Abstract

Basophils are powerful mediators of Th2 immunity and are present in increased numbers during allergic inflammation and helminth infection. Despite their ability to potentiate Th2 immunity the mechanisms regulating basophil development remain largely unknown. We have found a unique role for isotype-switched antibodies in promoting helminth-induced basophil production following infection of mice with Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri or Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophil expansion was found to occur within the bone marrow, and to a lesser extent the spleen, and was IL-3 dependent. IL-3 was largely produced by CD4+CD49b+NK1.1− effector T cells at these sites, and required the IL-4Rα chain. However, antibody-deficient mice exhibited defective basophil mobilization despite intact T-cell IL-3 production, and supplementation of mice with immune serum could promote basophilia independently of required IL-4Rα signaling. Helminth-induced eosinophilia was not affected by the deficiency in isotype-switched antibodies, suggesting a direct effect on basophils rather than through priming of Th2 responses. Although normal type 2 immunity occurred in the basopenic mice following primary infection with H. polygyrus bakeri, parasite rejection following challenge infection was impaired. These data reveal a role for isotype-switched antibodies in promoting basophil expansion and effector function following helminth infection.

Keywords: hematopoesis, Fc receptors, IgG1, IgE

Basophils are rare granulocytes representing less than 0.3% of peripheral blood leukocytes (1). They develop from hematopoietic stem cells and typically complete their maturation in the bone marrow before entering the circulation as fully matured cells (2). Basophils can be activated by cross-linking of IgE receptors, C5a, Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, or helminth antigens, resulting in degranulation and the release of vasoactive substances including histamine, cytokine production (particularly IL-4), and the synthesis of lipid mediators. Together these responses result in enhanced Th2 immunity and inflammation (2).

Murine basophils are continuously present within the circulation, but their number increases dramatically following helminth infection and during allergic inflammation. They have also been proposed to be potent modulators of Th2 immunity as they represent a significant source of IL-4 in vivo and may in some circumstances cooperate with dendritic cells to initiate Th2 immune responses (3, 4). As effector cells, basophils contribute to allergic inflammation and play a role during IgG-mediated anaphylaxis (5), chronic allergic dermatitis (6, 7), and allergic airway inflammation (3). Basophils have also been reported to play a nonredundant role in acquired immunity against helminths (7–10) and ticks (11).

IL-3 plays a crucial role in basophil biology and can “prime” enhanced IL-4 production following antibody-mediated activation (12, 13). Moreover, IL-3 selectively increases the number of mature basophils that can be derived from bone marrow cells in vitro (14) and in vivo (15), and IL-3–deficient mice fail to exhibit increased basophil numbers following infection with the helminths Strongyloides venezuelensis or Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (16). However, IL-3 does not appear to be required for basophil production during steady state conditions (16) and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), but not IL-3, has recently been reported to be required for Trichuris muris-induced basophilia (17).

In the current study we show a unique role for circulating isotype switched antibodies in promoting basophil expansion following Heligmosomoides polygyrus bakeri and N. brasiliensis infection. Although H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia was IL-3 dependent the ability of antibodies to promote basophilia following H. polygyrus bakeri was uncoupled from T-cell IL-3 production. Consistent with several previous reports investigating the role of basophils during N. brasiliensis infection (7, 10), basophils were not necessary for the development of type 2 immunity following primary H. polygyrus bakeri infection, however they promoted worm rejection following challenge infection.

Results

Isotype-Switched Antibodies Support Helminth-Induced Basophil Expansion.

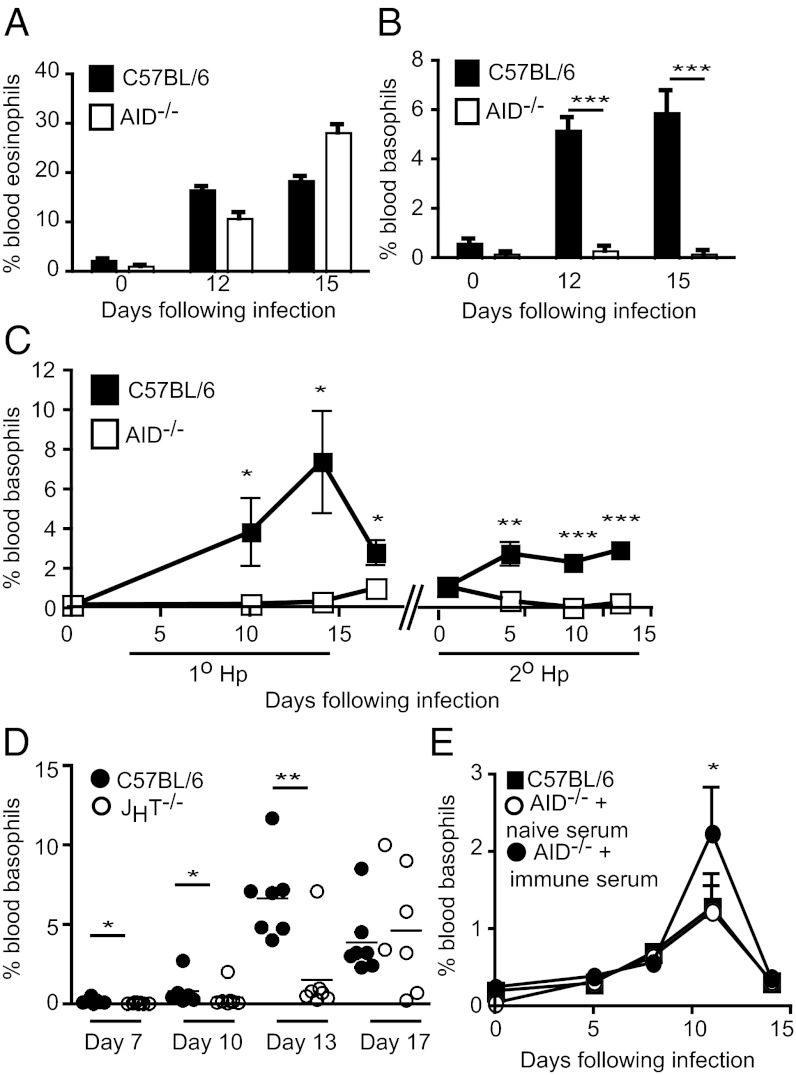

We previously reported a crucial role for isotype switched antibodies in providing protective immunity against the enteric helminth H. polygyrus bakeri (18). To further assess the role of such antibodies, we used AID−/− mice, which contain normal numbers of B cells and IgM-secreting plasma cells, but have lost the ability to undergo isotype class switching or somatic hypermutation (19). Differential cell counting of Diff Quik-stained blood smears (Fig. S1) from C57BL/6 or AID−/− mice revealed comparable increases in circulating eosinophils following helminth infection (Fig. 1A), however no increase in the percentage of circulating basophils was observed in AID−/− mice (Fig. 1B). This finding was additionally verified using flow cytometry (Fig. S1 and Fig. 1C) and a similar abrogation of the basophil response was noted following secondary infection of AID−/− mice (Fig. 1C). We additionally investigated the basophil response in JHT−/− mice, which completely lack B cells (20). All but one JHT−/− mouse failed to mobilize basophils at the peak of the response in wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1D). However, by day 17 postinfection, five of seven JHT−/− mice exhibited basophilia, albeit with a great deal of variability observed between individual animals. These data collectively indicated that antibodies are not absolutely necessary for—but can contribute to—helminth-induced basophilia. In keeping with this conclusion, antibodies were not essential for N. brasiliensis-induced basophil expansion; however, the addition of immune serum to N. brasiliensis-infected AID−/− mice significantly enhanced basophil numbers (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Basophilia is selectively impaired in helminth-infected AID−/− and JHT−/− mice. (A–C) C57BL/6 and AID−/− mice were infected with 200 L3 H. polygyrus bakeri. At the indicated time points following infection, the percentage of blood (A) eosinophils or (B) basophils was determined by differential cell counting of blood smears, and (C) percentage of basophils was additionally assessed by flow cytometry. (D) C57BL/6 and JHT−/− mice were infected with 200 L3 H. polygyrus bakeri and the percentage of basophils in the blood was determined by flow cytometry. (E) C57BL/6 and AID−/− mice were infected with 500 L3 N. brasiliensis with or without immune serum supplementation, and the percentage of basophils in the blood was determined by flow cytometry. All data are shown as the combined mean ± SEM of individual mice (n = 3–7 mice per group) from one experiment and are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Although the variance between AID−/− and JHT−/− cannot be readily explained, one obvious difference between these mice is the ability of AID−/− but not JHT−/− mice to make IgM. Analysis of serum from AID−/− mice indicated that they could also generate IgM specific for H. polygyrus bakeri antigens (Fig. S2). Thus, the B-cell–deficient JHT−/− mice are likely to exhibit increased and/or prolonged levels of circulating antigens compared with either wild type or AID−/− mice and this antigen may act independently of antibodies to promote the late basophil response observed in these mice. To determine the presence of soluble antigen, we took advantage of the recently generated monoclonal antibodies exhibiting specificity against H. polygyrus bakeri excretory–secretory (HES) proteins (21). As expected, increased quantities of soluble helminth antigens were detected in the serum of B-cell–deficient, μMT mice, compared with C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S2). That antibodies were resulting in enhanced antigen clearance by forming immune complexes was additionally demonstrated by the finding that heat treatment of wild-type serum results in increased levels of soluble antigen (Fig. S2).

H. polygyrus bakeri Promotes Basophil Expansion Within the Bone Marrow and Spleen.

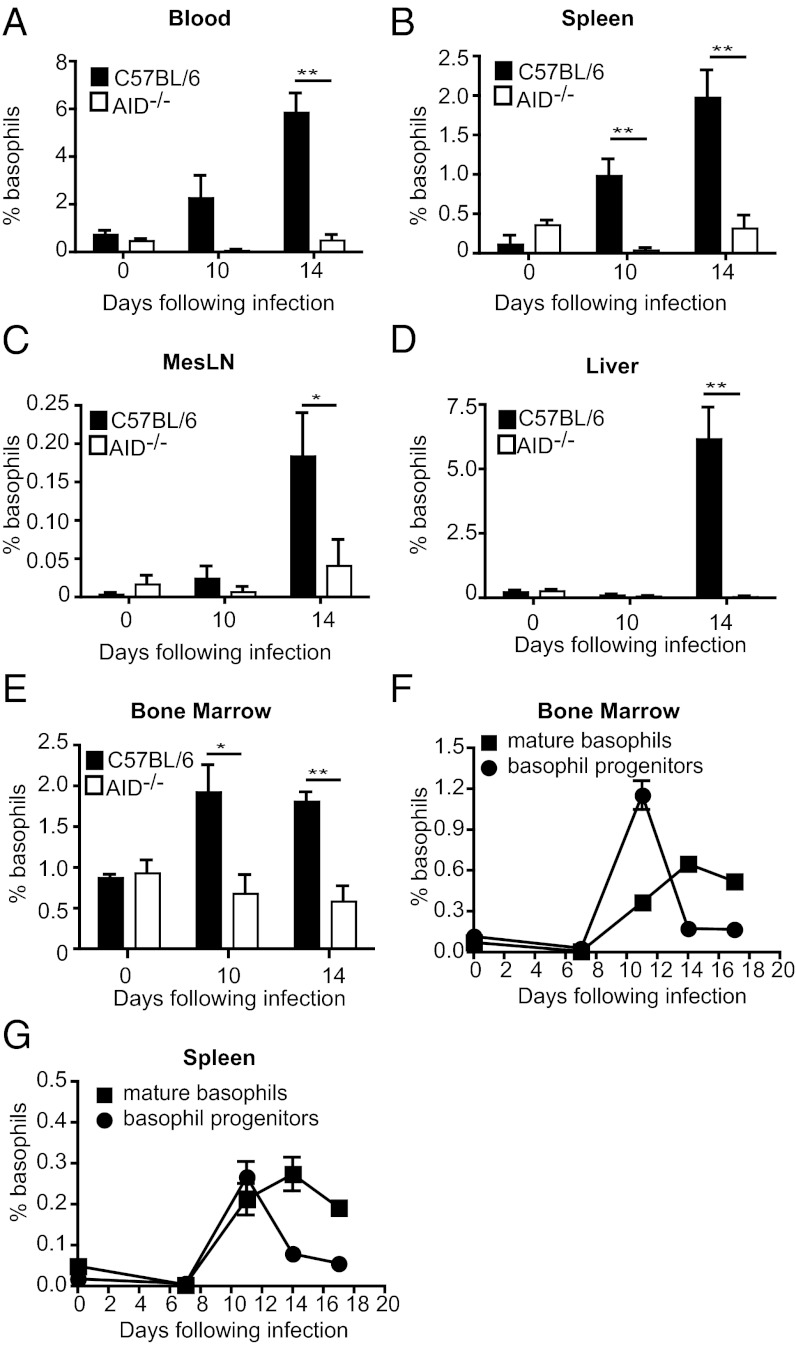

We next set out to determine whether antibodies could promote basophil proliferation and maturation from progenitor cells or survival within the peripheral tissues. A kinetic analysis of various tissues from H. polygyrus bakeri-infected mice revealed an increased percentage of basophils in the blood, spleen, mesenteric lymph node (MesLN), liver, and bone marrow of C57BL/6, but not AID−/− mice by day 14 postinfection (Fig. 2 A–E). Interestingly, basophil numbers increased within the bone marrow (Fig. 2E) and, to a lesser extent, in the spleen and blood of C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2 A and B) by day 10 postinfection, indicating that these organs may represent sites where basophil proliferation and maturation is occurring. We therefore analyzed the relative proportion of basophil progenitors versus mature basophils in these organs based on their expression of CD34 (Fig. S3). Indeed a peak of basophil progenitors was found in the bone marrow, and to a lesser extent in the spleen, on day 10 postinfection (Fig. 3 F and G). These data support the hypothesis that basophil expansion primarily occurs in the bone marrow, and to some extent within the spleen, and indicate that antibodies likely function to promote expansion and maturation of basophil progenitor cells located at these sites.

Fig. 2.

Basophil expansion and maturation is reduced in all lymphoid and hematopoietic tissues of AID−/− mice. Percentage of basophils in C57BL/6 or AID−/− mice infected with H. polygyrus bakeri was determined for (A) blood, (B) spleen, (C) mesenteric lymph node, (D) liver, and (E) bone marrow by flow cytometry. (F and G) Basophil progenitors and mature basophils in C57BL/6 mice were determined by flow cytometry at various time points following H. polygyrus bakeri infection for (F) bone marrow and (G) spleen. All data are shown as the combined mean ± SEM of individual mice (n = 4–5 mice per group) from one experiment and are representative of two independent experiments.

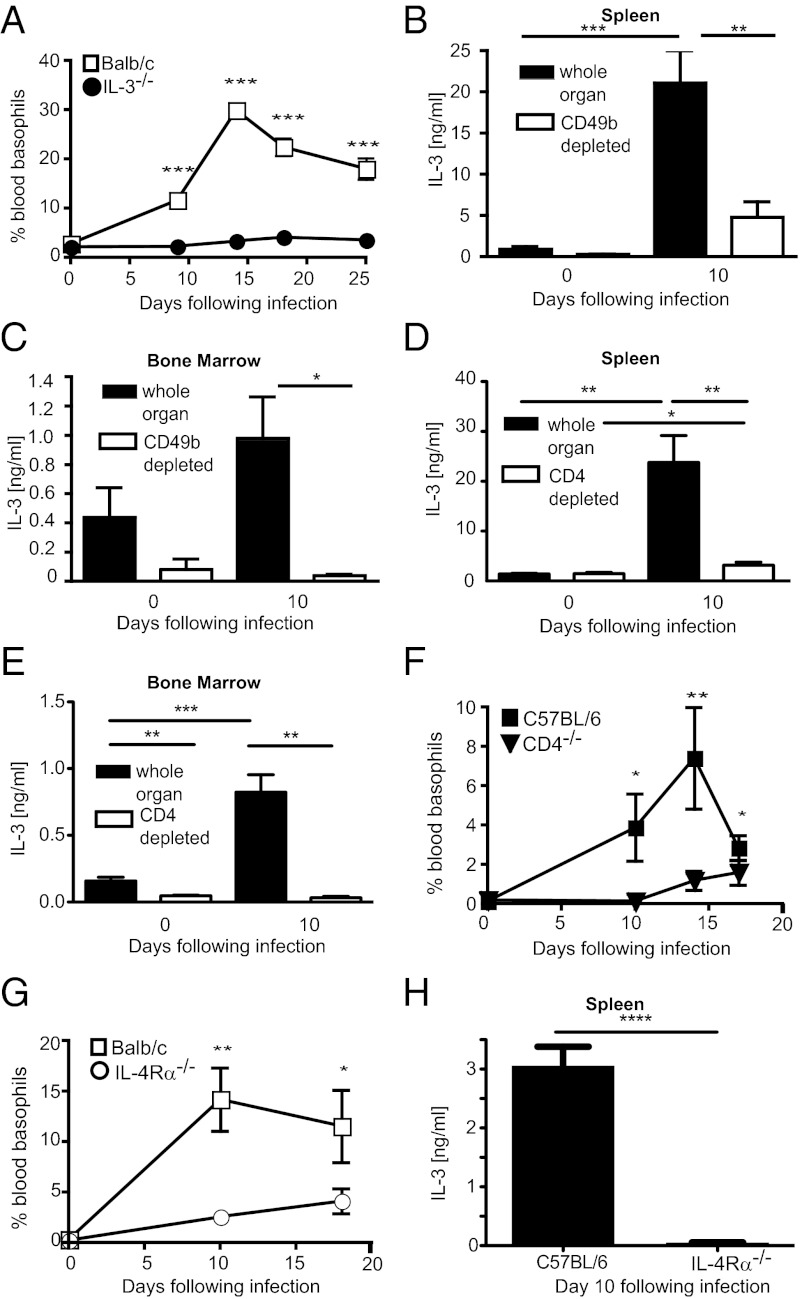

Fig. 3.

H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia is IL-3 dependent. (A) BALB/c or IL-3−/− mice were infected with H. polygyrus bakeri and the percentage of blood basophils was determined by flow cytometry. (B–E) Spleen and bone marrow cells were isolated from naïve or day 10 H. polygyrus bakeri-infected C57BL/6 mice and restimulated in vitro with PMA/ionomycin for 24 h. Levels of IL-3 in supernatant of whole organ culture, CD49b depleted cell fractions (B and C), or CD4 depleted cell fractions (D and E) were quantified by ELISA. (F) C57BL/6 or CD4−/− mice were infected with H. polygyrus bakeri and the percentage of blood basophils was determined by flow cytometry. (G) BALB/c or IL-4Rα−/− BALB/c mice were infected with H. polygyrus bakeri and the percentage of blood basophils was determined by flow cytometry. (H) Spleen cells were isolated from day 10 H. polygyrus bakeri-infected C57BL/6 or IL-4Rα−/− C57BL/6 mice and restimulated in vitro with PMA/ionomycin for 24 h. Levels of IL-3 in supernatant of whole organ cultures were quantified by ELISA. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three to seven animals per group from one experiment and are representative of at least two independent experiments.

H. polygyrus bakeri-Induced Basophil Expansion Requires IL-3.

We have previously shown that H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia occurred independently of TSLP receptor (TSLPR) signaling (22), and others have reported that N. brasiliensis-induced basophilia requires IL-3 (16, 23). Analysis of IL-3−/− animals demonstrated that IL-3 was also necessary for basophil production in response to H. polygyrus bakeri (Fig. 3A), despite normal levels of helminth-induced IgE and IgG1 in these mice (Fig. S4). No increase in circulating IL-3 could be detected by ELISA following infection, indicating that a local source of IL-3 is necessary for basophil expansion in the bone marrow and spleen. We therefore analyzed IL-3 production in cultures of whole spleen or bone marrow following nonspecific restimulation of cells in vitro. As expected, H. polygyrus bakeri infection resulted in enhanced IL-3 production by in vitro restimulated cells from both organs, peaking at day 10 postinfection (Fig. 3 B and C). IL-3 production could be abrogated by prior depletion of CD49b-expressing cells, which include basophils, NK cells, NK T cells, and activated T cells (Fig. 3 B and C). In vitro depletion of CD4+ T cells led to a similar abrogation of IL-3 production in both organs (Fig. 3 D and E) and CD4-deficient mice failed to expand basophils in vivo following H. polygyrus bakeri infection (Fig. 3F). These findings indicated that CD4+ T cells expressing CD49b are the major cellular source of IL-3 present in the spleen and bone marrow following helminth infection. That these cells were CD4+ T cells and not CD4+ NK T cells was determined by depletion of NK1.1+ cells from whole cell cultures, which had no impact on in vitro IL-3 production (Fig. S5). In accordance with the association of basophils with type 2 immunity, both basophil mobilization following helminth infection and in vitro splenic IL-3 production, required signaling via the IL-4Rα chain (Fig. 3 G and H).

Antibodies Bind to Basophils and Promote Basophil Expansion Independently of IL-4Rα Signaling.

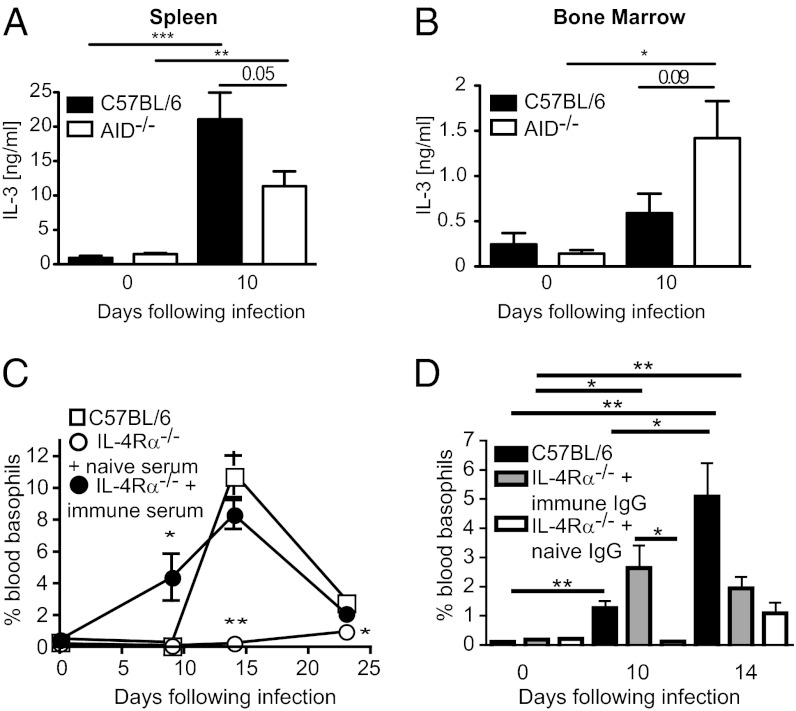

To determine whether antibodies acted to promote basophil expansion by affecting CD4+ T-cell IL-3 production we examined IL-3 levels in in vitro stimulated spleen and bone marrow cell cultures from AID−/− mice. Surprisingly AID deficiency had little impact on IL-3 production in these organs with splenic AID−/− cells making slightly less, but bone marrow AID−/− cells making slightly more, IL-3 than their C57BL/6 counterparts (Fig. 4 A and B). These data indicated that antibodies promote basophil expansion independently of T-cell–derived IL-3. Although we previously showed that CD4+ T cells, and signaling through the IL-4Rα chain, are required for in vitro IL-3 production, they are also required for the production of IgG1 and IgE following primary and secondary infection and worm rejection following secondary infection, with H. polygyrus bakeri (Fig. S6) (18). We therefore determined whether antibody supplementation of IL-4Rα−/− mice could restore basophilia in these mice. Supplementation of immune serum in IL-4Rα−/− mice completely restored H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia (Fig. 4C). Importantly, no soluble IL-3 could be detected in immune serum, indicating that it was the antibody component that was responsible for the observed increase in basophil numbers. We next assessed the ability of purified immune IgG to enhance basophil production. Immune IgG supplementation led to a significant increase of blood basophils by day 10 postinfection in the IL-4Rα−/− mice (Fig. 4D), but declined thereafter probably as a result of the rapid parasite clearance observed in this group.

Fig. 4.

Antibodies promote basophil expansion in IL-4Rα-deficient mice. (A and B) Spleen and bone marrow cells were isolated from naïve or day 10 H. polygyrus bakeri-infected C57BL/6 or AID−/− mice and restimulated in vitro with PMA/ionomycin for 24 h. Levels of IL-3 in supernatant of whole organ cultures were quantified by ELISA. (C) IL-4Rα−/− C57BL/6 or wild-type C57BL/6 mice were infected with H. polygyrus bakeri and additionally injected with 100 μL of naïve or immune serum from C57BL/6 mice every second day from day 0 of infection, and the percentage of basophils in the blood was determined by flow cytometry. (D) Basophil percentages in the blood were determined for IL-4Rα−/− C57BL/6 mice receiving 220 μg naïve or immune IgG every second day from day 0 of infection (the amount of purified IgG was matched to that found in complete immune serum). Data are shown as the combined mean ± SEM of individual mice (n = 3–5 mice per group) from one experiment and are representative of at least two independent experiments.

These data indicated that antibodies promote basophil mobilization even in the absence of T-cell–derived IL-3, despite basophil mobilization being an IL-3–dependent process. IgE stimulation of murine mast cells (24) or human basophils (25) can result in IL-3 production and proliferation in vitro, raising the possibility that antibodies act to elicit autocrine IL-3 production by basophils in vivo following helminth infection. We first determined that either IgE or IgG1 cross-linking could promote IL-3 mRNA expression by bone-marrow–derived murine basophils in vitro (Fig. S7). We then investigated whether a similar process occurred in vivo. As basophils express high levels of IL-3R, we reasoned that ELISA-based detection of IL-3 production by these cells may not be possible, and instead analyzed IL-3 production by intracellular cytokine staining of spleen and bone marrow cells enriched for CD49b and restimulated with phorbol–12-myristat–13-acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin in the presence of monensin to prevent IL-3 export from the endoplasmic reticulum. No increase in IL-3 production by bone marrow cells could be observed using this approach; however, a small population of IL-3+ cells was observed in the spleen and the majority of these were CD4+CD49+NK1.1− T cells (Fig. S8). By contrast, no IL-3 production by basophils was observed (Fig. S8). Thus, IL-3 production by basophils is either below the level of detection or does not occur, indicating that alternative pathways may initiate antibody-mediated basophilia.

IgG1 and IgE Isotypes Promote Basophil Expansion.

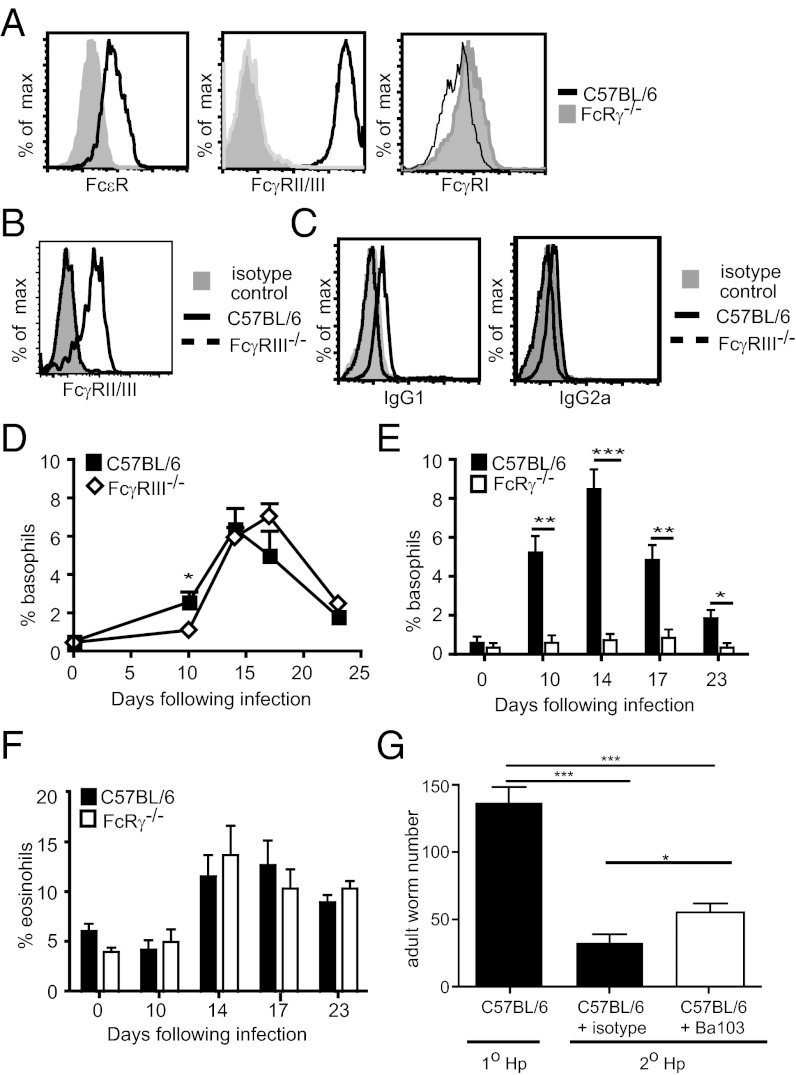

To determine which antibody isotypes might contribute to basophil expansion, we examined in vitro IL-3 expanded bone-marrow–derived basophils, for Fc receptor expression. Flow cytometric analysis revealed expression of the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcεR1), but an absence of the high-affinity IgG receptor (FcγRI) (Fig. 5A). A strongly positive staining was also noted for the 2.4G2 mAb that exhibits cross-reactivity for the low-affinity IgG receptors FcγRII and FcγRIII (Fig. 5A). An absence of the 2.4G2 staining in blood basophils from helminth-infected FcγRIII−/− mice indicated that these cells only express the FcγRIII (Fig. 5B). To identify the IgG subclasses bound by FcγRIII, we investigated IgG binding in blood basophils from infected C57BL/6 and FcγRIII−/− mice. Basophils from C57BL/6, but not FcγRIII−/− mice exhibited significant binding to IgG1 and low-level binding of IgG2a (Fig. 5C). No binding to IgG2b could be determined, indicating that basophils do not express FcγRIV. We next investigated the impact of FcR binding on H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia in vivo. We first examined basophilia in helminth-infected FcγRIII−/− mice. An absence of FcγRIII resulted in reduced early basophilia (Fig. 5D), but did not significantly impact on the peak of the response. To determine the possible contribution of IgE to the response, we therefore investigated helminth-induced basophilia in FcRγ−/− mice that lack expression of FcγRI, FcγRIV, FcγRIII, and FcεR1 antibody receptors (26). Similar to AID−/− mice, FcRγ−/− mice exhibited a complete abrogation of helminth-induced basophil expansion (Fig. 5E), but showed comparable eosinophil production to wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5F). Together these data indicate an important role for both IgG1 and IgE in selectively promoting basophil expansion.

Fig. 5.

Antibody-mediated basophil expansion requires IgG1 and IgE binding to Fc receptors. (A) Bone-marrow–derived basophils from C57BL/6 or FcRγ−/− mice were stained for FcεR, FcγRII/III, or FcγR1. (B and C) Basophils were identified in the blood of C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 FcgRIII−/− mice infected 15 d previously with H. polygyrus bakeri and their surface expression of (B) FcγRII/III or (C) IgG1 and IgG2a were determined by flow cytometry. (D) Blood basophils in C57BL/6 or FcγRIII−/− mice were quantified by flow cytometry following H. polygyrus bakeri infection. Percentage of (E) basophils or (F) eosinophils was determined in blood smears of H. polygyrus bakeri-infected C57BL/6 or FcRγ−/− mice. (G) C57BL/6 mice were subjected to primary or secondary infection with H. polygyrus bakeri. One group of secondary infected mice additionally received 10 μg of the basophil-depleting antibody Ba103 or an isotype control on days −2, 0, 5, and 8 postinfection. Mice were killed on day 12 postinfection and numbers of adult worms were determined by counting using a dissecting microscope. All data are representative of least two independent experiments.

Basophils Contribute to Acquired Immunity Against H. polygyrus bakeri.

Antibody-activated basophils are a potent source of IL-4 (27), which could potentially contribute to the development of an optimal type 2 immune response. Helminth-induced basophilia was not required for the development of normal Th2 cell response following primary H. polygyrus bakeri infection as specific restimulation of cells from the draining mesenteric lymph nodes with helminth antigens revealed similar IL-4, IL-3, and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells from C57BL/6 or basopenic AID−/− mice (Fig. S9). By contrast, basophils were found to partially contribute to protective immunity against H. polygyrus bakeri, as basophil depletion following secondary infection using the CD200R3-specific monoclonal antibody (Ba103) resulted in a small but significant increase in the number of adult worms recovered from the intestine (Fig. 5G). Despite their impact on worm survival, basophils did not contribute to IgE production during secondary helminth infection, as total IgE levels were similar in isotype or Ba103-treated C57BL/6 mice (Fig. S9).

Discussion

Our data reveal a unique role for isotype-switched antibodies in enhancing basophil expansion following helminth infection. We further show that this function requires the FcRγ chain and is most likely a result of IgE production. The FcRγ chain has been previously shown to associate with the IL-3 receptor and to mediate signals required for IL-3–induced IL-4 production by basophils (28). However, this chain was not required for IL-3–induced basophil expansion (28), indicating that its role in antibody-mediated signaling, rather than its association with the IL-3 receptor, accounts for the absence of helminth-induced basophila in our experiments. The effect of isotype-switched antibodies was confined to basophils and did not reflect an effect on Th2 priming as helminth-induced Th2 induction and eosinophilia were normal in the basopenic AID or FcRγ chain-deficient mice.

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-3 production by T cells alone is sufficient for N. brasiliensis-induced basophilia (23). In keeping with this finding, we observed that an absence of antibody did not impact on basophilia during N. brasiliensis infection, but that addition of immune antibodies could enhance basophil expansion. Interestingly, the basophilia observed in N. brasiliensis-infected mice was notably lower than that observed following H. polygyrus bakeri infection. This may indicate that CD4+ T-cell–derived IL-3 can function to promote basophilia at low levels, but that further stimulation in the form of antibodies is able to significantly enhance basophil mobilization. As H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia could occur in the absence of T-cell–derived IL-3, it is not clear whether antibodies function by eliciting autocrine IL-3 production by basophils or by delivering an independent survival signal that can compensate for a lack of T-cell–derived IL-3. The accelerated appearance of basophils in immune serum/IgG supplemented IL4Rα−/− mice, and the delayed basophilia in JHT-deficient mice, both point to a particular role of antibodies in the rapid basophil mobilization early after infection. Of note, IgE is known to regulate mast cell survival through the suppression of apoptosis, raising the possibility that antibodies may promote basophil mobilization through antiapoptotic effects. Lastly, given the sporadic production of basophils in helminth-infected JHT-deficient mice, we believe it is likely that additional factors, such as parasitic antigens, also contribute to basophil expansion. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that basophil numbers in wild-type mice decline soon after H. polygyrus bakeri leaves the intestinal wall to enter the intestinal lumen, yet antibody levels remain elevated for prolonged periods.

Although our studies indicate that both antigen and antibodies are required to promote H. polygyrus bakeri-induced basophilia, the need for antigen specificity cannot be deduced from the current data. We have previously reported that detection of H. polygyrus bakeri-specific antibodies by ELISA is not possible before day 20 for IgG1, or only after secondary infection for IgE (18). However, in the same study, Western blot analysis revealed the presence of low affinity IgG antibodies in the serum of mice by days 10–13 following primary infection (18), and in the current study we could show specific IgM and the presence of antibody–antigen complexes as early as day 7 postinfection. These data indicate that low-affinity antibodies, present at early time points following H. polygyrus bakeri, but not N. brasiliensis infection may promote basophil expansion. However, it is also possible nonspecific IgE can regulate basophil expansion in a manner similar to that previously reported for mast cell survival (29, 30). In support of this possibility, Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens can elicit IL-4 secretion from basophils following nonspecific interactions with surface bound IgE (31), and Hill et al. (32) recently reported that elevated levels of natural IgE in germ-free mice are responsible for the enhanced baseline levels of basophils observed in these mice.

We have shown that helminth-induced basophilia does not impact on cytokine production by Th2 cells following primary infection with H. polygyrus bakeri. Similar findings have recently been reported for type 2 responses following exposure to S. mansoni eggs (10) and N. brasiliensis larvae (7, 10). By contrast, basophils were shown to contribute to protective immunity following challenge infection with N. brasiliensis (7, 8, 10) or ticks (11). Impediment of tick feeding by basophils in immune mice was further demonstrated to require antibody and Fc receptor binding (11). Our previous work uncovered a unique role for isotype-switched antibodies in mediating worm rejection following secondary infections, but not primary infections, with H. polygyrus bakeri (18). We therefore investigated the contribution of antibody-elicited basophils to acquired immunity against this helminth. In vivo basophil depletion using the Ba103 mAb resulted in a small but significant increase in the number of adult worms recovered from mice following secondary infection, indicating a protective role for these cells. However, it should be noted that the impact of basophil depletion was minor compared with the severely impaired protective immunity previously observed in antibody-deficient mice (18). Thus, other mechanisms of antibody-mediated immunity must additionally contribute to worm rejection.

In summary, we have demonstrated that IgE and IgG1 antibodies function to selectively promote basophil expansion and that this can occur independently of T-cell–derived IL-3. Although antibodies have long been recognized to activate basophil effector function, these data provide unique evidence that they can additionally promote basophil hematopoiesis following helminth infection. As basophils are a potent source of type 2 cytokines and inflammatory mediators, the ability of IgE to promote basophil hematopoiesis may represent a unique pathway in which antibodies and basophils act in concert to amplify the effector phase of Th2 immunity.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Parasites, and Treatments.

C57BL/6, BALB/c, AID−/− (19), FcRγ−/− (26), FcγRIII−/− (33), JHT−/− mice, μMT−/− mice (34), IL-4Rα−/− (35), and IL-3−/− (36) mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) or the Malaghan Institute, New Zealand. All animal experiments were performed according to guidelines set by the Victoria University Animal Ethics Committee (Wellington, New Zealand) or the Office Vétérinaire Fédéral (Canton Vaud, Switzerland). Mice were infected orally with 200 L3 H. polygyrus bakeri or s.c. with 500 live L3 N. brasiliensis. Immune serum was collected from naïve mice or at days 13–20 post secondary infection with H. polygyrus bakeri or N. brasiliensis. IgG was purified from tertiary-infected or naïve C57BL/6 mice using Sepharose G beads. For basophil depletion after challenge infection, 10 ug neutralizing anti-CD200R3 antibody (Ba103) or a rat IgG2b isotype control antibody (LTF-2) (Bioxcell) was injected via the i.p. route on days −2, 0, 5, and 8 of secondary infection. Depletion efficiency was calculated for blood basophils at days 5, 9, and 12 postinfection and determined to be between 93 and 98% in all experiments and at all time points. Worm burdens were determined by counting of intestinal worms using a dissecting microscope.

Analysis of Helminth-Induced IL-3 Production.

Cell suspensions from bone marrow or spleen were incubated with PMA/ionomycin for 24 h, and IL-3 levels in the supernatant were determined by ELISA using the BioLegend antibodies MP2-8F8 and MP2-43D11, according to manufacturer instructions. CD49b+ cells or CD4+ cells were depleted by magnetic cell sorting (MACS) (Milteny Biotech).

Analysis of Eosinophils and Basophils.

Differential cell counts were made on Diff Quik (Dade Behring)-stained blood smears. Flow cytometry cell analysis was performed using anti–IgE-FITC (r35-72; BD Pharmingen) or FcεR-FITC (Mar-1; eBioscience), CD49b-PE (HMα2; BD Pharmingen), and anti–Thy1.2-APC (53-2.1; BD Pharmingen). Basophil progenitors were identified by flow cytometry using streptavidin APC-Cy7 (CD19 biotin, CD3 biotin, NK1.1 biotin, GR-1 biotin), CD34 FITC (eBioscience), Sca-1 PE-Cy7, c-kit Pacific blue, and IgE PE (BioLegend).

For in vitro generation of basophils, bone marrow cells were grown in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS and 5% (vol/vol) IL-3 (supernatant of 63×) for a period of 12 d with floating cells harvested and added to fresh medium every 2–3 d. At the end of the culture period, FcR expression was determined by FcεR-FITC (Mar-1; eBioscience) anti–FcγRII/III-FITC (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen), or an istoype control, rat antimouse FcγRI (290322; R&D Systems) and goat antirat IgG2a-FITC (Southern Biotech). For analysis of IgG binding to basophils, antimouse IgG1-FITC [goat antimouse F(ab′)2], IgG2a-FITC, or an isotype control (all Southern Biotech) was used.

Statistical Analysis.

For all data, significant differences were determined between gene-deficient or treatment groups and wild-type mice by a one-tailed Student t test (for parametric data) or a Mann–Whitney u test (for nonparametric data) with a confidence interval of 95%. Significant P values are shown at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_133104), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the Marjorie Barclay Trust. N.L.H. is supported by the Swiss Vaccine Research Institute and T.H. was supported by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Research Grant TH-1507-3. J.P.H. and R.M.M. were supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant. G.L.G. was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Marjorie Barclay Trust.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1117584109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ohnmacht C, Voehringer D. Basophil effector function and homeostasis during helminth infection. Blood. 2009;113:2816–2825. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-154773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Min B. Basophils: What they ‘can do’ versus what they ‘actually do’. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1333–1339. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammad H, et al. Inflammatory dendritic cells—not basophils—are necessary and sufficient for induction of Th2 immunity to inhaled house dust mite allergen. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2097–2111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang H, et al. The T helper type 2 response to cysteine proteases requires dendritic cell-basophil cooperation via ROS-mediated signaling. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:608–617. doi: 10.1038/ni.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsujimura Y, et al. Basophils play a pivotal role in immunoglobulin-G-mediated but not immunoglobulin-E-mediated systemic anaphylaxis. Immunity. 2008;28:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukai K, et al. Basophils play a critical role in the development of IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation independently of T cells and mast cells. Immunity. 2005;23:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnmacht C, et al. Basophils orchestrate chronic allergic dermatitis and protective immunity against helminths. Immunity. 2010;33:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnmacht C, Voehringer D. Basophils protect against reinfection with hookworms independently of mast cells and memory Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:344–350. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrigoue JG, et al. MHC class II-dependent basophil-CD4+ T cell interactions promote T(H)2 cytokine-dependent immunity. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:697–705. doi: 10.1038/ni.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan BM, et al. Genetic analysis of basophil function in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:527–535. doi: 10.1038/ni.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wada T, et al. Selective ablation of basophils in mice reveals their nonredundant role in acquired immunity against ticks. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2867–2875. doi: 10.1172/JCI42680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lantz CS, et al. IL-3 is required for increases in blood basophils in nematode infection in mice and can enhance IgE-dependent IL-4 production by basophils in vitro. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1134–1142. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Gros G, et al. IL-3 promotes production of IL-4 by splenic non-B, non-T cells in response to Fc receptor cross-linkage. J Immunol. 1990;145:2500–2506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rottem M, Goff JP, Albert JP, Metcalfe DD. The effects of stem cell factor on the ultrastructure of Fc epsilon RI+ cells developing in IL-3-dependent murine bone marrow-derived cell cultures. J Immunol. 1993;151:4950–4963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohmori K, et al. IL-3 induces basophil expansion in vivo by directing granulocyte-monocyte progenitors to differentiate into basophil lineage-restricted progenitors in the bone marrow and by increasing the number of basophil/mast cell progenitors in the spleen. J Immunol. 2009;182:2835–2841. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lantz CS, et al. Role for interleukin-3 in mast-cell and basophil development and in immunity to parasites. Nature. 1998;392:90–93. doi: 10.1038/32190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siracusa MC, et al. TSLP promotes interleukin-3-independent basophil haematopoiesis and type 2 inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nature10329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCoy KD, et al. Polyclonal and specific antibodies mediate protective immunity against enteric helminth infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muramatsu M, et al. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu H, Zou YR, Rajewsky K. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell. 1993;73:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewitson JP, et al. Heligmosomoides polygyrus elicits a dominant nonprotective antibody response directed against restricted glycan and peptide epitopes. J Immunol. 2011;187:4764–4777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Massacand JC, et al. Helminth products bypass the need for TSLP in Th2 immune responses by directly modulating dendritic cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13968–13973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen T, et al. T cell-derived IL-3 plays key role in parasite infection-induced basophil production but is dispensable for in vivo basophil survival. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1201–1209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sly LM, et al. IgE-induced mast cell survival requires the prolonged generation of reactive oxygen species. J Immunol. 2008;181:3850–3860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroeder JT, Chichester KL, Bieneman AP. Human basophils secrete IL-3: Evidence of autocrine priming for phenotypic and functional responses in allergic disease. J Immunol. 2009;182:2432–2438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takai T, Li M, Sylvestre D, Clynes R, Ravetch JV. FcR gamma chain deletion results in pleiotrophic effector cell defects. Cell. 1994;76:519–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Panhuys N, et al. Basophils are the major producers of IL-4 during primary helminth infection. J Immunol. 2011;186:2719–2728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hida S, et al. Fc receptor gamma-chain, a constitutive component of the IL-3 receptor, is required for IL-3-induced IL-4 production in basophils. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:214–222. doi: 10.1038/ni.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asai K, et al. Regulation of mast cell survival by IgE. Immunity. 2001;14:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalesnikoff J, et al. Monomeric IgE stimulates signaling pathways in mast cells that lead to cytokine production and cell survival. Immunity. 2001;14:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schramm G, et al. Cutting edge: IPSE/alpha-1, a glycoprotein from Schistosoma mansoni eggs, induces IgE-dependent, antigen-independent IL-4 production by murine basophils in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:6023–6027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill DA, et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat Med. 2012;18:538–546. doi: 10.1038/nm.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hazenbos WL, et al. Impaired IgG-dependent anaphylaxis and Arthus reaction in Fc gamma RIII (CD16) deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;5:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80494-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kühn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohrs M, et al. Differences between IL-4- and IL-4 receptor alpha-deficient mice in chronic leishmaniasis reveal a protective role for IL-13 receptor signaling. J Immunol. 1999;162:7302–7308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mach N, et al. Involvement of interleukin-3 in delayed-type hypersensitivity. Blood. 1998;91:778–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.