Abstract

Several criteria have been proposed for defining cyberbullying to young people, but no studies have proved their relevance. There are also variations across different countries in the meaning and the definition of this behavior. We systematically investigated the role of five definitional criteria for cyberbullying, in six European countries. These criteria (intentionality, imbalance of power, repetition, anonymity, and public vs. private) were combined through a set of 32 scenarios, covering a range of four types of behaviors (written-verbal, visual, exclusion, and impersonation). For each scenario, participants were asked whether it was cyberbullying or not. A randomized version of the questionnaire was shown to 295 Italian, 610 Spanish, 365 German, 320 Sweden, 336 Estonian, and 331 French adolescents aged 11–17 years. Results from multidimensional scaling across country and type of behavior suggested a clear first dimension characterized by imbalance of power and a clear second dimension characterized by intentionality and, at a lower level, by anonymity. In terms of differences across types of behaviors, descriptive frequencies showed a more ambiguous role for exclusion as a form of cyberbullying, but general support was given to the relevance of the two dimensions across all the types of behavior. In terms of country differences, French participants more often perceived the scenarios as cyberbullying as compared with those in other countries, but general support was found for the relevance of the two dimensions across countries.

Introduction

Several cyberbullying definitions have been proposed in the literature, and there is still a debate within the scientific community about a common conceptualization of the phenomenon.1–4 Cultural aspects can play a role in the definition of cyberbullying since countries might use different words to describe aggressive acts such as bullying.2,5,6 In addition there is a lack of cross-national comparison data in the field of cyberbullying research. Researchers have pointed toward the importance to reach consensus about the definition to use because different operationalization and conceptualization can affect the estimates of involvement in the phenomenon and consequently can affect also the rationale for intervention.1,7 Starting from these considerations, the present study addresses the issue of cyberbullying definition across six European countries, using data from a cross-national study.

Definition of cyberbullying

During recent years researchers have debated whether the three criteria proposed by Olweus8 for defining conventional bullying, namely, intentionality, repetition, and imbalance of power, also apply to cyberbullying.1,9–13

Intentionality

Qualitative research has found that young people consider that the perpetrator must have the intent to harm another person in order to define this behavior as cyberbullying.2,11,12,14

Repetition

In the virtual context a single aggressive act can lead to an immense number of repetitions of the victimization, without the contribution of the perpetrator.1,2,12,15,16 This leads to the question whether the use of repetition may be less reliable as a criterion for cyberbullying.4

Imbalance of power

This criterion describes that someone who is more powerful in some way targets a person with less power.17 The imbalance of power causes a feeling of powerlessness for the victim and also makes it difficult to defend oneself.8,18 Some researchers19 have proposed that the criterion of imbalance of power differs in cyberbullying, since the victims can choose between more coping strategies than in conventional bullying.

Two additional criteria have been proposed that might be specific to cyberbullying: anonymity, and public versus private.2,8,16,20

Anonymity

The possible anonymity of the perpetrator is a unique feature of cyberbullying,14,15,21–23 and it may intensify negative feelings in the victim, such as powerlessness.2,12,15,16,24

Public versus private

Young people consider the attack as more serious when an embarrassing picture is uploaded to a webpage that makes it public, than when something nasty is written privately, because of the potentially large audience.2,16

Cross-cultural comparison of terms and definition for cyberbullying

The literature on cyberbullying illustrates that there are a variety of terms for the phenomenon depending on which acts are considered in the definition, such as Internet harassment, online harassment, and online bullying,2,3,25 or on cultural aspects, such as cybermobbing in Germany, virtual- or cyberbullying in Italy, harassment or harassment via Internet or mobile phone in Spain.2 Although cultural specificities exist in relation to the term used to label cyberbullying behaviors, a qualitative study showed that the definition of the phenomenon through the five criteria seems to be generally the same across countries.2

Types of cyberbullying

Studies have shown that different types of cyberbullying can be differentiated with regard to aspects, such as the covert or overt nature of the acts, the electronic devices/media used to bully others, or specific behaviors.9,14,16,21,26,27 Starting from Willard's listing of cyberbullying behaviors, Nocentini et al.2 used a classification based on the nature of the attack.28 Written-verbal includes acts using the written or the verbal form of bullying (i.e., phone calls, text messages, and e-mails). Visual involves attacks perpetrated by the use of visual forms of bullying (i.e., posting compromising images). Impersonation refers to more sophisticated attacks making use of identity theft (i.e., revealing personal information using another person's account). Exclusion is related to the designation of who is a member of the in-group and who is an outcast (i.e., purposefully excluding someone from an online group).

Aims

We aimed to evaluate the definition of cyberbullying among adolescents, in relation to five criteria: intentionality, repetition, imbalance of power, anonymity, and public versus private. In line with previous research on bullying definition,5 this was operationalized in terms of applicability of the label to a selection of 32 scenarios displaying situations that might or might not be cyberbullying, on the basis of the five criteria. Analyses take into account two criterion variables: (1) country and (2) type of behaviors.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study was part of a cross-national study developed within the European project COST Action IS0801 “Cyberbullying: Coping with negative and enhancing positive uses of new technologies, in relationships in educational settings.” Participants were 2,257 adolescents from middle to high schools across six European countries: Italy, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Estonia, and France (see Table 1 for descriptive data).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| N | Gender | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 295 (13%) | M=121; F=174 | 7 (n=85); 8 (n=85); | 13.50 (DS=1.30) |

| 9 (n=88); 10 (n=37) | ||||

| Spain | 610 (27%) | M=295; F=315 | 7 (n=319); 10 (n=291) | 13.71 (DS=1.74) |

| Germany | 365 (16%) | M=179; F=186 | 6 (n=194); 9 (n=171) | 12.89 (DS=1.61) |

| Sweden | 320 (14%) | M=160; F=160 | 6 (n=160); 9 (n=160) | 13.51 (DS=1.51) |

| Estonia | 336 (15%) | M=173; F=163 | 5 (n=95); 6 (n=68); | 14.04 (DS=1.46) |

| 7 (n=10); 8 (n=121); 9 (n=42) | ||||

| France | 331 (15%) | M=164; F=163 | 7 (n=143); 9 (n=188) | 14.24 (DS=1.07) |

| Total | 2257 | M=1092; F=1161 | 5 (n=95); 6 (n=422); | 13.64 (DS=1.56) |

| 7 (n=557); 8 (n=206); 9 (n=649); 10 (n=328) |

Assessment in each country took place in the autumn of 2010. Trained researchers administered questionnaires to students in classes during school time. In France, Germany, and Italy, consent procedure for research consisted of an approval by the school and a parental consent. In Sweden the consent procedure consisted of a school approval and parental consent for children 12 years old. In Estonia and Spain only an approval by the school was needed. All questionnaires across countries were returned anonymously.

Measure

A set of 32 scenarios was created combining the presence or absence of the criteria (see Table 2 for definitions of the five criteria, and Appendix Table A1 for the presence/absence of the criteria for all 32 scenarios). In addition, four types of behavior were covered: written-verbal (“… M. sent to C. a nasty text message …”), visual (“… M. sent to C. a compromising photo …”), exclusion (“… M. took C. off their online group …”), and impersonation (“… M. has got access to C.'s password or private information …”), giving a total number of 128 cyberbullying scenarios (CBSs).

Table 2.

Sentences Used for the Definition of the Presence/Absence of the Criteria

| Criterion | Absence of the criterion | Presence of the criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Intentionality | “as a joke” | “to hurt him/her” |

| Imbalance of power | the victim “didn't care” | the victim “was upset and didn't know how to defend himself/herself” |

| Repetition | “last month” | “every week for a month” |

| Public vs. private | sending only to the victim | sending the message “to other people to see” |

| Anonymity | “a familiar boy/girl” | “using an anonymous number” and “who didn't know him/her personally” |

Examples for impersonation type:

Scenario n. 1—no criteria: “Once M. has got access to a familiar boy/girl's—C.—password or private information as a joke. C., who noticed that, didn't care.”

Scenario n. 21—all criteria: “M. has got access to C.'s password or private information sending them out for other people to see several times during the last month to intentionally hurt C. C., who noticed that but didn't know who it was, was upset and didn't know how to defend himself/herself.”

Eight versions of questionnaire were created, each comprising 16 scenarios (8 scenarios of one type of behavior and 8 of another). The eight versions together included the complete set of the scenarios and were administrated randomly to the participants. Participants were asked of each scenario, whether it was cyberbullying or not. Preliminary focus groups, carried out before the construction of the scenarios, were conducted in each country to find the best term to label cyberbullying. All these focus groups were carried out with middle and high school adolescents and they followed the same guidelines as reported by Nocentini et al.2 In Italy adolescents preferred the term “cyberbullismo” (cyberbullying), in Germany “cyber-mobbing,” in Spain “acoso (harassment) via Internet or mobile phone”,2 in Sweden “mobbning or nätmobbning”,29 in France “cyber-violence,” and in Estonian “kiusamine” (bullying). The first version of the scenarios was devised in English by the Italian group and was then translated and back-translated by each country team in order to reach a good level of equivalence.

Data analysis

The analyses proceeded through two lines of investigation: (1) the variability across country; (2) the variability across different types of behavior. The same steps of analyses were followed for each line. First of all, descriptive percentages of “yes, it's cyberbullying” for the 32 scenarios are presented, using the χ2 test with a significance level at p-value<0.001 for differences between countries (1) and types of behavior (2). Second, to analyze the underlying structure of the relationship between scenarios, multidimensional scaling (MDS) was used. Starting from similarity or dissimilarity data on a set of objects, MDS attempts to model such data as distance between points in a geometrical space.30 Following the same method as Smith et al.,5 we calculated the percentages of participants who defined each scenario as cyberbullying for the six countries separately (1) and for the four types of behavior separately (2). We did not use data from scenario n.1 because this was the control scenario (see Appendix). Our analyses were accomplished by PROXSCAL (SPSS) using ordinal MDS. Generalized Euclidean model was used to weight the underlined dimensions by each country (1) and each type of behavior (2).30 To identify the best configuration, we compared one-, two-, three-, and four-dimension models using the normalized stress value for each solution.31

Results

Analyses by country

Descriptive data

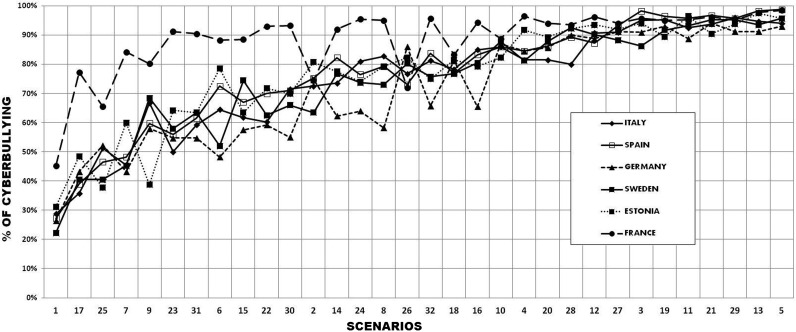

Figure 1 presents the percentages of “cyberbullying” responses, by country, for each scenario ordered by increasing average score.

FIG. 1.

Descriptive frequencies by country for each scenario.

The χ2 tests by country showed significant differences for the majority of scenarios (see Table 3): except for scenario n. 3, for all the other scenarios France reported higher percentage of cyberbullying responses as compared to the other countries.

Table 3.

Chi-square Differences Across Countries

| Scenarios | Chi-square | Significant comparisons based on standardized residuals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45.389*** | France vs. Sweden |

| 3 | 32.512*** | Sweden vs. Spain |

| 4 | 46.914*** | France vs. Italy, Spain, and Sweden |

| 6 | 135.795*** | France vs. Italy, Germany, and Sweden |

| 7 | 142.028*** | France vs. Italy, Spain, Germany, and Sweden |

| 8 | 104.292*** | France vs. Germany and Sweden |

| 9 | 132.769*** | France vs. Estonia |

| 14 | 74.901*** | France vs. Italy and Germany |

| 15 | 88.728*** | France vs. Italy, Germany, and Estonia |

| 16 | 73.607*** | France vs. Germany and Estonia |

| 17 | 141.008*** | France vs. Italy, Spain, Germany, and Sweden |

| 22 | 105.901*** | France vs. Italy, Germany, and Sweden |

| 23 | 140.530*** | France vs. Italy, Spain, Germany, and Sweden |

| 24 | 89.240*** | France vs. Germany, Sweden, and Estonia |

| 25 | 65.679*** | France vs. Sweden and Estonia |

| 30 | 107.641*** | France vs. Germany and Sweden |

| 31 | 108.420*** | France vs. Italy, Spain, and Germany |

| 32 | 83.986*** | France vs. Germany and Estonia |

All the differences are significant at level: <.001.

Multidimensional scaling

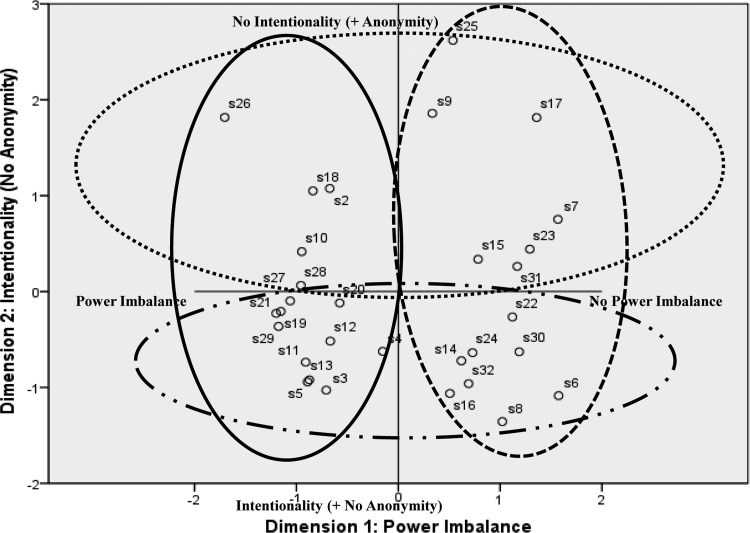

The stress values for one-, two-, three-, and four-dimensional solutions were 0.034, 0.015, 0.008, and 0.004, respectively. These values, together with the inspection of the “scree plot,” suggested that the two-dimensional solution was the best. The level of variance explained by the two-dimensional configuration is 96%. The two-dimensional MDS solution is shown in Figure 2.*

FIG. 2.

Multidimensional scaling solution of scenarios' structure for two dimensions (by country).

Notes: ________=presence of imbalance of power; -----------=absence of imbalance of power; —··—··—=presence of intentionality; ··········=absence of intentionality. s2–s32: scenarios.

The first dimension (horizontal axis) is defined by the imbalance of power criterion. Scenarios on the left-hand side are characterized by the presence of imbalance of power, and scenarios on the right-hand side are characterized by its absence. The second dimension (vertical axis) is defined by intentionality. Scenarios on the bottom-hand side are intentional, except for three (n. 4, 20, and 12), and all the scenarios on the top-hand side are nonintentional. At the same time, it should be noted that the majority of scenarios on the bottom-hand side of the figure are also characterized by the absence of anonymity (n. 8, 6, 16, 3, 5, 13, 11, 14, 4, and 12) and that the majority of scenarios on the top-hand side of the figure are also characterized by the presence of anonymity (n. 25, 26, 17, 18, 23, 31, and 28).

In Table 4 the “dimension weights” for each country are reported. The high dimension weight in the first dimension shows the strong relevance of imbalance of power in the evaluation of scenarios for all countries. The second dimension shows a much lower relevance as compared with the first dimension, for all countries: it does show slight country differences, with Estonia and France reporting the highest values and Italy and Germany the lowest.

Table 4.

Dimension Weights for Each Country on the Two Multidimensional Scaling Dimensions

| |

Dimension |

|

|---|---|---|

| Power imbalance | Intentionality (and anonymity) | |

| Italy | 0.685 | 0.073 |

| Spain | 0.682 | 0.122 |

| Germany | 0.690 | 0.060 |

| Sweden | 0.679 | 0.116 |

| Estonia | 0.647 | 0.222 |

| France | 0.662 | 0.203 |

Analyses by type of behaviors

Descriptive data

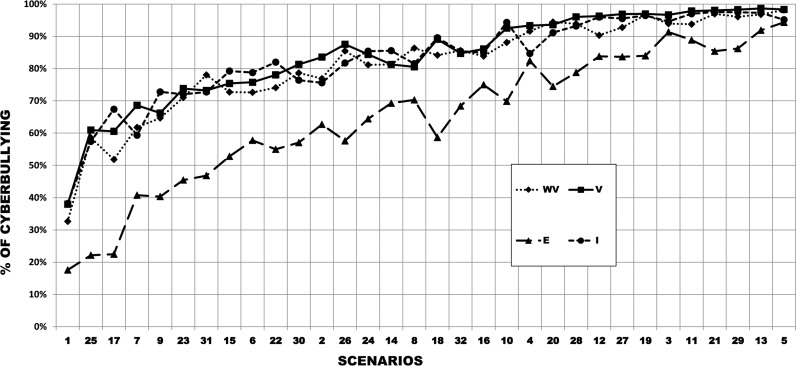

Figure 3 presents the percentages of cyberbullying responses, by type of behavior, in each scenario ordered by increasing average score. The χ2 tests by type showed significant differences in relation to 29 of the 32 scenarios (see Table 5). For all of these scenarios, exclusion showed lower percentages as compared with the other types of behavior.

FIG. 3.

Descriptive frequencies by type for each scenario.

Table 5.

Chi-square Differences Across Types of Behavior

| Scenarios | Chi-square | Significant comparisons based on standardized residuals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48.097*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 2 | 44.184*** | Exclusion vs. visual |

| 4 | 29.095*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 6 | 46.751*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 7 | 63.693*** | Exclusion vs. visual |

| 8 | 31.429*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 9 | 92.299*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 10 | 115.317*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 11 | 34.482*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 12 | 49.317*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 13 | 26.095*** | Exclusion vs. visual |

| 14 | 32.814*** | Exclusion vs. impersonation |

| 15 | 72.353*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 17 | 164.097*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 18 | 143.662*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 19 | 70.619*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 20 | 90.721*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 21 | 75.020*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 22 | 75.078*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 23 | 83.603*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 24 | 60.027*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 25 | 144.075*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual, and impersonation |

| 26 | 118.626*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual |

| 27 | 51.886*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 28 | 76.194*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual |

| 29 | 63.949*** | Exclusion vs. visual and impersonation |

| 30 | 65.481*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual |

| 31 | 95.770*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, visual |

| 32 | 48.559*** | Exclusion vs. written-verbal, impersonation |

All the differences are significant at level: <.001.

Multidimensional scaling

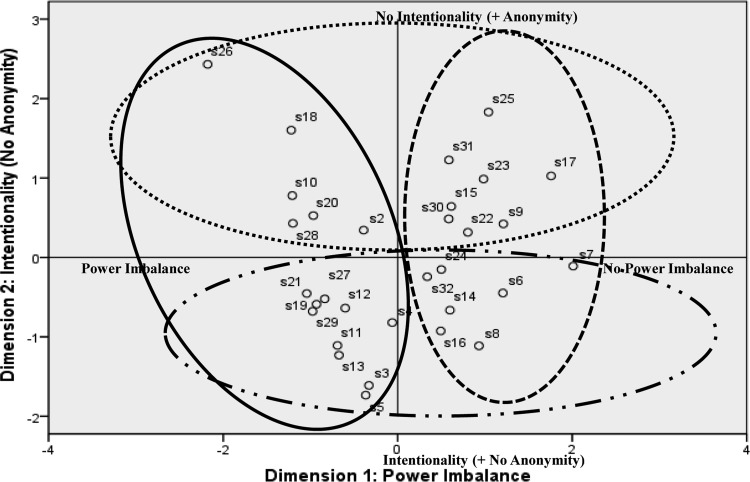

The stress values for one-, two-, three-, and four-dimensional solutions were 0.016, 0.007, 0.004, and 0.004, respectively. These values, together with the inspection of the “scree plot,” suggested that the two-dimensional solution was the best one. The level of variance explained by the two-dimensional configuration is 99%. The two-dimensional MDS solution is shown in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Multidimensional scaling solution of scenarios' structure for two dimensions (by type).

Notes: ________=presence of imbalance of power; -----------=absence of imbalance of power; —··—··—=presence of intentionality; ··········=absence of intentionality. s2–s32: scenarios.

The first dimension is again clearly defined by the imbalance of power criterion. The second dimension is defined by intentionality, but with some exceptions: n. 4, 12, and 7 on the bottom-hand side and n. 22 and 30 on the top-hand side. It should be noted that the majority of scenarios on the bottom-hand side of the figure are also characterized by the absence of anonymity (n. 8, 3, 5, 13, 11, 16, 4, 14, 12, 6, and 7) and that the majority of scenarios on the top-hand side of the figure are also characterized by the presence of anonymity (n. 25, 26, 18, 31, 17, 23, 20, 30, 28, and 22).

In Table 6 the “dimension weights” for each type are given. The high dimension weight for the first dimension shows the strong relevance of imbalance of power in the evaluation of scenarios by each type of behavior. The second dimension has a much lower relevance as compared with the first dimension for each type of behavior: it has a slight variation across type, with exclusion and impersonation having the highest values, and written-verbal and visual the lowest.

Table 6.

Dimension Weights for Each Type of Behavior on the Two Multidimensional Scaling Dimensions

| |

Dimension |

|

|---|---|---|

| Power imbalance | Intentionality | |

| Written-verbal | 0.691 | 0.049 |

| Visual | 0.692 | 0.049 |

| Exclusion | 0.683 | 0.128 |

| Impersonation | 0.684 | 0.100 |

Discussion

Overall the present study gives important insights into how adolescents define cyberbullying. This is the first study conducted in different countries, systematically manipulating the three “traditional bullying criteria” (intentionality, repetition, and imbalance of power) and the two new “specific cyberbullying criteria” (public vs. private and anonymity) in order to test their relevance for adolescent's definition, taking into account different types of cyberbullying behaviors.

Using the scenarios developed, we were able to discriminate the relevance of different criteria. The MDS analyses across country and types of behavior suggested a clear first dimension characterized by imbalance of power and a clear second dimension characterized by intentionality and, at a lower level, by anonymity. This shows that when adolescents evaluate a scenario as cyberbullying they mainly consider the presence of the traditional bullying criteria with an exception: the criterion of repetition. This is arguably not so important in the virtual context, because the nature of Information and Communication Technology can lead to an immense number of victimizations without the contribution of the perpetrator.2,4,15

The strongest criterion needed to define cyberbullying is imbalance of power, in this study defined as consequences on the victim who was upset and did not know how to defend him/herself. The relevance of this criterion is confirmed across all the countries and across all the types of behavior. It is also more relevant than intentionality, and we might ask why. Research on bullying has highlighted the dynamic between the bully's power and the weakness (social, psychological, or physical) of the victim who cannot easily defend him/herself.8 Our definition of imbalance of power focused on the consequences for the victims. In face-to-face contexts, bullies have been described as more popular, smarter, and stronger.8 But the imbalance of power is not simply based on the social status of bullies, it is also based on the microprocess of action and reaction. If the bully attacks and the victim is upset and does not know how to defend him or herself, then this creates the imbalance within the dyad and, by definition, a bullying attack. Our definition of power imbalance did not specify why the victim cannot defend him/herself or why he/she is weak as compared with the perpetrator, but it gives a clear information about the reaction of the victim and about his/her status in the relationship. This definition introduces a more interactional description of imbalance of power criterion which needs further investigation.

The second dimension that emerged from the MDS is intentionality. This is part of the definition of general aggressive behaviors.8 Almost all the definitions of bullying and cyberbullying include this attribute,15 and several studies have confirmed that the perpetrator must have the intention to harm in order for it to be defined as cyberbullying, otherwise the behavior is perceived as a joke.2, 12–14 The present findings clearly support this view.

Finally, another criterion seems to define the second dimension together with intentionality: the anonymity. When the imbalance of power is not present, we have a higher probability to perceive it as cyberbullying if the attack is intentional and nonanonymous and a lower probability if the attack is nonintentional and anonymous. The role of anonymity as a specific cyberbullying criterion has been stressed by several authors.14–16,21–23 Such studies have underlined the threatening nature of anonymity, but Nocentini et al.2 showed that although anonymity can raise insecurity and fear—if the perpetrator is familiar and he/she is someone who can be trusted—this can hurt the victim more. Overall, it seems that when anonymity is considered without any other criteria, it is perceived as more severe than when the act is done by a known person; at the same time when the act is anonymous and nonintentional, it is less representative of cyberbullying. Our results suggest that anonymity might change its impact on perception in relation to the other criteria and needs to be considered together with other criteria to be fully understood. Public versus private criterion did not show any relevance for the definition of cyberbullying; it seems that an act is defined as cyberbullying regardless of the fact that it is spread to a large audience or not. However, we cannot exclude that this criterion add something about the cyberbullying definition but at a lower level of relevance (i.e., as third dimension) or in combination with other criteria.

In terms of differences across types of behaviors, descriptive frequencies showed a more ambiguous role for exclusion as a form of cyberbullying, in line with traditional bullying literature.5,32 The other three types of behavior showed the same trend in terms of percentages of distribution. General support for the relevance of imbalance of power across all the types of behavior was found; intentionality (together with anonymity) is slightly more important in defining exclusion and impersonation than that of written-verbal and visual behaviors. However, given that differences are small we can assume structural equivalence of both dimensions across all the four types of behavior.†

In relation to the cross-country comparison, we need to underline some specificities related to the high frequencies of French participant's perceptions of the scenarios as cyberbullying, or cyberviolence; the French language does not have a direct translation of the term bullying and the term violence is generally used.5 Two possible explanations can help to understand these high frequencies of response. First, during 2010, a massive media campaign about school violence and cyberviolence was disseminated at the school level in France. Second, the term “cyberviolence” is very broad and can include a wider range of behaviors than the other terms used.5 In terms of the definition, general support for the relevance of imbalance of power was found across all the countries; intentionality (together with anonymity) is slightly less important in Italy and Germany as compared with the other countries. However, the differences are small, and are consistent with a structural equivalence of the second dimension across countries.

Finally, some limitations of the study have to be discussed, such as the randomized administration of the scenarios, the different terms used in each country, and the necessity of taking into account gender- and age-related differences.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1.

Presence (Y) or Absence (N) of the Criteria for all 32 Scenarios

| Scenarios | Intention | Repetition | Imbalance of power | Public/private | Anonymity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N | N | N | PRI | N |

| 2 | N | N | Y | PRI | N |

| 3 | Y | N | Y | PRI | N |

| 4 | N | Y | Y | PRI | N |

| 5 | Y | Y | Y | PRI | N |

| 6 | Y | N | N | PRI | N |

| 7 | N | Y | N | PRI | N |

| 8 | Y | Y | N | PRI | N |

| 9 | N | N | N | PUB | N |

| 10 | N | N | Y | PUB | N |

| 11 | Y | N | Y | PUB | N |

| 12 | N | Y | Y | PUB | N |

| 13 | Y | Y | Y | PUB | N |

| 14 | Y | N | N | PUB | N |

| 15 | N | Y | N | PUB | N |

| 16 | Y | Y | N | PUB | N |

| 17 | N | N | N | PUB | Y |

| 18 | N | N | Y | PUB | Y |

| 19 | Y | N | Y | PUB | Y |

| 20 | N | Y | Y | PUB | Y |

| 21 | Y | Y | Y | PUB | Y |

| 22 | Y | N | N | PUB | Y |

| 23 | N | Y | N | PUB | Y |

| 24 | Y | Y | N | PUB | Y |

| 25 | N | N | N | PRI | Y |

| 26 | N | N | Y | PRI | Y |

| 27 | Y | N | Y | PRI | Y |

| 28 | N | Y | Y | PRI | Y |

| 29 | Y | Y | Y | PRI | Y |

| 30 | Y | N | N | PRI | Y |

| 31 | N | Y | N | PRI | Y |

| 32 | Y | Y | N | PRI | Y |

Footnotes

All the data were weighted for a correction coefficient in order to reduce the ceiling effect of French data; the coefficient was based on the proportion between the percentages of all the countries divided by the percentages of the French data.

According to Sireci, Bastari, and Allalouf,33 structural equivalence does not hold when “one or more groups have weights near zero on a dimension and one or more other groups have large weights on the dimension” (p. 16).

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the European grant COST (Cooperation in Science and Technology) Action IS0801 “Cyberbullying: Coping with negative and enhancing positive uses of new technologies, in relationships in educational settings” for supporting this network.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Menesini E. Nocentini A. Cyberbullying definition and measurement: some critical considerations. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:230–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nocentini A. Calmaestra J. Schultze-Krumbholz A, et al. Cyberbullying: labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2010;20:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokunaga SR. Following you home from school: a critcal review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;26:277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith PK. Cyberbullying and cyber aggression. In: Jimerson RS, editor; Nickerson BA, editor; Mayer JM, editor; Furlong JM, editor. Handbook of school violence and school safety: international research and practice. New York: NY: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PK. Cowie H. Olafsson FR, et al. Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Development. 2002;73:1119–1133. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smorti A. Menesini E. Smith PK. Parents' definition of children's bullying in a five-country comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34:417–432. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulton M.J. Teachers' views on bullying: definitions, attitudes and ability to cope. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;67:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.1997.tb01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olweus D, editor. Bullying in school: what we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzer C. Cyberbullying in Germany: what has been done and what is going on. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:222–223. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q. New bottle but old wine: a research of cyberbullying in schools. Computers in Human Behavior. 2005;23:1777–1791. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith PK. Cyberbullying: abusive relationships in cyberspace. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:180–181. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandebosch H. Cleemput VK. Defining cyberbullying: a qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters. Cyberpsychology and Behavior. 2008;11:499–503. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigg WD. Cyber-Aggression: definition and concept of cyberbullying. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2010;20:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spears B. Slee P. Owens L, et al. Behind the scenes and screens: insights into the human dimension of covert and cyberbullying. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:189–196. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dooley JJ. Pyżalski J. Cross D. Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:182–188. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slonje R. Smith PK. Cyberbullying: another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2008;49:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaillancourt T. McDougall P. Hymel S, et al. Bullying: are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? International Journal of Behavioural Development. 2008;32:486–495. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith PK. Brain P. Bullying in schools: lessons from two decades of research. Aggressive behavior. 2000;26:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolak J. Mitchell K. Finkelhor D. Online victimization of youth: five years later. National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; Alexandria, VA: 2006. (CV138). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortega R. Elipe P. Mora-Merchán AJ, et al. The emotional impact on victims of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdur-Baker Ö. Cyberbullying and its correlation to traditional bullying, gender and frequent and risky usage of internet-mediated communication tools. New Media and Society. 2010;12:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishna F. Saini M. Solomon S. Ongoing and Online: children and youth's perception of cyber bullying. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:1222–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patchin WJ. Hinduja S. Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: a preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2006;4:148–169. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith PK. Mahdavi J. Carvalho M, et al. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finkelhor D. Mitchell JK. Wolak J. Online victimization: a report on the nation's youth. National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; Alexandria, VA: 2000. (CV138). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultze-Krumbholz A. Scheithauer H. Social-behavioral correlates of cyberbullying in a German student sample. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie/Journal of Psychology. 2009;217:224–226. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willard EN. Cyberbullying and cyberthreats: responding to the challange of online social aggression, threats, and distress. Illinois: Malloy, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menesini E. Nocentini A. Calussi P. The measurement of cyberbullying: dimensional structure and relative item severity and discrimination. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2011;14:267–274. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berne S. Frisen A. Adolescents' view on how different criteria define cyberbullying. ECDP conference; 2011 Aug 23–27; Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borg I. Groenen PJF. Modern multidimensional scaling. 2nd. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruskal JB. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrics. 1964;29:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menesini E. Fonzi A. Smith PK. Attribution of meanings to terms related bullying: a comparison between teacher's and pupil's perspectives in Italy. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2002;17:393–406. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sireci SG. Bastari B. Allalouf A. Evaluating construct equivalence across adapted tests. Retrieved from ERIC database 1998. www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED428120.pdf www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED428120.pdf (ED 428120)