Abstract

Bacterial microcompartments (MCPs) are a widespread family of proteinaceous organelles that consist of metabolic enzymes encapsulated within a protein shell. For MCPs to function specific enzymes must be encapsulated. We recently reported that a short N-terminal targeting sequence of propionaldehyde dehydrogenase (PduP) is necessary and sufficient for the packaging of enzymes into a MCP that functions in 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD) utilization (Pdu) by Salmonella enterica. Here we show that encapsulation is mediated by binding of the PduP targeting sequence to a short C-terminal helix of the PduA shell protein. In vitro studies indicated binding between PduP and PduA (and PduJ) but not other MCP shell proteins. Alanine scanning mutagenesis determined that the key residues involved in binding are E7, I10, and L14 of PduP and H81, V84, and L88 of PduA. In vivo targeting studies indicated that the binding between the N terminus of PduP and the C terminus of PduA is critical for encapsulation of PduP within the Pdu MCP. Structural models suggest that the N terminus of PduP and C terminus of PduA both form helical structures that bind one another via the key residues identified by mutagenesis. Cumulatively, these results show that the N-terminal targeting sequence of PduP promotes its encapsulation by binding to MCP shell proteins. This is a unique report determining the mechanism by which a MCP targeting sequence functions. We propose that specific interactions between the termini of shell proteins and lumen enzymes have general importance for guiding the assembly and the higher level organization of bacterial MCPs.

Keywords: B12, carboxysome, drug delivery

Bacterial microcompartments (MCPs) are a diverse family of proteinaceous organelles used to optimize metabolic sequences that have toxic or volatile intermediates (1–5). They are polyhedral in shape, 100–150 nm in cross-section, and consist of a series of enzymes encapsulated within a protein shell. Such structures increase the local concentration of enzymes, facilitate substrate and cofactor transport between sequential enzymes, and protect cells from toxic metabolic intermediates (1, 2, 4, 5). On the basis of sequence analysis, it has been estimated that MCPs are produced by 20–25% of bacteria and function in 10 or more different metabolic processes (4, 6). Diverse MCPs play a major role in global carbon fixation (the carboxysome) (1, 3), are linked to pathogenesis by the enteric bacteria (7–9), and provide a unique basis for the development of synthetic subcellular chemical reactors and drug delivery vehicles (10–12).

Salmonella enterica produces a MCP for the B12-dependent catabolism of 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD) (13). The chemical 1,2-PD is a major product of the anaerobic degradation of common plant sugars rhamnose and fucose and is thought to be an important carbon and energy source in anoxic environments (14). The 1,2-PD utilization (Pdu) MCPs have a roughly polyhedral shape but are more irregular than carboxysomes (13, 15). They are composed of an outer shell built primarily from a few thousand small protein subunits that encapsulate a series of enzymes and cofactors required for metabolizing 1,2-PD (Fig. 1). The encapsulation of multiple enzymes involved in sequential reactions allows for effective channeling of intermediates between enzymes, leading to efficient metabolic throughput, while sequestering a cytotoxic pathway intermediate, propionaldehyde (15, 16). The outer shell of the Pdu MCP is thought to promote channeling by restricting the diffusion of propionaldehyde (17–19). The genes involved in 1,2-PD utilization (pdu) and MCP formation are found in a large contiguous cluster of 23 genes (13, 20–22). This locus encodes a transcriptional activator, a 1,2-PD diffusion facilitator, nine proteins thought to form the MCP shell, and enzymes for the degradation of 1,2-PD as well as for recycling coenzyme B12 (13).

Fig. 1.

Model for Pdu microcompartment. The hexagonal frame indicates the shell of the Pdu microcompartment, which is composed of nine different polypeptides (PduABB'JKMNTU). Encapsulated within the shell are enzymes for the activation of cob(III)alamin to coenzyme B12 (PduGH-S-O) as well as three 1,2-PD degradative enzymes: coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehydratase (PduCDE), propionaldehyde dehydrogenase (PduP), and 1-propanol dehydrogenase (PduQ). The proposed function of the Pdu MCP is to sequester propionaldehyde and channel it to downstream enzymes to prevent toxicity and DNA damage. A key requirement of this model is that specific enzymes are encapsulated within the protein shell. Enzymes not reported to be components of purified MCPs are positioned outside the MCP in the cytoplasm of the cell: phosphotransacylase (PduL) and propionate kinase (PduW).

A key requirement for MCP function is the encapsulation of specific enzymes within a protein shell. We recently showed that short N-terminal sequences of the PduP and PduD proteins are necessary and sufficient for the encapsulation of the PduP aldehyde dehydrogenase and PduCDE diol dehydratase within the Pdu MCP (23, 24). In addition, our bioinformatics analyses suggested that many other proteins are targeted to diverse MCPs via N-terminal targeting sequences and the functionality of some of these targeting sequences has been confirmed (23). Here, we show that the PduP enzyme is targeted into the Pdu MCP by binding interactions between its N-terminal targeting sequence and a short C-terminal region of the PduA shell protein. This is a unique report describing the mechanism by which MCP targeting sequences function. We propose that specific interactions between the termini of shell proteins and lumen enzymes have general importance for guiding both the assembly and the higher level organization of bacterial MCPs although other mechanisms are likely to be involved.

Results

PduP Interacts with PduA and PduJ.

Our prior studies showed that a short N-terminal sequence (18 amino acids) targets the PduP protein to the lumen of the Pdu MCP (23). We previously proposed that this targeting sequence might bind the interior surfaces of a shell protein to mediate packaging during shell assembly (23). To test whether PduP binds a particular Pdu shell protein or multiple shell proteins, nickel affinity pull downs were performed. In this test, binding is indicated for proteins that coelute with a His-tagged bait at high imidazole concentration (300 mM), whereas proteins that do not bind the bait pass through the column at low imidazole concentration (40 mM). PduP with a C-terminal His-tag (PduP-His6) was coproduced in vivo with the nine identified Pdu shell proteins PduA, PduB and PduB′, PduJ, PduK, PduM, PduN, PduT, and PduU, individually and cell extracts were prepared (PduB and PduB′ were produced together because they are encoded by overlapping genes) (25). Each extract was passed over a nickel column, the column was washed and eluted, and fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Results indicated that only PduA and PduJ coeluted with PduP-His6 at high concentrations of imidazole, indicating these two shell proteins could bind to PduP (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). A reciprocal experiment was performed by coproducing N-terminally His-tagged PduA or PduJ (His6-PduA or His6-PduJ) as bait and untagged PduP as prey. In this case, PduP again coeluted with His6-PduA or His6-PduJ at high imidazole concentration (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). Control experiments demonstrated that untagged PduA, PduJ, and PduP did not bind to the Ni-NTA column. Cumulatively, these results indicate interactions between the shell protein PduA or PduJ and the lumen enzyme PduP in vitro.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of His-tag pull downs used to test binding of PduA to PduP. Fractions that eluted from a Ni-NTA column at high imidazole concentrations are shown. Coelution of an untagged protein with a His-tagged bait indicates binding. M, molecular markers. Lane 1: PduP-His6 and PduA; lane 2: truncated PduP-His6 and PduA; lane 3: PduP-His6 and truncated PduA; lane 4: PduP and His6-PduA; lane 5: truncated PduP and His6-PduA; lane 6: PduP and truncated His6-PduA. A total of 5 μg of proteins was loaded in each lane. P, PduP; P′, truncated PduP, which has residues 2–18 deleted. A,PduA; A′, truncated PduA, which has 14 C-terminal amino acids deleted.

N-Terminal Targeting Sequence of the PduP Enzyme Mediates Binding to the PduA Shell Protein.

To test whether the N-terminal targeting sequence of PduP binds to PduA, PduP-His6 with 18 N-terminal amino acids deleted (signal-less) was analyzed using His-tag pull downs as described above. Prior studies showed that deleting the N terminus of PduP does not substantially affect its folding or activity (23). Nickel affinity pull-down tests indicated that PduA bound to full-length PduP-His6, but not to signal-less PduP-His6 (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2). A complementary experiment was done by coproducing His6-PduA with untagged full-length PduP and signal-less PduP. Results showed that full-length but not signal-less PduP bound to His6-PduA (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 5). Together, these results indicate that the N-terminal targeting sequence of PduP is required for binding of the PduP lumen enzyme to the PduA shell protein.

Short C-Terminal Helix of the PduA Shell Protein Is Required for Binding to the PduP Enzyme.

Prior crystallography studies suggested that the termini of BMC shell proteins might serve as binding sites for lumen enzymes (19). These termini tend to be disordered in crystal structures and to diverge in length and sequence, which would allow binding to the different enzymes that are found in varied MCPs. To test whether the C terminus of PduA binds to PduP, His6-PduA with 14 C-terminal residues deleted was analyzed by nickel affinity pull downs. Results showed that full-length but not C-terminally truncated PduA bound to PduP (Fig. 2, lane 4 and 6). The reciprocal experiment was performed by coproducing PduP-His6 and untagged full-length PduA or C-terminally truncated PduA. Again, in nickel affinity pull downs, C-terminally truncated PduA did not coelute with PduP-His6 (Fig. 2, lane 1 and 3). We also observed that truncated PduA was normally expressed and found in the soluble fraction indicating that the C-terminal deletion did not affect its expression or cause misfolding. Hence, these findings indicate that the 14 C-terminal amino acids of PduA are essential for binding to PduP in nickel affinity pull downs. Cumulatively, the above results indicate that interactions between the C terminus of PduA and the N terminus of PduP could mediate the binding of these proteins to one another in His-tag pull-down tests.

Key Amino Acids of the PduP Targeting Sequence.

To identify the key amino acids needed for targeting PduP to the lumen of the Pdu MCP, residues 2–18 of PduP were individually changed to alanine (alanine scanning mutagenesis) using mutagenic PCR primers. Wild-type PduP and each variant was produced from pLac22 in strains having a deletion of the chromosomal copy of pduP, and the resulting MCPs were purified and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and PduP enzyme assays (Fig. 3). When wild-type PduP protein was produced from pLac22 in the ΔpduP background, normal levels of PduP were present in purified MCPs based on both SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Among the PduP alanine scanning variants, three (E7A, I10A, and L14A) were found at substantially reduced levels in purified MCPs, indicating a possible targeting defect. The other alanine variants tested were present in purified MCPs in amounts roughly similar to wild-type PduP. A minor band is seen near the molecular mass of PduP even when its gene is deleted (no insert lane of SDS-PAGE gel). This band corresponds to the PduS cobalamin reductase (23).

Fig. 3.

Results for the alanine scanning mutagenesis of the N terminus of PduP. (A) SDS-PAGE and (B) Western blotting of purified MCPs. M, molecular markers; no insert, ΔpduP/plac22; WT, ΔpduP/plac22-pduP. Substitutions introduced into the targeting sequence of PduP are labeled for each lane. SDS-PAGE gel and Western blotting are aligned for each variant. A total of 10 μg of purified MCPs was loaded in each lane. (C) PduP enzyme activities for the cell extracts and purified MCPs. Dark columns represent the activities in crude extracts; light columns represent the activities in purified MCPs. Means and SEs are based on three replicates. (D) Multiple sequence alignment of the N-terminal regions of representative PduP homologs from different organisms. The National Center for Biotechnology Information gene accession identifications, beginning from the top entry, are 16765381, 365906594, 283832579, 311279056, 218549353, 238784333, 317491711, 365834525, and 237808453. *Three key amino acids for targeting PduP into the lumen of MCPs.

To get more accurate quantitative results, we also measured the PduP enzyme activity in both cell extracts and purified MCPs (Fig. 3C). Cell extracts from strains producing wild-type PduP and each alanine scanning variants all had similar activity. This established that all of the variants are stable and active and eliminated the possibility that they failed to associate with the Pdu MCP (in the experiments described above) due to low production, instability, or misfolding. Significantly, enzyme assays of MCPs purified from strains producing PduP variants E7A, I10A, and L14A all had much lower PduP enzyme activity than those purified from cells producing wild-type PduP. These findings supported the SDS-PAGE and Western blotting results and confirmed that residues E7, I10, and L14 of the PduP targeting sequence are critical for packaging of PduP to the lumen of the Pdu MCP. In addition, by aligning the sequences of PduP homologs that have the N-terminal extensions, we could see these three amino acids are conserved among different organisms (Fig. 3D and Table S1), suggesting a conserved targeting mechanism.

Key Amino Acid Residues in the C Terminus of PduA Required for Encapsulation of PduP.

Nickel affinity pull-down assays described above indicated that the C terminus of PduA was required for binding of PduA to the targeting sequence of PduP. This suggested that the C terminus of PduA might be needed for PduP encapsulation. By aligning the C-terminal sequences of PduA homologs, there are six amino acids conserved among different organisms (Fig. S2 and Table S2). Proline usually acts as a structure disruptor in the middle of regular secondary structural elements such as helices and sheets, so we targeted the other five conserved residues for mutagenesis (H81, V84, E85, I87, and L88). Each of these five residues was changed to alanine individually by introducing the appropriate scar-less mutations into the S. enterica chromosome. The resulting MCPs were purified and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 4 A and B). The PduP protein is clearly present in MCPs purified from the wild type, a PduA (E85A) variant, or a PduA (I87A) variant. In contrast, MCPs purified from three other PduA variants (H81A, V84A, or L88A) showed reduced band intensities both by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for the PduP protein, suggesting that these amino acids may be important for targeting the PduP enzyme to the Pdu MCP.

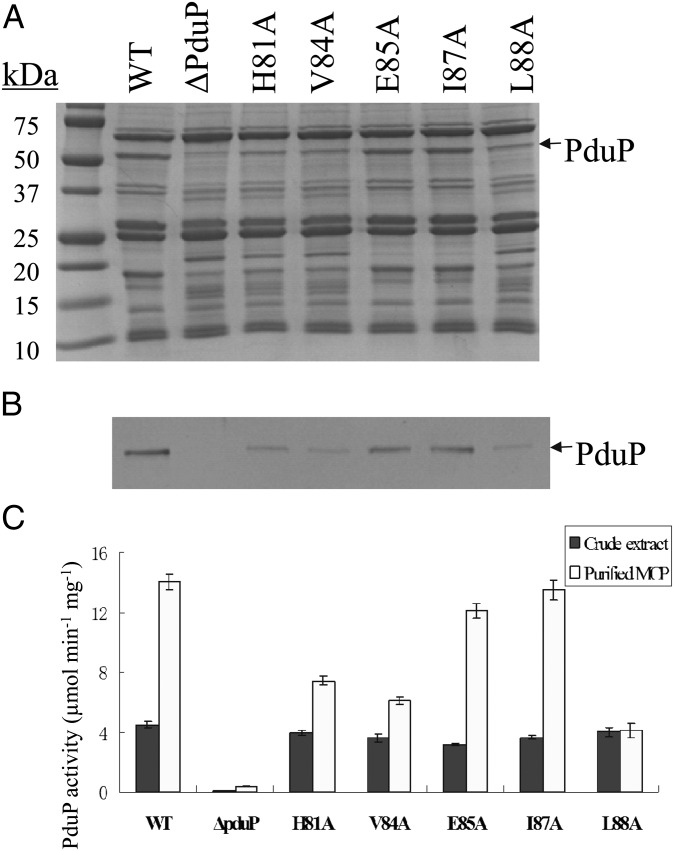

Fig. 4.

Results for the site-directed mutagenesis of the C terminus of PduA. (A) SDS-PAGE. (B) Western blotting of purified MCPs. M, molecular markers. Substitutions are labeled for each lane. SDS-PAGE gel and Western blotting are aligned for each variant. Ten milligrams of purified MCPs was loaded in each lane. (C) PduP enzyme activities for the cell extracts and purified MCPs. Dark columns represent the activities in crude extracts; light columns represent the activities in purified MCPs. Means and SEs are based on three replicates.

To get more accurate quantitative results, we also measured the PduP enzyme activity in both cell extracts and purified MCPs obtained from all five PduA variants (Fig. 4C). Crude cell extracts from each pduA variants all had similar PduP activity to that of the wild type. Significantly, MCPs purified from cells producing PduA variants H81, V84, or L88 individually all had lower PduP enzyme activity than that of the wild type. This supported the SDS-PAGE and Western blotting results, which indicated that residues H81, V84, and L88 of the PduA shell protein affect the targeting of the PduP enzyme to the lumen of the Pdu MCP.

We also note that PduA variants H81, V84, or L88 individually reduced but did not prevent PduP encapsulation. This could reasonably be explained by the binding of PduP to PduJ, another shell protein. Pull-down assays showed that PduP also binds the PduJ in vitro (Fig. S1). An alignment between PduA and PduJ sequences shows 83% identify with all three critical C-terminal binding residues conserved (Fig. S2). Hence, the binding of PduP and PduJ might account for the remaining PduP activity in MCPs purified from strains with PduA H81A, V84A, and L88A variants.

Structural Models of Binding Interaction Between the PduP and PduA Termini.

Findings described above indicated that binding interactions between the N terminus of PduP and the C terminus of PduA mediate packaging of PduP to the lumen of the Pdu MCP and that the key amino acids involved are E7, I10, and L14 of PduP and H81A, V84A, or L88A of PduA. To obtain a molecular picture of how this occurs, a structural model was developed. First, CD spectra were obtained for short synthetic peptides corresponding to the N terminus of PduP and its variants (Fig. S3). Results showed the wild-type sequence was strongly prone to helical structure (80%). The peptides with E7A, I10A, and L14A substitutions also preferred helical structures (71, 70, and 71% individually) indicating these substitutions have no major effects on the secondary structure. Because there is no crystal structure for the N-terminal region of PduP or its homologs, the PEPstr server was used to predict the structure of this short sequence (Fig. 5A) (26). Consistent with the CD spectra, the PEPstr sever indicated a helical structure. Interestingly, the three residues shown to be the most important for localization of PduP into the Pdu MCP (E7, I10, and L14) are located at one side of the helix forming an ideal interface for interacting with PduA (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Structure model of N terminus of PduP and its interaction with PduA. (A) Structural model of N terminus of PduP predicted by the PEPstr server. (B) Structure model of N terminus of PduP binding with the hexamer of PduA predicted by the RosettaDock server. Cyan color indicates the N terminus of PduP; gray, red, orange, golden, yellow, and blue color indicate the subunits of the PduA hexamer. (C) Structure model of N terminus of PduP binding with the monomer of PduA predicted by the RosettaDock server. Six key residues for binding are labeled.

The structure of PduA including its C-terminal region has been solved (27). It forms a symmetric hexamer with the C-terminal region solvent exposed and accessible for protein binding interactions (27). To model the interactions of PduP with PduA, the RosettaDock server was used to predict the binding of the N terminus of PduP (not the full-length protein sequence) to the hexamer of PduA, which is the biologically relevant unit (Fig. 5B) (28). The top-scoring model obtained shows the N terminus of PduP interacts with the C terminus of PduA, which also forms a helical structure. To simplify visualization of this interaction we also modeled binding N terminus of PduP and the PduA monomer (Fig. 5C). The key interacting residues were the same in both models: at the interface are E7, I10, and L14 on the N terminus of PduP and H81, V84, and I88 on the C terminus of PduA, which supports the mutagenesis studies described above. We also used the RosettaDock server to predict the effects of the key substitutions (E7A, I10A, or L14A) on the binding of N terminus of PduP with the PduA monomer. These single amino acid changes substantially altered the predicted binding pattern with PduA, which could account for the poor packaging of PduP in these variants (Fig. S4). Thus, structural modeling supports the in vitro and in vivo results described above.

It is important to note, however, that the structural model was based on the prediction of the binding of the N terminus of PduP (not full length of the PduP protein) and PduA. Hence, there will likely be some differences between the model and the in vivo binding. Crystallography studies are in progress to sort this out. Presumably, in vivo, the PduP targeting sequences would bind one or more of the six solvent-exposed C termini of the PduA hexamer (depending on the binding stoichiometry).

Discussion

A key question about bacterial MCPs is the mechanisms that govern their assembly and higher-level organization. Our prior work indicated that a short N-terminal targeting sequence was necessary and sufficient for the encapsulation of PduP (and heterologous enzymes) into the Pdu MCP (23). We also conducted bioinformatic analyses that indicted that similar N-terminal targeting sequences are widely used in diverse MCPs (23). Subsequent studies showed that several of these putative targeting sequences are able to mediate enzyme encapsulation into bacterial MCPs (24, 29). Furthermore, a new bioinformatic approach recently reported by Kerfeld and coworkers identified putative targeting peptides located in interdomain or C-terminal regions of MCP proteins; however, no experimental evidence was reported indicating that these peptides mediate the encapsulation of enzymes into bacterial MCPs (6).

Previously, we also proposed that the N-terminal targeting sequence of PduP might bind the interior of a shell protein to mediate encapsulation during assembly (23). In this report, we showed that the encapsulation of PduP within the Pdu MCP requires binding between its N-terminal targeting sequence and a short C-terminal helix of the PduA shell protein. Further studies indicated that the targeting sequence of PduP forms an α-helix in which three residues (E7, I10, and L14) form a key binding surface that interacts with the C-terminal helix of PduA primarily through residues H81, V84, and L88. Thus, it is likely that the N-terminal targeting sequence of the PduP enzyme binds the C-terminal tail of the PduA shell protein followed by encapsulation of PduP during MCP assembly. A related mechanism might apply to other MCP proteins. A recent bioinformatic study indicated that a propensity to form α-helixes is a conserved feature of MCP targeting sequences and that a putative targeting sequence on the C terminus of the carboxysome protein CcmN binds to shell protein CcmK2; however, the details of how CcmN binds CcmK2 were not determined (6).

Recently, we reported that the N-terminal region of the medium subunit (PduD) mediates encapsulation of diol dehydratase (PduCDE) into the Pdu MCP (24). An alignment of PduD and PduP shows that their N-terminal targeting sequences have a similar pattern of alternating charged and hydrophobic residues (Fig. S5). Furthermore, modeling indicates that the targeting sequence of PduD also forms an α-helix as that was found for PduP (Fig. S6). Interestingly, however the three key shell binding residues found in the PduP targeting sequence (E7, I10, and L14) show two conservative replacements in the PduD targeting sequence (I > L and L > I). These changes could alter the binding properties of the PduD targeting sequence such that it binds a different cognate shell protein than does PduP. Thus, variations in targeting sequences might be used to guide the encapsulation of several different enzymes into a particular MCP.

On the basis of the studies described above and prior work, we propose that N-terminal targeting sequences play a key role in both the assembly and the higher-order structure of bacterial MCPs. We suggest the shell of the Pdu MCP (which is composed of up to nine different shell proteins formed from nine distinct polypeptides) has a well-ordered structure. We further propose that specific targeting sequences bind to particular cognate shell proteins such that the organization of the encapsulated enzymes mirrors the organization of the cognate shell proteins within the shell. Both targeting peptides and shell protein termini vary substantially in sequence, which could provide the needed variation in binding specificity (23, 24). The need for binding specificity could help to explain why the Pdu MCP is constructed from up to nine different shell polypeptides (13, 30). Furthermore, binding of particular lumen enzymes to cognate shell proteins could be used to orient sequential catalytic sites as well as the pores proposed to conduct enzyme substrates and cofactors across the shell (17–19). Thus, the MCP’s shell might serve as scaffold on which proteins are arrayed via their targeting sequences followed by encapsulation during assembly.

Although several studies have shown that targeting sequences play a prominent role in MCP assembly, it seems clear that other mechanisms are also involved. A number of MCP-associated enzymes lack recognizable targeting sequences, although new variations may remain to be identified (23). Studies by Price and coworkers with Synechococcus PCC7942 showed that the putative shell protein CcmM (which is not known to have a targeting sequence) is a focal point for determining the organization of the β-carboxysome (31). CcmM binds multiple carboxysome proteins and is thought to cross-link carbonic anhydrase (CA) and ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase monooxygenase (RubisCO) into an ordered network that plays a key role in carboxysome assembly (31). Similarly, in Synechocystis PCC6803, CcmM was shown to be critical to the formation of a bicarbonate dehydration complex (BDC) consisting of a CA dimer, a CcmM trimer, and the putative carboxysome shell protein CcmN (32). In this case, CcmM was shown to directly bind the CcmK and CcmL shell proteins and it was proposed that the BCD is used to help organize the carboxysome and recruit CA to shell (32). In addition, recent studies showed that CcmN (which is part of the BDC) binds the carboxysome shell protein CcmK2 via a short C-terminal peptide related to the PduP targeting sequence (6). Thus, studies to date indicated that cross-linking proteins, targeting peptides, and perhaps additional systems work together to mediate the assembly and define the architecture of bacterial MCPs.

A final important point is that the binding of the PduP with the C terminus of PduA indicates that the C terminus of PduA is on the interior surface of the MCP shell; hence, the concave face of the PduA hexamer (i.e., the C- and N termini) lines the MCP interior (19). To our knowledge, this is unique evidence supporting a specific orientation for a shell protein having a bacterial microcompartment (BMC) domain. This is a key aspect of shell function that might generally apply to the BMC family of proteins, the major class of proteins that makes up MCP shells.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Methods and Protein Analyses.

Plasmid purification gel electrophoresis and other molecular biology protocols were carried out using standard methods (33). For alanine scanning mutagenesis, base changes were introduced in PCR primers. Microcompartments were purified as described and stored at 4 °C before analysis (30). PduP enzyme assays, SDS-PAGE, protein assays, and other general protein methods were carried out as described (34, 35). CD spectra were determined as described and data were analyzed with JFIT software (36). The strains used in this study are listed in Table S3.

Protein Purification and Nickel-Affinity Pull-Down Assay.

Desired proteins were cloned into pCDFDuet-1 (Novagen) and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta 2 cells (Stratagene). The transformants were grown in 400 mL of Luria–Bertani medium until OD600 of 0.6 when protein production was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16 °C for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The cell paste was suspended in 10 mL of 50 mM 2-(Cyclohexylamino) ethanesulfonic acid (CHES) (pH 8.5), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and broken with a French press (Thermo Electron) operated at 20,000 psi. The crude cell extract was centrifuged at 35,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to separate the soluble and insoluble fractions. The supernatant was loaded onto a column containing 4 mL Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen) previously equilibrated with 50 mM CHES (pH 8.5), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole. The column was washed with 20 mL of 50 mM CHES (pH 8.5), 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, and then the enzyme bound to the column was eluted with 2 mL 50 mM CHES (pH 8.5), 300 mM NaCl, and 300 mM imidazole. All elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE to test for coelution of the His-tagged and untagged protein.

Structural Modeling.

PEPstr server was used to predict the structure of short peptides as described in SI Materials and Methods. The RosettaDock server (http://rosettadock.graylab.jhu.edu) was used to predict the binding of the targeting sequence of PduP or its variants to the PduA monomer and hexamer. In all cases, the top-scoring model is presented (SI Materials and Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Protein and DNA facilitities at Iowa State University (Ames, IA) for help with CD spectra and DNA sequencing. This project was funded by Grant AI081146 from the National Institutes of Health (to T.A.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1207516109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. Bacterial microcompartments. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:391–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Protein-based organelles in bacteria: Carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price GD, Badger MR, Woodger FJ, Long BM. Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): Functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1441–1461. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng S, Liu Y, Crowley CS, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Bacterial microcompartments: their properties and paradoxes. Bioessays. 2008;30:1084–1095. doi: 10.1002/bies.20830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobik TA. Polyhedral organelles compartmenting bacterial metabolic processes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:517–525. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinney JN, Salmeen A, Cai F, Kerfeld CA. Elucidating essential role of conserved carboxysomal protein CcmN reveals common feature of bacterial microcompartment assembly. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17729–17736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conner CP, Heithoff DM, Julio SM, Sinsheimer RL, Mahan MJ. Differential patterns of acquired virulence genes distinguish Salmonella strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4641–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joseph B, et al. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes contributing to intracellular replication by expression profiling and mutant screening. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:556–568. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.556-568.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiennimitr P, et al. Intestinal inflammation allows Salmonella to use ethanolamine to compete with the microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17480–17485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107857108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corchero JL, Cedano J. Self-assembling, protein-based intracellular bacterial organelles: Emerging vehicles for encapsulating, targeting and delivering therapeutical cargoes. Microb Cell Fact. 2011;10:92. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dueber JE, et al. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papapostolou D, Howorka S. Engineering and exploiting protein assemblies in synthetic biology. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:723–732. doi: 10.1039/b902440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobik TA, Havemann GD, Busch RJ, Williams DS, Aldrich HC. The propanediol utilization (pdu) operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 includes genes necessary for formation of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent 1, 2-propanediol degradation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5967–5975. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5967-5975.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obradors N, Badía J, Baldomà L, Aguilar J. Anaerobic metabolism of the L-rhamnose fermentation product 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2159–2162. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2159-2162.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havemann GD, Sampson EM, Bobik TA. PduA is a shell protein of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent degradation of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1253–1261. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1253-1261.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson EM, Bobik TA. Microcompartments for B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation provide protection from DNA and cellular damage by a reactive metabolic intermediate. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/JB.01925-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerfeld CA, et al. Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles. Science. 2005;309:936–938. doi: 10.1126/science.1113397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinney JN, Axen SD, Kerfeld CA. Comparative analysis of carboxysome shell proteins. Photosynth Res. 2011;109:21–32. doi: 10.1007/s11120-011-9624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeates TO, Thompson MC, Bobik TA. The protein shells of bacterial microcompartment organelles. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bobik TA, Xu Y, Jeter RM, Otto KE, Roth JR. Propanediol utilization genes (pdu) of Salmonella typhimurium: three genes for the propanediol dehydratase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6633–6639. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6633-6639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeter RM. Cobalamin-dependent 1,2-propanediol utilization by Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:887–896. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-5-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen P, Andersson DI, Roth JR. The control region of the pdu/cob regulon in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5474–5482. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5474-5482.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan C, et al. Short N-terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7509–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan C, Bobik TA. The N-terminal region of the medium subunit (PduD) packages adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydratase (PduCDE) into the Pdu microcompartment. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5623–5628. doi: 10.1128/JB.05661-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Havemann GD, Bobik TA. Protein content of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B12-dependent degradation of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5086–5095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5086-5095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur H, Garg A, Raghava GPS. PEPstr: A de novo method for tertiary structure prediction of small bioactive peptides. Protein Pept Lett. 2007;14:626–631. doi: 10.2174/092986607781483859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley CS, et al. Structural insights into the mechanisms of transport across the Salmonella enterica Pdu microcompartment shell. J Biochem. 2010;285:37838–37846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyskov S, Gray JJ. The RosettaDock server for local protein-protein docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W233-8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choudhary S, Quin MB, Sanders MA, Johnson ET, Schmidt-Dannert C. Engineered protein nano-compartments for targeted enzyme localization. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinha S, Cheng S, Fan C, Bobik TA. The PduM protein is a structural component of the microcompartments involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation by Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1912–1918. doi: 10.1128/JB.06529-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long BM, Badger MR, Whitney SM, Price GD. Analysis of carboxysomes from Synechococcus PCC7942 reveals multiple Rubisco complexes with carboxysomal proteins CcmM and CcaA. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29323–29335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cot SS, So AK, Espie GS. A multiprotein bicarbonate dehydration complex essential to carboxysome function in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:936–945. doi: 10.1128/JB.01283-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walter D, Ailion M, Roth J. Genetic characterization of the pdu operon: Use of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1013–1022. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1013-1022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, et al. PduL is an evolutionarily distinct phosphotransacylase involved in B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation by Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1589–1596. doi: 10.1128/JB.01151-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan C, Fromm HJ, Bobik TA. Kinetic and functional analysis of L-threonine kinase, the PduX enzyme of Salmonella enterica. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20240–20248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.