Abstract

The balance between cell survival and cell death is critical for normal lymphoid development. This balance is maintained by signals through lymphocyte antigen receptors and death receptors such as CD95/Fas. In some cells, ligating the B cell antigen receptor can protect the cell from apoptosis induced by CD95. Here we report that ligation of CD95 inhibits antigen receptor-mediated signaling. Pretreating CD40-stimulated tonsillar B cells with anti-CD95 abolished B cell antigen receptor-mediated calcium mobilization. Furthermore, CD95 ligation led to the caspase-dependent inhibition of antigen receptor-induced calcium mobilization and to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in B and T cell lines. A target of CD95-mediated caspase 3-like activity early in the apoptotic process is the adaptor protein GrpL/Gads. GrpL constitutively interacts with SLP-76 via its C-terminal SH3 domain to regulate transcription factors such as NF-AT. Cleavage of GrpL removes the C-terminal SH3 domain so that it is no longer capable of recruiting SLP-76 to the membrane. Transfection of a truncated form of GrpL into Jurkat T cells blocked T cell antigen receptor-induced activation of NF-AT. These results suggest that CD95 signaling can desensitize antigen receptors, in part via cleavage of the GrpL adaptor.

CD95 (Fas)-induced apoptosis is a critical component of normal tissue development and homeostasis. Mice with nonfunctional CD95 or CD95 ligands display characteristics of lymphoproliferative disorder such as lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and elevated secretion of IgM and IgG (reviewed in ref. 1). These mice also secrete anti-DNA autoantibodies and rheumatoid factor.

CD95 engagement triggers a series of events that lead to the commitment to cell death (reviewed in ref. 2). This commitment stage requires key death-inducing enzymes called caspases. Caspases act, in part, by cleaving proteins that are essential for cell survival and proliferation. Substrates for caspases include molecules involved in DNA repair mechanisms such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and DNA-dependent protein kinase and proteins involved in the structural integrity of the cell such as nuclear lamin and gelsolin. Other targets for caspase activity are proteins involved in signal transduction pathways.

In addition to CD95, other receptor systems also contribute to the regulation of cell fate. In particular, signals from CD95 and lymphocyte antigen receptors integrate to dictate the outcome of cell stimulation. For example, antigen receptor stimulation before CD95 ligation protects cells from CD95-mediated death and may even induce the cells to proliferate (3, 4). In some instances, CD95 ligation may precede antigen receptor cross-linking. We investigated how CD95-mediated events affect antigen receptor-induced signal transduction.

In this report, we show that CD95-induced caspase activation before antigen receptor stimulation disables antigen receptor signaling. As part of the mechanism for this inhibition, caspases cleave the GrpL (Gads/Mona) adaptor protein. This Grb2 family member contains an N-terminal SH3 domain, an SH2 domain, a proline/glutamine-rich unique region, and a C-terminal SH3 domain (5–7). In T cells, GrpL constitutively binds SLP-76 via its C-terminal SH3 domain and inducibly binds LAT via its SH2 domain (5, 8–10). Thus, GrpL plays a key role in calcium mobilization and in the activation of the transcription factor NF-AT. Here we show that CD95 ligation leads to the cleavage of GrpL so that it cannot bind SLP-76. The truncated form of GrpL inhibits antigen receptor-mediated NF-AT signaling.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Antibodies.

The human B cell lines MP-1 and BJAB and the human T cell line Jurkat E6.1 were grown in RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% FCS, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, penicillin, streptomycin, and glutamine. Dense tonsillar B cells were prepared as described previously (11). The CD95 mAb IPO-4 was kindly provided by Svetlana Sidorenko (12). The GrpL and Mst1 antisera were prepared as described previously (5, 13). Active caspase 3 and Grb2 antisera were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). Polyclonal antisera specific for the phosphorylated forms of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-SLP-76 serum was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. G19–4 and 64.1 CD3 mAb were prepared in our laboratory.

Preparation of the GrpL mAb.

A mAb specific for GrpL was prepared by using the NS-1 fusion partner and spleen cells from BALB/c mice immunized with a glutathione S-transferase fusion protein expressing GrpL. One clone (4C6) produced an IgG2a mAb specific for GrpL but not for Bam32 protein or glutathione S-transferase controls (K.E.D. and E.A.C., unpublished data). We have designated the mAb UW40.

Reagents.

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), ionomycin, thapsigargin, and indo-1 were purchased from Calbiochem. FITC-conjugated Annexin V was purchased from CLONTECH. The peptide caspase inhibitors z-VAD-fmk, z-IETD-fmk, z-DEVD-fmk, and z-VDVAD-fmk (z, benzyloxycaronyl; fmk, fluoromethyl ketone) were purchased from Enzyme System Products (Livermore, CA). 35S-labeled methionine was obtained from NEN. The TNT Reticulocyte Lysate Transcription and Translation System was purchased from Promega. Recombinant, purified caspases were purchased from the Kamiya Biomedical Company (Seattle, WA).

Plasmid Constructs.

cDNA expressing myc-tagged, wild-type GrpL in the pcDNA3.1(+)Myc-His A vector (Invitrogen) was prepared as described previously (5). This construct was then subcloned into the pEF expression vector (kindly provided by G. Koretzky, Univ. of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) as described previously (5). The NF-AT luciferase reporter construct was also kindly provided by G. Koretzky. Mutagenesis of wild-type GrpL to generate D241E-GrpL and Δ241-GrpL was performed by using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene).

Protein Cleavage Experiments.

Cells were stimulated with anti-CD95 for the indicated periods of time, collected by centrifugation, and lysed in Triton lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4/150 mM NaCl/1% Triton X-100/5 mM EDTA/2 mM Na2VO4 and 25 μg/ml each leupeptin and aprotinin). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. In some experiments, protein was immunoprecipitated with the indicated antiserum or with mAb. The resulting proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blotted. In other experiments BJAB B cells were transiently transfected (250 V, 960 μF) by using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad).

In Vitro GrpL Transcription, Translation, and Cleavage.

Wild-type GrpL and a mutated D241E-GrpL were translated in vitro by using a coupled transcription and translation system with T7 RNA polymerase. Recombinant caspases were diluted in 5 μl of caspase buffer (100 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/10% sucrose/0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate/10 mM DTT/0.1 mg/ml ovalbumin) and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 1 μl of 35S-labeled, in vitro-translated GrpL. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 4× Laemmli sample buffer and subjected to SDS/PAGE before drying and autoradiography.

Calcium Assays.

Cells were incubated with CD95 mAb and loaded with indo-1 at 37°C. In some experiments, the cells were incubated with z-VAD-fmk before CD95 mAb stimulation. Calcium influx was measured by flow cytometry on a BD LSR system (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Intracellular calcium concentration was calculated as previously described (14, 15).

MAPK, SAPK/JNK, and p38 MAPK Activity.

Cells were treated with CD95 mAb (1 μg/ml) for 90 min before stimulation with the indicated combinations of either 1 μM ionomycin, 50 ng/ml PMA, or 20 μg/ml G19–4 anti-CD3 unless otherwise indicated. After either 5 min (for p42/44 MAPK) or 15 min (for JNK/SAPK and p38 MAPK) of stimulation, cells were harvested and lysed (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4/2 mM EGTA/50 mM β-glycerophosphate; 1% Triton X-100/10% glycerol/1 mM DTT/1 mM PMSF/25 μg/ml leupeptin/25 μg/ml aprotinin/2 mM Na2VO4/10 mM NaF). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Cell extract (30 μg of protein per sample) was subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blotted with antisera specific for the phosphorylated, activated forms of p42/44 MAPK, JNK/SAPK, or p38 MAPK.

Luciferase Assays.

Jurkat cells were cotransfected in triplicate with NF-AT luciferase plasmid (20 μg) and either pEF empty vector, pEF wild-type GrpL, or pEF Δ241-GrpL (10 μg) and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then transferred to 96-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per 100 μl. Cells were stimulated with G19–4 anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml), medium control, or the combination PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (5 μM) for 6–8 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then lysed in 50 μl of reporter lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min at room temperature. Luciferase activity was assayed by adding 20 μl of luciferase substrate (Promega) to 50 μ l of lysate and immediately measuring with a GenProbe Leader 1 luminometer (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD). To control for transfection efficiency, medium and anti-CD3 stimulation was determined as a percentage of maximal PMA/ionomycin stimulation.

Results and Discussion

CD95 Ligation Desensitizes the Antigen Receptor.

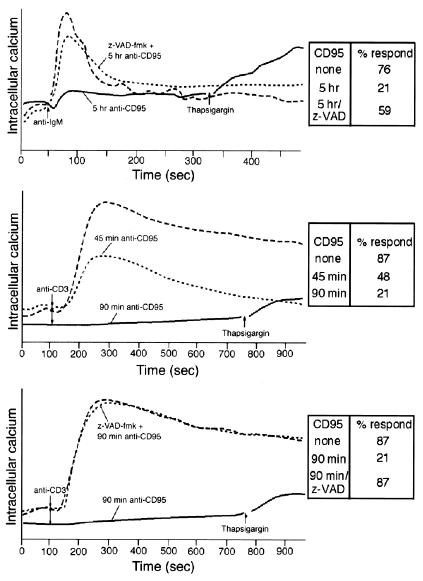

Resting tonsillar B cells were incubated with L cells expressing CD40 ligand (CD154+ L cells) to trigger the expression of CD95. Anti-CD95 staining revealed that >90% of the B cells were positive after a 90-hr incubation and that the mean expression was ≈20-fold greater than that of resting cells (data not shown). The activated cells were then incubated with CD95 mAb before B cell antigen receptor cross-linking (Fig. 1–Top). The calcium influx in cells not treated with CD95 mAb was 325 nM, compared with 218 nM in cells treated for 2 hr with CD95 mAb and 192 nM in cells treated for 5 hr with CD95 mAb. Although >85% of the cells were viable after 5 hr of CD95 mAb stimulation based on propidium iodide staining (data not shown), only about 21% of the cells had a detectable calcium response. Similar experiments were performed using the human Jurkat T cell line (Fig. 1 Middle). After 90 min of CD95 ligation, calcium mobilization was nearly abolished despite only 37% of cells being annexin V positive. Preincubation with z-VAD-fmk reversed this inhibition (Fig. 1 Bottom). These data are consistent with previously published experiments in T cell lines (16). Similar results were observed in the human MP-1 B cell line. Thus, CD95 ligation impairs subsequent antigen receptor signaling in both B and T cells at time points when the majority of cells are viable.

Figure 1.

CD95 ligation inhibits antigen receptor-mediated calcium mobilization. (Top) Dense tonsillar B cells (60–65% Percoll fraction) were plated on CD154+ L cells for 90–92 hr (8 × 107 B cells per 4 × 106 L cells) before CD95 stimulation (1 μg/ml) for 0 (long dashed line) or 5 (solid line) hr. Some cells were pretreated with z-VAD-fmk before CD95 ligation (short dashed line). The anti-IgM-induced (10 μg/ml) calcium response was measured by flow cytometry, and the data are reported as the ratio of calcium-bound indo-1 to free indo-1. Thapsigargin (7.5 μM) was added to the CD95 mAb-treated sample where indicated. (Middle) Indo-1-loaded Jurkat T cells were left untreated or pretreated with 100 ng/ml CD95 mAb for 0 (long-dashed line), 45 (short-dashed line), or 90 (solid line) min before TCR cross-linking. (Bottom) Indo-1-loaded Jurkat cells were treated with z-VAD-fmk (short-dashed line) or solvent control for 3 hr. Samples were then treated with CD95 mAb (short-dashed line and solid line) before anti-CD3 stimulation. Inset tables indicate the percent of cells responding.

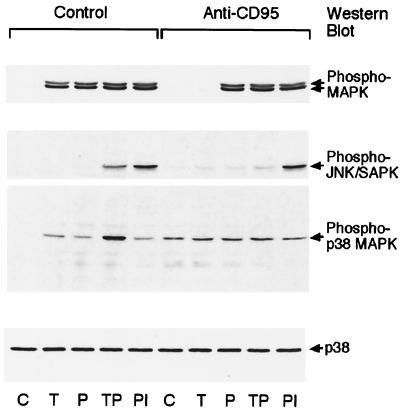

We then tested whether the CD95-mediated desensitization of antigen receptor signaling was limited to calcium mobilization. We analyzed signaling through the MAPK pathways, including p42/44 MAPK, JNK/SAPK, and p38 MAPK. CD95 ligation inhibited the T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-mediated activation of p42/44 MAPK, JNK/SAPK, and p38 MAPK (Fig. 2). However, PMA induced p42/44 MAPK activity, and the combination of PMA and ionomycin induced JNK/SAPK activity. CD95 ligation alone induced the activation of JNK/SAPK and p38 MAPK, consistent with previous reports (17, 18). The B cell antigen receptor-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein family kinases and Akt were also inhibited in MP-1 B cells pretreated with CD95 mAb (data not shown). These data indicate that antigen receptor-mediated activation of the MAPK pathways is selectively inhibited after CD95 cross-linking. However, pharmacological agents such as PMA and other receptors such as CD95 retain their ability to activate these signaling pathways.

Figure 2.

CD95 ligation inhibits antigen receptor-mediated MAPK activation. Jurkat T cells were left untreated or treated with CD95 mAb for 90 min before stimulation. The cells were then left unstimulated (C) or stimulated with anti-CD3 (T), PMA (P), anti-CD3 and PMA (TP), or PMA and ionomycin (PI). Lysates were Western blotted with phospho-specific antibodies against p42/44 MAPK (Top), JNK/SAPK (second from Top), or p38 MAPK (third from Top). As a loading control, lysates were Western blotted with antibodies against p38 MAPK (Bottom).

GrpL Is a Caspase Target.

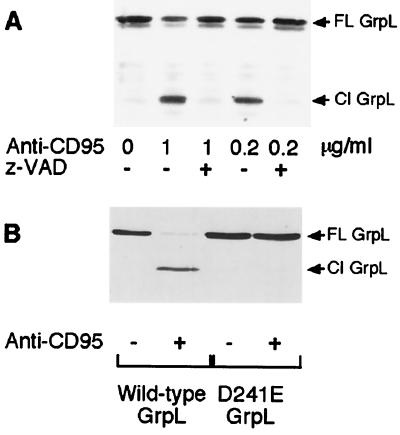

The above data indicate that CD95 ligation induces the desensitization of a variety of signaling pathways stemming from the antigen receptor in a caspase-dependent fashion. This observation suggests that caspases might target critical components of antigen receptor signaling pathways. Because GrpL is necessary for the recruitment of SLP-76 to LAT (19, 20) and thus is critical for calcium mobilization and NF-AT activation, we tested whether GrpL might be a caspase target. Western blotting analysis of MP-1 cells stimulated overnight with CD95 mAb revealed the presence of a lower molecular weight form of the protein (Fig. 3A). Preincubation with the general caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk prevented GrpL cleavage.

Figure 3.

GrpL is cleaved at Asp-241 in a caspase-dependent manner after CD95 ligation. (A) MP-1 B cells were treated with 50 μM z-VAD-fmk or DMSO solvent for 3 hr before incubation with the indicated amount of CD95 mAb for 18 hr. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GrpL mAb and Western blotted with GrpL antisera. (B) cDNA encoding either wild-type GrpL or D241E-GrpL was transfected into the GrpL-negative BJAB B cell line. After a 16-hr recovery period, the cells were incubated with 250 ng/ml CD95 mAb for 8 hr. Cell lysates were Western blotted with GrpL antisera. The arrows indicate full-length (FL) and cleaved (Cl) GrpL.

Examination of the GrpL sequence revealed a motif within the unique region, DIND 241G, that conformed to a consensus caspase cleavage site. To test whether this sequence within the unique region was the caspase cleavage site, we transfected GrpL-negative BJAB B cells with cDNA encoding either myc-tagged wild-type GrpL or a myc-tagged form of GrpL in which Asp-241 has been mutated to Glu (D241E-GrpL). Whereas wild-type GrpL was cleaved after CD95 ligation, D241E-GrpL was resistant to proteolysis (Fig. 3B). Thus, GrpL is cleaved by caspases after Asp-241 within the unique region of the protein.

GrpL Is Cleaved by Caspase 3-Like Proteases.

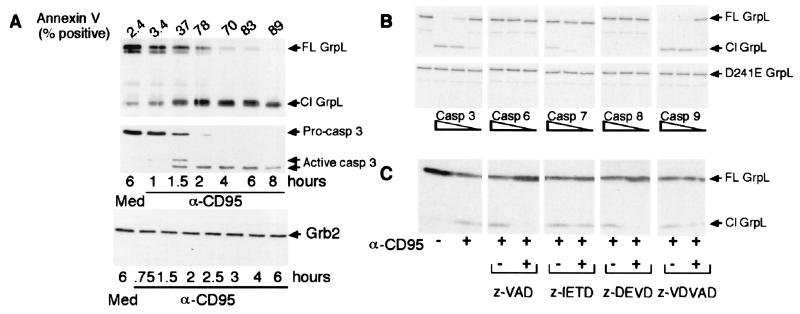

We next investigated the kinetics of GrpL cleavage in Jurkat and MP-1 cell lines. In both cell lines GrpL cleavage was detectable within 1 hr of incubation with CD95 mAb (Fig. 4A and data not shown). The kinetics of GrpL cleavage resembles that of caspase 3 activation as well as the cleavage of Mst1, a substrate of caspase 3 (data not shown and ref.13). These kinetics experiments suggest that GrpL is a substrate for an effector caspase such as caspase 3.

Figure 4.

GrpL is cleaved by caspase 3-like proteases. (A) Jurkat T cells were incubated with medium (Med) or 100 ng/ml CD95 mAb (α-CD95) for the indicated period. (Top) Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with GrpL mAb and Western blotted with GrpL antisera. Cell lysates were also Western blotted with anti-active caspase 3 (Middle), or anti-Grb2 (Bottom). Cells from each time point were also stained with annexin V. (B) Wild-type GrpL (Top) and D241E-GrpL (Bottom) were transcribed and translated in vitro as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting protein was then incubated in the presence of increasing amounts of the indicated caspase. (C) Jurkat T cells were incubated with the indicated inhibitor (1 μM) or DMSO for 3 hr before CD95 ligation. Cell lysates were separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blotted with anti-GrpL. The arrows indicate full-length (FL) and cleaved (Cl) protein.

To examine the specificity of the caspase or caspases that cleave GrpL, GrpL that had been transcribed and translated in vitro in the presence of [35S]methionine, was incubated with various recombinant caspases. Caspases 3 and 9 were able to efficiently cleave GrpL in vitro, whereas caspases 6 and 8 did not (Fig. 4B). Caspase 7 partially cleaved GrpL only at high doses. In contrast, caspases 6 and 7 efficiently cleaved Mst1 in vitro (data not shown), suggesting that GrpL is a selective substrate for caspases 3 and 9 in vitro.

We then tested the ability of selective caspase inhibitors to block GrpL cleavage in vivo. We used the general caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk, the caspase 8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk, the caspases 3, 6, and 7 inhibitor z-DEVD-fmk, and the caspase 2 inhibitor z-VDVAD-fmk. In CD95 mAb-treated Jurkat cells, z-VAD-fmk and z-DEVD-fmk completely inhibited detectable GrpL cleavage (Fig. 4C); in contrast, z-IETD-fmk and z-VDVAD-fmk prevented GrpL cleavage only at high doses. Because caspases 3 and 9 cleaved GrpL in vitro, and z-DEVD-fmk inhibited cleavage of GrpL in vivo, we conclude that caspase 3 or an enzyme with similar specificity cleaves GrpL after CD95 ligation. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the motif within GrpL that is cleaved, DINDG, resembles the consensus sequence for caspase 3 recognition (21).

CD95-Induced Caspase Activation Disrupts Signaling Complexes Necessary for TCR-Mediated Signaling Events.

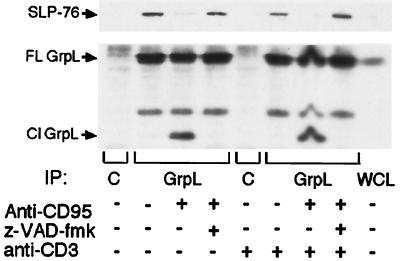

Cleavage of GrpL at Asp-241 by caspase 3-like proteases separates the C-terminal SH3 domain from the rest of the molecule. Because this domain has been shown to bind SLP-76, an adaptor protein critical for calcium signaling and NF-AT activation in T cells (5, 9), we tested whether cleavage of GrpL would disrupt the GrpL–SLP-76 complex. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments revealed that CD95-induced caspase activity results in a marked reduction of SLP-76 in the anti-GrpL immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5). There is a slight decrease in the amount of SLP-76 present in whole cell lysates derived from anti-CD95-treated cells (data not shown), but we have no direct evidence that SLP-76 is a caspase target. The interaction between these proteins is necessary for SLP-76 to be recruited to the membrane and to associate with the adaptor protein LAT (5, 8–10, 19, 20, 22). Thus, the ability of GrpL to interact with SLP-76 is critical for antigen receptor-induced calcium mobilization and NF-AT activation.

Figure 5.

CD95 ligation inhibits the interaction between GrpL and SLP-76. Jurkat cells were pretreated with z-VAD-fmk or DMSO for 3 hr before treatment with CD95 mAb. Anti-CD3 64.1 (2 μg/ml) was added for 2 hr. The cells were lysed, and the lysate was immunoprecipitated with GrpL mAb and Western blotted with SLP-76 Ab (Upper) or GrpL Ab (Lower). C indicates isotype control antibody and WCL indicates whole cell lysate. The arrows indicate full-length (FL) and cleaved (Cl) GrpL.

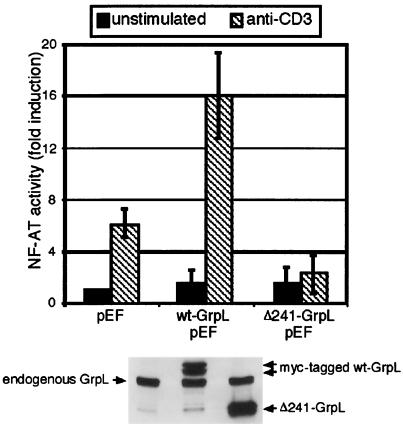

Truncated GrpL Inhibits TCR-Induced Signaling Events.

To test whether GrpL cleavage itself might play a role in the CD95-mediated desensitization of antigen receptor signaling, we generated a cDNA construct encoding the N-terminal cleavage product (Δ241-GrpL). Compared with vector control, wild-type GrpL markedly enhanced TCR-mediated NF-AT activity in Jurkat cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, Δ241-GrpL did not enhance this activation. In fact, NF-AT signaling in the presence of Δ241-GrpL was consistently lower when compared with the vector control. Thus, cleaved GrpL acts to inhibit signaling through the TCR.

Figure 6.

Truncated GrpL inhibits TCR-mediated NF-AT activation. (Upper) Jurkat T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid encoding the luciferase gene under control of the NF-AT promoter and either the empty pEF vector or the pEF vector containing wild-type GrpL, or the truncated form of GrpL (Δ241-GrpL). The cells were then stimulated with anti-CD3 for 6–8 hr. Luciferase activity was then measured. Luciferase activity in unstimulated cells transfected with the empty vector was normalized to 1. The data represented are the mean ± SD. (Lower) To verify expression, whole cell lysates from the samples transiently transfected with cDNA encoding the pEF empty vector (lane 1), wild-type GrpL (lane 2), and Δ241-GrpL (lane 3) were Western blotted with anti-GrpL.

Conclusions

The process of caspase-mediated inhibition of antigen receptor-mediated signaling events illustrates the cross-talk between these two receptor systems. The sequence or strength of stimulation through these receptors may dictate the cellular outcome. It has been previously demonstrated that antigen receptor ligation before CD95 inhibits the death signal from CD95 (3, 4). The data presented here indicate that ligation of CD95 before antigenic stimulation efficiently inhibits antigen receptor signaling pathways.

The CD95-mediated inhibition of observed antigen receptor signaling occurs at a time when the majority of cells remain viable and only approximately half of the GrpL molecules are cleaved (Fig. 4A). This observation suggests either that the truncated form of GrpL acts as a dominant negative or that GrpL cleavage is one component of a series of events by which CD95 down-regulates antigen receptor-induced signaling. CD95-induced caspase activity may target other molecules critical for antigen receptor-mediated signaling. For example, the ζ chain of the TCR, Fyn, and the inositol trisphosphate receptor are each substrates for caspases and are cleaved following CD95 ligation (23–25). Each cleavage product may act to inhibit signaling, but the presence of many caspase substrates in a signaling pathway provides an efficient mechanism by which CD95-induced caspase activity desensitizes antigen receptors.

Importantly, caspase-mediated proteolysis is a selective process. Unlike GrpL, the prototypical member of this protein family, Grb2, is not cleaved after CD95 ligation (Fig. 4A). This selectivity allows specific regulation of signaling pathways. For instance, certain pathways activated by the antigen receptor may be inhibited, whereas others remain inducible. Also, activation of a signaling pathway by one stimulus, such as the antigen receptor, may be inhibited, yet activation by other stimuli such as CD95 and by other receptor systems may be permitted.

In conclusion, this paper illustrates the reciprocal nature of the relationship between CD95 and the antigen receptor. Cross-linking the antigen receptor enhances expression of proteins that inhibit CD95-mediated apoptosis such as FLIP, Bcl-2, and FAIM (26). Conversely, CD95 ligation leads to the caspase-mediated cleavage of key signaling molecules involved in antigen receptor signaling. Through proteolysis of specific signaling molecules, such as GrpL, caspases selectively and efficiently modulate downstream signaling events to ensure the successful commitment of a cell to undergo apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Taunya Miller for her technical support. T.M.Y. is supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32AI70411. This research is funded by National Institutes of Health Grants AI45088, AI44250, and GM58487.

Abbreviations

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- SAPK

stress-activated protein kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- z

benzyloxycarbonyl

- fmk

fluoromethyl ketone

- TCR

T cell antigen receptor

References

- 1.Nagata S, Golstein P. Science. 1995;267:1449–1456. doi: 10.1126/science.7533326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornberry N A, Lazebnik Y. Science. 1998;281:1312–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathmell J C, Townsend S E, Xu J C, Flavell R A, Goodnow C C. Cell. 1996;87:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothstein T L, Wang J K, Panka D J, Foote L C, Wang Z, Stanger B, Cui H, Ju S T, Marshak-Rothstein A. Nature (London) 1995;374:163–165. doi: 10.1038/374163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law C L, Ewings M K, Chaunhary P M, Solow S A, Yun T J, Marshall A J, Hood L, Clark E A. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1243–1253. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S K, McGlade C J. Oncogene. 1998;17:3073–3082. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourette R P, Arnaud S, Myles G M, Blanchet J P, Rohrschneider L R, Mouchiroud G. EMBO J. 1998;17:7273–7281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asada H, Ishii N, Sasaki Y, Endo K, Kasai H, Tanaka N, Takeshita T, Tsuchiya S, Konno T, Sugamura K. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1383–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S K, Fang N, Koretzky G A, McGlade C J. Curr Biol. 1999;9:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Trible R P, Zhu M, Liu S K, McGlade C J, Samelson L E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23355–23361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000404200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aicher A, Shu G L, Magaletti D, Mulvania T, Pezzutto A, Craxton A, Clark E A. J Immunol. 1999;163:5786–5795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidorenko S P, Vetrova E P, Yurchenko O V, Berdova A G, Shlapatskaya L N, Gluzman D F. Neoplasma. 1992;39:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graves J D, Gotoh Y, Draves K E, Ambrose D, Han D K, Wright M, Chernoff J, Clark E A, Krebs E G. EMBO J. 1998;17:2224–2234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovitch P S, June C H, Grossmann A, Ledbetter J A. J Immunol. 1986;137:952–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.June C H, Rabinovitch P S. Methods Cell Biol. 1990;33:37–58. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs B, Tsokos G C. J Immunol. 1995;155:5543–5549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cahill M A, Peter M E, Kischkel F C, Chinnaiyan A M, Dixit V M, Krammer P H, Nordheim A. Oncogene. 1996;13:2087–2096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graves J D, Draves K E, Craxton A, Krebs E G, Clark E A. J Immunol. 1998;161:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boerth N J, Sadler J J, Bauer D E, Clements J L, Gheith S M, Koretzky G A. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1047–1058. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishiai M, Kurosaki M, Inabe K, Chan A C, Sugamura K, Kurosaki T. J Exp Med. 2000;192:847–856. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornberry N A, Chapman K T, Nicholson D W. Methods Enzymol. 2000;322:100–110. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)22011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yablonski D, Kuhne M R, Kadlecek T, Weiss A. Science. 1998;281:413–416. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gastman B R, Johnson D E, Whiteside T L, Rabinowich H. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1422–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricci J E, Maulon L, Luciano F, Guerin S, Livolsi A, Mari B, Breittmayer J P, Peyron J F, Auberger P. Oncogene. 1999;18:3963–3969. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirota J, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34433–34437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey G B, Donjerkovic D, Mueller C M, Liu S, Hinshaw J A, Tonnetti L, Davidson W, Scott D W. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:105–115. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]