Abstract

The Snf2 family represents a functionally diverse class of ATPase sharing the ability to modify DNA structure. Here we use a magnetic trap and an Atomic Force Microscope to monitor the activity of a member of this class: the RSC complex. This enzyme causes transient shortenings in DNA length involving translocation of typically 400 bp within 2 seconds resulting in the formation of a loop whose size depends on both the force applied to the DNA and the ATP concentration. The majority of loops decrease in size within a time similar to that with which they are formed suggesting that the motor has the ability to translocate in different directions. Loop formation is also associated with the generation of negative DNA supercoiling. These observations support the idea that the ATPase motors of the Snf2 family proteins act as DNA translocases specialised to generate transient distortions in DNA structure.

The Snf2 family of proteins possesses distinct helicase motifs, characteristic of the Superfamily II (SFII) group of helicase related proteins. SFII includes bonafide double stranded DNA translocases such as the DNA translocating subunits of type I restriction enzymes (Firman and Szczelkun, 2000), raising the possibility that the helicase motifs within the Snf2 protein family may also function in this way. This hypothesis is supported by recent biochemical characterisation of Snf2 protein action (Havas et al., 2000; Van Komen et al., 2000; Saha et al., 2002; Whitehouse et al., 2003; Fyodorov and Kadonaga, 2002; Jaskelioff et al., 2003).

Many Snf2 proteins have been shown to alter chromatin structure in vitro in an ATP-dependent manner and there is also evidence that some modify the chromatin structure in vivo (reviewed by Becker and Horz, 2002). However, Snf2 proteins are not adapted to function solely on nucleosomes (see for example, Sukhodolets et al., 2001). Instead it appears that a common feature of the Snf2 family is its ability to alter DNA structure and thereby regulate DNA/protein interactions. It remains to be established how the distortion of DNA by Snf2 proteins differs from that carried out by other DNA translocases.

In order to directly monitor the action of a Snf2 protein, we have studied the activity of the RSC chromatin remodelling complex (Cairns et al., 1996) on single DNA molecules using an approach similar to one that has previously proven to be effective in the study of topoisomerases (Strick et al., 2000), DNA helicases (Dessinges et al., 2004) and DNA translocases such as FtsK (Saleh et al., 2004) and RuvAB (Dawid et al., 2004). We find that translocation by the RSC complex is able to generate large loops (hundreds of base pairs long) within which DNA is underwound. The size of these loops was found to depend upon both the tension in DNA and the ATP concentration. Interestingly, the majority of loops were also relaxed in an ATP-dependent reaction which suggests that translocation of the complex is reversible. This ability to reversibly modify the DNA structure could provide a potent means by which Snf2 proteins are able to control a number of protein DNA interactions.

Results

RSC causes transient shortenings in the length of single stretched DNA molecules

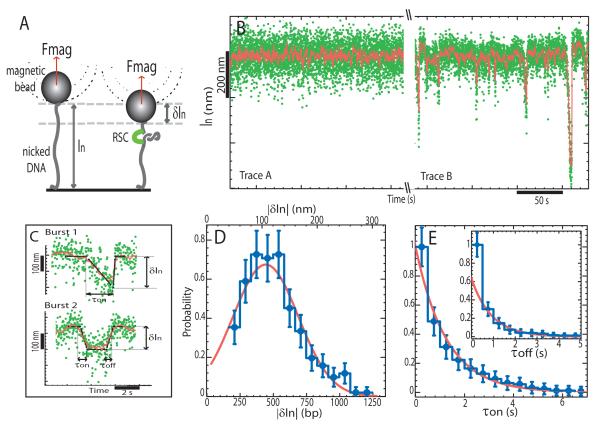

In order to monitor the action of RSC on single DNA molecules, a 3.6 kbp DNA fragment was tethered at one end to a glass slide and at the other to a magnetic bead. Magnets were then used to set the force F stretching the molecule and control the rotation of the bead. Video microscopy was used to monitor the position of the bead and provide a real time measurement of the distance of the bead to the glass surface (schematically illustrated in Fig. 1A). In the absence of RSC, a single nicked DNA molecule undergoes restricted Brownian fluctuations (Fig. 1B, Trace A). In the presence of RSC and ATP, transient reductions in the length δln of the molecule were observed with an on-time τon (Fig. 1B, Trace B and Fig. 1C, bursts 1 and 2). In approximately 50% of cases an apparent stall (or pause) was observed once a maximal change in extension δln was reached and before the molecule reverted to its initial extension (Fig. 1C, burst 2). At 100μM ATP and F = 0.3 pN, an average decrease in extension: < δln >= 106 ± 7 nm (N = 250 events) was measured corresponding to translocation of approximately 420 base pairs. ATP was required for these shortenings to be detected and increasing the ATP concentration led to larger < δln > (see Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Loop extrusion by RSC on a nicked DNA molecule. A) A single DNA is anchored at one end to a glass surface and at the other to a magnetic bead that is pulled by small magnets placed above the sample. We monitor the molecule’s extension ln at a fixed force (F ≈ 0.3pN) and fixed [ATP] = 100 μM. Binding of RSC to DNA decreases its extension by δln. B) Time traces of the variation in DNA’s extension without RSC (Trace A) and in the presence of RSC (Trace B) (non-averaged raw data (green) and averaged over 1 sec.(red)). C) Detail of two different types of events observed with RSC (raw data (green), averaged over 1 sec.(red) and polygonal fit (black) from which we deduce δln, τon and τoff; see Material and Methods for data treatement). Burst 1, a slow decrease of the extension, followed after a short pause by a quick return to the original extension: δln=200 nm, τon=1.96s, τoff=0.13s. Burst 2, a slow decrease of the extension, followed after a stall (or pause) by a slow return to the original length: δln=143nm, τon=0.57s, τoff=0.58s. D) Histogram of the change in extension δln (N = 250 events). A gaussian fit yields: < δln >= −106±7 nm. E) Cumulative probability distributions of τon and τoff for all bursts. The data for the on-times were fitted by: Pon(t > τ) = exp(−τ/τon) with τon = 1.14 ± 0.07s. The on-time data were fitted by: Poff(t > τ)=(1-p) exp(−τ/τoff)+p (τ = 0) with τoff = 0.90±0.13s and p ≈ 40 %; p is the fraction of events with an on-time below the temporal resolution of our set-up (~ 0.5sec).

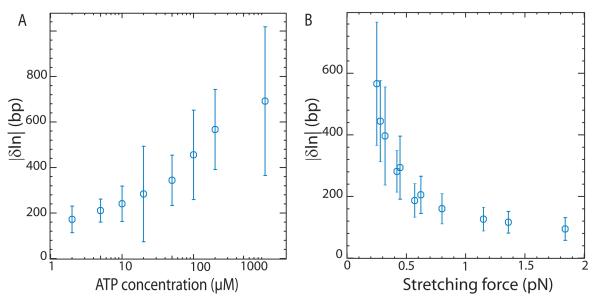

Figure 2.

Dependence of δln A) on ATP concentration at fixed force F = 0.3 pN and B) on stretching force F at fixed [ATP]=100μM. At large forces (F > 1 pN) the decrease in extension δln is overestimated, since we only record the few events with a size clearly larger than the noise level (with standard deviation σn ~ 50 bp). The error bars correspond to the standard deviation of the distribution of δln values.

The probability distribution of δln was found to be gaussian (see Fig. 1D) while the distribution of on-times was exponential (see Fig. 1E). This is in striking contrast with other DNA translocases(Dessinges et al., 2004; Saleh et al., 2004; Dawid et al., 2004) that operate at constant rate v and for which there is a linear relationship between processivity (δln) and on-time: δln = vτon. For these enzymes the probability distributions of δln and τon are similar and exponential.

The shortening events were observed to recover their initial length in two ways. In approximately 40% of cases shortening events reversed to their original extension in a time that was too quick (< 0.5s) to be measured with this set-up, (e.g. Fig. 1C, burst 1). In the remaining 60% of cases the molecule returned to its original length in a time τoff similar to τon (e.g. Fig. 1C, burst 2). Both τon and τoff decreased with increasing ATP concentration; at 10μM ATP: τon = 1.61±0.16 s and τoff = 1.49±0.15 s, while at 200μM ATP: τon = 1.03±0.1 s and τoff = 0.83 ± 0.08 s. This suggests that τon and τoff correlate with translocation by the ATPase motor. Reverse translocation has been reported for other DNA translocases (Dessinges et al., 2004; Saleh et al., 2004; Dawid et al., 2004). In the present case it could occur either as a result of the concerted action of a complex comprising two or more motors or as a result of a reversal in the orientation of translocation by a single motor (as illustrated in Fig. 6).

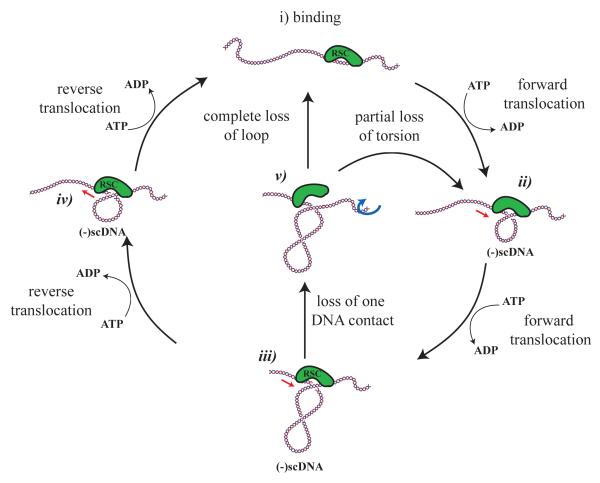

Figure 6.

Model for DNA translocation by RSC. In order to form loops on DNA, the RSC complex must make at least two contacts with DNA. If one of these contacts is capable of DNA translocation, DNA could be drawn into a loop in the presesnce of ATP as shown in i)-iii). Once formed we observe that the majority of loops are removed in an ATP-dependent reaction that could occur as a result of translocation in the reverse orientation iii), iv) and i). In some cases we observe loops colapsing rapidly. This could occur if either the translocase disengages or another contact constraining DNA is lost iii), v), i). In this latter case the translocase would be likely to restart the cycle at a different location on the DNA fragment. Consistent with this we observed ATP dependent redistribution of RSC complexes towards the DNA ends in the AFM images. As we observe differences in the degree of supercoiling under different conditions, it is likely that in some cases torsion could be partially relaxed as a result of slippage, v)-ii), in a manner similar to what has been reported for FtsK(Saleh et al., 2005).

Both the RSC and SWI/SNF complexes contain single copies of their catalytic subunits (Saha et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2003) meaning that if two motors were involved, two complexes would need to associate with the DNA molecule. To reduce the probability of such events, all measurements were made under conditions in which shortenings were infrequent. However, as it was not possible to directly measure the number of RSC complexes acting on a DNA molecule, we decided to investigate the effect of RSC on linear DNA by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), in similar buffer conditions (but at F = 0 pN).

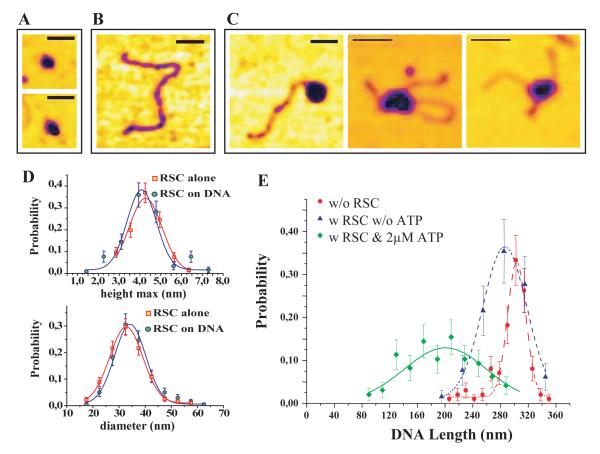

Atomic Force Microscopy shows that single RSC complexes cause ATP dependent reductions in the contour length of DNA

The RSC complex is large enough (it has a mass of approximately 1 MDa) that individual complexes should be observable by AFM. Indeed, imaging of a mica surface onto which RSC complexes had been adsorbed revealed the presence of isolated particles with a diameter of 30nm and a height of 5nm (Fig. 3A,D). When RSC was allowed to bind DNA prior to deposition, AFM imaging revealed the presence of isolated RSC·DNA complexes (Fig. 3C). The size of the RSC particles in these complexes was indistinguishable from free RSC complexes (Fig. 3D) suggesting that single RSC complexes represent the predominant species bound to DNA. In addition to measuring the size of the RSC complex, it was possible to measure the contour length of DNA fragments. In the presence of RSC and 2 μM ATP, the average DNA contour length was shorter by δln = 103 nm (N =97 events) than in their abscence (Fig. 3E). These shortenings were largely ATP-dependent, as the DNA shortening observed in the presence of RSC only was 17 nm. The position of the RSC complex along DNA was also affected by the presence of ATP. Without ATP about 6% of RSC complexes (4 out of 65 events) were observed at the DNA’s extremities. This is slightly lower than than the ~ 20% expected for a random binding of RSC along DNA. However, in the presence of 2μM ATP 64% of the observed complexes (62 out of 97 events) are localised at the molecule’s ends, see Fig. 3C(left). For the 36% of complexes located away from the extremities, relaxed or supercoiled loops associated with the complex could sometimes be identified, see Fig. 3C(middle and right). The fact that the position of RSC along DNA is significantly altered in the presence of ATP suggests that the majority of RSC complexes translocate to the molecule’s ends from which they dissociate relatively slowly. In combination these observations suggest that translocation of RSC along DNA is accompanied by loop formation.

Figure 3.

AFM images of RSC complex on linear DNA molecules. A) Images of isolated RSC complexes on a mica surface. B) Image of a 891 bp linear DNA molecule. C) Images of RSC·DNA complexes (in presence of 2μM ATP) located either at the DNA’s end or at a mid-position. In the latter two cases notice the presence of a (relaxed or supercoiled) loop associated with the complex - (bar=50nm). D) Histograms of the maximal height (h) and diameter (D) for isolated and DNA bound RSC complexes at 2μM ATP. The similarity of the histograms indicates that in the conditions of our experiments RSC binds to DNA as a single complex. E) Distribution of the DNA contour length l; without RSC: l = 303 ± 2 nm; with RSC but without ATP: l = 286 ± 5 nm; with RSC and 2μM ATP: l = 200 ± 8 nm.

The finding that single RSC complexes generate ATP dependent reductions in the contour length of DNA similar to the shortenings observed with the magnetic trap set-up provides good evidence that in both cases single complexes are responsible for the change in the DNA’s extension. This supports the model illustrated in Fig. 6 in which RSC translocates along the molecule while forming a loop of DNA whose size may be reduced either by dissociation of the complex or as a result of a reversal of its translocation direction.

DNA shortening by RSC is sensitive to the tension in DNA

Although the extent of DNA shortening observed in the AFM images and measured with the magnetic trap set-up were comparable, they were not identical. One difference between the two approaches is that in the AFM assay the RSC complex associates with an unstressed linear DNA, while in the magnetic trap experiment the DNA is maintained under a small amount of tension (a fraction of pN, comparable to the tension existing in naturally supercoiled DNA (Charvin et al., 2004)).

To investigate how the force applied to DNA affected the action of RSC, the extent of DNA shortening was measured for different forces (at fixed [ATP]=100 μM). The results show that the average size of shortening events decreased as the tension increased, see Fig. 2B. The largest average change in extension < δln >= 130 ± 7 nm (N =59 events) was observed at the lowest force investigated (F =0.25 pN). It then decreased with increasing force, with no DNA distortions being detected at forces larger than about 3 pN. The finding that force has such a strong effect on the average size of the DNA shortening events suggests that the tension the motor is working against may play a role in limiting the extent of translocation.

The DNA loop generated by RSC is subject to negative superhelical torsion

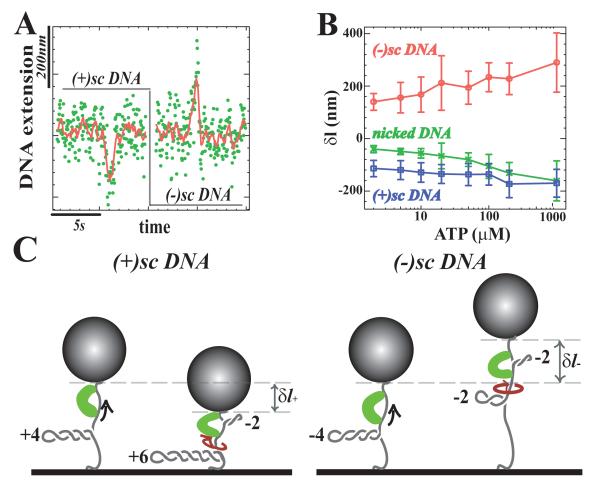

An attractive feature of the magnetic trap is that by rotating the magnetic bead positive or negative turns can be introduced onto an unicked DNA molecule. Such a supercoiled (sc)DNA may form plectonemes of either positive or negative chirality whith significant reduction in the extension of the molecule. For example, at a force F =0.3 pN the introduction of one superhelical turn results in a shortening of lp = 60 nm (Charvin et al., 2004). The data presented in Figs.1 and 2 were obtained using nicked or relaxed molecules where DNA torsion does not contribute significantly to the observed shortening events. By comparing these data to measurements made on (+) or (−)scDNA it is possible to investigate whether the DNA shortenings induced by RSC are associated with the induction of local torsion in the molecule. Fig. 4A and B show that on (+)scDNA (at [ATP]=100 μM) the action of RSC results in a variation of δl+ = −138 ± 6 nm (N = 492 events) slightly smaller than the shortening δln = −106 nm observed on nicked DNA (see Fig. 1D). In contrast, on (−)scDNA a lengthening of δl− = +259±4 nm (N = 221 events) is observed. This increase in extension is most likely due to a reduction in the size of the plectonemes on (−)scDNA (schematically illustrated in Fig. 4C), suggesting that negative torsion is generated in the DNA loop formed by the action of the RSC complex.

Figure 4.

Transient DNA topology changes associated with RSC translocation. A) Time traces on (+) and (−)scDNA, in presence of 100μM ATP at F = 0.3pN (raw data: (green) and averaged over 1 sec.(red)). B) Dependence of δl on ATP concentration for nicked, (−)scDNA and (+)scDNA (the error bars correspond to the standard deviation of the l distribution). C) Sketch showing the effect of twisting during RSC translocation on (+) and (−)scDNA. On (+)scDNA the generation of a loop negatively twisted by 2 turns is compensated by the addition of 2 positive supercoils on the remaining DNA, thus reducing the distance of the bead to the surface. On (−)scDNA the generation of a negatively supercoiled loop reduces of the number of (−) supercoils in the rest of the molecule and increases in the overall DNA’s extension.

If the action of RSC results in the formation of a loop of size lt− that contains n− negative supercoils, an identical number of compensatory positive supercoils must be formed outside the loop which would reduce the number of plectonemes on (−)scDNA, causing an increase in the molecule’s extension by n−lp, see Fig. 4C(right). The overall change in the DNA’s extension is then: δl− = lt− + n−lp = 259 nm. Assuming that the average extent of DNA translocated by RSC on (−)scDNA is the same as on a nicked molecule, lt− = δln = −106 nm, we deduce that n− = 6.1 turns. This would indicate that (at [ATP] =100 μM and F =0.3 pN) the RSC complex caused the generation of a loop containing approximately 420 bp of DNA with 6.1 negative superhelical turns, corresponding to a degree of supercoiling σ = −0.15. However this should be viewed as an upper bound on |σ|, see discussion.

In a similar manner, we can estimate the number of compensatory turns introduced on (+)scDNA, n+ considering that the overall change in the DNA’s extension is: δl+ = lt+ − n+lp, see Fig. 4C(left). Making the same hypothesis as for (−)scDNA, i.e. lt+ = δln = −106 nm, we deduce that n+ = 0.6 turns are introduced during translocation of RSC on (+)scDNA. These different results for (+) and (−)scDNA (n+ ≠ n−) indicate that the extent of negative torsion introduced in the DNA loop associated with RSC is affected by the overall torsion (positive or negative) in the remaining portion of the molecule.

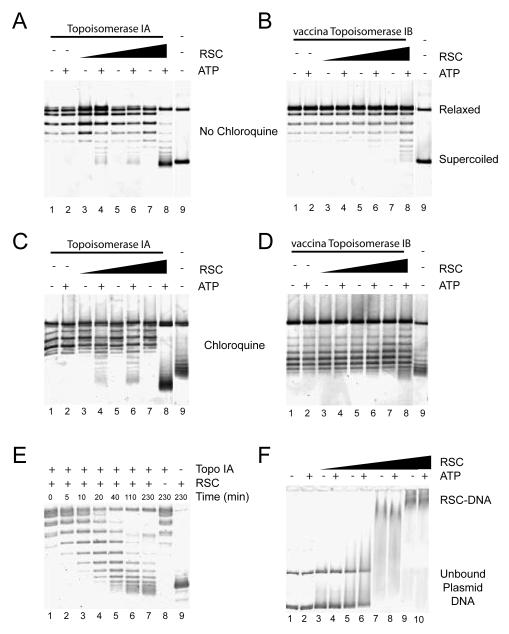

RSC could generate loops of DNA containing negative supercoils either in the form of unconstrained supercoils, or in the form of constrained supercoils formed by wrapping the molecule around the RSC complex. The latter has to be given serious consideration given that DNA protruding from RSC complexes can only be seen in some of our AFM images and that another Snf2 protein has been proposed to wrap DNA (Beerens et al., 2005). In order to distinguish between these possibilities we analysed the effect of RSC on DNA topology in bulk assays. In the presence of E.coli Topoisomerase 1A (Topo1A), which preferentially removes (−) supercoils, RSC caused an ATP-dependent increase in the linking number of plasmid DNA which could be detected as faster migrating bands following agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5A). The high mobility of these topoisomers in the presence of chloroquine indicates that (+)scDNA is generated in the presence of RSC, ATP and Topo1A (see Fig. 5C lane 8). The level of positive supercoiling increases in the presence of increasing amounts of RSC complex and when RSC and Topo1A are incubated for longer times indicating that alterations to topology accumulate in the presence of RSC and ATP (Fig. 5C and E). These changes to DNA topology are unlikely to require DNA molecules to be coated with many RSC complexes as they are detectable under conditions in which few RSC complexes interact with plasmid DNA, as shown by native gel shift assays (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

Detection of unconstrained superhelical torsion in the presence of RSC. Relaxed pUC18 DNA (40ng) was incubated in the presence of recombinant E.coli Topoisomerase Ia (A, C, E) or recombinant vaccina Topoisomerase Ib (B, D), RSC and ATP as indicated for 1 hour at 30° C. RSC was present at 10nM (lanes 3 and 4), 33nM (lanes 5 and 6), 100nM (lanes 7 and 8), 300 nM (F lanes 9 and 10). Following incubation, proteins were removed and topoisomers resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was performed in the absence of chloroquine (A, B, E, F) or in the presence of 1μg/ml chloroquine (C, D). In the presence of RSC and ATP faster migrating supercoiled DNA was detected in the presence of Topoisomerase IA which selectively removes negative supercoils. The mobility of this DNA was increased rather than reduced in the presence of chloroquine indicating that this DNA is positively supercoiled (C). Little change in DNA topology was detected following incubation with RSC and vaccina Topoisomerase Ib indicating that RSC is not stably wrapped by the complex. In F, reactions were performed in the absence of topoisomerases and loaded directly onto 0.3× TBE agarose gel. This shows that the changes in topology detected in Figs. A and C were obtained under conditions in which DNA is partially bound by RSC.

If RSC was wrapping DNA rather than forming the negatively supercoiled and freely accessible DNA loop suggested by the experiments with Topo1A, one would expect negatively supercoiled topoisomers to accumulate in the presence of vaccinia Topoisomerase 1B (which relaxes both (+) and (−)supercoils). Instead only a small proportion of both (+) and (−) supercoiled topoisomers are generated at high RSC concentrations (Fig. 5B and D).

Combining these results with the single molecule measurements and AFM images, we conclude that the RSC complex generates loops of negatively supercoiled DNA, accessible to topoisomerases and similar in size to the circumference of the RSC complex.

Discussion

Using a single molecule magnetic trap set-up, we found that RSC causes transient reductions in the DNA’s extension. AFM imaging of surface adsorbed RSC·DNA complexes reveals that similar shortenings in the form of relaxed or supercoiled loops are generated by single complexes. We therefore propose that RSC actively and reversibly translocates DNA, the size of the translocated loop being ATP and tension dependent, see Fig. 2. We also find that the translocated DNA becomes underwound during the course of loop formation, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Although all the data (single molecule and bulk) indicate that negatively underwound DNA accumulates within the loops, there is a difference in the extent of this effect on (−) and (+)scDNA. There are a number of possible explanations for this observation. One possibility is that the size of the DNA loop lt± differs on (±)scDNA templates. Supporting this, on (−)scDNA the total change in extension observed δl− is in the same direction as the applied force whereas on (+)scDNA the contraction works against the DNA tension. The measurements on nicked DNA molecules at different forces indicate that the loop size |δln| decreases with increasing work against the force (Fig. 2). This would imply that lt− ≤ δln ≤ lt+ < 0. Another explanation is that the number of negative supercoils generated in the translocated loop n± differs on (±)scDNA. This could be due to variation in the step size on (+) and (−)scDNA or to differences in the amount of slippage that occurs during translocation. differences in slippage on (±)scDNA have been reported for an other translocase: FtsK (Saleh et al., 2005). Increased slippage at high ATP concentrations could also explain why the calculated superhelical density generated by RSC decreases with ATP concentration (Supplementary Figure 1).

Although we cannot calculate whether n±, lt± or a combination of both are altered on (±)scDNA we can obtain useful bounds. For example the degree of supercoiling in the loop formed by RSC on (−)scDNA (at 100 μM ATP and F = 0.3 pN) is bounded from above by:

Here h = 3.6nm is the DNA pitch and ζ is the molecule’s relative extension derived from the WLC model (see supplementary Fig. 3) which allows us to estimate the contour length of the extruded loop. Since δl− > 0, |σ−| is also bounded from below: |σ−| > ζh/lp = 0.04. These bounds imply that RSC generates much less than one turn per every 10.5 bps of (−)scDNA translocated, but probably enough torsion in the loop to induce its partial melting (which occurs when σ− < −0.06).

A means by which RSC might generate negative superhelical loops involves rotation associated with translocation along the helical DNA backbone. Similar effects have been observed with other DNA translocases (?Seidel et al., 2004). If translocation proceeded by maintaining contact with each base along the DNA backbone, then one negative rotation would be generated for every 10.5 bp translocated (Seidel et al., 2004). In contrast our observations indicate that the amount of negative rotation (σ−) generated is between −0.15 and −0.04 rotations per 10.5 bp translocated. This can be explained if the motion of RSC along DNA is broken down into steps of about 12 bps (or multiples thereof), slightly greater than the helical repeat (Saleh et al., 2005). This could be an important adaptation for a translocase such as RSC that may be specialised in engaging DNA wrapped around the histone octamer.

Another distinctive feature of RSC is that while the length of the translocated loop δln is gaussianly distributed (Fig. 1D), the time taken to form the loop τon is exponentially distributed (Fig. 1E). This different statistical behaviour can be explained if tensional or torsional load during translocation slows down the activity of the complex and determines the change in DNA extension. This explanation accounts for the observation in many cases of a stall phase (Fig. 1C, burst 2) and for the possibility of distinct torsion-induced slippage on (+) or (−)scDNA, accounting for the previously mentioned observation that n+ ≠ n−. When the motor is working against relatively high opposing forces (or torques) there may be an increased likelihood that the translocase:

slips (i.e. let the DNA in the loop swivel and relax part of the torsion),

engages with the opposite strand resulting in a gradual reduction in the molecule’s extension (see Fig. 6) or

dissociates from DNA resulting in a rapid extension in DNA length.

A thermal ratchet model of the translocation of RSC (that will be presented elsewhere) reproduces all the features reported here. It assumes that the RSC·DNA complex proceeds upon ATP binding into a productive translocation mode with a rate that is slowed down as the energy stored in the loop increases. Translocation is thus slowed down (and eventually stalled) as more DNA is being pulled into the RSC associated DNA loop. The different distributions of δln and τon are recovered as well as their dependence on force and ATP concentration.

The ability to generate both loops and torsion in DNA provides the RSC complex with potent means by which it could drive DNA over the surface of nucleosomes using variants of the twist defect diffusion and bulge diffusion mechanisms that have been proposed by many research groups (for a review see Flaus and Owen-Hughes, 2003). The reversibility with which the RSC complex acts is especially interesting in this respect as it would provide a means by which distortions could be generated that might assist the traversing of an energetically unfavourable intermediate conformation. The subsequent reversal in orientation would enable DNA to be returned to its original state perhaps restoring a more canonical nucleosome structure at a different location along a DNA fragment. Given that the shortening of DNA by RSC is sensitive to the tension and torsion in the molecule, we would anticipate that the size of distortions within a nucleosomal context may well differ from what we have observed here. While it will be fascinating to learn how different the action of the RSC complex is when it functions in a nucleosomal context, this may be technically difficult. It will for example, be hard to guarantee that possible distortions of chromatin fragments result from the action of RSC complexes engaged with DNA on the surface of nuclesomes rather than on DNA adjacent to or between them. The observations we have made with RSC are likely to apply to other SWI/SNF related complexes as we have observed that recombinant BRG1 and Brm proteins, the catalytic subunits of human forms of the SWI/SNF complex cause similar alterations to DNA (Supplementary Fig. 2).

While in many cases the function of SWI/SNF complexes is closely tied to nucleosome remodelling, the possibility that they may have additional functions involving translocation along longer lengths of DNA should not be discounted. For example, the generation of non-B form DNA structures by SWI/SNF complexes may not require the presence of nucleosomes (Liu et al., 2001). Images have been obtained of SWI/SNF in association with a loop that contains several nucleosomes (Bazett-Jones et al., 1999). Some aspects of the pathway by which RSC distorts DNA are likely to be shared with other Snf2 family proteins. Of special interest in this respect is the ability of the RSC complex to reverse its translocation orientation with high probability. This potentially provides Snf2 motor proteins with multiple opportunities to reconfigure protein/DNA interactions in comparison to more processive translocases that might tend to stall on collision with a stable barrier. It will be interesting to investigate what features of RSC action are shared with other classes of Snf2-related proteins.

Material and Methods

Sample preparation and magnetic trap experimental setup

A linear DNA fragment (≈ 3.6 kbp) was obtained with KpnI and SacI restrictions of plasmid pSA580 (gift of Sankar Adhya). Two “tails” were synthesized with biotin or digoxigenin-labeled nucleotides by PCR of the multiple cloning site of a pBS plasmid comprising the restriction sites for KpnI and SacI. Following restriction of these labelled “tails”, they were ligated to the complementary ends of the linear fragment. These DNA molecules were then attached at one end to the glass surface of a microscope flow-chamber (previously coated with anti-digoxigenin) and at the other end to a 1μm paramagnetic bead (DYNAL MyOne beads coated with streptavidin). Small magnets (Strick et al., 1998) were used to twist and pull on single DNA molecules attached to the beads. The DNA’s extension was monitored by video microscopy of the tethered bead (Gosse and Croquette, 2002). By tracking its 3D position (Gosse and Croquette, 2002; Strick et al., 1996), the extension l =< z > of the molecule can be measured, with an error of ≈ 10nm with 1 second averaging. The horizontal motion of the bead < δx2 > allows for the determination of the stretching force via the equipartition theorem: F = kBTl/ < δx2 >. F was measured with 10% accuracy. To eliminate microscope drift, differential tracking was performed via a second bead glued to the surface. All experiments were performed in the reaction buffer (RB): 50mM KCl, 10mM HEP ES (pH 7.8), 3mM MgCl2, 0.1mM DTT and 60μMBSA. RSC, BRG1 and Brm were purified as previously described (Saha et al., 2002; Phelan et al., 1999).

Data Processing

The determination of the change in extension of a DNA molecule δln due to its interaction with RSC as well as the measurement of τon and τoff requires the recording and processing of the elongation versus time signal l(t). Each burst of activity is fitted to a polygon defined by its 6 vertices: li, ti (i=1,…,6), see Fig. 1C. Of the polygon’s five segments, three are set to be horizontal ones (segments 1,3 and 5) and we further require: l1 = l2 = l5 = l6. Segments 1 and 3 are followed by a shortening (or lengthening) event (segments 2 and 4). The coordinates of the polygon vertices were adjusted to minimize the fitting error (χ2 test) (Maier et al., 2000). The decrease in extension is: δln=l3 - l2 = l4 - l5; the on-time: τon = t3 - t2 and the on-time: τoff = t5 - t4. The change in extension δln can be given in base pairs using the formula: δln(bp) = N0δln(nm)/ln(F) where ln(F) is the extension at force F of a DNA molecule of N0 bps (measured or computed from the Worm like Chain model (Strick et al., 2003)).

AFM

A 891 bp linear DNA was synthesized by PCR amplification of a segment of the plasmid pOid-O1 (gift of Sankar Adhya). It was purified with a Qiagen PCR purification kit. About 100ng of this DNA was incubated for 8 minutes with equimolar amount of RSC complex in RB (without BSA and with or without ATP). Following incubation, 10–20μl were deposited at room temperature for 2 – 3 minutes on freshly cleaved mica (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, California) coated with poly-L-ornitine (MW 49,000 Sigma St. Louis, MO). The mica was then gently washed with 1 ml of ddH2O (Sigma) and subsequently dried with nitrogen. The sample was imaged in air with a NanoScope III (Digital Instruments) atomic force microscope operating in tapping mode. The AFM images were analysed with the Open source program ImageJ to determine the DNA countour length and RSC diameter and with the program WSxM (Nanotech, Inc.) to determine the height of the complex.

Topoisomerase assays

Assays were performed in 40μl of 10mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 50mM KCl, and 3mM MgCl2. Where indicated Mg:ATP was present at 1mM. Reactions contained 40ng relaxed pUC18 DNA, topoisomerase and RSC as indicated. One unit of recombinant vaccina topoisomerase Ib or E.coli topoisomerase Ia were included in reactions as indicated (1 unit defined as the amount of enzyme required to relax 20ng supercoiled pUC18 DNA in 2 minutes under the reaction conditions described above). Reactions were terminated by addition of 10μl 50mM Tris (pH 7.5), 3% SDS, 100mM EDTA, 100μg/ml Proteinase K and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Products were resolved by electrophoresis on 1% Agarose TBE gels with or without chloroquine (1μg/ml) as indicated. DNA was detected using a scanning fluorimeter following staining with Sybr gold (Molecular Probes). For gel shift analysis reactions performed in the absence of topoisomerase were loaded directly onto 0.3×TBE 1% agarose gels at 4° C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank A.Shankar for providing some of the plasmids used in these experiments, C.Bustamante for communicating to us results of a similar and complementary study on the action of RSC on stretched reconstituted chromatin and K.C.Neuman, O.A.Saleh, J.F. Allemand and L.Finzi for fruitful discussions. G.L. was funded by grants from the French Ministry of Foreign A airs and the ARC. D.D. acknowledges support from the Italian Ministry of Instruction, Universities and Research. H.F., C.S. and T.O-H. acknowledge support from the Wellcome Trust. Finally, D.B and V.C. acknowledge support from the CNRS, the ARC and the EU (MolSwitch grant).

References

- Bazett-Jones D, Cote J, Landel C, Peterson C, Workman J. The SWI/SNF complex creates loop domains in DNA and polynucleosome arrays and can disrupt DNA-histone contacts within these domains. Mol.Cell.Biol. 1999;19:1470–1478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker P, Horz W. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu.Rev.Biochem. 2002;71:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerens N, Hoeijmakers J, Kanaar R, Vermeulen W, Wyman C. The CSB protein actively wraps DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:4722–4729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns B, Lorch Y, Li Y, Zhang M, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Du J, Laurent B, Kornberg R. RSC, an essential, abundant chomatin-remodeling complex. Cell. 1996;87:1249–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvin G, Allemand J, Strick T, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Twisting DNA: single molecule studies. Contemp. Phys. 2004;45:383–403. [Google Scholar]

- Dawid A, Croquette V, Grigoriev M, Heslot F. Single-molecule study of RuvAB-mediated Holliday-junction migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(32):11611–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404369101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessinges M, Lionnet T, Xi X, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Single-molecule assay reveals strand switching and enhanced processivity of UvrD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6439–6444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306713101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firman K, Szczelkun M. Measuring motion on DNA by the type I restriction endonuclease EcoR124I using triplex displacement. EMBO J. 2000;19:2094–2102. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Mechanisms for nucleosome mobilization. Biopolymers. 2003;68:563–578. doi: 10.1002/bip.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov D, Kadonaga J. Dynamics of ATP-dependent chromatin assembly by ACF. Nature. 2002;418:897–900. doi: 10.1038/nature00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse C, Croquette V. Magnetic tweezers: micromanipulation and force measurement at the molecular level. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3314–3329. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75672-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havas K, Flaus A, Phelan M, Kingston R, Wade P, Lilley D, Owen-Hughes T. Generation of superhelical torsion by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling activities. Cell. 2000;103:1133–1142. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskelioff M, Van Komen S, Krebs J, Sung P, Peterson C. Rad54p is a chromatin remodeling enzyme required for heteroduplex DNA joint formation with chromatin. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:9212–9218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Liu H, Chen X, Kirby M, Brown P, Zhao K. Regulation of CSF1 promoter by the SWI/SNF-like BAF complex. Cell. 2001;106:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier B, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Replication by a single DNA polymerase of a stretched single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97(22):12002–12007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M, Sif S, Narlikar G, Kingston R. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wittmeyer J, Cairns B. Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2120–2134. doi: 10.1101/gad.995002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh O, Bigot S, Barre F, Allemand J. Analysis of DNA supercoil induction by FtsK indicates translocation without groove-tracking. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nsmb926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh O, Perals C, Barre F, Allemand J. Fast, DNA-sequence independent translocation by FtsK in a single-molecule experiment. EMBO J. 2004;23:2430–2439. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel R, van Noort J, van der Scheer C, Bloom J, Dekker N, Dutta C, Blundell A, Robinson T, Firman K, Dekker C. Real-time observation of DNA translocation by the type I restriction modification enzyme EcoR124I. Nat. Struc. Biol. 2004;11:838–843. doi: 10.1038/nsmb816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Horowitz-Scherer R, Flanagan J, Woodcock C, Peterson C. Structural analysis of yeast SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Nat. Struc. Biol. 2003;10:141–145. doi: 10.1038/nsb888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick T, Allemand J, Bensimon D, Bensimon A, Croquette V. The elasticity of a single supercoiled DNA molecule. Science. 1996;271:1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick T, Allemand J, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Behavior of supercoiled DNA. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2016–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77908-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick T, Croquette V, Bensimon D. Single-molecule analysis of DNA uncoiling by a type II topoisomerase. Nature. 2000;404:901–904. doi: 10.1038/35009144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick T, Desssinges M, Charvin G, Dekker N, Allemand J, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Stretching of macromolecules and proteins. Reports on Progress in Physics. 2003;66:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolets M, Cabrera J, Zhi H, Jin D. RapA, a bacterial homolog of SWI2/SNF2, stimulates RNA polymerase recycling in transcription. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3330–3341. doi: 10.1101/gad.936701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Komen S, Petukhova G, Sigurdsson S, Stratton S, Sung P. Superhelicity-driven homologous DNA pairing by yeast recombination factors Rad51 and Rad54. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse I, Stockdale C, Flaus A, Szczelkun M, Owen-Hughes T. Evidence for DNA translocation by the ISWI chromatin-remodeling enzyme. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(6):1935–1945. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.1935-1945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.