Abstract

Understanding translational control in gene expression relies on precise and comprehensive determination of translation initiation sites (TIS) across the entire transcriptome. The recently developed ribosome-profiling technique enables global translation analysis, providing a wealth of information about both the position and the density of ribosomes on mRNAs. Here we present an approach, global translation initiation sequencing, applying in parallel the ribosome E-site translation inhibitors lactimidomycin and cycloheximide to achieve simultaneous detection of both initiation and elongation events on a genome-wide scale. This approach provides a view of alternative translation initiation in mammalian cells with single-nucleotide resolution. Systemic analysis of TIS positions supports the ribosome linear-scanning mechanism in TIS selection. The alternative TIS positions and the associated ORFs identified by global translation initiation sequencing are conserved between human and mouse cells, implying physiological significance of alternative translation. Our study establishes a practical platform for uncovering the hidden coding potential of the transcriptome and offers a greater understanding of the complexity of translation initiation.

Keywords: genome wide, high throughput, leaky scanning, start codon

Protein synthesis is the final step in the flow of genetic information and lies at the heart of cellular metabolism. Translation is regulated principally at the initiation stage, and during the last decade significant progress has been made in dissecting the role of initiation factors (eIFs) in the assembly of elongation-competent 80S ribosomes (1–3). However, mechanisms underlying start codon recognition are not fully understood. Proper selection of the translation initiation site (TIS) on mRNAs is crucial for the production of desired protein products. A fundamental and long-sought goal in understanding translational regulation is the precise determination of TIS codons across the entire transcriptome.

In eukaryotes, ribosomal scanning is a well-accepted model for start codon selection (4). During cap-dependent translation initiation, the small ribosome subunit (40S) is recruited to the 5′ end of mRNA (the m7G cap) in the form of a 43S preinitiation complex (PIC). The PIC is thought to scan along the message in search of the start codon. It is commonly assumed that the first AUG codon that the scanning PIC encounters serves as the start site for translation. However, many factors influence the start codon selection. For instance, the initiator AUG triplet usually is in an optimal context, with a purine at position −3 and a guanine at position +4 (5). The presence of an mRNA secondary structure at or near the TIS position also influences the efficiency of recognition (6). In addition to these cis sequence elements, the stringency of TIS selection also is subject to regulation by trans- acting factors such as eIF1 and eIF1A (7, 8). Inefficient recognition of an initiator codon results in a portion of 43S PIC continuing to scan and initiating translation at a downstream site, a process known as “leaky scanning” (4). However, little is known about the frequency of leaky scanning events at the transcriptome level.

Many recent studies have uncovered a surprising variety of potential translation start sites upstream of the annotated coding sequence (CDS) (9, 10). It has been estimated that about 50% of mammalian transcripts contain at least one upstream ORF (uORF) (11, 12). Intriguingly, many non-AUG triplets have been reported to act as alternative start codons for initiating uORF translation (13). Because there is no reliable way to predict non-AUG codons as potential initiators from in silico sequence analysis, there is an urgent need to develop experimental approaches for genome-wide TIS identification.

Ribosome profiling, based on deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (RPF), has proven to be powerful in defining ribosome positions on the entire transcriptome (14, 15). However, the standard ribosome profiling is not suitable for identifying TIS. Elevated ribosome density near the beginning of CDS is not sufficient for unambiguous identification of alternative TIS positions, in particular the TIS positions associated with overlapping ORFs. To overcome this problem, a recent study used an initiation-specific translation inhibitor, harringtonine, to deplete elongating ribosomes from mRNAs (16). This approach uncovered an unexpected abundance of alternative TIS codons, in particular non-AUG codons in the 5′ UTR. However, because the inhibitory mechanism of harringtonine on the initiating ribosome is unclear, whether the harringtonine-marked TIS codons truly represent physiological TIS remains to be confirmed.

We developed a technique, global translation initiation sequencing (GTI-seq), that uses two related but distinct translation inhibitors to differentiate ribosome initiation from elongation effectively. GTI-seq has the potential to reveal a comprehensive and unambiguous set of TIS codons at nearly single-nucleotide resolution. The resulting TIS maps provide a remarkable display of alternative translation initiators that vividly delineates the variation in start codon selection. This technique allows a more complete assessment of the underlying principles that specify start codon use in vivo.

Results

Experimental Design.

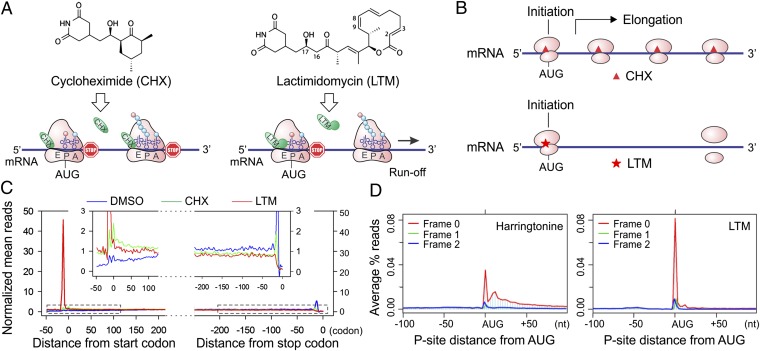

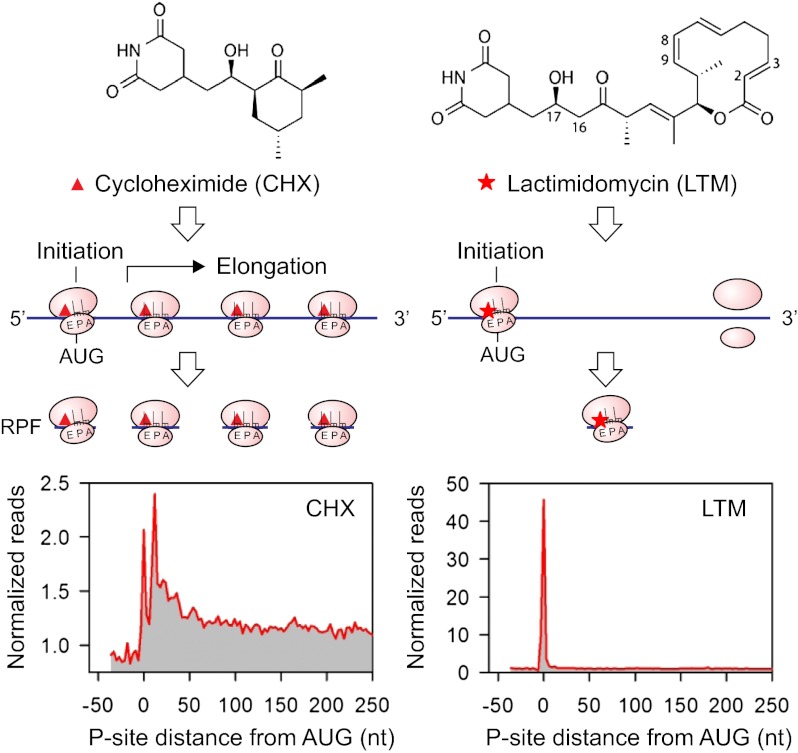

Cycloheximide (CHX) has been widely used in ribosome profiling of eukaryotic cells because of its potency in stabilizing ribosomes on mRNAs. Both biochemical (17) and structural studies (18) revealed that CHX binds to the exit (E)-site of the large ribosomal subunit, close to the position where the 3′ hydroxyl group of the deacylated transfer RNA (tRNA) normally binds. CHX thus prevents the release of deacylated tRNA from the E-site and blocks subsequent ribosomal translocation (Fig. 1A, Left). Recently, a family of CHX-like natural products isolated from Streptomyces was characterized, including lactimidomycin (LTM) (19, 20). Acting as a potent protein synthesis inhibitor, LTM uses a mechanism similar but not identical to that used by CHX (17). With its 12-member macrocycle, LTM is significantly larger in size than CHX (Fig. 1A). As a result, LTM cannot bind to the E-site when a deacylated tRNA is present. Only during the initiation step, in which the initiator tRNA enters the peptidyl (P)-site directly (21), is the empty E-site accessible to LTM. Thus, LTM acts preferentially on the initiating ribosome but not on the elongating ribosome. We reasoned that ribosome profiling using LTM in a side-by-side comparison with CHX should allow a complete segregation of the ribosome stalled at the start codon from the one in active elongation (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Experimental strategy of GTI-seq using ribosome E-site translation inhibitors. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for GTI-seq. Translation inhibitors CHX and LTM bind to the ribosome E-site, resulting in inhibition of translocation. CHX binds to all translating ribosomes (Left), but LTM preferentially incorporates into the initiating ribosomes when the E-site is free of tRNA (Right). (B) Ribosome profiling using CHX and LTM side by side allows the initiating ribosome to be distinguished from the elongating one. (C) HEK293 cells were treated with DMSO, 100 μM CHX, or 50 μM LTM for 30 min before ribosome profiling. Normalized RPF reads are averaged across the entire transcriptome, aligned at either their start site or stop codon from the 5′ end of RPFs. (D) Metagene analysis of RPFs obtained from HEK293 cells treated with harringtonine (Left) or LTM (Right). All mapped reads are aligned at the annotated start codon AUG, and the density of reads at each nucleotide position is averaged using the P-site of RPFs.

We designed an integrated GTI-seq approach and performed the ribosome profiling in HEK293 cells pretreated with either LTM or CHX. Although CHX stabilized the polysomes slightly compared with the no-drug treatment (DMSO), 30 min of LTM treatment led to a large increase in monosomes accompanied by a depletion of polysomes (Fig. S1). This result is in agreement with the notion that LTM halts translation initiation while allowing elongating ribosomes to run off (17). After RNase I digestion of the ribosome fractions, the purified RPFs were subjected to deep sequencing. As expected, CHX treatment resulted in an excess of RPFs at the beginning of ORFs in addition to the body of the CDS (Fig. 1C). Remarkably, LTM treatment led to a pronounced single peak located at the −12-nt position relative to the annotated start codon. This position corresponds to the ribosome P-site at the AUG codon when an offset of 12 nt is considered (14, 15). LTM treatment also eliminated the excess of ribosomes seen at the stop codon in untreated cells or in the presence of CHX. Therefore, LTM efficiently stalls the 80S ribosome at the start codons.

During the course of our study, Ingolia et al. (16) reported a similar TIS mapping approach using harringtonine, a different translation initiation inhibitor. One key difference between harringtonine and LTM is that the former drug binds to free 60S subunits (22), whereas LTM binds to the 80S complexes already assembled at the start codon (17). We compared the pattern of RPF density surrounding the annotated start codon in the published datasets (16) and the LTM results (Fig. S2). It appears that a considerable amount of harringtonine-associated RPFs are not located exactly at the annotated start codon. To compare the accuracy of TIS mapping accuracy by LTM and harringtonine directly, we performed ribosome profiling in HEK293 cells treated with harringtonine using the same protocol as in LTM treatment. As in the previous study, harringtonine treatment caused a substantial fraction of RPFs to accumulate in regions downstream of the start codon (Fig. 1D). The relaxed positioning of harringtonine-associated RPFs after prolonged treatment leaves uncertainty in TIS mapping. In contrast, GTI-seq using LTM largely overcomes this deficiency and offers high precision in global TIS mapping with single-nucleotide resolution (Fig. 1D).

Global TIS Identification by GTI-seq.

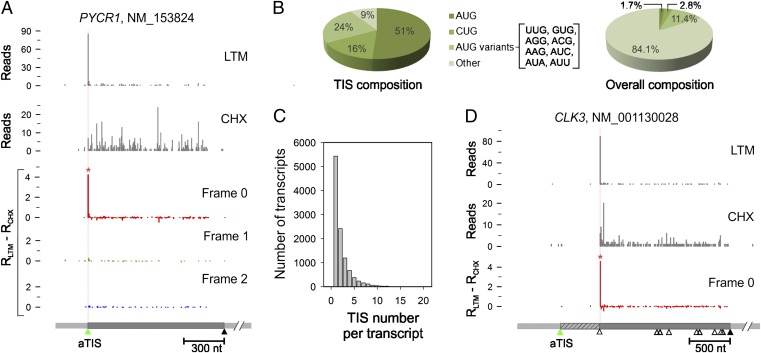

One of the advantages of GTI-seq is its ability to analyze LTM data in parallel with CHX. Because of the structural similarity between these two translation inhibitors, the LTM background reads resembled the pattern of CHX-associated RPFs (Fig. 2A). This feature allows us to reduce the background noise of LTM-associated RPFs further by subtracting the normalized density of CHX reads at every nucleotide position from the density of LTM reads at that position. A TIS peak then is called at a position in which the adjusted LTM reads density is well above the background (red asterisk in Fig. 2A; see Materials and Methods for details). From ∼10,000 transcripts with detectable TIS peaks, we identified a total of 16,863 TIS sites (Dataset S1). Codon composition analysis revealed that more than half the TIS codons used AUG as the translation initiator (Fig. 2B). GTI-seq also identified a significant proportion of TIS codons using near-cognate codons that differ from AUG by a single nucleotide, in particular CUG (16%). Remarkably, nearly half the transcripts (49.6%) contained multiple TIS sites (Fig. 2C), suggesting that alternative translation prevails even under physiological conditions. Surprisingly, over a third of the transcripts (42.3%) showed no TIS peaks at the annotated TIS position (aTIS) despite clear evidence of translation (Dataset S1). Although some could be false negatives resulting from the stringent threshold cutoff for TIS identification (Fig. S3), others were attributed to alternative translation initiation (see below). However, it is possible that some cases represent misannotation. For instance, the translation of CLK3 clearly starts from the second AUG, although the first AUG was annotated as the initiator in the current database (Fig. 2D). We found 50 transcripts that have possible misannotation in their start codons (Dataset S2). However, some mRNAs might have alternative transcript processing. In addition, we could not exclude the possibility that some of these genes might have tissue-specific TIS.

Fig. 2.

Global identification of TIS by GTI-seq. (A) TIS identification on the PYCR1 transcript. LTM and CHX reads are plotted as gray bar graphs. TIS identification is based on normalized density of LTM reads minus the density of CHX reads. The three reading frames are separated and presented as distinct colors. The identified TIS position is marked by a red asterisk and highlighted by a vertical line color-coded by the corresponding reading frame. The annotated coding region is indicated by a green triangle (start codon) and a black triangle (stop codon). (B) Codon composition of all TIS codons identified by GTI-seq (Left) is shown in comparison with the overall codon distribution over the entire transcriptome (Right). (C) Histogram showing the overall distribution of TIS numbers identified on each transcript. (D) Misannotation of the start codon on the CLK3 transcript. The annotated coding region is indicated by the green (start codon) and black (stop codon) triangles. AUG codons on the body of the coding region are also shown as open triangles. For clarity, only one reading frame is shown.

Characterization of Downstream Initiators.

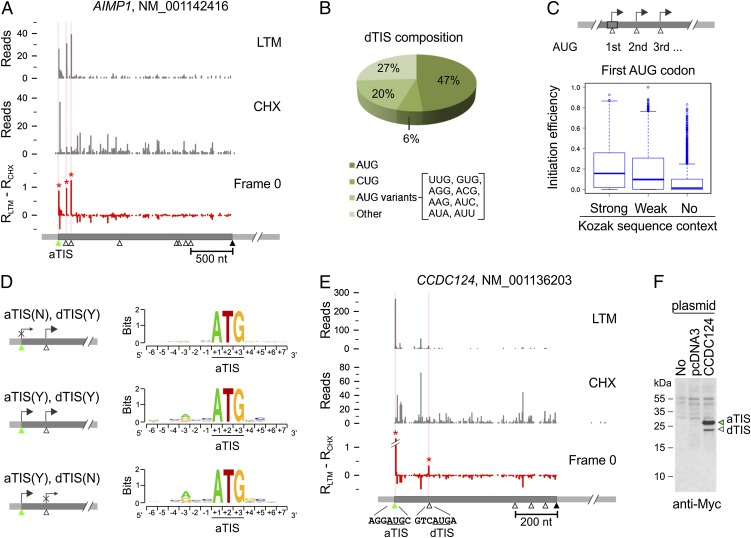

In addition to validating initiation at the annotated start codon, GTI-seq revealed clear evidence of downstream initiation on 27% of the analyzed transcripts with TIS peaks (Dataset S1). As a typical example, AIMP1 showed three TIS peaks exactly at the first three AUG codons in the same reading frame (Fig. 3A). Thus, the same transcript generates three isoforms of AIMP1 with varied NH2 termini, a finding that is consistent with the previous report (23). Of the total TIS positions identified by GTI-seq, 22% (3,741/16,863) were located downstream of aTIS codons; we termed these positions “dTIS.” Nearly half of the identified dTIS codons used AUG as the initiator (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of dTIS. (A) Identification of multiple TIS codons on the AIMP1 transcript. For clarity, only one reading frame is shown. (B) Codon composition of total dTIS codons identified by GTI-seq. (C) Relative efficiency of initiation at the first AUG codon with different Kozak sequence contexts (one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test: strong vs. weak: P = 7.92 × 10−24; weak vs. no Kozak context: P = 1.34 × 10−75). (D) Genes are grouped according to the identified initiation at an aTIS, at a dTIS, or at both. The sequence context surrounding the aTIS is shown as sequence logos. χ2 test, P = 2.57 × 10−100 for the −3 position and P = 3.95 × 10−18 for the +4 position. (E) Identification of multiple TIS codons on the CCDC124 transcript. (F) Validation of CCDC124 TIS codons by immunoblotting. The DNA fragment encompassing both the 5′ UTR and the CDS of CCDC124 was cloned and transfected into HEK 293 cells. Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using c-myc antibody.

What are the possible factors influencing downstream start codon selection? We classified genes with multiple TIS codons into three groups based on the Kozak consensus sequence of the first AUG. The relative leakiness of the first AUG codon was estimated by measuring the fraction of LTM reads at the first AUG over the total reads recovered on and after this position. The AUG codon with a strong Kozak sequence context showed higher initiation efficiency (or lower leakiness) than a codon with a weak or no consensus sequence (P = 1.12 × 10−142) (Fig. 3C). These results indicate the critical role of sequence context in start codon recognition. To substantiate this conclusion further, we performed a reciprocal analysis by grouping genes according to whether an initiation peak was identified at the aTIS or dTIS positions on their transcripts (Fig. 3D). A survey of the sequences flanking the aTIS revealed a clear preference of Kozak sequence context for different gene groups. We observed the strongest Kozak consensus sequence in the gene group with aTIS initiation but no detectable dTIS, (Fig. 3D, Bottom). This sequence context was largely absent in the group of genes lacking detectable translation initiation at the aTIS (Fig. 3D, Top). Thus, ribosome leaky scanning tends to occur when the context for an aTIS is suboptimal.

Cells use the leaky scanning mechanism to generate protein isoforms with changed subcellular localizations or altered functionality from the same transcript (24). GTI-seq revealed many more genes that produce protein isoforms via leaky scanning than had been previously reported (Dataset S1). For independent validation of the dTIS positions identified by GTI-seq, we cloned the gene CCDC124 whose transcript showed several initiation peaks above the background (Fig. 3E). One dTIS is in the same reading frame as the aTIS, allowing us to use a COOH-terminal tag to detect different translational products in transfected cells. Immunoblotting of transfected HEK293 cells showed two clear bands whose molecular masses correspond to full-length CCDC124 (28.9 kDa) and the NH2-terminally truncated isoform (23.7 kDa), respectively. Intriguingly, the relative abundance of both isoforms matched well to the density of corresponding LTM reads, suggesting that GTI-seq might provide quantitative assessment of translation initiation.

Characterization of Upstream Initiators.

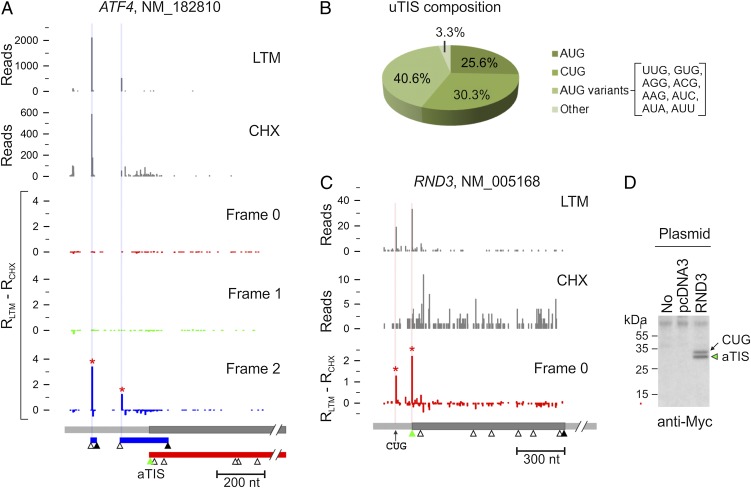

Sequence-based computational analyses predicted that about 50% of mammalian transcripts contain at least one uORF (11, 12). In agreement with this notion, GTI-seq revealed that 54% of transcripts bear one or more TIS positions upstream of the annotated start codon (Dataset S1). These upstream TIS (uTIS) codons, when outside the aTIS reading frame, often are associated with short ORFs. A classic example is ATF4, whose translation is controlled predominantly by several uORFs (25–27). This feature was clearly captured by GTI-seq (Fig. 4A). As expected, the presence of these uORFs efficiently repressed the initiation at the aTIS, as evidenced by few CHX reads along the CDS of ATF4.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of uTIS. (A) Identification of multiple TIS codons on the ATF4 transcript. Inset shows a region of frame 0 with the y axis enlarged 10-fold, showing the LTM peak at the annotated start codon AUG. Different ORFs are shown in boxes color-coded for the different reading frames. (B) Codon composition of total uTIS codons identified by GTI-seq. (C) Identification of multiple TIS codons on the RND3 transcript. (D) Validation of RND3 TIS codons by immunoblotting. The DNA fragment encompassing both the 5′ UTR and the CDS of RND3 was cloned and transfected into HEK 293 cells. Whole-cell lysates were immunoblotted using c-myc antibody.

Nearly half of the total TIS positions identified by GTI-seq were uTIS (7,936/16,863). In contrast to the dTIS, which used AUG as the primary start codon (Fig. 3B), the majority of uTIS (74.4%) were non-AUG codons (Fig. 4B). CUG was the most prominent of these AUG variants, with a frequency even higher than that of AUG (30.3% vs. 25.6%). In a few well-documented examples, the CUG triplet was reported to serve as an alternative initiator (13). To confirm experimentally the alternative initiators identified by GTI-seq, we cloned the gene RND3 that showed a clear initiation peak at a CUG codon in addition to the aTIS (Fig. 4C). The two initiators are in the same reading frame without a stop codon between them, thus permitting us to detect different translational products using an antibody against the fused COOH-terminal tag. Immunoblotting of transfected HEK293 cells showed two protein bands corresponding to the CUG-initiated long isoform (34 kDa) and the main product (31 kDa) (Fig. 4C). Once again, the levels of both isoforms were in accordance with the relative densities of LTM reads, further supporting the quantitative feature of GTI-seq in TIS mapping.

Global Impacts of uORFs on Translational Efficiency.

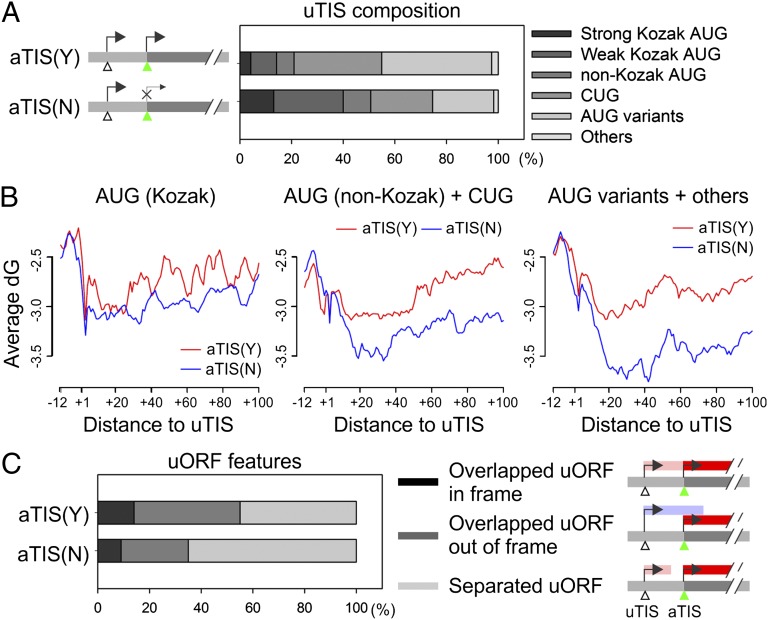

Initiation from an uTIS and the subsequent translation of the short uORF negatively influence the main ORF translation (10, 11). To find possible factors governing the alternative TIS selection in the 5′ UTR, we categorized uTIS-bearing transcripts into two groups according to whether initiation occurs at the aTIS and compared the sequence context of uTIS codons (Fig. 5A). For transcripts with initiation at both uTIS and aTIS positions [aTIS(Y)], the uTIS codons were preferentially composed of nonoptimal AUG variants. In contrast, the uTIS codons identified on transcripts with repressed aTIS initiation [aTIS(N)] showed a higher percentage of AUG with Kozak consensus sequences (P = 1.74 × 10−80). These results are in agreement with the notion that the accessibility of an aTIS to the ribosome for initiation depends on the context of uTIS codons.

Fig. 5.

Impact of uORF features on translational regulation. (A) The sequence composition of uTIS codons for genes with [aTIS(Y)] or without [aTIS(N)] aTIS initiation. Genes are classified into two groups based on aTIS initiation, and the uTIS sequence composition is categorized based on the consensus features shown on the right. (B) The contribution of mRNA secondary structure to TIS selection. Genes are grouped based on uTIS codon features listed in A. For each group, the transcripts with (red line) or without (blue line) aTIS initiation are analyzed for the averaged Gibbs free energy (ΔG) value in regions surrounding the identified uTIS codons. (C) The composition of uORFs in gene groups with or without aTIS initiation on their transcripts. Different ORF features are shown on the right.

Recent work showed a correlation between secondary structure stability of local mRNA sequences near the start codon and the efficiency of mRNA translation (28–30). To examine whether the uTIS initiation also is influenced by local mRNA structures, we computed the free energy associated with secondary structures from regions surrounding the uTIS position (Fig. 5B). We observed an increased folding stability of the region shortly after the uTIS in transcripts with repressed aTIS initiation (Fig. 5B, blue line). In particular, more stable mRNA secondary structures were present on transcripts with less optimal uTIS codons (Fig. 5B, Center and Right). Therefore, when the consensus sequence is absent from the start codon, the local mRNA secondary structure has a stronger correlation with the TIS selection.

Depending on the uTIS positions, the associated uORF can be separated from or overlap the main ORF. These different types of uORF could use different mechanisms to control the main ORF translation. For instance, when the uORF is short and separated from the main ORF, the 40S subunit can remain associated with the mRNA after termination at the uORF stop codon and can resume scanning, a process called “reinitiation” (2). When the uORF overlaps the main ORF, the aTIS initiation relies solely on the leaky scanning mechanism. We sought to dissect the respective contributions of reinitiation and leaky scanning to the regulation of aTIS initiation. Interestingly, we found a higher percentage of separated uORFs in aTIS(N) transcripts (Fig. 5C, P = 3.52 × 10−41). This result suggests that the reinitiation generally is less efficient than leaky scanning and is consistent with the negative role of uORFs in translation of main ORFs.

Cross-Species Conservation of Alternative Translation Initiators.

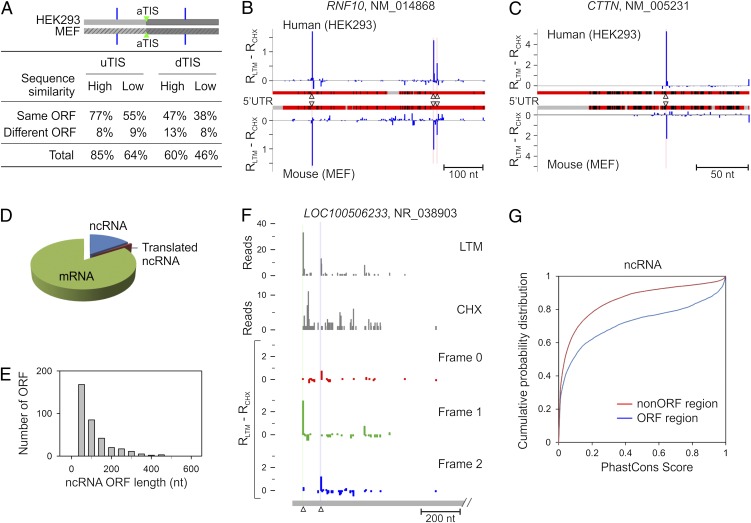

The prevalence of alternative translation reshapes the proteome landscape by increasing the protein diversity or by modulating translation efficiency. The biological significance of alternative initiators could be preserved across species if they are of potential fitness benefit. We applied GTI-seq to a mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cell line and identified TIS positions, including uTIS and dTIS, across the mouse transcriptome (Dataset S3). MEF cells showed remarkable similarity to HEK293 cells in overall TIS features (Fig. S4). For example, uTIS codons used non-AUG, especially CUG, as the dominant initiator. Additionally, about half the transcripts in MEF cells exhibited multiple initiators. Thus, the general features of alternative translation are well conserved between human and mouse cells.

To analyze the conservation of individual alternative TIS position on each transcript, we chose a total of 12,949 human/mouse orthologous mRNA pairs. We analyzed the 5′ UTR and CDS regions separately to measure the conservation of uTIS and dTIS positions, respectively (Fig. 6A). Each group was classified into two subgroups based on their sequence similarity. For genes with high sequence similarity, 85% of the uTIS and 60% of dTIS positions were conserved between human and mouse cells. Some of these alternative TIS codons were located at the same positions on the aligned sequences (Fig. S5). For example, RNF10 in HEK293 cells showed three uTIS positions, which also were found at the identical positions on the aligned 5′ UTR sequence of the mouse homolog in MEF cells (Fig. 6B). Remarkably, genes with low sequence similarity also displayed high TIS conservation across the two species (Fig. 6A). For instance, the 5′ UTR of the CTTN gene has low sequence identity between human and mouse homologs (alignment score = 40.3) (Fig. 6C). However, a clear uTIS was identified at the same position on the aligned region in both cells. Notably, the majority of alternative ORFs conserved between human and mouse cells were of the same type, i.e., either separated from or overlapping the main ORF (Fig. 6A and Fig. S5). The evolutionary conservation of those TIS positions and the associated ORFs is a strong indication of the functional significance of alternative translation in regulating gene expression.

Fig. 6.

Cross-species conservation of alternative TIS positions and identification of translated ncRNA. (A) Evolutionary conservation of alternative TIS positions identified by GTI-seq in HEK293 and MEF cells. Alternative uTIS and dTIS positions identified on human-mouse ortholog mRNA pairs are each classified into two subsets according to the alignment score of relevant sequences (5′ UTR for uTIS and CDS for dTIS). Each subset is divided further based on types of alternative ORFs. Percentage values are presented in the table. (B) Conservation of uTIS positions on the RNF10 transcript with high 5′ UTR sequence similarity between HEK293 and MEF cells. Red regions indicate matched sequences, black regions indicate mismatched sequences, and gray regions indicate sequence gaps. Identified uTIS positions are indicated by triangles. (C) Conservation of uTIS positions on the CTTN transcript with low sequence similarity of 5′ UTR between HEK293 and MEF cells. (D) Pie chart showing the relative percentage of mRNA, ncRNA and translated ncRNA identified by GTI-seq. (E) Histogram showing the overall length distribution of ORFs identified in ncRNAs. (F) Identification of multiple TIS positions on the ncRNA LOC100506233. (G) Evolutionary conservation of the ORF region on ncRNAs identified by GTI-seq. PhastCons scores are retrieved from the primate genome sequence alignment.

Characterization of Non-Protein Coding RNA Translation.

The mammalian transcriptome contains many non–protein-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) (31). ncRNAs have gained much attention recently because of increasing recognition of their role in a variety of cellular processes, including embryogenesis and development (32). Motivated by the recent report of the possible translation of large intergenic ncRNAs (16), we sought to explore the possible translation, or at least ribosome association, of ncRNAs in HEK293 cells. We selected RPFs uniquely mapped to ncRNA sequences to exclude the possibility of spurious mapping of reads originated from mRNAs. Of 5,763 ncRNAs annotated in RefSeq (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq/), we identified 228 ncRNAs (about 4%) that were associated with RPFs marked by both CHX and LTM (Fig. 6D and Dataset S4). Compared with protein-coding mRNAs, most ORFs recovered from ncRNAs were very short, with a median length of 54 nt (Fig. 6E). Several ncRNAs also showed alternative initiation at non-AUG start codons, as exemplified by LOC100506233 (Fig. 6F).

Comparative genomics reveals that the coding regions often are evolutionarily conserved elements (33). We retrieved the PhastCons scores (http://genome.ucsc.edu) for both coding and noncoding regions of ncRNAs and found that the ORF regions identified by GTI-seq indeed showed a higher conservation (Fig. 6G). Some ncRNAs showed a clear enrichment of highly conserved bases within the ORFs marked by both LTM and CHX reads (Fig. S6). Despite the apparent engagement by the protein synthesis machinery, the physiological functions of the coding capacity of these ncRNAs remain to be determined.

Discussion

The mechanisms of eukaryotic translation initiation have received increasing attention because of their central importance in diverse biological processes (1). The use of multiple initiation codons in a single mRNA contributes to protein diversity by expressing several protein isoforms from a single transcript. Distinct ORFs defined by alternative TIS codons also could serve as regulatory elements in controlling the translation of the main ORF (10, 11). Although we have some understanding of how ribosomes determine where and when to start initiation, our knowledge is far from complete. GTI-seq provides a comprehensive and high-resolution view of TIS positions across the entire transcriptome. The precise TIS mapping offers insights into the mechanisms of start codon recognition.

Global TIS Mapping at Single-Nucleotide Resolution by GTI-seq.

Traditional toeprinting analysis showed heavy ribosome pausing at both the initiation and the termination codons of mRNAs (34, 35). Consistently, deep sequencing-based ribosome profiling also revealed higher RPF density at both the start and the stop codons (14, 15). Although this feature enables approximate determination of decoded mRNA regions, it does not allow unambiguous identification of TIS positions, especially when multiple initiators are used. Translation inhibitors acting specifically on the first round of peptide bond formation allow the run-off of elongating ribosomes, thereby specifically halting ribosomes at the initiation codon. Indeed, harringtonine treatment caused a profound accumulation of RPFs in the beginning of CDS (16). A caveat regarding the use of harringtonine is that this drug binds to free 60S subunits, and the inhibitory mechanism is unclear. In particular, it is not known whether harringtonine completely blocks the initiation step. We observed that a significant fraction of ribosomes still passed over the start codon in the presence of harringtonine.

The translation inhibitor LTM has several features that contribute to the high resolution of global TIS identification. First, LTM binds to the 80S ribosome already assembled at the initiation codon and permits the formation of the first peptide bond (17). Thus, the LTM-associated RPF more likely represents physiological TIS positions. Second, LTM occupies the empty E-site of initiating ribosomes and thus completely blocks the translocation. This feature allows TIS identification at single-nucleotide resolution. With this precision, different reading frames become unambiguous, thereby revealing different types of ORFs within each transcript. Third, because of their similar structure and the use of the same binding site in the ribosome, LTM and CHX can be applied side by side to achieve simultaneous assessment of both initiation and elongation for the same transcript. With the high signal/noise ratio, GTI-seq offers a direct approach to TIS identification with minimal computational aid. From our analysis, the uncovering of alternative initiators allows us to explore the mechanisms of TIS selection. We also experimentally validated different translational products initiated from alternative start codons, including non-AUG codons. Further confirming the accuracy of GTI-seq, a sizable fraction of alternative start codons identified by GTI-seq exhibited high conservation across species. The evolutionary conservation strongly suggests a physiological significance of alternative translation in gene expression.

Diversity and Complexity of Alternative Start Codons.

GTI-seq revealed that the majority of identified TIS positions belong to alternative start codons. The prevailing alternative translation was corroborated by the finding that nearly half the transcripts contained multiple TIS codons. Although dTIS codons use the conventional AUG as the main initiator, a significant fraction of uTIS codons are non-AUG, with CUG being the most frequent one. In a few well-documented cases, including FGF2 (36), VEGF (37), and Myc (38), the CUG triplet was reported to serve as the non-AUG start codon. With the high-resolution TIS map across the entire transcriptome, GTI-seq greatly expanded the list of mRNAs with hidden coding potential not visible by sequence-based in silico analysis.

By what mechanisms are alternative start codons selected? GTI-seq revealed several lines of evidence supporting the linear-scanning mechanism for start codon selection. First, the uTIS context, such as the Kozak consensus sequence and the secondary structure, largely influenced the frequency of aTIS initiation. Second, the stringency of an aTIS codon negatively regulated the dTIS efficiency. Third, the leaky potential at the first AUG was inversely correlated with the strength of its sequence context. Because it is less likely that a preinitiation complex will bypass a strong initiator to select a suboptimal one downstream, it is not surprising that most uTIS codons are not canonical, whereas the dTIS codons are mostly conventional AUG. In addition to the leaky scanning mechanism for alternative translation initiation, ribosomes could translate a short uORF and reinitiate at downstream ORFs (2). After termination of a uORF is completed, it was assumed that some translation factors remain associated with the ribosome, facilitating the reinitiation process (39). However, this mechanism is widely considered to be inefficient. From the GTI-seq data set, about half the uORFs were separated from the main ORFs. Compared with transcripts with overlapping uORFs that must rely on leaky scanning to mediate the downstream translation, we observed repressed aTIS initiation in transcripts containing separated uORFs. It is likely that the ribosome reinitiation mechanism plays a more important role in selective translation under stress conditions (27).

Biological Impacts of Alternative Translation Initiation.

One expected consequence of alternative translation initiation is an expanded proteome diversity that has not been and could not be predicted by in silico analysis of AUG-mediated main ORFs. Indeed, many eukaryotic proteins exhibit a feature of NH2-terminal heterogeneity presumably caused by alternative translation. Protein isoforms localized in different cellular compartments are typical examples, because most localization signals are within the NH2-terminal segment (40, 41). Alternative TIS selection also could produce functionally distinct protein isoforms. One well-established example is C/EBP, a family of transcription factors that regulate the expression of tissue-specific genes during differentiation (42).

When an alternative TIS codon is not in the same frame as the aTIS, it is conceivable that the same mRNA will generate unrelated proteins. This production could be particularly important for the function of uORFs, which often are separated from the main ORF and encode short polypeptides. Some of these uORF peptide products control ribosome behavior directly, thereby regulating the translation of the main ORF. For instance, the translation of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase is subject to regulation by the six-amino acid product of its uORF (43). The alternative translational products also could function as biologically active peptides. A striking example is the discovery of short ORFs in noncoding RNAs of Drosophila that produce functional small peptides during development (44). However, both computational prediction and experimental validation of peptide-encoding short ORFs within the genome are challenging. Our study using GTI-seq represents a potential addition to the expanding ORF catalog by including ORFs from ncRNAs.

Perspective.

The enormous biological breadth of translational regulation has led to an enhanced appreciation of its complexities. However, current endeavors aiming to understand protein translation have been hindered by technological limitations. Comprehensive cataloging of global TIS and the associated ORFs is just the beginning step in unveiling the role of translational control in gene expression. More focused studies will be needed to decipher the function and regulatory mechanism of novel ORFs individually. A systematic, high-throughput method like GTI-seq offers a top-down approach, in which one can identify a set of candidate genes for intensive study. GTI-seq is readily applicable to broad fields of fundamental biology. For instance, applications of GTI-seq in different tissues will facilitate the elucidation of the tissue-specific translational control. The illustration of altered TIS selection under different growth conditions will set the stage for future investigation of translational reprogramming during organismal development as well as in human diseases.

Materials and Methods

HEK293 or MEF cells were treated with 100 μM CHX, 50 μM LTM, 2 μg/mL harringtonine, or DMSO at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were lysed in polysome buffer, and cleared lysates were separated by sedimentation through sucrose gradients. Collected polysome fractions were digested with RNase I, and the RPF fragments were size selected and purified by gel extraction. After the construction of the sequencing library from these fragments, deep sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSEQ. The trimmed RPF reads with final lengths of 26–29 nt were aligned to the RefSeq transcript sequences by Bowtie-0.12.7, allowing one mismatch. A TIS position on an individual transcript was called if the normalized density of LTM reads at the every nucleotide position minus the density of CHX reads at that position was well above the background. In the analysis of noncoding RNA, only reads unique to single ncRNA were used. To validate the identified TIS codons experimentally, specific genes encompassing both the 5′ UTR and the CDS were amplified by RT-PCR from total cellular RNAs extracted from HEK293 cells. The resultant cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA3.1 containing a c-myc tag at the COOH terminus. After transfection into HEK293 cells, whole-cell lysates were used for immunoblotting using anti-myc antibody. Full methods are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S.-B.Q. laboratory members for helpful discussions during the course of this study; Drs. Chaolin Zhang (Rockefeller University) and Adam Siepel (Cornell University) for critical reading of the manuscript; and the Cornell University Life Sciences Core Laboratory Center for performing deep sequencing. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants CA106150 (to B.S.) and 1 DP2 OD006449-01, Ellison Medical Foundation Grant AG-NS-0605-09, and Department of Defense Exploration-Hypothesis Development Award W81XWH-11-1-02368 (to S.-B.Q.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this work have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive database (accession no. SRA056377).

See Author Summary on page 14728 (volume 109, number 37).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1207846109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: Mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray NK, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozak M. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene. 2002;299:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kozak M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19867–19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozak M. Downstream secondary structure facilitates recognition of initiator codons by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8301–8305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maag D, Fekete CA, Gryczynski Z, Lorsch JR. A conformational change in the eukaryotic translation preinitiation complex and release of eIF1 signal recognition of the start codon. Mol Cell. 2005;17:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Marcos P, Cheung YN, Hinnebusch AG. Functional elements in initiation factors 1, 1A, and 2β discriminate against poor AUG context and non-AUG start codons. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4814–4831. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05819-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacono M, Mignone F, Pesole G. uAUG and uORFs in human and rodent 5’untranslated mRNAs. Gene. 2005;349:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris DR, Geballe AP. Upstream open reading frames as regulators of mRNA translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8635–8642. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8635-8642.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, Mootha VK. Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7507–7512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810916106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resch AM, Ogurtsov AY, Rogozin IB, Shabalina SA, Koonin EV. Evolution of alternative and constitutive regions of mammalian 5’UTRs. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Touriol C, et al. Generation of protein isoform diversity by alternative initiation of translation at non-AUG codons. Biol Cell. 2003;95:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(03)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell. 2011;147:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider-Poetsch T, et al. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation elongation by cycloheximide and lactimidomycin. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinge S, Voigts-Hoffmann F, Leibundgut M, Arpagaus S, Ban N. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic 60S ribosomal subunit in complex with initiation factor 6. Science. 2011;334:941–948. doi: 10.1126/science.1211204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju J, et al. Lactimidomycin, iso-migrastatin and related glutarimide-containing 12-membered macrolides are extremely potent inhibitors of cell migration. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1370–1371. doi: 10.1021/ja808462p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawara K, et al. Lactimidomycin, a new glutarimide group antibiotic. Production, isolation, structure and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1992;45:1433–1441. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steitz TA. A structural understanding of the dynamic ribosome machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:242–253. doi: 10.1038/nrm2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fresno M, Jiménez A, Vázquez D. Inhibition of translation in eukaryotic systems by harringtonine. Eur J Biochem. 1977;72:323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shalak V, Kaminska M, Mirande M. Translation initiation from two in-frame AUGs generates mitochondrial and cytoplasmic forms of the p43 component of the multisynthetase complex. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9959–9968. doi: 10.1021/bi901236g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochetov AV. Alternative translation start sites and hidden coding potential of eukaryotic mRNAs. Bioessays. 2008;30:683–691. doi: 10.1002/bies.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harding HP, Calfon M, Urano F, Novoa I, Ron D. Transcriptional and translational control in the Mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.011402.160624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudla G, Murray AW, Tollervey D, Plotkin JB. Coding-sequence determinants of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Science. 2009;324:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1170160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kochetov AV, et al. AUG_hairpin: Prediction of a downstream secondary structure influencing the recognition of a translation start site. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:318. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kertesz M, et al. Genome-wide measurement of RNA secondary structure in yeast. Nature. 2010;467:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature09322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattick JS. The functional genomics of noncoding RNA. Science. 2005;309:1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1117806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauli A, Rinn JL, Schier AF. Non-coding RNAs as regulators of embryogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:136–149. doi: 10.1038/nrg2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siepel A, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolin SL, Walter P. Signal recognition particle mediates a transient elongation arrest of preprolactin in reticulocyte lysate. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2617–2622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sachs MS, et al. Toeprint analysis of the positioning of translation apparatus components at initiation and termination codons of fungal mRNAs. Methods. 2002;26:105–114. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vagner S, et al. Translation of CUG- but not AUG-initiated forms of human fibroblast growth factor 2 is activated in transformed and stressed cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1391–1402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meiron M, Anunu R, Scheinman EJ, Hashmueli S, Levi BZ. New isoforms of VEGF are translated from alternative initiation CUG codons located in its 5’UTR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:1053–1060. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hann SR, King MW, Bentley DL, Anderson CW, Eisenman RN. A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt’s lymphomas. Cell. 1988;52:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pöyry TA, Kaminski A, Jackson RJ. What determines whether mammalian ribosomes resume scanning after translation of a short upstream open reading frame? Genes Dev. 2004;18:62–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.276504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang KJ, Wang CC. Translation initiation from a naturally occurring non-AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13778–13785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porras P, Padilla CA, Krayl M, Voos W, Bárcena JA. One single in-frame AUG codon is responsible for a diversity of subcellular localizations of glutaredoxin 2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16551–16562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Descombes P, Schibler U. A liver-enriched transcriptional activator protein, LAP, and a transcriptional inhibitory protein, LIP, are translated from the same mRNA. Cell. 1991;67:569–579. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill JR, Morris DR. Cell-specific translational regulation of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase mRNA. Dependence on translation and coding capacity of the cis-acting upstream open reading frame. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kondo T, et al. Small peptides switch the transcriptional activity of Shavenbaby during Drosophila embryogenesis. Science. 2010;329:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1188158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]