Abstract

T2 decay during long echo trains of MR imaging pulse sequences is known to cause a blurring effect, due to the peak broadening of the Point Spread Function (PSF). In contrast, the simultaneous amplitude-loss effect, led by the peak reduction of the PSF, has gained much less attention. In this report, we analyzed the PSFs of both the truncation and T2 decay for Cartesian (linear profile ordering and low-high ordering) and spiral trajectories respectively. Then, we derived simple formulas to characterize both the blurring and amplitude-loss effects, which are functions of the ratios of the echo train duration (Tk) over T2 (Tk/T2). Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) per unit time was thus analyzed considering both the amplitude-loss effect induced by the T2 decay and the SNR gain from the long acquisition duration based on MR sampling theory. Optimum Tk/T2 ratios to achieve maximum SNR per unit time were 1.2 for the Cartesian trajectory and 0.8 for the spiral trajectory.

Keywords: Point Spread Function, T2 decay, Cartesian, Spiral, k-space trajectory, SNR per unit time

INTRODUCTION

In MRI, to exhibit proton density- or transverse relaxation time (T2)- weighted image contrast, it requires a long repetition time (TR) relative to longitudinal relaxation time (T1). When 2D high-resolution or 3D acquisitions are desired, a large k-space matrix needs to be covered efficiently. Fast imaging with different k-space trajectories include echo-planar imaging (EPI) (1) and spiral imaging (2). To mitigate effects of magnetic field inhomogeneity, fast spin-echo (FSE) (3) and gradient- and spin-echo (GRASE) sequences (4) were proposed by inserting refocusing pulses between every k-line or every few k-lines, respectively. Attempts to lengthen the acquisition window with very long echo train duration (Tk) during each TR are often made (5, 6), by assuming that this will increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) per unit time.

The effects of T2 decay during a long echo train with different k-space trajectories can be characterized using point spread functions (PSF). T2 decay has been known to cause blurring (peak broadening of PSF) mostly along the slowest encoding direction, which is the phase encoding direction in EPI and FSE (7–9), along the radial direction in spiral trajectory (10), or along the azimuthal direction in radial trajectory (11). Another undesired effect of this T2 decay during acquisition, overlooked by many, is amplitude loss of the signal (peak reduction of PSF), which offsets the SNR gain from an extended acquisition window (proportional to ). Rahmer et al. (11) analyzed the PSFs of T2 decay on radial imaging for ultrashort T2 species, and explicitly considered this amplitude-loss effect. The derivation of the formulas presented in that paper was not reported. Also only simulated results about the amplitude-loss effect were presented.

Cartesian k-space trajectory is most straightforward in MRI and is used in both 2D and 3D FSE or GRASE acquisitions. 2D spiral and 3D stack-of-spiral (2D spiral with a third slice direction) trajectories are also choices for some applications. The purpose of this work is to derive the PSF of T2 decay for pulse sequences where long Tk is often employed. For Cartesian and spiral trajectories, respectively, both blurring and amplitude-loss effects are characterized with simple analytical formulas that are related only to the ratio of Tk/T2. SNR per unit time is computed by multiplying both the amplitude-loss effect from T2 decay and the SNR gain from the long echo train duration. In this way, the optimum acquisition strategy, which results in both minimum blurring and maximum SNR efficiency, can be achieved.

GENERAL FRAMEWORK

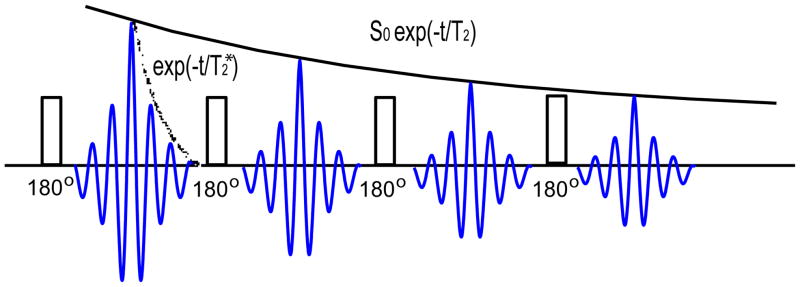

Any imaging sequence is subject to many factors associated with PSFs, including sampling, truncation, off-resonance, T2′, and T2 decay. For conventional gradient echo and spin echo sequences (single k-line per TR), a detailed analysis was provided in Haacke et al.’s book ((12), Chapter 13), and elsewhere. For FSE or GRASE sequences with long echo trains (multiple k-lines per TR), echo spacing (interval between 180° refocusing pulses) is always kept short to reduce field inhomogeneity effects. For this work, the focus is to analyze PSFs of T2 decay of refocused echoes with varying length of Tk. So that echo spacing is assumed to be constant, with Tk the only varible left to be considered. In the following analysis, T2* decay, although an additional PSF factor for the full characterization of the signal relaxation behavior, is ignored and only a spatially invariant T2 term is taken into account to investigate the effect of changing Tk.

When there is no relaxation decay during the echo train, the signal acquired with the frequency and phase encoding gradients is given by:

| (1) |

The true spatial distribution M(x, y) is a Fourier transform (FT) pair with the acquired signal S(kx(t), ky(t)):

| (2) |

The FT between the k-space and the image space is generally regarded as a linear and shift-invariant imaging system. An additional filtering function in k-space described as the Modulation Transfer Function (MTF, S(kx, ky)×MTF), has an FT pair in the spatial domain, better known as the Point Spread Function (PSF) (13).

| (3) |

where the FT of the product of the original signal function with the MTF is equal to the convolution (⊗) of their individual FTs (13).

| (4) |

If there is no additional modulation function, as for an ideal situation, MTF(kx, ky) = 1 everywhere in k-space, the corresponding PSF is a delta function, PSF(x, y) = δ(x, y). Convolution of an image with a delta function is still the original image itself.

In practice, k-space data is always acquired with a maximum spatial frequency to render a nominal resolution (Δx, Δy) (12) (as will be shown, the nominal resolution is not the same as the the full width at half maximum (FWHM)):

| (5) |

The MTF of this truncation effect is a square function (−1/2 ≤ m ≤ 1/2, Π(m) = 1; else, Π(m) = 0 ) in k-space:

| (6) |

The corresponding PSF in the spatial domain is a sinc function:

| (7) |

When there is T2 decay during the echo train, obtained signal is modulated to be:

| (8) |

Once a direct relation between t and (kx(t), ky(t)) is derived as t(kx, ky), then the filtering function in k-space can be described as:

| (9) |

The PSF, as the inverse FT of MTF, can thus be calculated. We then characterized the blurring effect using the FWHM of the PSF and the amplitude-loss effect using the peak amplitude of the PSF.

CARTESIAN TRAJECTORY

Since T2 decay effects occur mainly along the direction associated with the slowest phase encoding (7), we limited our derivation in 1D, here arbitrarily choosing the y direction for the Cartesian trajectory. The MTF of the combined truncation and T2 decay effects is:

| (10) |

For the simplicity of the derivation, the spatial frequency variable ky(t) along the phase encoding direction can be hypothetically encoded with an effective constant gradient , similar to kx(t), encoded with a readout gradient in the frequency encoding. This concept of is only introduced here to connect variables t and ky(t) during formula derivation.

This link between t and ky(t) is different for different k-space profile orderings (sometimes called view ordering). We are going to examine two popular choices: linear (or sequential); and low-high (or centric).

Linear Profile Ordering

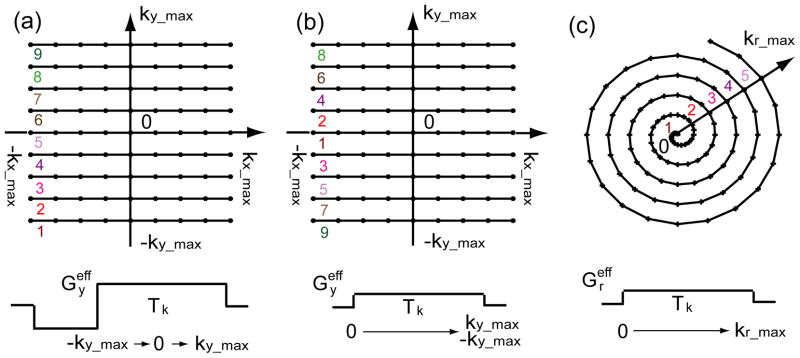

For linear profile ordering (Fig. 2(a)), with t from 0 to Tk, the effective gradient scanned k-space along the y direction starting from −ky_max first, through the center of the k-space in the middle of the echo train, and then finally to ky_max:

| (11) |

Figure 2.

Diagrams of Cartesian (a) linear profile ordering, (b) low-high profile ordering, and (c) Spiral k-space trajectories are shown. The colored numbers indicate the increasing profile orders along the slowest phase encoding direction for each trajectory. At the bottom of each diagram, an effective gradient Geff during the echo train duration Tk is plotted for each k-space trajectory, which corresponds to Eq. (11), (18), and (30) respectively.

An inverse relation would be:

| (12) |

The reciprocal formula between k-space and spatial domain (Eq. (5)), Eq. (11) leads to:

| (13) |

and Eq. (12) can be rewritten as:

| (14) |

Now with an explicit formula between t and ky(t) for linear ordering, Eq. (10) is modified as:

| (15) |

where

| (16) |

Thus, the PSF, considering both the truncation and T2 decay effect, is derived to be:

| (17) |

Note that Eq. (15) and Eq. (17), although derived based on a T2 decay modulation on a linear profile ordering of a long echo train, is actually similar to Eq. (13.53) and Eq. (13.54) in Haacke et al.’s book (12), which is based on the T2* modulation on a single k-line gradient-echo sequence.

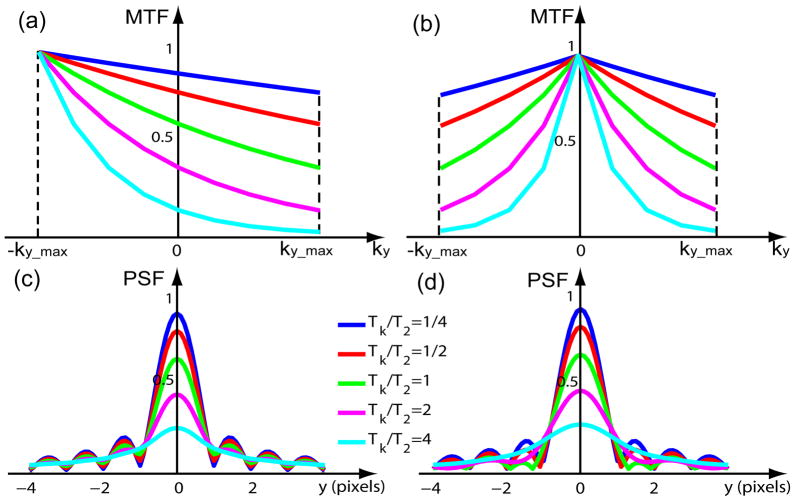

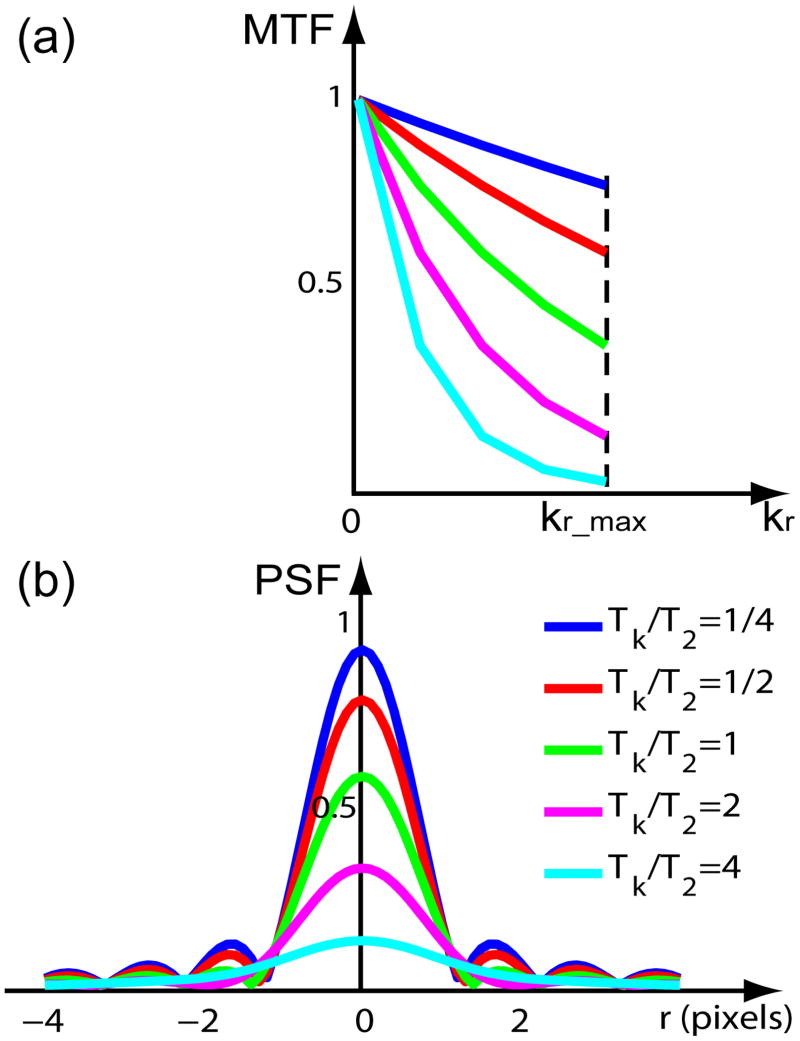

With varying Tk/T2 ratios, the MTFtrunc+decays are plotted in Fig. 3(a). The absolute magnitude of the PSFtrunc+decays, when normalized to the case of no relaxation (a = 0), are plotted in Fig. 3(c), with respect to the number of pixels away from the center (y/Δy) (11).

Figure 3.

MTFs and PSFs of both truncation and T2 decay effects for linear profile ordering and low-high profile ordering in a Cartesian trajectory, with Tk/T2 ratios = [1/4, 1/2, 1, 2, 4]. Linear ordering: (a) MTF (Eq. (15)) (c) absolute PSF (Eq. (17)); low-high ordering: (b) MTF (Eq. (21)) (d) absolute PSF (Eq. (22)).

Low-High Profile Ordering

For low-high profile ordering (Fig. 2(b)), the effective gradient fills the center of k-space (ky = 0) first and then transverses outward to the top (ky_max) and bottom (−ky_max) of the k-space together:

| (18) |

Note that Eq. (18) is an approximation by ignoring the small acquisition time difference at the k-space positions with the same distance to the center of k-space but different signs. In this case,

| (19) |

This leads to a different relation between t and ky(t):

| (20) |

Eq. (10) for low-high profile ordering is then rewritten as:

| (21) |

The corresponding PSF is:

| (22) |

For comparison with the MTFtrunc+decays and PSFtrunc+decays of linear ordering, the MTFtrunc+decays and the normalized absolute magnitude of the PSFtrunc+decays of low-high ordering are plotted in Fig. 3(b) and (d), respectively.

Blurring Effect

The blurring effects of these PSFs are typically characterized by the parameter FWHM, which describes the broadness of the peak at half the maximum magnitude. Due to the complex formula of PSFs for linear and low-high profile orders (Eqs. (17), (22)), the analytical derivation of FWHM is difficult to realize. Instead, the FWHM was measured from the plot (measuring distance between the two symmetric points on each PSF curve with half of the peak amplitude) of each PSF with varying Tk/T2 ratios (Fig. 3(c–d)). Then, the numbers were found to be best fitted as a second-order polynomial using a linear-least-square algorithm. The results are shown in Fig. 4(a). For linear k-space ordering:

| (23) |

and low-high k-space ordering:

| (24) |

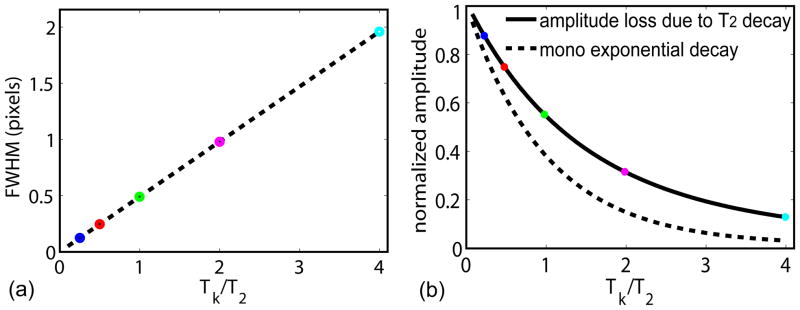

Figure 4.

For a Cartesian trajectory: (a) FWHM (normalized to nominal resolution, unit in pixels) of the blurring effect of linear profile ordering (Eq. (23)) and low-high profile ordering (Eq. (24)), respectively. The two curves converge around 1.21 pixels, which is the FWHM with only the truncation effect (Tk≪T2) (Eq. (25)). (b) Amplitude-loss effect of both k-space orderings are the same (Eq. (28)), and referenced with a mono-exponential decay function, exp(−Tk/T2). (c) Normalized SNR per unit time, calculated as the product of Eq. (28) and , as a function of Tk/T2. The circles with five different colors are from the respective Tk/T2 ratios shown in Fig. 3.

If T2 decay is ignored during the k-space trajectory (Tk ≪ T2), the MTF and PSF are governed only by the truncation effect, as expressed in Eq. (6) and Eq. (7), respectively. The FWHM due to the truncation effect is determined as

| (25) |

which is identical to the result shown in Rahmer et al.’s Table 1 (11).

It is not surprising to find that the constant terms in the fitted results of Eq. (23) and (24) are both close to the theoretical value in Eq. (25), reflecting the truncation effect as the limit of a PSF with very short Tk/T2 ratios. The additional terms with first and second order polynomials indicate the effect of T2 decay, which shows that the linear ordering has a slightly less blurring effect compared to the low-high ordering. This is probably due to the fact that the low-high ordering clearly looks like a low-pass filter (Fig. 3(a) compared with (b)), whereas the linear ordering is not so obvious with a more or less constant transfer when positive and negative spatial frequencies are averaged. Effects of T2-dependent blurring with different profile ordering in FSE sequences have been studied by Mulkern et al. decades ago (14). Although those authors compared more types of the profile ordering (their Fig. 1(A) and 1(C) correspond to our linear and low-high orderings respectively), we have provided direct analytical results of PSFs (Eqs. (17) (22)) and associated FWHM (Eqs. (23) (24)), which are simple to interpret with only variables of Tk/T2 ratios.

Figure 1.

A diagram of multiple echos along the phase encoding direction is shown. Both T2* decay of signals before being refocused by 180 pulses and T2 decay of refocused echoes are illustrated.

Amplitude-Loss Effect

The amplitude-loss effect can be described by the peak magnitude of each PSF (y=0) in the spatial domain, which is equal to the area of the MTF in k-space, as derived from Eq. (3). Calculation in either domain for both k-space orderings all lead to:

| (26) |

When normalized to the case of only the truncation effect (Eq. (7)), with no relaxation decay (Tk ≪ T2), which corresponds to a = 0:

| (27) |

Thus the amplitude-loss effect for a Cartesian trajectory is characterized by a function:

| (28) |

Eq. (28) applies to both linear and low-high profile orderings. The MTFtrunc+decay have the same weighting functions except with different orderings, which lead to identical areas of MTFs in k-space, or the same peak magnitudes of PSFs in image space. This function is plotted in Fig. 4(b), and also compared with a more familiar function exp(−Tk/T2). The center of PSF decays more slowly than the mono-exponential function does, which reflects the difference between the area of MTFtrunc+decay and its boundary value at ky_max, which decays at a mono-exponential rate T2.

Amplitude-loss effects, due to T2 decay for 1D, 2D, and 3D radial k-space trajectories, were demonstrated by Rahmer et al. in their Fig. 3 (11). We have derived a simple analytical formula (Eq. (28)) with respect to Tk/T2 ratios. As shown in Fig. 4(b) (circles with varying colors), for Tk/T2 = [1/4, 1/2, 1, 2, 4], the amplitude losses are [0.88, 0.79, 0.63, 0.43, 0.25], respectively.

Effect on SNR Per Unit Time

The amplitude-loss effect reduces available SNR for imaging monotonically with longer Tk. However, based on MR sampling theory (12, Chapter 15), the SNR per unit time is a time-normalized SNR on a per square root of time basis, which is proportional to for a given readout time during each echo spacing. When multiplying these two effects with opposite trends between SNR and Tk together, Fig. 4(c) shows that the optimum SNR per unit time is obtained when Tk/T2 is about 1.2. When the T2-decay induced amplitude-loss is not neglected, the SNR per unit time at Tk/T2 =4 is only 77% of the maximum at Tk/T2 =1.2, rather than a factor of sqrt(4/1.2)=1.8 times higher if only the gain from a longer sampling time were considered. This result is similar to the conclusion from another work (11).

SPIRAL TRAJECTORY

Rather than a Cartesian coordinate using x and y, a polar coordinate using r and Θ better describes the spiral trajectory. The spiral k-space data is also acquired with a maximum spatial frequency to render a nominal resolution (Δr) in the radial direction:

| (29) |

Typically, the spiral trajectory (Fig. 2(b)) begins at the center of k-space (kr = 0) and then spirals outward to the maximum of k-space, kr_max. The slowest phase encoding is along the radial direction with an effective gradient :

| (30) |

Then

| (31) |

The MTF of the combined truncation and T2 decay effects for the spiral trajectory is thus:

| (32) |

where

| (33) |

Given the circularly symmetric property of the radial function, a 2D FT can be reduced to a 1D zero-order Hankel transform (13). Thus, the corresponding PSF with both truncation and T2 decay effects for a spiral trajectory is:

| (34) |

where J0(rkr) is a Bessel function of order zero. Eq. (34) is difficult to derive a closed formula analytically. An alternative way is to derive separate PSFs for the truncation effect (PSFtrunc) and T2 decay effect (PSFdecay) since these effects are easier to analyze individually (11).

The Hankel transform of the truncation effect, which is a disk function in k-space, is a Jinc function in the spatial domain (15):

| (35) |

And the Hankel transform of the T2 decay effect is formulated as:

| (36) |

From Lipschitz’s integral ((15), p58):

| (37) |

Therefore, Eq. (36) is derived as:

| (38) |

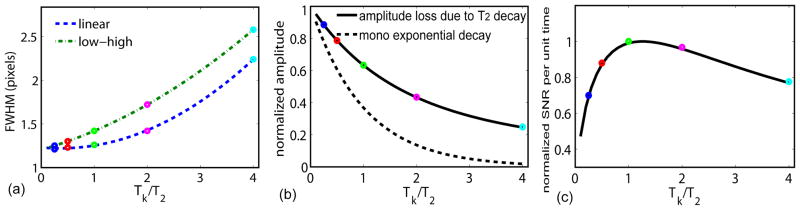

The MTFtrunc+decays of varying Tk/T2 ratios are illustrated in Fig. 5(a). The PSFtrunc+decay for the spiral trajectory is then calculated through the convolution of PSFtrunc (Eq. (35)) and PSFdecay (Eq. (38)) of the corresponding Tk/T2 ratios, and the final results are plotted in Fig. 5(b), with respect to the number of pixels away from the center (r/Δr).

Figure 5.

MTF (a) and PSF (b) for a spiral trajectory with both truncation and T2 decay effects, with Tk/T2 ratios = [1/4, 1/2, 1, 2, 4].

Blurring Effect

The FWHM due to the truncation effect is determined by the Jinc function J1(rkr_max)/(rkr_max):

| (39) |

From Eq. (38), the FWHM due to the T2 decay effect can be readily calculated as:

| (40) |

Eq. (39) and Eq. (40) are identical to the results shown in Rahmer et al.’s Table 1 ((11), 2D radial).

For the combined effects of truncation and T2 decay, direct measuring of FWHM from the plot of each PSFtrunc+decay with varying Tk/T2 ratios (Fig. 5(b)) were performed. The numbers were fitted (linear-least-square) again as a second-order polynomial.

| (41) |

This FWHM relation with the Tk/T2 ratio is plotted in Fig. 6(a). Similar to the Cartesian case (Eqs. (23) and (24)), the constant term in Eq. (41) is also close to Eq. (39), reflecting the limiting case of a PSF with a very small Tk/T2 ratio, which is only due to the truncation effect of the PSF.

Figure 6.

For a spiral trajectory: (a) FWHM of the blurring effect (Eq. (41)). (b) Amplitude-loss effect (Eq. (44)), also referenced with a mono-exponential decay function, exp(−Tk/T2). (c) Normalized SNR per unit time, calculated as the product of Eq. (44) and , as a function of Tk/T2.

Amplitude-Loss Effect

Similarly, the peak center of the PSF in spatial space is calculated to estimate the amplitude loss from the T2 decay effect. Since J0(0) = 1, we have:

| (42) |

When normalized to the case of only the truncation effect (Eq. (35)), ignoring the relaxation effect (Tk ≪ T2, corresponding to b = 0),

| (43) |

Thus, the amplitude-loss effect for a spiral trajectory is:

| (44) |

This function is plotted in Fig. 6(b), again referenced with the function exp(−Tk/T2). As shown in Fig. 6(b) (circles with varying colors), for Tk/T2 = [1/4, 1/2, 1, 2, 4], the amplitude-losses are [0.85, 0.72, 0.53, 0.30, 0.11], respectively. Compared with Fig. 4(b), the amplitude-loss effect of the spiral trajectory decays faster than that of the Cartesian trajectory does. This demonstrates the influence of the choice of the k-space trajectory on the T2-induced amplitude loss.

Effect on SNR per Unit Time

Fig. 6(c) shows that the optimum SNR per unit time for the 2D spiral trajectory is obtained when Tk/T2 is about 0.8. When the T2-decay induced amplitude loss is not neglected, the SNR per unit time at Tk/T2 =4 is only 43% of the maximum at Tk/T2 =0.8, rather than a factor of sqrt(4/0.8)=2.2 times higher if only the gain from a longer sampling time were considered. These findings are similar to the results in another work ((11), Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Different k-space trajectories suit for different MRI applications. Cartesian linear profile ordering is mostly used in T2-weighted imaging with the effective echo time (echo at the center of k-space) in the middle of the echo train; Cartesian low-high profile ordering, instead, is often chosen for applications preferring the echo time in the beginning of the echo train, such as proton density-weighted imaging, and quantitative mapping of tissue magnetic properties (T1, T2) or physiology values (diffusion, perfusion, etc.); Spiral trajectory is the alternative to Cartesian low-high profile ordering with the advantage of less sensitivity to motion (8).

For Cartesian and spiral trajectories, respectively, the influences of the truncation and T2 decay during the long echo train with duration Tk were analyzed using Point Spread Functions. Necessary approximations were made to derive mathematical models that are analytically solvable. Both blurring effects (peak broadening) and amplitude loss effects (peak reduction) are accounted for using the simple formulas derived here. From the perspective of SNR per unit time for imaging, the optimum Tk/T2 ratios are 1.2 for a Cartesian trajectory (Fig. 4(c)) and 0.8 for a spiral trajectory (Fig. 6(c)), respectively. When Tk/T2 is around 1, the corresponding FWHMs of all the trajectories discussed here are only less than or equal to 1.5 pixels (Fig. 4(a) and Fig. 6(a)). At the optimum Tk/T2 for SNR per unit time, the FWHMs do not increase much, compared to the case when Tk/T2 is 0 (truncation effect only), which results in 1.2 pixels for a Cartesian trajectories (Eq. (25)) and 1.4 pixels for a Spiral trajectory (Eq. (39)). Choices of much smaller Tk/T2 ratios would not reduce much of the blurring effect because the truncation effect dominates in this limit, but would cause a loss of SNR per unit time; choices of much larger Tk/T2 ratios would have obvious disadvantages on both blurring and SNR per unit time.

From the demonstration above, it is obvious that these two adverse effects make the choice of Tk/T2 an important parameter to consider in MRI pulse sequence design. When the tissue of interest with a short T2 is imaged, a short Tk is desirable to avoid severe T2 decay during the long echo train. For some other tissues with very long T2, such as the CSF, a much longer Tk can be utilized to improve acquisition efficiency (16). For applications that the SNR is rich for taking, then it might be a trade-off between some blurring effect and a savings in time. But for applications where SNR is low and large number of averages is needed, such as some quantitative measurements, then SNR per unit time is a primary concern for the pulse sequence. In the latter case, within a given total measurement time, it would be better to acquire images with interleaved k-space trajectories with optimal Tk per interleave as suggested above, and less number of averages instead. This will help achieve both minimum blurring and maximum SNR of the images.

It is worth noting that, while it is important to understand how the choice of parameters affects SNR of a point object as demonstrated in this paper, contrast between two non-point objects are of more clinical importance for diagnostic purposes. The choice of Tk may be based on the difference in T2 values between a structure of interest and the background, and the desired resolution we need to visualize. So, in these circumstances, pulse sequence design should not necessarily aim to only optimize for SNR of a point object. However, better understanding of SNR of different tissue with different T2 values will help optimize the contrast to noise ratio.

Acknowledgments

Grant support from: NIH P41 EB015909

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. James Pekar and Peter van Zijl are thanked for helpful discussions. Mary McAllister is acknowledged for her editorial assistance. The constructive critics and helpful suggestions from reviewers are deeply appreciated.

Footnotes

Prepared for submission as a research paper in Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mansfield P. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J PhysC: Solid State Phys. 1977;10:L55–L58. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn CB, Kim JH, Cho ZH. High-speed spiral echo-planar NMR imaging - 1. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1986;MI-5:2–7. doi: 10.1109/TMI.1986.4307732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hennig J, Nauerth A, Friedburg H. RARE imaging: a fast imaging method for clinical MR. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3:823–833. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshio K, Feinberg DA. GRASE (Gradient- and spin-echo) imaging: a novel fast MRI technique. Magn Reson Med. 1991;20:344–349. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910200219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunther M, Oshio K, Feinberg DA. Single-shot 3D imaging techniques improve arterial spin labeling perfusion measurements. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:491–498. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Seara MA, Edlow BL, Hoang A, Wang J, Feinberg DA, Detre JA. Minimizing acquisition time of arterial spin labeling at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1467–1471. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oshio K, Singh M. A computer simulation of T2 decay effects in echo planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1989;11:389–397. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farzaneh F, Riederer SJ, Pelc NJ. Analysis of T2 limitations and off-resonance effects on spatial-resolution and artifacts in echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:123–139. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constable RT, Gore JC. The loss of small objects in variable TE imaging: implications for FSE, RARE, and EPI. Magn Reson Med. 1992;28:9–24. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noll DC, Cohen JD, Meyer CH, Schneider W. Spiral K-space MR imaging of cortical activation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5:49–56. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmer J, Bornert P, Groen J, Bos C. Three-dimensional radial ultrashort echo-time imaging with T2 adapted sampling. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1075–1082. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles And Sequence Design. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bracewell RN. The Fourier transform and its applications. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulkern RV, Wong ST, Winalski C, Jolesz FA. Contrast manipulation and artifact assessment of 2D and 3D RARE sequences. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:557–566. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90132-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman F. Introduction to Bessel Functions. New York: Dover; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin Q. A simple approach for three-dimensional mapping of baseline cerebrospinal fluid volume fraction. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:385–391. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]