Abstract

We have previously shown that a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a biomarker of poor prognosis in breast cancers. Mechanistically, a loss of Cav-1 induces the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells, with increased autophagy/mitophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction and aerobic glycolysis. As a consequence, Cav-1-low CAFs generate nutrients (such as L-lactate) and chemical building blocks that fuel mitochondrial metabolism and the anabolic growth of adjacent breast cancer cells. It is also known that a loss of Cav-1 is associated with hyperactive TGF-β signaling. However, it remains unknown whether hyperactivation of the TGF-β signaling pathway contributes to the metabolic reprogramming of Cav-1-low CAFs. To address these issues, we overexpressed TGF-β ligands and the TGF-β receptor I (TGFβ-RI) in stromal fibroblasts and breast cancer cells. Here, we show that the role of TGF-β in tumorigenesis is compartment-specific, and that TGF-β promotes tumorigenesis by shifting cancer-associated fibroblasts toward catabolic metabolism. Importantly, the tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β are independent of the cell type generating TGF-β. Thus, stromal-derived TGF-β activates signaling in stromal cells in an autocrine fashion, leading to fibroblast activation, as judged by increased expression of myofibroblast markers, and metabolic reprogramming, with a shift toward catabolic metabolism and oxidative stress. We also show that TGF-β-activated fibroblasts promote the mitochondrial activity of adjacent cancer cells, and in a xenograft model, enhancing the growth of breast cancer cells, independently of angiogenesis. Conversely, activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not influence tumor growth, but cancer cell-derived-TGF-β ligands affect stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, leading to fibroblast activation and enhanced tumor growth. In conclusion, ligand-dependent or cell-autonomous activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells induces their metabolic reprogramming, with increased oxidative stress, autophagy/mitophagy and glycolysis, and downregulation of Cav-1. These metabolic alterations can spread among neighboring fibroblasts and greatly sustain the growth of breast cancer cells. Our data provide novel insights into the role of the TGF-β pathway in breast tumorigenesis, and establish a clear causative link between the tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β signaling and the metabolic reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: TGF beta, aerobic glycolysis, autocrine signaling, autophagy, cancer associated fibroblast, cancer metabolism, mitophagy, myofibroblast, oxidative stress, paracrine signaling, the field effect, tumor stroma, “Pied-Piper of Hamelin”

Introduction

It is well-established that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are important promoters of tumor growth, through paracrine interactions with adjacent epithelial cancer cells. These activated fibroblasts express (1) myofibroblast markers, such as α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and calponin, (2) are responsible for the accumulation and turnover of extracellular matrix components, such as collagen and tenascin C, and (3) are involved in the regulation of inflammation.1,2 Although the exact mechanism(s) that determine the acquisition of a CAF phenotype remain unknown, fibroblast activation and the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion are induced by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β).3,4 Consistent with these observations, increased expression of the TGF-β ligand is correlated with the accumulation of fibrotic desmoplastic tissue in human cancers.5

Three TGF-β ligands have been described: TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3. They are secreted as latent precursor molecules. Once activated through proteolytic cleavage, TGF-β interacts with specific receptors (namely, TGFβ receptor type I and II, known as TGFβ-RI and TGFβ-RII). TGF-β binds to TGFβ-RII, and promotes the formation of a hetero-oligomeric complex with TGFβ-RI, leading to the activation of the TGFβ-RI receptor kinase. TGFβ-RI then phosphorylates serine/threonine residues in downstream target effectors, such as the Smad proteins. The activated TGF-β receptor complex initiates several downstream cascades, including the canonical Smad2/3 signaling pathway and non-canonical pathways, such as TAK1-mediated p38- or JNK-signaling.6,7

TGF-β signaling has been implicated in tumorigenesis in several organ systems, including the breast. TGF-β plays a dual role during tumorigenesis, and it is believed to act as a tumor-suppressor during tumor initiation but as a tumor-promoter during cancer progression and metastasis.8,9 Mechanistically, the tumor-suppressor role of TGF-β has been attributed to its induction of a cyto-static response involving the upregulation of CDK inhibitors, such as p21(WAF1/CIP1) and p15(INK4B),10,11 as well as to its pro-apoptotic function(s), with the activation of cell-death pathways.12 Importantly, it is believed that most of the tumor-suppressor functions are mediated via the Smad-signaling cascade.13 Consistent with a tumor-suppressor role, inactivating mutations in key genes along the TGF-β pathways are observed in several human tumor types.14

However, aggressive tumors acquire the ability to suppress the tumor-inhibitory functions of TGF-β signaling and benefit from its pro-tumorigenic properties. Among others, TGF-β potently suppresses immunity,15 induces angiogenesis16,17 and promotes cancer cell motility and invasion by stimulating an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).18

We and others have demonstrated that a loss of stromal caveolin-1 (Cav-1) is a powerful biomarker, which predicts poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers.19,20 Analysis of Cav-1-deficient human and mouse stromal cells has demonstrated that a loss of Cav-1 is sufficient to induce a CAF-like phenotype.21-23 For example, Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fibroblasts exhibit a CAF phenotype characterized by the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and enhanced TGF-β signaling.24 Several studies have shown that Cav-1 directly inhibits TGF-β signaling. More specifically, Cav-1 interacts with the TGFβ-RI, inducing its degradation, and suppresses TGF-β-dependent Smad2 phosphorylation and its nuclear translocation.25,26 It is also known that activation of the TGF-β pathway is sufficient to downregulate Cav-1 expression27 by unknown mechanisms.

Using an established co-culture system consisting of (1) MCF7 breast cancer cells and (2) hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts, we have previously demonstrated that cancer cells induce the functional activation of fibroblasts via oxidative stress via upregulation of TGF-β signaling and loss of Cav-1 expression.23 Functionally, a loss of stromal Cav-1 causes the metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts, with the induction of autophagy and aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) in stromal cells, resulting in the stromal production of energy-rich metabolites (such as L-lactate, pyruvate, ketone bodies) and chemical building blocks [such as aminoacids (glutamine), nucleotides and fatty acids].28,29 These recycled nutrients are then transferred to adjacent epithelial cancer cells, fueling tumor growth in a paracrine fashion. Importantly, cancer-cell-initiated oxidative stress induces a loss of stromal Cav-1 in fibroblasts via autophagy and leads to the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α) in the tumor microenvironment.30,31 We have termed this new paradigm “two-compartment tumor metabolism.”29

However, it remains unknown if the activation of TGF-β signaling plays a direct role in the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells induced by a loss of Cav-1. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess if TGF-β induces specific metabolic alterations in the tumor microenvironment, and if these changes can drive the aggressive behavior of the malignant cells. To study the cell type- and compartment-specific effects of TGF-β expression, TGF-β [ligand(s) or receptor(s)] were selectively overexpressed in either fibroblasts or breast cancer cells.

For recent reviews on TGF-β signaling and tumor growth, please see references 8 and 32–36.

Results

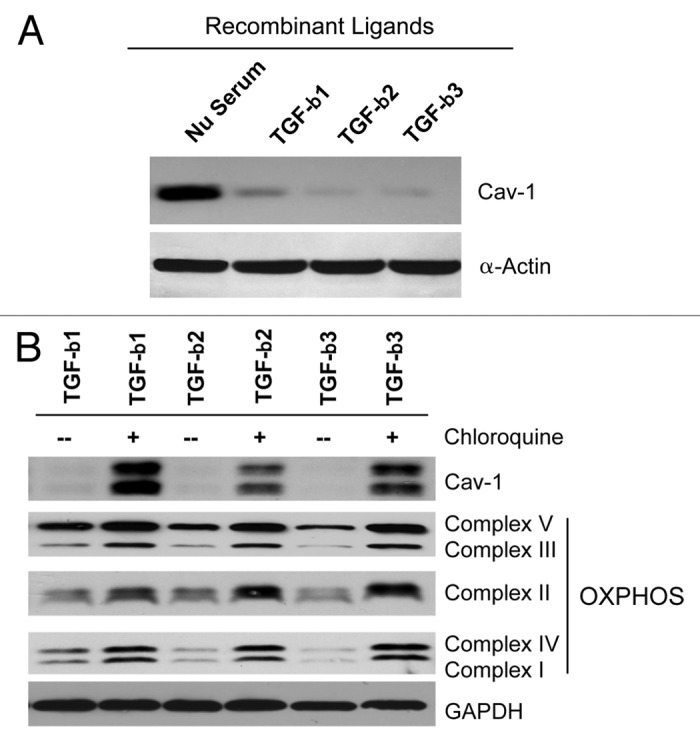

Treatment with exogenous TGF-β ligands induces Cav-1 downregulation in normal fibroblasts via lysosomal targeting and autophagic degradation

Previous studies have shown that Cav-1 negatively regulates the activation of the TGF-β signaling.25 It is also known that a loss of stromal Cav-1 induces mitochondrial dysfunction and the metabolic reprogramming of CAFs toward a more glycolytic phenotype.37,38 However, it remains unknown if enhanced TGF-β signaling is involved in the metabolic alterations observed in fibroblasts lacking Cav-1. To address this issue, hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 recombinant ligands (10 ng/ml) for 48 h. Figure 1A shows that treatment with these exogenous TGF-β ligands induces the downregulation of Cav-1 protein in stromal fibroblasts.

Figure 1. TGF-β treatment induces the autophagy-mediated downregulation of Cav-1 in fibroblasts. (A) hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts were treated with TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 (10 ng/ml) for 48 h. Then, cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Cav-1 antibodies. Note that TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 ligand treatment induces Cav-1 downregulation. β-actin was used as an equal loading control. (B) Chloroquine treatment rescues the expression of Cav-1 and OXPHOS markers. Fibroblasts treated with the three TGF-β ligands were incubated with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (25 μM) for 24 h, and then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies directed against Cav-1 and OXPHOS. Note that treatment with chloroquine rescues the expression of Cav-1 and greatly augments the levels of OXPHOS markers. Immunoblotting with GAPDH is shown as a control for equal loading.

We have previously demonstrated that a loss of stromal Cav-1 occurs via autophagy.31 Thus, TGF-β1-, TGF-β2- or TGF-β3-treated fibroblasts were next co-incubated with the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (25 μM) for 24 h. Interestingly, Figure 1B shows that chloroquine treatment restores Cav-1 levels. As a loss of stromal Cav-1 is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction,37 we also evaluated if restoration of Cav-1 levels correlates with improved mitochondrial function via immunoblot analysis with markers of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Interestingly, Figure 1B shows that chloroquine treatment greatly augments the levels of OXPHOS markers.

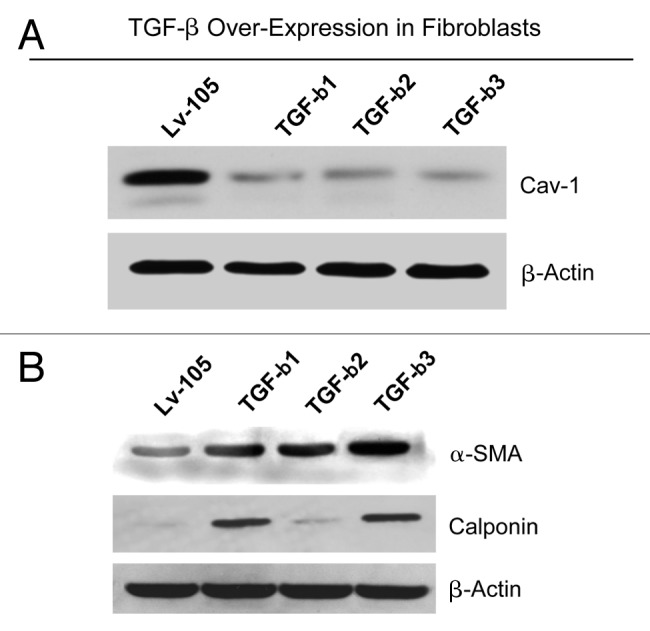

Fibroblasts recombinantly expressing TGF-β ligands upregulate markers of myofibroblast differentiation, and show a loss of Cav-1 expression

To further dissect the role of TGF-β signaling in cancer metabolism, we first stably overexpressed TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 ligands in hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts. Empty vector (Lv-105) control fibroblasts were generated in parallel. Immunoblot analysis demonstrates that all three TGF-β isoforms greatly downregulate Cav-1 levels (Fig. 2A). It is well known that TGF-β induces the activated myofibroblast phenotype.39 Martinez et al. have also shown that a loss of Cav-1 is sufficient to promote a fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion.23 Thus, we next investigated whether fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 show myofibroblastic features.

Figure 2. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 show a fibroblast to myofibroblast conversion, with Cav-1 downregulation. (A) hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts, stably expressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 or the empty vector (Lv-105) control, were generated using a lentiviral approach. After selection with puromycin, the cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Cav-1 antibodies. Note that the stable overexpression of TGF-β ligands downregulates Cav-1 protein expression. β-actin was used as an equal loading control. (B) Cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies directed against myofibroblast markers. Note that α-SMA and calponin levels are upregulated. β-actin was used as an equal loading control.

Figure 2B demonstrates that fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands all display the upregulation of myofibroblast markers, such as α-SMA and calponin. Taken together, these data demonstrate that TGF-β signaling negatively modulates Cav-1 expression and contributes to the acquisition of a myofibroblast phenotype, as expected.

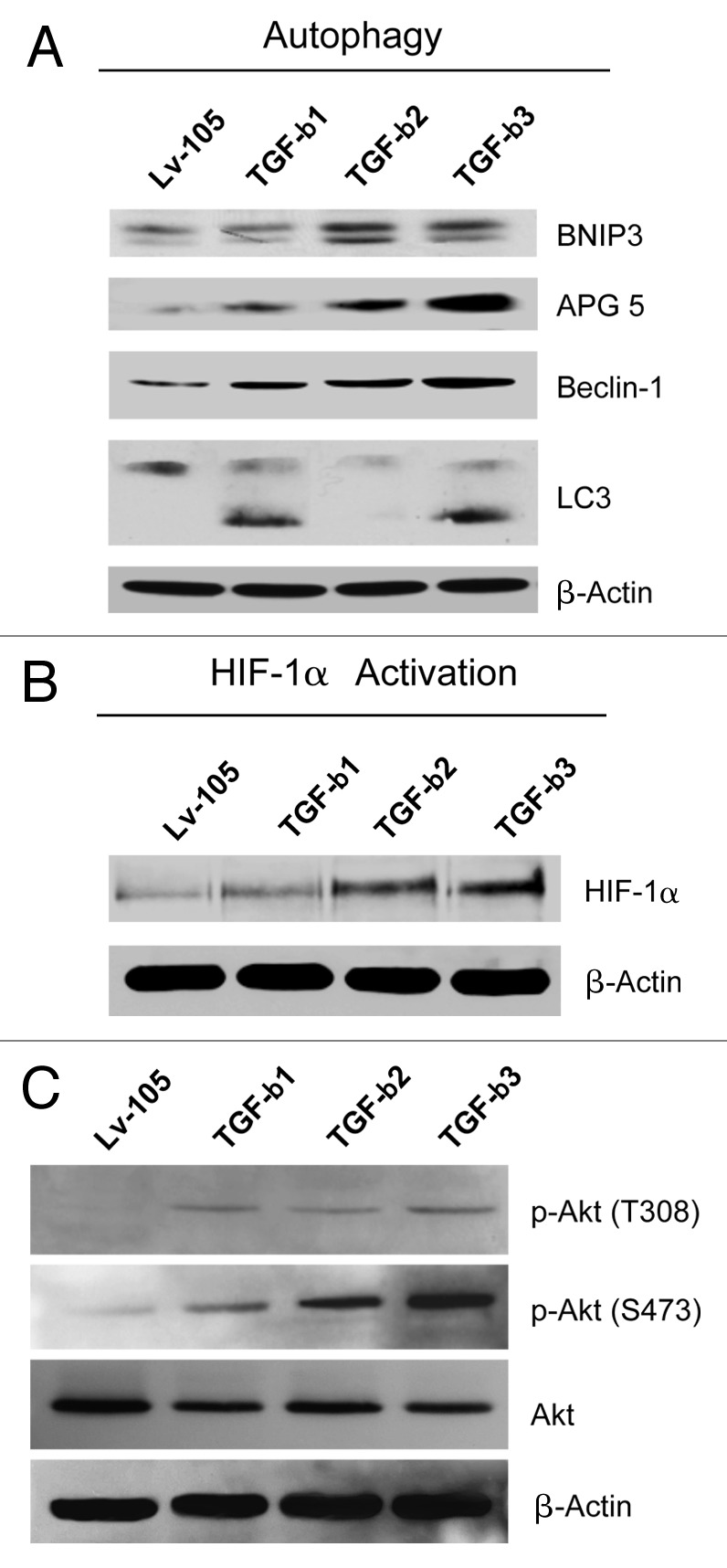

Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands show increased autophagy/mitophagy, with HIF-1α activation

Loss of stromal Cav-1 is a novel biomarker associated with tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancers.19,20 Importantly, Cav-1 downregulation leads to altered metabolic processes in CAFs, with increased autophagy, mitophagy and aerobic glycolysis.40 However, the role of TGF-β in regulating CAF metabolism remains largely unexplored. Thus, we subjected TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts to a detailed metabolic analysis. Figure 3A shows that fibroblasts expressing TGF-β ligands display increased levels of a panel of mitophagy (BNIP3; indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction) and autophagy markers (APG5, LC3 and Beclin-1; markers of the formation and maturation of auto-phagosomes) relative to vector-alone control cells.

Figure 3. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 show increased autophagy, with HIF-1α activation. (A) TGF-β-induced autophagy/mitophagy was evaluated by immunoblot analysis. TGF-β1-, TGF-β2- and TGF-β3-overexpressing fibroblasts display a significant increase of the expression of the mitophagy (BNIP3) and autophagy markers [APG5, Beclin-1, and LC3II (lower band)]. Note that TGF-β2 is able to induce upregulation of APG5 and Beclin-1, but it does not affect LC3 activation. β-actin was used as loading control. (B and C) To evaluate if TGF-β induces activation of HIF-1α and the Akt pathway, cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies directed against HIF-1α or phospho-Akt. β-actin was used as loading control. Note that TGF-β1-, TGF-β2- and TGF-β3-overexpressing fibroblasts display a significant increase of HIF-1α expression (B), and increased phospho-Akt, with decreased total Akt levels (C).

To evaluate the molecular drivers leading to increased autophagy, we next analyzed the expression of HIF-1α by immunoblotting. HIF-1α is a transcription factor mediating the cellular response to hypoxia and oxidative stress and is one of the main inducers of autophagy.41Figure 3B shows that fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands display the steady-state upregulation of HIF-1α protein levels. These results indicate that the induction of autophagy and mitophagy in fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands is mediated, at least in part, via HIF-1α activation.

It is known that increased autophagy may lead to a compensatory activation the Akt-mTOR pathway.42,43 Thus, TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 fibroblasts were subjected to immunoblot analysis with phospho-specific Akt antibodies. Figure 3C shows that TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 fibroblasts all display increased activation of the Akt pathway relative to control cells, most likely to counter-balance the increased protein degradation that occurs during autophagy.

TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts show decreased mitochondrial activity

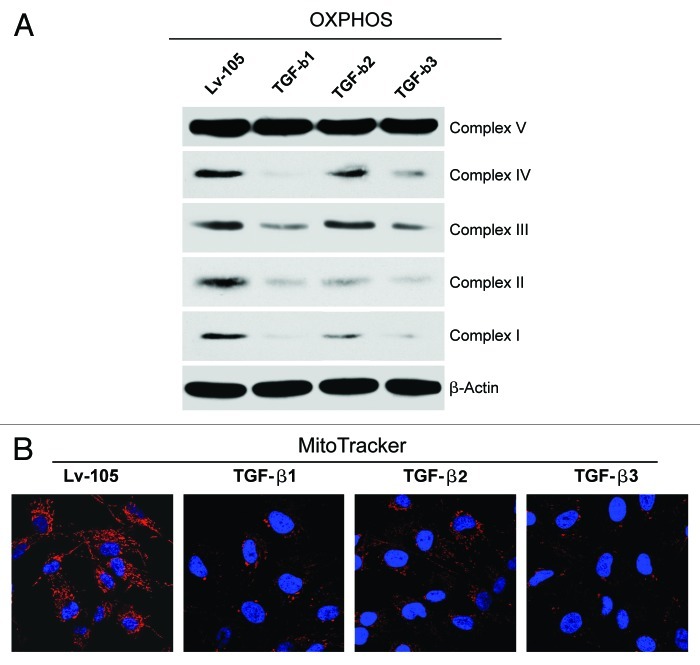

Autophagy is a well-known mechanism for the degradation and turnover of cellular organelles, including mitochondria. Therefore, to evaluate if TGF-β impairs mitochondrial function, TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts were analyzed by immunoblotting with a panel of OXPHOS markers. Figure 4A shows significantly decreased expression levels of key subunits of complexes I, II, III and IV in TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 fibroblasts relative to control cells. Similarly, fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β2 display reductions in the subunits of mitochondrial complexes I, II and IV.

Figure 4. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 show impaired mitochondrial function. (A) Cell lysates from TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 and Lv-105 control fibroblasts were subjected to immunoblot analysis with a panel of antibodies against OXPHOS subunits. Note that all three TGF-β isoforms induce a decrease in the expression of key subunits of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes, relative to control cells (complex IV, COXII; complex III, Core 2 subunit; complex II, 30KDa FeS subunit; complex I, 20KDa subunit). However, TGF-β2 fibroblasts do not show a strong downregulation of complex III. β-actin was used as loading control. (B) Decreased mitochondrial activity of TGF-β-fibroblasts was independently confirmed by MitoTracker staining (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). MitoTracker labels only “healthy” mitochondria, with an active membrane potential. Original magnification, 60×.

To independently validate these data, we next assessed mitochondrial membrane potential, using MitoTracker staining. MitoTracker only labels “healthy” mitochondria with an active membrane potential and, thus, is a measure of mitochondrial activity. Figure 4B shows a strong reduction in mitochondrial activity in fibroblasts overexpressing the three TGF-β ligands.

Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands promote tumor growth independently of angiogenesis

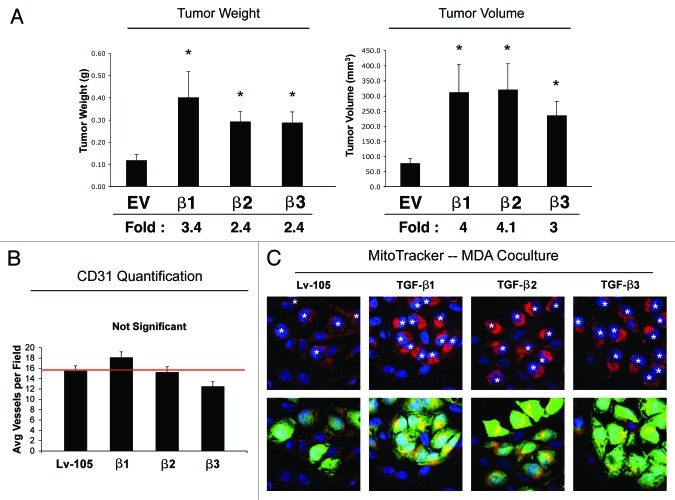

To evaluate if TGF-β expressing fibroblasts play a role in breast tumorigenesis, we employed a mouse xenograft model. Fibroblasts harboring the TGF-β ligands or the vector-alone control (Lv-105) were co-injected with MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells into the flanks of immunodeficient mice. After 4 weeks, the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were harvested and measured. Figure 5A shows that fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands all promote the growth of MDA-MB-231 cells, leading to increased tumor weight (2.4- to 3.4-fold) and volume (3- to 4-fold), compared with empty vector control cells.

Figure 5. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 promote tumor growth, in an angiogenesis-independent manner. (A) Tumor Growth. To evaluate the tumor-promoting properties of TGF-β-fibroblasts, we used a xenograft model. TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 or Lv-105 control fibroblasts were co-injected with MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells into the flanks of athymic nude mice. After 4 weeks tumors were analyzed. Note that all three TGF-β isoforms induce an increase in tumor weight and volume, compared with the Lv-105 empty vector control. Fold increases are as indicated. n = 10. All (*) p-values were < 0.05. (B) Tumor Angiogenesis. To evaluate if fibroblast-derived TGF-β promote tumor growth by increasing tumor angiogenesis, frozen tumor sections were analyzed by CD31 immunostaining. Quantification of the number of CD31 (+) vessels per field indicates that angiogenesis is not modified in the three TGF-β-xenograft groups, relative to control tumors, indicating that TGF-β-fibroblasts stimulate tumor growth independently of angiogenesis. (C) Mitochondrial Activity. TGF-β-fibroblasts enhance mitochondrial activity in adjacent cancer epithelial cells. TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts and control fibroblasts were co-cultured with GFP-positive MDA-MB-231 cells. The cells were then labeled via MitoTracker staining (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Note that fibroblasts expressing TGF-β1, TGF-β2 or TGF-β3 specifically increase the mitochondrial activity of adjacent MDA-MB-231 cells (green), compared with empty vector Lv-105 control. In the top panel, white stars identify the nuclei of GFP-positive MDA-MB-231 cells. Original magnification, 60×.

Since it is known that TGF-β potently promotes angiogenesis, frozen sections from the tumor xenografts were immunostained with an antibody against the endothelial cell marker CD31, and vessel density was quantified. Interestingly, Figure 5B shows that the tumor vessel density was similar in all four experimental groups, suggesting that the tumor-promoting properties of TGF-β fibroblasts are angiogenesis-independent.

Previous data have demonstrated that autophagic and/or glycolytic fibroblasts support the mitochondrial activity and growth of adjacent cancer cells via the paracrine secretion of nutrients and chemical building blocks.44,45 To experimentally evaluate if fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β promote the mitochondrial activity of adjacent cancer cells, we employed a co-culture system consisting of GFP-labeled MDA-MB-231 cells and fibroblasts harboring either the empty vector (Lv-105) or TGF-β ligands. Then, these co-cultures were stained with MitoTracker. Figure 5C shows that MDA-MB-231 cells co-cultured with fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands display a strong increase in mitochondrial activity relative to MDA-MB-231 cells co-cultured with control fibroblasts. These data suggest that TGF-β-overexpressing fibroblasts promote mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in adjacent breast cancer cells via a paracrine mechanism.

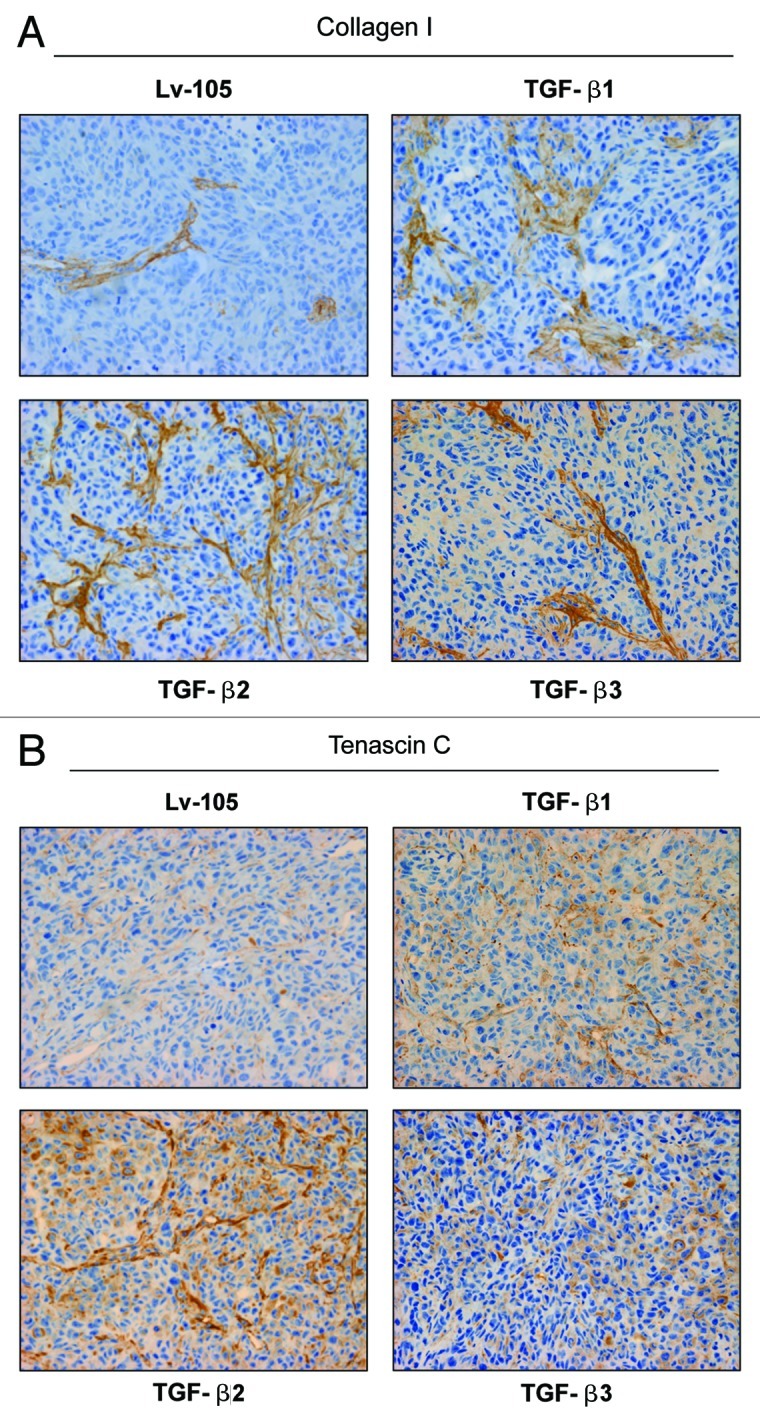

TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts generate tumors with increased deposition of extracellular matrix proteins

During tumor development, CAFs stimulate the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, such as type I collagen and Tenascin C 2. Both components are associated with breast cancer progression and metastasis. It is known that TGF-β is involved in extracellular matrix remodeling. To evaluate if increased extracellular matrix deposition plays a key role in the TGF-β-tumor promoting effects, paraffin-embedded sections from xenograft tumors were immunostained with antibodies directed against type I collagen and Tenascin C. Interestingly, tumors derived from TGF-β ligand expressing fibroblasts display increased deposition of type I collagen (Fig. 6A) and Tenascin C (Fig. 6B), compared with the control tumors. These results suggest that increased extracellular matrix secretion could be one of the mechanism(s) by which TGF-β-overexpressing fibroblasts accelerate tumor growth.

Figure 6. Tumors derived from TGF-β ligand overexpressing fibroblasts display increased extracellular matrix deposition. (A and B) It is well known that TGF-β stimulates the secretion of type I collagen and Tenascin C. To evaluate extracellular matrix deposition, paraffin-embedded xenograft sections were immunostained with antibodies against type I collagen (A) and Tenascin C (B). Note that tumors derived from TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3-fibroblasts show increased levels of type I collagen and Tenascin C relative to the empty vector Lv-105 control. Representative images are shown. Original magnification, 40×.

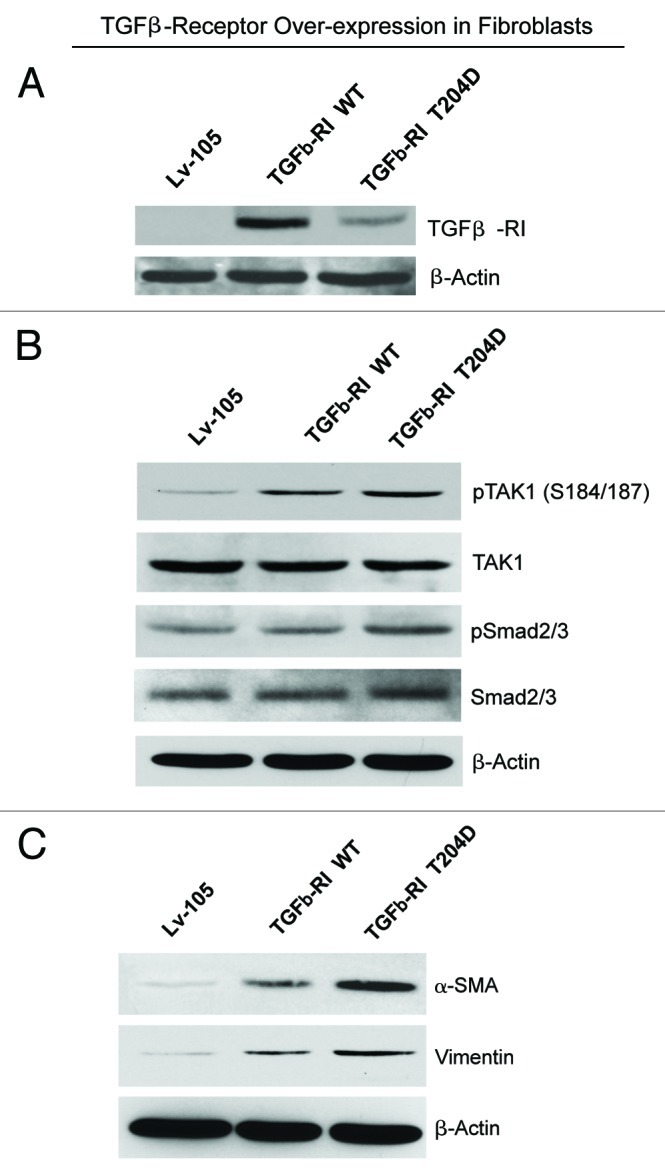

Fibroblasts overexpressing the TGFβ receptor kinase (RI) show myofibroblastic features, with increased activation of the TAK1 pathway

Our current results indicate that fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β ligands promote tumor growth. However, it remains undefined which cell ype within the tumor microenvironment is affected by TGF-β. One possibility is that the tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β-expressing fibroblasts are due to their paracrine effects, leading to the activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells. Alternatively, TGF-β could bind to the TGF-β receptor and activate the TGF-β pathway in the stromal cells, in an autocrine manner.

To distinguish between these two hypotheses, we stably overexpressed TGF-β receptor I (TGFβ-RI) wild-type and a constitutively active mutant (T204D) in hTERT-immortalized human fibroblasts (Fig. 7A). TGF-β exerts its effects by activating downstream canonical (Smad) and non-canonical (TAK1) effectors. To evaluate if TGFβ-RI overexpression leads to the constitutive activation of the TGF-β pathway, fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI were analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies directed against phospho-TAK1 and phospho-Smad2/3. Figure 7B shows that fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI (WT and T204D mutant) display ligand-independent TAK1 activation. Conversely, Smad2/3 was only modestly activated.

Figure 7. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI, WT and a constitutively active mutant (T204D), show increased expression of myofibroblast markers, with activation of the non-canonical TAK1 pathway. (A) TGFβ-RI Expression. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI WT or a constitutively active mutant (T204D) were generated using a lentiviral approach. Their successful overexpression was verified by immunoblotting. (B) TGF-β Signaling. To evaluate the activation of TGF-β signaling, the phosphorylation of TAK1 and Smad2/3 was assessed by immunoblot analysis. Note that phospho-TAK1 is elevated in fibroblasts harboring TGFβ-RI WT and the T204D mutant, relative to the empty vector control. Conversely, phospho-Smad2/3 is only modestly activated. (C) Myofibroblast Markers. The overexpression of TGFβ-RI leads to increased expression of myofibroblast markers. Immunoblot analysis was performed with antibodies direct against α-SMA and vimentin. Note that fibroblasts expressing TGFβ-RI WT or the activated mutant (T204D) show the upregulation of both myofibroblast markers. β-actin was used as a loading control for all experiments.

We next evaluated if fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI show myofibroblast features, indicative of an activated phenotype. Figure 7C shows that the myofibroblast markers α-SMA and vimentin are upregulated in TGFβ-RI expressing fibroblasts. Taken together, these data demonstrate that fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI show constitutive activation of the non-canonical TGF-β signaling cascade, with acquisition of a myofibroblast phenotype.

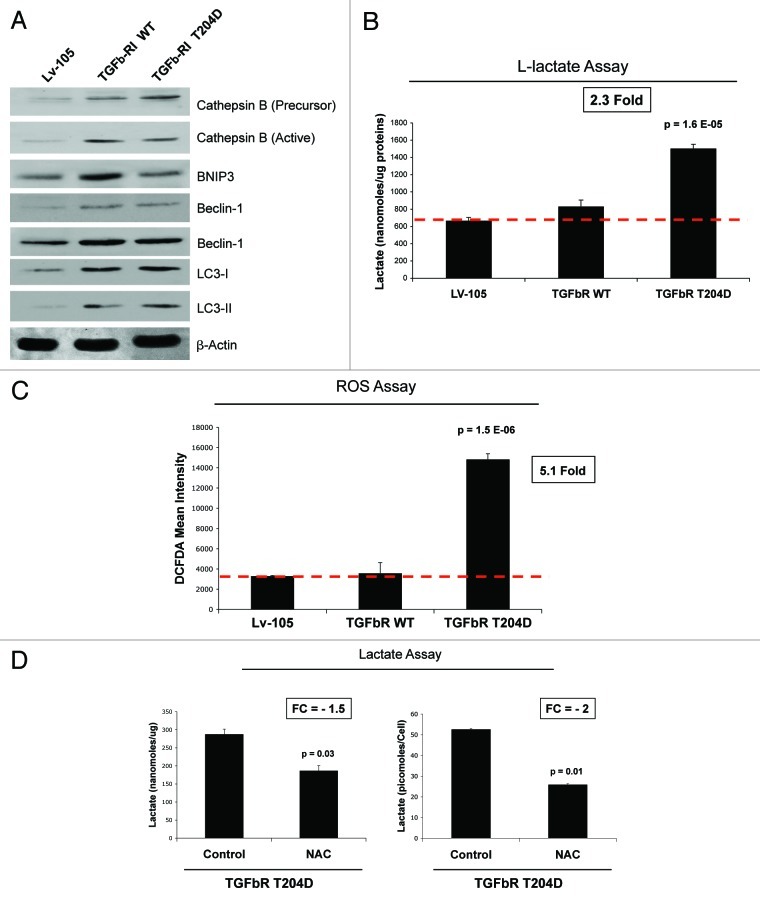

Fibroblasts overexpressing the constitutively active TGFβ receptor kinase (RI; T204D) show increased autophagy and oxidative stress-induced aerobic glycolysis

We next evaluated the metabolic profiles of fibroblasts with the constitutive activation of the TGF-β pathway. First, we investigated if the constitutive expression or activation of TGFβ-RI induces an autophagic program in stromal cells. TGFβ-RI WT and mutant (T204D) fibroblasts were subjected to immunoblot analysis with a panel of autophagy markers. Figure 8A shows that expression of both WT and T204D mutant TGFβ-RI strongly increases the levels of autophagy (cathepsin B, LC3 and Beclin-1) and mitophagy (BNIP3) markers, relative to empty-vector controls. Increased mitophagy/autophagy is often associated with increased glycolysis. Thus, we evaluated the ability of TGFβ-RI-fibroblasts to generate L-lactate. Interestingly, the constitutively active TGFβ-RI mutant fibroblasts showed increased secretion of L-lactate (> 2-fold), relative to control fibroblasts processed in parallel (Fig. 8B). Conversely, TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts did not show any significant increases in L-lactate secretion.

Figure 8. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI WT and the activated mutant (T204D) show increased autophagy, glycolysis and oxidative stress. (A) Autophagy. Cell lysates from Lv-105 control fibroblasts and fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI (WT and T204D mutant) were subjected to immunoblot analysis with several autophagy/mitophagy markers. Note that that expression of TGFβ-RI increases the levels of cathepsin B (precursor and active form), Beclin-1, LC3 (I, precursor I and II, cleaved form) and BNIP3. β-actin was used as equal loading control. (B) Lactate Assay. Cell culture media from Lv-105 control and TGFβ-RI (WT and mutant) fibroblasts were analyzed to determine lactate concentration. Lactate concentrations were normalized for protein content. Note that TGFβ-RI T204D fibroblasts, but not TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts, display a > 2-fold increase of L-lactate generation, compared with empty vector control processed in parallel. P-values are as indicated. (C) Oxidative Stress. ROS production was measured by FACs analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Note the TGFβ-RI (T204D) fibroblasts, but not TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts, display a > 5-fold increase in ROS production, relative to the empty vector control. (D) Antioxidant Treatment. Lactate concentration was measured on the cell culture media of TGFβ-RI T204D mutant fibroblasts treated with vehicle alone or NAC (10 mM) for 24 h. Values were normalized for protein content (left) or cell number (right). Note that NAC treatment induces a dramatic reduction of L-lactate secretion in fibroblasts overexpressing the TGFβ-RI constitutively active T204D mutant. P-values are as indicated. NAC, N-acetyl-cysteine.

It is well known that oxidative stress is a potent inducer of autophagy and glycolysis.46 To evaluate if activation of the TGF-β pathway promotes increased oxidative stress in stromal cells, we examined the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in fibroblasts harboring the empty vector (Lv-105), or TGFβ-RI (WT vs. T204D). Notably, TGFβ-RI mutant (T204D) fibroblasts show a > 5-fold augmentation of ROS production, relative to control cells (Fig. 8C). Conversely, TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts do not show this phenotype.

We next asked if increased L-lactate secretion of TGFβ-RI (T204D) mutant fibroblasts is dependent on increased oxidative stress. To this end, TGFβ-RI (T204D) fibroblasts were treated with a potent antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC, 10 mM), for 24 h. Then, L-lactate accumulation was measured in the conditioned media. Figure 8D shows that NAC treatment decreases L-lactate generation by ~2-fold, indicating that the L-lactate production by constitutively-active TGFβ-RI mutant fibroblasts is strictly dependent on oxidative stress.

Fibroblasts overexpressing the TGFβ receptor kinase (RI) promote tumor growth, independently of angiogenesis

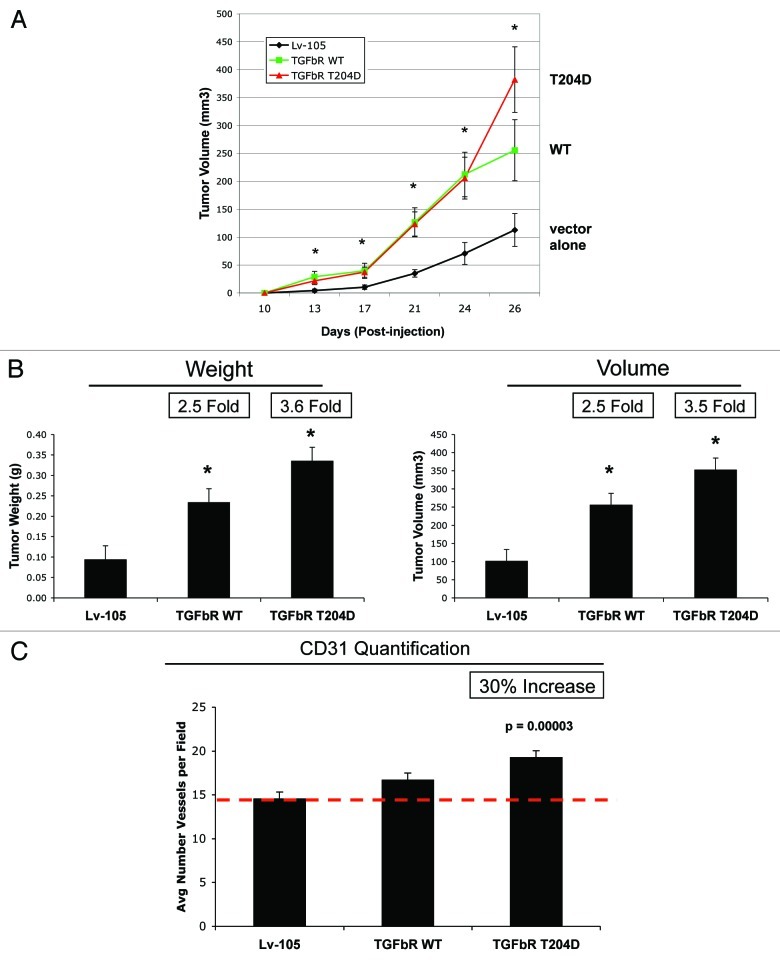

To determine the ability of fibroblasts expressing TGFβ-RI to promote tumor growth, we employed a tumor xenograft assay. Fibroblasts harboring the empty vector (Lv-105) or TGFβ-RI (WT vs. the T204D mutant) were co-injected with MDA-MB-231 cells into the flanks of nude mice. Tumor growth was monitored over a 4-week period, after which the mice were sacrificed, and tumors were harvested and measured. Figure 9A shows that fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβRI greatly increase tumor growth rates, relative to control cells. Figure 9B shows the measurements of tumor weight and volume, demonstrating that fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI WT promote a 2.5-fold increase in tumor growth, while fibroblasts harboring the TGFβ-RI mutant (T204D) induce a 3.5-fold increase, compared with control cells.

Figure 9. Fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI promote tumor growth, without a dramatic increase in angiogenesis. (A and B) Tumor Growth. To evaluate the tumor-promoting properties of TGFβ-RI (WT and mutant) fibroblasts, we used a xenograft model. Fibroblasts (control, TGFβ-RI WT and TGFβ-RI mutant) were co-injected with MDA-MB-231 cells into the flanks of athymic nude mice. (A) Tumor growth rates were monitored over a 4-week period. P-values were < 0.02 (B) After 4-weeks, tumors were dissected to determine weight and volume. Note that fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI WT or T204D mutant induce an increase of tumor weight and volume, compared with the empty vector Lv-105 controls. Fold increases are as indicated. n = 10. P-value were < 0.008. (C) Tumor Angiogenesis. Tumor frozen sections were immunostained with anti-CD31 antibodies. Quantification of CD31-positive vessels indicate that only fibroblasts overexpressing TGFβ-RI mutant induces a 30% increase in tumor angiogenesis, compared with the empty vector control or TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts. However, the increase in angiogenesis is modest, relative to the increase in tumor growth.

To investigate if increased angiogenesis is one of the mechanism(s) of the tumor-promoting effects of TGFβ-RI fibroblasts, CD31 immunostaining and quantitation were performed on tumor xenografts. Figure 9C shows that the tumors derived from TGFβ-RI WT fibroblasts display a vessel density similar to the control tumors. However, tumors derived from fibroblasts with constitutively active TGFβ-RI show a 30% increase in vessel density, as compared with the control. However, as the fibroblasts with constitutively active TGFβ-RI show a 3.5-fold increase in tumor growth, it is unlikely that a 30% increase in angiogenesis is the mechanism driving increased tumorigenesis.

These data indicate that activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells drives tumorigenesis via an autocrine-loop in fibroblasts. Mechanistically, activation of the TGF-β pathway induces the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells, with increased oxidative stress, autophagy and glycolysis, thereby promoting oxidative mitochondrial metabolism and anabolic growth of adjacent cancer cells via energy-transfer.

Dissecting the compartment-specific action of TGF-β in breast tumorigenesis: TGF-β ligand overexpression in cancer cells drives tumor growth, but TGFβ receptor kinase (RI) overexpression in cancer cells does not affect tumor growth

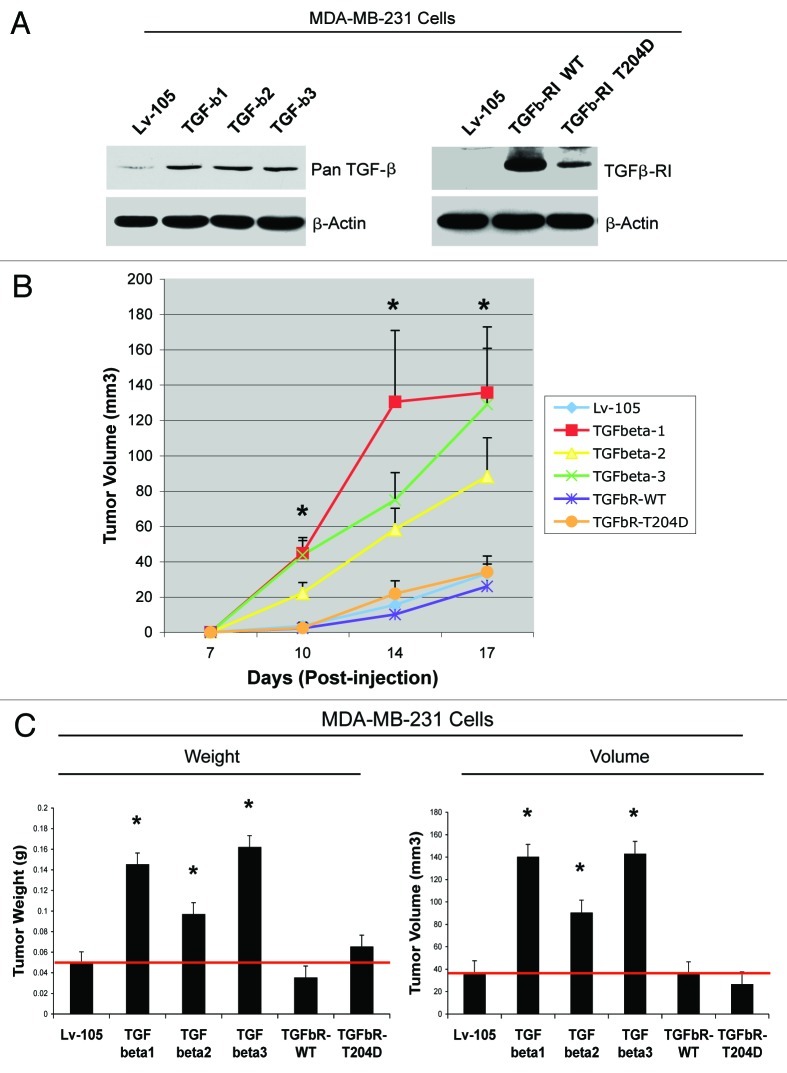

We next evaluated if activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells drives tumor growth. One hypothesis is that fibroblast-derived TGF-β ligands could also act on cancer cells in a paracrine fashion. To this end, we overexpressed TGF-β ligands in MDA-MB-231 cells. In parallel, we also overexpressed TGFβ-RI (WT or the constitutively active T204D mutant) in MDA-MB-231 cells. Empty vector (Lv-105) control cells were generated in parallel. In this way, we reasoned that we could distinguish between the cell-autonomous effects of the activation of the TGF-β pathway (cancer cells overexpressing the activated TGF-β receptor), vs. the paracrine role of cancer cell-derived TGF-β on the tumor microenvironment (cancer cells overexpressing TGF-β ligands). Figure 10A shows that all three TGF-β ligands and TGF-β-RI were successfully overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.

Figure 10. MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells overexpressing TGF-β ligands, but not TGFβ-RI, promote tumor growth. (A) TGF-β-ligands (1, 2 and 3) or TGFβ-receptors [RI; WT vs. the activated mutant (T204D)] were overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 cells. Lv-105 empty vector control cells were generated in parallel. Overexpression was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibodies directed against pan-TGF-β or the TGFβ-RI. β-actin was used as an equal loading control. (B and C) MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either Lv-105 (empty vector), TGF-β-ligands (1, 2 and 3) or TGFβ-receptors [RI; WT vs. the activated mutant (T204D)] were injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice. (B) Tumor growth rates. P-values were < 0.02. (C) Tumor weight and volume was measured 3 weeks post-injection. Note that MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing TGF-β-ligands (1, 2 and 3) promote tumor growth, resulting in a 3-, 2- and 3.4-fold increase in tumor weight, respectively, and a 3.9-, 2.5- and 3.9-fold increase in tumor volume, respectively, relative to control cells. Conversely, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing TGFβ-receptors [RI; WT vs. the activated mutant (T204D)] do not show any changes in tumor growth, compared with the vector-alone controls. P-values were < 0.05. n = 10 tumors per experimental group.

To investigate the effects of TGF-β ligands and TGFβ-RI overexpression in breast cancer cells in vivo, transfected MDA-MB-231 cells were injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice. Interestingly, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing TGFβ-RI (WT or the T204D mutant) show tumor growth rates similar to the empty vector control (Lv-105). Conversely, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing TGF-β ligands display a dramatic increase in tumor growth, relative to the empty vector control (Fig. 10B and C). These data suggest that activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not support tumor growth, but rather cancer cell-derived TGF-β ligands act in a paracrine fashion on the tumor microenvironment by activating TGF-β signaling in stromal cells.

Cancer cell-derived TGF-β ligands induces the metabolic reprogramming of fibroblasts, with increased autophagy, glycolysis and Cav-1 downregulation

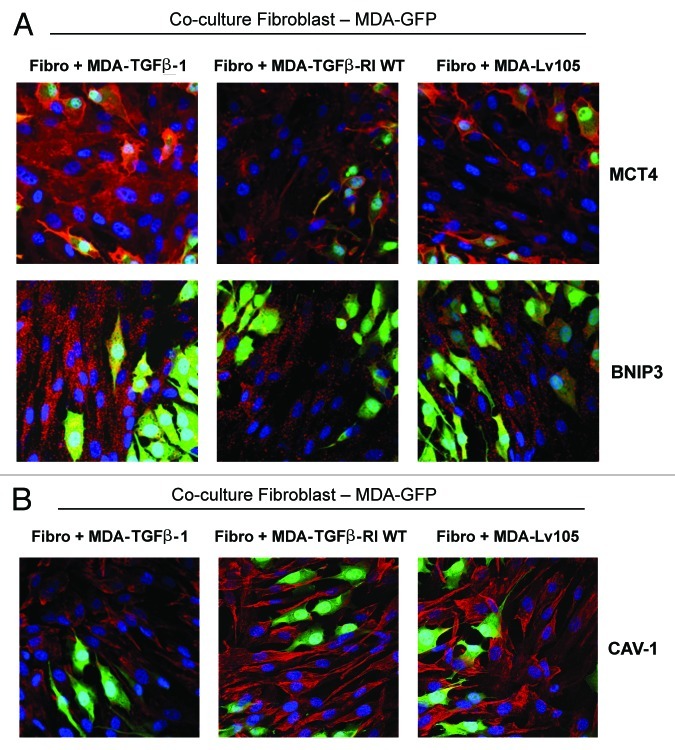

To directly validate the hypothesis that cancer cell-derived TGF-β ligands activate TGF-β signaling in adjacent fibroblasts, leading to their metabolic reprogramming, we employed a co-culture system. hTERT-immortalized normal fibroblasts were co-cultured with GFP-positive MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing TGF-β1, TGFβ-RI WT or the empty vector control (Lv-105) for 4 d. Then, cells were immunostained with antibodies directed against MCT4 (a marker of glycolysis and oxidative stress), BNIP3 (a marker of autophagy/mitophagy) and Cav-1 (a marker whose loss reflects oxidative stress and a lethal microenvironment).

Figure 11A shows that the expression levels of MCT4 and BNIP3 are increased in fibroblasts co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells secreting the TGF-β ligand. However, these paracrine effects were not observed with MDA-MB-231 cells harboring the TGF-β receptor (RI) or the empty-vector control (Lv-105). Similarly, Cav-1 expression levels are decreased in fibroblasts co-cultured with MDA-MB-231 cells secreting the TGF-β ligand. Again, such paracrine effects were not observed with MDA-MB-231 cells harboring the TGF-β receptor (RI) or the empty-vector control (Fig. 11B). These results demonstrate that cancer cell-derived TGF-β ligands affect neighboring stromal cells, inducing Cav-1 downregulation and the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells toward a catabolic phenotype.

Figure 11. Cancer cell-derived TGF-β1 induces the metabolic reprogramming of fibroblasts, with increased autophagy, glycolysis and Cav-1 downregulation. (A and B) To directly evaluate if cancer cell-derived TGF-β ligands activates TGF-β signaling in adjacent fibroblasts, we employed a co-culture system. Normal fibroblasts were co-cultured with GFP-positive MDA-MB-231 cells (green) overexpressing TGF-β1 for 4 d. Then, the cells were immunostained with antibodies directed against MCT4, BNIP3, or Cav-1 (red). Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (blue). As controls, fibroblasts co-cultured with empty vector Lv-105-MDA-MB-231 cells or TGFβ-RI WT-MDA-MB-231 cells were fixed and stained in parallel. Representative images from confocal cross-sections are shown. (A) The expression of BNIP3 (a mitophagy marker) and MCT4 (a marker of glycolysis and oxidative stress) is increased in fibroblasts co-cultured with TGF-β1-MDA-MB-231 cells, as compared with fibroblasts co-cultured with Lv-105-MDA-MB-231 and TGFβ-RI WT-MDA-MB-231. (B) Cav-1 expression is decreased in fibroblasts co-cultured with TGF-β1-MDA-MB-231 cells, as compared with fibroblasts co-cultured with Lv-105-MDA-MB-231 and TGFβ-RI WT-MDA-MB-231. These results demonstrate that cancer cell-derived-TGF-β1 affects stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, inducing Cav-1 downregulation and the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells toward a catabolic phenotype. Original magnification, 40×.

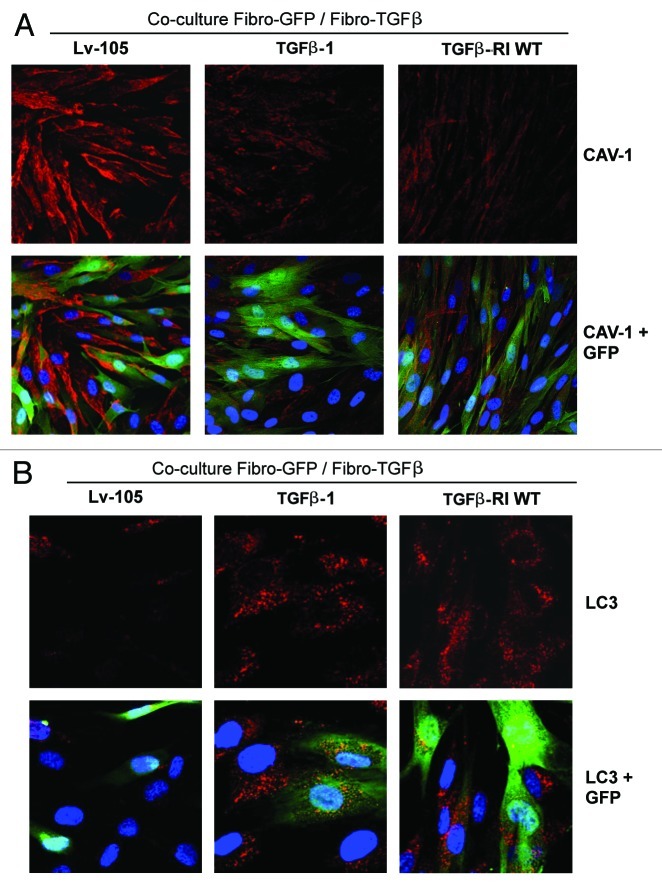

We next asked if TGF-β-activated fibroblasts can also affect neighboring normal stromal cells by inducing Cav-1 downregulation. To this end, GFP-positive normal fibroblasts were co-cultured with fibroblasts harboring the TGF-β ligand, the TGF-β receptor (RI) or the empty-vector alone (Lv-105). Then, these cells were immunostained with antibodies directed against Cav-1 or LC3. Importantly, Cav-1 expression is lost during autophagy, while increased LC3 punctate staining marks the presence of autophagosomes.

Figure 12A shows that Cav-1 levels are decreased in normal fibroblasts co-cultured with activated fibroblasts harboring either the TGF-β ligand or the TGF-β receptor (RI), but not the empty-vector alone (Lv-105). Similarly, punctate LC3 staining is greatly augmented only in normal fibroblasts co-cultured with TGF-β activated fibroblasts (Fig. 12B). These results indicate that TGF-β-activated fibroblasts can induce a bystander effect, effectively spreading the loss of Cav-1 and activating an autophagic process in “normal” neighboring fibroblasts.

Figure 12. TGF-β activated fibroblasts induce the metabolic reprogramming of “normal” fibroblasts, with increased autophagy and Cav-1 downregulation. (A and B) To evaluate if fibroblasts with an activated TGF-β pathway affect adjacent stromal cells, GFP-positive normal fibroblasts (green) were co-cultured with fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1, TGFβ-RI WT or the Lv-105 empty vector control for 3 d. Then, cells were immunostained with antibodies against Cav-1 or LC3 (red). To detect LC3, prior to fixation, cells were incubated with HBSS in the presence of 25 μM Chloroquine for 6 h. Fibroblasts co-cultured with fibroblasts overexpressing TGF-β1 or TGFβ-RI WT display decreased levels of Cav-1 (A), but increased activation of LC3 (B), as compared with fibroblasts co-cultured with control fibroblasts. Importantly, matched images were acquired using identical exposure settings. Original magnification, 40× for (A), and 80× for (B).

In summary, our data indicate that the role of TGF-β in tumorigenesis is compartment-specific. Ligand-dependent or cell-autonomous activation of TGF-β signaling in stromal cells induces their metabolic reprogramming, with increased oxidative stress, autophagy/mitophagy and glycolysis via the downregulation of Cav-1. These metabolic alterations can then spread to neighboring fibroblasts and profoundly accelerate the growth of breast cancer cells. Conversely, activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not directly influence tumor growth, but cancer cell-derived-TGF-β ligands can metabolically reprogram adjacent stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, leading to enhanced tumor growth. Thus, TGF-β activation in cancer-associated fibroblasts spreads like a virus, converting normal fibroblasts to an autophagic phenotype. As such, stromal TGF-β activation functionally acts as the “Pied Piper of Hamelin,” actively driving adjacent normal fibroblasts toward a catabolic state that fuels tumor growth via an insidious energy-transfer mechanism.

Discussion

The TGF-β-mediated autocrine loop and cancer metabolism

A loss of stromal Cav-1 is a biomarker of poor prognosis in human breast cancers.19,20 Mechanistically, a loss of Cav-1 in CAFs induces the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells and is associated with increased autophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction and aerobic glycolysis.28,38 As a consequence, Cav-1-low CAFs generate nutrients (such as L-lactate, ketone bodies, glutamine, and other chemical building blocks) that can “fuel” mitochondrial metabolism and the anabolic growth of adjacent epithelial cancer cells.

It is also known that Cav-1 negatively regulates TGF-β signaling, and that loss of Cav-1 is associated with hyperactive TGF-β signaling and with a fibroblast-to-myofibroblast conversion.23,25 It remains unknown, however, if hyperactivation of the TGF-β pathway contributes to the metabolic reprogramming of Cav-1-low CAFs. It also remains unresolved what is the compartment-specific role TGF-β signaling in cancer cells and in stromal cells.

To address these issues, here, we have overexpressed (1) TGF-β ligands or (2) the TGFβ receptor kinase (RI), in stromal cells and in breast cancer cells. We show that the role of TGF-β in tumorigenesis is highly compartment-specific. Our results indicate that TGF-β promotes tumorigenesis by altering the metabolism of cancer-associated fibroblasts and shifting them toward catabolic metabolism. Importantly, the tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β are independent of the cell type generating TGF-β.

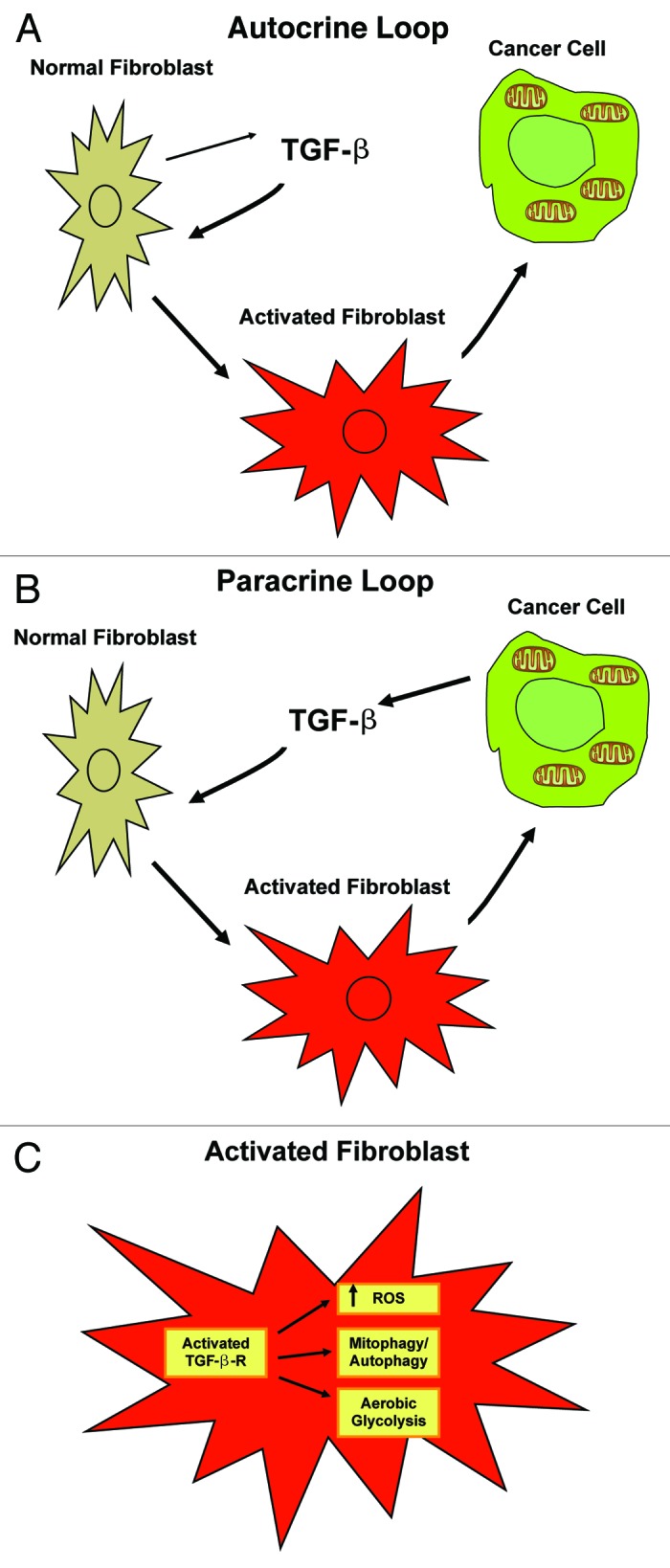

Ligand-dependent or cell-autonomous activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells induces their metabolic reprogramming, with increased oxidative stress, autophagy/mitophagy and aerobic glycolysis, with the downregulation of Cav-1. These metabolic alterations can spread among neighboring fibroblasts and greatly sustain the anabolic growth of breast cancer cells. Thus, stromal-derived TGF-β activates TGF-β signaling in stromal cells in an autocrine fashion (Fig. 12A), leading to fibroblast activation, as judged by increased expression of myofibroblast markers, and metabolic reprogramming, with a shift toward catabolic metabolism and oxidative stress (Fig. 12C). Conversely, activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not influence tumor growth, but cancer cell-derived-TGF-β ligands affect stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, leading to fibroblast activation and enhanced tumor growth (Fig. 12B).

Previous studies have demonstrated that autocrine TGF-β signaling generates a tumor-promoting microenvironment by initiating and sustaining the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts.47 In this previous study, however, the contributions of metabolic alterations in the tumor microenvironment were not evaluated.

The role of TGF-β in the regulation of cancer metabolism remains largely unexplored. TGF-β was shown to induce autophagy in supporting cells of the glomerular capillaries, as an escape mechanism against apoptosis, through activation of the TAK and Akt pathways.48 In addition, TGF-β can enhance the glycolytic power of renal cells, as judged by decreased oxygen consumption, inhibition of the ATPase activity and increased L-lactate production.49 Our results clearly show that ligand-dependent or constitutive activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells potently induces an autophagic program specifically in the stromal cells of the tumor microenvironment, and promotes glycolysis and oxidative stress. We also show that TGF-β-activated fibroblasts promote the mitochondrial activity of adjacent cancer cells. Thus, our data establish a clear causative connection between the tumor-promoting effects of TGF-β signaling and the metabolic reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment.

Compartment-specific role of TGF-β signaling in the breast cancer tumor microenvironment: Stromal vs. epithelial TGF-β activation

It is well known that TGF-β has potent tumor inhibitory properties and also potent transforming functions.8 One of the theories to explain this paradox is that TGF-β functions as a tumor suppressor in normal cells during tumor initiation, but as a tumor promoter during cancer progression and metastasis. Our data provide an alternative explanation to explain the dual role of TGF-β during tumorigenesis.

We show here that the role of TGF-β in tumorigenesis is compartment-specific, and TGF-β signaling in stromal cells induces their metabolic reprogramming, and this event is required for its tumor-promoting effects. It is also known that many of the TGF-β tumor-suppressor functions occur through the canonical Smad-signaling cascade.13 Consistent with this idea, in our system, TGF-β-activated fibroblasts showed little, if any, Smad-activation, indicating the tumor-inhibitory arm of the TGF-β pathway may be suppressed. Notably, we observed that the pro-tumorigenic properties of TGF-β-activated fibroblasts were independent from its other functions, such as angiogenesis, that are traditionally believed to act downstream of the TGF-β pathway. Our data indicate that activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells induces their metabolic reprogramming, with increased oxidative stress, autophagy/mitophagy and aerobic glycolysis and the downregulation of Cav-1.

Conversely, activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not influence tumor growth, but cancer cell-derived-TGF-β ligands affect stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, leading to enhanced tumor growth. Using a coculture system of breast cancer cells and fibroblasts, we observed that cancer cell-derived TGF-β activates TGF-β signaling in adjacent fibroblasts, inducing the upregulation of MCT4 (a marker of glycolysis and oxidative stress) and BNIP3 (a marker of autophagy/mitophagy) and the loss of Cav-1 (a marker of oxidative stress and a lethal microenvironment). Thus, we believe that by inducing the metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells toward a more catabolic phenotype, cancer cell-derived TGF-β promotes tumor growth.

In conclusion, our data provide novel insights into the role of TGF-β pathway in breast tumorigenesis, and disclose a previously unrecognized role for TGF-β signaling in generating a tumor-promoting microenvironment by shifting stromal cells toward catabolic metabolism. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13. Autocrine and paracrine TGF-β signaling in cancer-associated fibroblasts fuels the anabolic growth of adjacent breast cancer cells. (A) Autocrine Loop. Stromal-derived TGF-β activates signaling in stromal cells in an autocrine fashion, leading to fibroblast activation. Activated catabolic fibroblasts then promote the mitochondrial activity and anabolic growth of adjacent epithelial cancer cells. (B) Paracrine Loop. Cancer cell-derived-TGF-β ligands affect stromal cells in a paracrine fashion, leading to fibroblast activation (catabolism) and enhanced tumor growth. However, activation of the TGF-β pathway in cancer cells does not influence tumor growth. (C) Fibroblast Activation. Ligand-dependent or cell-autonomous activation of the TGF-β pathway in stromal cells induces fibroblast activation. Features of activated fibroblasts include increased expression of myofibroblast markers, and metabolic reprogramming toward catabolic metabolism. Thus, TGF-β-activated fibroblasts show increased oxidative stress, autophagy/mitophagy and glycolysis, and downregulation of Cav-1. These metabolic alterations can also spread to neighboring “normal” fibroblasts in a paracrine fashion and greatly sustain the anabolic growth of breast cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) stably transfected with GFP (a generous gift from Dr. A. Fatatis, Drexel University) and human immortalized fibroblasts (hTERT-BJ1), were both cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral vectors (all from GeneCopoeia, Inc.) encoding TGF-β1 (EX-A1003-Lv-105), TGF-β2 (EX-Z0977-Lv-105), TGF-β3 (EX-Q0079-Lv-105), TGFβ-RI WT (EX-A0923-Lv-105), TGFβ-RI T204D (CS-A0923-Lv-105) or the empty vector (EX-NEG-Lv-105), were stably transfected into the 293Ta packaging cells (GeneCopoeia, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Two days post-transfection, the viral supernatant was collected, centrifuged, filtered [(0.45 µM PES (polyethersulfone) low-protein-binding filter] and added to the target cells (either hTERT-BJ1 fibroblasts or MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells) in the presence of 5 µg/ml polybrene. Twenty-four hours post-infection, media-containing virus was removed and replaced with standard media. Cells were selected with 1.5 µg/ml (for hTERT-BJ1) or 2.0 µg/ml (for MDA-MB-231) puromycin.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 60 mM octyl-glucoside), supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). After rotation at 4°C for 40 min, samples were centrifuged 10 min at 13,000× g at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected to remove insoluble debris. Protein concentrations were analyzed using the BCA reagent (Pierce-Thermo Scientific). For HIF-1α detection, cells were scraped in urea lysis buffer (10 mM TRIS-HCl pH 6.6, 6.7 M urea, 10% glycerol, 1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, with protease inhibitors), homogenized and incubated on ice for 10 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged 10 min at 13,000 × g at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (BioRad). An equal amount of proteins (30 µg) was boiled for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE (10 or 12% acrylamide) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with TBS/Tween-20 (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20) supplemented with 1% BSA and 4% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature. For phospho-antibody, the blocking solution contained only 5% BSA in TBS-Tween-20 (without non-fat dry milk). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed and incubated for 30 min with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies [anti-mouse 1:6,000 dilution (Pierce) or anti-rabbit 1:5,000 (BD Biosciences/PharMingen)] at room temperature, and revealed with Supersignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce). As internal control, all membranes were subsequently stripped (Restore Western Blot Stripping Solution, Thermo Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature and re-probed with anti β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich A5441).

The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting: smooth muscle actin (Santa Cruz; sc-53142); beclin-1 (Novus Biologicals; NBP1–00085); BNIP3 (Abcam; ab10433); cathepsin B (FL-339) (Santa Cruz; sc-13985); LC3 (Abcam; ab48395); HIF-1α (BD Biosciences; 610959); Cav-1 (mAb clone 2297) (BD Biosciences; 610407); Vimentin (R28) (Cell Signaling; 3932); Calponin 1/2/3 (FL-297) (Santa Cruz; sc-28545); phospho-AKT (Thr-308) (Cell Signaling; 4056); phospho-AKT (Ser-473) (Cell Signaling; 9271); total AKT (Cell Signaling; 9272); APG5 (Biosensis; R-111–100); phospho-Smad2/3 (Ser-423/425) (Santa Cruz; sc-11769); total Smad2/3 (Cell Signaling; 5678); phospho-Tak1 (Thr-184/187) (Cell Signaling; 4531); total Tak1 (Cell Signaling; 4505); pan-TGF-β (Cell Signaling; 3711); TGF-β-RI (V22) (Santa Cruz; sc-398); OXPHOS cocktail (Mitosciences; MS601).

Mitochondrial activity

Fibroblasts were seeded on glass coverslips alone or in co-culture with GFP-MDA-MB-231 cells in 12-well plates in complete media. After 24 h, the media was changed to DMEM containing 2% FBS. After 72 h, cells were incubated with the pre-warmed MitoTracker staining solution (25 nM, MitoTracker Orange; CMTMRos, cat#M7510, Invitrogen). Then, the cells were washed in PBS supplemented with calcium and magnesium three times and fixed with 2% PFA. Cells were incubated with DAPI nuclear stain (D3571, Invitrogen) and mounted with Prolong Gold Anti-Fade mounting reagent (P36930, Invitrogen). Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM510 meta-confocal system with a 60× objective.

L-lactate assay

100,000 cells were plated onto 12-well plates in standard media. After 24 h, the media was changed to DMEM containing 2% FBS. After 2 days, the media was collected to measure lactate concentration using the EnzyChromTM L-Lactate Assay Kit (cat #ECLC-100, BioAssay Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were normalized to the cellular protein content or for the number of cells. For NAC treatment, cells were incubated with 10 mM NAC (N-acetyl-cysteine) for 24 h before L-lactate measurement.

ROS assay

Cells were plated at a density of 130,000 per well in 12-well plates in complete media. After 48 h, cells were washed and incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 10 μM CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen). Then, cells were washed 3× with HBSS, and placed in standard media for 15 min at 37°C. Then, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, resuspended in PBS, and ROS were quantified by FACS using BD LSRII (BD Bioscience). Results were analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

Animal studies

All animals were housed and maintained in a barrier facility at the Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University under National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Mice were kept on a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to chow and water. Approval for all animal protocols was obtained via the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (1 × 106 cells) alone or admixed with fibroblasts (3 × 105 cells) were resuspended in 100 µl of sterile PBS and injected into the flanks of athymic nude mice (NCRNU, Taconic Farms; 6–8 weeks of age). Tumor growth was monitored for 4 weeks post-injection; the mice were sacrificed and tumors were dissected to determine weight and size using calipers. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula (X2Y)/2, where X and Y are the short and long tumor dimensions, respectively. Tumors were either fixed with 10% formalin or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane.

Quantification of tumor angiogenesis

CD31 immunostaining was performed on frozen tumor sections (6 µm). A three-step biotin-streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase method was used for antibody detection. Frozen tissue sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 4°C and washed with PBS. After fixation, sections were blocked with 10% rabbit serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (BS Biosciences). Then, the sections were incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG (1:200) antibody and streptavidin-HRP. Immunoreactivity was revealed with 3.3′-diaminobenzidine. The total number of vessel per unit area was scored, and the data was represented graphically.

Immuno-histochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor sections were de-paraffinized, rehydrated and washed in PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0 for 10 min using a pressure cooker. After blocking with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, sections were incubated with 10% goat serum for 1 h. Then, sections were incubated with primary antibodies [Tenascin C (Leica Microsystems; NCL-TENAS-C) and type I collagen (Cell Sciences; PS065)] overnight at 4°C. Antibody binding was detected using a biotinylated secondary (Vector Labs) followed by streptavidin-HRP (Dako). Immunoreactivity was revealed using 3.3′-diaminobenzidine. Then, sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin.

Immuno-fluorescence

For fibroblast/cancer cell co-culture experiments, fibroblasts and GFP-positive MDA-MB-231 cells [harboring TGF-β1, TGFβ-RI WT or the vector alone control (Lv-105)] were plated onto glass coverslips at the ratio 5:1 in 12-well plates in standard media. The day after, the media was changed to DMEM with 10% NuSerum (BD Biosciences) and cells were maintained in coculture for 96 h. For fibroblast-fibroblast co-cultures, GFP-positive hTERT-fibroblasts and transfected fibroblasts [harboring TGF-β1, TGFβ-RI WT or the vector alone control (Lv-105)] were plated onto glass coverslips at the ratio 2:3 in 12-well plates in standard media. The day after, the media was changed to DMEM with 10% NuSerum (BD Biosciences) and cells were maintained in coculture for 72 h. Cells were fixed with 2% PFA and permeabilized with cold methanol. To detect LC3, cells were maintained in coculture for 66 h, and then were incubated for 6 h with HBSS/40 mM Hepes and 25 µM chloroquine. Cells were fixed with 2% PFA and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 plus 0.2% BSA. Then, to quench free aldehyde groups, cells were incubated with 25 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 10 min. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with anti-Cav-1 (N20) (Santa Cruz; sc-894), anti-BNIP3 (Abcam; ab10433), anti-LC3A/B (Cell Signaling; 4108), or anti-MCT4 (gift of Dr. Nancy Philp) antibodies. Then, the cells were washed, and incubated for 30 min with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. Finally, slides were washed, incubated with the nuclear stain DAPI and mounted.

Acknowledgments

F.S. and her laboratory were supported by grants from the Breast Cancer Alliance (BCA) and the American Cancer Society (ACS). U.E.M. was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Margaret Q. Landenberger Research Foundation. M.P.L. was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (R01-CA-080250; R01-CA-098779; R01-CA-120876; R01-AR-055660), and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. R.G.P. was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (R01-CA-70896, R01-CA-75503, R01-CA-86072 and R01-CA-107382) and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust. The Kimmel Cancer Center was supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Core grant P30-CA-56036 (to R.G.P.). Funds were also contributed by the Margaret Q. Landenberger Research Foundation (to M.P.L.). This project is funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health (to M.P.L. and F.S.). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. This work was also supported, in part by a Centre grant in Manchester from Breakthrough Breast Cancer in the UK (to A.H.) and an Advanced ERC Grant from the European Research Council.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CAFs

cancer-associated fibroblasts

- Cav-1

caveolin-1

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SMA

smooth muscle actin-alpha

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- TGFβ-RI

TGF-β receptor type I

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21384

References

- 1.Rønnov-Jessen L, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Cellular changes involved in conversion of normal to malignant breast: importance of the stromal reaction. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:69–125. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shekhar MP, Pauley R, Heppner G. Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: extracellular matrix-stromal cell contribution to neoplastic phenotype of epithelial cells in the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:130–5. doi: 10.1186/bcr580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rønnov-Jessen L, Petersen OW. Induction of alpha-smooth muscle actin by transforming growth factor-beta 1 in quiescent human breast gland fibroblasts. Implications for myofibroblast generation in breast neoplasia. Lab Invest. 1993;68:696–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desmoulière A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Löhr M, Schmidt C, Ringel J, Kluth M, Müller P, Nizze H, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces desmoplasia in an experimental model of human pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00432-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padua D, Massagué J. Roles of TGFbeta in metastasis. Cell Res. 2009;19:89–102. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bierie B, Moses HL. Gain or loss of TGFbeta signaling in mammary carcinoma cells can promote metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3319–27. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datto MB, Li Y, Panus JF, Howe DJ, Xiong Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5545–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannon GJ, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–61. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valderrama-Carvajal H, Cocolakis E, Lacerte A, Lee EH, Krystal G, Ali S, et al. Activin/TGF-beta induce apoptosis through Smad-dependent expression of the lipid phosphatase SHIP. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:963–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang CW, Chen CH, Chen CC, Chen JY, Su YH, Chen RH. TGF-beta induces apoptosis through Smad-mediated expression of DAP-kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:51–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy L, Hill CS. Alterations in components of the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathways in human cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:41–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arteaga CL, Hurd SD, Winnier AR, Johnson MD, Fendly BM, Forbes JT. Anti-transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta antibodies inhibit breast cancer cell tumorigenicity and increase mouse spleen natural killer cell activity. Implications for a possible role of tumor cell/host TGF-beta interactions in human breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2569–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI116871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickson MC, Martin JS, Cousins FM, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Akhurst RJ. Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Elsner T, Botella LM, Velasco B, Corbí A, Attisano L, Bernabéu C. Synergistic cooperation between hypoxia and transforming growth factor-beta pathways on human vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38527–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Sotgia F, Mercier I, Pestell RG, Sabel M, et al. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2023–34. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan EK, Ciocca DR, Pouliot N, Natoli A, Restall C, Henderson MA, et al. Stromal cell expression of caveolin-1 predicts outcome in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2035–43. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercier I, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Rosenberg AL, Quong J, Minkeu A, et al. Human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) show caveolin-1 downregulation and RB tumor suppressor functional inactivation: Implications for the response to hormonal therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1212–25. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.8.6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, et al. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3984–4001. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Daumer KM, Milliman JN, Chiavarina B, et al. Tumor cells induce the cancer associated fibroblast phenotype via caveolin-1 degradation: implications for breast cancer and DCIS therapy with autophagy inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2423–33. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sotgia F, Del Galdo F, Casimiro MC, Bonuccelli G, Mercier I, Whitaker-Menezes D, et al. Caveolin-1-/- null mammary stromal fibroblasts share characteristics with human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:746–61. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razani B, Zhang XL, Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Böttinger EP, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 regulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta/SMAD signaling through an interaction with the TGF-beta type I receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6727–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Del Galdo F, Lisanti MP, Jimenez SA. Caveolin-1, transforming growth factor-beta receptor internalization, and the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:713–9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283103d27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Igarashi J, Shoji K, Hashimoto T, Moriue T, Yoneda K, Takamura T, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 downregulates caveolin-1 expression and enhances sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling in cultured vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1263–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00109.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotgia F, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Howell A, Pestell RG, Pavlides S, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 and cancer metabolism in the tumor microenvironment: markers, models, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:423–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-120856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Power surge: supporting cells “fuel” cancer cell mitochondria. Cell Metab. 2012;15:4–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Migneco G, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Flomenberg N, et al. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer: Role of oxidative stress and ketone production in fueling tumor cell metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3485–505. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Trimmer C, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Zhou J, et al. Autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts promotes tumor cell survival: Role of hypoxia, HIF1 induction and NFκB activation in the tumor stromal microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3515–33. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moses H, Barcellos-Hoff MH. TGF-beta biology in mammary development and breast cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a003277. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stover DG, Bierie B, Moses HL. A delicate balance: TGF-beta and the tumor microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:851–61. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bierie B, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) and inflammation in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massagué J. TGF-β signaling in development and disease. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1833. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massagué J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM, Rivadeneira DB, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Wang C, et al. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3256–76. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sotgia F, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Howell A, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP. Understanding the Warburg effect and the prognostic value of stromal caveolin-1 as a marker of a lethal tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:213. doi: 10.1186/bcr2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casey TM, Eneman J, Crocker A, White J, Tessitore J, Stanley M, et al. Cancer associated fibroblasts stimulated by transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-beta 1) increase invasion rate of tumor cells: a population study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlides S, Vera I, Gandara R, Sneddon S, Pestell RG, Mercier I, et al. Warburg meets autophagy: cancer-associated fibroblasts accelerate tumor growth and metastasis via oxidative stress, mitophagy, and aerobic glycolysis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1264–84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Bosch-Marce M, Shimoda LA, Tan YS, Baek JH, Wesley JB, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10892–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Cell biology. The TASCC of secretion. Science. 2011;332:923–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1207552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narita M, Young AR, Arakawa S, Samarajiwa SA, Nakashima T, Yoshida S, et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science. 2011;332:966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1205407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiavarina B, Whitaker-Menezes D, Migneco G, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Howell A, et al. HIF1-alpha functions as a tumor promoter in cancer associated fibroblasts, and as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer cells: Autophagy drives compartment-specific oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3534–51. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiavarina B, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Witkiewicz AK, Birbe RC, Howell A, et al. Pyruvate kinase expression (PKM1 and PKM2) in cancer-associated fibroblasts drives stromal nutrient production and tumor growth. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:12. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.12.18703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Howell A, Pestell RG, Tanowitz HB, Sotgia F, et al. Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in cancer: integrating autophagy and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kojima Y, Acar A, Eaton EN, Mellody KT, Scheel C, Ben-Porath I, et al. Autocrine TGF-beta and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) signaling drives the evolution of tumor-promoting mammary stromal myofibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013805107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ding Y, Kim JK, Kim SI, Na HJ, Jun SY, Lee SJ, et al. TGF-beta1 protects against mesangial cell apoptosis via induction of autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37909–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowak G, Schnellmann RG. Autocrine production and TGF-beta 1-mediated effects on metabolism and viability in renal cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F689–97. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]