Abstract

Background

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) relieve irritability within days in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD); however, the effects on other affective symptoms in PMDD remain to be demonstrated.

Methods

We performed hourly ratings in women with PMDD to test the specificity of the therapeutic effects of SRIs and to determine whether the kinetics of these effects differ from those of the symptom offset accompanying menses. Twelve women with PMDD received fluoxetine (20 mg daily) during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Twelve other women with PMDD received no treatment. Outcome measures included a visual analogue scale completed hourly before and after either the start of SRIs or at menses-onset in the untreated women and the premenstrual tension syndrome (PMTS) scale completed daily. Data were analyzed by ANOVA-R.

Results

Hourly VAS scores significantly improved after SRI in irritability as well as sadness, anxiety, and mood swings. Compared with the symptomatic pretreatment baseline, PMTS scores significantly improved on the second day after the start of SRI (p < .01). An identical time course of symptom improvement occurred after both SRI and menses-onset.

Conclusion and Discussion

These data document that the rapid response to SRI was not limited to irritability. The similar kinetics in the remission of PMDD after SRIs and after menses-onset suggest both a phenotype reflecting the relative capacity to rapidly change affective state, and a possible therapeutic mechanism by which SRIs recruit this endogenous capacity to change state, normally expressed around menses-onset in women with PMDD.

Keywords: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, fluoxetine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, treatment response

INTRODUCTION

The relatively rapid symptom improvement after initiation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) in severe premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD; i.e. within days) has led to the successful use of symptom-onset treatment in women with PMDD.[1] A study by Landen et al.[2] documented the timing of the onset of therapeutic action of paroxetine in women with PMDD under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions. Compared with placebo, paroxetine significantly improved the symptom of irritability within 3 days after the start of treatment. These important observations not only guide clinical practice in this condition, but suggest that the mechanism of action of SRIs in PMDD differs from that presumed to underlie the therapeutic effects of SRIs in depression and anxiety disorders. Nonetheless, several characteristics of the rapid therapeutic response in PMDD remain to be addressed. First, in the study by Landen et al.,[2] although significant differences in symptom severity between SRI and placebo appeared after 3 days of treatment, the difference reflected a waning of the improvement in the placebo group observed during the first and second day of treatment. Indeed, the group data, notwithstanding, some women with PMDD appeared to respond to SRIs after the first day. Thus, some women with PMDD could experience improvement within hours of taking SRIs similar to the symptom response to the serotonergic agent m-CPP reported by Su et al.[3] Second, since the two hourly symptom ratings were not obtained beyond the first day of treatment, it is possible that a circadian change in symptom improvement (with possible morning worsening) was present after the first day that was not detectable by the evening-only ratings after the first day of treatment. Third, it remains to be demonstrated if the rapid therapeutic effect of SRIs in PMDD is confined to the symptom of irritability or whether other affective symptoms in this condition also remit rapidly with SRIs. In the Landen study,[2] women with PMDD were selected for the presence of prominent irritability, and only a composite score, which contained a range of both physical and affective symptoms was employed to monitor response in symptoms other than irritability. In particular, it would be important clinically to determine if symptoms of sadness and anxiety experienced by women with PMDD show a similar rapid response to SRIs as that observed for the symptom of irritability. Finally, it is possible that the kinetics of the “switch-out” (or rapid remission of symptoms) in PMDD, are similar to those observed at the onset of menses. A rapid remission of symptoms in PMDD also is observed naturalistically proximate to the onset of menses and the luteal to follicular phase transition. Previous reports by Bancroft[4] describe substantial individual variability in the rapidity of symptom remission at menses-onset in women with PMDD. Similar variability in the response to SRIs also is suggested by Landen et al.,[2] since some women appeared to respond rapidly within the first two days of treatment, whereas the group as a whole did not meet criteria for response until after the third day of treatment. Similar kinetics between the remission of symptoms in PMDD after SRIs and after the onset of menses could suggest the following: (1) the presence of a phenotype reflecting the relative capacity to rapidly change affective state; and (2) a possible therapeutic mechanism by which SRIs activate or “recruit” this endogenous capacity to change state, normally expressed around the onset of menses.

In this study, we address these questions and document the pattern of acute symptom response, including irritability, depression, anxiety, and mood swings, to the SRI fluoxetine in symptomatic women with PMDD during the luteal phase. First, we employ symptom self-ratings completed on an hourly basis each day over several days of treatment to monitor kinetics of symptom change in PMDD that precedes the final clinical response to fluoxetine. Second, we compare the response to fluoxetine of the four core symptoms of PMDD listed above. Finally, we investigate whether the kinetics of the SRI-induced switch-out differ from those accompanying menses under nonpharmacological conditions.

METHODS

SUBJECT SELECTION

We studied 24 women with PMDD admitted to the NIMH Out-patient clinic, 12 received treatment with fluoxetine and 12 received no treatment. All women were healthy and reported regular menstrual cycles (i.e. 21–35 days). Prospective participants were screened with a daily visual analogue scale of self-ratings of affective symptoms (i.e. a 100 mm line bracketed by severity extremes [none to worst ever] for sadness, irritability, anxiety, and mood swings).[5] In at least two of three menstrual cycles, women diagnosed with PMDD showed at least a 30% higher mean level of sadness, irritability, anxiety, or mood swings in the week before menses compared with the week after the end of menses. (Ratings were adjusted for the range of the scale employed by dividing 30% by the percent of the scale spanned by the extreme high and low ratings.) This criterion operationalizes both the DSM-IV severity and cyclicity criteria for PMDD.[6] Thus, all women met the criteria for PMDD of the DSM-IV.[7] All participants were given a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID),[7] women with PMDD were required to have no current or recent (<2 years) Axis I condition.

Written informed consent was obtained from each subject for completion of the symptom ratings and collection of the blood samples. As a part of this protocol, women consented to receive standard therapy with an SRI.

PROCEDURE

Twelve women with PMDD participated in an open label treatment in which we evaluated the time course of symptom response after commencing treatment with a 20 mg daily dose of fluoxetine. Symptom ratings to monitor the daily and hourly change in symptom severity included the following scales: (1) The Rating Scale for Premenstrual Tension Syndrome (PMTS), both self and observer (PMTS-Rater) forms, were completed by only those women with PMDD receiving fluoxetine.[8] The PMTS-Rater was administered only on Days 1, 2, and 3 to clinically confirm the presence of symptoms by telephone, whereas, PMTS ratings were completed daily until after the onset of menses. (2) The Hourly Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was completed by all women with PMDD regardless of treatment group. Participants were asked to indicate on a 100-mm line the severity of four symptoms commonly associated with PMDD: anxiety, irritability, sadness, and mood instability. Women rated themselves on all four symptoms every hour.

The twelve women who were given fluoxetine determined the onset of the LH surge by a home urinary assay kit, and then monitored the onset of their typical PMDD symptoms with the Daily Rating Form (DRF).[9] The DRF is a five point Likert-type scale that measures the severity of common symptoms of PMDD such as sadness, anxiety, irritability, cravings for food, impaired function, bloating, and breast pain. Scores range from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extreme). Patients were instructed to complete this form each evening based on how they felt during the previous 12 hr. After the LH surge, women called the clinic on the first day that they rated a DRF mood symptom severity at two or greater (i.e. minimal symptom severity). The next morning (Day 1), participants completed the PMTS[8] rating scale. Additionally, on Day 1 all participants were instructed to complete the hourly VAS ratings upon wakening and continue ratings until bedtime. After 2 days of symptoms, each woman started fluoxetine at a dose of 20 mg per day. Participants were instructed to continue ratings until 2 days after the onset of menses. During the early follicular phase of the next menstrual cycle, blood samples were obtained for measurement of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine plasma levels.

As a comparison group, twelve women with PMDD who did not receive any treatment completed identical hourly VAS ratings prior to and after menses to permit evaluation of the time course of symptom change in response to menses (i.e. menses-related switch out of symptoms). These women who did not receive treatment were asked to complete the hourly VAS in a similar manner as those receiving treatment except starting 10 days after a positive LH surge test and continuing until symptoms had ceased for 3 days.

Side effects experienced by the women receiving an SRI were monitored by clinical assessment only.

DATA ANALYSIS

Treatment response to fluoxetine: to examine the kinetics of the response to SRIs in the hourly VAS, analysis of variance with repeated measures (ANOVA-Rs) were performed with VAS symptoms (i.e. irritability, anxiety, depression, and mood instability), day of treatment (1–5), and hour (1–10) as the within group variables. Hour 1 was the first rating at the beginning of the day. We included the ratings for the next 10 hr since the number of hours rated in the evening varied among the women depending on their bedtimes. To avoid violations of sphericity requirements, Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were used for all P-values in the ANOVA-Rs.

In each woman, the time taken to achieve a clinical response was defined by the number of days from the start of fluoxetine treatment until a 50% reduction in PMTS rating scores was achieved compared with the symptomatic baseline. Additionally, the daily PMTS rating scores were compared by ANOVA-Rs with time as the within group variable (i.e. days 1 through 5 of treatment). The number of days of ratings that each woman rated varied depending on when menses started; since all but one woman experienced a 50% or greater response within 5 days after starting fluoxetine, we analyzed only the first 5 days of treatment in the ANOVA-R. When indicated by significant ANOVA-R, post hoc Bonferroni t tests were performed to identify the first day posttreatment on which there was a significant difference in symptom scores compared with pretreatment baseline. A remission of symptoms was defined by PMTS scores 5 for three consecutive days,[10] whereas a partial response was defined by PMTS scores that were ≤50% lower than baseline but did not meet criteria for remission. Plasma levels of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine were compared by Students t test between those women who met criteria for remission and those who were partial responders.

Finally, we compared the hourly VAS symptom ratings after fluoxetine treatment with those after the onset of menses in untreated women by ANOVA-R with treatment group (fluoxetine treatment versus no treatment [i.e. onset of menses]), and symptom (anxiety, irritability, depression, and mood swings), day (1–3), and hour (1–10) as the within subjects variables. Day 1 was either the first day of fluoxetine treatment or the first day of menses in the untreated women. We also compared prestudy baseline symptom severity ratings on the VAS and demographic variables between the treated and untreated groups by ANOVA-R and Students t test, respectively.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the two groups of women are listed in Table 1. The women in the SRI treatment group were similar in age and in the numbers of women with a past history of depression to those in the untreated group (Table 1). The two groups also did not differ in baseline severity scores for the symptoms of irritability, anxiety, sadness, and mood swings. One of the women who was treated with fluoxetine completed only 2 days of ratings. Additionally, five women in the untreated group stopped their ratings before the third day postmenses. Nonetheless, since all women reported a substantial improvement in their ratings during the constricted time period (i.e. the ratings captured the switch-out), we included their ratings in the respective analyses. SRI was well tolerated by the women in this trial and none of the women in either the treated or untreated group reported the emergence of suicidal ideation during the study.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of women with PMDD who were treated with SRI (n = 12) and those who received no treatment (n = 12)

| SRI treatment | No treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD)a | 36 (6.2) | 38 (6.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 6 (50.0) | 9 (75.0) | |

| African American | 4 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Asian | 1 (8.3) | 0 | |

| Number of women with children | 8 | 6 | |

| Past diagnosis, no. (%) | |||

| Major depression | 4 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Minor depression | 1 (8.3) | 0 | |

| No. Axis I disorder | 7 (58.3) | 9 (75.0) | |

| Principle symptom, no. (%) | |||

| Irritability | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Depression | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Anxiety | 0 (0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Unstable mood | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Previous SRI use, no. (%)a | 4 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Baseline PMTS score, mean (SD) | 22 (5.2) | ||

| Fluoxetine level (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 53.8 (16.4) | ||

| Norfluoxetine level (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 61.1(20.7) | ||

| Baseline VAS symptom scores (average of 2 baseline menstrual cycles)b | |||

| Irritability | Premenses mean (SD) | 41.3 (14.7) | 30.1 (15.3) |

| Postmenses mean (SD) | 85.4 (14.7) | 83.5 (11.4) | |

| Anxiety | Premenses mean (SD) | 40.6 (13.9) | 35.3 (17.2) |

| Postmenses mean (SD) | 85.1 (13.8) | 83.2 (10.3) | |

| Sadness | Premenses mean (SD) | 51.1 (10.2) | 41.4 (13.5) |

| Postmenses mean (SD) | 86.0 (12.7) | 82.0 (9.4) | |

| Mood swings | Premenses mean (SD) | 40.5 (11.0) | 41.4 (13.5) |

| Postmenses mean (SD) | 86.0 (13.0) | 83.3 (9.4) | |

In women with PMDD who received treatment, serum samples obtained during the follicular phase were assayed for fluoxetine and norfluoxetine by HPLC (Mayo Laboratories, Rochester, MN). Inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were as follows: fluoxetine–−7.7 and 6.6%, respectively; norfluoxetine–−8.0 and 4.9%, respectively.[33]

There were no differences in age between those women who received SRI and those who received no treatment (t22 = 0.7, P = NS). None of the women received SRIs within 2 years of entering this study; range = 3–13 years prior to study entry.

Baseline symptom severity scores did not differ between women who received SRI and those who were untreated. ANOVA-R showed no significant effects of group (Gp) or group by menstrual cycle phase (Gp × phase) for any of the four symptoms measured (P = NS for all comparisons): Irritability group F1,22 = 2.6, Gp × phase F1,22 = 1.3. Anxiety group F1,22 = 0.8, Gp × phase F1,22 = 0.2. Sadness group F1,22 = 3.0 Gp × phase F1,22 = 0.6. Mood swings group F1,22 = 1.6, Gp × phase F1,22 = 0.2.

TIME COURSE OF SYMPTOM RESPONSE AFTER SRI

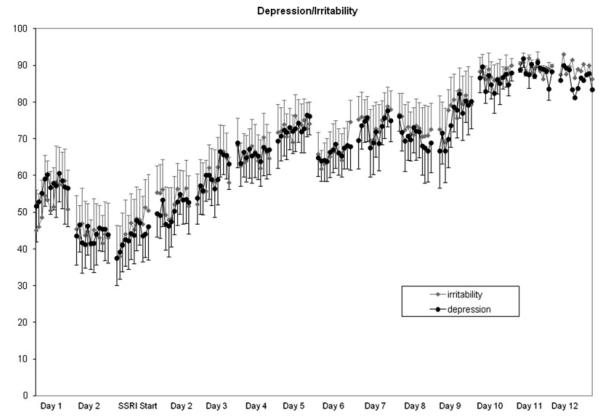

All of the hourly VAS symptoms showed a similar significant improvement after the start of treatment (i.e. main effect of day F5,50 = 5.9, P = .002), which did not differ across individual symptoms (Fig. 2.) There also was a significant main effect of hour, which reflected an improvement in symptom severity from the first to the last rating of the day regardless of symptom or day of treatment (ANOVA-R: main effect of time F9,90 = 3.1, P = .04; no significant interaction effects P [range] = .3–.5). A similar pattern of diurnal symptom improvement also was observed in the untreated women with PMDD after the onset of menses.

Figure 2.

Hourly VAS ratings of sadness and irritability for 10 hr each day prior to and after the start of treatment with fluoxetine 20 mg daily on the morning of Day 1 (mean + SEM). Ratings on the VAS scales showed a significant improvement after SRI in the symptoms of irritability, as well as anxiety, sadness, and mood swings after the start of treatment that did not differ across individual symptoms. (ANOVA-R: main effect of symptom type F3,30 = 0.9, P = NS, symptom × day interaction F15,150 = 1.8, P = .2), symptom × day ×hour interaction F135,1350 = 1.0, P = .5). There also was significant improvement in the symptom severity from the first to the last ratings of the day regardless of symptom or day of treatment.

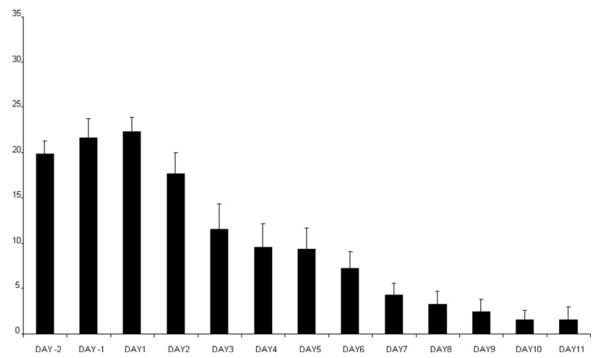

Relative to their baseline, pretreatment scores, women experienced a 50% reduction in PMTS rating scores within 1 to 6 days after initiating fluoxetine (median = 2 days; mean ± SD = 2.9 ± 1.6 days). experienced full Seven women remission and five women were partial responders. Seven women experienced a 50% reduction relative to baseline within 2 days of treatment (four of whom experienced full remission), one woman after 3 days of treatment, two women after 4 days, and one each after 5 and 6 days of treatment. ANOVA-R of the PMTS ratings between Day 1 and Day 5 of treatment showed a significant effect of day (ANOVA-R: F4,40 = 9.1, P < .001). Post hoc Bonferroni t tests showed that relative to baseline prior to treatment, there was a significant improvement on the second day after the start of treatment, which was maintained during the subsequent days until menses (Bonferroni t = 3.8, df = 40, P < .01) with four comparisons (Fig. 1). The effect size of the difference between PMTS scores at baseline and after day 5 of SRI treatment was 0.7.

Figure 1.

Scores on the rating scale for PMTS (mean + SEM) were significantly improved compared with baseline on the second day after the start of SRI treatment (Day 1). Improvement was maintained until menses (ANOVA-R: F4,40 = 9.1, P = .001; Bonferroni t ≤ 3.8, df = 40, P ≤ .01). Seven of 12 women experienced a 50% reduction relative to baseline within 2 days of treatment.

There were no significant differences in plasma levels of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine in the women who met criteria for remission compared with those who met criteria for a partial therapeutic response (t10 = 0.03 and 0.4; respectively; P = NS)

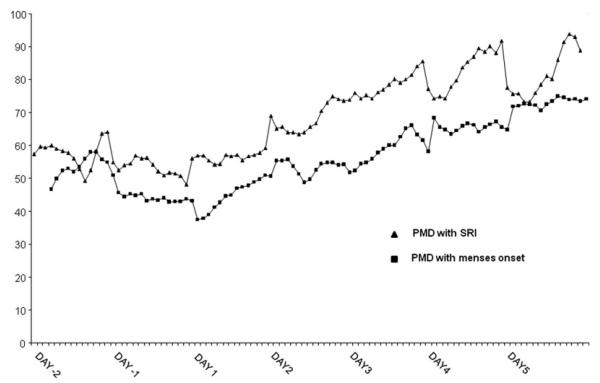

SYMPTOM RESPONSES TO SRI AND THE ONSET OF MENSES (Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Three-point moving averages of the hourly VAS rating of irritability in women with PMDD who were treated with fluoxetine during the luteal phase, and women with PMDD who received no treatment. Ratings in women receiving fluoxetine represent pretreatment ratings (Day −2, −1) and after receiving fluoxetine 20 mg daily in morning on Day 1, whereas ratings in untreated women represent ratings premenses (Day −2, −1) and after the onset of menses (Day 1). The onset of menses and the initiation of SRI treatment were accompanied by similar patterns of symptom response (ANOVA-R of the ratings for all four symptoms during Day 1–3 demonstrated an identical pattern of symptom improvement with significant effects of both day and hour that reflected an improvement in scores of all four symptoms after the onset of either SRI treatment or menses (main effect of day F2,32 = 8.3, P = .003; main effect of hour F9,144 = 5.9, P < .001).

We observed an identical pattern of symptom improvement in the VAS scores after both SRI treatment and menses onset. No significant main or interaction effects of group (i.e. treatment versus onset of menses) were observed in the pattern of symptom response. The onset of menses and the initiation of SRI treatment were accompanied by an identical pattern of responses with significant effects of both day and hour that reflected an improvement in scores after the onset of either treatment or menses (main effect of day F2,32 = 8.3, P = .003; main effect of hour F9,144 = 5.9, P < .001). However, there were no significant main or interaction effects of group (i.e. SRI versus menses; main effect of group F1,16 = 2.3, P = NS) with the exception of a trend for a significant symptom × day × group interaction (F6,96 = 3.2, P = .05), which reflected a relatively blunted improvement in the symptom of mood instability in the unmedicated women whose symptom ratings were monitored around menses compared with those receiving SRI. Finally, there were no significant interaction effects between group and hour (F9,117 = 1.1, P = NS).

DISCUSSION

These data document the hourly change in PMDD symptoms over several days after treatment with an SRI. Symptoms improved within 48 hr after starting treatment. We also noted a significant effect of time of day (independent of the day of treatment) suggesting that symptoms improved over the day. Additionally, the rapid response was observed in all four symptoms measured and, therefore, was not limited to the symptom of irritability. Finally, we observed an identical temporal pattern of symptom remission after the initiation of SRI treatment as that observed after the onset of menses.

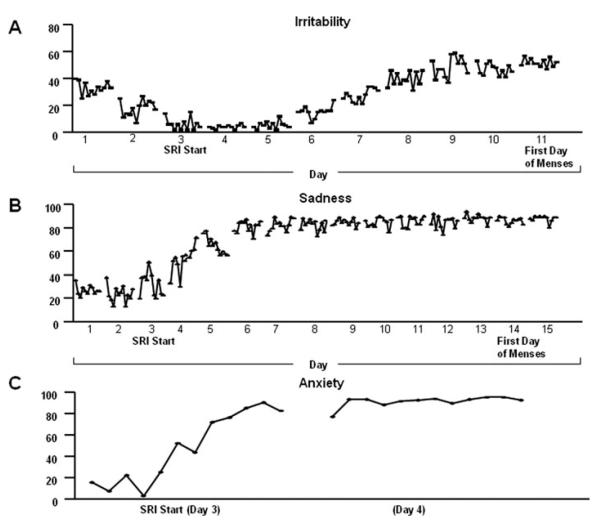

Our data chronicle the hourly changes in mood symptoms after treatment with fluoxetine in women with PMDD. Although the majority of women responded 48 hr after starting fluoxetine, the time taken to achieve clinical response ranged from 1 to 6 days (Fig. 4). Notwithstanding the range of times to meet response criteria, all women responded in a much shorter time than would be predicted from studies of SRIs in the treatment of depressive or anxiety disorders. In a previous placebo-controlled trial, a rapid improvement in the symptom of irritability after 20 mg of paroxetine was demonstrated in 22 women with PMDD,[2] and by the end of the third day of treatment, women were more likely to meet criteria for clinical response and the average VAS irritability scores were significantly lower on active drug compared with placebo. Although not placebo-controlled, our data are consistent with these findings as well as those from Kornstein et al.[1] who reported the efficacy of symptom-onset treatment with low-dose sertraline in women with PMDD under placebo-controlled conditions. We observed a significant improvement from baseline scores on the PMTS ratings on the morning of Day 3 of treatment (i.e. 48 hr after treatment started); however, both our data and those of Landen[2] show individual differences in the time taken to achieve clinical response to SRI treatment.

Figure 4.

Examples of symptom remission (i.e. switch-out) characteristics after SRI treatment in three separate patients: (1) a gradual remission of symptoms over 5 to 6 days, (2) moderately rapid symptom remission over 2 to 3 days, and (3) a switch-out of the symptomatic state within 24 hr.

The rapidity of improvement after ingesting fluoxetine parallels observations of an acute improvement in PMDD within hours after either oral m-CPP[3] or fenfluramine[11] administration. The acute remission of symptoms after either m-CPP or fenfluramine, however, was not maintained, and, therefore, a sustained therapeutic effect may require several days of repeated administration of the drug, consistent with reports of the absence of therapeutic benefits after a single high dose of fluoxetine administered during the luteal phase in PMDD.[12]

In the study by Landen et al.,[2] the authors suggest that the rapid therapeutic effects of SRIs in PMDD are most robustly demonstrated in the symptom of irritability. However, we observed rapid and significant improvements in the VAS scores of anxiety, sadness, and mood swings as well as irritability. The women with PMDD in the Landen study were selected on the basis of the prominence of irritability in their clinical presentation and self ratings,[2] whereas the women in our study could meet PMDD criteria in any one of the four affective symptoms measured in the study.

In addition to improvements in all four symptoms over each day of treatment, we also observed an effect of the hour at which ratings were completed during the day, with an improvement in all VAS symptom ratings from morning to night during each day of therapy. Upon review of the averages of the hourly VAS ratings, we observed with few exceptions that on each day of treatment the worse scores (i.e. lowest) and best scores were in the first and second halves of the day, respectively. However, this difference in the earlier versus the later ratings was present on the first day of treatment, did not differ as a function of the duration of treatment, and was similar to the pattern of change in symptom severity observed in the untreated comparison group. A similar phenomenon was observed in the study by Landen et al.[2] on the first day after the administration of paroxetine.

A rapid symptom response, similar to that seen post-SRI, also was observed during the 3 days after mensesonset in a separate group of untreated women with PMDD. The acute improvement occurred in all four symptoms measured, with no difference between treated and untreated women in the hourly or daily change in symptoms during the 3 days evaluated. These similarities in response might simply reflect a generic “switch-out” from the symptomatic state in women with PMDD in response to either successful SRI treatment or menses (or the luteal-follicular transition). Additionally, we observed considerable interindividual variation in the rapidity of the switch-out after both SRIs and menses. Thus, the kinetics of the switch-out in PMDD could reflect a phenotype reflecting how quickly a woman’s affective state can change in response to a perturbation; SRIs could recruit this capacity to change affective state and advance the switch-out that normally occurs after menses-onset. Finally, the switch-out related to either SRI treatment or the onset of menses could reflect a shared biology in a process fundamental to symptom relief in these women with PMDD. In a previous study,[13] we demonstrated that terminating the luteal phase and inducing menses with the progesterone receptor antagonist RU-486 had no effect on symptoms in PMDD. Indeed, to the contrary, symptoms proceeded as they would have occurred had normal luteal function been preserved. Thus, symptom remission in women with PMDD does not appear to simply depend on the termination of corpus luteum function, declining estradiol and progesterone levels, or the onset of menses. The characteristic symptom remission in PMDD within a few days after the onset of menses, therefore, must involve some as yet identified biological process that would mimic the mechanism of action of SRIs in PMDD. One possibility is that both SRIs and events surrounding menses (and the end of the luteal phase) increase central serotonergic system function. Indeed, Landen et al.[2], suggest that an acute increase in serotonin is sufficient to improve symptoms in PMDD, whereas a more prolonged incremental process involving 5HT1A autoreceptor down regulation, serotonin transporter protein inhibition, and alterations in neuronal plasticity underlies the therapeutic effects of SRIs in depression. Alternately, Pinna et al.[14] argue that the rapid therapeutic effects of low-dose SRIs is mediated through increased CNS neurosteroid synthesis (and presumed increased GABAA receptor function) and not by an increase in serotonergic system function. The actions of both SRIs and menses to induce a remission of PMDD symptoms, then, could be mediated by increased GABA activity. The serotonin system—in particular, the 5-HT1A receptor—and GABAergic activity share reciprocal relationships, with reductions in serotonin receptor function associated with increased GABA activity in the amygdala.[15–18] Thus, an acute increase in GABA function, secondary to increased neurosteroid production, could rapidly down regulate 5-HT1A receptor function, and be the more proximate mechanism responsible for the therapeutic action of SRIs in PMDD. Ambiguity about the mechanism of action notwithstanding, the striking similarity of the kinetics observed between SRIs and menses suggests that elucidation of underpinnings of the therapeutic response to SRIs in PMDD may shed light on a naturally occurring affective switch, the menses.

Although this study clearly demonstrates the rapid response of core PMDD symptoms to SRIs on both a daily and hourly basis, it has several limitations. First, it is not placebo controlled and, therefore, we cannot distinguish the component of the observed therapeutic response mediated by the nonspecific effects of medication administration. Numerous placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated the effects of SRIs in this condition,[1,19–32] and it was not the intention of this study to demonstrate the superior efficacy of SRIs compared with placebo. Nonetheless, these data legitimately portray the open-label clinical use of these medications in PMDD, and a similar time course also was observed by Landen et al.[2] under placebo-controlled conditions. As a caveat, however, the rapidity of the symptom response to SRIs in PMDD should not be generalized to either women with a premenstrual exacerbation of an Axis 1 psychiatric condition or those women with PMDD with a comorbid depressive illness. Second, the results are derived from a small sample size, and the different timing of the onsets of symptoms during the luteal phase and during menses led to variation in the numbers of days of ratings completed by each woman. Finally, confidence would be increased in our observations of a “diurnal-like” improvement in the hourly symptom ratings after the start of fluoxetine had we obtained hourly ratings for more days prior to treatment. This was not possible since women started treatment several days after symptoms arose; however, a comparison group of untreated or placebo treated women who rated during the same time intervals could serve to address this question.

In summary, these data demonstrate the rapid symptom improvement in women with PMDD, consistent with placebo-controlled studies of symptom-onset SRI treatment of PMDD.[1] The important contribution of these data is the elucidation and confirmation of the time course of the symptom response, which commences on the first day of treatment, progresses each day with peak responsivity 48 hr after treatment, and is maintained thereafter until the onset of menses. The mechanism underlying the rapid effects of SRIs in PMDD remains to be determined; however, these data suggest that it is not solely secondary to an acute improvement in irritability. The similarities between the symptomatic response to initiation of an SRI and to the onset of menses in untreated symptomatic women suggest that a shared mechanism may lead to the switch-out from the symptomatic state in women with PMDD. Enhanced neurosteroid activity possibly may mediate this switch-out, an hypothesis that could be tested by using specific inhibitors of neurosteroid synthetic enzymes to attempt to reverse the effects of fluoxetine in women with PMDD. Finally, it remains to be determined whether the latencies to response to SRIs identify meaningful phenotypic differences in PMDD.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms. Merry Danaceau for their clinical support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program, Bethesda Maryland.

This work was written as part of Dr. Schmidt’s official duties as a Government employee. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, NIH, HHS, or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kornstein SG, Pearlstein TB, Fayyad R, et al. Low-dose sertraline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe premenstrual syndrome: efficacy of 3 dosing strategies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1624–1632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landen M, Erlandsson H, Bengtsson F, et al. Short onset of action of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor when used to reduce premenstrual irritability. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:585–592. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su T-P, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, et al. Effect of menstrual cycle phase on neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to the serotonin agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine in women with premenstrual syndrome and controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1220–1228. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.4.3905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft J. The premenstrual syndrome - a reappraisal of the concept and the evidence. Psychol Med. 1993;(Suppl 24):1–47. doi: 10.1017/s0264180100001272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubinow DR, Roy-Byrne PP, Hoban MC, et al. Prospective assessment of menstrually related mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:684–686. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith MJ, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Operationalizing DSM-IV criteria for PMDD: selecting symptomatic and asymptomatic cycles for research. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner M, Haskett RF, Carroll BJ. Premenstrual tension syndrome: the development of research diagnostic criteria and new rating scales. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1980;62:177–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endicott J, Harrison W. Daily Rating of Severity of Problems Form. New York State Psychiatric Institute, Department of Research Assessment and Training; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haskett RF, Abplanalp JM. Premenstrual tension syndrome: diagnostic criteria and selection of research subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1983;9:125–138. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(83)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brzezinski AA, Wurtman JJ, Wurtman RJ, et al. d-Fenfluramine suppresses the increased calorie and carbohydrate intakes and improves the mood of women with premenstrual depression. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miner C, Brown E, McCray S, et al. Weekly luteal-phase dosing with enteric-coated fluoxetine 90 mg in premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Ther. 2002;24:417–433. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)85043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Grover GN, et al. Lack of effect of induced menses on symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1174–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J-J, Hahm E-T, Lee C-H, et al. Serotonergic modulation of GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in mechanically isolated rat medial preoptic area neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:340–352. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibille E, Pavlides C, Benke D, et al. Genetic inactivation of the serotonin1A receptor in mice results in downregulation of major GABAA receptor α subunits, reduction of GABAA receptor binding and benzodiazepine-resistant anxiety. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2758–2765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02758.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heine PA, Taylor JA, Iwamoto GA, et al. Increased adipose tissue in male and female estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12729–12734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robichaud M, Debonnel G. Modulation of the firing activity of female dorsal raphe nucleus serotonergic neurons by neuroactive steroids. J Endocrinol. 2004;182:11–21. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimmock PW, Wyatt KM, Jones PW, et al. Efficacy of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in premenstrual syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet. 2000;356:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonkers KA, Halbreich U, Freeman E, et al. Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;278:983–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown J, O’Brien PMS, Marjoribanks J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome (review) Cochrane Libr. 2009;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub2. CD001396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah NR, Jones JB, Aperi J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1175–1182. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816fd73b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner M, Steinberg S, Stewart D, et al. Fluoxetine in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1529–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506083322301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundblad S, Modigh K, Andersch B, et al. Clomipramine effectively reduces premenstrual irritability and dysphoria: a placebo-controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbreich U, Smoller JW. Intermittent luteal phase sertraline treatment of dysphoric premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:399–402. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundblad C, Hedberg MA, Eriksson E. Clomipramine administered during the luteal phase reduces the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:133–145. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Continuous or intermittent dosing with sertraline for patients with severe premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:343–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eriksson E, Ekman A, Sinclair S, et al. Escitalopram administered in the luteal phase exerts a marked and dose-dependent effect in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:195–202. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181678a28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landen M, Nissbrandt H, Allgulander C, et al. Placebo-controlled trial comparing intermittent and continuous paroxetine in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:153–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wikander K, Sundblad C, Andersch B, et al. Citalopram in premenstrual dysphoria: is intermittent treatment during luteal phases more effective than continuous medication throughout the menstrual cycle? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:390–398. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jermain DM, Preece CK, Sykes RL, et al. Luteal phase sertraline treatment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:328–332. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yonkers KA, Holthausen GA, Poschman K, et al. Symptom-onset treatment for women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:198–202. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000203197.03829.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nichols JH, Charlson JR, Lawson GM. Automated HPLC assay of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine in serum. Clin Chem. 1994;40:1312–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]