Abstract

Granulomatous hypophysitis is a rare pituitary condition that commonly presents with enlargement of the pituitary gland. A 31-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a severe headache and bitemporal hemianopsia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an 18 × 10-mm sellar mass with suprasellar extension and compression of the optic chiasm. Interestingly, brain MRI had shown no abnormal finding 4 months previously. On hormonal examination, hypopituitarism with mild hyperprolactinemia was noted. The biopsy revealed granulomatous changes with multinucleated giant cells. We herein report this rare case and discuss the relevant literature.

Keywords: Granulomatous hypophysitis, Headache, Hypopituitarism

INTRODUCTION

Hypophysitis is an inflammatory condition of the pituitary gland that is often mistaken for other pituitary mass lesions [1]. Granulomatous hypophysitis is a rare inflammatory disorder, accounting for < 1% of cases involving panhypopituitarism or visual field defects with headaches. Granulomatous hypophysitis commonly presents with enlargement of the pituitary gland that mimics an adenoma, making it difficult to confirm the disease until the time of surgery. In Korea, only one case has been previously reported. We herein report a 31-year-old woman who had normal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings 4 months prior to admission and was diagnosed with granulomatous hypophysitis at the time of surgery.

CASE REPORT

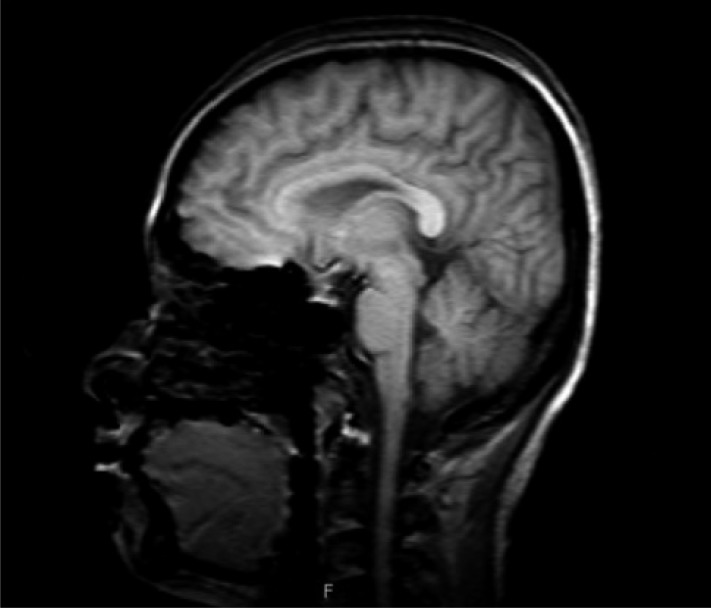

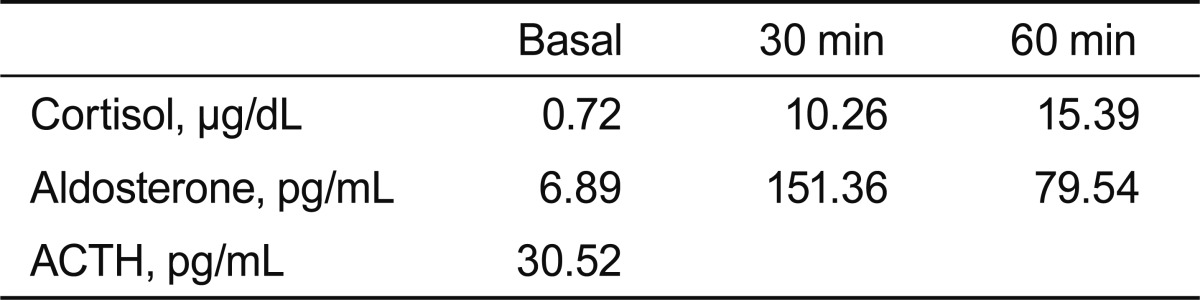

A 31-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with severe headache, nausea, and vomiting. About 6 months previously, she had given birth to her second child. No excessive postpartum bleeding occurred and no blood transfusion was required. Four months before admission to our hospital, she had visited the Department of Neurology due to a bilateral temporal headache. Neurologic examination and brain MRI showed no abnormal finding (Fig. 1), so she was treated pharmacologically with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. However, her condition did not improve. Due to nausea and vomiting for 2 weeks, she was brought to the emergency room. No menstruation or galactorrhea was observed at that time. On physical examination, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate was 58 beat/min, respiratory rate was 16 breath/min, and body temperature was 36.6℃. A neurologic examination revealed bitemporal hemianopsia. Initial complete blood analysis revealed a white blood cell count of 4,860/mm3, a hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL, and a platelet count of 241,000/mm3. The biochemical test results were as follows: protein, 7.2 g/dL; albumin, 4.2 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 16 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 6 IU/L; blood urea nitrogen, 5.9 mg/dL; and creatinine, 0.5 mg/dL. The electrolyte test results were as follows: sodium, 113 mEq/L; potassium, 4.3 mEq/L; and chloride, 82 mEq/L. The blood and urine osmolarities were 249 and 691 mOsm/kg, respectively. The thyroid function test results were as follows: serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, 0.56 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.27 to 4.2); free T4, 0.91 ng/dL (0.93 to 1.7); and T3, 0.89 ng/mL (0.8 to 2.0). We performed a combined pituitary stimulation function test and rapid adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test for further assessment. We injected regular insulin (0.1 µ/kg), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (200 µg), and luteinizing hormone (LH)-releasing hormone (100 µg); 2 hours later, the patient's blood glucose level fell to 60 mg/dL and she complained of hypoglycemic symptoms. The rapid ACTH stimulation test showed no increase in cortisol (Table 1). The combined pituitary function stimulation test showed no increase in serum growth hormone, ACTH, or TSH level. Serum levels of LH and follicle-stimulating hormone were normal over time, and mild hyperprolactinemia was present with normal increments over time (Table 2). T1- and T2-weighted MRI showed an 18 × 10-mm round mass with isosignal intensity in the sella. The lesion extended to the suprasella and slightly compressed the optic chiasm (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Coronal and sagittal magnetic resonance images of the sella showed no abnormal signal intensity 4 months prior to admission.

Table 1.

Results of the rapid adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test

Table 2.

Results of the combined pituitary function testa

a0.1 unit/kg regular insulin, 400 µg thyrotropin-releasing hormone, and 100 µg luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone intravenously.

Figure 2.

T1- and T2-weighted images showing an 18 × 10-mm oval area of isosignal intensity in the sella, with suprasellar extension resulting in slight compression of the optic chiasm. No definitive evidence of adjacent cavernous sinus invasion is visible.

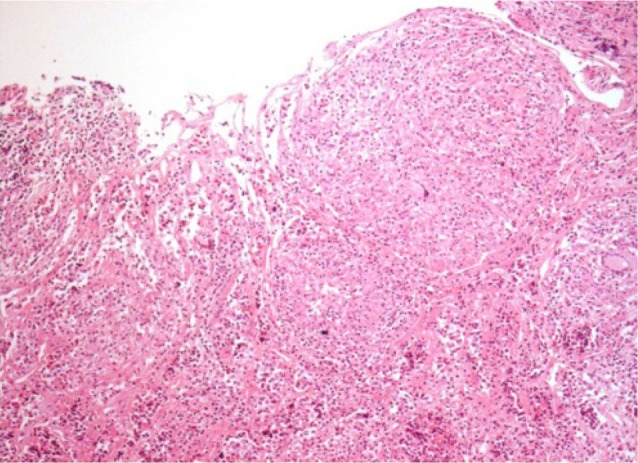

Prednisolone and levothyroxine were prescribed and the mass was removed using a transsphenoidal approach. The pathologic findings revealed granulomatous changes with multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 3). Visual disturbances improved after surgery. The acid-fast bacilli stain, tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction, angiotensinogen-converting enzyme, and venereal disease tests yielded no abnormal finding. The patient was finally diagnosed with idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis, and estradiol and progesterone were added to the prednisolone and levothyroxine for maintenance therapy. She is now under outpatient follow-up care.

Figure 3.

Histologic examination showed lymphocy te infiltration and noncaseous granulomatous changes (H&E, × 100).

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory pituitary lesions are extremely rare and can be classified into three clinicopathologic entities: lymphocytic, xanthomatous, and granulomatous hypophysitis [1]. Granulomatous hypophysitis, a rare chronic inflammation of the pituitary gland that creates granulomas, has been reported in < 1% of sellar lesions based on surgical findings with the transsphenoidal approach [2]. Granulomatous hypophysitis occurs with equal frequency in males and females [3].

Lymphocytic hypophysitis is distinguished from granulomatous hypophysitis by the absence of nodular aggregations of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, but these two diseases show ultrastructural similarities [4]. The two entities may have the same pathogenetic background or even represent different stages of the same disease [5], and some authors have suggested that they represent an autoimmune spectrum from a purely lymphocytic form, constituting the predominant early lesion, to a granulomatous form appearing later [6]. Granulomatous hypophysitis, however, differs from lymphocytic hypophysitis in certain epidemiological features, which are mostly associated with pregnancy and autoimmune diseases [6]. Imaging studies can help to distinguish granulomatous hypophysitis from pituitary adenoma. In patients with granulomatous hypophysitis, MRI usually shows symmetric enlargement of the pituitary gland, pre-contrast homogeneity of the pituitary mass, an intact sellar floor, and rapid enhancement of the pituitary stalk after gadolinium administration [7]. However, these findings are not specific and are quite indistinguishable from other neoplastic or inflammatory hypophyseal processes on imaging [7].

Headaches are the most common presenting symptom of granulomatous hypophysitis. Patients may also present with progressive chiasmal compression, hypopituitarism, amenorrhea-galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, fatigue, diabetes insipidus, a sudden onset of aseptic meningitis, and/or blurred vision. Granulomatous hypophysitis is difficult to differentiate from a simple adenoma on the basis of clinical manifestations or imaging findings. The diagnosis is usually made by histopathologic findings [3,5].

Secondary causes of granulomatous hypophysitis include infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, and fungal), systemic inflammation (sarcoidosis, Wegener's granulomatosis, Crohn's disease, and histiocytosis X), and foreign body reactions (ruptured Rathke's cysts) [2].

Transsphenoidal surgery is a primary diagnostic and therapeutic option [1]. Hypopituitarism resolves after surgery in some cases, but many patients remain on full hormone replacement therapy, as in our case [1,8].

Lymphocytic hypophysitis was first presumed in the present case because of the rapidly growing sellar lesion observed on MRI and the patient's history of delivery 6 months prior to admission. However, the postoperative biopsy revealed granulomatous hypophysitis, and other examinations ruled out secondary causes of hypophysitis.

In summary, idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis is a very rare pituitary condition that is difficult to diagnose preoperatively. The treatment of this disease is surgery, which helps in diagnosis and treatment, and hormone replacement.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

References

- 1.Cheung CC, Ezzat S, Smyth HS, Asa SL. The spectrum and significance of primary hypophysitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1048–1053. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stott V, Manning P, Hung N. Idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis. N Z Med J. 2005;118:U1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasile M, Marsot-Dupuch K, Kujas M, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis: clinical and imaging features. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s002340050357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee CI, Chung YG, Kim SD, Lee HK. Idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2003;34:386–388. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honegger J, Fahlbusch R, Bornemann A, et al. Lymphocytic and granulomatous hypophysitis: experience with nine cases. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:713–722. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caturegli P, Newschaffer C, Olivi A, Pomper MG, Burger PC, Rose NR. Autoimmune hypophysitis. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:599–614. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehndiratta MM, Phul P, Singh AK, Garg S, Bali R. Granulomatous hypophysitis: an interesting and rare cause mimicking pituitary mass. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:653–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brisman MH, Morgello S, Silvers A, Klein I, Post KD. Idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis. Neurosurg Focus. 1996;1:e7. doi: 10.3171/foc.1996.1.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]