Abstract

Phytoestrogens, estrogenic compounds derived from plants, are ubiquitous in human and animal diets. These chemicals are generally much less potent than estradiol but act via similar mechanisms. The most common source of phytoestrogen exposure to humans is soybean-derived foods that are rich in the isoflavones genistein and daidzein. These isoflavones are also found at relatively high levels in soy-based infant formulas. Phytoestrogens have been promoted as healthy alternatives to synthetic estrogens and are found in many dietary supplements. The aim of this review is to examine the evidence that phytoestrogen exposure, particularly in developmentally sensitive periods of life, has consequences for future reproductive health.

Keywords: genistein, soy, reproductive tract, fertility, preimplantation embryo

Introduction

Phytoestrogens are plant compounds that are structurally similar to estradiol and can interact with estrogen receptors to promote and/or inhibit estrogenic responses. These compounds are ingested as part of a normal diet and are frequently included in plant-based dietary supplements such as those advertised to alleviate symptoms of menopause. The major phytoestrogen groups are isoflavones (genistein, daidzein, glycitein, formononetin), flavones (luteolin), coumestans (coumestrol), stilbenes (resveratrol) and lignans (secoisolariciresinol, matairesinol, pinoresinol, lariciresinol) (Moutsatsou 2007). Isoflavones are found at high concentrations in soybean products whereas lignans are found in flax seed, coumestans are found in clover, and stilbenes are found in cocoa- and grape-containing products, particularly red wine. The β-D-glycoside form of genistein, genistin, makes up the majority (55–65%) of the isoflavone content of soy products (Setchell et al. 1997). The β-D-glycoside form of daidzein, daidzin, comprises about 30–35%, and glycitin, glycitein, biochanin A and formononetin together account for <10% of soy isoflavones. For additional reference regarding dietary isoflavone content, see the USDA-Iowa State University Database on the Isoflavone Content of Foods (release 1.3, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD) at http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/isoflav/isoflav.html and Thompson et al. (Thompson et al. 2006).

Observational studies several decades ago raised concerns regarding reproductive toxicity of phytoestrogens consumed in the diet. The earliest evidence that naturally occurring phytoestrogens could cause reproductive disturbances in mammals was a report in 1946 indicating that sheep grazing on red clover were infertile due to the estrogenic content of the clover (Bennetts et al. 1946; Morley et al. 1966). About 20 years later, a similar observation was made in cows that had fertility disturbances resulting from periods of stall-feeding on red clover (Kallela et al. 1984). Last, a population of captive cheetahs exhibited infertility while eating soy-based diets (Setchell et al. 1987). In all three cases, fertility was restored when the phytoestrogen intake was reduced. Similarly, abnormalities in reproductive health due to high intake of soy products have been reported in several women (Amsterdam et al. 2005; Chandrareddy et al. 2008). These observations demonstrate that dietary phytoestrogens can have adverse effects on reproductive function in adults.

Organ systems in developing animals are typically more sensitive to chemical exposures than adults; the developing reproductive system is no exception. In fact, extensive tissue morphogenesis and differentiation of organs important for reproductive function occurs both pre- and postnatally. Many of these differentiation events are dependent at least in part on steroid hormone signaling (Ma 2009; MacLusky & Naftolin 1981; Park & Jameson 2005; Sakuma 2009; Young et al. 1964). For this reason, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including phytoestrogens, could have a significant impact on development in ways that affect later reproductive health. Furthermore, these effects could have long-term consequences for the offspring of the affected individuals.

Since the initial observations of adverse effects of phytoestrogens on adult mammalian reproductive health, numerous studies have been performed in laboratory animal models to evaluate the estrogenic activity of phytoestrogens (Diel et al. 2000; Jefferson et al. 2002) and their effects on development and reproduction. Most studies have been performed in rodent models, with various phytoestrogens administered either prenatally to the pregnant dam or postnatally to the pups (Bateman & Patisaul 2008; Burroughs et al. 1990b; Jefferson et al. 2005; Kouki et al. 2003; Medlock et al. 1995b; Nagao et al. 2001; Newbold et al. 2001; Nikaido et al. 2004). Together, these studies provide a wealth of evidence that exposure of developing animals to phytoestrogens negatively impacts future fertility. We present here background information regarding human phytoestrogen exposure that provides the rationale for studies in animal models and briefly review the mechanisms of phytoestrogen action and the critical concept of specific windows of developmental sensitivity to disruption. We then review in detail information regarding phytoestrogens and reproductive health outcomes, focusing mainly on studies of developmental phytoestrogen exposure in animal model systems, and finishing with available information from human studies.

Human phytoestrogen exposure

The amount of phytoestrogens consumed in the diet is highly variable and depends primarily on soy consumption; the resulting serum circulating levels of phytoestrogens are also highly variable (Verkasalo et al. 2001). For example, the highest circulating levels of genistein are seen in Asian populations who traditionally consume high levels of soy; Japanese men and women have approximately 500 nM genistein in circulation (Adlercreutz et al. 1994; Morton et al. 2002). There is also a large range of soy consumption across Europe. One study found mean serum genistein levels of 148 nM in a region with many vegetarians and much lower mean levels (2.6–22.6 nM) in other regions where fewer vegetarians lived (Peeters et al. 2007). This variability was also seen in another European study in which subjects were divided into four groups based on amount of reported dietary soy intake (lowest to highest) and the corresponding serum genistein levels were 14.3, 16.5, 119 and 378 nM (Verkasalo et al. 2001). Serum genistein levels in Finnish omnivores and vegetarians were 4.9 nM and 17.1 nM, respectively (Adlercreutz et al. 1994). Americans, in general, have low levels of genistein because soy is not prevalent in the diet. A non-representative subset of samples from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed an average serum genistein level of 17.4 nM with about half of the samples tested having non-detectable levels (Valentin-Blasini et al. 2003).

Because of maternal dietary phytoestrogen consumption, human fetuses are exposed to phytoestrogens during in utero development (Foster et al. 2002; Franke et al. 1998). The fetus is exposed to substances in maternal serum through the filter of the placenta. Although in theory the placenta serves as a barrier to protect the fetus from exposure to harmful chemicals, in fact most drugs and environmental chemicals enter the fetal circulation by either passive diffusion or active transport (Syme et al. 2004). An important modifier of fetal exposure is binding of chemicals to maternal serum proteins. For example, human steroid hormone binding protein (SHBG) binds estradiol with high affinity, and likely protects the fetus from effects of maternal estradiol on the brain and reproductive tract. However, human pregnancy plasma, which includes SHBG, has negligible affinity for phytoestrogens (Milligan et al. 1998), so fetal exposure to phytoestrogens is directly related to the maternal serum circulating level. The fetal counterpart to serum albumin is α-fetoprotein (AFP), the major serum constituent in the fetus. In rodents, AFP efficiently binds estradiol and could also serve to protect the fetus from its developmental effects. However, human AFP does not bind estradiol (Keel et al. 1992), and neither type of AFP binds phytoestrogens, so the presence of AFP in human fetal serum is not protective. Indeed, genistein and daidzein are detected in amniotic fluid from second trimester pregnancies at levels similar to those observed in adult serum, and 10–20-fold higher than average amniotic fluid estradiol levels at that time in pregnancy (Foster et al. 2002; Robinson et al. 1977).

Although human infants can be exposed to phytoestrogens via breast milk (Franke et al. 1998), the highest human exposure to phytoestrogens occurs in infants consuming soy-based infant formulas (Cao et al. 2009; Setchell et al. 1997). Infants fed exclusively soy-based formula have serum genistein levels of 1–10 µM when tested at random time intervals after feeding (Cao et al. 2009). Differences in the time of serum collection after feeding may explain the approximately 10-fold difference in values from different individuals. The estrogenic activity of soy-based formula in human infants was documented recently in a mostly cross-sectional study of plausible effects of estrogen exposure in male and female infants fed breast milk, soy formula, or cow milk formula (Bernbaum et al. 2008). Vaginal/introital wall cells in all the girls showed estrogen effects at birth, and largely lost them by about three months. The two girls fed soy formula and studied at six months showed re-estrogenization (Fig. 1). This small study is consistent with an estrogen effect from the soy formula, and suggests that further study of this simple and interpretable endpoint is worthwhile.

Figure 1. Maturation index of vaginal wall cells over time in infants fed breast milk, cow-based formula, or soy-based formula.

Maturation index is expressed as the percent of superficial cells plus half of the percent of intermediate cells on a Papanicolau smear of vaginal introitus cells from female infants. Curves extrapolated from data obtained from 11 or 12 infants per group. Dotted line segments connect observations from multiple visits by the same child at different ages. Figure adapted with permission from Environ Health Perspect (Bernbaum et al. 2008).

Relevance of animal models to human exposure levels

Ideally, studies to examine the effects of phytoestrogens on humans would be done in human subjects. However, there is wide variation in human exposures, these exposures are difficult to measure accurately, and the exposures are inherently difficult to control effectively (Verkasalo et al. 2001). There is also extensive variability in the phytoestrogen content of many dietary sources over time, whether standard food products or commercial botanical extracts sold as dietary supplements (Thompson et al. 2006). Furthermore, not all humans metabolize phytoestrogens the same way because of differences in activity of metabolizing enzymes and the influence of gut microflora on phytoestrogen bioavailability (de Cremoux et al. 2010). Together, these factors complicate both design and interpretation of human studies, and combined with the ethical issues regarding experimentation in humans, have led to extensive reliance on studies that utilize animal models.

The relevance to human health of studies performed in animal models has been questioned because in many of the animal studies exposure to phytoestrogens was by a non-oral route, whereas most human phytoestrogen exposure is from dietary intake (Verkasalo et al. 2001). Non-oral exposures are frequently chosen for rodent models of developmental phytoestrogen exposure because the size difference between rodents and humans, particularly in the neonatal period, precludes achieving similar serum phytoestrogen levels by an oral exposure route. Given that the serum concentration determines the amount of bioactive chemical to reach a target tissue, we believe that the serum measurement is the most important parameter to consider when attempting to model human exposures. This idea has been substantiated for genistein in two recent publications where direct comparisons of biological effects were made after exposure via different routes and forms of the chemical (Cimafranca et al. 2010; Jefferson et al. 2009a).

Pharmacokinetic analyses of subcutaneous exposure of neonatal mice to genistein and oral exposure to genistin or genistein demonstrated that oral exposure to genistin results in peak circulating levels of total genistein that are higher than following subcutaneous injection, but the total area under the curve over a 24 hour period is very similar (Fig. 2)(Jefferson et al. 2009a). Both exposure methods result in similar biological effects, suggesting that both peak and sustained genistein levels contribute to biological outcomes. In contrast, following an orally administered dose of genistein, there is ~90% less genistein found in circulation as compared to the same dose of genistein administered subcutaneously, and about a 20-fold lower peak genistein level (Jefferson et al. 2009a). Genistein also has much lower bioavailability than genistin when given orally to adult rats (Kwon et al. 2007). These data confirm that oral genistein dosing results in significantly lower tissue bioavailability when compared to both oral genistin exposure and subcutaneous genistein exposure. Furthermore, both oral genistin and subcutaneous genistein dosing in this neonatal mouse model system result in low micromolar serum circulating total genistein levels that closely approximate the levels measured in infants on soy-based infant formula (Fig. 2)(Cao et al. 2009; Jefferson et al. 2009a). These findings support their use in modeling developmental exposure of human infants to phytoestrogens.

Figure 2. Serum circulating levels of genistein following neonatal exposure by different routes.

Data plotted are mean serum genistein levels at the indicated times after dosing. Blue lines, oral genistin 37.5 mg/kg in corn oil, data from Jefferson et al. 2009a; Red lines, subcutaneous (SQ) genistein 50 mg/kg in corn oil, data from Doerge et al. 2002; Green lines, oral genistein 50 mg/kg in soy formula/corn oil mixture, data from Cimafranca et al. 2010. Total serum genistein shown in solid lines; aglycone fraction shown in dotted lines. Single orange points on right side of graph are the 25th, 50th, 75th percentiles and highest level of total serum genistein in human infants on soy formula at random time points after feeding, data from Cao et al. 2009.

Mechanisms of phytoestrogen action

The mechanisms of action of various phytoestrogens have been reviewed recently (Dang 2009; Li & Tollefsbol 2010; Lorand et al. 2010; Shanle & Xu 2011) and therefore will only be mentioned briefly here. As the name implies, phytoestrogens can interact with the classical estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, which mediate many of their downstream actions. Their affinities for ERα and ERβ are relatively weak compared to estradiol, and they can have agonist or antagonist activity depending on whether estradiol is also present (Shanle & Xu 2011). This is in contrast to the well-known endocrine disrupting chemical diethylstilbestrol (DES), which has higher affinity than estradiol for the estrogen receptors that mediate the majority of its actions (Korach & McLachlan 1985; Shanle & Xu 2011). Several phytoestrogens are selective estrogen receptor modulators that have greater affinity for ERβ than ERα (Lorand et al. 2010). However, phytoestrogens and xenoestrogens such as DES also affect numerous other signaling pathways including non-genomic signaling mediated by oxidative stress pathways, tyrosine kinases, nuclear factor-kappaB, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases (de Souza et al. 2010; Watson et al. 2007). In addition to classical estrogen receptors, phytoestrogens serve as ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, the non-classical estrogen receptor GPER1 (previously GPR30), the estrogen-related receptors, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Dang 2009; de Souza et al. 2010; Prossnitz & Barton 2009; Suetsugi et al. 2003). Besides direct actions to modulate signaling pathways, phytoestrogens can alter epigenetic marks by altering activities of DNA and histone methyltransferases, NAD-dependent histone deacetylases, and other modifiers of chromatin structure (Labinskyy et al. 2006; Li & Tollefsbol 2010; Shanle & Xu 2011). Last, phytoestrogens can competitively inhibit production of estradiol by aromatase (Kao et al. 1998; Shanle & Xu 2011), which would lead to lower endogenous estrogen levels. The complexity of phytoestrogen actions is increased by the fact that these compounds are frequently present in vivo as mixtures of several dietary components that can affect multiple signaling pathways or affect the same pathways in opposing directions.

Windows of developmental sensitivity

The fetus and neonate are highly sensitive to environmental chemical exposures because organogenesis, rapid growth, and extensive tissue differentiation occur during these developmental periods and therefore small perturbations can have important consequences. In addition, metabolic processing and elimination mechanisms are immature in the fetus and neonate, so detoxification is inefficient (Beath 2003; Chen et al. 2006). Furthermore, many developmental processes are dependent on steroid hormones and secreted proteins whose activities have the potential to be altered by phytoestrogens based on the mechanisms of action outlined above. For example, testosterone secreted by the fetal testis is a key mediator of male gonad and reproductive tract development (Park & Jameson 2005). Fetal exposure to estrogenic compounds can suppress testosterone synthesis, leading to cryptorchidism and adult testis dysfunction (Clark & Cochrum 2007; Wohlfahrt-Veje et al. 2009). In addition, exposure to estrogenic chemicals during fetal life disrupts female reproductive tract development by altering expression of genes encoding secreted signaling proteins critical for directing this process (Ma 2009); these effects have permanent consequences for reproductive tract morphology and function in both rodents and humans (Baird & Newbold 2005; Newbold et al. 2004).

Although most organ systems in the fetus are highly sensitive to developmental insults, this sensitivity persists during postnatal life in several specific organ systems because they continue to develop after birth. For example, in humans the brain continues to undergo significant growth and differentiation during the first several years of life, and there is evidence of continued brain development through late adolescence [reviewed in (Sisk & Zehr 2005)]. Similarly, in animals including humans, the female reproductive tract is not completely differentiated at birth, but continues to undergo cellular differentiation until just prior to the onset of puberty (Gray et al. 2001; Valdes-Dapena 1973). Many of these postnatal differentiation events are dependent at least in part on steroid hormone signaling. For this reason, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including phytoestrogens, could have a significant impact on postnatal development in ways that affect later reproductive health.

Phytoestrogen exposure and reproductive health in animal models

Reproductive health critically depends on proper sexually dimorphic fetal and postnatal development followed by sex-specific and coordinated functioning of the brain, gonads, reproductive tract, and external genitalia. Although other organ systems, particularly endocrine-related organs, also contribute to reproductive health, there is little information available regarding the impact of phytoestrogens on these other organs as they relate to reproductive function. For this reason we will limit the discussion below to the major organs and essential processes considered part of the reproductive system.

Estrous cycle

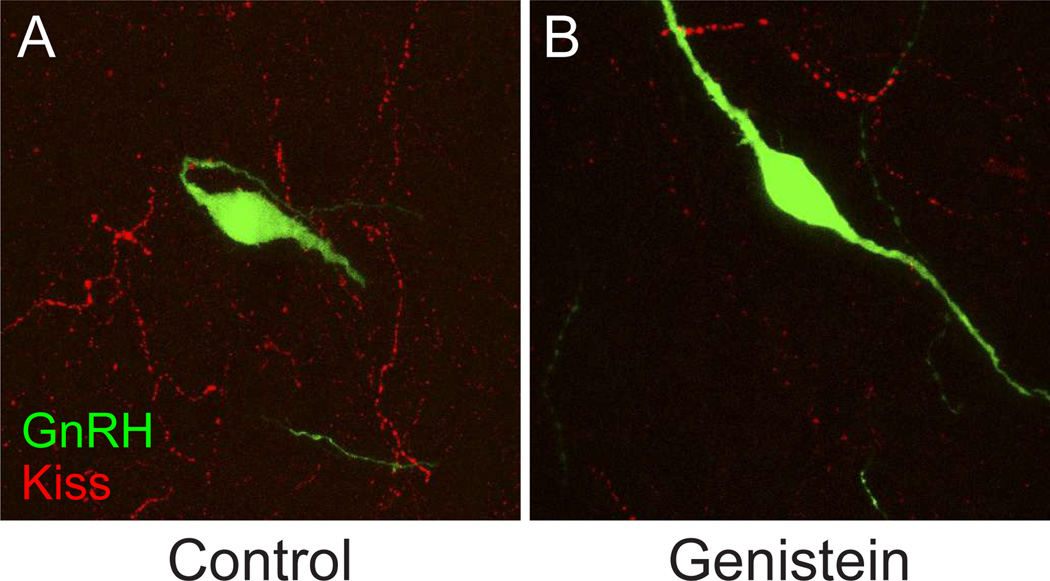

We have used a mouse model of neonatal exposure to the phytoestrogen genistein to study the impact of physiologically relevant levels of phytoestrogens on female reproductive health (Jefferson et al. 2009b; Jefferson et al. 2005). The initial dosing strategy achieved serum levels ranging from those observed in humans eating a non-vegetarian diet all the way to levels measured in infants fed soy-based infant formula as their major food source. Neonatal genistein treatment causes abnormal estrous cycles and anovulation as a result of abnormalities in hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis function (Jefferson et al. 2005). In the rat, neonatal genistein exposure alters pituitary sensitivity to a gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) challenge, with a low genistein dose causing increased sensitivity and higher doses causing decreased sensitivity as indicated by luteinizing hormone release (Faber & Hughes 1993). More recent work demonstrates that neonatal genistein alters hypothalamic kisspeptin signaling pathways and GnRH activity (Fig. 3) (Losa et al. 2011). These pathways regulate both timing of pubertal onset and estrous cyclicity, and so provide a likely explanation for the abnormal estrous cyclicity and anovulation observed in the mouse model. Based on studies in adult rats, resveratrol can also disrupt estrous cyclicity, though the underlying mechanism is not clear (Henry & Witt 2002).

Figure 3. Representative confocal images depicting the plexus of kisspeptin (Kiss) neuronal fibers surrounding GnRH neurons in the anterior hypothalamus.

The density of Kiss projections is reduced by approximately half in postnatal day 28 female rats following neonatal exposure for 4 days to 10 mg/kg body weight genistein as described previously (Losa et al. 2011). A, Control; B, Genistein-treated.

Sexually dimorphic behavior

Prenatally and postnatally, the brain develops in a sexually dimorphic fashion that contributes to differential reproductive behaviors in response to hormonal stimuli during adulthood (Henley et al. 2011; Roselli & Stormshak 2010; Sakuma 2009; Simerly 2002). For example, the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN) is substantially larger in males than in females; in rams and rats the size of this region is associated with sexual partner preference (Henley et al. 2011; Roselli & Stormshak 2010). The SDN size difference is a result of exposure to testosterone, generated by the testis, and estradiol, which is generated in the brain by aromatization of testosterone. Indeed, testosterone and estradiol serve as the most important factors to establish permanent sex differences in brain organization during the fetal and neonatal periods [reviewed in (Arnold 2009)]. Although most sex differences are likely established during prenatal and neonatal development, it was shown recently in the rat that new cells are added to sexually dimorphic nuclei during adolescence in response to steroid hormone treatments (Ahmed et al. 2008), demonstrating the long-term sensitivity of sexually dimorphic brain regions to steroid hormone-mediated signaling.

Several phytoestrogens affect brain development and sexual behavior in animal models. For example, exposure of male rat pups to resveratrol via nursing is associated with smaller SDN size and reduced sociosexual behavior in adulthood (Henry & Witt 2006). Coumestrol administration to neonatal female rats markedly reduces lordosis behavior in adulthood (Kouki et al. 2005). Finally, neonatal genistein exposure affects sexual behavior of adult male rats, an effect likely mediated by estrogen receptor beta (Sullivan et al. 2011; Wisniewski et al. 2003). Notably, all of these exposures occur during the neonatal period but affect adult behaviors, highlighting the importance of the timing of exposures in determining specific long-term outcomes.

Testis function

There is some evidence in animal models that developmental exposure to phytoestrogens affects testis function, but many studies find no effects so it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions (Cederroth et al. 2010). Several studies that do show alterations in testis function used long-term exposure protocols, beginning during gestation and continuing through adulthood. For example, two studies demonstrate that male rats chronically exposed to genistein have abnormalities in spermatogenesis (Delclos et al. 2001; Eustache et al. 2009). One of these studies also demonstrated that genistein caused alterations in sperm motility and a reduction in litter size accompanied by evidence of post-implantation embryo loss when the adult rats underwent fertility testing (Eustache et al. 2009). In a set of very nicely designed twin studies in marmosets, neonatal soy milk exposure was shown to alter testis cellular morphology and reduce serum testosterone levels when compared to the same parameters in twin siblings fed standard milk formula, but fertility was not different between the two groups (Sharpe et al. 2002; Tan et al. 2006).

Ovarian function

Female germ cells complete proliferation and begin meiosis prenatally, then arrest in meiosis I prior to or at the time of birth. Prenatal development is absolutely critical for female reproductive health because this is the last time that new daughter germ cells are generated. In rodents, primordial follicles form during the first postnatal week by migration of pre-granulosa cells to surround individual oocytes as oocyte nests break down. Exposure to genistein during this process causes failure of oocyte nest breakdown and leads to the development of multi-oocyte follicles (Chen et al. 2007; Cimafranca et al. 2010; Losa et al. 2011). It does not appear that the occurrence of multioocyte follicles impacts fertility; however, because embryos derived from neonatal genistein-treated mice are fully competent to develop to term if transferred into pseudopregnant control mice (Jefferson et al. 2009b).

Female reproductive tract function

In newborn rodents, the female reproductive tract is a simple bifurcated tube comprised of an outer epithelium, a muscle layer, a thin stromal layer, and a simple columnar epithelium. Extensive gross morphological and cellular differentiation begins in the immediate postnatal period and is complete by about postnatal day 15 in the mouse (Gray et al. 2001). This differentiation process is under regulatory control of homeobox transcription factors, particularly the posterior Hoxa genes, and secreted signaling molecules that induce formation of the morphologically distinct reproductive tract regions: oviduct, uterus, cervix, and vagina (Ma 2009; Umezu et al. 2010). In addition to regional differentiation, the endometrial epithelium undergoes glandular morphogenesis postnatally to form branched glandular structures in the endometrial stroma. These cellular and regional differentiation processes are exquisitely sensitive to disruption by steroid hormone signaling (Gray et al. 2001).

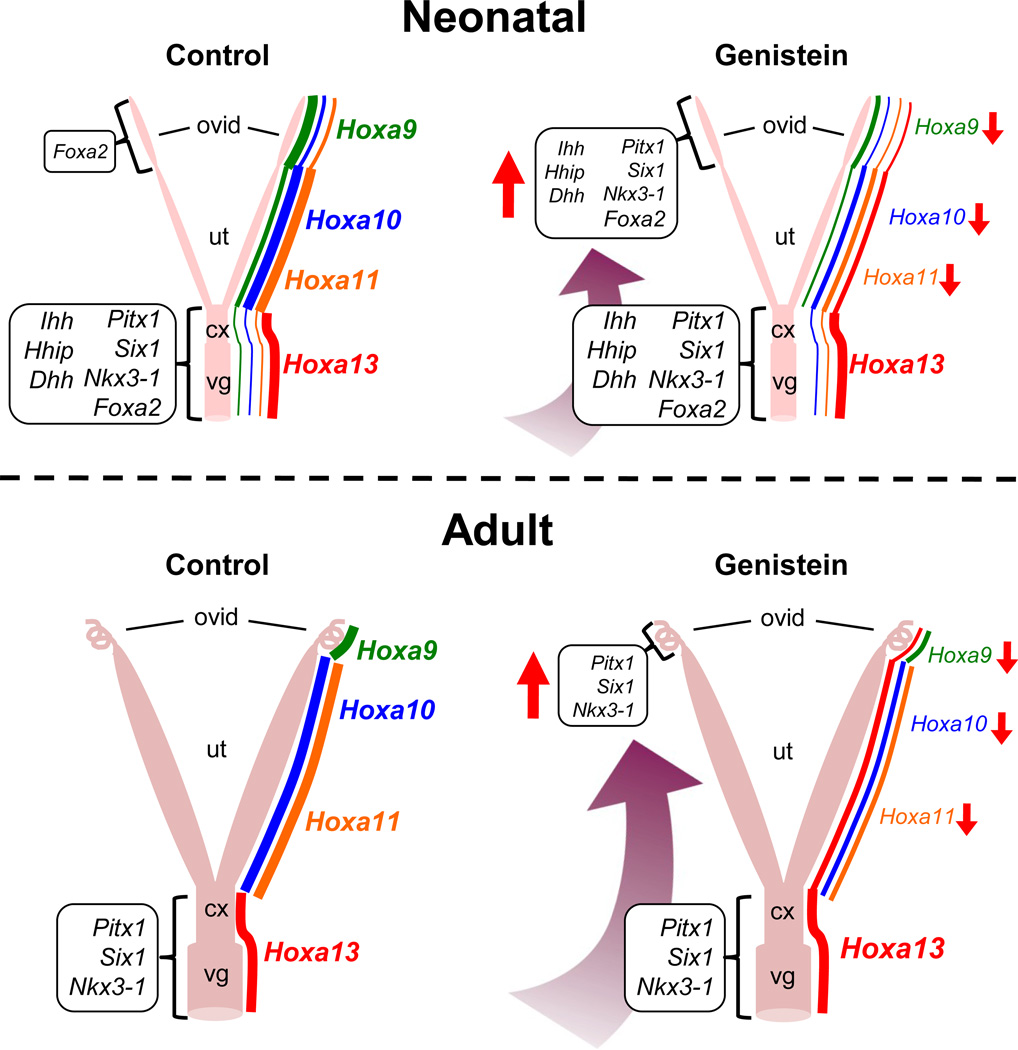

Phytoestrogens dramatically alter development of the rodent female reproductive tract. Neonatal genistein exposure disrupts oviductal morphogenesis by altering hedgehog signaling pathways and expression of homeobox genes and other transcription factors (Jefferson et al. 2011). As a result, the oviduct becomes “posteriorized”, i.e., expresses genes and proteins normally observed only in posterior regions of the reproductive tract (cervix and vagina) (Fig. 4). The abnormally expressed genes include several developmentally important homeobox transcription factors that are absent in control oviducts, including Pitx1 and Six1 (Jefferson et al. 2011). In addition, microarray analysis of oviduct gene expression on pregnancy day 2 revealed that neonatal genistein exposure causes significant alterations in gene expression in the category of inflammatory response pathways, many of which are hormonally regulated, suggesting the presence of alterations in oviductal mucosal immune responses during early pregnancy that could impact embryo survival and development (Jefferson et al. 2011).

Figure 4. Schematic representation of posteriorization of the female reproductive tract after neonatal genistein exposure.

Upper panels: Neonatal genistein exposure alters expression of Hoxa genes along anterior-posterior axis of the postnatal day 5 uterus. In addition, hedgehog family secreted signaling factors and other transcription factors normally expressed in the cervix and vagina are abnormally expressed in the oviduct after 5 days of genistein treatment. Lower panels: Alterations in expression of Hoxa genes and other transcription factors persist in the adult female reproductive tract following neonatal genistein exposure. Hoxa gene expression depicted on right side of each schematic; line thickness and font size indicate relative expression levels. Expression of other genes indicated in boxes to left of each schematic; font size and direction of red arrows indicate relative expression levels compared to controls. Ovid, oviduct; Ut, uterus; Cx, cervix; Vg, vagina. Information presented is from Jefferson et al. 2011.

There is a wealth of information available regarding effects of developmental exposure to phytoestrogens on uterine morphology and function. For example, treatment of immature rats for one week with resveratrol increases uterine wet weight and glandular morphogenesis (Singh et al. 2011). These changes are accompanied by alterations in several endometrial pro-survival or anti-apoptotic factors, but whether or not resveratrol treatment at this time in development has permanent effects is unknown. Treatment of neonatal rats with coumestrol causes early vaginal opening and an initial increase in uterine wet weight during the time of treatment followed by a later decrease in adult uterine weight (Losa et al. 2011; Medlock et al. 1994). This is also true for mice treated neonatally with DES (Newbold et al. 2004). When coumestrol is administered to rats slightly later, during postnatal days 10–14 that are critical for glandular morphogenesis, fewer endometrial glands are observed in the adults and estrogen receptor expression is reduced (Medlock et al. 1995a; Medlock et al. 1994). Mice treated neonatally with coumestrol develop squamous metaplasia and have abnormal collagen deposition in the uterine wall by 22 months of age (Burroughs et al. 1990a). Together, these studies overwhelmingly support the concept that brief exposure to phytoestrogens during developmentally sensitive periods can have permanent effects on uterine morphology and function.

Although we are mainly focusing here on reproductive outcomes, developmental phytoestrogen exposure is also associated with uterine carcinogenesis. Indeed, mice treated neonatally with genistein have a 35% incidence of uterine cancer by 18 months of age (Newbold et al. 2001). This incidence is similar to the incidence seen when mice are given an equally estrogenic dose of DES, suggesting that it is mediated by estrogen receptor signaling. Of note, the cancer phenotype is not observed if the DES-exposed mice are ovariectomized prior to puberty, indicating that a “second hit” of steroid hormone exposure is required (Newbold et al. 1990). In contrast, a recent study demonstrated beneficial effects of neonatal exposure to phytoestrogens on uterine carcinogenesis (Begum et al. 2006). This study used mice heterozygous for a knockout allele of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) that have a very high incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma by 12 months of age. Neonatal exposure to genistein at the same doses used by Newbold et al. (Newbold et al. 2001) strongly suppressed endometrial carcinogenesis in the Pten+/− model. Of note, the genistein exposed Pten+/− mice demonstrated alterations in endometrial stromal morphology and reductions in expression of Hoxa10 and Hoxa11 similar to those we have observed after treating wild type mice with genistein (WNJ and CJW, unpublished observations), suggesting that the different outcome was related to differences in cancer etiology in the two models and not differences in genistein effects.

The mechanisms underlying persistence of altered uterine phenotypes into adulthood after these developmental exposures, and in the case of neonatal DES-exposed mice, transmission to subsequent generations (Newbold et al. 1998, 2000), are not known and are active areas of current research. The most likely explanation is that endocrine disruption during development results in permanent epigenetic changes responsible for the abnormal phenotype that are maintained into adulthood and can be stably transmitted to the next generation. There are precedents for epigenetic changes occurring after developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors including phytoestrogens and other environmental cues (Jirtle & Skinner 2007; Jones & Baylin 2007; Wade & Archer 2006). These exposures can alter DNA methylation status of specific genes (Li et al. 2007; Tang et al. 2008) or alter methylation patterns on a more global scale (Anway et al. 2005; Dolinoy et al. 2007) suggesting that methylation is one potential mechanism for this phenomenon. Indeed, there is some evidence in mice that prenatal DES exposure can increase methylation of Hoxa10, a gene important for uterine development and adult uterine function (Bromer et al. 2009). However, the functional significance of these methylation changes is not known, and similar alterations in Hoxa10 methylation were not observed after prenatal genistein or daidzein exposure (Akbas et al. 2007). A recent study demonstrated that exposure of ovariectomized adult rats to high doses of genistein caused subtle decreases in methylation of the steroidogenic factor 1 promoter associated with increased expression of this gene in the endometrium, but whether the protein level was altered and whether the effects were permanent is unknown (Matsukura et al. 2011). We anticipate that future studies that examine a more complete scope of epigenetic alterations such as histone modifications and alterations in three-dimensional chromatin structure will help to shed light on the mechanistic basis of the permanent reproductive tract alterations observed after developmental phytoestrogen exposure.

Reproductive tract influence on embryo development in the mouse

It should come as no surprise that abnormalities in reproductive tract development can result in alterations in embryo development. Adult females treated neonatally with genistein occasionally ovulate spontaneously up to about 8 weeks of age, but after that time remain in a state of persistent estrous and are anovulatory (Jefferson et al. 2005). They can, however, be superovulated with gonadotropins and then bred to fertile males. These mice achieve pregnancy, but fertilization is delayed by several hours compared to controls (Jefferson et al. 2009b). If the pronuclear stage embryos are removed from the oviduct and cultured in vitro, they develop normally to the blastocyst stage and can develop to term if transferred into control pseudopregnant females. If left in the oviduct; however, by the 3rd day of pregnancy about half of the embryos are reabsorbed (Fig. 5). The surviving embryos develop in vivo at a faster rate than controls and have an altered trophectoderm to inner cell mass ratio (WNJ and CJW, unpublished observations). Some of the embryos that survive transit through the oviduct implant in the uterus, but the implantation sites are abnormal and the embryos do not develop to term (Jefferson et al. 2005). This is not a consequence of an abnormal steroid hormone milieu because serum levels of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone in these mice are within the normal range on days 6, 8, and 10 of pregnancy (Jefferson et al. 2005). Instead, the uterus is not competent to support embryo development, even if blastocysts from untreated control mice are transferred into pseudopregnant genistein-treated mice (Jefferson et al. 2009b). These findings demonstrate that neonatal phytoestrogen exposure alters female reproductive tract development in ways that can directly affect the development of the subsequent generation of embryos.

Figure 5. Embryo loss during transit through the oviduct in adult mice treated neonatally with genistein.

Embryos were flushed from the oviduct and uterus of control (white bars) and neonatal genistein-treated (black bars) superovulated mice at the indicated times after human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) administration and mating. Graph shows mean number ± SEM of embryos per mouse. Asterisks, p<0.05 compared to control at same time point. Schematic above graph indicates expected embryo stage and location within the female reproductive tract at the different time points. Modified from Jefferson et al. 2009b.

External genitalia

Male differentiation of the external genitalia occurs prenatally in response to testosterone produced by the fetal testis and dihydrotestosterone generated locally in external genital tissues (Park & Jameson 2005). Several studies have demonstrated effects of phytoestrogens on external genital development or function in rodents. Gestational and/or lactational genistein exposure can cause a reduction in anogenital distance in male mice and rats (Ball et al. 2010; Levy et al. 1995; Wisniewski et al. 2005; Wisniewski et al. 2003). One study demonstrated that erectile function is abnormal in juvenile rats exposed to daidzein for three months (Pan et al. 2008). Last, hypospadias is observed in 25% of male mice exposed prenatally to genistein (Vilela et al. 2007). This finding is likely explained by genistein-mediated alterations in expression of genes important for urethral morphogenesis including some regulated by estrogen receptor signaling (Ross et al. 2011).

In the absence of prenatal androgen exposure, female external genitalia will form. Completion of female mouse external genitalia development is delayed in comparison to males because at birth there is incomplete fusion of the urethral folds. Urethral fold fusion is not complete until after postnatal day 5 and is sensitive to disruption by estrogenic chemicals in the neonatal period (Miyagawa et al. 2002). We recently demonstrated that female mice exposed neonatally to genistein have a 100% incidence of hypospadias (Padilla-Banks et al. 2011). As in males, exposure of female rats during gestation to phytoestrogens including genistein and lignans can cause reduced anogenital distance (Delclos et al. 2009; Tou et al. 1998).

Phytoestrogen exposure and reproductive health in humans

Although work in animal model systems suggests that phytoestrogens impact reproductive health, we next consider evidence in humans that this might be the case. Human studies on this topic are difficult to carry out given their typical complexity and dependence on relatively long term observational studies rather than the treatment-based outcomes measured in animal models. Nevertheless, several studies have been published regarding effects of developmental phytoestrogen exposure on the brain, reproductive tract, and external genitalia that are relevant to human reproduction.

Sexually dimorphic behavior

Studies in animal models have indicated that many of the effects of androgens on behavior are mediated by activation of estrogen receptor-based signaling, presumably by aromatization of androgens to generate estrogen within the brain (Wu & Shah 2011). It is well established in humans that prenatal exposure to androgens can result in masculinization of behavior (Hines 2008). There is much less information available regarding effects of estrogens or phytoestrogens on sexually dimorphic behavior in humans. However, a longitudinal study examining the impact of human infant exposure to soy-based formula on gender role-play behavior was published recently (Adgent et al. 2011b). This study of over 7000 children enrolled in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) found an association between early life soy exposure (starting prior to age 4 months) and masculinized play behavior in girls at age 42 months. There were no measurable effects in boys, and the effects on girls were attenuated by 57 months of age. The consistency of these findings with behavioral changes observed in well-controlled studies using animal models suggest that evidence obtained from animal studies regarding effects of exposure to estrogenic chemicals in early life on adult reproductive behavior is relevant to behavioral outcomes in humans.

Puberty

The timing of pubertal onset is a result of complex interactions between endocrine system organs including the brain, gonads, and adipose tissue that depend on peptide and steroid hormone actions, and as such could be affected by early life phytoestrogen exposure. A subset of girls in the ALSPAC cohort described above who provided information regarding pubertal timing (N=2,920) was used to examine associations between early life soy exposure and timing of menarche (Adgent et al. 2011a). The early soy exposure group had a 25% increased risk of menarche before age 12 when compared to girls fed other types of infant formula or milk. However, the study was limited by the fact that only 2% of the subjects had early soy exposure, and loss to follow up was significant.

A recent case-control study of ~200 Korean girls ages 8–10 demonstrated that high serum isoflavone levels (daidzein and genistein) are associated with central precocious puberty (Kim et al. 2011). Central precocious puberty was diagnosed using strict criteria of breast budding prior to age 8, bone age advanced more than one year, and a positive GnRH stimulation test. In fact, there was about a four-fold increased risk of central precocious puberty in girls who had total isoflavone levels in the middle (30–70 nM) or high (≥70 nM) range as compared to the lowest range (<30 nM). This study is in contrast to two observational studies of the timing of pubertal onset that demonstrated an association of higher urinary isoflavone levels with slightly later onset of breast development (Cheng et al. 2010; Wolff et al. 2008). One of these studies was in an ethnically mixed population of 9-year old girls in New York City and the other used a prospectively followed cohort of children in Germany. A multicenter prospective longitudinal study of over 1100 girls in the U.S. found essentially no association between urinary phytoestrogen levels and onset of breast development (Wolff et al. 2008). Although there were many methodological differences between the studies, one interpretation of the slightly conflicting results is that phytoestrogen exposure early in the pre-pubertal period when endogenous estradiol levels are low could predispose girls to central precocious puberty, whereas later phytoestrogen exposure could serve to interfere with endogenous estrogen-mediated stimulation of breast development because of weak estrogen receptor agonist activity.

Female reproductive tract

The consequences of exposing pregnant women to DES made clear the potential impact of estrogenic chemicals on female reproductive tract development in humans. In addition to the increased incidence of vaginal cancer in daughters of DES-treated women, there is also a high incidence of female reproductive tract malformations that are associated with ectopic pregnancy and premature delivery, and an increased incidence of uterine fibroids (Baird & Newbold 2005; Stillman 1982). The DES experience also demonstrated the critical importance of timing and dose of exposure to estrogenic chemicals in determining extent of abnormalities in human female reproductive tract development, with a higher incidence and higher severity of abnormalities after earlier exposure to higher doses (Jefferies et al. 1984).

To date, only two studies have examined the relationship between phytoestrogen exposure and adult female reproductive tract function; in these studies the exposure was postnatal. One small retrospective study found that women fed soy formula as infants reported longer menstrual bleeding and more dysmenorrhea than women who were not exposed to soy formula (Strom et al. 2001). The second study, which included almost 20,000 women, linked use of soy formula during infancy with a slightly increased risk of early diagnosis of uterine fibroids (D'Aloisio et al. 2010). Although fibroids have not been reported following neonatal phytoestrogen exposure in animal models, these findings are consistent with the observations that rats and humans exposed to DES during developmental periods have an increased incidence of uterine fibroids as adults (Baird & Newbold 2005; Cook et al. 2007).

Male reproductive tract

Male fetuses also have adverse effects of developmental exposure to estrogenic chemicals that affect their ability to reproduce. A collaborative cohort study of about 1200 sons of DES-treated women demonstrated an increased incidence of cryptorchidism, epididymal cysts, and inflammation or infection of the testis, particularly when exposure occurred before gestation week 11 (Palmer et al. 2009). These findings are consistent with reported effects of estradiol in inhibiting insulin-like 3-mediated signaling that is required for testicular descent and estradiol-mediated inhibition of anti-Müllerian hormone activity that is important for Müllerian duct regression (Cederroth et al. 2007; Visser et al. 1998). There are conflicting results in the literature regarding whether or not DES-exposed males have an increased risk of hypospadias, with several studies indicating an increased risk but other studies not replicating this finding (Brouwers et al. 2010). There is a single report of an approximately five-fold increased risk of hypospadias in sons of mothers who ate a vegetarian diet during pregnancy (North & Golding 2000). Whether this finding is due to phytoestrogen exposure or whether it is caused by concomitant ingestion of other chemicals, e.g., pesticides, that could be more prevalent in a vegetarian diet is unknown. However, a mouse study regarding the effects of genistein alone or combined with the pesticide vinclozolin suggests that both chemicals can increase the incidence of hypospadias (Vilela et al. 2007).

Summary

There is overwhelming evidence in animal models that phytoestrogen exposure can have significant consequences for reproductive health. The effects observed depend on the dose and route of exposure because these parameters impact the final serum level of the bioactive compound. In addition, the timing of exposure is critical in determining phenotypic effects because different tissues have species-specific windows of sensitivity to morphological and functional disruption. These sensitive windows generally begin in the early prenatal period and extend in some cases through adulthood. As more phytoestrogens are recognized or developed as therapeutic compounds, it will be important to examine carefully the effects of these chemicals on reproductive outcomes using animal models that replicate human exposure levels.

Although the effects of phytoestrogens have been evaluated in only a small number of human studies, several of these studies are consistent with findings in animal models after taking into consideration the different developmental timing of specific tissues. Other human studies are more difficult to interpret because of inherent weaknesses in study designs involving large populations of human subjects, difficulties in quantifying phytoestrogen exposures, and an inability to fully control unknown factors in the diet or from the environment that could influence outcomes. There is a need for additional well-designed prospective human studies that limit these variables as much as possible and focus on environmentally relevant levels of phytoestrogen exposure. Despite their limitations, information gathered from the published human studies combined with the large number of animal studies already available clearly demonstrates that phytoestrogens have the ability to permanently reprogram adult tissue responses after a developmental exposure, and that these altered tissue responses are important for reproductive health. These findings should be taken into account when recommendations are made regarding dietary or therapeutic phytoestrogen intake, while keeping in mind developmentally sensitive time points.

Acknowledgements

We thank Walter Rogan and Humphrey Yao (NIEHS) for critical review of the manuscript, and Lois Wyrick (NIEHS) for assistance with artwork.

Support: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01-ES102405, CJW) and by the NIH, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (R01-ES016001, HBP).

References

- Adgent M, Daniels J, Rogan W, Adair L, Edwards L, Westreich D, Maisonet M, Marcus M. Early life soy exposure and age at menarche. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011a doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01244.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adgent M, Daniels JL, Edwards L, Siega-Riz AM, Rogan WJ. Early life soy exposure and gender-role play behavior in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2011b doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103579. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz H, Fotsis T, Watanabe S, Lampe J, Wahala K, Makela T, Hase T. Determination of lignans and isoflavonoids in plasma by isotope dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Cancer Detect Prev. 1994;18:259–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed EI, Zehr JL, Schulz KM, Lorenz BH, DonCarlos LL, Sisk CL. Pubertal hormones modulate the addition of new cells to sexually dimorphic brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:995–997. doi: 10.1038/nn.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbas GE, Fei X, Taylor HS. Regulation of HOXA10 expression by phytoestrogens. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E435–442. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00167.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam A, Abu-Rustum N, Carter J, Krychman M. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome associated with increased soy intake. J Sex Med. 2005;2:338–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anway MD, Cupp AS, Uzumcu M, Skinner MK. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors and male fertility. Science. 2005;308:1466–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.1108190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP. The organizational-activational hypothesis as the foundation for a unified theory of sexual differentiation of all mammalian tissues. Horm Behav. 2009;55:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird DD, Newbold R. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is associated with uterine leiomyoma development. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;20:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball ER, Caniglia MK, Wilcox JL, Overton KA, Burr MJ, Wolfe BD, Sanders BJ, Wisniewski AB, Wrenn CC. Effects of genistein in the maternal diet on reproductive development and spatial learning in male rats. Horm Behav. 2010;57:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman HL, Patisaul HB. Disrupted female reproductive physiology following neonatal exposure to phytoestrogens or estrogen specific ligands is associated with decreased GnRH activation and kisspeptin fiber density in the hypothalamus. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:988–997. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beath SV. Hepatic function and physiology in the newborn. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:337–346. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum M, Tashiro H, Katabuchi H, Suzuki A, Kurman RJ, Okamura H. Neonatal estrogenic exposure suppresses PTEN-related endometrial carcinogenesis in recombinant mice. Lab Invest. 2006;86:286–296. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetts HW, Underwood EJ, Shier FL. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in Western Australia. Aust Vet J. 1946;22:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1946.tb15473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernbaum JC, Umbach DM, Ragan NB, Ballard JL, Archer JI, Schmidt-Davis H, Rogan WJ. Pilot studies of estrogen-related physical findings in infants. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:416–420. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromer JG, Wu J, Zhou Y, Taylor HS. Hypermethylation of homeobox A10 by in utero diethylstilbestrol exposure: an epigenetic mechanism for altered developmental programming. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3376–3382. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers MM, van der Zanden LF, de Gier RP, Barten EJ, Zielhuis GA, Feitz WF, Roeleveld N. Hypospadias: risk factor patterns and different phenotypes. BJU Int. 2010;105:254–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs CD, Mills KT, Bern HA. Long-term genital tract changes in female mice treated neonatally with coumestrol. Reprod Toxicol. 1990a;4:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(90)90007-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs CD, Mills KT, Bern HA. Reproductive abnormalities in female mice exposed neonatally to various doses of coumestrol. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1990b;30:105–122. doi: 10.1080/15287399009531415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Calafat AM, Doerge DR, Umbach DM, Bernbaum JC, Twaddle NC, Ye X, Rogan WJ. Isoflavones in urine, saliva, and blood of infants: data from a pilot study on the estrogenic activity of soy formula. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:223–234. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederroth CR, Auger J, Zimmermann C, Eustache F, Nef S. Soy, phyto-oestrogens and male reproductive function: a review. Int J Androl. 2010;33:304–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederroth CR, Schaad O, Descombes P, Chambon P, Vassalli JD, Nef S. Estrogen receptor alpha is a major contributor to estrogen-mediated fetal testis dysgenesis and cryptorchidism. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5507–5519. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrareddy A, Muneyyirci-Delale O, McFarlane SI, Murad OM. Adverse effects of phytoestrogens on reproductive health: a report of three cases. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Aleksa K, Woodland C, Rieder M, Koren G. Ontogeny of drug elimination by the human kidney. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:160–168. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Jefferson WN, Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Pepling ME. Estradiol, progesterone, and genistein inhibit oocyte nest breakdown and primordial follicle assembly in the neonatal mouse ovary in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3580–3590. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Remer T, Prinz-Langenohl R, Blaszkewicz M, Degen GH, Buyken AE. Relation of isoflavones and fiber intake in childhood to the timing of puberty. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:556–564. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimafranca MA, Davila J, Ekman GC, Andrews RN, Neese SL, Peretz J, Woodling KA, Helferich WG, Sarkar J, Flaws JA, et al. Acute and chronic effects of oral genistein administration in neonatal mice. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:114–121. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BJ, Cochrum RK. The steroidogenic acute regulatory protein as a target of endocrine disruption in male reproduction. Drug Metab Rev. 2007;39:353–370. doi: 10.1080/03602530701519151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Davis BJ, Goewey JA, Berry TD, Walker CL. Identification of a sensitive period for developmental programming that increases risk for uterine leiomyoma in Eker rats. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:121–136. doi: 10.1177/1933719106298401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aloisio AA, Baird DD, DeRoo LA, Sandler DP. Association of intrauterine and early-life exposures with diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata by 35 years of age in the Sister Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:375–381. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang ZC. Dose-dependent effects of soy phyto-oestrogen genistein on adipocytes: mechanisms of action. Obes Rev. 2009;10:342–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cremoux P, This P, Leclercq G, Jacquot Y. Controversies concerning the use of phytoestrogens in menopause management: bioavailability and metabolism. Maturitas. 2010;65:334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza PL, Russell PJ, Kearsley JH, Howes LG. Clinical pharmacology of isoflavones and its relevance for potential prevention of prostate cancer. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:542–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delclos KB, Bucci TJ, Lomax LG, Latendresse JR, Warbritton A, Weis CC, Newbold RR. Effects of dietary genistein exposure during development on male and female CD (Sprague-Dawley) rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:647–663. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delclos KB, Weis CC, Bucci TJ, Olson G, Mellick P, Sadovova N, Latendresse JR, Thorn B, Newbold RR. Overlapping but distinct effects of genistein and ethinyl estradiol (EE(2)) in female Sprague-Dawley rats in multigenerational reproductive and chronic toxicity studies. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;27:117–132. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diel P, Schulz T, Smolnikar K, Strunck E, Vollmer G, Michna H. Ability of xeno- and phytoestrogens to modulate expression of estrogen-sensitive genes in rat uterus: estrogenicity profiles and uterotropic activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;73:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy DC, Huang D, Jirtle RL. Maternal nutrient supplementation counteracts bisphenol A-induced DNA hypomethylation in early development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13056–13061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703739104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustache F, Mondon F, Canivenc-Lavier MC, Lesaffre C, Fulla Y, Berges R, Cravedi JP, Vaiman D, Auger J. Chronic dietary exposure to a low-dose mixture of genistein and vinclozolin modifies the reproductive axis, testis transcriptome, and fertility. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1272–1279. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber KA, Hughes CL., Jr Dose-response characteristics of neonatal exposure to genistein on pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin releasing hormone and volume of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN-POA) in postpubertal castrated female rats. Reprod Toxicol. 1993;7:35–39. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(93)90007-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster WG, Chan S, Platt L, Hughes CL., Jr Detection of phytoestrogens in samples of second trimester human amniotic fluid. Toxicol Lett. 2002;129:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke AA, Custer LJ, Wang W, Shi CY. HPLC analysis of isoflavonoids and other phenolic agents from foods and from human fluids. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:263–273. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CA, Bartol FF, Tarleton BJ, Wiley AA, Johnson GA, Bazer FW, Spencer TE. Developmental biology of uterine glands. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1311–1323. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.5.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley CL, Nunez AA, Clemens LG. Hormones of choice: the neuroendocrinology of partner preference in animals. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LA, Witt DM. Resveratrol: phytoestrogen effects on reproductive physiology and behavior in female rats. Horm Behav. 2002;41:220–228. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LA, Witt DM. Effects of neonatal resveratrol exposure on adult male and female reproductive physiology and behavior. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:186–195. doi: 10.1159/000091916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines M. Early androgen influences on human neural and behavioural development. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84:805–807. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies JA, Robboy SJ, O'Brien PC, Bergstralh EJ, Labarthe DR, Barnes AB, Noller KL, Hatab PA, Kaufman RH, Townsend DE. Structural anomalies of the cervix and vagina in women enrolled in the Diethylstilbestrol Adenosis (DESAD) Project. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;148:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(84)80033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson WN, Doerge D, Padilla-Banks E, Woodling KA, Kissling GE, Newbold R. Oral exposure to genistin, the glycosylated form of genistein, during neonatal life adversely affects the female reproductive system. Environ Health Perspect. 2009a;117:1883–1889. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Clark G, Newbold RR. Assessing estrogenic activity of phytochemicals using transcriptional activation and immature mouse uterotrophic responses. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Goulding EH, Lao SP, Newbold RR, Williams CJ. Neonatal exposure to genistein disrupts ability of female mouse reproductive tract to support preimplantation embryo development and implantation. Biol Reprod. 2009b;80:425–431. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Newbold RR. Adverse effects on female development and reproduction in CD-1 mice following neonatal exposure to the phytoestrogen genistein at environmentally relevant doses. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:798–806. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Phelps JY, Gerrish KE, Williams CJ. Permanent oviduct posteriorization following neonatal exposure to the phytoestrogen genistein. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1575–1582. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallela K, Heinonen K, Saloniemi H. Plant oestrogens; the cause of decreased fertility in cows. A case report. Nord Vet Med. 1984;36:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao YC, Zhou C, Sherman M, Laughton CA, Chen S. Molecular basis of the inhibition of human aromatase (estrogen synthetase) by flavone and isoflavone phytoestrogens: A site-directed mutagenesis study. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:85–92. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9810685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel BA, Eddy KB, Cho S, Gangrade BK, May JV. Purified human alpha fetoprotein inhibits growth factor-stimulated estradiol production by porcine granulosa cells in monolayer culture. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3715–3717. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1375908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim SH, Huh K, Kim Y, Joung H, Park MJ. High serum isoflavone concentrations are associated with the risk of precocious puberty in Korean girls. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:831–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korach KS, McLachlan JA. The role of the estrogen receptor in diethylstilbestrol toxicity. Arch Toxicol Suppl. 1985;8:33–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69928-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouki T, Kishitake M, Okamoto M, Oosuka I, Takebe M, Yamanouchi K. Effects of neonatal treatment with phytoestrogens, genistein and daidzein, on sex difference in female rat brain function: estrous cycle and lordosis. Horm Behav. 2003;44:140–145. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouki T, Okamoto M, Wada S, Kishitake M, Yamanouchi K. Suppressive effect of neonatal treatment with a phytoestrogen, coumestrol, on lordosis and estrous cycle in female rats. Brain Res Bull. 2005;64:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SH, Kang MJ, Huh JS, Ha KW, Lee JR, Lee SK, Lee BS, Han IH, Lee MS, Lee MW, et al. Comparison of oral bioavailability of genistein and genistin in rats. Int J Pharm. 2007;337:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labinskyy N, Csiszar A, Veress G, Stef G, Pacher P, Oroszi G, Wu J, Ungvari Z. Vascular dysfunction in aging: potential effects of resveratrol, an anti-inflammatory phytoestrogen. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:989–996. doi: 10.2174/092986706776360987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JR, Faber KA, Ayyash L, Hughes CL., Jr The effect of prenatal exposure to the phytoestrogen genistein on sexual differentiation in rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;208:60–66. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tollefsbol TO. Impact on DNA methylation in cancer prevention and therapy by bioactive dietary components. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:2141–2151. doi: 10.2174/092986710791299966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorand T, Vigh E, Garai J. Hormonal action of plant derived and anthropogenic non-steroidal estrogenic compounds: phytoestrogens and xenoestrogens. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:3542–3574. doi: 10.2174/092986710792927813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losa SM, Todd KL, Sullivan AW, Cao J, Mickens JA, Patisaul HB. Neonatal exposure to genistein adversely impacts the ontogeny of hypothalamic kisspeptin signaling pathways and ovarian development in the peripubertal female rat. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. Endocrine disruptors in female reproductive tract development and carcinogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Naftolin F. Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science. 1981;211:1294–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.6163211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukura H, Aisaki K, Igarashi K, Matsushima Y, Kanno J, Muramatsu M, Sudo K, Sato N. Genistein promotes DNA demethylation of the steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) promoter in endometrial stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlock KL, Branham WS, Sheehan DM. Effects of coumestrol and equol on the developing reproductive tract of the rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995a;208:67–71. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlock KL, Branham WS, Sheehan DM. The effects of phytoestrogens on neonatal rat uterine growth and development. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995b;208:307–313. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlock KL, Forrester TM, Sheehan DM. Progesterone and estradiol interaction in the regulation of rat uterine weight and estrogen receptor concentration. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;205:146–153. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan SR, Khan O, Nash M. Competitive binding of xenobiotic oestrogens to rat alpha-fetoprotein and to sex steroid binding proteins in human and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) plasma. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;112:89–95. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa S, Buchanan DL, Sato T, Ohta Y, Nishina Y, Iguchi T. Characterization of diethylstilbestrol-induced hypospadias in female mice. Anat Rec. 2002;266:43–50. doi: 10.1002/ar.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley FH, Axelsen A, Bennett D. Recovery of normal fertility after grazing on oestrogenic red clover. Aust Vet J. 1966;42:204–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1966.tb04690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton MS, Arisaka O, Miyake N, Morgan LD, Evans BA. Phytoestrogen concentrations in serum from Japanese men and women over forty years of age. J Nutr. 2002;132:3168–3171. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutsatsou P. The spectrum of phytoestrogens in nature: our knowledge is expanding. Hormones (Athens) 2007;6:173–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao T, Yoshimura S, Saito Y, Nakagomi M, Usumi K, Ono H. Reproductive effects in male and female rats of neonatal exposure to genistein. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15:399–411. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Banks EP, Bullock B, Jefferson WN. Uterine adenocarcinoma in mice treated neonatally with genistein. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4325–4328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Bullock BC, McLachlan JA. Uterine adenocarcinoma in mice following developmental treatment with estrogens: a model for hormonal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7677–7681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Hanson RB, Jefferson WN, Bullock BC, Haseman J, McLachlan JA. Increased tumors but uncompromised fertility in the female descendants of mice exposed developmentally to diethylstilbestrol. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1655–1663. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Hanson RB, Jefferson WN, Bullock BC, Haseman J, McLachlan JA. Proliferative lesions and reproductive tract tumors in male descendants of mice exposed developmentally to diethylstilbestrol. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1355–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Haseman J. Developmental exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) alters uterine response to estrogens in prepubescent mice: low versus high dose effects. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido Y, Yoshizawa K, Danbara N, Tsujita-Kyutoku M, Yuri T, Uehara N, Tsubura A. Effects of maternal xenoestrogen exposure on development of the reproductive tract and mammary gland in female CD-1 mouse offspring. Reprod Toxicol. 2004;18:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North K, Golding J. A maternal vegetarian diet in pregnancy is associated with hypospadias. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. BJU Int. 2000;85:107–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Banks E, Jefferson WN, Myers PH, Goulding DR, Williams CJ. Neonatal phytoestrogen exposure causes hypospadias in female mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mrd.21395. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JR, Herbst AL, Noller KL, Boggs DA, Troisi R, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hatch EE, Wise LA, Strohsnitter WC, Hoover RN. Urogenital abnormalities in men exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero: a cohort study. Environ Health. 2009;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Xia X, Feng Y, Jiang C, Cui Y, Huang Y. Exposure of juvenile rats to the phytoestrogen daidzein impairs erectile function in a dose-related manner in adulthood. J Androl. 2008;29:55–62. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.003392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Jameson JL. Minireview: transcriptional regulation of gonadal development and differentiation. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1035–1042. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters PH, Slimani N, van der Schouw YT, Grace PB, Navarro C, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Clavel-Chapelon F, Touillaud M, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Variations in plasma phytoestrogen concentrations in European adults. J Nutr. 2007;137:1294–1300. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Signaling, physiological functions and clinical relevance of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;89:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD, Judd HL, Young PE, Jones OW, Yen SS. Amniotic fluid androgens and estrogens in midgestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;45:755–761. doi: 10.1210/jcem-45-4-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Stormshak F. The ovine sexually dimorphic nucleus, aromatase, and sexual partner preferences in sheep. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AE, Marchionni L, Phillips TM, Miller RM, Hurley PJ, Simons BW, Salmasi AH, Schaeffer AJ, Gearhart JP, Schaeffer EM. Molecular effects of genistein on male urethral development. J Urol. 2011;185:1894–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y. Gonadal steroid action and brain sex differentiation in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:410–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Gosselin SJ, Welsh MB, Johnston JO, Balistreri WF, Kramer LW, Dresser BL, Tarr MJ. Dietary estrogens--a probable cause of infertility and liver disease in captive cheetahs. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)91006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Zimmer-Nechemias L, Cai J, Heubi JE. Exposure of infants to phytooestrogens from soy-based infant formula. Lancet. 1997;350:23–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanle EK, Xu W. Endocrine disrupting chemicals targeting estrogen receptor signaling: identification and mechanisms of action. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:6–19. doi: 10.1021/tx100231n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe RM, Martin B, Morris K, Greig I, McKinnell C, McNeilly AS, Walker M. Infant feeding with soy formula milk: effects on the testis and on blood testosterone levels in marmoset monkeys during the period of neonatal testicular activity. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1692–1703. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Parent S, Leblanc V, Asselin E. Resveratrol modulates the expression of PTGS2 and cellular proliferation in the normal rat endometrium in an AKT-dependent manner. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1045–1052. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.090076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, Zehr JL. Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman RJ. In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol: adverse effects on the reproductive tract and reproductive performance and male and female offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:905–921. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Ziegler EE, Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Macones GA, Stallings VA, Drulis JM, Nelson SE, Hanson SA. Exposure to soy-based formula in infancy and endocrinological and reproductive outcomes in young adulthood. JAMA. 2001;286:807–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetsugi M, Su L, Karlsberg K, Yuan YC, Chen S. Flavone and isoflavone phytoestrogens are agonists of estrogen-related receptors. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:981–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AW, Hamilton P, Patisaul HB. Neonatal agonism of ERbeta impairs male reproductive behavior and attractiveness. Horm Behav. 2011;60:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme MR, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. Drug transfer and metabolism by the human placenta. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:487–514. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KA, Walker M, Morris K, Greig I, Mason JI, Sharpe RM. Infant feeding with soy formula milk: effects on puberty progression, reproductive function and testicular cell numbers in marmoset monkeys in adulthood. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:896–904. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang WY, Newbold R, Mardilovich K, Jefferson W, Cheng RY, Medvedovic M, Ho SM. Persistent hypomethylation in the promoter of nucleosomal binding protein 1 (Nsbp1) correlates with overexpression of Nsbp1 in mouse uteri neonatally exposed to diethylstilbestrol or genistein. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5922–5931. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LU, Boucher BA, Liu Z, Cotterchio M, Kreiger N. Phytoestrogen content of foods consumed in Canada, including isoflavones, lignans, and coumestan. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:184–201. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5402_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tou JC, Chen J, Thompson LU. Flaxseed and its lignan precursor, secoisolariciresinol diglycoside, affect pregnancy outcome and reproductive development in rats. J Nutr. 1998;128:1861–1868. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.11.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezu T, Yamanouchi H, Iida Y, Miura M, Tomooka Y. Follistatin-like-1, a diffusible mesenchymal factor determines the fate of epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4601–4606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes-Dapena MA. The development of the uterus in late fetal life, infancy, and childhood. In: Norris HJ, editor. The Uterus (International Academy of Pathology Monograph Series) Melbourne, FL: Krieger Pub Co.; 1973. pp. 40–67. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin-Blasini L, Blount BC, Caudill SP, Needham LL. Urinary and serum concentrations of seven phytoestrogens in a human reference population subset. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2003;13:276–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]