Abstract

Leukemia stem cells (LSCs), which constitute a minority of the tumor bulk, are functionally defined on the basis of their ability to transfer leukemia into an immunodeficient recipient animal. The presence of LSCs has been demonstrated in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), of which ALL with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+). The use of imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), as part of front-line treatment and in combination with cytotoxic agents, has greatly improved the proportions of complete response and molecular remission and the overall outcome in adults with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL. New challenges have emerged with respect to induction of resistance to imatinib via Abelson tyrosine kinase mutations. An important recent addition to the arsenal against Ph+ leukemias in general was the development of novel TKIs, such as nilotinib and dasatinib. However, in vitro experiments have suggested that TKIs have an antiproliferative but not an antiapoptotic or cytotoxic effect on the most primitive ALL stem cells. None of the TKIs in clinical use target the LSC. Second generation TKI dasatinib has been shown to have a more profound effect on the stem cell compartment but the drug was still unable to kill the most primitive LSCs. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) remains the only curative treatment available for these patients. Several mechanisms were proposed to explain the resistance of LSCs to TKIs in addition to mutations. Hence, TKIs may be used as a bridge to SCT rather than monotherapy or combination with standard chemotherapy. Better understanding the biology of Ph+ ALL will open new avenues for effective management. In this review, we highlight recent findings relating to the question of LSCs in Ph+ ALL.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Philadelphia chromosome, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Leukemia stem cells, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decades, it has been recognized that tumors contain a subpopulation of cells with biological features that are reminiscent of stem cells[1]. The modern concept of “cancer stem cell” was promoted by John Dick and colleagues, who showed that cells with the ability to transfer human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) to NOD/SCID mice are frequently found exclusively in the CD34+ CD38- compartment[2,3]. Stem cells modulate tissue formation, maintenance and repair, based on a complex interaction of cell-autonomous and cell-no autonomous regulatory mechanisms[4]. Classically, these cells could be subdivided into more or less primitive subpopulations that are organized in a hierarchy reminiscent of the normal hematopoietic system. A slow cycling fraction of cells is generating a fast cycling fraction. However, an alternative hypothesis predicts that all tumor cells have the potential to self-renew and recapitulate the tumor but with a low probability that any tumor cell enters the cell cycle and finds a permissive environment[5]. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) defines a heterogeneous group of leukemias that express predominantly lymphoid cell surface markers[6]. Although proof of the existence of a stem cell-like population maintaining ALL has been elusive, subpopulations with primitive phenotypes have been reported in clinical ALL samples. Response to therapy is related to biological characteristics of the cell of origin and to the primitive stem cell-like population. Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) ALL is regarded as a specific entity. The initial treatment of Ph+ ALL has recently been dramatically changed by the introduction of Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). However, cure depends on the eradication of the leukemia stem cell (LSC). This review will discuss current treatment and evidence for an ALL stem cell in Ph+ ALL and its relationship with new therapeutic advances based on TKI therapy in this disease.

Ph (BREAKPOINT CLUSTER REGION-ABELSON TYROSINE KINASE)-POSITIVE B-LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKEMIA

In 1960, Nowell and Hungerford described a small G group chromosome, the Ph[7]. The Ph+ chromosome is the most frequent cytogenetic abnormality in human leukemia and can be detected in a range of 2% to 5% of children with ALL[8] and 20% to 40% of adults with ALL[9]. The proportion of Ph+ ALL cases increases with age[10] but in very old persons the proportion decreases again[9]. This t(9;22) translocation leads to a head-to-tail fusion of the Abelson tyrosine kinase (ABL) proto-oncogene from chromosome 9 with a 5’ half of the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) sequences on chromosome 22[11]. Transcription of BCR-ABL results either in a 8.5-kilobase (kb) messenger RNA (mRNA) that codes for a 210-kb protein when ABL moves to the major BCR (M-BCR) or in a 7.5-kb RNA encoding a 190-kb protein when it moves to the M-BCR[12]. BCR-ABL proteins demonstrate enhanced tyrosine kinase activity compared to the normal ABL gene product. P190 exhibits a higher transforming potential than p210 in animal models[13]. The p190 protein is usually found in 2/3 of adults with de novo Ph+ ALL[14,15]. The constitutively active tyrosine kinase product BCR-ABL provides a pathogenetic explanation for the initiation of Ph+ ALL as well as a critical molecular therapeutic target. Both possible chimeric mRNAs (p210 and p190) can be sensitively and specifically detected by the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)[16]. Recent reports suggest that the expression of the p190 transcript was associated with a significant increase in the risk of relapse[14]. BCR-ABL expression in hematopoietic cells is known to induce resistance to apoptosis, growth factor independence, as well as alterations in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions[17]. Clinically, patients present with a variable white blood cell count and have an increased risk of developing meningeal leukemia during the course of treatment, although central nervous system leukemia was not significantly more frequent (5%) at diagnosis[10]. Ph+ ALL are found almost exclusively among B-cell linage ALL (CD10+ precursor B-cell ALL). Leukemic cells often present surface expression of CD34 antigen (89%), and frequent expression of myeloid markers (15% to 20%)[14]. Additional chromosome abnormalities have been observed in 70% of Ph+ ALL patients[18], including mainly 9p abnormalities, monosomy 7 or hyperdiploid karyotypes > 50. CD117 is typically not expressed and only rarely is t(9;22) seen in T-lymphoblastic leukemia. Patients with t(9;22) classically have a poor prognosis.

CURRENT THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES IN Ph+ ALL

TKIs

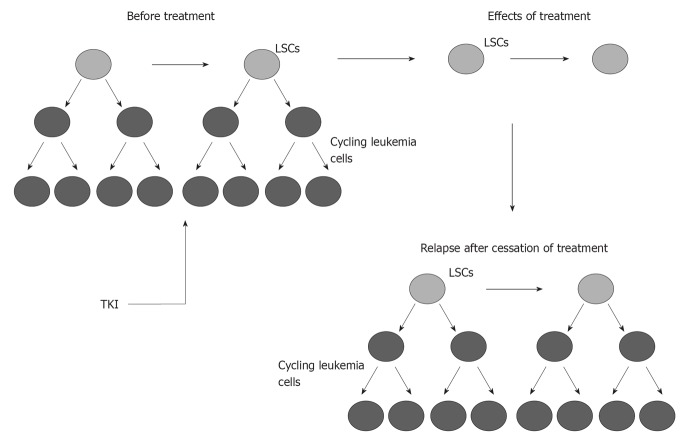

The Ph+ chromosome has historically been the worst prognostic indicator in ALL. The initial treatment of Ph+ ALL has been dramatically changed by the introduction of ABL TKIs. Imatinib mesylate, 2-phenylamino pyrimidine, binds to the ABL-ATP site in a competitive manner, stabilizing ABL in its inactive conformation and inhibiting its tyrosine kinase activity. Following initial studies showing that use of imatinib mesylate as a single agent in Ph+ ALL yielded potential responses but was unlikely to be sufficient for long-term disease control, the efficacy of imatinib was explored as front-line treatment combined with chemotherapy, either concurrently (simultaneous administration) or sequentially (alternating administration)[19-23]. Imatinib was given concurrently at 400 mg/d for the first 14 d with each cycle of the hyperCVAD regimen[19]. In this study, complete remission (CR) rate was 96%. There was no unexpected toxicity related to the addition of imatinib. Similarly, encouraging data were reported by the Japanese Adult Leukemia Study Group, in which imatinib was started after 1 wk of induction therapy and then coadministered with chemotherapy during the remainder of a standard induction[20]. The CR rate was 96% (median time to CR: 28 d) and a remarkably high molecular response rate became apparent as early as 2 mo after starting treatment. Transplant candidates had a better chance of receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) with imatinib-combined regimen. Alternating and concurrent imatinib-chemotherapy combinations were compared by the German Multicenter ALL (GMALL) trial in two sequential patient cohorts[24]. Efficacy analyses based on BCR-ABL transcript levels showed a clear advantage of the simultaneous over the alternating schedule, with 52% of patients achieving PCR negativity (vs 19%). Several approaches using imatinib-based induction therapy have been explored for elderly patients. Monotherapy with imatinib was explored in elderly patients, who had an extremely poor outcome with chemotherapy alone. Imatinib with or without corticosteroids resulted in high CR rates of 90% to 100%[22,23,25]. With relatively minimal use of imatinib (600 mg/d for phase 2 induction), the Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia showed a higher CR rate compared with historical controls[25]. Similar results were reported by the Italian group using continuous administration of imatinib (800 mg) only combined with prednisone[23]. The German group (GMALL) conducted a randomized study comparing induction therapy with single-agent imatinib with standard induction chemotherapy[22]. Response rate was better with single-agent imatinib (96% vs 50%). Achievement of molecular remission was associated with longer disease-free survival. Unfortunately, imatinib resistance developed rapidly and was quickly followed by disease progression. Disease recurrence was related to a high rate of ABL mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD)[26]. Data from the United Kingdom Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (UKALL)XII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 2993 study, in which imatinib (600 mg) was started with phase 2 induction, did not initially provide clear evidence that imatinib alters the outcome of the disease[27] but finally showed an advantage for the imatinib arm[28]. Studies demonstrated that a quiescent population of LSCs with BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations, detectable prior to initiation of imatinib therapy, gives rise to leukemic cells that persist because they are inherently resistant to imatinib (Figure 1)[29]. Quiescent LSCs also have high BCR-ABL transcript levels.

Figure 1.

Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitor on Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia and their stem cell counterparts. Therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) results in the depletion of cycling leukemia cells (of which progenitor cells) without eliminating the Leukemia stem cells (LSCs), then the latter can regenerate the tumor after that therapy is halted. This seems to explain why TKI treatment needs to be chronic and why future drug development needs to be focused on agents that stike at the core of tumors by destroying stem cells.

New strategies using second generation TKIs are being developed to overcome resistance to imatinib. A recent phase II study combining the hyperCVAD regimen with dasatinib (50 mg bid) for the first 14 d of each cycle showed CR achievement in 93% of newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL, with molecular remissions observed even after the first cycle[30]. In a series combining dasatinib (70 mg bid) with only steroids, CR was achieved in all cases with a very marked clearance of blasts already at day 22[31]. Nilotinib as monotherapy also appeared to have promising activity and a favorable safety profile[32]. Its use in combination with chemotherapy is currently tested. Even 20-fold more potent BCR-ABL inhibition with nilotinib did not induce apoptosis of quiescent CD34+ cells nor did inhibition with a dual SRC-ABL kinase inhibitor[33].

The appearance of mutations which are most probably but not exclusively related to resistance led to avoiding induction drugs, such as anthracyclines or alkylating agents, which can cause mutational resistance and preference for methotrexate, cytarabine and asparaginase. Such a trial in older adult patients led to high CR rate and improved survival[34].

The role of hematopoietic SCT in Ph+ ALL

Allogeneic SCT from a related or unrelated donor has historically been the standard form of consolidation in Ph+ ALL, with 27% to 65% of long-term survival in patients grafted in first CR[28,35,36]. The aggressivity of the disease often resulted in a rapid relapse prior to transplant and only 30% to 50% of patients in first remission eventually underwent allogeneic SCT. The relapse-free survival advantage of the patient developing acute or chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) and the description of PCR conversion after developing GVHD have suggested that Ph+ ALL was particularly sensitive to the graft-vs-leukemia effect[37]. The recent incorporation of TKIs into standard ALL therapy has resulted in improved remission induction rates of 95%, with 50% to 70% of patients achieving molecular negativity. More patients were able to receive SCT in first CR, resulting in improved overall survival rates of 43% to 78% with 1-3 years of follow-up[20,21,24,38,39]. The combination of imatinib and multiagent chemotherapy did not result in increased toxicity and did not unfavorably affect allogeneic SCT. The molecular detection of the BCR-ABL fusion mRNA by PCR has been shown to be an effective method for monitoring disease. BCR-ABL levels before transplantation are prognostic. Patients who are in remission morphologically and molecularly have the best outcome, whereas those who are molecularly positive, although still in conventional remission, suffer a relatively higher relapse rate[40]. Results after allogeneic SCT may be improved by the use of imatinib as maintenance. Patients remaining BCR-ABL positive after allogeneic SCT can achieve molecular remission with imatinib and survive long-term. Thus, post-transplant imatinib can reduce the relapse rate. However, imatinib should not be given before 6 to 8 wk after transplantation to avoid cumulative toxicity. Duration of TKI maintenance remains open, either for 2 years or stopped after repeated minimal residual disease negativity.

RESISTANCE TO TKIs

The effectiveness of imatinib alone is limited by the relatively frequent development of resistance. Mechanisms that have been implicated in resistance include rapid drug efflux[41], amplification of the BCR-ABL gene[42], reduced binding affinity of imatinib to the ATP-binding site due to genetic changes[43], and BCR-ABL independence resulting from secondary transforming events[44]. As in chronic phase myeloid leukemia (CML), secondary resistance in Ph+ ALL is frequently associated with point mutations in the TKD of BCR-ABL[43,45]. Among these resistance mechanisms, dose escalation of imatinib or the use of more potent ABL inhibitors could resolve the first events, while only the use of multitargeted inhibitors could restore sensitivity in the other mechanisms. ABL TKD mutations generally are comprised of two categories: mutations that directly impede contact between imatinib and Bcr-Abl, such as the gatekeeper mutations T315I and F317L[46], and mutations that alter the spacial conformation of the BCR-ABL protein by affecting the P-loop containing the ATP-binding pocket and/or the activating loop[45]. To date, more than 50 ABL TKD mutations have been identified. Data on the frequency and incidence of mutations in Ph+ ALL have been relatively sparse. However, the German group showed that ABL mutations could be detected in nearly 40% of patients at the time of diagnosis in imatinib-naïve patients (P-loop mutations in 80% and T314I mutation in 17%)[26]. At the time of recurrence, ABL mutations were found in 84% of cases (P-loop mutations in 57% and T315I mutation in 19%). The mutated clone then consistently represented the dominant population. Almost all patients with mutant BCR-ABL detected before imatinib therapy had the same mutation at relapse. Remission duration did not differ significantly between patients with or without a detectable early mutation. Imatinib initially suppressed the dominant, unmutated leukemic population, without simultaneous outgrowth of the pre-existing mutant subclones. However, these pre-existing mutant clones almost invariably give rise to eventual relapse. To significantly improve outcome, it would be necessary to eliminate clones harboring mutations during the early phase of treatment, before they have acquired additional resistance mechanisms. The cause for relapse has been related to TKI resistance of the LSCs and/or immune tolerance of leukemic cells. In vitro experiments have suggested that TKIs have an antiproliferative, but not a proapoptotic or cytotoxic effect on the most primitive Ph+ stem cells (CD34+ CD38- cells)[47,48]. Second generation TKI dasatinib has been shown to have a more profound effect on the stem cell compartment when compared to imatinib or nilotinib, but the drug was still unable to kill the most primitive CD34+ CD38- LSCs in vitro[48]. However, recent analyses in CML with successful TKI therapy have demonstrated the eradication of most Ph+ CD34+ CD38- cells from the central bone marrow[49]. Selective chemical inhibition of Src family kinases decreases growth and expression of stem cell genes, including Oct3/4 and Nanog, involved in self renewal and survival of LSCs[50].

Resistance attributable to kinase domain mutations can lead to relapse despite the development of second-generation compounds, including dasatinib and nilotinib. Despite these therapeutic options, the cross-resistant BCR-ABL T315I mutation remains a major clinical challenge. The first evaluations of AP24534 present this drug as a potent multi-targeted kinase inhibitor active against T315I and all other BCR-ABL mutants[51-54]. AP24534 could be the next treatment of choice in hematological malignancies with Ph+ chromosome, particularly Ph+ ALL known for its frequent occurrence of T315I mutation. However, its potential action on LSCs is still unknown.

LSCs IN ALL

ALL defines a heterogeneous group of leukemias. Reports assessing the cell of origin have been contradictory. Discrepancies may be related to the heterogeneity of the disease. In ALL and other malignancies, compelling research suggests that a population of cancer stem cells is able to regenerate or self-renew, resulting in therapeutic resistance and disease progression. A number of studies indicate that quiescent LSCs are resistant to therapies that target rapidly dividing cells. However, the marked differences in response to therapy could be related to the different characteristics of the cell of origin, and to the existence and relative importance of a primitive LSC population for a given ALL subtype. Rearrangements of the T-cell receptor or the immunoglobulin heavy chain genes support the theory that T- and B-lineage ALL originate in cells already committed to the T- or B-cell lineages. In vivo xenotransplantation model showed that CD34+ CD38+ CD19+ and CD34+ CD38- CD19+ cells from pediatric patients with B-ALL initiate B-ALL in primary recipients, whereas the recipients of CD34+ CD38- CD10- CD19- cells showed normal human hematopoietic repopulation[55]. Furthermore, transplantation of CD34+ CD38+ CD19+ cells resulted in the development of B-ALL in secondary recipients, demonstrating self-renewal capacity. In T-ALL, cells capable of long-term proliferation have been demonstrated in the CD34+ CD4- and CD34+ CD7- cell subfractions[56]. In TEL/AML1 rearranged ALL, the earliest population that consistently conferred leukemia to immunocompromised mice has been defined as CD34+ CD38– CD19+[57,58]. Engraftment was also reported from a more differentiated CD34– CD19+ subpopulation[59], questioning the existence of a strict hierarchy in this type of ALL. Normal individuals may have B cells harboring a TEL/AML1 fusion that never undergo leukemic transformation, suggesting a ‘multi-hit’ model of leukemogenesis, in which TEL/AML1-positive precursor cells constitute a pre-leukemic pool[60]. In hyperdiploid ALL, it appears that some cases have leukemia-initiating activity in populations consistent with later mid-stage B-cell development[61]. Only CD34+ CD10– or CD34+ CD19– cells resulted in reliable leukemic engraftment in ALL samples with normal karyotype[62]. MLL-AF4-positive cells were reported in high frequency in the CD34+ CD19– compartment. These cells, carrying an immature phenotype, suggest a developmental stage prior to commitment to the lymphoid lineage[59]. The microenvironment may play an important role in determining lineage fate in MLL-rearranged leukemias[63,64].

LSCs IN BCR-ABL-POSITIVE ALL

CD34+ stem cells cannot be effectively killed by BCR-ABL kinase inhibitor imatinib treatment both in vitro and in vivo[47,65]. BCR-ABL transcripts are still detectable in CD34+ cells after a long-term treatment with imatinib[65], suggesting that these LSCs cannot be eradicated through inhibiting BCR-ABL kinase activity. Similarly, imatinib does not eradicate LSCs in mice[66]. These results indicate that some unknown pathways contribute to the maintenance of survival and self-renewal of LSCs. The LSCs seem to be biologically distinct from their more differentiated progeny. Therefore, the agents acting against the more mature blasts will not be as efficient in eradicating the LSCs. Divisional asymmetry and environmental asymmetry are two mechanisms responsible for asymmetric cell division. In the first case, specific cell-fate determinants redistribute unequally among daughter cells, of which one receives these determinants, while the other proceeds to differentiation. In the other case, a LSC would first undergo a symmetric division. However, only one cell remains in the bone marrow niche and conserves stem cell fate, while the other cell enters a different microenvironment and subsequently produces signals initiating differentiation. Identification of novel genes that play critical role in regulating the function of LSCs can contribute to the development of new therapeutic strategies through targeting LSCs.

Given the central role that LSCs play in leukemia maintenance, studies have focused on identifying pathways of proliferation, self-renewal and survival that are differentially active in LSCs rather than normal hematopoetic stem cells. The expression of p190 or p210 BCR-ABL fusion forms is sufficient to cause leukemia in animal models[67]. The JAK-STAT, Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK, PI3K-AKT, c-Myc, SAPK-JNK and NF-κB pathways are among the pathways activated by BCR-ABL. Those pathways are involved in cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. Ph+ ALL is also characterized by a high degree of genomic instability that is induced by the BCR-ABL protein, as demonstrated by the increased frequency of DNA insertions and deletions present in BCR-ABL pre-leukemic mice[68]. Ph+ ALL often presents aberrant splicing of key genes in lymphoid development, such as BTK and SLP-65, and deleterious mutations of IKZF1, a gene that encodes the zinc-finger transcription factor Ikaros[69,70]. The aberrant splicing of SLP-65 and BTK in B-cell precursors results in shorter transcripts that halt lymphoid maturation[71]. The deletion of exons of IKZF1 results in a dominant negative form of Ikaros that lacks the DNA-binding domain. This mutated form halts B-cell differentiation and contributes to the expression of some myeloid specific genes[70]. Its overexpression may also contribute to resistance to TKIs[72]. A common additional mutation in Ph+ ALL is the deletion of 9p21, compromising the INK4A-ARF gene[73]. The activation of p14ARF induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through p53 activation and Arf-null BCR-ABL+ cells induce more severe leukemia in irradiated mice recipients. Another particularity of Ph+ ALL is the dependence of BCR-ABL transformation on Src kinases that do not appear to be required for the induction of CML[74]. However, CML progression to lymphoid blast crisis may also depend on Src kinases as lymphoid blast crisis cells are also dependent on Lyn for survival, to a higher extent than myeloid blast crisis CML cells, suggesting a lineage-specific signaling pathway or mechanism[75].

In contrast with CML, if Ph+ ALL is lineage restricted, one should find the Ph+ only in lymphoid cells. However, original studies in patients did not yield such a clear cut distinction. Involvement of the myeloid compartment has been reported for Ph+ ALL[76]. The Ph could be detected in both mature myeloid cells and myeloid colony-forming units, suggesting that at least in some patients the leukemia-initiating event occurs in a primitive cell that has not already undergone lineage commitment[77]. An alternative explanation would be that BCR-ABL ALL blasts reacquire specific lineage promiscuity. Recent functional studies conclude that LSC in Ph+ ALL is a primitive cell lymphoid that is restricted as it will not originate from myeloid or erythroid colonies, although the studies differ on the characterization of this LSC. The CD34+ CD38- CD19- cell compartment has been shown to be involved in patients with p210 BCR-ABL ALL but not in those with p190 BCR-ABL ALL[58]. The p210 BCR-ABL transcript could also be identified in CD34+ CD33+ and CD34- CD33+ myeloid precursors, which was not the case for the p190 transcript. However, CD34+ CD38- CD19- p210-positive cells did not induce leukemia in NOD/SCID mice. This contrasts with other results showing NOD/SCID engrafting leukemic cells only in the CD34+ CD38- subfraction and not in the CD34+ CD38+ cells[78]. The CD34+ CD19- cells have also been shown as the most undifferentiated leukemia progenitors in patients with Ph+ ALL but they did not differentiate into myeloid colonies[79].

CONCLUSION

By definition, cure of leukemia requires eradication or transcriptional control of LSCs. To date, little is known regarding the efficacy of TKIs in the longer term. Although reduction in the number of LSCs by TKI therapy is feasible, quiescent LSCs are likely to survive to TKIs combined with chemotherapy. Allogeneic transplantation remains therefore the treatment of choice, preferably in first CR. However, a more complete understanding of the biology of Ph+ chromosome is needed in order to cure patients who cannot receive allogeneic SCT. Patients with Ph+ ALL may be heterogeneous. The determination of residual populations of quiescent Ph+ cells is important for evaluating response in treated patients. Specific inhibition of LSCs in Ph+ ALL is a suitable approach to developing a cure for this disease in the future. Several gene products required by LSCs have been shown to be potential targets for inhibiting LSCs. The mechanisms by which involved pathways regulate the function of LSCs need to be further studied.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Rajesh Ramasamy, PhD, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia, UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.McCulloch EA, Howatson AF, Buick RN, Minden MD, Izaguirre CA. Acute myeloblastic leukemia considered as a clonal hemopathy. Blood Cells. 1979;5:261–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas X. Emerging drugs for adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2005;10:591–617. doi: 10.1517/14728214.10.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. Chromosome studies on normal and leukemic human leukocytes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1960;25:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlieben S, Borkhardt A, Reinisch I, Ritterbach J, Janssen JW, Ratei R, Schrappe M, Repp R, Zimmermann M, Kabisch H, et al. Incidence and clinical outcome of children with BCR/ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). A prospective RT-PCR study based on 673 patients enrolled in the German pediatric multicenter therapy trials ALL-BFM-90 and CoALL-05-92. Leukemia. 1996;10:957–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Blood. 1996;87:3135–3142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radich JP. Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:21–36. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartram CR, de Klein A, Hagemeijer A, van Agthoven T, Geurts van Kessel A, Bootsma D, Grosveld G, Ferguson-Smith MA, Davies T, Stone M. Translocation of c-ab1 oncogene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306:277–280. doi: 10.1038/306277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan LC, Karhi KK, Rayter SI, Heisterkamp N, Eridani S, Powles R, Lawler SD, Groffen J, Foulkes JG, Greaves MF. A novel abl protein expressed in Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 1987;325:635–637. doi: 10.1038/325635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lugo TG, Pendergast AM, Muller AJ, Witte ON. Tyrosine kinase activity and transformation potency of bcr-abl oncogene products. Science. 1990;247:1079–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.2408149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dombret H, Gabert J, Boiron JM, Rigal-Huguet F, Blaise D, Thomas X, Delannoy A, Buzyn A, Bilhou-Nabera C, Cayuela JM, et al. Outcome of treatment in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia--results of the prospective multicenter LALA-94 trial. Blood. 2002;100:2357–2366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gleissner B, Gökbuget N, Bartram CR, Janssen B, Rieder H, Janssen JW, Fonatsch C, Heyll A, Voliotis D, Beck J, et al. Leading prognostic relevance of the BCR-ABL translocation in adult acute B-lineage lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective study of the German Multicenter Trial Group and confirmed polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood. 2002;99:1536–1543. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurer J, Janssen JW, Thiel E, van Denderen J, Ludwig WD, Aydemir U, Heinze B, Fonatsch C, Harbott J, Reiter A. Detection of chimeric BCR-ABL genes in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by the polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91706-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O’Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. The biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:164–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieder H, Ludwig WD, Gassmann W, Maurer J, Janssen JW, Gökbuget N, Schwartz S, Thiel E, Löffler H, Bartram CR, et al. Prognostic significance of additional chromosome abnormalities in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:678–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DA, Faderl S, Cortes J, O’Brien S, Giles FJ, Kornblau SM, Garcia-Manero G, Keating MJ, Andreeff M, Jeha S, et al. Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia with hyper-CVAD and imatinib mesylate. Blood. 2004;103:4396–4407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanada M, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, Akiyama H, Usui N, Yagasaki F, Kobayashi T, Ueda Y, Takeuchi M, Miyawaki S, et al. High complete remission rate and promising outcome by combination of imatinib and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a phase II study by the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:460–466. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, Lee JH, Seol M, Lee YS, Kim WK, Lee JS, Seo EJ, Jang S, et al. Clinical effect of imatinib added to intensive combination chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1509–1516. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottmann OG, Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Giagounidis A, Stelljes M, Dührsen U, Schmalzing M, Wunderle L, Binckebanck A, Hoelzer D. Imatinib compared with chemotherapy as front-line treatment of elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ALL) Cancer. 2007;109:2068–2076. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vignetti M, Fazi P, Cimino G, Martinelli G, Di Raimondo F, Ferrara F, Meloni G, Ambrosetti A, Quarta G, Pagano L, et al. Imatinib plus steroids induces complete remissions and prolonged survival in elderly Philadelphia chromosome-positive patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia without additional chemotherapy: results of the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) LAL0201-B protocol. Blood. 2007;109:3676–3678. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, Beelen DW, Beck J, Stelljes M, Bornhäuser M, Reichle A, Perz J, Haas R, et al. Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) Blood. 2006;108:1469–1477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delannoy A, Delabesse E, Lhéritier V, Castaigne S, Rigal-Huguet F, Raffoux E, Garban F, Legrand O, Bologna S, Dubruille V, et al. Imatinib and methylprednisolone alternated with chemotherapy improve the outcome of elderly patients with Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the GRAALL AFR09 study. Leukemia. 2006;20:1526–1532. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeifer H, Wassmann B, Pavlova A, Wunderle L, Oldenburg J, Binckebanck A, Lange T, Hochhaus A, Wystub S, Brück P, et al. Kinase domain mutations of BCR-ABL frequently precede imatinib-based therapy and give rise to relapse in patients with de novo Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) Blood. 2007;110:727–734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-052373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Luger SM, Marks DI, McMillan AK, Rowe JM, Tallman MS, Goldstone AH. Does imatinib change the outcome in Philapdelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults Data from the UKALLXII/ECOG2993 study (Abstract 8) Blood. 2007;110:10a. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Richards SM, Buck G, Moorman AV, Durrant IJ, Marks DI, McMillan AK, Litzow MR, Lazarus HM, et al. Prospective outcome data on 267 unselected adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia confirms superiority of allogeneic transplantation over chemotherapy in the pre-imatinib era: results from the International ALL Trial MRC UKALLXII/ECOG2993. Blood. 2009;113:4489–4496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamieson CH, Ailles LE, Dylla SJ, Muijtjens M, Jones C, Zehnder JL, Gotlib J, Li K, Manz MG, Keating A, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:657–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravandi F, O’Brien S, Thomas D, Faderl S, Jones D, Garris R, Dara S, Jorgensen J, Kebriaei P, Champlin R, et al. First report of phase 2 study of dasatinib with hyper-CVAD for the frontline treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2070–2077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foa R, Vignetti M, Vitale A, Meloni G, Guarini A, De Propris S, Elia L, Cimino G, Luppi M, Castagnola C, et al. Dasatinib as front-line monotherapy for the induction treatment of Aadult and elderly Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients: interim analysis of the GIMEMA prospective study LAL1205 (Abstract) Blood. 2007;110:10a. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottmann OG, Larson RA, Kantarjian HM, le Coutre P, Baccarani M, Haque A, Gallagher N, Giles F. Nilotinib in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) who are resistant or intolerant to imatinib (Abstract) Blood. 2007;110:2815. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jørgensen HG, Allan EK, Jordanides NE, Mountford JC, Holyoake TL. Nilotinib exerts equipotent antiproliferative effects to imatinib and does not induce apoptosis in CD34+ CML cells. Blood. 2007;109:4016–4019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rousselot P, Cayuela JM, Reche C, Leguay T, Salanoubat C, Witz F, Alexis M, Janvier M, Hunault M, Agape P, et al. Dasatinib (Sprycel®) and chemotherapy for first-line treatment in elderly patients with de novo Philadelphia positive ALL: Results of the first 22 patients included in the EWALL-Ph-01 trial (on behalf of the European Working Group on Adult ALL (EWALL)) (Abstract 2920) Blood. 2008;112:1004–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Witte T, Awwad B, Boezeman J, Schattenberg A, Muus P, Raemaekers J, Preijers F, Strijckmans P, Haanen C. Role of allogenic bone marrow transplantation in adolescent or adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma in first remission. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:767–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder DS, Nademanee AP, O’Donnell MR, Parker PM, Stein AS, Margolin K, Somlo G, Molina A, Spielberger R, Kashyap A, et al. Long-term follow-up of 23 patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplant in first complete remission. Leukemia. 1999;13:2053–2058. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cornelissen JJ, Carston M, Kollman C, King R, Dekker AW, Löwenberg B, Anasetti C. Unrelated marrow transplantation for adult patients with poor-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: strong graft-versus-leukemia effect and risk factors determining outcome. Blood. 2001;97:1572–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Towatari M, Yanada M, Usui N, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, Takeuchi M, Yagasaki F, Kawai Y, Miyawaki S, Ohtake S, et al. Combination of intensive chemotherapy and imatinib can rapidly induce high-quality complete remission for a majority of patients with newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:3507–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Labarthe A, Rousselot P, Huguet-Rigal F, Delabesse E, Witz F, Maury S, Réa D, Cayuela JM, Vekemans MC, Reman O, et al. Imatinib combined with induction or consolidation chemotherapy in patients with de novo Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the GRAAPH-2003 study. Blood. 2007;109:1408–1413. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goulden N, Bader P, Van Der Velden V, Moppett J, Schilham M, Masden HO, Krejci O, Kreyenberg H, Lankester A, Révész T, et al. Minimal residual disease prior to stem cell transplant for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:24–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas J, Wang L, Clark RE, Pirmohamed M. Active transport of imatinib into and out of cells: implications for drug resistance. Blood. 2004;104:3739–3745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, Hsu N, Paquette R, Rao PN, Sawyers CL. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293:876–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofmann WK, Komor M, Hoelzer D, Ottmann OG. Mechanisms of resistance to STI571 (Imatinib) in Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:655–660. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001625755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donato NJ, Wu JY, Stapley J, Gallick G, Lin H, Arlinghaus R, Talpaz M. BCR-ABL independence and LYN kinase overexpression in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells selected for resistance to STI571. Blood. 2003;101:690–698. doi: 10.1182/blood.V101.2.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Bubnoff N, Peschel C, Duyster J. Resistance of Philadelphia-chromosome positive leukemia towards the kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571, Glivec): a targeted oncoprotein strikes back. Leukemia. 2003;17:829–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blencke S, Zech B, Engkvist O, Greff Z, Orfi L, Horváth Z, Kéri G, Ullrich A, Daub H. Characterization of a conserved structural determinant controlling protein kinase sensitivity to selective inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2004;11:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham SM, Jørgensen HG, Allan E, Pearson C, Alcorn MJ, Richmond L, Holyoake TL. Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood. 2002;99:319–325. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Copland M, Hamilton A, Elrick LJ, Baird JW, Allan EK, Jordanides N, Barow M, Mountford JC, Holyoake TL. Dasatinib (BMS-354825) targets an earlier progenitor population than imatinib in primary CML but does not eliminate the quiescent fraction. Blood. 2006;107:4532–4539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mustjoki S, Rohon P, Rapakko K, Jalkanen S, Koskenvesa P, Lundán T, Porkka K. Low or undetectable numbers of Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemic stem cells (Ph(+)CD34(+)CD38(neg)) in chronic myeloid leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission after tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Leukemia. 2010;24:219–222. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Annerén C, Cowan CA, Melton DA. The Src family of tyrosine kinases is important for embryonic stem cell self-renewal. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31590–31598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang WS, Metcalf CA, Sundaramoorthi R, Wang Y, Zou D, Thomas RM, Zhu X, Cai L, Wen D, Liu S, et al. Discovery of 3-[2-(imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-3-yl)ethynyl]-4-methyl-N-{4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl}benzamide (AP24534), a potent, orally active pan-inhibitor of breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL) kinase including the T315I gatekeeper mutant. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4701–4719. doi: 10.1021/jm100395q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, Adrian LT, Zhou T, Huang WS, Xu Q, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortes J, Talpaz M, Deininger M, Shah N, Flinn IW, Mauro MJ, O'Hare T, Spinos N, Hu S, Berk L, et al. A phase 1 trial of oral AP24534 in patients with refractory chronic myeloid leukemia and other hematologic malignancies: first results of safety and clinical activity against T315I and resistant mutations (Abstract 643) Blood. 2009;114:264. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Talpaz M, Cortes JE, Deininger MW, Shah NP, Flinn IW, Mauro MJ, O'Hare T, Rivera V, Kantarjian H, Haluska FG. Phase I trial of AP24534 in patients with refractory chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and hematologic malignancies (Abstract 6511) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 Suppl:15s. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong Y, Yoshida S, Saito Y, Doi T, Nagatoshi Y, Fukata M, Saito N, Yang SM, Iwamoto C, Okamura J, et al. CD34+CD38+CD19+ as well as CD34+CD38-CD19+ cells are leukemia-initiating cells with self-renewal capacity in human B-precursor ALL. Leukemia. 2008;22:1207–1213. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cox CV, Martin HM, Kearns PR, Virgo P, Evely RS, Blair A. Characterization of a progenitor cell population in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:674–682. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hotfilder M, Röttgers S, Rosemann A, Jürgens H, Harbott J, Vormoor J. Immature CD34+CD19- progenitor/stem cells in TEL/AML1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are genetically and functionally normal. Blood. 2002;100:640–646. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castor A, Nilsson L, Astrand-Grundström I, Buitenhuis M, Ramirez C, Anderson K, Strömbeck B, Garwicz S, Békássy AN, Schmiegelow K, et al. Distinct patterns of hematopoietic stem cell involvement in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med. 2005;11:630–637. doi: 10.1038/nm1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.le Viseur C, Hotfilder M, Bomken S, Wilson K, Röttgers S, Schrauder A, Rosemann A, Irving J, Stam RW, Shultz LD, et al. In childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, blasts at different stages of immunophenotypic maturation have stem cell properties. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mori H, Colman SM, Xiao Z, Ford AM, Healy LE, Donaldson C, Hows JM, Navarrete C, Greaves M. Chromosome translocations and covert leukemic clones are generated during normal fetal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8242–8247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112218799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quijano CA, Moore D, Arthur D, Feusner J, Winter SS, Pallavicini MG. Cytogenetically aberrant cells are present in the CD34+CD33-38-19- marrow compartment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1997;11:1508–1515. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cox CV, Evely RS, Oakhill A, Pamphilon DH, Goulden NJ, Blair A. Characterization of acute lymphoblastic leukemia progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104:2919–2925. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wei J, Wunderlich M, Fox C, Alvarez S, Cigudosa JC, Wilhelm JS, Zheng Y, Cancelas JA, Gu Y, Jansen M, et al. Microenvironment determines lineage fate in a human model of MLL-AF9 leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barabé F, Kennedy JA, Hope KJ, Dick JE. Modeling the initiation and progression of human acute leukemia in mice. Science. 2007;316:600–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1139851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhatia R, Holtz M, Niu N, Gray R, Snyder DS, Sawyers CL, Arber DA, Slovak ML, Forman SJ. Persistence of malignant hematopoietic progenitors in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in complete cytogenetic remission following imatinib mesylate treatment. Blood. 2003;101:4701–4707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Y, Chen Y, Douglas L, Li S. beta-Catenin is essential for survival of leukemic stem cells insensitive to kinase inhibition in mice with BCR-ABL-induced chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:109–116. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Voncken JW, Kaartinen V, Pattengale PK, Germeraad WT, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. BCR/ABL P210 and P190 cause distinct leukemia in transgenic mice. Blood. 1995;86:4603–4611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brain JM, Goodyer N, Laneuville P. Measurement of genomic instability in preleukemic P190BCR/ABL transgenic mice using inter-simple sequence repeat polymerase chain reaction. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4895–4898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jumaa H, Bossaller L, Portugal K, Storch B, Lotz M, Flemming A, Schrappe M, Postila V, Riikonen P, Pelkonen J, et al. Deficiency of the adaptor SLP-65 in pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2003;423:452–456. doi: 10.1038/nature01608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klein F, Feldhahn N, Herzog S, Sprangers M, Mooster JL, Jumaa H, Müschen M. BCR-ABL1 induces aberrant splicing of IKAROS and lineage infidelity in pre-B lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1118–1124. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jumaa H, Mitterer M, Reth M, Nielsen PJ. The absence of SLP65 and Btk blocks B cell development at the preB cell receptor-positive stage. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2164–2169. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2164::aid-immu2164>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iacobucci I, Lonetti A, Messa F, Cilloni D, Arruga F, Ottaviani E, Paolini S, Papayannidis C, Piccaluga PP, Giannoulia P, et al. Expression of spliced oncogenic Ikaros isoforms in Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: implications for a new mechanism of resistance. Blood. 2008;112:3847–3855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams RT, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Arf gene loss enhances oncogenicity and limits imatinib response in mouse models of Bcr-Abl-induced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6688–6693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hu Y, Liu Y, Pelletier S, Buchdunger E, Warmuth M, Fabbro D, Hallek M, Van Etten RA, Li S. Requirement of Src kinases Lyn, Hck and Fgr for BCR-ABL1-induced B-lymphoblastic leukemia but not chronic myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:453–461. doi: 10.1038/ng1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ptasznik A, Nakata Y, Kalota A, Emerson SG, Gewirtz AM. Short interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting the Lyn kinase induces apoptosis in primary, and drug-resistant, BCR-ABL1(+) leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:1187–1189. doi: 10.1038/nm1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schenk TM, Keyhani A, Bottcher S, Kliche KO, Goodacre A, Guo JQ, Arlinghaus RB, Kantarjian HM, Andreeff M. Multilineage involvement of Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1998;12:666–674. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anastasi J, Feng J, Dickstein JI, Le Beau MM, Rubin CM, Larson RA, Rowley JD, Vardiman JW. Lineage involvement by BCR/ABL in Ph+ lymphoblastic leukemias: chronic myelogenous leukemia presenting in lymphoid blast vs Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cobaleda C, Gutiérrez-Cianca N, Pérez-Losada J, Flores T, García-Sanz R, González M, Sánchez-García I. A primitive hematopoietic cell is the target for the leukemic transformation in human philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2000;95:1007–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hotfilder M, Röttgers S, Rosemann A, Schrauder A, Schrappe M, Pieters R, Jürgens H, Harbott J, Vormoor J. Leukemic stem cells in childhood high-risk ALL/t(9; 22) and t(4; 11) are present in primitive lymphoid-restricted CD34+CD19- cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1442–1449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]