Abstract

GATA1 is a hematopoietic transcription factor essential for expression of most genes encoding erythro-megakaryocytic proteins, i.e., globins and platelet glycoproteins. A role for GATA1 as a cell proliferation regulator has been proposed, as some of its bona fide targets comprise global regulators, such as c-KIT or c-MYC, or cell cycle factors, i.e., CYCLIN D or p21CIP1. In this study, we describe that GATA1 directly regulates the expression of replication licensing factor CDC6. Using reporter transactivation, electrophoretic mobility shift and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, we show that GATA1 stimulates CDC6 transcription by binding to a canonical binding site located within a 166bp enhancer region upstream CDC6 promoter. This evolutionary conserved GATA binding site conforms to recently described chromatin occupancy rules, i.e., preferred bases within core WGATAR (TGATAA), 5' and 3' flanking bases (GGTGATAAGG) and distance to the transcription initiation site. We also found adjacent conserved binding sites for ubiquitously expressed transcription factor CP2, needed for GATA activity on CDC6 enhancer. Our results add to the growing evidence for GATA1 acting as a direct transcriptional regulator of the cell cycle machinery, thus linking cell proliferation control and specific gene expression programs during lineage differentiation.

Keywords: CDC6, CP2, GATA1, GATA1s, megakaryocytes, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Many genes encoding factors involved in cell proliferation are regulated during specific cell-cycle phases. Among them, the expression of genes needed for G1/S transition depends almost exclusively on E2F transcription factors activity. This relies, in turn, on cyclins D-cdk4/6 complexes that phosphorylate the product of tumor suppressor Retinoblastoma (RB). In the hypophosphorylated form, RB protein associates to chromatin-bound E2F transcription factors, but when hyperphosphorylated, RB are released, and E2F may transactivate their target genes promoters.1,2 Global gene expression profiling and promoter occupancy analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-on-chip and ChIP-sequencing have confirmed that expression of direct cell cycle regulators (i.e., cyclins E, A and cdk2), nucleotide metabolism enzymes (thymidine kinase, dihydrofolate reductase), proteins directly implicated in DNA replication (i.e, PCNA, histone H2A, DNA polymerase α and delta) as well as licensing factors MCM 2–7 and CDC6 are regulated by E2F activity during a mitotic cell cycle.3

CDC6 is a key regulator of S phase and mitosis alternance. Both CDC6 and CDT1 are critical licensing factors that “mark” origins of replication.4 CDC6 has an additional important role in replication firing, because it is responsible for cyclin E-cdk2 binding to replication origins.5 It has also been related to leukemias that involve PML-RARA chromosomal translocations6 and other types of cancer, probably through a direct role in overreplication7 or silencing of the tumor suppressor Ink4a.8 CDC6 expression is also differentially regulated during physiological endoreplication of plants,9 and previous work in our laboratory showed that CDC6 expression is actively maintained upon cell cycle exit following terminal megakaryocytic polyploidization.10 This endoreplication-related expression appears to be independent on E2F binding sites. Furthermore, it can be inhibited by overexpression of the snail homolog Escargot, dependent on the presence of its consensus binding site (GCAGGTG) at -3535/-3529 of the human CDC6 gene.11 Previously, we found a consensus GATA1-binding site overlapping this E2box (GCAGGTGATAA) that suggested a putative role for GATA1 in CDC6 expression.12

GATA1 is the founder member of the GATA family of zinc finger transcription factors essential for erythroid and megakaryocytic development. Initially identified as a protein that binds cis-regulatory elements of the β-globin gene, it has since been shown to regulate a vast number of specific erythro-megakaryocytic genes13,14 or hematopoietic proto-oncogenes, such as c-MYC and c-MYB.15,16

GATA1 has two zinc finger domains: the carboxylic binds DNA at the consensus (T/A)GATA(A/G),17,18 while the amino recognizes certain double GATA sites and prefers GATC core motifs.19,20 GATA1 also cooperates with master hematopoietic regulator Scl/Tal1 at composite sites containing (CANNTG)-WGATAR sequences.21,22 However, simple identification of putative single double, or composite GATA binding sequences, even when phylogenetically conserved, is a poor predictor of their use by GATA1. In fact, only a small fraction of the in vitro characterized binding sites are actually occupied, according to various independent genome-wide occupancy analysis.21-23 These reports have defined with further precision GATA1 preferred binding motif and unveiled a rich collection of targets that suggests a more global action of GATA 1 that would affect not only the lineage-specific program, but also cell processes such as signaling and cell cycle control.

We aimed to further characterize the GATA binding domain within human CDC6 gene. Here we show that the A/TCANNTGATAA sequence at -3525/-3535 is phylogenetically conserved and appears to contain a bona fide GATA1 binding site. We also show that exogenous GATA1 transactivates CDC6 expression in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells, and that it binds a 166bp enhancer of CDC6 5'-upstream region containing the GTGATAAG(G/A) chromatin occupancy canonical motif.

Results

Ectopic GATA1 stimulates endogenous CDC6 expression in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells

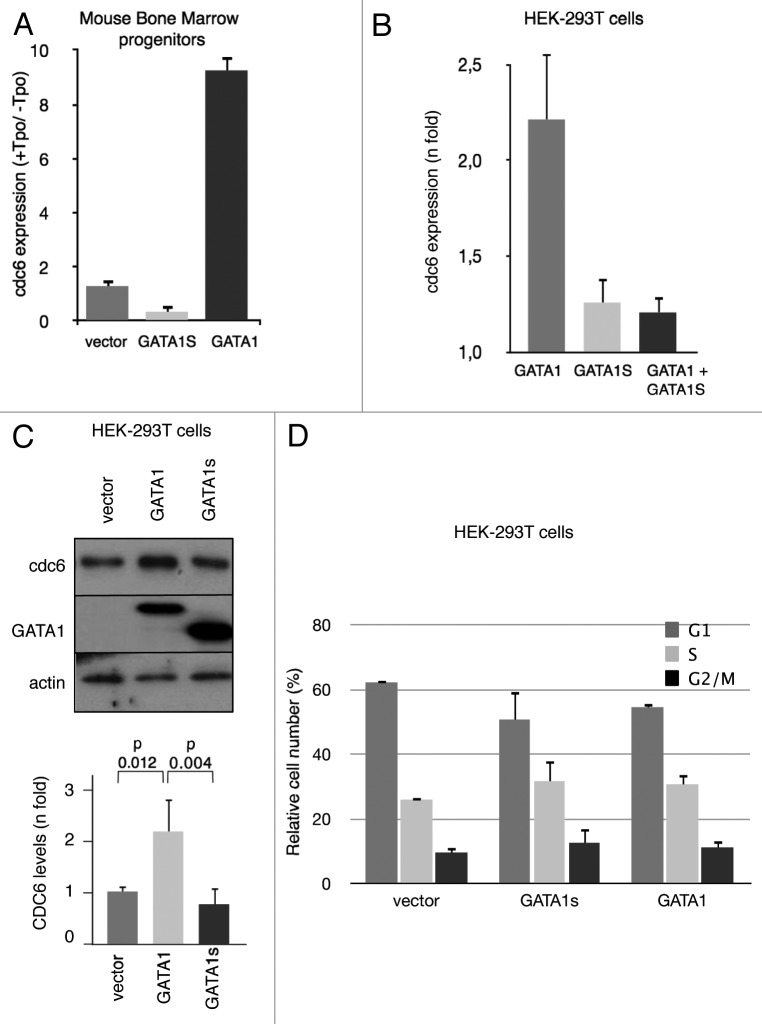

Previously, we found that CDC6 transcription was maintained during human cell lines megakaryocytic polyploidization depending on an enhancer region containing a GATA1 binding site.12 We reasoned that if GATA1 affects CDC6 transcription, ectopic expression of the transcription factor would result in increased CDC6 mRNA levels. We determined by qRT-PCR CDC6 transcript levels in sorted GFP+ primary murine hematopoietic progenitors transduced with retroviral particles containing GATA1-IRES-GFP or IRES-GFP (control) bicistronic vectors (Fig. S1) and treated with TPO to assure megakaryocytic differentiation. As shown in Figure 1A, CDC6 RNA levels increased in TPO-treated compared with untreated GATA1-expressing cells (9.25 ± 0.5-fold). In contrast, ectopic truncated GATA1s, which lacks the N-terminal transactivation domain and impairs terminal differentiation, resulted in much lower CDC6 induction in TPO-treated compared with untreated progenitors (0.4 ± 0.2-fold), whereas only a little induction was obtained in cells transduced with empty vector (1.3 ± 0.3-fold). We then asked whether ectopic expression of GATA1 in a non-hematopoietic cells would also result in an increased CDC6 expression. We thus transiently transfected HEK293T cells with expression vectors containing GATA1 or GATA1s. As can be seen in Figure 1B, CDC6 RNA levels significantly increased in GATA1-expressing but not in GATA1s-transfected cells when compared with mock transfected cells. Interestingly, co-expression of GATA1s greatly inhibited GATA1-induced CDC6 expression, underlining the potential dominant-negative effect of GATA1s. GATA1-dependent increase in CDC6 expression could also be seen at the protein level (Fig. 1C). This increase in CDC6 levels could not be attributed to an alteration in cell cycle distribution, i.e., an accumulation in G1/S, since no major differences could be detected between GATA1- and GATA1s-expressing cells (Fig. 1D; Fig. S2). These data strongly suggest that GATA1 directly affects CDC6 expression.

Figure 1.CDC6 mRNA and protein levels are increased in the presence of GATA1 in hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. (A) CDC6 relative mRNA levels in GFP+ murine hematopoietic progenitors sorted after two rounds of transduction with retroviral particles containing GATA1, GATA1s or empty bicistronic vectors and cultured for five more days (up to day+8 after isolation) in the absence (-) or the presence (+) of Thrombopoietin (Tpo). Values represent the ratio between CDC6 expression in treated (+Tpo) to untreated (-Tpo) cells, as quantified by qRT-PCR. (B) CDC6 mRNA levels in human non-hematopoietic HEK-293T cells transfected with pCDNA3-GATA1, pcDNA3-GATA1s or a mixture of both pcDNA3-GATA1 and pcDNA3-GATA1s. Values represent CDC6 expression in transfected cells with GATA1 containing vectors relative to levels in empty pcDNA3-transfected cells. (C) CDC6 protein levels in HEK-293T cells transfected with pcDNA3-GATA1 or pcDNA3-GATA1s. Panel shows a representative western blot. Histogram shows mean values ± SD of scanned band density of three independent experiments. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test. (D) Histograms showing cell cycle distribution, i.e., Propidium Iodide-labeled DNA content, of HEK-293T cells analyzed in panel (C). n = 3.

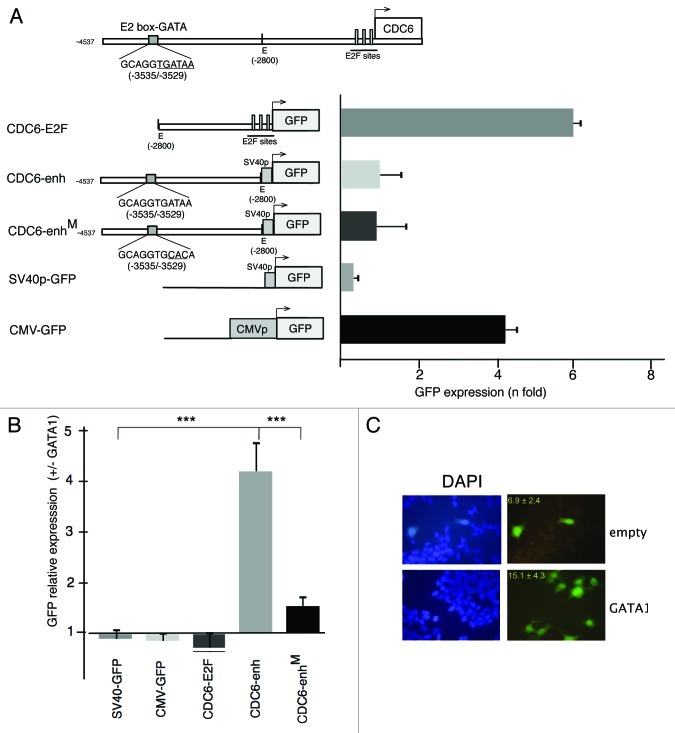

We then aimed to determine whether GATA1 was able to directly stimulate CDC6 transcription. This gene cell cycle-dependent expression is due to two E2F binding sites located in close vicinity of the transcription initiation site (-43/-36 and -8/-1) and responsible for the transcriptional activity of the entire 4.5 Kb 5' untranscribed region in proliferating cells.24-26 In contrast, the enhancer activity relevant to megakaryocytic endocycles lies in a distant region, at about 3.5 Kb upstream transcription initiation site.12 Because all hematopoietic cells lines that differentiate toward megakaryocytes already express GATA1, it is difficult to assess its direct effect on a potential non-hematopoietic target. In addition, in other hematopoietic lineages, GATA1 ectopic expression strongly affects differentiation and, hence, proliferation rates. We thus decided to determine if GATA1 was able to directly transactivate CDC6 expression in a GATA1 non-expressing cell line. We transiently transfected different GFP and/or luciferase reporter constructs carrying different portions of CDC6 5' non-transcribed region in the non-hematopoietic human HEK293T (Fig. 2A; Fig. S3A). As expected, a 2.8 Kb proximal region (containing E2F sites, CDC6-E2F) drove GFP expression (Fig. 2B) to a similar extent than that obtained with a strong viral promoter (CMVp) or the entire 4.5 Kbp 5' intergenic region.12 In contrast, almost no expression could be detected under minimal SV40 promoter (SV40p in Fig. 2A and pGL2p in Fig. S3A). Interestingly, when the 1.7 Kbp distant region (CDC6-enh) was placed upstream SV40p, a modest increase in reporter expression could be detected (Fig. 2A). However, when cells were co-transfected with an expression vector containing GATA1 cDNA, transactivation of GFP expression was only observed in CDC6-enh, but not in cdc-E2F or CMV-GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 2B). No apparent differences in morphology or cell density could be detected between cells transfected with GATA1-expressing pcDNA3 or empty vector (Fig. 2C), thus differences in GFP expression could only be due to GATA1 activity. Furthermore, transactivation was abolished when GATA1 binding site was mutated (CDC6-enhM), indicating that the 1.7 Kb distant region contained an enhancer stimulated by GATA1.

Figure 2. GATA1 induces transcriptional enhancer activity of a CDC6 untranscribed distal region (-2800/-4547). (A) Upper diagram represents CDC6 untranscribed region as described in ref. 25 and shows essential cell cycle-dependent E2F functional sites and the polyploidization-related enhancer sequence (CDC6-enh, ref. 12) containing GATA1 binding site (underlined). Lower diagrams correspond to different constructs used for transfecting HEK-293T cells and analysis of reporter gene (GFP). The arrow indicates the transcription initiation site. E = EcoRI indicates the restriction enzyme used to isolate distal region. Histogram represents mean GFP expression ± SD relative to cells transfected with the empty vector (n = 4). Transfection effciciency was normalized by cotransfecting with Renilla luciferase expression pCMV vector. (B) Constructs depicted in (A) were co-transfected with empty pcDNA3 vector (-GATA1) or pcDNA3-GATA1 (+GATA1). Histograms represent mean GFP expression ± SD of GATA1 transfected relative to mock transfected cells. n = 9, except for CDC6-E2Fan (n = 4). *** indicate p values < 0.0001 (0.0000000887 and 0.000000669, left and right, respectively), calculated using Student’s t-test. (C) Fluorescence microphotography shows a representative field of co-transfected cells with CDC6-enh construct and empty or GATA1 containing pcDNA3 vector, two days after transfection. Inset values represent the mean percentage ± SD of GFP+ cells in four fields containing 105 ± 12 and 110 ± 22 cells transfected with empty or GATA1 containing pcDNA3 vector, respectively, as visualized by DAPI staining.

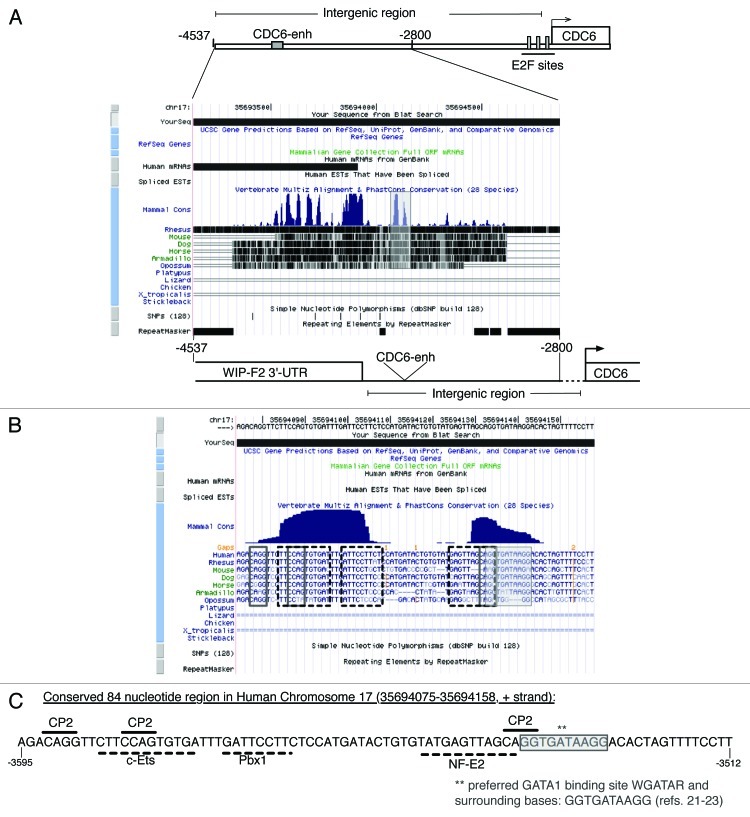

A new GATA1 binding site is present in a highly conserved intergenic region upstream CDC6, also containing erythroid-associated tandem CP2 binding sites

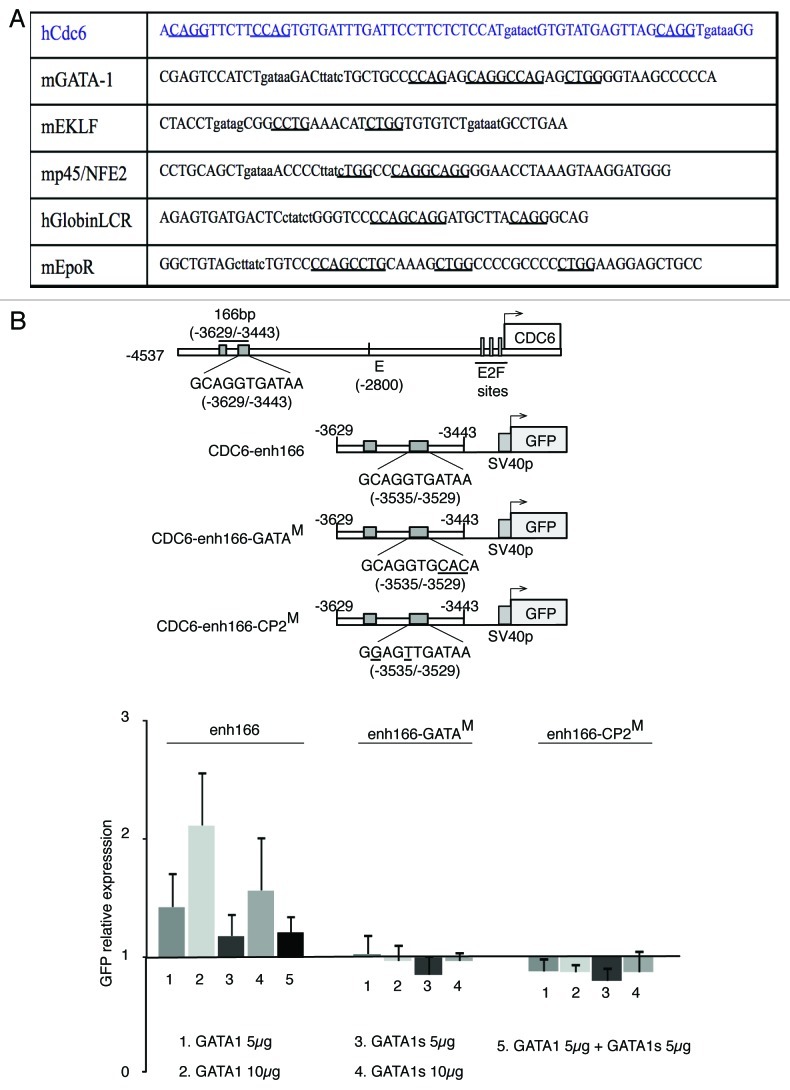

We further analyzed the genomic region containing this GATA1 binding site in intergenic sequences 5' to CDC6. We compared the 5' untranscribed regions of CDC6 genes from different species equivalent to the 1.7 Kb (-4548 to -2798 of the human gene) containing the GATA1-responsive enhancer in the human gene. As can be seen in Figure 3A, the GATA1 site at -3530 bp was part of the two most prominent highly conserved segments within the intergenic region between CDC6 and WAS-WASLIP 3' end (-3700 bp relative to CDC6 transcription initiation site). Within the most 3' intergenic homology region (right peak), the WGATAR motif was equally conserved in mammals, as well as a proximal NF-E2 binding motif (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the second highly conserved segment (left peak) contained binding sites for different transcription factors relevant to hematopoietic cells, such as c-ets and pbx1. At least two of these conserved sites, those bound by c-ets and NF-E2, have been related to megakaryocytic differentiation.27-29 Interestingly too, four CP2 binding sites were found in this 100 bp region, one of them being adjacent to GATA1 binding site (Fig. 3C), in a similar position as in other previously described regulatory regions of GATA1 controlled genes (Fig. 4A and ref. 30).

Figure 3. In silico analysis of CDC6 untranscribed distal region . Multiple alignment (UCSC Genome Browser) of CDC6 upstream region in chromosome 17 (35693125 to 35694875, + strand) expanding from -4548 to -2798 upstream CDC6 transcription initiation site (35694075 to 35694144). The non-to scale diagrams of CDC6 upstream region analyzed in Figure 2 (upper) and of the analyzed region (lower) including the mRNA upstrem CDC6-enh are shown for easy location purposes. The shaded box in panel (A) frames two homology peaks, the right one containing the GATA1 binding site within CDC6-enh sequence, at -3535 to -3529 relative to initiation transcription site, described in Figure 2 and highlighted in panel (B) with the gray box. Also framed are conserved sequences within the 85 bp region which sequence and putative CP2 (plain line) or other hematopoietic (dotted line) transcription factors binding sites are detailed in (C). Positions relative to CDC6 transcription start site are shown.

Figure 4. 166bp region is sufficient to respond to GATA1 depending on the integrity of both GATA1 and CP2 binding sites. (A) Table showing GATA1 and CP2 binding sites in CDC6 enhancer region described in this paper and selected GATA1 regulated erythroid genes as shown in ref. 30 (B) Upper diagrams: reporter construct diagrams showing the 166 bp region within CDC6 enhancer distal region containing intact GATA1 and CP2 binding sites and the corresponding single derived mutated versions (changed nucleotides are underlined). Lower graph: Histograms show mean GFP expression ± SD in HEK293-T cells transfected with the indicated reporter constructs together with the indicated amounts of pcDNA3-GATA1 or GATA1s. Values are relative to GFP expression in mock transfected cells and normalized by cotransfecting with renilla pCMV vector.

We asked whether the small region containing CP2/GATA1 binding sites is important for the activity of this GATA1-dependent distal 1.7 Kb enhancer. As can be observed in Figure 4B, ectopic expression of GATA1 in HEK293T cells resulted in GFP expression in a dose- and functional integrity-dependent manner. Mutations that abolished GATA1 binding, or concomitant expression of dominant-negative GATA1s also resulted in decreased transactivation. Interestingly, when CP2 site was disrupted, GATA1 transactivation equally decreased, indicating that this binding site may be important for GATA1 function. Endogenous CP2 is able to interact with GATA1 (Fig. S4 and ref. 30), suggesting a functional interaction between both transcription factors.

These results, together with the fact that ectopic GATA1 expression increased CDC6 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1B and C), indicate that CDC6 expression is induced by GATA1 in non-hematopoietic cells. They also point at a 160 bp region containing binding sites for other transcription factors relevant to erythro-megakaryocytic differentiation, especially CP2, as an important GATA1-responsive cis-regulatory element.

GATA1 binds CDC6 5' untranscribed distal region in vitro and in vivo

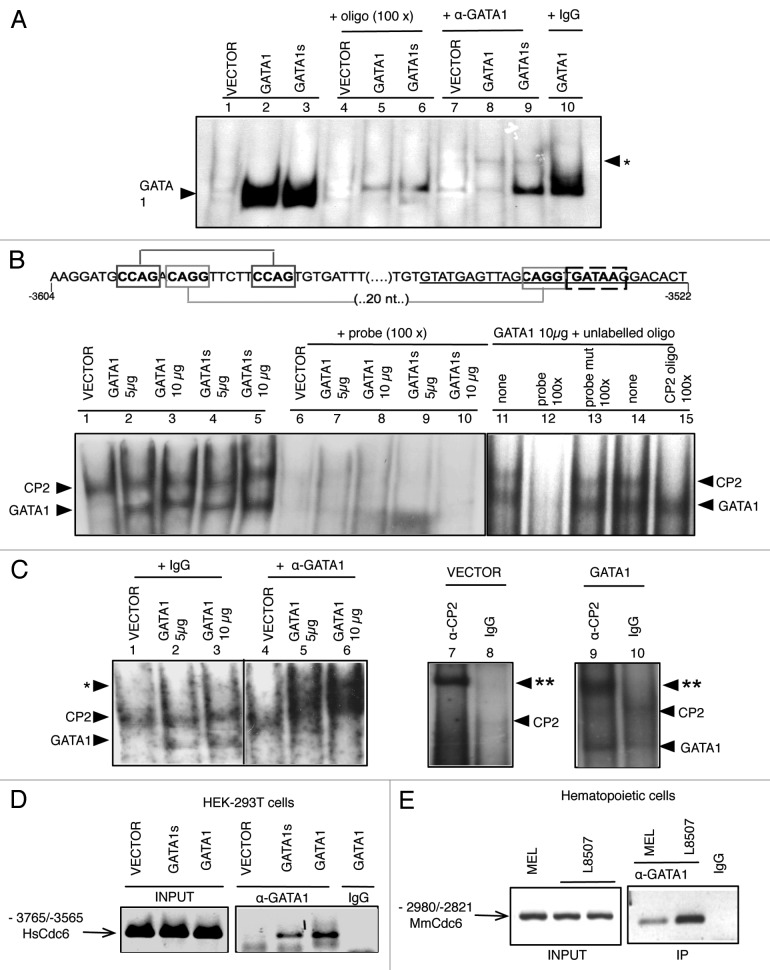

To test if GATA1 directly regulates CDC6 transcription, we investigated if the pertinent CDC6 region was bound by GATA1. We first performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays with nuclear extracts from 293T cells transfected with GATA1 or GATA1s and an oligonucleotide spanning the 3' conserved segment described in Figure 3B. As expected, both GATA1 and GATA1s were able to bind the oligonucleotide containing the GATA1 site responsible for CDC6 transactivation (Fig. 5A). This also occurred with GATA1-expressing erythro-megakaryocytic extracts.12 The binding was specific as demonstrated by competition with the corresponding unlabeled competitor oligonucleotide (Fig. 5A, lanes 5–6) or the presence of a supershifting antibody, although this was most effective in GATA1-expressing cells (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 8 and 9).

Figure 5. GATA1 binds in vitro and in vivo to the 166bp region of human and murine CDC6 gene. (A) Nuclear extracts from HEK293T cells transfected with pcDNA3 vector empty or containing GATA1 or GATA1s, incubated with labeled oligonucleotide (short GATA1 probe) containing GATA1 and one CP2 binding sites (-3545/-3529), in the absence (1–3) or in the presence (4–6) of excess unlabelled oligonucleotide, anti-GATA1 antibody (7–9) or isotype matching IgG (10) were analyzed by EMSA. Goat polyclonal anti-GATA1 antibody (C20, Santa Cruz) results in a supershift of GATA1-containing complexes (labeled as *). (B) Diagram of 84 nt long oligonucleotide containing GATA1 and tandem CP2 binding sites in distal CDC6 upstream region (probe). Positions relative to CDC6 transcription start site are shown. EMSA of GATA1, GATA1s or mock transfected HEK293T cells nuclear extracts incubated with labeled long oligonucleotide in the absence or the presence of excess (100 times) unlabelled competing oligos as indicated. Competing oligos: 84 nt probe (probe, lanes 6–10 and 12), 84 nt probe mutated in CP2 and GATA1 binding sites (probe mut, lane 13), bona fide CP2 binding oligonucleotide corresponding to HS2 enhancer30 (CP2 oligo, lane 15). (C) EMSA of nuclear extracts as in (B), but incubated with antiGATA1 and anti-CP2 antibodies as indicated. As in (A), goat polyclonal anti-GATA1 antibody (C20, Santa Cruz), but not goat IgG, results in a supershift of GATA1-containing complexes (labeled as *, lanes 5 and 6 vs. 2 and 3). CP2-containing complexes are supershifted (labeled as **, lanes 7 and 9) with rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abnova), but not with IgG (lanes 8 and 10). (D) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed using fragmented cross-linked chromatin from mock, GATA1 or GATA1s transfected HEK293T cells and anti-GATA1 antibody or isotype IgG. One-sixth of total purified DNA was amplified by PCR with primers specific to distal CDC6 intergenic region containing GATA1 and tandem CP2 binding sites (-3709/-3565). (E) ChiP assay as in (D) but performed with chromatin from murine megakaryoblastic L8057 and erythrocytic MEL cells and primers for mouse Cdc6 distal 5' intergenic region (-2980/-2821). For both (D and E), PCR reactions were also performed using the fragmented chromatin purified prior to antibody incubation (input).

We also performed similar experiments using a larger oligonucleotide in order to include both conserved segments and the two CP2 tandems within as depicted in Figure 5B. As can be seen, two complexes could be detected: one corresponding to GATA1 (only detectable in GATA1-transfected 293-T cells); a second one present in nuclear extracts from both cells transfected with empty or GATA1-containing vector (Fig. 5B and C). Both complexes were specific, as shown by total competition with unlabelled oligonucleotide (Fig. 5B, lanes 6–10 and 12). The slower migrating band that could correspond to CP2, as previously assessed30 was also specifically competed with an excess of unlabelled bona fide CP2 binding oligonucleotide (Fig. 5B, lane 15). Interestingly, when anti-GATA1 antibody was added to the reaction, both complexes were supershifted in GATA1-expressing nuclear extracts (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 and 6) but not CP2 complex in mock-transfected cells (Fig. 5C, lane 4). This CP2 complex was also supershifted in the presence of anti-CP2 antibodies not only in cells transfected with the empty vector (Fig. 5C, lane 7), but also in GATA1 expressing cells (Fig. 5C, lane 9).

Finally, we asked whether GATA1 was present at the CDC6 enhancer conserved regulatory region in GATA1-expressing cells. We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments with a GATA1 antibody and crosslinked chromatin from transfected 293T cells (Fig. 5D) as well as from murine erythrocytic and megakaryocytic cells (Fig. 5E). We found GATA1 enrichment in the region that contains the CP2 tandems and GATA1 binding site, consistent with stable association to these sequences in all GATA1-containing cells.

Altogether, these results indicate that GATA1 binds the CDC6 regulatory region in vitro and in vivo. They strongly suggest that this tissue-specific transcription factor directly regulates CDC6 expression in erythro-megakaryocytic cells.

Discussion

In this paper, we present data consistent with CDC6, a replication-licensing factor, being a direct target of GATA1. This reinforces previous evidence of our lab that proposed that the expression of this replication licensing factor is specifically regulated during megakaryocytic terminal maturation.10,12 Our results also validate the finding that CDC6 may be a real target of GATA1, as revealed by genome-wide chromatin occupancy data in mouse cells.21

Ectopic expression of GATA1 results in increased levels of cdc6, not only in primary hematopoietic progenitors, but also in heterologous 293T cells. This may be somewhat surprising, as GATA1 transcriptional activity is functional in cells distant from the erythro-megakaryocytic lineages, not only on the exogenous reporter construct, but also on the endogenous locus. It could be argued that the expression of a cell cycle-regulated gene may be a consequence of the proliferation status of the analyzed cells: changes in cell cycle distribution can result in changes in cell cycle-dependent factors. However, GATA1 and GATA1s lead both to similar changes in cell cycle profiles compared with mock-tranfected cells, but only GATA1 increases CDC6 levels. This is reminiscent of the effect that ectopic GATA1 is able to increase expression of globin or p21cip1 in epithelial HeLa cells.31,32

Sequence features of in vivo GATA1-bound site at distal CDC6 enhancer suggest that it is a bona fide cis-regulatory element. First, the core WGATAR sequence and flanking 5' and 3' bases GGTGATAAGG appears to comply with the recently described as preferentially in vivo occupied GATA1 binding sequences. Thus, being the basic WGATAR consensus sequence the core of the protein recognition,33 the W appears to be almost equally represented in vivo by T or A (with slight preference for the latter), but the R is vastly an A. Also, the surrounding bases appear to follow a preference pattern, and C/G precedes the W, while a G preferentially follows the final A.21-23 Second is that GATA1-regulated region is located at more than 3,000 bp upstream CDC6 promoter and functions as an enhancer when placed with a minimal promoter, in agreement with the observation that 90% of the sites occupied in vivo are located in enhancers or introns (47% and 37%, respectively). This suggests that GATA1 mostly functions as a long-range trans-acting rather than as a local, promoter-proximal regulator such as E2F proteins34. In addition, the GGTGATAAGG site in cdc6 enhancer is juxtaposed to several CP2 sites. In fact, the guanosines at the 5' end are part of one of the CNRG (CAGG) CP2 canonical site. Furthermore, two conservation regions lie within the166bp enhancer region: the one in the 3‘end contains the CP2-GATA1 already described; the second, 40 bases upstream, contains a second tandem of CP2 sites (CAGGttcttCCAG). This organization as tandem sites seems to be a feature of a significant number of GATA1-regulated genes, among them, the HS2 region of autoregulated GATA1 gene, in which all CP2 sites seem to be essential for GATA1 function.30

The idea that GATA1 may have a functional role in CDC6 transcription is based in different lines of evidence: (1) a 166 bp CDC6 distant upstream region is strongly stimulated by ectopic expression of GATA1 in heterologous cells, as shown in reporter assays. This region also has enhancer activity in hematopoietic cell lines that express GATA1, such as erythro-megakaryocytic HEL and K562 cells;12 (2) GATA1 binds in vitro to this region that is highly conserved in mammals and contains a mostly preferred GATA consensus binding site together with other conserved CP2 sites also found in other GATA1 targets;30 (3) GATA1 is bound in vivo to the CDC6 upstream region containing this binding site, not only when ectopically expressed in non-hematopoietic cells, but also in the endogenous locus of murine and human erythro-megakaryocytic cell lines (this paper, refs. 12, 21 and 22). This suggests that CDC6 expression may be regulated differentially via E2F or GATA1 depending on cell type and proliferation/maturation stage context. This is reminiscent of the dual regulation mechanisms of other cell cycle factors, such as cyclin D1, whose transcription depends on GATA1 only in megakaryocytic differentiation35 or on cytokine-induced STAT5 in proliferating cells only.36 On the other hand, CDC6 transcription is controlled by generic E2F factors during cell proliferation24,26 but it is also regulated by tissue-specific transcription factors, as recently shown for MyoD during muscle terminal differentiation.37,38 It seems then that CDC6 may be one important player in the balance of lineage-specific proliferation status, cell cycle exit and final maturation.

The results reported here are in line with other reports that suggest that GATA1 is a direct cell cycle regulator,15,21 but GATA1 is primarily defined as a paradigmatic lineage-instructive regulator required for proper homeostasis of erythrocytes and megakaryocytes. In fact, transcriptional control of most of these lineages genes has been shown to depend on GATA1 activity.15,21,22,39,40 However, final differentiation and maturation of these cells is accompanied by changes in cell proliferation and therefore in cell cycle status: megakaryocytic maturation is characterized by entrance into endoreplication cycles, and final erythroid differentiation needs GATA1-mediated proliferation arrest.41 Also, GATA1 inhibits cell proliferation through control of many genes involved in cell cycle regulation, as revealed by microarray expression analysis15 and, more significantly, by ChIP-seq approach.21,22 Among the identified putative cell cycle targets, E2f4 and Nek6, together with CDC6 are under direct control of GATA1. Most significantly, p21 has recently been shown to be directly regulated by GATA1.32 It seems then that transcriptional programs involved in determination and cell differentiation could directly affect cell cycle status. A paradigmatic example is the MyoD directed program, very early on described to directly regulate p21,42 and, as mentioned, also CDC638 when satellite cells are re-entering cell cycle. Another example is GATA1-induced megakaryocytic endoreplication, the entrance into a special cell cycle that needs maintenance of CDC6 and other cell cycle regulators expression in the absence of proliferation.10,35

We suggest that regulated CDC6 expression during cell differentiation, as documented in muscle,38 erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages10,15,32 and prostate cancer cells43 is the outcome of the coordinated action of E2F proteins linked to mitotic cell cycles and of tissue-specific transcription factors such as MyoD, GATA1 or androgen receptor.

Material and Methods

Plasmids

Reporter constructs CDC6 enhancer-GFP(-4537/-2800), CDC6-E2F-GFP(-2800) and CDC6 enhancer-GATAM-EGFP were generated from pGL2 promoter-based pHscdc6(-4537/-2800), pHscdc6(-2800) and pHscdc6/-4537/2800)BGATAM 12, replacing luciferase gene with a EcoRI/XhoI fragment containing EGFP from pcDNA3-GFP. p CDC6-166 y p CDC6-166-GATAM contain the GATA1 binding motif TGATAAG upstream of a minimal SV40 promoter and GFP or luciferase reporter genes were generated by PCR amplification of a 166 bp fragment using 5'-ACAAAAGGATGCCAGACAGGT-3' and 5'-ATGGTTAGATTGGGTTGGGAA-3' oligonucleotides, subsequently cloned in pGEM-T (Invitrogen). The GATA1 binding motif and adjacent sequences were then subcloned in pcDNA3 as a EcoRI fragment and finally inserted as a KpnI/XhoI fragment into pGL2-promotor or pGFP-promotor plasmids. For retroviral bicistronic vectors containing Myc-tagged full-length and truncated GATA1 and GATA1s, GATA1 cDNA (a generous gift of Dr.Nakano, University of Osaka) was first subcloned into pCDNA3 vector then cloned into pCS2-MT vector. pLZR-MT-MT-GATA1-IRES-GFP was generated by ligating a BamHI/SalI fragment from pCS2-MT-GATA1 together with a SalI-NotI fragment containing IRES-EGFP into BamHI/SalI digested pLZR-IRES-NGFR∆.44 MT-GATA1s was obtained by digesting GATA1 cDNA with EcoRI/SalI and subcloning into pCS2-MT plasmid. pLZR-MT-GATA1s-IRES-GFP was generated as described for full-length GATA1. Point mutations were introduced with the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). The DNA sequence of all mutant and/or tag-fused cDNAs were verified accordingly.

Cell culture, transfection and retrovirus production

Human embryonic epithelial kidney cells expressing SV40 T-Antigen (HEK293-T) and NIH-3T3 cells were cultured at 37°C, 95% humidity and 5% CO2 in DMEM medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 50 U/ml Penicillin and 50 µg/ml of Streptomycin. Megakaryocytic (L8507) and erythrocytic (MEL) mouse cell lines (generously provided by Dr Mikkola) were, respectively, cultured in RPMI 1640 or DMEM medium also supplemented with FBS, glutamine and antibiotics. All reagents were purchased from Invitrogen.

For retrovirus production, cells were transiently co-transfected with the appropriate pLZR retroviral vector and pCLEco vector that expresses the ecotropic envelope protein.45 After 48 h, supernatants containing viral particles were filtered and kept at -70°C until use.

Bone marrow progenitor isolation and transduction

Bone marrow was obtained by flushing both femurs and tibiae with phosphate buffered saline containing 2% fetal calf serum (PBS/2% FCS) under sterile conditions. Lin- cells were prepared by using a Lineage Cell Depletion Kit and LD columns together with a QuadroMACS™ separation unit from Miltenyi Biotec. Cells were cultured overnight in IMDM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine and antibiotics, and 10 µg/ml of each IL3, IL6 and SCF (Peprotech). Retroviral infection was performed by spinoculation of Lin- cells in the presence of supernatants containing retroviral particles in the presence of 1 µg of Polybrene/ml. Successfully transduced GFP-positive cells were then purified by FACS using a FacsVantage/DIVA cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For megakaryocytic differentiation, GATA1 or GATA1s transduced cells were cultured in the presence or absence of TPO (50 ng/ml, Stem Cells Technologies).

Transactivation reporter assays

Five million HEK293-T cells were plated in triplicate 4–12 h and calcium-phosphate transfected with 10 µg promoter-reporter plasmids, together with 5 µg of a renilla luciferase-expressing plamid (Promega) for normalization purposes. When appropriated, different amounts of pCDNA3 containing GATA1 or GATA1s were added. Briefly, DNA was mixed with HBS (280 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4 2 H2O) and 125 mM CaCl2 final concention. After 10 min at RT, the mix was added to the cultured cells. Cells were analyzed 48 h later for GFP expression in FACScan flow cytometer and/or lysed and assayed for luciferase and renilla activity following manufacturer instructions (Dual Luciferase kit, Promega).

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was isolated by lysing the cells in Tri Reagent (Sigma), quantified in a Nanodrop device and analyzed for its integrity (Agilent Bioanalyser). If not used at once, RNA was stored in 70% EtOH at -70°C. 5 µg was reverse-transcribed with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) using random primers and a SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). A qPCR analysis was performed in three replicates using the cDNA from 150 ng RNA per reaction in an iQ5 or a Stratagene’s Mx3005P thermal cyclers with SYBR-Green based mixes. Gene expression data were analyzed with iQ5 software (Bio-Rad) or MxPro ET Software (Agilent). Sequences of primer pairs for qPCR: HsCDC6 direct: 5'-GTCCCCCTCACTCACATACACT-3'; HsCDC6 reverse: 5'-CCTCTTCCTGACAAATCTCCTG-3' MmCdc6 direct: 5'-ACGTCTGGGCGATGACAAC-3' MMCcd6 reverse: 5'-TTGGTGGAGAACAGGGAGATAAC-3'

Western blotting analysis

Cells were lysed for 30 min on ice in RIPA buffer (10 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl. 1% TX-100, 0,1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaF, 100 μM orthovanadate and protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min, aliquoted, snap-frozen and kept at -70°C until used. Thirty micrograms of total protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE and transferred to BioTrace polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Pall Corporation) for 45 min at 2 mA/cm2 on a semidry transfer apparatus (Amersham). Ponceau staining was routinely performed on membranes, and digital photographs were taken in order to record a sample loading control. After blocking in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat dry milk, filters were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-Cdc6 (Ab3; Oncogene, 1:200), anti-GATA1 (C20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:500) and anti-β-actin (Sigma, clone AC-15). After a washing step and incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako), signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce).

Nuclear extracts

Ten to 15 million cells were collected by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in 500 µl of Buffer A (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9 containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT and proteases/phosphatases inhibitors; after incubation for 10 min at 4°C, 200 µl of 0.5% NP40 in Buffer A were added and incubation resumed for other 10 min. After centrifugation for 10 min at 2,000 rpm at 4°C, pellet was resuspended in 150 µl of hypertonic Buffer B (20mM HEPES pH 7.9 containing 25% Glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5 mM DTT and proteases/phosphatases inhibitors. After incubation at 4°C for 30 min, nuclear lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected, snap frozen and stored at -70°C.

Mobility gel shift analysis

EMSA was performed essentially as described previously,12 with 0.02 pmol of [32P]-labeled oligoprobe and 20µg of nuclear extracts. The following partially complementary oligonucleotides were used to generate double stranded oligoprobes: short GATA1 probe: 5'-GTATGAGTTAGCAGGTGATAAG-3' 5'-AGGTCCTTATCACCTGCTAACT-3' long CP2 tandem/GATA1 probe: 5'AAGGATGCCAGACAGGTTCTTCCAGTGTGATTTGATTCCTTCTCCATGATACTGTGTATGAGTTAGCAGGTGATAAG-3' 5'AGTGTCCTTATCACCTGCTAACTCATACACAGTATCATGGAGAAGGAATCAAATCACACTGGAAGAACCTGTCTGGC -3' (long CP2 tandem/GATA1) long CP2 tandem/GATA1 mutated probe: long CP2 tandem/GATA1 mutated in the underlined GATA1 (GATAA to CACAA) and CP2 (CCAG to TAAG and CAGG to TAGG) binding sites. Bona fide CP2 binding site in HS2 enhancer region of GATA1 gene, GATA695–660 CP2 site as in:30 5'-CTGCTGCCCCAGAGCAGGCCAGAGCTGGCGTAAGC-3' 5'-GCTTACGCCAGCTCTGGCCTGCTCTGGGGCAGCAG-3'

Binding reactions were performed for 20 min at room temperature in binding buffer (20% glycerol, 1mM dithiothreitol, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl and 0.4 mM EDTA) containing 0.02 pmol of [32P]-labeled oligoprobe, 20 µg of protein extracts as indicated, and 40 µg/ml poly(dI-dC). When needed, competitor oligoprobes were added in excess (100×) to the binding reaction. For supershifts, 2 μl of anti-GATA1 (C-20 Santa Cruz), anti-CP2 rabbit polyclonal from Abnova) or the equivalent amount of goat or rabbit IgG were incubated with the nuclear extracts for 2 h at 4°C before the addition of the radiolabelled probe. DNA-protein complexes were separated from unbound labeled oligoprobes on 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in Tris Borate/EDTA buffer. After drying, the shifted complexes were visualized by autoradiography.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

The procedure was performed as previously described12 with some modifications. Briefly, cells were lysed first in 1% NP-40 containing Buffer (15 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT 15 mM NaCl and 300 mM Sucrose), then in 1% SDS Buffer (20 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA and 1× complete antiprotease cocktail from Roche). The lysate was then sonicated in a Bioruptor (Diagenode, Inc.), under conditions that yielded DNA fragment sizes of 200–1000 bp. Sonicated chromatin was then diluted in immunoprecipitation Buffer (1.1% TX100 and 0.1% SDS in 16.7 mM TRIS-HCl pH 8.0, 1.2 mM EDTA and complete protease cocktail). Protein-G Sepharose (Pierce or Fisher) was used for pre-clearing and collection of immunocomplexes after incubation overnight at 4°C with 2 µg antibody (anti-GATA1, rat monoclonal N6 or goat polyclonal C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, or the corresponding non-immune isotype immunoglobulins from Sigma). Following extensive washing, elution in 1% SDS in TE Buffer, crosslinking reversion and RNase/proteinase K treatment, extracted DNA was resuspended in 30 μl water/107 cells. Immunoprecipitated chromatin (2 µl) and the equivalent to 1/1,000 of the input fraction (total chromatin used for the immunoprecipitation) was used for each PCR reaction (40 cycles of 30 sec. at 94°C; 30 sec. at 56°C; 30 sec at 72°C and one last cycle of 10 min at 72°C), containing 25 pmol of each direct and reverse primers. The following primers were used: 5'-ACAAAAGGATGCCAGACAGGT-3'; 5'-ATGGTTAGATTGGGTTGGGAA-3' -for human site- 5'-TCCAGTGTGACTTGATTCCTGC-3'; 5'-TCACAAGCAAGAGGAAGGTAGC-3' -for mouse site- PCR products were separated in a 1.5% TBE-agarose gel and DNA was visualized by Ethidium Bromide staining.

IP-western assay

Nuclear extracts (100 µg) were precleared by incubation with 100µl of Protein-G Sepharose (50% in IP buffer: 20 mM Tris, pH 7.8; 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM KCl; 0.5 mM EDTA containing 1 µg/ml BSA, 0.1% NP40, 5 mM b.+-mercaptoethanol and 20% glycerol) for one hour at 4°C. Supernatant was then split into two aliquots. One was incubated with 2 µg anti-GATA1 (goat polyclonal antibody C20, Santa Cruz), the other with the same amount of isotope matching IgG (Sigma) for 4 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were then collected with protein G beads for one hour at 4°C . After extensive washing with IP buffer, samples were analyzed by Western Blotting with rat monoclonal anti-GATA1 (N6, Santa Cruz) or mouse monoclonal anti-CP2 (BD Transduction Laboratories). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse IgG light chain antibodies (Dako) were used to detect the immunoprecipitated proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank H. Mikkola (UCLA) for generous gift of the cells and support in her lab, T. Nakano (Osaka University) for human GATA1 cDNA, A. Ronchi (University of Milan) for CP2 reagents and advice, and M. Vidal (CSIC) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work and L.P. were supported by grant BFU2008–03386/BMC from former Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN) of Spain. B.F-M was recipient of a fellowship from the “Formación de Personal Investigador” Program, also from MICINN.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ChIP

chromatin Immunoprecipitation

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IL3

Interleukin 3

- IL6

Interleukin 6

- Lin- cells

lineage-negative cells

- SCF

stem cell factor

- TPO

thrombopoietin

- WIP-F2

Wiskott Aldrich syndrome-Wiskott Aldrich syndrome-like interacting protein family member 2

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/21471

References

- 1.Chellappan SP, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell. 1991;65:1053–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodrich DW, Wang NP, Qian YW, Lee EY, Lee WH. The retinoblastoma gene product regulates progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell. 1991;67:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90181-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracken AP, Ciro M, Cocito A, Helin K. E2F target genes: unraveling the biology. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borlado LR, Méndez J. CDC6: from DNA replication to cell cycle checkpoints and oncogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:237–43. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunn CL, Chrivia JC, Baldassare JJ. Activation of Cdk2/cyclin E complexes is dependent on the origin of replication licensing factor Cdc6 in mammalian cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4533–41. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.13789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walz C, Grimwade D, Saussele S, Lengfelder E, Haferlach C, Schnittger S, et al. Atypical mRNA fusions in PML-RARA positive, RARA-PML negative acute promyelocytic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:471–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archambault V, Ikui AE, Drapkin BJ, Cross FR. Disruption of mechanisms that prevent rereplication triggers a DNA damage response. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6707–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6707-6721.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez S, Klatt P, Delgado S, Conde E, Lopez-Rios F, Sanchez-Cespedes M, et al. Oncogenic activity of Cdc6 through repression of the INK4/ARF locus. Nature. 2006;440:702–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellano MM, del Pozo JC, Ramirez-Parra E, Brown S, Gutierrez C. Expression and stability of Arabidopsis CDC6 are associated with endoreplication. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2671–86. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bermejo R, Vilaboa N, Calés C. Regulation of CDC6, geminin, and CDT1 in human cells that undergo polyploidization. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3989–4000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballester A, Frampton J, Vilaboa N, Calés C. Heterologous expression of the transcriptional regulator escargot inhibits megakaryocytic endomitosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43413–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vilaboa N, Bermejo R, Martinez P, Bornstein R, Calés C. A novel E2 box-GATA element modulates Cdc6 transcription during human cells polyploidization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6454–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitelaw E, Tsai SF, Hogben P, Orkin SH. Regulated expression of globin chains and the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 during erythropoiesis in the developing mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6596–606. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannon R, Evans T, Felsenfeld G, Gould H. Structure and promoter activity of the gene for the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3004–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rylski M, Welch JJ, Chen YY, Letting DL, Diehl JA, Chodosh LA, et al. GATA-1-mediated proliferation arrest during erythroid maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5031–42. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.5031-5042.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munugalavadla V, Dore LC, Tan BL, Hong L, Vishnu M, Weiss MJ, et al. Repression of c-kit and its downstream substrates by GATA-1 inhibits cell proliferation during erythroid maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6747–59. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6747-6759.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wall L, deBoer E, Grosveld F. The human beta-globin gene 3' enhancer contains multiple binding sites for an erythroid-specific protein. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1089–100. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans T, Reitman M, Felsenfeld G. An erythrocyte-specific DNA-binding factor recognizes a regulatory sequence common to all chicken globin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5976–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newton A, Mackay J, Crossley M. The N-terminal zinc finger of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 binds GATC motifs in DNA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35794–801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trainor CD, Omichinski JG, Vandergon TL, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM, Felsenfeld G. A palindromic regulatory site within vertebrate GATA-1 promoters requires both zinc fingers of the GATA-1 DNA-binding domain for high-affinity interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2238–47. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu M, Riva L, Xie H, Schindler Y, Moran TB, Cheng Y, et al. Insights into GATA-1-mediated gene activation versus repression via genome-wide chromatin occupancy analysis. Mol Cell. 2009;36:682–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara T, O’Geen H, Keles S, Blahnik K, Linnemann AK, Kang YA, et al. Discovering hematopoietic mechanisms through genome-wide analysis of GATA factor chromatin occupancy. Mol Cell. 2009;36:667–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng Y, Wu W, Kumar SA, Yu D, Deng W, Tripic T, et al. Erythroid GATA1 function revealed by genome-wide analysis of transcription factor occupancy, histone modifications, and mRNA expression. Genome Res. 2009;19:2172–84. doi: 10.1101/gr.098921.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hateboer G, Wobst A, Petersen BO, Le Cam L, Vigo E, Sardet C, et al. Cell cycle-regulated expression of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on E2F. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6679–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtani K, Tsujimoto A, Ikeda M, Nakamura M. Regulation of cell growth-dependent expression of mammalian CDC6 gene by the cell cycle transcription factor E2F. Oncogene. 1998;17:1777–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan Z, DeGregori J, Shohet R, Leone G, Stillman B, Nevins JR, et al. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemarchandel V, Ghysdael J, Mignotte V, Rahuel C, Roméo PH. GATA and Ets cis-acting sequences mediate megakaryocyte-specific expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:668–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart A, Melet F, Grossfeld P, Chien K, Jones C, Tunnacliffe A, et al. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13:167–77. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shivdasani RA, Rosenblatt MF, Zucker-Franklin D, Jackson CW, Hunt P, Saris CJ, et al. Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development. Cell. 1995;81:695–704. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosè F, Fugazza C, Casalgrandi M, Capelli A, Cunningham JM, Zhao Q, et al. Functional interaction of CP2 with GATA-1 in the regulation of erythroid promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3942–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3942-3954.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Layon ME, Ackley CJ, West RJ, Lowrey CH. Expression of GATA-1 in a non-hematopoietic cell line induces beta-globin locus control region chromatin structure remodeling and an erythroid pattern of gene expression. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papetti M, Wontakal SN, Stopka T, Skoultchi AI. GATA-1 directly regulates p21 gene expression during erythroid differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1972–80. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merika M, Orkin SH. DNA-binding specificity of GATA family transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3999–4010. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bieda M, Xu X, Singer MA, Green R, Farnham PJ. Unbiased location analysis of E2F1-binding sites suggests a widespread role for E2F1 in the human genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:595–605. doi: 10.1101/gr.4887606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muntean AG, Pang L, Poncz M, Dowdy SF, Blobel GA, Crispino JD. cyclin D-Cdk4 is regulated by GATA-1 and required for megakaryocyte growth and polyploidization. Blood. 2007;109:5199–207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-059378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumura I, Kitamura T, Wakao H, Tanaka H, Hashimoto K, Albanese C, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 promoter by STAT5: its involvement in cytokine-dependent growth of hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:1367–77. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K, Sha J, Harter ML. MyoD, a new function: ensuring “DNA licensing”. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1871–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K, Sha J, Harter ML. Activation of Cdc6 by MyoD is associated with the expansion of quiescent myogenic satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:39–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welch JJ, Watts JA, Vakoc CR, Yao Y, Wang H, Hardison RC, et al. Global regulation of erythroid gene expression by transcription factor GATA-1. Blood. 2004;104:3136–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szalai G, LaRue AC, Watson DK. Molecular mechanisms of megakaryopoiesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2460–76. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choe KS, Radparvar F, Matushansky I, Rekhtman N, Han X, Skoultchi AI. Reversal of tumorigenicity and the block to differentiation in erythroleukemia cells by GATA-1. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6363–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halevy O, Novitch BG, Spicer DB, Skapek SX, Rhee J, Hannon GJ, et al. Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science. 1995;267:1018–21. doi: 10.1126/science.7863327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin F, Fondell JD. A novel androgen receptor-binding element modulates Cdc6 transcription in prostate cancer cells during cell-cycle progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4826–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abad JL, Serrano F, San Román AL, Delgado R, Bernad A, González MA. Single-step, multiple retroviral transduction of human T cells. J Gene Med. 2002;4:27–37. doi: 10.1002/jgm.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naviaux RK, Costanzi E, Haas M, Verma IM. The pCL vector system: rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J Virol. 1996;70:5701–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5701-5705.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.