,12 and point to putative regulatory mechanisms that might influence FIT action.

Regulation of FIT Transcript Level

The first control instance of FIT takes place at gene expression level. FIT is transcriptionally induced upon Fe deficiency.2,3 Transcription factors controlling the expression of FIT kept unidentified until now. Interestingly, we could recently demonstrate that the FIT promoter might be controlled by a transcriptional repressor.10 By using the translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) we could measure increased expression of FIT under + Fe conditions up to a level that corresponds to the – Fe situation. Due to the CHX treatment, the synthesis of this repressor might have been stopped and conclusively FIT transcription was induced. Concluding from this result, other, so far unknown regulators might favor the expression of FIT upon –Fe by removing the repressor. Interestingly, FIT itself is also suggested to act in a positive manner on its own promoter region and might thereby also promote the removal of this repressor (16; Figure 1).

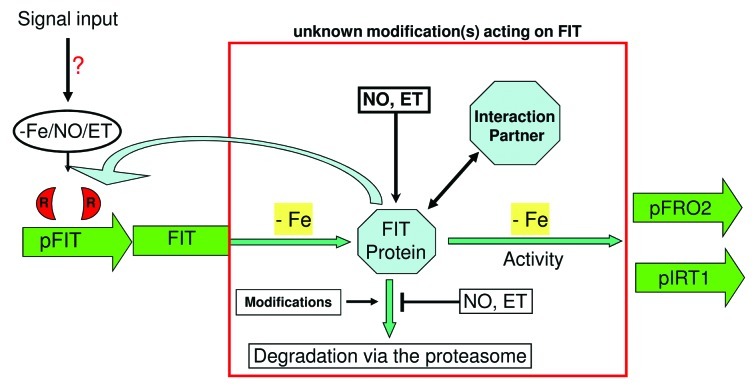

Figure 1. Regulation of FIT at transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. FIT transcription is induced upon – Fe2,3 and might be blocked at + Fe by a repressor.10 Hence, this repressor might be removed at – Fe to induce FIT transcription. A so far unknown – Fe signal as well as NO and ET could be involved in this sensing mechanism. FIT itself was also shown to act on its own transcription.16 Once FIT is transcribed, it is also translated into protein.8,10,12 To maintain exclusive induction of the target genes IRT1 and FRO2 at – Fe, FIT activity has therefore, to be regulated at post-translational level. First, this could be performed by interaction with interaction partners such as bHLH038/03913 and/or EIN3/EIL1.8 Second, NO and ET are important to maintain high FIT levels,8,10 whereas EIN3/EIL1 themselves are regulated by ET. Moreover, NO and ET are linked to each other.7 Third, degradation of FIT is controlled by the 26s proteasome and is Fe dependent.8,10,12 Post-translational modifications such as ubiquitination and putative additional other modifications could be involved in FIT degradation.

Hence, FIT transcription might be controlled by a transcriptional repression at + Fe. At – Fe the repressor might be degraded prior to induce FIT transcription.

Regulation at Post-translational Level

3-fold induction of FIT is a moderate induction in gene expression, whereas the measurable output (induction of FRO2 and IRT1) is quite high. Therefore a second instance of FIT regulation takes place at post-transcriptional level and was already proposed by Jakoby et al.3 and Colangelo and Guerinot.2 By using FIT overexpression plant lines, both groups could detect FIT mRNA at + and – Fe conditions. But, the induction of FRO2 and IRT1 was restricted to - Fe conditions, so that it was concluded that FIT must be regulated at post-transcriptional level.2,3 Recently three publications gave proof for post-translational regulation of FIT.

By using a polyclonal antibody against the c-terminal part of endogenous FIT, our group could demonstrate for the first time that FITox lines express FIT protein at + and – Fe conditions, reaching further to the assumption that FIT must be regulated at protein level to maintain the Fe dependent induction of FRO2 and IRT1.8 Moreover, Lingam et al.8 could show that high FIT protein levels rely on the presence of the ethylene (ET)-dependent transcription factors EIN3/EIL1. The Fe uptake response was compromised in the ein3/eil1 double mutant and the authors could demonstrate that FIT interacts physically with EIN3/EIL1. Subsequently, this interaction promotes FIT stability. The work unravelled a direct link between the phytohormone ET and the Fe uptake response. Thus, increased ET levels promote FIT abundance by counteracting proteasome-dependent FIT degradation which finally sustains the Fe uptake response.8

Second, in addition to ET we could demonstrate that the signaling component nitric oxide (NO) is also essential to maintain high FIT protein levels. By using HA-FIT overexpression plants we could show for the first time that NO acts at post-translational level in addition to transcriptional regulation that was demonstrated before.6,7 By using different NO scavengers we could demonstrate that HA-FIT levels dropped, indicating that the presence of NO (similar to ET) is important for high FIT protein abundance.10 Garcia et al.7 recently proposed a new model that involved ET and NO signaling in Fe uptake. The authors demonstrate that both, ET and NO can promote the production of each other and they assume that ET and NO together, generate one common output signal that directs the Fe uptake response in a positive manner.7

Work concerning FIT turnover was published independently by us10 and by Sivitz et al.16 Both groups could demonstrate, that FIT undergoes constant turnover and that high FIT protein levels are only maintained by constant resynthesis. By using CHX both groups could show that FIT levels significantly decrease, due to the blocked resynthesis. FIT turnover was shown to be Fe dependent, whereas it was pronounced upon Fe deficiency. We believe that additional yet unidentified signals are responsible to control FIT turnover. FIT degradation was shown to be likely performed by the proteasome.8,10,12 Therefore, differential turnover could be achieved for example by controlling FIT ubiquitination, which would depend on the Fe supply condition.

Due to the combined analysis of NO and ET scavengers as well as a proteasome inhibitor we could show that NO and ET counteract FIT degradation.8,10 Out of these results we can conclude that NO and ET act in a stabilizing manner on FIT whereas a second regulator must control and trigger FIT degradation. In this aspect, several scenarios are feasible. For example, turnover of FIT could be controlled by covalent modifications that regulate FIT stability and FIT activity. In addition interaction between FIT and its known interaction partners such as bHLH038/bHLH03913 and EIN3/EIL18 might control FIT degradation. However, the interaction itself could also be controlled by covalent modification on one of the two interacting proteins. In this aspect it is interesting to note that phosphorylation of EIN3 has been shown before.17 Such a phosphorylation could be mandatory for the interaction with FIT or vice versa. A mechanistic analysis of the interaction with FIT and its interaction partners would be beneficial, to explain the underlying molecular events that direct Fe uptake.

Conclusion

The recent findings shed light on the post-translational regulation of FIT. Now, the new quest is how this regulation is accomplished within the cell and how exactly this regulation looks like. Various signals have been shown to act on the regulation of FIT. A combination of both, hormonal signaling and general intracellular signaling components might act in concert to regulate Fe uptake. FIT is an important bottleneck by collecting versatile incoming signals to form one appropriate output signal. To identify signaling modules that regulate and sense the Fe uptake, in depth molecular analysis of the post-translational regulation of FIT will be important. This will help to understand the highly controlled uptake of Fe from the soil into the plant root.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- bHLH

basic helix-loop-helix

- CHX

cycloheximide

- ET

ethylene

- Fe

iron

- FIT

FER LIKE IRON DEFICIENCY INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR

- NO

nitric oxide

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/20150

References

- 1.Dietz KJ, Jacquot JP, Harris G. Hubs and bottlenecks in plant molecular signalling networks. New Phytol. 2010;188:919–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colangelo EP, Guerinot ML. The essential basic helix-loop-helix protein FIT1 is required for the iron deficiency response. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3400–12. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakoby M, Wang HY, Reidt W, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. FRU (BHLH029) is required for induction of iron mobilization genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer F, Müller S, Bauer P. Suppression of Fe deficiency gene expression by jasmonate. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49:530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romera FJ, García MJ, Alcántara E, Pérez-Vicente R. Latest findings about the interplay of auxin, ethylene and nitric oxide in the regulation of Fe deficiency responses by Strategy I plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:167–70. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García MJ, Lucena C, Romera FJ, Alcántara E, Pérez-Vicente R. Ethylene and nitric oxide involvement in the up-regulation of key genes related to iron acquisition and homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:3885–99. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García MJ, Suárez V, Romera FJ, Alcántara E, Pérez-Vicente R. A new model involving ethylene, nitric oxide and Fe to explain the regulation of Fe-acquisition genes in Strategy I plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49:537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingam S, Mohrbacher J, Brumbarova T, Potuschak T, Fink-Straube C, Blondet E, et al. Interaction between the bHLH transcription factor FIT and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3/ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE1 reveals molecular linkage between the regulation of iron acquisition and ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1815–29. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen WW, Yang JL, Qin C, Jin CW, Mo JH, Ye T, et al. Nitric oxide acts downstream of auxin to trigger root ferric-chelate reductase activity in response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:810–9. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.161109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meiser J, Lingam S, Bauer P. Posttranslational regulation of the iron deficiency basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor FIT is affected by iron and nitric oxide. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:2154–66. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.183285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vert GA, Briat JF, Curie C. Dual regulation of the Arabidopsis high-affinity root iron uptake system by local and long-distance signals. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:796–804. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivitz A, Grinvalds C, Barberon M, Curie C, Vert G. Proteasome-mediated turnover of the transcriptional activator FIT is required for plant iron-deficiency responses. Plant J. 2011;66:1044–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Y, Wu H, Wang N, Li J, Zhao W, Du J, et al. FIT interacts with AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 in regulating iron uptake gene expression for iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2008;18:385–97. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vert G, Grotz N, Dédaldéchamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat JF, et al. IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1223–33. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson NJ, Procter CM, Connolly EL, Guerinot ML. A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature. 1999;397:694–7. doi: 10.1038/17800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang HY, Klatte M, Jakoby M, Bäumlein H, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. Iron deficiency-mediated stress regulation of four subgroup Ib BHLH genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;226:897–908. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Tena G, Xiong Y, Sheen J. Dual control of nuclear EIN3 by bifurcate MAPK cascades in C2H4 signalling. Nature. 2008;451:789–95. doi: 10.1038/nature06543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]