Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a central role in regulating immune activation and responses to self. DC maturation is central to the outcome of antigen presentation to T cells. Maturation of DCs is inhibited by physiological levels of 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3] and a related analog, 1α,25(OH)2-16-ene-23-yne-26,27-hexafluoro-19-nor-vitamin D3 (D3 analog). Conditioning of bone marrow cultures with 10−10 M D3 analog resulted in accumulation of immature DCs with reduced IL-12 secretion and without induction of transforming growth factor β1. These DCs retained an immature phenotype after withdrawal of D3 analog and exhibited blunted responses to maturing stimuli (CD40 ligation, macrophage products, or lipopolysaccharide). Resistance to maturation depended on the presence of the 1α,25(OH)2D3 receptor (VDR). In an in vivo model of DC-mediated antigen-specific sensitization, D3 analog-conditioned DCs failed to sensitize and, instead, promoted prolonged survival of subsequent skin grafts expressing the same antigen. To investigate the physiologic significance of 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR-mediated modulation of DC maturity we analyzed DC populations from mice lacking VDR. Compared with wild-type animals, VDR-deficient mice had hypertrophy of subcutaneous lymph nodes and an increase in mature DCs in lymph nodes but not spleen. We conclude that 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR mediates physiologically relevant inhibition of DC maturity that is resistant to maturational stimuli and modulates antigen-specific immune responses in vivo.

The dendritic cell (DC) plays a central role in orchestrating cellular immune responses to self and foreign antigens. A process of “maturation” that occurs after the acquisition of antigen results in up-regulation of MHC/peptide and costimulatory ligands on the surface of DCs and in the secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines. In the mature state the DC is primed to activate T cells in an antigen-specific fashion. DC maturation is not, however, a consequence of antigen acquisition per se. Exposure to substances within the tissue microenvironment regulate DC maturational events. Among the factors that induce DC maturation are components of pathogenic microorganisms, products secreted by parenchymal cells and macrophages, and contact with activated T cells (1–6). Whether the preservation of DCs in an immature state results from the absence of maturational stimuli or is also actively maintained is not known.

We have reported that addition of 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3 (the active form of vitamin D3)] to in vitro cytokine-driven cultures of murine bone marrow results in inhibited DC maturation. An analog of 1α,25(OH)2D3 [1α,25(OH)2-16-ene-23-yne-26,27-hexafluoro-19-nor-vitmain D3, subsequently referred to as D3 analog] exerted similar inhibition at 100-fold lower concentration. The effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and D3 analog were absent in bone marrow cultures from 1α,25(OH)2D3 receptor (VDR)-deficient mice and did not result in attenuation of total DC numbers (7). We demonstrate here that DCs conditioned by D3 analog are resistant to subsequent maturational stimuli and mediate tolerogenic immune responses in vivo. Furthermore, we present evidence that the 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR complex contributes to DC homeostasis in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals and Reagents.

C57BL/6 (B6) mice aged 6–10 weeks were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories. VDR-deficient (VDR KO) and wild-type (VDR WT) control mice on the C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Marie Demay, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (8). VDR KO mice received a diet containing 20% lactose, 2.0% calcium, and 1.25% phosphorous (Research Diets, Madison, WI). Cultures were carried out in DMEM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 5% or 10% FCS. mAbs used were: mouse anti-I-Ab-FITC, rat anti-murine CD40-FITC, biotinylated and FITC-coupled hamster anti-murine CD11c, streptavidin-phycoerythrin, and endotoxin-free anti-murine CD40 (PharMingen). Biotinylated mCTLA-4Ig was kindly provided by Jeffrey Bluestone, University of California, San Francisco. For all surface labeling protocols the absence of nonspecific staining was confirmed by the use of isotype control antibodies: biotinylated and FITC-coupled hamster IgG, biotinylated and FITC-coupled mouse IgG2a, and rat IgG2a-FITC (PharMingen). 1α,25(OH)2D3 (ɛ = 18,200 at 264 nm) and 1,25(OH)2-16-ene-23-yne-26,27-hexafluoro-19-nor-D3 (ɛ = 30,400; 35,400; 23,850 at 243, 251, and 260 nm, respectively), kindly provided by Milan Uskokovic, Hoffman La-Roche, Nutley, NJ, were dissolved in ethanol and stored under nitrogen at −80°C.

In Vitro Generation and Modulation of Murine DCs.

Murine bone marrow cultures were prepared with 10 ng/ml each of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor and IL-4 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) as described (7). D3 analog was added on days 2, 4, and 6 to a final concentration of 10−10 M. For experiments involving the addition of maturing stimuli, DCs were replated on day 6 in fresh cytokine-containing medium for an additional 48 h in 24-well plates with or without anti-CD40 (10 μg/ml), macrophage-conditioned medium (MCM) (12.5–50%), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma) (10–50 ng/ml).

Preparation of MCM.

B6 mice were injected i.p. with 1 ml 3% thioglycollate medium (ICN). Peritoneal cavities were flushed 6 days later with 10 ml of DMEM, and the resulting cells were exposed to 2 μg/ml of LPS for 2 h followed by 1 ml of fresh medium per 106 cells. After 48 h the MCM was used immediately or frozen at −80°C.

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

Flow cytometry was carried out on a FACscan Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed by using cellquest software. Cells were suspended in buffer (PBS/0.1% BSA/0.01% NaN3) containing anti-murine FcR and incubated at 4°C with FITC-, phycoerythrin-, biotin-, or streptavidin-coupled primary and secondary staining reagents.

ELISAs for Murine IL-12 p40 and Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β1.

ELISA kits (optEIA, PharMingen) for the detection of murine IL-12 p40 and TGF-β1 were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transfer of Carboxyfluorescein Diacetate-Succinimidyl Ester (CFSE)-Labeled Splenocytes and Analysis of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes (PBLs).

Erythrocyte-depleted male B6 splenocytes were labeled with CFSE as described (7) and injected i.v. into female or male B6 mice at 3 × 107 cells per animal. Blood was collected at various intervals and analyzed by flow cytometry after erythrocyte lysis.

Skin Grafting.

Skin transplantation was carried out by modification of the “pinch graft” technique (9). Tail skin from male B6 mice was grafted onto the left thorax of female B6 mice. Bandages were removed 7 days later and grafts were monitored daily until the rejection (defined as visible breakdown and ulceration of the grafted skin involving 80% or more of the graft).

Analysis of Spleen and Lymph Node DC Populations.

Analysis of lymphoid organs from age-matched pairs of VDR KO and VDR WT mice was carried out. The pairs, varying between 6 and 12 weeks of age, represented members of a number of litters and were analyzed by the same protocol at separate time points. Six pairs were analyzed in total. Subcutaneous lymph nodes (inguinal and axillary) and spleens from VDR KO and VDR WT mice were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in DMEM containing 3.2 mg/ml collagenase type I and 0.4 mg/ml DNase (Sigma), filtered through 45 μM nylon mesh and washed in cold FACs buffer before resuspension at 2 × 106 cells per ml and staining with relevant mAbs.

Statistical Analysis.

For in vitro experiments three or four identical wells were plated for each condition, and results were expressed as mean ± SD for each condition. Differences between groups were analyzed by two-sided, nonpaired t test with significance assigned to differences of P < 0.05. For experiments involving transfer of labeled splenocytes, the persistence of labeled cells at each time point (%CFSE+ve) was expressed as mean ± SD for each group with analysis by two-sided, nonpaired t test. For analysis of MHC class II and costimulatory ligand levels on DCs from age-matched VDR WT and VDR KO mice, the statistical significance of differences between groups was analyzed by both paired and nonpaired, two-sided t tests.

Results

Conditioning of Bone Marrow Cultures with 10−10 M D3 Analog Results in the Accumulation of Immature-Phenotype DCs.

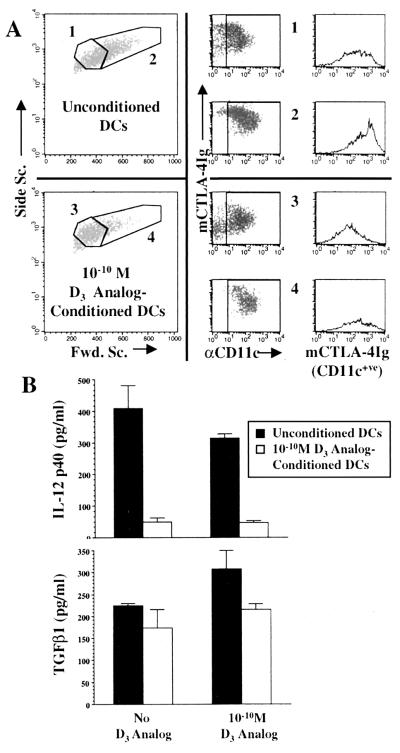

Fig. 1 illustrates cell populations from day-7 bone marrow cultures. In the absence of D3 analog the majority of cells were of higher forward scatter, expressed CD11c, and bound a CD80/CD86 ligand (CTLA-4Ig) at a high level (Fig. 1A). Low forward scatter cells were less plentiful, were also CD11c+ve, and expressed moderate to high levels of CD80/CD86. In D3 analog-containing cultures the predominant cells were low forward scatter with low to intermediate levels of CD80/CD86. High forward scatter cells were less numerous and had lower CD80/CD86 levels compared with cells from untreated cultures. The terms unconditioned DCs and D3 analog-conditioned DCs are subsequently used to describe DCs generated in the absence or presence of D3 analog.

Figure 1.

(A) Cells from day-7 murine bone marrow cultures with and without 10−10 M D3 analog were stained for CD11c (αCD11c) and CD80/CD86 (mCTLA-4Ig). Unconditioned DCs with low forward scatter (no. 1) expressed intermediate to high levels of CD80/CD86 whereas high forward scatter cells (no. 2) expressed high CD80/CD86 levels. D3 analog-conditioned cells of low forward scatter (no. 3) expressed intermediate to low levels of CD80/CD86 whereas high forward scatter cells (4) were less numerous and predominantly expressed intermediate levels of CD80/CD86. (B) Day-6 DCs generated with or without D3 analog were plated in equal numbers for 48 h (days 6–8) in the presence or absence D3 analog, and IL-12p40 and TGF-β1 were measured by ELISA. D3 analog-conditioned DCs secreted markedly less IL-12p40 than unconditioned DCs (Upper, P < 0.05) whereas levels of TGF-β1 did not significantly differ between the two populations (Lower). Addition of D3 analog to unconditioned DCs also resulted in a moderate reduction of IL-12p40 production. Results represent mean ± SD of three or six supernatant samples for each condition. The slight increase in TGF-β1 production by unconditioned DCs upon addition of D3 analog in this experiment was not statistically significant and was not a reproducible finding.

Supernatants from unconditioned and D3 analog-conditioned DCs were analyzed for IL-12 p40 and TGF-β1 (Fig. 1B). Basal secretion of IL-12 p40 by D3 analog-conditioned DCs was significantly less than that of unconditioned DCs regardless of whether or not the analog was present for the final 48 h. A reduction of basal IL-12 p40 secretion by unconditioned DCs also was observed after 48 h of exposure to D3 analog. Although 1α,25(OH)2D3 has been reported to induce TGF-β in some cell lines (10, 11), there were no significant differences in TGF-β1 secretion. Similar results were observed in multiple experiments for IL-12 p40 (three additional experiments) and TGF-β1 (2 additional experiments) secretion by the two populations of DCs.

D3 Analog-Conditioned DCs Are Resistant to Maturational Stimuli.

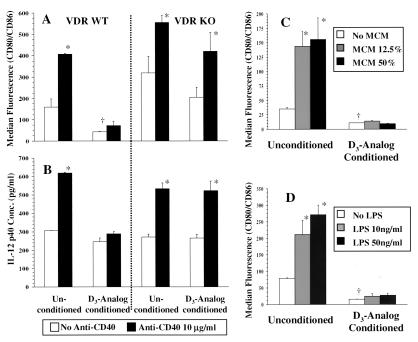

Experiments were performed in which DCs, generated in the presence or absence of D3 analog, were subjected to additional maturing stimuli (Fig. 2). Fig. 2 A and B demonstrates the effects of CD40 cross-linkage on DCs from VDR WT and VDR KO mice. Anti-CD40 was added to unconditioned and D3 analog-conditioned DCs in the absence of D3 analog. Forty-eight hours later DC maturation was assessed by analysis of surface expression of CD80/CD86 (Fig. 2A) and by measurement of IL-12 p40 secretion (Fig. 2B). For unconditioned, wild-type DCs anti-CD40 caused a significant increase in the expression of CD80/CD86 and in IL-12 p40 secretion. D3 analog-conditioned DCs expressed lower levels of CD80/CD86 even upon withdrawal of analog and little up-regulation of CD80/CD86 occurred upon addition of anti-CD40. No significant increase in IL-12 p40 secretion occurred upon CD40 ligation. VDR-deficient DCs responded to CD40 ligation in similar fashion to wild-type DCs but no inhibition was observed after D3 analog conditioning. Fig. 2 C and D illustrates the results of experiments in which unconditioned or D3 analog-conditioned DCs were exposed to variable concentrations of MCM or LPS in the absence of D3 analog. Maturation was assessed by surface expression of CD80/CD86 after MCM and LPS stimulation. Unconditioned DCs exhibited a significant increase in CD80/CD86 expression with exposure to low concentrations of both MCM and LPS. In contrast, D3 analog-conditioned DCs did not display CD80/CD86 up-regulation with either concentration of MCM and LPS. LPS-dependent secretion of IL-12 p40 by D3 analog-conditioned DCs was similarly inhibited (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Day-6 DCs generated with or without D3 analog from VDR WT and VDR KO mice were plated in equal numbers for 48 h in the presence or absence of anti-CD40. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out 48 h later and expressed as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) for CD80/CD86 of CD11c+ve cells (A). ELISA for IL-12 p40 was carried out on culture supernatants 48 h later (B). Both WT and KO unconditioned DCs demonstrated increased CD80/CD86 expression and IL-12 p40 secretion with anti-CD40. D3 analog-conditioned WT DCs failed to significantly up-regulate CD80/CD86 expression and IL-12 p40 secretion after CD40 cross-linkage whereas D3 analog-conditioned KO DCs responded similarly to unconditioned DCs. (C and D) Day-6 unconditioned or D3 analog-conditioned DCs from B6 mice were cultured for 48 h without additional stimulation and with two concentrations each of MCM (C, 12.5% and 50% final volume) or LPS (D, 10 and 50 ng/ml). Results are shown of MFI for CD80/CD86 by CD11c+ve cells. Unconditioned DCs responded to the lower concentration of both stimuli by significantly increasing CD80/CD86 expression. D3 analog-conditioned DCs had lower basal expression of CD80/CD86 that did not significantly increase even with the higher concentrations of the two stimuli. *, P < 0.05 compared with unstimulated cells from the same population; †, P < 0.05 compared with unconditioned DCs.

Multiple experiments were carried out by using CD40 ligation (three additional experiments), MCM (two additional experiments), and LPS stimulation (three additional experiments) with consistent results. For D3 analog-conditioned DCs, addition of D3 analog during stimulation did not consistently result in further inhibition (data not shown). We concluded that differentiation of murine DCs in the presence of D3 analog results in a state of immaturity that is resistant to reversal after withdrawal of the analog and upon exposure to diverse maturing stimuli.

Vitamin D3 Analog-Conditioned DCs Fail to Sensitize Female Hosts to Male Antigen and Facilitate Acceptance of Subsequent Male Skin Grafts.

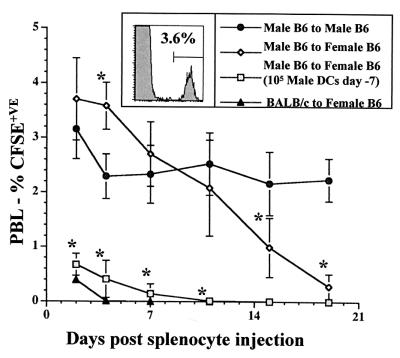

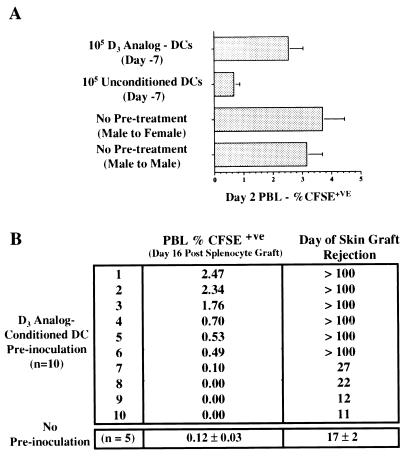

To compare the immunostimulatory properties of unconditioned and D3 analog-conditioned DCs in vivo, we used a model system in which DCs sensitize female mice to minor antigens expressed by syngeneic male cells (Fig. 3). Male B6 splenocytes were labeled with a fluorescent dye and inoculated into male or female B6 mice (12). Flow cytometric analysis of PBLs allowed for quantification of the labeled cells. Sequential analysis revealed that male cells were eliminated by females within 19 days after inoculation but were retained at a constant level by males. Inoculation of female mice with as few as 105 male DCs 7 days before grafting resulted in accelerated elimination with most of the cells cleared by day 2. We tested whether D3 analog-conditioned male B6 DCs also would presensitize female B6 mice (Fig. 4A). Groups of five females were pretreated with 105 unconditioned or D3 analog-conditioned male DCs and grafted with male cells 7 days later. Control groups consisted of naïve females and males. Two days after splenocyte transfer, PBL analysis demonstrated a significant clearance in animals pretreated with unconditioned male DCs but not in those pretreated with D3 analog-conditioned DCs.

Figure 3.

One group of five male B6 mice and two groups of five female B6 mice were inoculated with CFSE-labeled male B6 splenocytes. An additional group of female B6 mice received 3 × 107 CFSE-labeled splenocytes from BALB/c mice. Persistence of labeled cells was determined by sequential flow cytometric analysis of PBLs and expressed as % total cells (Inset). The male recipients and one group of female recipients of male cells received no pretreatment. A second group of female recipients of male cells received 105 unconditioned male B6 DCs i.v. 7 days before splenocyte inoculation. Recipients of BALB/c cells received no pretreatment. Although male recipients retained a constant proportion of labeled cells over a 19-day period the female recipients eliminated the labeled cells between days 7 and 19. Pretreatment with unconditioned male DCs resulted accelerated clearance of male cells, closely resembling the elimination of BALB/c cells. *, P < 0.05 compared with male to male group.

Figure 4.

(A) A group of five male B6 and three groups of five female B6 mice were inoculated with CFSE-labeled male B6 splenocytes. Two days later grafted cells were quantified. Results are expressed as mean ± SD for each group. Male and female recipients that had received no pretreatment had 3.15 ± 0.54% and 3.70 ± 0.75% CFSE+ve cells, respectively (P = 0.2). Females inoculated 7 days previously with 105 unconditioned male B6 DCs had 0.67 ± 0.20% CFSE+ve cells (P = 0.0002 compared with male to male group). Females preinoculated with 105 D3 analog-conditioned DCs had 2.54 ± 0.50% CFSE+ve cells (P = 0.1 compared with male to male group). (B) Ten female B6 mice received 105 D3 analog-conditioned male B6 DCs followed 7 days later by CFSE-labeled male B6 splenocytes. A control group of five female B6 mice received labeled splenocytes without DC preinoculation. The percent of CFSE+ve PBLs 16 days later was determined in each animal (Center). Six of 10 animals preinoculated with D3 analog-conditioned DCs had levels of labeled cells greater than the control group. Seven days later all animals were grafted with male B6 skin and time to graft rejection was determined (Right). The control group rejected male skin grafts between 15 and 19 days posttransplant. Six of 10 DC-treated animals retained skin grafts indefinitely (>100 days) whereas the remaining four rejected grafts between 11 and 27 days posttransplant. Indefinite skin graft survival correlated with prolonged retention of male splenocytes in the group preinoculated with D3 analog-conditioned DCs.

In a subsequent experiment (Fig. 4B), 10 females were preinoculated with D3 analog-conditioned male DCs and the persistence of male splenocyte grafts was determined up to the time of elimination by a naïve control group. At this time point (day 16) 60% of the pretreated group retained male cells, suggesting not only a failure to sensitize, but an attenuation of the response. The animals then were grafted with B6 male skin. The control group uniformly rejected male skin at a mean of 17 days. Among the group initially pretreated with D3 analog-conditioned male DCs, however, indefinite male skin graft survival (>100 days) was observed in six of 10 animals. Prolonged skin graft survival correlated with prolonged retention of male splenocytes. Pretreatment of female animals with unconditioned male DCs results in accelerated rejection of subsequent male skin grafts (data not shown).

Absence of Vitamin D Receptor Results in Increased Maturity of Lymph Node DCs in Vivo.

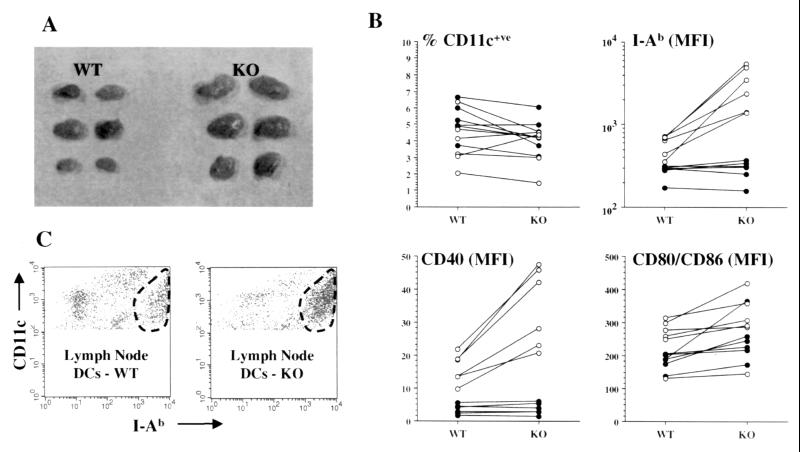

Our observations on the effects of D3 analog on in vitro-derived DCs suggested a physiological role for 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR in DC homeostasis in vivo. We, therefore, analyzed maturation markers in DCs from lymph nodes and spleens of age-matched pairs of VDR WT and VDR KO mice. We drew six age-matched WT and KO pairs (between 6 and 12 weeks old) from our colony for comparative analysis of lymphoid organs. Each pair was analyzed at a separate time. Subcutaneous lymph nodes of VDR KO animals were invariably larger than those of WT animals (Fig. 5A). Spleen size did not differ between the two groups (data not shown). The results of flow cytometric analysis of subcutaneous lymph nodes and spleens are summarized in Fig. 5B. Although the proportion of cells that were CD11c+ve did not differ significantly between WT and KO animals, the expression by CD11c+ve cells of class II MHC (I-Ab), CD40, and CD80/CD86 was significantly higher in lymph nodes from VDR KO mice by using a paired analysis (P = 0.01, 0.003, 0.03 respectively). When nonpaired analysis was used the differences for MHC class II and CD40 expression remained statistically significant (P = 0.016, and 0.012, respectively) whereas the difference for CD80/CD86 expression did not reach significance (P = 0.33). In contrast, splenic DC expression of class II MHC and CD40 did not differ between the two groups. The increased expression of DC maturational markers was primarily the result of an increase in the proportion of large (high forward scatter), class II MHChi DCs (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Analysis of subcutaneous lymph node and splenic DCs from VDR WT and VDR KO mice between 6 and 12 weeks old. (A) Lymph nodes from KO mice were uniformly larger than those of WT (representative example from one pair of animals). (B) Two-color flow cytometric analysis of lymph node (○) and spleen (●) cells from six separately analyzed WT and KO pairs by using stains for CD11c, class II MHC (I-Ab), CD40, and CD80/CD86. Lines connect values for the WT and KO member of each individual pair. P values by paired and nonpaired analysis for differences between WT and KO animals were: lymph node—%CD11c+ve (P = 0.6 and 0.77), I-Ab MFI (P = 0.01 and 0.016), CD40 MFI (P = 0.003 and 0.012), CD80/CD86 MFI (P = 0.03 and 0.33); spleen—%CD11c+ve (P = 0.05 and 0.18), I-Ab MFI (P = 0.4 and 0.7), CD40 MFI (P = 0.3 and 0.8), CD80/CD86 MFI (P = 0.05 and 0.06). (C) An example is shown of flow cytometric analysis of lymph node cells from a VDR WT and KO pair. Class II MHC (I-Ab) expression by CD11c+ve cells is shown. Within the CD11c+ve cells from both animals populations with low, intermediate, and high expression of I-Ab are present. For the KO animal the I-Ab high cells (encircled) represent the predominant population with relative reductions in the I-Ab low and intermediate cells compared with the WT animal.

Discussion

The influence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on immune function has been the subject of numerous reports (13–22). Direct modulation of T cells and macrophage/monocytes by 1α,25(OH)2D3 has been documented in vitro (13–15). Immunosuppressive effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and related analogs also have been documented in vivo in animal models of immune-mediated disease such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, autoimmune diabetes, and allograft rejection (16–20). More recently, a modulatory effect of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on DC differentiation and maturation also has been identified in both human and murine culture systems (7, 21, 22). These findings raise important questions regarding the therapeutic potential for 1α,25(OH)2D3-conditioned DCs, the physiologic role of 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR in DC homeostasis, and the molecular mechanisms that control DC differentiation and maturation. In this report we have used an analog of 1α,25(OH)2D3 to extend our previous observations and those of others on the inhibitory effects of the 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR pathway on DC maturity. This analog exerts identical VDR-dependent in vitro effects to the parent compound at 100-fold lower concentrations (7).

In contrast to the antiproliferative effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on some cell types (15, 23), generation of DCs from bone marrow is not impaired by 1α,25(OH)2D3 although an attenuated progression of maturation occurs. Importantly, we found that D3 analog-conditioned DCs did not progress to a higher level of maturity upon withdrawal of D3 analog and displayed a strikingly blunted response to maturation signals. This observation is consistent with results reported by Piemonti et al. (22) for human DCs generated in the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 after stimulation with LPS or CD40 ligation. We found, in addition, that exposure to MCM did not result in progression of D3 analog-conditioned DCs to a mature phenotype, further emphasizing that the defect involves multiple pathways and suggesting that 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR mediates a functionally important gene expression profile. The effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and its analog on DC cultures resemble those reported by Woltman et al. (24) for dexamethasone on human DCs. Those authors found, however, that early addition of dexamethasone resulted in blockade of DC generation. IL-10 and cyclosporine also have been found to attenuate DC maturity in vitro but the observed effects are not resistant to maturational stimuli (25, 26). As 1α,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to induce expression of TGF-β in a number of cell lines and TGF-β1 negatively effects DC maturation during in vitro culture (10, 11, 27), our observations might have been explained by induction of TGF-β1. We observed, however, no consistent difference in TGF-β1 secretion by unconditioned or D3 analog-conditioned DCs. The influences of the 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR pathway on DC maturation are, therefore, physiologically distinct and may represent a more robust basis for in vivo immunotherapy than other antigen-presenting cell-modifying agents.

Our results comparing the in vivo-sensitizing properties of unconditioned or D3 analog-conditioned DCs highlight the potential role for DC modulation in the development of immunotherapies. For management of neoplasms and generation of vaccines, the codelivery of antigen with accessory signals that promote DC maturation has yielded promising results (28, 29). In the case of transplant rejection, immature-phenotype DCs have been reported to favor prolonged allograft survival (30, 31). In the experiment shown in Fig. 4B and in additional in vivo experiments (data not shown), prolonged graft survival after preinoculation with D3 analog-conditioned DCs has been a consistent finding but has not been invariable. This variability among experimental animals may reflect the presence of a minor population of mature DCs within D3 analog-conditioned cultures or be the result of a delicate balance between “sensitizing” and “tolerizing” pathways during T cells/immature DC interactions. Studies of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and related analogs to attenuate allograft rejection have demonstrated synergy with agents such as calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, and sirolimus (20). Immunotherapeutic strategies using 1α,25(OH)2D3-conditioned DCs or systemic D3 analogs may, therefore, prove most effective when used with additional DC or T cell modulators. The general observation that “tolerogenic” presentation of alloantigen by DCs within the peripheral lymphoid organs can alter subsequent antigen-specific responses represents one of the most promising indications that permanent engraftment of allogenic or xenogenic tissues may be feasible.

Although in vitro-generated DCs are accepted as a valid system in which to study the functional properties of DCs, it is important to appreciate that culture conditions cannot recapitulate the in vivo physiology of DC populations. We, therefore, sought to obtain direct evidence of a physiological role for 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR in regulating DC function. Our findings of lymph node hypertrophy and an excess of mature-phenotype DCs in the s.c. lymph nodes of VDR KO mice are consistent with a dysregulation of immune homeostasis in these animals. Interestingly, the abnormalities were not present in spleen or in mesenteric lymph nodes (unpublished observation), suggesting that the observation was not secondary to a systemic process such as might result from metabolic or nutritional abnormalities in these animals (8).

An alternative explanation for the localized nature of the immunologic abnormality is a dysregulated presentation of antigens from tissues in which DCs are locally exposed to 1α,25(OH)2D3. A view of immune homeostasis has been proposed whereby immature DCs continuously sample antigen from healthy tissues and “cross-present” it in tolerogenic fashion to T cells (32). At present there is no direct evidence that VDR KO animals have an increased incidence of autoimmune disease. It is possible, however, that the nonimmune features of VDR deficiency mask such manifestations and the generation of mice in which only the immune compartment is unresponsive to 1α,25(OH)2D3 will be necessary to definitively address this issue. A poorly understood feature of the VDR KO phenotype is the development, by 4 months of age, of extensive alopecia (8). The animals used for our immune analysis had minimal to mild alopecia and, thus, the lymph node hypertrophy was not likely to be secondary to advanced skin disease. An alternative possibility is that inhibition of DC maturity by locally generated 1α,25(OH)2D3 in the skin may represent a important element in local immune tolerance. There is evidence to support a role for 1α,25(OH)2D3 in regulating antigen-presenting cells in the skin. Upon exposure to UV light, the skin synthesizes cholecalciferol and UV irradiation of the skin during intradermal antigen exposure can generate antigen-specific tolerance (23, 33, 34). Keratinocytes are, furthermore, capable of generating 1α,25(OH)2D3, suggesting that this compound serves a paracrine function within the skin (15, 23). Finally, topical application of a 1α,25(OH)2D3 analog—calcipotriol—suppresses the T cell-mediated skin disease psoriasis (34).

In conclusion, we have found that the inhibitory effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3/VDR on DC maturation result in a distinct phenotypic state that is not readily reversed by maturational stimuli, is associated with altered antigen-specific immune responses in vivo, and may play an important role in regulating immune homeostasis. We propose that ongoing study the interplay between the “negative” and “positive” regulation of DC maturation in individual tissues may advance our understanding of tissue-specific immune tolerance and permit the design of novel therapeutic approaches to autoimmune disease, neoplasia, and allotransplantation.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of James Londowski, Sharon Heppelmann, and the staff of the Mayo Flow Cytometry Core Facility. This work was supported by the Solomon Papper, MD, Young Investigator Grant of the National Kidney Foundation, Mayo Foundation CR20 and CR75 Awards (to M.D.G.), and National Institutes of Health Grants DK-25409 and AR-27032 (to R.K.).

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- 1α,25(OH)2D3

1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3

- VDR

1α,25(OH)2D3 receptor

- VDR WT

VDR wild type

- VDR KO

VDR-deficient

- MCM

macrophage-conditioned medium

- B6

C57BL/6

- MFI

median fluorescence intensity

- D3 analog

1α,25(OH)2-16-ene-23-yne-26,27-hexafluoro-19-nor-vitamin D3

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate-succinimidyl ester

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocyte

References

- 1.Steinman R M. In: Fundamental Immunology. 4th Ed. Paul W E, editor. New York: Raven; 1999. pp. 547–574. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shortman K, Caux C. Stem Cells. 1997;15:409–419. doi: 10.1002/stem.150409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palucka K, Banchereau J. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:12–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1020558317162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchereau J, Steinman R M. Nature (London) 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallusto F, Lanzaveccia A. J Exp Med. 1999;189:611–614. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallucci S, Lolkema M, Matzinger P. Nat Med. 1999;5:1249–1255. doi: 10.1038/15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin M D, Lutz W H, Phan V A, Bachman L A, McKean D J, Kumar R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:701–708. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y C, Pirro A E, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, Demay M B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9831–9835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billingham R E, Medawar P B. J Exp Biol. 1957;28:385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koli K, Keski-Oja J. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1540–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Craig T A, Lutz W H, Kumar R. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2654–2660. doi: 10.1021/bi981944s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oehen S, Brduscha-Riem K, Oxenius A, Odermatt B. J Immunol Methods. 1997;207:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemire J M, Adams J S, Kermani-Arab V, Bakke A C, Sakai R, Jordan S C. J Immunol. 1985;134:3032–3035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Ambrosio D, Cippitelli M, Cocchiolo M G, Mazzeo D, Di Luca P, Lang R, Sinigaglia F, Panina-Bordignon P. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:252–262. doi: 10.1172/JCI1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones G, Strugnell S A, DeLuca H F. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1193–1231. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathieu C, Laureys J, Sobis H, Vandeputte M, Waer M, Bouillon R. Diabetes. 1992;41:1491–1495. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.11.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemire J M, Archer D C. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1103–1107. doi: 10.1172/JCI115072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantorna M T, Hayes C E, DeLuca H F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7861–7864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hullett D A, Cantorna M T, Radaelli C, Humpal-Winter J, Hayes C E, Sollinger H W, DeLuca H F. Transplantation. 1998;66:824–828. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Etten E, Branisteanu D D, Verstuyf A, Waer M, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Transplantation. 2000;69:1932–1942. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005150-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penna G, Adorini L. J Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piemonti L, Monti P, Sironi M, Fraticelli P, Leone B E, Dal Cin E, Allavena P, Di Carlo V. J Immunol. 2000;164:4443–4451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar R, Craig T. In: Nephrology. Jamison R L, Wilkinson R, editors. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. pp. 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woltman A M, de Fijter J W, Kamerling S W, Paul L C, Daha M R, van Kooten C. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1807–1812. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1807::AID-IMMU1807>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brossart P, Zobywalski A, Grunebach F, Behnke L, Stuhler G, Reichardt V L, Kanz L, Brugger W. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4485–4492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J-I, Ganster R W, Geller D A, Burckart G J, Thomson A W, Lu L. Transplantation. 1999;68:1255–1263. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geissmann F, Revy P, Regnault A, Lepelletier Y, Dy M, Brousse N, Amigorena S, Hermine O, Durandy A. J Immunol. 1999;162:4567–4575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein C, Bueler H, Mulligan R C. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1699–1708. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behboudi S, Chao D, Klenerman P, Austyn J. Immunology. 2000;99:361–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomsen A W, Lu L. Immunol Today. 1999;20:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heath W R, Kurts C, Miller J F, Carbone F R. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1549–1553. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinman R M, Turley S, Mellman I, Inaba K. J Exp Med. 2000;191:411–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz A, Beissert S, Grosse-Heitmeyer K, Gunzer M, Bluestone J A, Grabbe S, Schwarz T. J Immunol. 2000;165:1824–1831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashcroft D M, Po A L, Williams H C, Griffiths C E. Br Med J. 2000;320:963–967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]