Abstract

The plant-specific DNA-dependent RNA polymerase V (Pol V) evolved from Pol II to function in an RNA-directed DNA methylation pathway. Here, we have identified targets of Pol V in Arabidopsis thaliana on a genome-wide scale using ChIP-seq of NRPE1, the largest catalytic subunit of Pol V. We found that Pol V is enriched at promoters and evolutionarily recent transposons. This localization pattern is highly correlated with Pol V-dependent DNA methylation and small RNA accumulation. We also show that genome-wide chromatin association of Pol V is dependent on all members of a putative chromatin-remodeling complex termed DDR. Our study presents the first genome-wide view of Pol V occupancy and sheds light on the mechanistic basis of Pol V localization. Furthermore, these findings suggest a role for Pol V and RNA-directed DNA methylation in genome surveillance and in responding to genome evolution.

De novo DNA methylation in the Arabidopsis genome within all sequence contexts is carried out by the DRM2 DNA methyltransferase via the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway1. In contrast, maintenance of DNA methylation is carried out by different DNA methyltransferase systems for cytosines in each of three different sequence contexts. CG and CHG (where H is either C, T or A) are maintained by the MET1 and CMT3 DNA methyltransferases, respectively, whereas asymmetric CHH-context methylation is mostly maintained via persistent targeting by DRM2 and the RdDM pathway1,2.

All eukaryotes have three DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (Pols I, II and III) that are essential for transcription of the genome3. Plants have two additional polymerases (Pol IV and Pol V) that have evolved from Pol II to act in RdDM wherein small RNAs target de novo DNA methylation to transposons and other sequences in the genome1,3. While Pol IV is required for the genome-wide production of 24 nucleotide small RNAs4, Pol V is thought, based on single-locus studies at several intergenic (IGN) loci, to generate non-coding RNA transcripts that serve as molecular scaffolds for recruiting downstream RdDM components5.

Several RdDM effectors have been shown to interact with Pol V and assist in its function at various stages of action6–11. The Argonaute protein, AGO4, and the putative elongation factor, SPT5L, interact with Pol V but act downstream of Pol V binding to chromatin12–14. In contrast, a previously identified putative chromatin remodeling complex termed DDR is thought to act upstream of Pol V to either regulate Pol V activity or stabilize Pol V association with chromatin9. The DRD1, DMS3, and RDM1 proteins comprise the DDR complex and each was previously shown to be required for the production of Pol V-dependent non-coding RNAs at two IGN regions, IGN5 and MEA-ISR9. DRD1 and DMS3 were also reported to mediate Pol V recruitment at several IGN loci5,15. However, despite these informative studies, the current RdDM model for Pol V function is largely based on the characterization of the few identified Pol V targets, and it remains unknown where Pol V is active in the genome, to what extent RdDM components are required for Pol V localization, and what might distinguish Pol V targets from non-targets. To address these questions, we profiled genome-wide Pol V occupancy by ChIP-seq, in both wild type and mutant plants. We found that Pol V is enriched at gene promoter regions and evolutionary young transposons containing marks of epigenetic silencing, and that genome-wide Pol V localization is dependent on DDR complex components.

RESULTS

Pol V occupancy is correlated with marks of epigenetic gene silencing

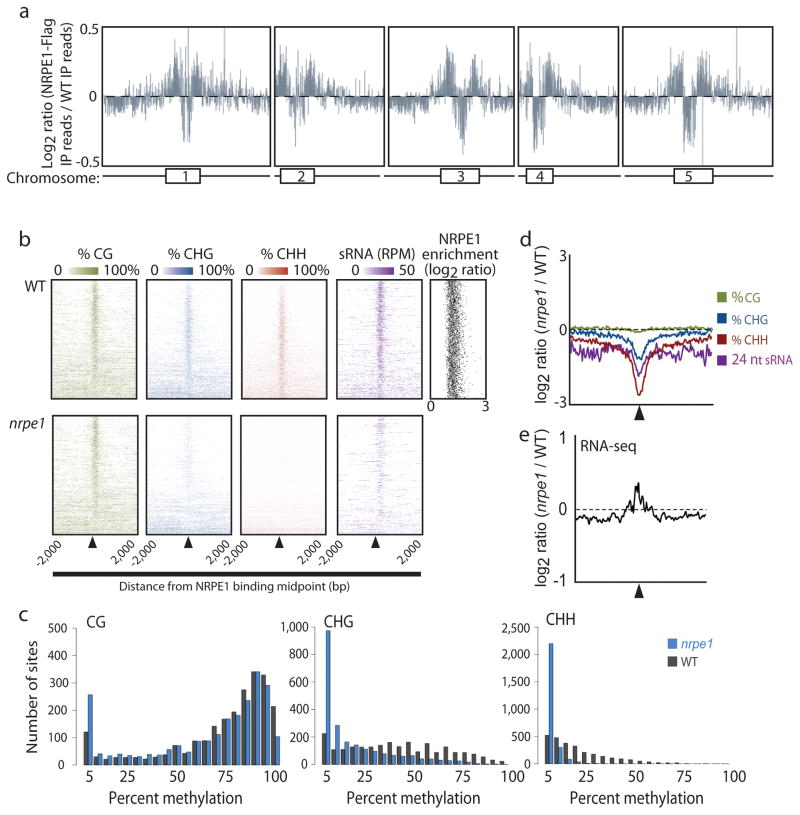

Using chromatin immunoprecipitation in combination with massively parallel sequencing (ChIP-seq), we generated a genome-wide map of the chromatin-association profile of NRPE1, the largest catalytic subunit of Pol V, in Arabidopsis flowers expressing FLAG epitope-tagged NRPE112. At the chromosomal level, NRPE1 was enriched in pericentromeric heterochromatin but not at the central core of centromeric regions (Fig. 1a). In addition we identified 2,600 small NRPE1-enriched regions distributed throughout the chromosomes that were reproducible in two biological replicates (Supplementary Table 1). The vast majority of these defined NRPE1 binding regions (2300 sites or approximately 88%) was shorter than 250 bp (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with a recent finding that Pol V-dependent small RNAs are derived from small, intergenic loci16. To examine the biological significance of these sites, we performed a series of genomic and epigenomic profiling experiments.

Figure 1.

Identification of NRPE1 enriched sites by ChIP-seq and characterization of epigenetic marks at those sites. (a) Chromosomal view of NRPE1-FLAG ChIP-seq reads relative to an untagged wild type (WT) control with a schematic representation of each chromosome shown below. The chromosome numbers represent the approximation of the centromere location with the boxes indicating pericentromeric heterochromatin. (b) Heatmaps showing the % methylation levels in all three sequence contexts as well as 24 nucleotide small RNA abundance (reads per bp per million 21 nt mapping reads) for all NRPE1 sites (+/− 2,000 bp from midpoint) in WT (top) and nrpe1 mutants (bottom) as well as a scatter plot showing the relative NRPE1 enrichment at each site. (c) Distribution of the % methylation of the central 100 base pairs of NRPE1 sites in wild type and nrpe1 mutants. (d) Metaplot (+/− 2,000 base pairs from NRPE1 binding midpoints shown by triangle) showing the relative change of epigenetic marks in shown in (b) for nrpe1 mutants. (e) Metaplot showing the changes of RNA-seq reads in nrpe1 mutants relative to WT.

We first examined the role of NRPE1 in RdDM by performing whole-genome bisulfite sequencing and small RNA sequencing in nrpe1 mutant and wild type (WT) plants. DNA methylation in all three-sequence contexts (CG, CHG and CHH) was highly enriched over NRPE1 binding sites in wild type (Fig. 1b). Notably, CHH, and to a lesser extent, CHG methylation at these sites was NRPE1-dependent (Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Genome-wide small RNA profiling similarly identified a strong enrichment of NRPE1-dependent 24nt RNAs at NRPE1 binding sites (Fig. 1b,d and Supplementary Fig. 2b). We also analyzed a published RNA-seq dataset17 and found, consistent with the silencing function of RdDM, that RNA reads were elevated at NRPE1 binding regions in the nrpe1 mutant relative to wild type (Fig. 1e). Thus Pol V bound sites are highly correlated with marks of epigenetic gene silencing, as well as with the suppression of mRNA in those regions.

The DDR complex is required for global chromatin association of Pol V

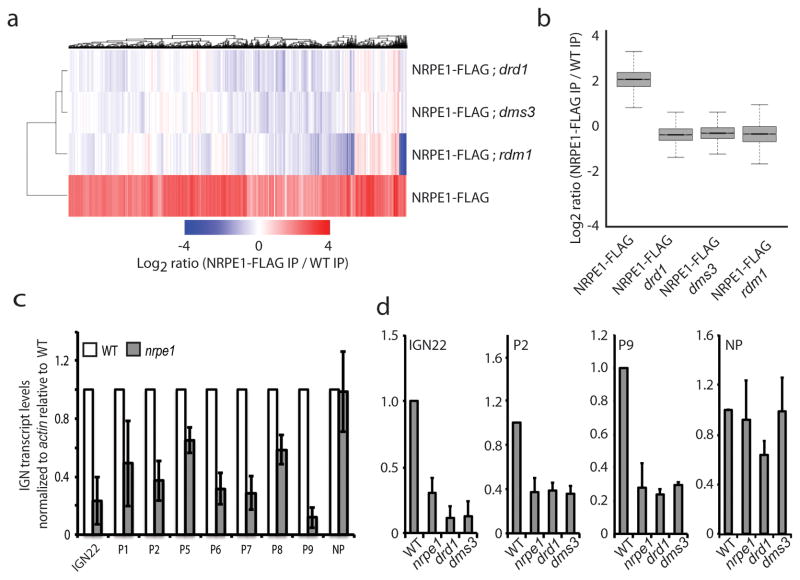

To test the extent to which the DDR complex is required for Pol V localization to chromatin, we crossed the NRPE1-FLAG transgene separately into the drd1, dms3 and rdm1 mutant backgrounds and profiled genome-wide occupancy of NRPE1 in these mutants by ChIP-seq. We found that drd1, dms3 and rdm1 mutations all strongly reduced or eliminated NRPE1 enrichment at all of the defined NRPE1 binding sites (Fig. 2a,b). These results suggest that the previously reported effects of drd1, dms3 and rdm1 mutations on Pol V transcript accumulation are due to effects on Pol V chromatin association. As NRPE1 protein levels were similar between wild type and mutant plants (Supplementary Fig. 3a), these results indicate that all members of the DDR complex act to promote stable, genome-wide Pol V association with its chromatin targets and also further verify that our identified NRPE1 peaks are biologically significant.

Figure 2.

The DDR complex is required for stable Pol V association with chromatin. (a) Heat map of NRPE1 enrichment at sites defined in ChIP-seq experiments in wild type and mutants. The genotype of each library is indicated at the far right side. (b) Boxplot (whiskers extend to +/− 1.5 inter-quartile range (IQR)) of NRPE1 enrichment at sites shown in (a) for various genotypes. (c) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of transcripts originating from NRPE1 enrichment sites. IGN22 is a previously published Pol V target, P2 to P9 are newly identified Pol V binding sites and NP is a non-NRPE1 enrichment region. (d) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of transcripts originating from NRPE1 enrichment sites in nrpe1, drd1 and dms3 mutants. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Pol V site correlate with NRPE1-dependent transcripts

Previous studies have identified several Pol V-dependent non-coding RNA transcripts5,13. To explore whether our ChIP-seq dataset would enable us to identify new Pol V-dependent transcripts, we tested for the presence of potential Pol V-dependent transcripts at our identified NRPE1-enrichment sites. Of seven randomly chosen and validated NRPE1-enrichment sites (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c), all showed the presence of detectable Pol V-dependent transcripts using RT-qPCR (Fig. 2c). In line with our ChIP-seq data, for those RNAs tested (Supplementary Fig. 3d), the Pol V-dependent transcripts were also DDR-dependent (Fig. 2d).

Taken together, our ChIP-seq results, in conjunction with our epigenomic profiling of nrpe1 mutants and the discovery of new Pol V-dependent transcripts, suggest that the enrichment sites in our ChIP-seq dataset represent bona fide Pol V binding sites.

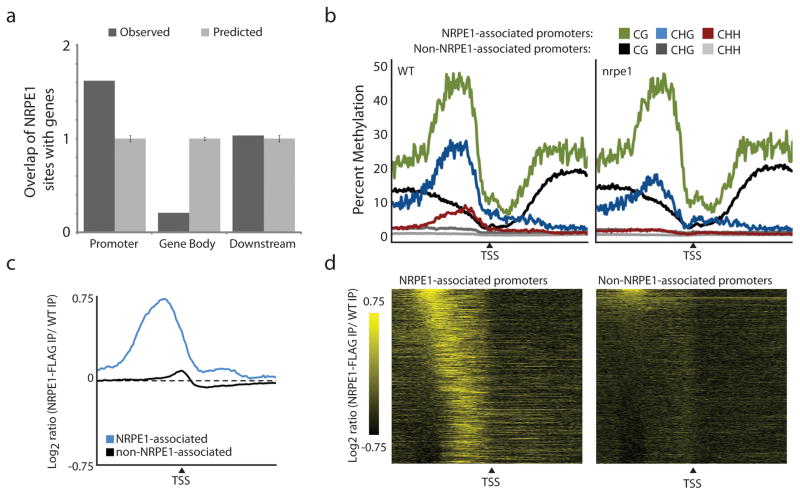

Pol V is enriched at gene promoters containing transposons

Next we sought to identify common features of Pol V targets. Interestingly, yet perhaps consistent with its likely ancestral relationship to Pol II, we found that NRPE1 sites are enriched at gene promoters, which we defined as sequences up to 1kb upstream of a putative transcription start site (Fig. 3a). This observation was further supported by analysis of previously published histone modification profiles18, in which we found that NRPE1 sites are flanked by H3K4 methylation chromatin marks that are found near promoter and genic regions (Supplementary Fig. 4a)18. Promoters overlapping NRPE1 sites, which we referred to as “NRPE1-associated”, are intrinsically different from non-NRPE1-associated promoters in that they contain much higher levels of DNA methylation and 24-nucleotide small RNAs (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Interestingly, we found that even at promoters classified by our analysis as “non-NRPE1-associated” there was a small enrichment of NRPE1 (Fig. 3c,d), consistent with the idea that gene promoters may recruit Pol V in a weak and/or transient manner.

Figure 3.

NRPE1 is enriched at gene promoters. (a) Relative enrichment of the observed overlap between NRPE1 sites and gene features compared to the average overlap of 10,000 genome-shuffled experiments. (b) Metaplots for WT and nrpe1 genomes of DNA methylation for each cytosine context at NRPE1-associated promoters and non-NRPE1-associated promoters. (c–d) Metaplots (c) and heatmaps (d) of ChIP-seq reads at NRPE1-associated promoters versus non-NRPE1-associated promoters. For each panel black triangles denote the transcriptional start site (TSS) with plots extending + or − 2,000 bp upstream and downstream.

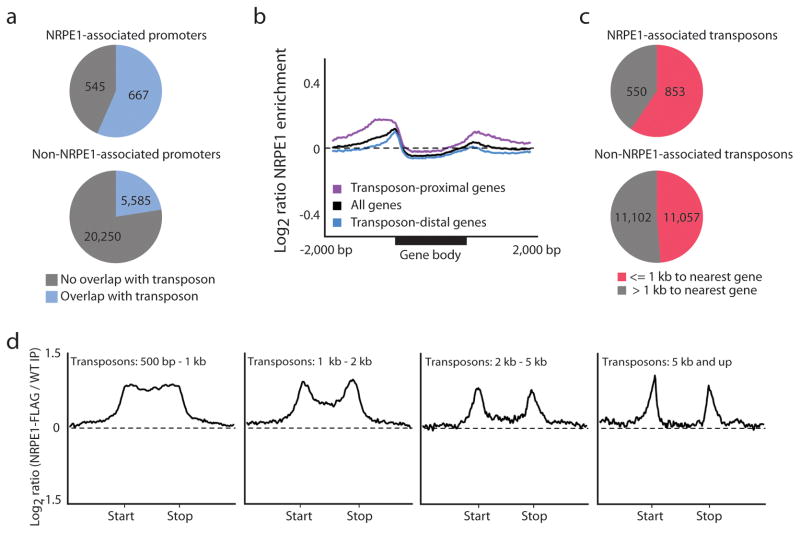

The epigenetic profile of NRPE1-associated promoters can be at least partially attributed to the fact that 55% of NRPE1-associated promoters overlapped with transposons (Fig. 4a), with transposon-proximal genes in general showing higher NRPE1 enrichment at their promoters than genes far from transposons (Fig. 4b). As expected from the presumed function of the RdDM pathway, a large number of the NRPE1 peaks map to annotated transposons (Fig 4c). Further supporting the notion that Pol V might have an inherent affinity for promoters, we found that at NRPE1 associated transposons the profile of NRPE1 binding showed a clear enrichment at transposon edges (Fig. 4d), which are known to contain autonomous transposon promoter elements19,20. Similar to our observations at NRPE1-associated promoters (Fig. 3b), the sub-set of transposons that is NRPE1-associated is significantly enriched for transposons within 1kb of a protein-coding gene (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 5a,b) and these transposons were more heavily methylated and targeted by 24nt small RNAs than non-NRPE1-associated transposons (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d). Thus, our observation of a majority of NRPE1 sites (~54%) overlapping with transposons or transposon fragments within gene promoters supports prevailing models of RdDM wherein repetitive elements such as transposons are common targets, but also suggests that gene promoters, especially promoters with nearby transposons, are frequent targets of Pol V.

Figure 4.

NRPE1 is enriched at the intersection of promoters and transposons. (a) NRPE1-associated promoters are enriched for promoters overlapping with transposons (P<2.2e-16, Fisher’s Exact Test). (b) Metaplot showing NRPE1 enrichment at transposon-proximal (within 1 kb) and -distal (>1 kb) protein coding genes for ± 2,000 bp upstream and downstream and over the gene body (shown in % coverage of gene 5′ to 3′). (c) NRPE1-associated transposons (those overlapping with an NRPE1 site) are enriched for gene-proximal transposons (P<2.2e-16, Fisher’s Exact Test). (d) Metplots of NRPE1 enrichment at NRPE1-associated transposons organized by size class.

Loss of Pol V affects the transcription of Pol V-proximal genes

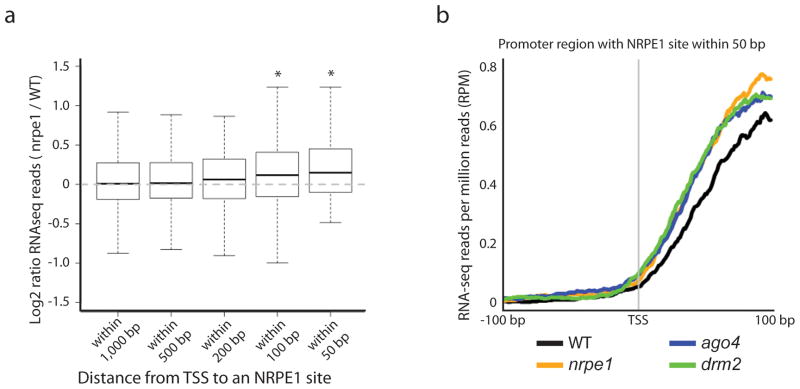

Given the association of Pol V with promoters, we sought to determine whether or not Pol V affects the transcription of endogenous protein coding genes. We examined mRNA expression changes in nrpe1 relative to wild type plants for genes near NRPE1 sites. Indeed, we did observe a significant increase in mRNA expression at genes close to NRPE1 sites as compared to genes not close to NRPE1 sites. In particular, the nearer the NRPE1 site is to the predicted transcriptional start site (TSS), the larger the increase in expression (Fig. 5a). Thus, in the absence of Pol V function, genes near Pol V targets are upregulated. To test whether the up-regulation is due to the production of alternative upstream transcripts that are derepressed in nrpe1 mutant plants, or whether the up-regulation is mainly restricted to the protein coding gene transcripts, we mapped the RNA-seq reads relative to the transcriptional start sites. We found that the extra RNA-seq reads in nrpe1 mutant plants mapped almost exclusively downstream of the TSS, suggesting that loss of Pol V causes up-regulation of the main Pol II protein coding gene transcripts (Fig. 5b). One possibility is that the up-regulation of genes in nrpe1 mutant plants is due to the loss of Pol V transcripts, which otherwise interfere with the transcription of the Pol II promoter. Alternatively, the proximity of an NRPE1 site to a gene might make it more likely that RdDM will dampen the activity of the protein coding gene promoter. To distinguish between these hypotheses, we analyzed RNA-seq data from two additional RdDM mutants, drm2 and ago4, that act downstream of Pol V action 5,13,15. We observed a very similar pattern of gene up-regulation at genes near the NRPE1 sites in these other RdDM mutants (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 4c,d), suggesting that loss of RdDM in general, rather than loss of Pol V specifically, is causing up-regulation of normal Pol II initiation.

Figure 5.

Loss of NRPE1 causes changes in protein coding gene expression. (a) Boxplots (whiskers extend +/−1.5 IQR) of log2 ratios of normalized RNA-seq read counts for nrpe1 mutants over those for wild type plants for protein coding genes with an NRPE1 site in their promoter. Each boxplot represents a subclass of those genes based on the distance between the TSS and the NRPE1 site. * indicates P<0.05 (Mann-Whitney Test). (b) Metaplot showing the normalized RNA-seq reads for different RdDM mutants at and around the TSS of protein coding genes with an NRPE1 site within 50 bp upstream of the TSS.

Pol V is enriched at evolutionarily recent transposons

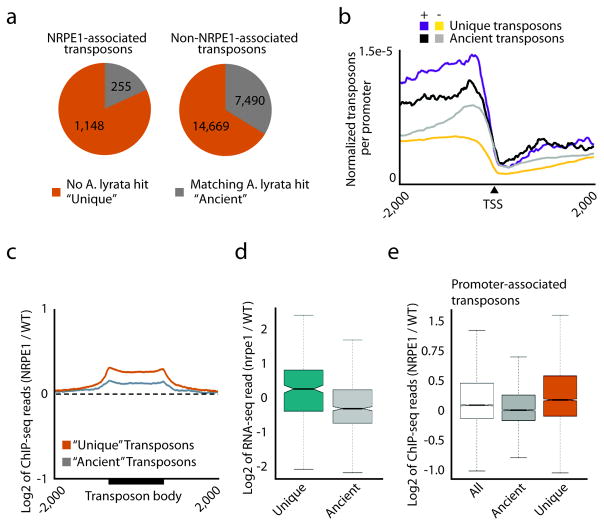

Because Pol V only targets a subset of transposons in the genome (Fig. 4c), we sought to determine if these transposons have any commonalities. In A. thaliana, gene-proximal transposons are relatively young compared to gene-distal transposons21. Given that NRPE1-associated transposons were enriched for gene-proximal transposons, we investigated the relative age of NRPE1-targeted transposons. For this analysis, we used the genome of a close A. thaliana relative, A. lyrata22, to distinguish between transposons conserved in the two genomes (“ancient”, Supplementary Table 2) versus those found only in A. thaliana (“unique”) that are therefore relatively young21. We found that NRPE1-associated transposons were enriched for unique transposons (Fig. 6a) and that NRPE1-associated promoters similarly enriched for unique transposons (Fig. 6b). Moreover, when comparing unique versus ancient transposons irrespective of overlap with called NRPE1 peaks, we found that unique transposons showed a significant enrichment for NRPE1-binding (Fig. 6c, P<2.2e-16, Mann-Whitney Test). We also noted that, while unique transposons were generally more lowly expressed than ancient transposons (Supplementary Fig. 6), mutations in NRPE1 resulted in greater gains of expression for unique transposons relative to ancient transposons (Fig. 6d). While these results indicate that young transposons are a preferred target for NRPE1, it is also possible that this could also be an indirect effect of young transposons being gene-proximal as previously reported21. To control for this, we compared gene-proximal ancient transposons with gene-proximal unique transposons and found that even among the gene-proximal subset, unique transposons were enriched for NRPE1 targets as compared to ancient transposons (P<2.2e-16 Fisher’s Exact Test, Fig. 6e). These results suggests that transposon age may be a determinant of Pol V targeting, and that RdDM could be an epigenetic read out of the evolutionary history of repetitive elements in the Arabidopsis genome.

Figure 6.

NRPE1 is enriched at transposons that are relatively new in the A. thaliana genome. (a) NRPE1-associated transposons are enriched for transposons unique to A. thaliana (P<2.2e-16, Fisher’s Exact Test). (b) Relative transposon abundance (transposons per promoter/total number transposons of that type) at NRPE1-associated (+) and non-NRPE1-associated (−) promoters. (c) Metaplot showing the ChIP-seq read ratios over unique and ancient transposons. (d) Log2 ratio of RNA-seq reads in nrpe1 mutants compared to WT. (e) NRPE1 is significantly enriched at “unique” transposons found at promoters as compared to either all promoter-associated transposons or “ancient” promoter-associated transposons (P<2.2e-16, Mann-Whitney Test).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have generated the first genome-wide chromatin association profile of an RdDM component. We believe that these datasets have identified bona fide Pol V sites that are biologically significant, because epigenomic profiling indicate that these are sites of NRPE1-dependent DNA methylation and small RNA accumulation, consistent with the role of Pol V in RdDM. Additionally, the loss of NRPE1 chromatin association in mutants disrupting the DDR putative chromatin-remodeling complex further confirms the identified Pol V target sites as biologically significant.

The observation that Pol V is enriched at gene promoters is intriguing. It suggests that while Pol V has evolved from the ancestral Pol II to target de novo DNA methylation, it may retain some Pol II binding preferences for gene proximal regions. Consistent with this idea, we noted that even at promoters without defined NRPE1-peaks, we observed an enrichment of NRPE1 ChIP-seq reads near the transcriptional start site (Fig. 3c,d). This suggests a broader set of promoters than those we have identified may be transient targets of Pol V with more stable association occurring only at a subset of promoters.

The key determinants for a promoter region becoming strongly associated with Pol V are unknown, but our data indicate that the presence of a transposable element, particularly a relatively young insertion, is a major driver in the stable association of Pol V to a given genomic locus. Thus, it appears that Pol V preferentially associates at regions where promoters and transposons overlap. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that younger transposons, which tend to be close to genes, are preferential targets of Pol V. Our analysis of RNA-seq datasets shows that the endogenous protein coding genes near Pol V sites are up-regulated upon loss of RdDM effectors, indicating that the active targeting of promoters and transposons by Pol V has functional implications for the transcriptome. Furthermore, the results provide an potential explanation for previous observations that genes near methylated transposons are often associated with reduced expression21,23.

Given the observed pattern of Pol V association within the genome, it appears that Pol V transiently associates with most promoters. We hypothesize that when an active transposon jumps into a promoter region of a gene, Pol V will become more stably associated with that promoter and the associated transposon, thus targeting the transposon for de novo DNA methylation and transcriptional repression, preventing further movement of the transposon and potentially mitigating effects of the insertion on nearby genes. In this model, Pol V and RdDM have evolved to act in genome surveillance for newly inserted transposons, especially those near genes. The MET1 and CMT3 DNA methylation pathways would subsequently maintain epigenetic silencing of those targets. This idea is supported by the relatively greater loss of CHH methylation compared to CG and CHG DNA methylation in nrpe1 mutants (Fig 1c).

The results of Pol V ChIP-seq provide insights into the genome-wide targets of a non-canonical eukaryotic DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. In the future, it will be important to test if the targeting of this polymerase is solely dictated by the genomic elements suggested by this study, or if there are other chromatin-level or protein interaction components that direct recruitment.

ONLINE METHODS

Plant materials

NRPE1-FLAG12 transgenic plants and nrpe1-12 (SALK_033852)24, nrpd1-4 (SALK_083051)25, drd1-66 and dms3-48 mutant plants are in the A. thaliana Columbia ecotype. Mutant rdm1-1 was identified from ros1-1 background in C24 ecotype10. NRPE1-FLAG transgene was crossed into the drd1-6, dms3-4 and rdm1-1 mutant backgrounds.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and RNA analysis

Two grams of flower tissues were utilized for chromatin immunoprecipitation using a previously published protocol with minor modifications26, 27. Chromatin was sonicated in a Bioruptor (Diagenode) for 15 minutes of 30 s on and 30 s off, and the chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads (Sigma). The enriched DNA was ethanol precipitated and subjected to library generation following Illumina’s manufacturer instructions. ChIP-seq data were validated by independent ChIP experiments at randomly selected 9 regions (P1–P9) as well as one NP region, located between two adjacent binding peaks, served as a negative control. Only primers producing single amplification products were included for the validation analysis. Of these, regions P2 and P9 were selected as representative examples of typical NRPE1 occupancy in drd1, dms3 and rdm1 mutants. The data presented are relative to input (% input). Total RNA was isolated from flowers using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and used to synthesize first strand cDNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). Real-Time PCR was performed using the SYBR Green SuperMix (Bio-Rad) in MxPro3000 qPCR machine (Stratagene) following the manufacturer instruction. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 3.

ChIP-seq, BS-seq and smRNA-seq libraries constructions and sequencing

Small RNA was extracted and purified from floral tissue as described28. Libraries for ChIP-seq were generated using paired-end regents from NEB and adapters from the Illumina whereas smRNA-seq libraries were generated using the Illumina True-seq protocol. BS-seq libraries were generated as previously reported2. All libraries were sequenced using the HiSeq 2,000 platform following manufacturer instructions (Illumina) at a length of 50 bp. Read statistics are listed in Supplemental Table 4.

Data analyses

Sequenced reads were base-called using the standard Illumina pipeline. For ChIP-seq and BS-seq libraries, only full 50 nt reads were retained, whereas for smRNA-seq libraries reads had adapter sequence trimmed and were retained if they were between 15 nt and 30 nt in length. For ChIP-seq and smRNA-seq libraries, reads were mapped to the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR8 – www.arabidopsis.org) with Bowtie29 allowing up to 2 mismatches and retaining only reads mapping uniquely to the genome for further analysis. For the biological replicate of the ChIP-seq experiment and the ChIP-seq of DDR mutants, 50 million reads were subset from the initial approximate 200 million reads for further analysis in the interest of computational time. For BS-seq libraries, reads were mapped using the BSseeker wrapper for Bowtie30. For ChIP-seq and BS-seq, identical reads were collapsed into one read, whereas for smRNA-seq identical reads were retained.

For methylation analysis, percent methylation was calculated as previously reported2, with only cytosines having at least 5X coverage in both the WT and nrpe1 libraries included in any analysis. For all libraries the list of mRNA and transposons along with genomic coordinates were obtained from TAIR (TAIR8). For all analyses, only transposons greater than 100bp in length were used.

For analysis of the previously published mRNA-seq datasets (main text reference 17) we considered TAIR8 representative gene models within a given distance of an NRPE1 site as described in the main text. To quantify expression change we only considered genes that had at least 10 reads in any of the libraries considered (Col, ago4, drm2, or nrpe1) to filter out genes not expressed in the tissue considered.

Identification of NRPE1 peaks and calling of promoter and transposon overlaps

The R package BayesPeak31, 32 was used to identify regions of NRPE1 enrichment in our NRPE1-FLAG ChIP-seq library as compared to the Col ChIP-seq control library. To filter out false positives, we also identified peaks using a sliding window approach using a 200bp window at 50bp increments and performing a Fisher Exact Test comparison between the ChIP-seq libraries. Resulting p-values were Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted to estimate FDRs. Only high scoring peaks that overlapped from the Bayesian analysis (PP>0.99999) and the Fisher test (FDR<1e-5) were retained.

For the purposes of this study, “overlap” of NRPE1 peaks with genomic regions (promoters/transposons) is called when >=1bp of a peak overlaps with a locus. Similarly, elements were considered “proximal” if within 1kb of each other, and “distal” if farther than 1 kb from each other.

Classification of “gancient” h versus “gunique” h transposons

The list of TAIR8 transposable elements (ftp://ftp.arabidopsis.org/home/tair/Genes/TAIR8_genome_release/TAIR8_Transposable_Elements.txt) were classified as either “unique” or “ancient” using the exact methodology previously described21. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome (Araly1, unmasked) was downloaded from JGI (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Araly1/Araly1.home.html), and used to generate a BLASTable database.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Thierry Lagrange at the University de Perpignan for the NRPE1-FLAG transgenic seeds and Mahnaz Akhavan for assistance with high-throughput sequencing. X.Z. is supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service grant F32GM096483-01 (X.Z.). C.J.H. is supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation fellowship. S.F. is supported by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grant GM60398. S.E.J. is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Accession Codes: Sequencing data were deposited xxx and can be downloaded at xxx.

Note: Supplemental information is available on the Nature Structural and Molecular Biology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.Z., C.J.H. and S.E.J. designed the experiments. X.Z., C.J.H., J.A.L., L.M.J., A.T. and S.F. performed the experiments. X.Z. and C.J.H. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cokus SJ, et al. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature. 2008;452:215–219. doi: 10.1038/nature06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haag JR, Pikaard CS. Multisubunit RNA polymerases IV and V: purveyors of non-coding RNA for plant gene silencing. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:483–492. doi: 10.1038/nrm3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosher RA, Schwach F, Studholme D, Baulcombe DC. PolIVb influences RNA-directed DNA methylation independently of its role in siRNA biogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3145–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709632105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wierzbicki AT, Haag JR, Pikaard CS. Noncoding transcription by RNA polymerase Pol IVb/Pol V mediates transcriptional silencing of overlapping and adjacent genes. Cell. 2008;135:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanno T, et al. Involvement of putative SNF2 chromatin remodeling protein DRD1 in RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr Biol. 2004;14:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanno T, et al. A structural-maintenance-of-chromosomes hinge domain-containing protein is required for RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nature genetics. 2008;40:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ausin I, Mockler TC, Chory J, Jacobsen SE. IDN1 and IDN2 are required for de novo DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:1325–1327. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Law JA, et al. A protein complex required for polymerase V transcripts and RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2010;20:951–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao Z, et al. An RNA polymerase II- and AGO4-associated protein acts in RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nature. 2010;465:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng B, et al. Intergenic transcription by RNA polymerase II coordinates Pol IV and Pol V in siRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Genes & development. 2009;23:2850–2860. doi: 10.1101/gad.1868009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Shami M, et al. Reiterated WG/GW motifs form functionally and evolutionarily conserved ARGONAUTE-binding platforms in RNAi-related components. Genes & development. 2007;21:2539–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.451207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowley MJ, Avrutsky MI, Sifuentes CJ, Pereira L, Wierzbicki AT. Independent chromatin binding of ARGONAUTE4 and SPT5L/KTF1 mediates transcriptional gene silencing. PLoS genetics. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L, et al. An atypical RNA polymerase involved in RNA silencing shares small subunits with RNA polymerase II. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:91–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wierzbicki AT, Ream TS, Haag JR, Pikaard CS. RNA polymerase V transcription guides ARGONAUTE4 to chromatin. Nature genetics. 2009;41:630–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TF, et al. RNA polymerase V-dependent small RNAs in Arabidopsis originate from small, intergenic loci including most SINE repeats. Epigenetics: official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2012;7 doi: 10.4161/epi.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ausin I, et al. An IDN2-containing complex involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:8374–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206638109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Bernatavichute YV, Cokus S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. Genome-wide analysis of mono-, di- and trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome biology. 2009;10:R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slotkin R, Nuthikattu S, Jiang N. In: Plant Genome Diversity. Wendel JF, editor. Vol. 1. Springer-Verlag; Wien: 2012. pp. 35–55. Ch. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lisch D. Epigenetic regulation of transposable elements in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:43–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollister JD, Gaut BS. Epigenetic silencing of transposable elements: a tradeoff between reduced transposition and deleterious effects on neighboring gene expression. Genome research. 2009;19:1419–1428. doi: 10.1101/gr.091678.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu TT, et al. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nature genetics. 2011;43:476–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollister JD, et al. Transposable elements and small RNAs contribute to gene expression divergence between Arabidopsis thaliana and Arabidopsis lyrata. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2322–2327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018222108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pontier D, et al. Reinforcement of silencing at transposons and highly repeated sequences requires the concerted action of two distinct RNA polymerases IV in Arabidopsis. Genes & development. 2005;19:2030–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.348405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herr AJ, Jensen MB, Dalmay T, Baulcombe DC. RNA polymerase IV directs silencing of endogenous DNA. Science. 2005;308:118–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1106910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson L, Cao X, Jacobsen S. Interplay between two epigenetic marks. DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 methylation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1360–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00976-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stroud H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of histone H3.1 and H3.3 variants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:5370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203145109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu C, Meyers BC, Green PJ. Construction of small RNA cDNA libraries for deep sequencing. Methods. 2007;43:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen PY, Cokus SJ, Pellegrini M. BS Seeker: precise mapping for bisulfite sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spyrou C, Stark R, Lynch AG, Tavare S. BayesPeak: Bayesian analysis of ChIP-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cairns J, et al. BayesPeak--an R package for analysing ChIP-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:713–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.