Abstract

Comment on: Love IM, et al. Cell Cycle 2012; 11:2458-66.

Multiple structural, biochemical and in vivo studies have solidified the role that histone acetyltransferases (HATs) play in regulation of the p53 pathway.1 HATs are known to modulate p53 functions in many ways: from regulating its stability to promoting acetylation-dependent interactions with DNA as well as various co-factors and chromatin modifiers.1 Of these, p300, CBP, PCAF and Tip60 are the most well-studied p53 co-factors that can regulate (sometimes selectively) a number of bona fide p53 targets involved in cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA repair, metabolism and other processes.2 Of particular current interest is the time- and stress-dependent interplay between different acetyltransferases. Yet, though we now know the players, we still have only limited knowledge of their performances.

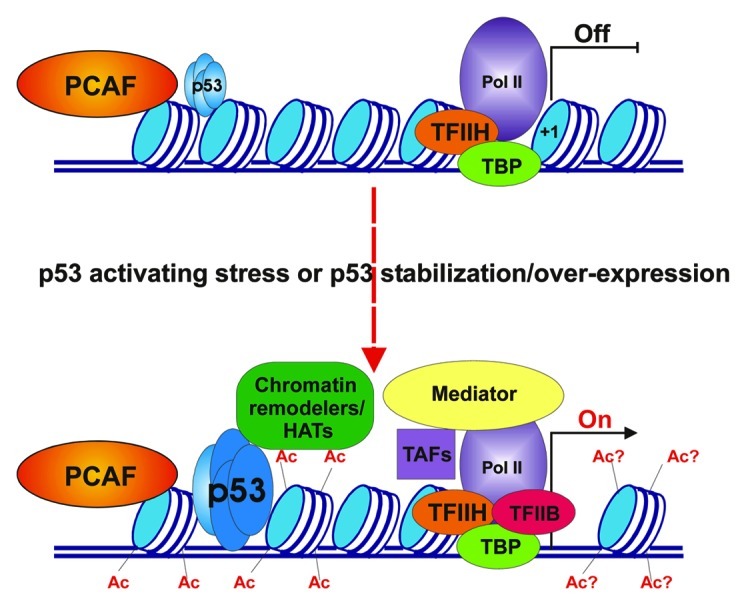

A paper by Love et al. in a previous issue of Cell Cycle, has contributed new insight into the function of one such HAT.3 Using multiple p53-activating stress conditions in combination with siRNA-mediated knockdown of specific HATs in several cancer cell lines, the authors have demonstrated the dependence of p21-driven cell cycle arrest on the histone acetyl transferase activity of PCAF. They found that PCAF, but not p300 or CBP (two closely related and well characterized transcriptional co-activators) is absolutely required for maximal p21 expression in several settings. Intriguingly, their work indicates that PCAF is exclusively important for the activation of cell cycle arrest through p53- but not Rb-dependent pathways. A pictorial description of possible events leading to p21 activation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Involvement of PCAF in p53-dependent activation of the p21 promoter. Upper panel: chromatin landscape and factors present at the p21 promoter in the absence of p53-activating stress signals. The p21 promoter is enriched with nucleosomes (blue and white cylinders) that dwell in positions proximal to the transcription start site (+1 position) and at p53 binding sites. Only low levels of p53 (represented by four miniature light blue ovals) occupy its distal and proximal binding sites. PCAF (orange oval) is present but inactive at the distal region of the p21 promoter. Some components of the transcription pre-initiation complex (PIC), including DNA-dependent Polymerase II (Pol II), TATA-binding protein (TBP) and transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) are present at the proximal promoter region near the transcription start site (TSS, shown by black vertical line) of the p21 gene. Transcription of the p21 gene is either off or very low (OFF). Lower panel: chromatin landscape and factors present at p21 promoter following p53 activating stress signals. Once levels of p53 have increased and the protein is bound to its site(s) within the p21 promoter, the PCAF complex is activated and acetylates its targets within core histones both within the distal portion of the promoter (Ac) and possibly within the TSS (Ac?). This results in the recruitment of other chromatin remodelers/modifiers, stress-specific transcription association factors (TAFs) and Mediator complex, eventually leading to active PIC formation and promoter opening (On).

Key features of the paper by Love et al. are summarized as follows. First, PCAF-dependent effects on p21 transcription are apparently unrelated to its reported MDM2-directed E3 ligase activity, which otherwise would result in subsequent elevation of p53 levels.4 Second, acetylation of a previously identified PCAF site within p53, Lys320,5 is not necessary for p21 transactivation, although the acetyl-transferase activity of PCAF, per se, is indispensable. Accordingly, previously identified PCAF sites within the H3 core histone, Lys9 and Lys14, are markedly acetylated at the strong p53 “distal” binding site within the p21 promoter following stress-induced p53 activation. Since the same lysine residues are known to be acetylated by other HATs (e.g., GCN5, SRC-1 and GCN5, p300, Tip60 and SRC-1), stress- or co-factor-dependent specificity of those modifications would need to be investigated in future studies. Finally, somewhat unexpectedly, the authors did not observe any significant changes in the levels of PCAF at the distal p53 binding site within the p21 promoter before and after p53 activation. So, it is unclear what brings PCAF to the promoter of p21 gene. Detailed analysis of the nucleosome content at that region, as reported by Laptenko et al.,6 could be informative in that regard.

Unlike the p300 and CBP HATs, human PCAF functions within a complex of more than 20 proteins.7 The acetyltransferase activity of the PCAF complex toward nucleosomal substrates is known to be markedly higher than of the PCAF enzyme itself. Several subunits within the complex show 100% identity to TAFs (TATA-binding protein-associated factors), while others are highly homologous but not identical to them. One such subunit, TAFII31 (a part of the TFIID complex), has already been shown to stabilize and activate p538; so this may provide some connection between p53-PCAF-dependent events at the distal p53 sites and the region of the promoter that is close to the start site. Finally, the largest subunit of the PCAF complex, TRAPP/PAF400, a member of the ATM super family and a component of the Tip60 HAT complex, may facilitate multiprotein assemblies (e.g., chromatin remodeling complexes) on targeted promoters .

A good scientific study, in its attempt to answer a few specific questions, inevitably generates more questions. Among those prompted by the report by Love et al. are: what brings PCAF to the p21 promoter in the absence of high levels of p53? What other subunits/activities, if any, of the PCAF complex are vital for p21 promoter activation? What PCAF-dependent changes in chromatin occur within the p21 transcription start site following stress? Future experiments will hopefully be able to address these and other questions.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21528

References

- 1.Brooks CL, et al. Protein Cell. 2011;2:456–62. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1063-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vousden KH, et al. Cell. 2009;137:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Love IM, et al. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2458–66. doi: 10.4161/cc.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linares LK, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:331–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi K, et al. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laptenko O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10385–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105680108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiltz RL, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:M37–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5154–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]