Abstract

Two approaches to high-resolution SENSE-encoded magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) of the human brain at 7 Tesla (T) with whole-slice coverage are described. Both sequences use high-bandwidth radiofrequency pulses to reduce chemical shift displacement artifacts, SENSE-encoding to reduce scan time, and dual-band water and lipid suppression optimized for 7T. Simultaneous B0 and transmit B1 mapping was also used for both sequences to optimize field homogeneity using high order shimming and determine optimum radiofrequency (RF) transmit level, respectively. One sequence (‘Hahn-MRSI’) used reduced flip angle (90°) refocusing pulses for lower RF power deposition, while the other sequence used adiabatic fast passage (AFP) refocusing pulses for improved sensitivity and reduced signal dependence on the transmit-B1 level. In 4 normal subjects, AFP-MRSI showed a signal-to-noise ratio improvement of 3.2±0.5 compared to Hahn-MRSI at the same spatial resolution, TR, TE and SENSE-acceleration factor. An interleaved two-slice Hahn-MRSI sequence is also demonstrated to be experimentally feasible.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, spectroscopic imaging, 7 Tesla, sensitivity-encoding, dual-band suppression, brain, adiabatic pulses

INTRODUCTION

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) at 7.0T have been shown to offer a number of advantages over scans performed at lower field strengths. These include higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), better spectral resolution, and the ability to accurately determine the concentrations of a larger number of compounds than is possible at either 1.5 or 3.0T (1–12). For instance, Tkac et al. showed that it is possible to determine the concentrations of up to 17 different compounds using short echo time single voxel (SV) MRS at 7.0T (13), and in the occipital lobe SNR was increased by a factor or 2 at 7.0T compared to 4.0T using half-volume transmit-receive coils (13). Similarly, a slice-selective echo-planar spectroscopic imaging (EPSI) study found that SNR increased almost linearly with field strength between 1.5 and 7.0T in vivo for central brain regions using a volume transmit-receive coil (14).

While single voxel MRS is well established at 7.0T (1, 15, 13, 12), MRSI at 7.0T still inspires frequent efforts for improvements and innovations, particularly in areas related to inhomogeneities in B0 and B1 fields over the volume of the brain, and other issues such as chemical shift displacement (CSD) errors, and radiofrequency power deposition (specific absorption rate (SAR)), which are all increased at 7.0T compared to lower field strengths (16). Metabolite T2 and T2* relaxation times are also shorter than at lower field (1). Previous MRSI studies at 7.0T have used PRESS (17, 2, 5), SSFP (4) or semi-LASER (3) volume-excitation, or single-slice approaches (6, 7, 9). Increasing brain coverage while maintaining high spatial resolution can also lead to long scan times, particularly if long TR values are used to minimize T1-weighting and SAR.

Recently, several approaches to these problems have been described (18–20). For instance, one study has shown that excellent field homogeneity can be obtained at 7T through the use of strong, high order B0 shim currents up to 4th order (20). Another recent paper describes a multi-slice sequence using an 8-element multi-transmit system, as well as dynamic B0 and B1 shimming (18) with an FID-based acquisition that includes a broadband acquisition sequence which has minimal chemical shift dispersion errors. The absence of a refocusing pulse significantly reduces RF power requirements but does lead to first order phase errors in the spectrum, as has been described previously (7). One approach to this problem is to incorporate the first order phase-error into the basis set functions that are used for the spectral fitting routines (19).

In this paper, two pulse-sequences for high resolution MRSI at 7.0T which are based on spin echo acquisitions (and which therefore have minimal first order phase errors) are described and compared. Both sequences have whole-slice coverage, dual-band water and lipid suppression optimized for 7.0T, SENSE-encoding to reduce scan times, and high-bandwidth frequency modulated slice-selective pulses to minimize CSD errors. SENSE-accelerated MRSI at high magnetic field strengths has previously been demonstrated (21–24). One sequence uses reduced flip-angle refocusing pulses which have lower SAR and allow for increased coverage, while the other sequence uses B1-insensitive adiabatic fast passage (AFP) refocusing pulses which have higher SAR (limiting coverage to a single-slice at present), but give higher SNR and more uniform metabolic images since the AFP pulses are insensitive to transmit B1 inhomogeneity.

Materials and Methods

Pulse Sequence Design

The basic structure of both pulse sequences is a slice-selective spin-echo sequence with two-dimensional phase-encoding, water and outer-volume (OVS) lipid suppression as originally described by Duyn et. al at 1.5T (25). This sequence has previously been modified for use at 3.0T with SENSE-encoding (24) to reduce scan time, and an optimized dual-band water and lipid suppression sequence (26). In this paper, this sequence is further modified for use at 7.0T in the following ways: (1) optimization of the dual-band water and lipid suppression for 7.0T, (2) two different refocusing pulse options either for multi-slice coverage or high SNR single-slice data, (3) decreased TE values to minimize T2-weighting, (4) reconstruction of metabolic images to account for transmit B1-inhomogeneity. (5) simultaneous B0 and B1 mapping to optimize field homogeneity and RF transmit level (27).

Slice-Selection

Two pulse sequences were developed and compared (Figure 1A and B)). In both sequences, slice selective excitation was achieved by a frequency modulated 90° pulse (‘fremex05’) with a duration of 8.7 ms and a bandwidth of 4.7 kHz (28), requiring a peak B1 of 13.5 μT (system peak B1 is 15 μT). In sequence (A), the same pulse was also used for refocusing (i.e. a 90°-90° echo, as originally described by Hahn (29)), while in sequence (B) refocusing in the same plane was achieved by a pair of adiabatic fast passage (AFP) 180° pulses with a duration of 7 msec and a bandwidth and sweep of 4.7 kHz (30). For sequence (A), the minimum TE was 19 msec, while for sequence (B) the minimum TE value was 29 msec due to the duration of the RF and gradient pulses used.

Figure 1.

Pulse sequences developed for slice-selective MRSI at 7T. (A) Hahn-MRSI (90°-90°), (B) AFP-MRSI (90°-180°-180°) sequences. In both cases, signal excitation is preceded by (C) a dual-band water and lipid suppression with integrated outer-volume suppression (OVS).

Water and Lipid Suppression

A 5-pulse dual-band sequence with integrated OVS has been previously described for use with SENSE-MRSI at 3.0T (26). This sequence was re-optimized for use at 7.0T taking the following considerations into account: the longer T1-relaxation times of water and lipid at 7.0T (31), the greater frequency difference (measured in Hz) between water and lipid at 7.0T, and the need to minimize sequence SAR at 7.0T compared to lower field strengths. Optimization procedures were performed as described previously in reference (26).

The result of the optimization is illustrated in figure 1C. The sequence consists of 3 dual-band pulses and a set of 8 OVS pulses placed between the 2nd and 3rd dual-band pulses. Each dual-band pulse has a duration of 40 ms and consists of the sum of two asymmetric frequency-modulated pulses that suppress water and lipid resonances respectively. The passband was between 4.1 ppm and 1.8 ppm, and the approximate bandwidth of the water and lipid stop bands were 0.8 ppm and 1.0 ppm respectively. Each OVS pulse had a duration of 2.86 msec and a bandwidth of 2.9 kHz, followed by a gradient crusher of 3 ms duration and 18 mT/m amplitude.

Experiments

Experiments were performed on 4 normal volunteers (1 female, ages 41+14 years) on a 7.0T Achieva system (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) equipped with a 32-channel phased receive array and quadrature transmit coil (Nova Medical, Orlando, FL). The nominal peak B1 of the transmit coil was 15 uT. Written informed consent was obtained after local institutional review board approval.

After collection of localizer images and receiver coil sensitivity maps, a single 15 mm thick axial slice above the level of the lateral ventricles was identified. A rapid combined B0 and B1 field mapping technique was used to optimize B0 homogeneity using 2nd order shim correction, and to determine the optimal transmit B1 level at the location of the MRSI excitation volume (23). The following scans were then performed: MRSI with sequence A (‘Hahn-MRSI’) and sequence B (‘AFP-MRSI’), as well as an AFP-MRSI scan without dual-band suppression (‘H2O-MRSI’). An additional transmit B1 field map (27) was also measured at the same slice location, thickness, and radiofrequency drive scale as the MRSI slice which was used for post-processing B1 correction of the MRSI data. Parameters for each pulse sequence are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pulse Sequence Parameters

| Hahn-MRSI | AFP-MRSI | H2O-MRSI | B1 map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (mm) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| FOV (mm) | 210 × 190 | 210 × 190 | 210 × 190 | 210 × 190 |

| Matrix Size | 29×27 | 29×27 | 29×27 | 64×54 |

| Voxel Size (cm3) | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | - |

| SENSE Factor | 2×2 | 2×2 | 3×2 | - |

| TR: TE (msec) | 4500: 29 | 4500: 29 | 3500: 29 | 100, 140: 1.7 |

| Flip Angle (°) | 90-90 | 90-180-180 | 90-180-180 | 50 |

| #Points/Spectral Width | 4096/5 kHz | 4096/5 kHz | 4096/5 kHz | - |

| Scan Time | 12:27 min | 12:27 min | 6:29 min | 0:52 min |

| % SAR* | 24 | 53 | 53 | 57 |

SAR value expressed as a percentage of the FDA limit of 3.2 W/kg averaged over 10 minutes for head imaging.

In one subject, a 2-slice Hahn-MRSI scan was recorded with identical parameters to Table 1, except that the TR was reduced to 3.5 sec and the SENSE factor was 1.5×1.5 (= 2.25). Scan time was 17:30 for the 2-slice acquisition and SAR was 54%, comparable to a 1-slice acquisition of the AFP-MRSI sequence. The lower slice was placed at the level of the centrum semiovale and the upper slice covered mainly cortical gray matter. Shimming and RF transmit parameters for the 2-slice Hahn-MRSI acquisition were optimized over the whole volume of both slices, as dynamic shimming and adjustment of B1 transmit level on a slice-by-slice basis were not available. Hardware average power monitoring restrictions over the duration of the MRSI scan limited maximum SAR to about 60% in these experiments.

Data processing and metabolic image reconstruction

SENSE-MRSI reconstruction, including channel-combination, was performed by the scanner software. Reconstructed, time-domain MRSI data was then exported from the scanner for further spectral processing using MATLAB (Mathworks, MA). 4 Hz exponential line-broadening and Fourier transformation were first applied to all MRSI results (H20, AFP and Hahn). Each voxel was corrected for eddy-currents, phase error and frequency shift using the water peak at 4.68 ppm in the H20-MRSI scan using a fully automated routine. The phase and frequency values extracted from the H2O-MRSI scan were then applied to AFP-MRSI or Hahn-MRSI on a voxel-by-voxel basis. It was found that the phase-correction values determined from the H2O-MRSI scan were able to successfully phase-correct both the AFP-MRSI and Hahn-MRSI spectra, indicating that the spatially-dependent phase (and frequency) variations were the same in all 3 acquisitions. Spectra were analyzed using the VeSPA program (38) using baseline correction and simulated basis sets for each pulse sequence. Cramer-Rao lower bounds (CRLB) were estimated for each metabolite in each voxel. Metabolite images were normalized relative to the water signal from the same slice, in order to minimize intensity variations due to B1 inhomogeneity.

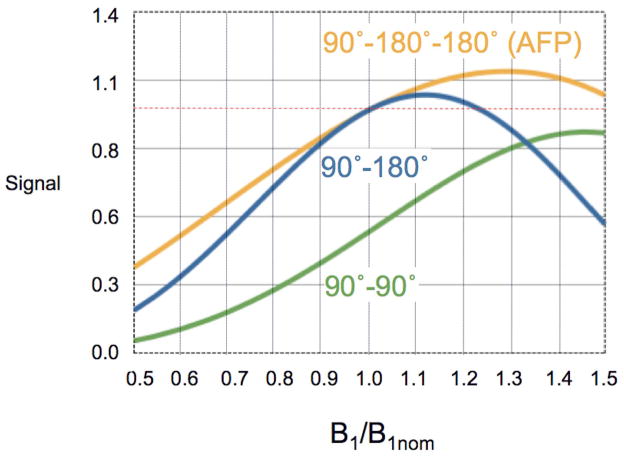

If the dual AFP-refocusing pulses are working in the adiabatic limit, they are expected to be B1 insensitive, however the non-adiabatic excitation pulse will have a sin(α) dependence, and the SENSE-reconstruction (based on receive coil sensitivity profiles normalized to the transmit B1 coil) will also have a linear dependence on the transmit B1. In contrast. in the Hahn-MRSI scan, there is a sin2(α/2) signal dependence associated with the refocusing pulse. The overall correction factors are therefore 1/(B1 sin(α)) and 1/(B1 sin(α) sin2(α/2)) for AFP- and Hahn-MRSI sequences respectively. The expected signal intensities as a function of B1 are shown in Figure 2 for both the AFP- and Hahn-MRSI scans. The signal intensity for a conventional (non-adiabatic) 90°- 180° spin echo sequence is included as well for comparison. Note that in these simple calculations the effects of relaxation and off-resonance effects are ignored.

Figure 2.

Theoretical signal dependence of the 90°-90° (B1×sin(α)×sin2(α/2)) and 90°-AFP (B1×sin(α)) sequences as a function of the transmit B1 field relative to a nominal B1 field corresponding to a 90° rotation. Off-resonance effects and the effects of relaxation are ignored in these simulations. For comparison, the B1 dependence of a conventional 90°-180° spin echo sequence (B1×sin3(α)) is also shown.

Finally, for comparing the Hahn and AFP-MRSI scans, the average SNR of the central 8×7 voxels was calculated. SNR was defined as the peak height of NAA divided by twice the root-mean-square noise level between 8 and 10 ppm, where no signals are expected.

Results

For the frequency modulated 90° pulse and the AFP refocusing pulses used here, the 4.7 kHz bandwidth corresponds to a chemical shift displacement of 6%/ppm, so, for instance, the relative difference in location of the mI and NAA slices (separated by 1.6 ppm) is ~10%, or 1.5 mm for a 15 mm slice thickness. Therefore, the use of these high-bandwidth frequency modulated pulses largely overcomes CSD artifacts at 7T. In-plane CSD is avoided in these experiments by the use of 2D phase-encoding and spin-echo excitation.

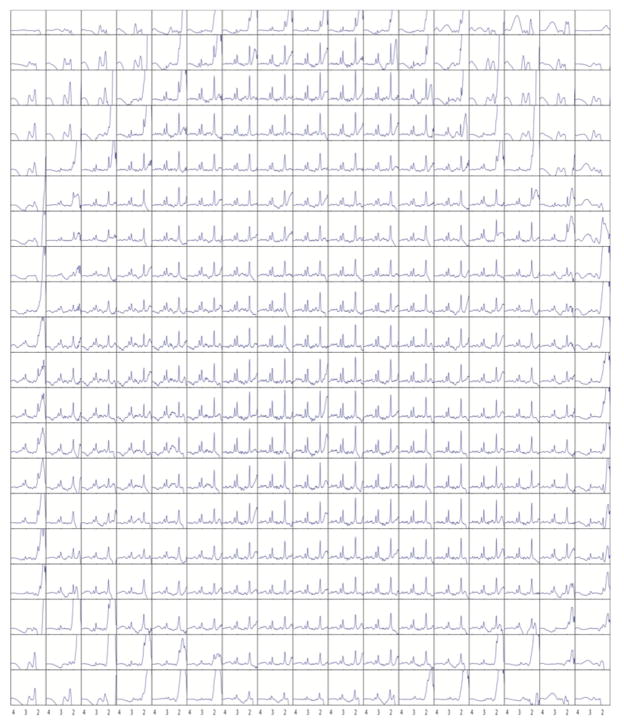

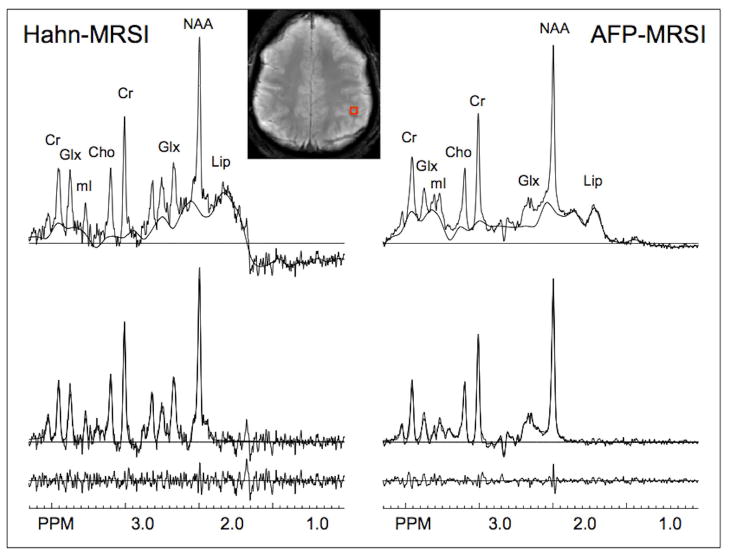

Figure 3 shows metabolic images from one subject, including structural MRI, B1-map, and normalized metabolic images of glutamate and glutamine (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr) and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) recorded using the AFP-MRSI sequence. Figure 4 shows spectra from the entire slice of the AFP-MRSI data in figure 3. A comparison of spectra recorded from the left parietal gray matter using Hahn-MRSI and AFP-MRSI is shown in Figure 5. The AFP-MRSI sequence has a significantly larger signal in this example. Over all the central region of the MRSI slice in all subjects, the Hahn-MRSI sequence had an average SNR of 50±17, while for the AFP-MRSI sequence the SNR was 156±29. For the AFP-MRSI sequence, average CRLB’s over the whole slice (excluding pixels at the very edges of the brain) were as follows: Cho 3.4±3.3 (%, mean ± st.dev), Cr 1.2±0.3, Glx 1.4 ± 0.3, mI 1.3 ±0.3 and NAA 0.9 ± 0.2. Consistent with its lower SNR ratio, for the Hahn-MRSI sequence the CRLB’s were: Cho 7.1±4.2 (%, mean ± st.dev), Cr 4.9±1.8, Glx 3.6 ± 1.5, mI 8.7 ±4.4 and NAA 2.6 ± 0.8.

Figure 3.

Metabolic images recorded using the AFP-MRSI sequence in one subject. In addition to the sagittal (showing MRSI slice location) and axial anatomical MR images, the transmit B1 map, and reconstructed metabolic images of images of glutamate and glutamine (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr) and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) normalized to the H2O-MRSI are shown. Histograms of the transmit B1 distribution and the frequency (B0) distribution after high order shimming in this slice location are also shown. 59% of MRSI voxels fell within the range +/− 10 Hz.

Figure 4.

AFP-MRSI spectra from the whole slice of the dataset as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 5.

Comparison of spectra using the Hahn-MRSI and AFP-MRSI pulse sequences in the same voxel (left parietal gray matter) from one subject; top trace is the original spectra and baseline fit, middle trace the baseline-subtracted experimental data overlaid with the results of the fitting routine, and the bottom trace the residual. The approximately 3-fold greater SNR of the AFP-MRSI sequence under the same acquisition conditions is apparent. However, the SAR of the AFP-MRSI sequence was more than double that of the Hahn-MRSI sequence (53% vs. 24%, respectively). Mild residual lipid (Lip) contamination is present.

Figure 6 shows a grid plot from one slice of the 2-slice MRSI data from the one subject recorded using the Hahn-MRSI sequence. For this 2-slice Hahn-MRSI data with a reduced SENSE acceleration factor of 1.5×1.5, SNR of the central 8×7 voxels was 93±24 for the lower slice and 63±19 for the upper slice.

Figure 6.

Hahn-MRSI spectra from one slice of the 2-slice dataset recorded in one subject. In these experiments, note the incomplete lipid unfolding upfield from the NAA peak in central voxels, due to errors in the SENSE-reconstruction algorithm used.

Discussion

In this paper, two approaches to SENSE-encoded 2D MRSI at 7T of the human brain are described. In both cases, the number of slices and the minimum TR that could be used was limited by the sequence SAR; by using a 90° refocusing pulse, two slices could be interleaved without exceeding the maximum allowed SAR. In contrast, the AFP sequence had significantly higher SAR and so could only be used in a single-slice mode; however, the AFP sequence had significantly higher SNR because of its more efficient refocusing and lower sensitivity to variations in the transmit B1 level, providing more uniform metabolic images.

B1 homogeneity may be improved by the use of multiple transmit coils and ‘B1 shimming’ (32), and has previously been demonstrated for MRS and MRSI at 7T (9, 12). Multi-transmit also allows the option of tailoring the B1 profile differently for different parts of the pulse sequence. For instance, for lipid suppression, it was shown that an 8-transmit element coil array can be driven to produce a B1 field in a ‘ring mode’ where the highest B1 intensity corresponds to the location of the scalp, thereby allowing high B1 intensity for lipid suppression while at the same time minimally affecting the magnetization (and power deposition) within the brain (18, 9). In the same pulse sequence the excitation pulses for the brain are applied in a relatively homogenous mode. The results presented here suggest that the current dual-band suppression methodology (applied with a quadrature transmit coil) can provide acceptable lipid suppression performance within FDA-allowed SAR limits, even when multi-channel transmit/B1 shimming is not available.

Adiabatic pulses have previously been used for 7T MRSI (17, 3). Typically, adiabatic pulses offer advantages over conventional, amplitude modulated RF pulses in terms of improved slice profiles, higher bandwidths, and insensitivity to inhomogeneities in the B1 field. For refocusing, pairs of adiabatic 180° pulses have to be used in order to compensate for the nonlinear phase-error associated with individual adiabatic pulses (33). The fully adiabatic LASER sequence uses in total 7 adiabatic pulses (33), including 6 adiabatic 180° pulses, which results in high SAR values. Therefore, one implementation of 7T MRSI used instead the semi-LASER experiment which had a conventional slice-selective 90° excitation pulse and 4 adiabatic 180’s (3). The current AFP-MRSI sequence further reduces the number of adiabatic 180° pulses to 2, lowering SAR, and also has whole-slice coverage (unlike LASER or semi-LASER). Although the sequence is not fully-adiabatic, B1 mapping allows for post-hoc correction of metabolite signal intensities to account for the variations in the excitation pulse flip angle and receive sensitivity. Figure 2 shows the expected improved SNR performance of the AFP-MRSI sequence compared to non-adiabatic 90°-90° or 90°-180° sequences. At B1 level corresponding to the nominal 90° flip angle, the AFP-MRSI sequence should provide double SNR compared to the Hahn-MRSI sequence. If the B1 level is reduced corresponding to a flip angle of 70°, the AFP-sequence offers an SNR improvement of 3.07, very similar to the 3.12 improvement measured experimentally; note that the average flip angle over the MRSI slice was lower than 90° in these experiments, since the flip angle calibration procedure was performed on the center of the slice where B1 is higher than in peripheral regions. For adiabatic pulses to be insensitive to variations in B1, the pulses must fulfill the ‘adiabatic condition’, namely that |dθ/dt| ≪ ωeff = γBeff, where θ is the angle between the magnetization and the B0 magnetic field, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, and Beff is the effective field in the rotating reference frame. A measure of adiabacity can be expressed Q = ωeff/(dθ/dt), where Q ≥ 1 indicates the pulse should have adiabatic characteristics (30). When determining suitable pulses for AFP-MRSI at 7T, several factors need to be considered. A major factor is the length of the pulse, since longer RF pulses (i.e. slower dθ/dt) will be more adiabatic but also have higher SAR. Another consideration is that the minimum B1 level over the region to be covered by MRSI may be significantly lower than the nominal B1 field, and therefore, for ideal performance, Q should be determined for the lowest B1 level likely encountered. Finally, the optimal amplitude/frequency waveforms of the pulse itself need to be considered. In the current form, the waveform proposed by Rosenfeld (30) was chosen because of its reported improved efficiency compared to the commonly used hyperbolic secant. Calculations indicated that the average Q factor for this pulse will be around 1 for a 7 msec duration and a B1 value of 10 uT (i.e less than the nominal 15 uT), indicating it to be suitable to use in the current experiments. For lower B1 values, a longer pulse would be required for adiabatic performance to be maintained.

Other investigators have also demonstrated alternative approaches to 7T-MRSI, either using no refocusing pulses at all (7, 11) or numerically-designed spectral-spatial refocusing pulses (17). The absence of refocusing pulses is attractive in that SAR is low and very short TE values can be obtained. However, as mentioned above, potential drawbacks of this approach are the large 1st-order phase errors caused by the delay between excitation and acquisition, often causing baseline artifacts in the spectrum, and (at very short TE) the increased contribution of macromolecules to the spectrum. Both of these problems can be potentially overcome by the use of time-domain fitting approaches (34), but fitting of these data is more difficult than compared to that of spectra without phase-errors, and with less macromolecule contamination. The use of spectral-spatial refocusing (17) has a number of advantages, including lower peak power, adiabatic performance and removal of unwanted water and lipid signals, but does also have some drawbacks, including the use of very long pulses (e.g 30 msec) which limit the minimum TE that can be achieved, and also potentially limited spectral width. For instance, in reference (17)), Cho and Cr were acquired in separate experiments to NAA because of excitation bandwidth limitations of the spectral-spatial pulses.

In the current experiments, relatively long TR values had to be used in both sequences because of SAR limitations. While this results in less T1-weighting, it also implies that very long scan times would have been required if conventional phase-encoding were used. In the current experiments, SENSE-acceleration factors (21) of 4 (2 in each phase-encode direction) were used for the scans with water/lipid suppression, and a factor of 6 for the water reference MRSI; without SENSE acceleration these scans would have lasted for more than 50 minutes. Other ways to decrease scan time in MRSI experiments include the use of an echo-planar spectroscopic imaging (EPSI) readout, which has also previously been demonstrated at 7T (14). Such an approach does require fast-switching of the EPSI readout, however, because of the higher spectral width (measured in Hz) required at 7T compared to lower field strengths.

The metabolite images presented images presented in figures 3 and 6 contain some artifactual hyper- and hypo-intensities which are probably due to errors in baseline correction, SENSE reconstruction, and residual water and lipid signals. In the future, each of these areas could be addressed and improved upon; for instance, more sophisticated methods of peak area determination and baseline correction could be used (35), as well as improved methods of SENSE reconstruction (36, 37). The classical SENSE reconstruction algorithm used in this manuscript assumes that the sensitivity profile of the receiver coils does not change across each MRSI voxel; this may be a poor approximation when using relatively large MRSI voxels, and therefore lead to unfolding errors. These errors are most noticeable for the strong peri-cranial lipid signals which foldover into the brain (e.g. see figure 6). These lipid signals are artifacts and preclude the observation of compounds in this region of the spectrum such as lactate or alanine. This is a limitation of the methods proposed here. In the future more sophisticated reconstruction algorithms might be used to address this problem (36, 37). Post-hoc B1 correction could also be modified to include the effects of T1 relaxation times. The lipid suppression component of the dualband sequence was designed to be reasonably tolerant to variations in B1, with simulated residual lipid signals of < 5% over a range of B1 from 60 to 125% of nominal. The previously published dualband sequence for use at 3T (26) had somewhat better performance, but at the expense of higher SAR.

In summary, two approaches to high-resolution SENSE-MRSI of the human brain are described at 7T using a 32-channel receive array. The sequences feature whole-slice coverage, high SENSE acceleration factors, minimal CSD artifacts, dual-band water and lipid suppression, and (in the case of the AFP-MRSI sequence) insensitivity to transmit B1 inhomogeneity. Future work is needed to further reduce SAR and allow for extension to greater coverage (e.g. whole-brain (35)) coverage, perhaps using 3D-SENSE-MRSI approaches.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by NIH grants P41RR15241 and R21MH082322. We thank Dr James Murdoch for excellent technical support and Dr Richard Edden for useful discussions. Early development work on these sequences was performed at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, where we thank Dr John Gore, Dr Calum Avison and Dr Brian Welch for scanner access and technical support.

References

- 1.Tkac I, Andersen P, Adriany G, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the human brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2001 Sep;46(3):451–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balchandani P, Spielman D. Fat suppression for 1H MRSI at 7T using spectrally selective adiabatic inversion recovery. Magn Reson Med. 2008 May;59(5):980–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheenen TW, Heerschap A, Klomp DW. Towards 1H-MRSI of the human brain at 7T with slice-selective adiabatic refocusing pulses. MAGMA. 2008 Mar;21(1–2):95–101. doi: 10.1007/s10334-007-0094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuster C, Dreher W, Stadler J, Bernarding J, Leibfritz D. Fast three-dimensional 1H MR spectroscopic imaging at 7 Tesla using “spectroscopic missing pulse--SSFP”. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Nov;60(5):1243–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu D, Cunningham CH, Chen AP, Li Y, Kelley DA, Mukherjee P, Pauly JM, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB. Phased array 3D MR spectroscopic imaging of the brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008 Nov;26(9):1201–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avdievich NI, Pan JW, Baehring JM, Spencer DD, Hetherington HP. Short echo spectroscopic imaging of the human brain at 7T using transceiver arrays. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Jul;62(1):17–25. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henning A, Fuchs A, Murdoch JB, Boesiger P. Slice-selective FID acquisition, localized by outer volume suppression (FIDLOVS) for (1)H-MRSI of the human brain at 7 T with minimal signal loss. NMR Biomed. 2009 Aug;22(7):683–96. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi C, Ghose S, Uh J, Patel A, Dimitrov IE, Lu H, Douglas D, Ganji S. Measurement of N-acetylaspartylglutamate in the human frontal brain by 1H-MRS at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Nov;64(5):1247–51. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hetherington HP, Avdievich NI, Kuznetsov AM, Pan JW. RF shimming for spectroscopic localization in the human brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Jan;63(1):9–19. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan JW, Avdievich N, Hetherington HP. J-refocused coherence transfer spectroscopic imaging at 7 T in human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Nov;64(5):1237–46. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boer VO, Siero JC, Hoogduin H, van Gorp JS, Luijten PR, Klomp DW. High-field MRS of the human brain at short TE and TR. NMR Biomed. 2011 Nov;24(9):1081–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boer VO, van Lier AL, Hoogduin JM, Wijnen JP, Luijten PR, Klomp DW. 7-T (1) H MRS with adiabatic refocusing at short TE using radiofrequency focusing with a dual-channel volume transmit coil. NMR Biomed. 2011 Nov;24(9):1038–46. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tkac I, Oz G, Adriany G, Ugurbil K, Gruetter R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the human brain at high magnetic fields: metabolite quantification at 4T vs. 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Oct;62(4):868–79. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otazo R, Mueller B, Ugurbil K, Wald L, Posse S. Signal-to-noise ratio and spectral linewidth improvements between 1.5 and 7 Tesla in proton echo-planar spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Dec;56(6):1200–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mekle R, Mlynarik V, Gambarota G, Hergt M, Krueger G, Gruetter R. MR spectroscopy of the human brain with enhanced signal intensity at ultrashort echo times on a clinical platform at 3T and 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Jun;61(6):1279–85. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaughan JT, Garwood M, Collins CM, Liu W, DelaBarre L, Adriany G, Andersen P, Merkle H, Goebel R, Smith MB, Ugurbil K. 7T vs. 4T: RF power, homogeneity, and signal-to-noise comparison in head images. Magn Reson Med. 2001 Jul;46(1):24–30. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balchandani P, Pauly J, Spielman D. Interleaved narrow-band PRESS sequence with adiabatic spatial-spectral refocusing pulses for 1H MRSI at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2008 May;59(5):973–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boer VO, Klomp DW, Juchem C, Luijten PR, de Graaf RA. Multislice (1) H MRSI of the human brain at 7 T using dynamic B(0) and B(1) shimming. Magn Reson Med. 2012 doi: 10.1002/mrm.23288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogner W, Gruber S, Trattnig S, Chmelik M. High-resolution mapping of human brain metabolites by free induction decay (1) H MRSI at 7 T. NMR Biomed. 2012 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan JW, Lo KM, Hetherington HP. Role of very high order and degree B(0) shimming for spectroscopic imaging of the human brain at 7 tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2012 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dydak U, Weiger M, Pruessmann KP, Meier D, Boesiger P. Sensitivity-encoded spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46(4):713–22. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin FH, Tsai SY, Otazo R, Caprihan A, Wald LL, Belliveau JW, Posse S. Sensitivity-encoded (SENSE) proton echo-planar spectroscopic imaging (PEPSI) in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007 Feb;57(2):249–57. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otazo R, Tsai SY, Lin FH, Posse S. Accelerated short-TE 3D proton echo-planar spectroscopic imaging using 2D-SENSE with a 32-channel array coil. Magn Reson Med. 2007 Dec;58(6):1107–16. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonekamp D, Smith MA, Zhu H, Barker PB. Quantitative SENSE-MRSI of the human brain. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010 Apr;28(3):305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duyn JH, Gillen J, Sobering G, van Zijl PCM, Moonen CTW. Multislice Proton MR Spectroscopic Imaging of the Brain. Radiology. 1993;188(1):277–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.1.8511313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Ouwerkerk R, Barker PB. Dual-band water and lipid suppression for MR spectroscopic imaging at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Jun;63(6):1486–92. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schar M, Vonken EJ, Stuber M. Simultaneous B(0)- and B(1)+-map acquisition for fast localized shim, frequency, and RF power determination in the heart at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Feb;63(2):419–26. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murdoch JB, editor. Still iterating... and iterating.. to solve pulse design problems; 10th ISMRM Scientific Meeting; 2002; Hawai’i. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hahn EL. Spin Echoes. Phys Rev. 1950;80(4):580–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenfeld D, Zur Y. A New Adiabatic Inversion Pulse. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:124–38. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rooney WD, Johnson G, Li X, Cohen ER, Kim SG, Ugurbil K, Springer CS. Magnetic field and tissue dependencies of human brain longitudinal 1H2O relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:308–18. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adriany G, Van de Moortele PF, Wiesinger F, Moeller S, Strupp JP, Andersen P, Snyder C, Zhang X, Chen W, Pruessmann KP, Boesiger P, Vaughan T, Ugurbil K. Transmit and receive transmission line arrays for 7 Tesla parallel imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005 Feb;53(2):434–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garwood M, DelaBarre L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J Magn Reson. 2001 Dec;153(2):155–77. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanhamme L, Sundin T, Hecke PV, Huffel SV. MR spectroscopy quantitation: a review of time-domain methods. NMR Biomed. 2001 Jun;14(4):233–46. doi: 10.1002/nbm.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maudsley AA, Darkazanli A, Alger JR, Hall LO, Schuff N, Studholme C, Yu Y, Ebel A, Frew A, Goldgof D, Gu Y, Pagare R, Rousseau F, Sivasankaran K, Soher BJ, Weber P, Young K, Zhu X. Comprehensive processing, display and analysis for in vivo MR spectroscopic imaging. NMR Biomed. 2006 Jun;19(4):492–503. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Gonzalez J, Tsao J, Dydak U, Desco M, Boesiger P, Pruessmann KP. Minimum-norm reconstruction for sensitivity-encoded magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Feb;55(2):287–95. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otazo R, Lin FH, Wiggins G, Jordan R, Sodickson D, Posse S. Superresolution parallel magnetic resonance imaging: application to functional and spectroscopic imaging. Neuroimage. 2009 Aug 1;47(1):220–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soher BJ, Semanchuk P, Todd D, Steinberg J, Young K. VeSPA: Integrated applications for RF pulse design, spectral simulation and MRS data analysis. ISMRM; 2011; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. p. 1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]