Abstract

Autophagy plays key roles both in host defense against bacterial infection and in tumor biology. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection causes chronic gastritis and is the single most important risk factor for the development of gastric cancer in humans. Its vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) promotes gastric colonization and is associated with more severe disease. Acute exposure to VacA initially triggers host autophagy to mitigate the effects of the toxin in epithelial cells. Recently, we demonstrated that chronic exposure to VacA leads to the formation of defective autophagosomes that lack CTSD/cathepsin D and have reduced catalytic activity. Disrupted autophagy results in accumulation of reactive oxygen species and SQSTM1/p62 both in vitro and in vivo in biopsy samples from patients infected with VacA+ but not VacA- strains. We also determined that the Crohn disease susceptibility polymorphism in the essential autophagy gene ATG16L1 increases susceptibility to H. pylori infection. Furthermore, peripheral blood monocytes from individuals with the ATG16L1 risk variant show impaired autophagic responses to VacA exposure. This is the first study to identify both a host autophagy susceptibility gene for H. pylori infection and to define the mechanism by which the autophagy pathway is affected following H. pylori infection. Collectively, these findings highlight the synergistic effects of host and bacterial autophagy factors on H. pylori pathogenesis and the potential for subsequent cancer susceptibility.

Keywords: H. pylori, ATG16L1, VacA, autophagy, gastric cancer

The gram negative microaerophilic bacterium Helicobacter pylori colonizes the gastric mucosa in early childhood and, unless eradicated, causes life-long infection. H. pylori is classified as a class I carcinogen by the World Health Organization and is the etiological agent for several gastric diseases including chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and is the single most important risk factor for gastric cancer. Autophagy is a key process that modulates host inflammatory and immune responses. Numerous organisms have evolved to either evade or usurp the autophagy pathway to enhance their own survival. Autophagy has recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of the chronic inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn disease, where an inappropriate host response to enteric bacteria is thought to be involved. Genetic studies have confirmed that a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the indispensable autophagy gene ATG16L1 confers a modest but definite increased susceptibility to Crohn disease. Aberrant autophagy is also implicated in carcinogenesis. Impaired autophagy in tumors leads to accumulation of SQSTM1 and reactive oxygen species (ROS), both of which contribute to increased tumor mass. Failure of SQSTM1 degradation due to impaired autophagy is linked to tumorigenesis. We hypothesized that autophagy-related host and microbial factors contribute to both H. pylori susceptibility and aberrant autophagy responses following H. pylori infection, further increasing potential risks for gastric carcinogenesis.

H. pylori produces several virulence factors, including the vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA). This toxin enhances colonization of the gastric mucosa, promotes persistent infection and is associated with more severe disease phenotypes. Until recently, the exact mechanisms by which VacA contributes to colonization and enhanced disease remained elusive. Previously, we demonstrated that autophagy played a cytoprotective role following H. pylori infection, eliminating the VacA toxin following either acute bacterial infection or brief (6 h) direct toxin exposure. We therefore sought to investigate the effects of longer term VacA exposure on cellular autophagy responses. Prolonged VacA exposure (up to 24 h) disrupts the autophagy pathway, as evidenced by the nondegradation of the EGFP-mRFP-LC3 tandem construct in gastric epithelial cells. A progressive loss of the lysosomal enzyme CTSD from the VacA-induced autophagosomes is detected over a period of 24 h, explaining their poor degradative capacity. As a result of this impaired autophagy, increased accumulation of SQSTM1 and ROS in VacA-treated cells is observed. We also found in vivo evidence of SQSTM1 accumulation in gastric tissue sections of patients chronically infected with VacA+, but not VacA-, H. pylori strains. Furthermore, survival of VacA+H. pylori is also increased in autophagy deficient, Atg5–/– mouse embryonic fibroblasts, indicating that autophagy normally functions to restrict the growth of intracellular H. pylori.

The findings of diverse effects of acute and chronic VacA intoxication on gastric epithelial cells suggested that other host factors may act synergistically with VacA and lead to persistent infection. Host autophagy gene polymorphisms in ATG16L1 increase susceptibility to Crohn disease, and subjects harboring risk variants have impaired autophagic responses to invasive bacteria and bacterial ligands in vitro. We therefore treated peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) from genotyped volunteers with VacA toxin to determine if ATG16L1 genotype modulates the autophagic response to VacA. Interestingly, conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II is reduced in PBMCs homozygous for the risk ATG16L1*300A allele compared with those homozygous for the wild-type ATG16L1*300T allele, confirming that host ATG16L1 genotype modulates functional autophagy responses to VacA toxin. We then determined whether ATG16L1 genotype itself influences susceptibility to H. pylori infection. First-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients from Scotland as well as a German cohort were genotyped and investigated for H. pylori infection. The results clearly demonstrate a positive correlation between the presence of the ATG16L1*300A risk allele and not just H. pylori infection itself, but infection with the more toxigenic s1m1 strain of H. pylori, compared with the wild-type ATG16L1*T300 allele.

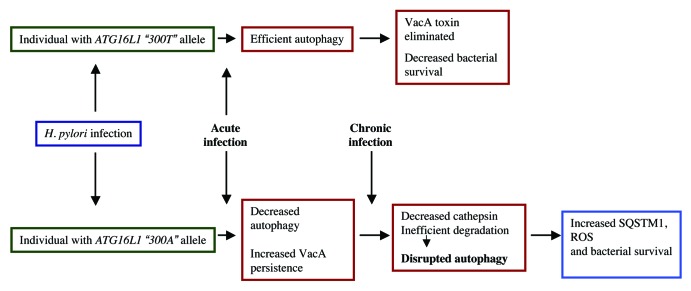

Taken together, these findings reveal that individuals carrying the risk ATG16L1*300A allele are more susceptible to H. pylori infection and have impaired autophagy responses, resulting in reduced initial autophagic clearance of the infecting bacteria. Secreted VacA toxin persists longer in these hosts, further disrupting autophagy through reduction of CTSD (Fig. 1). The resulting bacterial niche leads to chronic infection and also creates a microenvironment that may promote the development of gastric cancer. Future therapeutic strategies directed toward autophagy may help to enhance clearance of H. pylori from the gastric mucosa and possibly mitigate carcinogenesis risks.

Figure 1. Model depicting the effect of H. pylori infection in hosts with either wild-type ATG16L1 allele or the CD risk allele.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the various funding agencies that supported this study. NLJ is supported by CIHR (No. 178886) and by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/21007