Abstract

Objectives:

Several lines of evidence indicate that sleep plays a critical role in learning and memory. The aim of this study was to evaluate anesthesia resistant memory following sleep deprivation in Drosophila.

Design:

Four to 16 h after aversive olfactory training, flies were sleep deprived for 4 h. Memory was assessed 24 h after training. Training, sleep deprivation, and memory tests were performed at different times during the day to evaluate the importance of the time of day for memory formation. The role of circadian rhythms was further evaluated using circadian clock mutants.

Results

Memory was disrupted when flies were exposed to 4 h of sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase. Interestingly, normal memory was observed following sleep deprivation when the memory test was performed during the 2 h preceding lights-off, a period characterized by maximum wake in flies. We also show that anesthesia resistant memory was less sensitive to sleep deprivation in flies with disrupted circadian rhythms.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that anesthesia resistant memory, a consolidated memory less costly than long-term memory, is sensitive to sleep deprivation. In addition, we provide evidence that circadian factors influence memory vulnerability to sleep deprivation and memory retrieval. Taken together, the data show that memories weakened by sleep deprivation can be retrieved if the animals are tested at the optimal circadian time.

Citation:

Le Glou E; Seugnet L; Shaw PJ; Preat T; Goguel V. Circadian modulation of consolidated memory retrieval following sleep deprivation in Drosophila. SLEEP 2012;35(10):1377-1384.

Keywords: Sleep deprivation, memory retrieval, memory consolidation, circadian rhythms, activity peak, Drosophila, recall, clock mutant

INTRODUCTION

The impact of sleep loss on memory processing is a well-documented phenomenon in human and mammalian models, indicating that sleep plays a critical role both in learning and in consolidation of newly acquired memories. In particular, sleep loss differentially affects various types of memories.1 Studies in mice have examined the effect of 5 h of sleep deprivation following training in a fear-conditioning paradigm, and have shown that sleep deprivation selectively impairs memory consolidation for contextual fear but not cued fear.2,3 This demonstrates that sleep deprivation has a negative effect on memory consolidation, particularly when this process involves the hippocampus. Similar findings have been reported using spatial and non-spatial versions of the Morris water maze, showing that sleep deprivation selectively affects consolidation of hippocampus-dependent spatial memory.4–6 However, despite this knowledge, we still do not understand the role of sleep during memory consolidation. Elucidating the links between sleep, memory consolidation, and neuronal processes necessitates an experimental system where ideally all those elements can be manipulated. Drosophila fulfills these conditions.

The Drosophila central nervous system is composed of neurons and glia that operate on the same fundamental principles as their mammalian counterparts. Even though the Drosophila brain contains only about 100,000 neurons,7 it is highly structured and sustains complex behaviors. Flies have been widely used for the analysis of circadian rhythms,8 the understanding of sleep mechanisms,9 and also to investigate the basis of learning and memory.10 Moreover, Drosophila studies can identify physiological processes that may eventually be generalized to other species, given the conserved repertoire of neuronal proteins between Drosophila and mammals.11

Several paradigms have been developed to study learning and memory in Drosophila, such as courtship conditioning and olfactory appetitive or aversive conditioning. With the associative aversive olfactory protocol, two distinct types of consolidated memories can be formed following several training sessions. Anesthesia resistant memory (ARM) is generally assessed using a reinforced protocol comprising several consecutive training cycles, whereas long-term memory (LTM) is exclusively formed after several cycles each separated by a rest interval. ARM is resistant to cold anesthesia,12 and both ARM and LTM last for days. Importantly, unlike ARM, LTM formation depends on de novo protein synthesis since it is sensitive to a treatment by cycloheximide, an inhibitor of cytoplasmic protein synthesis.12 Another study has confirmed that unlike ARM, LTM is an energetically costly process13 that is thought to require synaptic structural plasticity.14 Neural pathways underlying memory processing in flies are well identified: information is conveyed and integrated in the mushroom bodies (MBs), a symmetrical structure comprised of roughly 2,000 neurons on each side of the brain. Olfactory memories are believed to be stored in the output synapses of the MBs.15,16 Interestingly, key molecular pathways involved in memory processes such as the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway, are conserved from flies to mammals.17–19

Sleep in Drosophila exhibits many key similarities with mammalian sleep.20 Drosophila sleep is characterized by periods of immobility (≥ 5 min) associated with an increase in arousal threshold,21,22 changes in brain electrical activity,23 homeostatic regulation after sleep deprivation,21,22 and changes in gene expression.24,25 Interestingly, several genes that affect sleep are involved in synaptic plasticity and show preferential expression in the MBs.9 In addition, altering MBs neuronal activity modifies sleep, indicating that MBs constitute an important center for sleep regulation as well as for memory processing/storage.26,27

Several studies have provided evidence that learning and memory are sensitive to sleep deprivation in flies. It has been shown that 6 and 12 h of sleep deprivation disrupts learning, as evaluated with an aversive phototaxic suppression protocol, showing extensive homology in sleep deprivation-induced learning impairment between flies and mammals.28 Flies with mutations reducing sleep also show short-term memory (STM) defect in another operant paradigm, heat box conditioning.29 Li et al.30 reported that submitting flies to 24 h of sleep deprivation before conditioning is deleterious for short-term (1 h) olfactory aversive memory formation. Moreover, 4 h sleep deprivation applied anytime from 0 to 8 h after the end of the conditioning leads to a 48-h courtship LTM defect,31 indicating that sleep is necessary for memory consolidation. More recently, it has been shown that the induction of sleep can facilitate the formation of LTM.32 Altogether, these studies demonstrate sleep requirement for learning, STM, and LTM consolidation.

Because ARM is believed to be a less energetically costly process than LTM, it could be expected to exhibit sleep requirement distinct from that required during LTM formation. The present study addresses this question and demonstrates that 4 h of sleep deprivation during aversive olfactory memory consolidation severely impacts ARM. The data show that memory is noticeably affected at the level of the retrieval step, as the detrimental effect of sleep deprivation can be compensated when memory retrieval takes place during a fly waking peak that naturally occurs around day/night transitions. In addition, our data show that memory becomes insensitive to 4 h of sleep deprivation when circadian rhythms are disrupted, indicating that the circadian clock modulates the influence of sleep on consolidated memory.

METHODS

Fly Stocks

Drosophila melanogaster wild-type strain Canton-Special was raised at 18°C with 60% humidity in a 12 h:12 h light-dark (LD) cycle (Lights-on at zeitgeber time 0 [ZT0] = 08:00) on a standard food containing yeast, cornmeal and agar. perS and per0 mutant flies33 were obtained from F. Rouyer (INAF, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Light was provided by standard white fluorescent low-energy bulbs. Light intensity at flies' level was around 250 lux.

Olfactory Conditioning and Behavioral Analysis

One- to 2-day-old flies were transferred in new vials 3-4 days prior to training. For aversive training, flies were conditioned by an odor paired with electric shocks and subsequent exposure to a second odor in the absence of shock, as previously described.34 For massed training, flies received 5 training cycles delivered one right after the other, while for spaced training, flies received 5 training cycles with 15-min rest intervals. Conditioning was performed with groups of 40-50 flies using 3-octanol (> 95% purity; Fluka 74878, Sigma-Aldrich) and 4-methylcyclohexanol (99% purity; Fluka 66360, Sigma-Aldrich) at 0.360 mM and 0.325 mM, respectively. Odors were diluted in paraffin oil (VWR International, Sigma-Aldrich). Conditioning and testing were performed at 25°C with 80% humidity. Otherwise, flies were kept at 18°C with 60% humidity. After conditioning, female flies were individually placed, without CO2 anesthesia, into 65-mm glass tubes (5-mm diameter) containing food, and sleep was evaluated using the Trikinetics activity monitoring system (www.trikinetics.com).22 Two h before the memory test, flies were transferred to vials with food in groups of 16 flies. Memory tests were performed with a T-maze apparatus as previously described.35 Flies could choose for 1 min between 2 arms, each delivering a distinct odor. An index was calculated as the difference between the numbers of flies in each arm divided by the sum of flies in both arms. The performance index (PI) results from the average of 2 reciprocal experiments, so that a 50:50 distribution (no memory) yields a PI of zero. For light-light (LL) analyses, flies were raised in LD condition and placed in LL from emergence until the end of the experiment. In parallel to each experiment, wild-type flies in regular bottles were conditioned and used as internal controls (data not shown). Each average datum results from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

As described previously,22,36 periods of immobility lasting ≥ 5 min were defined as sleep and were computed using an Excel software macro from P.J. Shaw laboratory.

Sleep Deprivation

Flies were sleep deprived using the sleep nullifying apparatus (SNAP), an automated sleep deprivation apparatus that has been found to keep flies awake without nonspecifically activating stress responses.37 SNAP tilted asymmetrically from −60° to +60° such that sleeping flies were displaced during the downward movement 3 times per 30 seconds. During the 4 h of sleep deprivation, the SNAP was “on” during 30 sec each 5 min. For the stimulation control, flies were submitted to mechanical stimulation during 12 min per hour. During these 12 min, the SNAP was “on” during 30 sec each minute. This stimulation was applied during 4 h to mimic the sleep deprivation protocol. Thus, flies were submitted to the same amount of mechanical stimulation as during the sleep deprivation protocol but during a shorter period. Flies were able to sleep up to 48 min per hour during those 4 h.

To estimate the quantity and quality of sleep lost during the sleep deprivation, the total amount of sleep was calculated for undisturbed conditioned control flies during the same period as sleep deprivation of the sleep-deprived groups.

Statistical Analyses

All average data are presented as mean ± SEM and compared with 2-tailed unpaired t-tests. Tests were performed using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

RESULTS

Sleep Requirement during ARM Consolidation

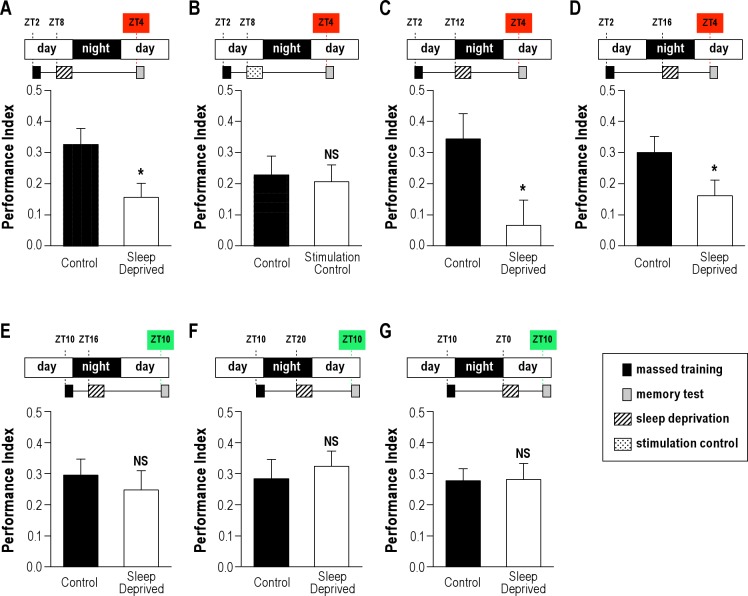

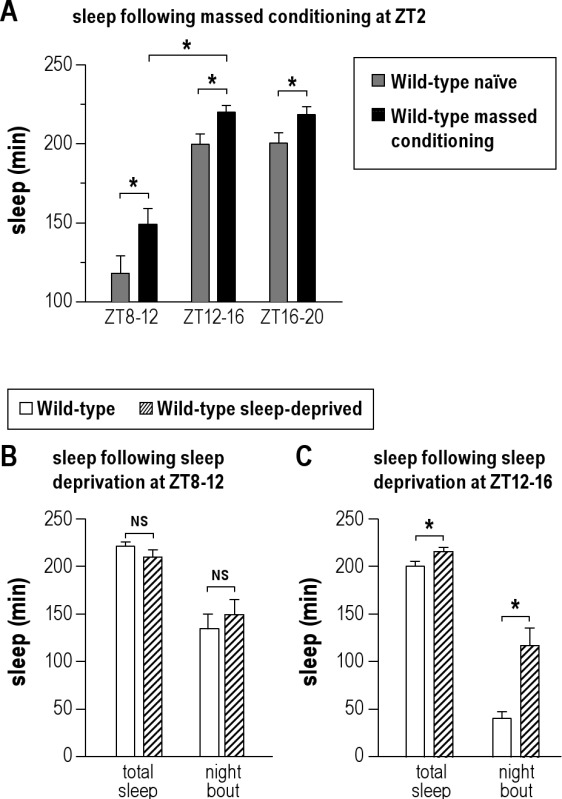

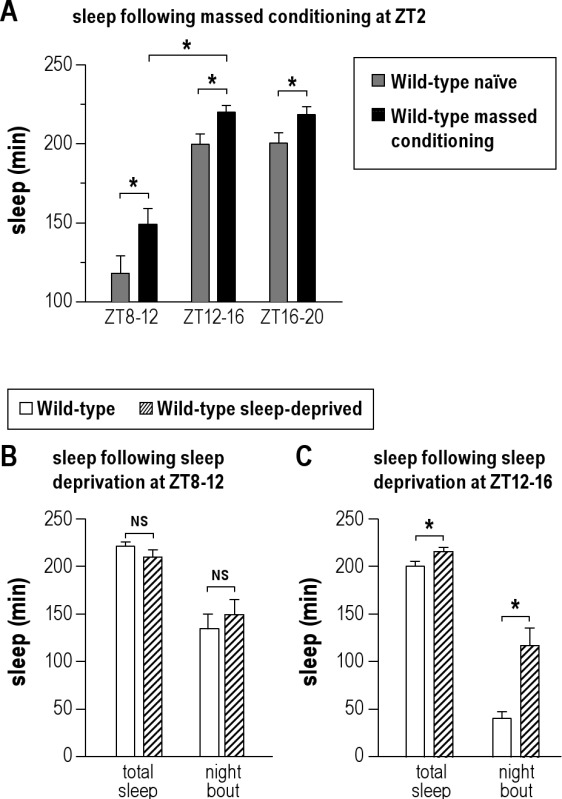

To evaluate whether sleep is required for ARM processing, we analyzed ARM performance of wild-type flies sleep deprived during the memory consolidation phase. For that purpose, groups of flies were first trained in the morning, zeitgeber time 2 (ZT2), with 5 massed-cycle conditioning (massed training). Then half of the flies were transferred to trikinetics tubes and left there without perturbation (control group), while the other half were transferred to trikinetics tubes and submitted to 4 h of sleep deprivation. Given the time required to transfer each fly in individual tubes after the training, and to insure synchronicity of treatment for all the flies, the sleep deprivation was scheduled 4 h after conditioning. When the sleep deprivation treatment was applied for 4 h at ZT8, we observed that memory scores of sleep-deprived groups were significantly lower than that of control groups (Figure 1A). Wild-type flies are predominantly awake during the hours preceding lights-off.38 However, trained flies obtained on average 148 ± 10 min of sleep from ZT8 to ZT12 (Figure S1A). Interestingly, trained flies exhibited significantly more sleep than näive flies, indicating that conditioning treatment led to an increase in sleep (Figure S1A). Thus, trained flies experienced a substantial amount of sleep during the 4 h preceding lights-off, while sleep-deprived flies were maintained awake during the same period. Following sleep deprivation, the quantity of sleep as well as its quality, as measured by mean bout duration, were similar to that observed in non–sleep-deprived flies and did not show detectable evidence of a sleep homeostatic response; this may be due to the relative low level of sleep lost (Figure S1B).

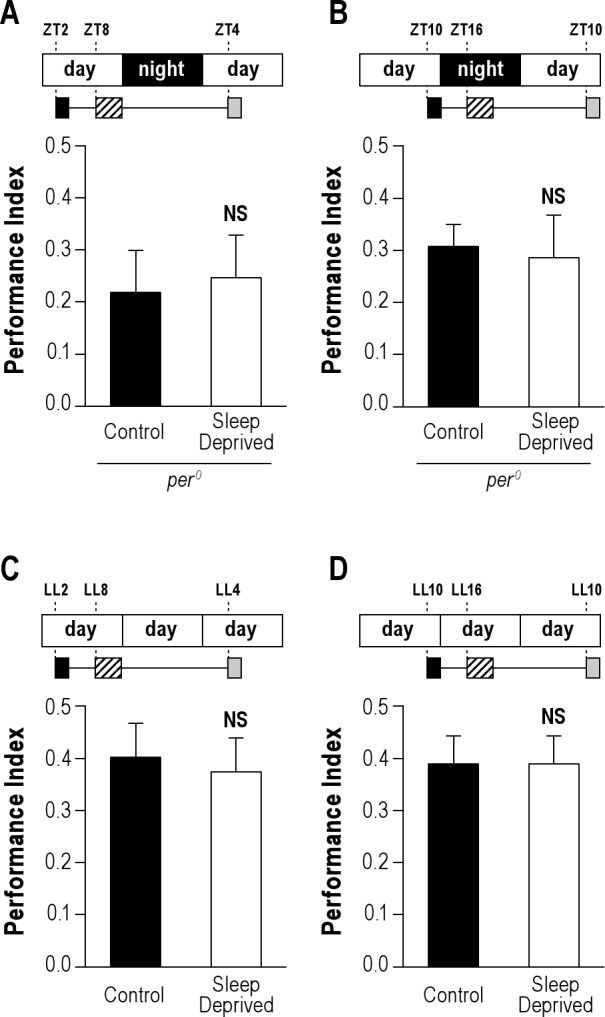

Figure 1.

Effect of sleep deprivation during ARM consolidation. Wild-type flies were trained with 5 massed cycles, either sleep deprived or submitted to a mechanical control, and tested at times indicated in the cartoon above each graph. Control groups correspond to flies in trikinetics tubes without any perturbation. (A, C, D) Sleep deprivations from 4 to 16 h after the end of the conditioning disrupt ARM when training and testing occur in the morning (n ≥ 12). (B) Mechanical control, flies received the same amount of mechanical stimulation as during the sleep deprivation, but over a shorter period (see Methods). Flies exhibit a normal ARM (n = 12). We note that the memory score generated by the control groups is lower than in the previous experiment, due to common variability in behavior experiments. (E, F, G) Sleep deprivations from 4 to 16 h after the end of the conditioning do not disrupt ARM scores when training and testing occur in the evening (ZT10) (n ≥ 12). Data are mean PI ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05); * (P < 0.05).

Sleep-deprived and control flies displayed similar amounts of sleep at the time of the test from ZT4 to ZT5 (41.5 ± 4.5 min and 38.8 ± 4.3 min, respectively; t-test; n = 12; P = 0.78); thus, increased sleepiness during the test is an unlikely explanation for the memory defects observed in sleep-deprived flies. Moreover, it has been shown that flies can recover normal cognitive performance in as little as 2 h following 12 h of sleep deprivation.28

Several reports have shown that memory and learning defects induced by sleep deprivation are not caused by the stress produced by the mechanical perturbation used during the sleep deprivation protocol.30,31 To formally exclude that a stress induced by the sleep deprivation protocol could be responsible for the observed memory impairment, we performed a stimulation control. Flies were submitted to the same amount of mechanical stimulation as during the 4-h sleep deprivation protocol, but during a shorter period of time. Importantly, unlike the sleep deprivation protocol, this control treatment allowed flies to rest and sleep during 48 min per hour. Flies submitted to this protocol showed memory scores similar to that of the undisturbed groups (Figure 1B). Taken together, the results strongly suggest that the memory defect observed in Figure 1A experiment is specifically caused by sleep disruption.

To further determine the window during which ARM consolidation is dependent on sleep, we delayed the beginning of sleep deprivation to either 8 h or 12 h after the end of the conditioning. In both cases, we observed a 24-h ARM defect (Figures 1C, D). Sleep monitoring revealed that at ZT12-16 and ZT16-20, trained flies experienced 220 ± 4 min and 219 ± 5 min of sleep, respectively, amounts significantly higher than that observed in näive flies (Figure S1A). Moreover, following treatment, sleep-deprived flies exhibited an increase in the amount and quality of sleep compared to control flies (Figure S1C), indicating a sleep homeostatic response.

Altogether the data indicate that ARM, a consolidated memory form that does not rely on de novo protein synthesis, is sensitive to 4 h of sleep deprivation occurring in a time window ranging from 4 to 16 h after conditioning.

The Time of Day Influences ARM Performance after Sleep Deprivation

Because Drosophila olfactory learning can be influenced by the time of day,39 we next sought to evaluate whether circadian rhythms could influence ARM performance after sleep deprivation. For that purpose, training sessions were performed at the end of the lights-on period (evening), ZT10 (Figures 1E-G), instead of ZT2 (morning) (Figures 1A, C, D). Flies were then sleep deprived for 4 h starting at ZT16, and tested for memory retrieval at ZT10 the next day. Strikingly, sleep-deprived flies did not show any significant memory impairment (Figure 1E). Similar results were observed when the sleep deprivation window was shifted to either ZT20 or ZT0 (Figures 1F, G). Thus, flies conditioned and further tested in the evening exhibit a memory performance that is not affected by sleep deprivation, suggesting that performance after sleep deprivation is modulated by circadian rhythms.

Memory Retrieval Is Modulated by the Circadian Cycle in Sleep-Deprived Flies

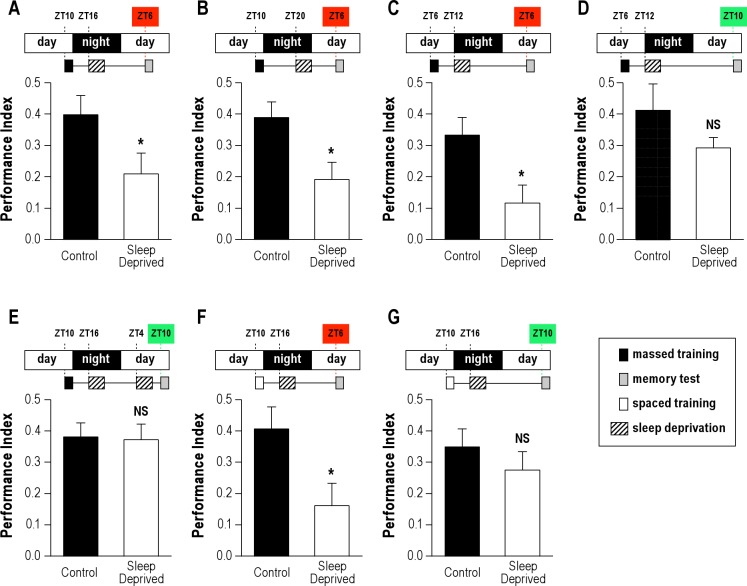

To determine whether conditioning and/or testing in the evening was responsible for the loss of ARM sensitivity to sleep deprivation, flies were submitted to sleep deprivation after conditioning performed at ZT10, but were tested for retrieval at ZT6, 20 h later, instead of 24 h (Figure 2A). In that case, sleep-deprived flies displayed an ARM impairment (Figure 2A). This defect was not correlated to the sleep deprivation time window, as we obtained similar results with a sleep deprivation taking place 4 h later (Figure 2B), indicating that ARM performance defects following sleep deprivation depends on when retrieval takes place. The shorter time interval between the end of the sleep deprivation and the retrieval test is unlikely to cause the impairment, as we observed in our initial set of experiments that a 6-h interval between sleep deprivation and testing does not lead to performance impairment (Figure 1G).

Figure 2.

The time of day affects memory retrieval following sleep deprivation.(A-E) Wild-type flies were trained with 5 massed cycles for ARM analyses. (A, B) Flies sleep deprived for 4 h and tested 20 h after training (ZT6) exhibit a memory impairment compared to control groups (n ≥ 14). (C) Flies sleep deprived for 4 h and tested 24 h after training (ZT6) exhibit memory impairment compared to control groups (n = 12). (D) Flies sleep deprived for 4 h and tested 28 h after training (ZT10) display a wild-type ARM (n = 12). (E) Flies were sleep deprived twice. A first sleep deprivation was applied from ZT16 to ZT20, and a second one the next day from ZT4 to ZT8. Flies were tested for memory performance at ZT10. Sleep-deprived flies exhibit memory scores indistinguishable from control flies (n = 11). (F, G) Flies were trained with 5 spaced cycles for LTM analyses. (F) Flies sleep deprived for 4 h and tested 20 h after training (ZT6) exhibit a memory impairment compared to control groups (n = 9). (G) Flies sleep deprived for 4 h and tested 24 h after training (ZT10) display a wild-type LTM (n = 12, P > 0.05). Data are mean PI ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05); * (P < 0.05).

To confirm these results, we next performed the opposite experiment, namely a conditioning at ZT6, and a memory test taking place either 24 h later at ZT6 (Figure 2C), or 28 h later at ZT10 (Figure 2D). In other words, experiments were identical except for the time of test. Strikingly, flies tested at ZT6 displayed a memory defect (Figure 2C), while flies tested at ZT10 exhibited scores comparable to those of control flies (Figure 2D).

When flies were tested at ZT10—the end of the light phase—they had more lights-on time to possibly recover from sleep deprivation. To exclude the possibility that the longer recovery period might account for the absence of memory deficits, we applied a second sleep deprivation before the test, from ZT4 to ZT8 (Figure 2E). Interestingly, flies that were sleep deprived twice exhibited normal memory scores when memory was tested at ZT10, indicating that increased opportunity to sleep was not responsible for better memory scores. We conclude that when the memory test occurs at the end of the light phase, ARM performance does not appear to be affected by a previous sleep deprivation.

As memory retrieval seems to be facilitated in the evening, one could expect that flies without sleep deprivation display higher memory scores when tested during this period (ZT10) rather than in the morning (ZT4). This was not the case, as we observed similar scores for all memory tests performed at ZT4 compared to those performed at ZT10 (PI(ZT4; n = 58) = 0.30 ± 0.03 and PI(ZT10; n = 56) = 0.31 ± 0.03; t-test: P > 0.05).

We next examined whether a circadian modulation of memory performance following sleep deprivation also applies to LTM, the other form of consolidated memory described in flies. Flies were submitted to a 5 spaced-cycle conditioning, a protocol known to generate LTM, then sleep deprived 4 h later for 4 h, and tested for memory retrieval either at ZT6 or at ZT10. When memory tests were performed at ZT6, we observed a LTM-impairment (Figure 2F), whereas in sharp contrast, flies displayed wild-type memory scores when tested at ZT10 (Figure 2G). These results suggest that, similar to ARM, LTM retrieval is affected by sleep deprivation taking place during the consolidation phase, except when memory retrieval occurs in the 2 h before lights-off.

Sleep Deprivation Does Not Disrupt ARM in Arrhythmic Flies

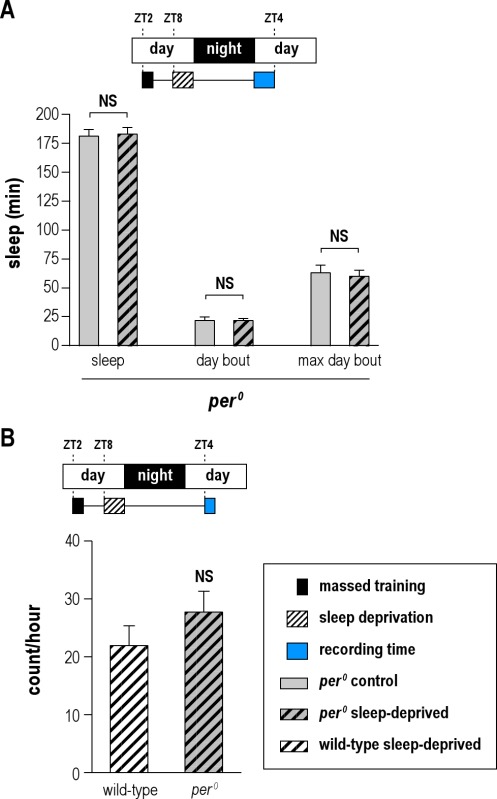

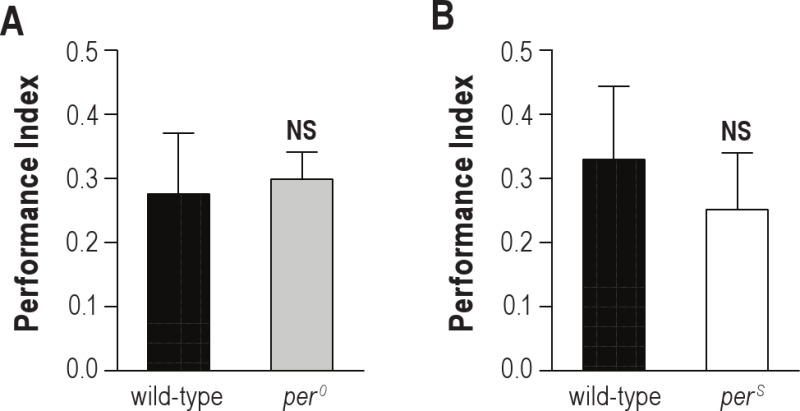

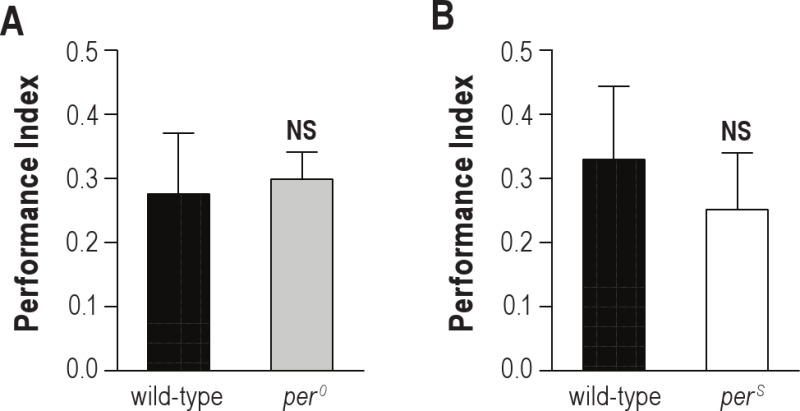

To further investigate the circadian modulation of ARM vulnerability to sleep deprivation, we evaluated per0 mutant flies which have been shown to lack a circadian clock.33,40–43 As previously observed, per0 flies did not anticipate the light-dark transition, but appeared to sleep less in the presence of light, and more in its absence (Figure S2A). Because per0 mutant exhibits a LTM courtship defect,44 we first checked 24-h memory after massed training. per0 flies exhibited normal performance (Figure S3A). Interestingly, when per0 flies reared under LD condition were trained using massed training and then submitted to 4 h sleep deprivation, they displayed normal scores no matter the training/testing time (Figures 3A, B). These results cannot be explained by a reduction in the amount of sleep lost during sleep deprivation, as quantification revealed that per0 flies (Figure 3A) lost slightly more sleep than wild-type flies sleep deprived at the same time of day (Figure 1A) (175 ± 2 min vs 166 ± 3 min; t-test; n = 384; P = 0.0041). Moreover, the quality of removed sleep was similar in these 2 conditions: mean average sleep bout duration was 36.0 ± 2.3 min for wild-type in LD vs 33.5 ± 2.1 min for per0 flies (t-test; n = 384; P > 0.05). Sleep deprived per0 flies did not obtain more sleep than undisturbed flies in the hours preceding the test (ZT0-4) (Figure S4A). In addition, we observed similar locomotor activity in sleep-deprived per0 and sleep-deprived wild-type flies at ZT4, the moment of the memory test (Figure S4B). Thus, increased sleep or activity does not explain the lack of memory deficits in sleep-deprived per0 flies. In conclusion, ARM is not sensitive to a 4 h sleep deprivation taking place during the consolidation phase in per0 mutant flies.

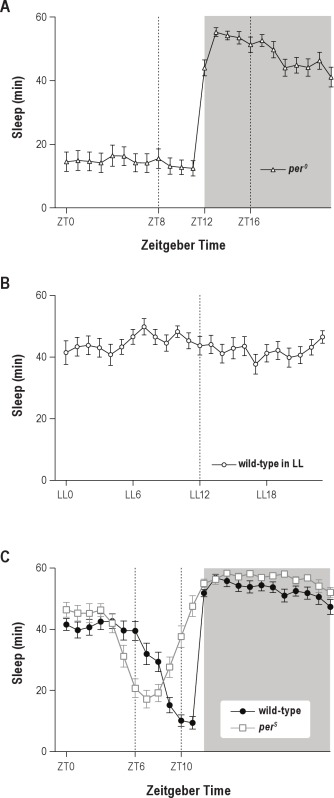

Figure 3.

4 h of sleep deprivation does not disrupt ARM in arrhythmic flies. Flies were conditioned with 5 massed cycles and submitted to a 4-h sleep deprivation 4 h later.(A, B) per0 mutant flies. When per0 flies were either trained and tested in the morning, or trained and tested in the evening (ZT10), sleep-deprived groups show no memory impairment (n ≥ 11). (C, D) Wild-type flies in constant light (LL). Wild-type flies were raised in LD cycles and placed in LL condition from emergence to the memory test. When flies were sleep deprived 4 h after the end of massed training, ARM is not disturbed (n ≥ 11). Data are mean PI ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

To further evaluate the impact of circadian rhythms on consolidated memory retrieval, we next disrupted the circadian clock by placing wild-type flies in constant light (LL).38,45,46 Under LL condition, flies were arrhythmic with respect to sleep pattern (Figure S2B) and able to form 24-h memory after massed training (Figures 3C, D). We next evaluated ARM after massed training either at LL2 or LL10, followed by sleep deprivation taking place 4 h later (Figures 3C, D). Memory tests performed 24 h later revealed that, similar to per0 flies, wild-type LL flies showed normal memory retrieval after sleep deprivation (Figures 3C, D). Again, these results cannot be explained by a reduction in the amount of sleep lost, as flies in LL lost more sleep during sleep deprivation (Figure 3C) than flies kept in LD and sleep deprived at ZT8 (Figure 1A) (183 ± 2 min vs 166 ± 3 min; t-test; n = 384; P < 0.0001). Moreover, the quality of removed sleep was similar in these 2 conditions as mean average sleep bout duration was 36.0 ± 2.3 min for wild-type in LD vs 36.7 ± 2.1 min for wild-type in LL (t-test; n = 384; P > 0.05). Taken together, the results indicate that disruption of circadian rhythms reduces sleep requirement for ARM.

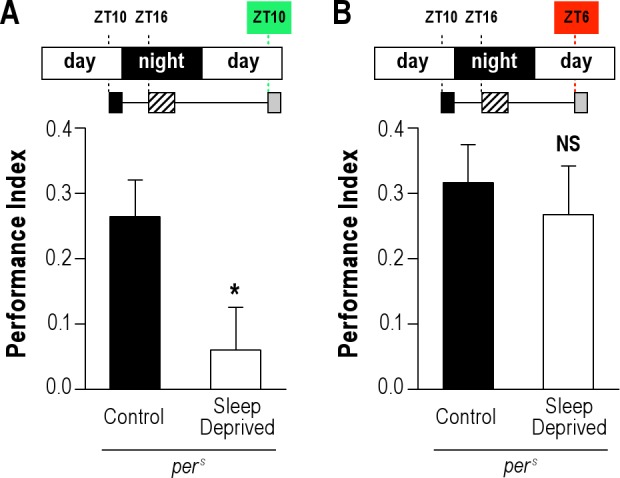

ARM Performance after Sleep Deprivation Is Modulated by the Evening Waking Peak

The circadian clock modulates the intensity of locomotor activity throughout the day, driving notably well-identified morning and evening peaks of activity and wake, the former occurring after lights-on, and the latter a couple of hours before lights-off.38,47,48 To assess the role of the evening waking peak during memory retrieval, we used perS mutant flies.33 Under LD condition, perS flies displayed an evening waking peak occurring 4 h earlier than that observed in wild-type flies (Figure S2C), due to a shorter circadian period (19 h).33 We first checked that perS mutant displayed normal 24 h memory (Figure S3B). Next, perS mutant flies underwent massed training and were submitted to 4-h sleep deprivation 4 h later. Strikingly, perS flies exhibited a memory deficit when the training/testing occurred at ZT10 (Figure 4A), unlike wild-type flies (Figure 1E). In sharp contrast, when the testing occurred at ZT6, during their waking peak, perS flies exhibited memory scores that were not significantly different from the control (Figure 4B). Because we raised flies at 18°C, we could not assess the role of the morning activity peak, as low temperatures have been shown to inhibit this activity peak.49 In conclusion, the results show that when memory retrieval takes place during the circadian waking peak, memory retrieval is not affected by sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase.

Figure 4.

Positive correlation between memory retrieval after sleep deprivation and the evening activity peak. perS mutant flies were trained with 5 massed cycles in the evening (ZT10) and sleep deprived 4 h after conditioning. (A) When tested for memory at ZT10, sleep-deprived perS flies exhibit a significant defect (n = 12). (B) When tested at ZT6, sleep-deprived perS flies show a wild-type ARM (n ≥ 11). Data are mean PI ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05); * (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that 4 h of sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase affects aversive olfactory ARM and LTM, showing the importance of sleep for distinct types of memory. When memory retrieval occurs during the evening waking peak, however, normal performance is observed after sleep deprivation, suggesting that circadian factors modulate the amplitude of the observed sleep deprivation induced deficits. Interestingly, we show that disruption of the circadian clock reduces sleep requirement during consolidation.

Ganguly-Fitzgerald et al. previously showed that 4 h of sleep deprivation 4 h after conditioning induces a LTM courtship defect.31 LTM relies on transcriptome changes and de novo protein synthesis, probably mediating synaptic plasticity. Despite the fact that ARM is a consolidated memory form that is less energetically costly than LTM, we show here that this process does also require sleep, suggesting a requirement for sleep-induced synaptic plasticity. It is known that LTM consolidation is a long process occurring from 0 to at least 24 h after conditioning, observed as changes in gene expression50 and the identification of specific memory traces.51 In contrast, very few data are available about ARM consolidation. Our results suggest that ARM consolidation is also a long process, as sleep deprivation starting 12 h after training led to memory impairment. Whether or not ARM and LTM rely on the same or unrelated sleep-dependent processes for their consolidation remains to be investigated. One interesting pathway in that regards is the cAMP signaling cascade, which plays a key role in all those processes.19,52,53

In Drosophila as in mammals, memory performance can be modulated by circadian factors. In fly, learning achieved by association of an odor with the delivery of a single electric shock has been shown to be more robust during the early night (ZT13).39 In the present study, however, flies were conditioned either at ZT2, 6, or 10, several hours away from the optimum learning window defined by Lyons and Roman. In addition, our results show that memory performance of the sleep-deprived flies was modulated by the testing time and not by the learning time.

It is well known that flies sleep less and exhibit a locomotor activity peak 2-3 h prior to lights-off as they anticipate night. Here, we show that testing memory performance during this activity and waking peak can compensate for the detrimental effect of sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase. Similar results were obtained for LTM processing, suggesting that similar mechanisms might link memory retrieval and circadian rhythms for both ARM and LTM. Importantly, we can exclude that memory scores are modulated by a change in sensory perception. Indeed, it has been shown that olfactory responses in wild-type flies peak during the middle of the night, and that there is no variation between midday and evening.54 Moreover, this peak does not correlate with the locomotor activity peak,55 ruling out that increased sensory perception might account for normal memory performance after sleep deprivation when retrieval is achieved in the evening.

Memories are not acquired in their definitive form, but undergo a gradual process of stabilization over time. Sleep is believed to play a role in progressively increasing the strength and stability of connections that represent the original experience.56,57 It seems unlikely that a sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase, and ending from 8 to 16 h before the memory test, would affect only the retrieval step. Rather, we suggest that our data reveal two phenomena: (1) a consolidation phase that is affected by a sleep deprivation, pointing to a role for sleep in that process, and (2) memory retrieval that is modulated by the time of day, pointing to a role for circadian rhythms in that process. Thus, one could hypothesize that if flies are sleep deprived during the memory consolidation phase, there might be a deficit in the consolidation and/or selection of connections relevant to memory, so that it is more difficult for the animal to retrieve the appropriate information. However, memory retrieval might occur more efficiently during the fly activity peak, thus bypassing the detrimental effect caused by the sleep deprivation, revealing an interaction between the consolidation and retrieval steps. We do not know whether the circadian modulation relies on the clock mechanisms per se, or maybe more likely, on a general brain state of alert flies that would facilitate memory retrieval.

Circadian rhythms are basic biological phenomena that exist throughout phylogeny. Studies in several species have shown that disruption of circadian rhythms has negative consequences on memory.58 Unexpectedly, disrupting the fly circadian clock with either LL condition or the per0 mutation does not affect 24-h ARM; moreover, the generated memory is not sensitive to 4 h of sleep deprivation during the consolidation phase. As mentioned above, this is not attributable to a change in either sleep architecture or general activity during the memory test. Rather, the results indicate a lower sleep requirement for ARM when circadian rhythms are disrupted. It is possible that the lack of circadian clock relaxes time constraints on sleep-dependent synaptic processes and renders memory consolidation less sensitive to sleep disruption. Nevertheless, per0 flies display a sleep homeostatic response and performance impairments following sleep deprivation, as do wild-type flies.37,59 While sleep homeostatic regulation can occur in the absence of a functional circadian clock, the study of clock mutants such as tim01 and cyc01 indicate that the homeostatic response and thus potentially sleep requirements can be positively or negatively modulated by molecular components of the clock.21,22,37

In conclusion, this work points toward a correlation between circadian rhythm and sleep requirement for consolidated memories. Elucidating how the circadian clock influences sleep requirements and memory retrieval is clearly a complex issue that will require further investigations.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Fraņcois Rouyer (INAF, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) for helpful comments during this work, and for providing the per0 and perS lines. We also thank members of the Genes and Dynamics of Memory Systems group for critical reading of the manuscript. Mr. Le Glou was supported by a fellowship from the French Minist̀ere de la Recherche et de l'Enseignement, and Dr. Seugnet by a fellowship from the Fondation Pierre-Gilles de Gennes.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Sleep analyses. Wild-type 3-4 days old flies were trained with massed conditioning protocol at ZT2. (A) Sleep analyses in trained flies. Total amount of sleep was monitored during the 4 h-windows corresponding to the different time-windows used to apply sleep deprivation in Figure 1. Näive wild-type flies (gray bars) and trained flies (black bars). Conditioning induces an increase in total sleep (ZT8-12, 26%; ZT12-16, 11% and ZT16-20, 11%; n = 32). (B,C) Sleep quantification in trained flies, in the 4 h following the sleep deprivation treatment. Hatched bars: sleep-deprived flies; white bars: flies kept in trikinetics tubes without any perturbation. (B) Sleep deprivation applied from ZT8 to ZT12 does not induce any change in either sleep quantity or sleep quality (n = 32). (C) Sleep deprivation applied from ZT12 to ZT16 induces an increase in sleep quantity and quality (n = 32). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05), *(P < 0.05).

Sleep pattern analyses. (A) per0 mutant flies in LD cycles. Daily sleep patterns (min/h) (n = 32). per0 flies show no circadian regulation of sleep behavior beyond the fact that they sleep less during the day due to light exposure. (B) Wild-type flies in constant light (LL). Daily sleep patterns (min/h) (n = 32). Wild-type flies show no circadian regulation of sleep behavior. (C) Daily sleep patterns (min/h) in LD cycles for wild-type (n = 32) and perS (n = 32) flies. Wild-type flies sleep less around ZT10, whereas perS mutant flies sleep less around ZT6. Data are mean ± SEM.

Circadian mutants exhibit normal ARM. 1-2 days old flies were trained with 5 massed cycles and tested for memory 24 h later. (A) per0 mutant flies exhibit normal scores (n ≥ 9). (B) perS mutant flies exhibit normal scores (n ≥ 7). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Sleep and locomotor activity in sleep-deprived per0 flies. Flies were trained with massed conditioning protocol at ZT2. (A) Sleep was monitored inper0 flies that were either sleep-deprived from ZT8 to ZT12 or kept undisturbed. Sleep deprivation did not induce any change in either sleep quantity or sleep quality during the first 4 h of the light period (n = 32). (B) Wild-type and per0 flies were sleep-deprived from ZT8 to ZT12 and locomotor activity was monitored from ZT4 to ZT6 the next day (count/hour: number of infrared beam breaks per h). per0 flies did not show any increase in locomotor activity compared to wild-type flies (n ≥ 54). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang G, Grone B, Colas D, Appelbaum L, Mourrain P. Synaptic plasticity in sleep: learning, homeostasis and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:452–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graves LA, Heller EA, Pack AI, Abel T. Sleep deprivation selectively impairs memory consolidation for contextual fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2003;10:168–76. doi: 10.1101/lm.48803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vecsey CG, Baillie GS, Jaganath D, et al. Sleep deprivation impairs cAMP signalling in the hippocampus. Nature. 2009;461:1122–5. doi: 10.1038/nature08488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith C, Rose GM. Evidence for a paradoxical sleep window for place learning in the Morris water maze. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:93–7. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith C, Rose GM. Posttraining paradoxical sleep in rats is increased after spatial learning in the Morris water maze. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:1197–204. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.6.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hairston IS, Little MT, Scanlon MD, et al. Sleep restriction suppresses neurogenesis induced by hippocampus-dependent learning. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4224–33. doi: 10.1152/jn.00218.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito K, Okada R, Tanaka NK, Awasaki T. Cautionary observations on preparing and interpreting brain images using molecular biology-based staining techniques. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;62:170–86. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peschel N, Helfrich-Forster C. Setting the clock--by nature: circadian rhythm in the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1435–42. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushey D, Cirelli C. From genetics to structure to function: exploring sleep in Drosophila. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;99:213–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387003-2.00009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahsai L, Zars T. Learning and memory in Drosophila: behavior, genetics, and neural systems. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;99:139–67. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387003-2.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Littleton JT, Ganetzky B. Ion channels and synaptic organization: analysis of the Drosophila genome. Neuron. 2000;26:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tully T, Preat T, Boynton SC, Del Vecchio M. Genetic dissection of consolidated memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mery F, Kawecki TJ. A cost of long-term memory in Drosophila. Science. 2005;308:1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1111331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Structural changes accompanying memory storage. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:397–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuire SE, Le PT, Davis RL. The role of Drosophila mushroom body signaling in olfactory memory. Science. 2001;293:1330–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1062622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isabel G, Pascual A, Preat T. Exclusive consolidated memory phases in Drosophila. Science. 2004;304:1024–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1094932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernabeu R, Bevilaqua L, Ardenghi P, et al. Involvement of hippocampal cAMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathways in a late memory consolidation phase of aversively motivated learning in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourtchouladze R, Abel T, Berman N, Gordon R, Lapidus K, Kandel ER. Different training procedures recruit either one or two critical periods for contextual memory consolidation, each of which requires protein synthesis and PKA. Learn Mem. 1998;5:365–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perazzona B, Isabel G, Preat T, Davis RL. The role of cAMP response element-binding protein in Drosophila long-term memory. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8823–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4542-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenspan RJ, Tononi G, Cirelli C, Shaw PJ. Sleep and the fruit fly. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:142–5. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendricks JC, Finn SM, Panckeri KA, et al. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron. 2000;25:129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80877-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:1834–7. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Swinderen B, Nitz DA, Greenspan RJ. Uncoupling of brain activity from movement defines arousal States in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2004;14:81–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cirelli C, LaVaute TM, Tononi G. Sleep and wakefulness modulate gene expression in Drosophila. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1411–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerman JE, Rizzo W, Shockley KR, et al. Multiple mechanisms limit the duration of wakefulness in Drosophila brain. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27:337–50. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00030.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joiner WJ, Crocker A, White BH, Sehgal A. Sleep in Drosophila is regulated by adult mushroom bodies. Nature. 2006;441:757–60. doi: 10.1038/nature04811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitman JL, McGill JJ, Keegan KP, Allada R. A dynamic role for the mushroom bodies in promoting sleep in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;441:753–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seugnet L, Suzuki Y, Vine L, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. D1 receptor activation in the mushroom bodies rescues sleep-loss-induced learning impairments in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bushey D, Huber R, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Drosophila Hyperkinetic mutants have reduced sleep and impaired memory. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5384–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0108-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Yu F, Guo A. Sleep deprivation specifically impairs short-term olfactory memory in Drosophila. Sleep. 2009;32:1417–24. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.11.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganguly-Fitzgerald I, Donlea J, Shaw PJ. Waking experience affects sleep need in Drosophila. Science. 2006;313:1775–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donlea JM, Thimgan MS, Suzuki Y, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. Inducing sleep by remote control facilitates memory consolidation in Drosophila. Science. 2011;332:1571–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1202249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konopka RJ, Benzer S. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:2112–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascual A, Preat T. Localization of long-term memory within the Drosophila mushroom body. Science. 2001;294:1115–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tully T, Quinn WG. Classical conditioning and retention in normal and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Physiol A. 1985;157:263–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01350033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andretic R, Shaw PJ. Essentials of sleep recordings in Drosophila: moving beyond sleep time. Methods Enzymol. 2005;393:759–72. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw PJ, Tononi G, Greenspan RJ, Robinson DF. Stress response genes protect against lethal effects of sleep deprivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;417:287–91. doi: 10.1038/417287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamblen-Coyle MJ, Wheeler DA, Rutila JE, Rosbash M, Hall JC. Behavior of period-altered circadian rhythm mutants of Drosophila in light: Dark cycles (Diptera: Drosophilidae) J Insect Behav. 1992;5:417–46. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyons LC, Roman G. Circadian modulation of short-term memory in Drosophila. Learn Mem. 2009;16:19–27. doi: 10.1101/lm.1146009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardin PE, Hall JC, Rosbash M. Feedback of the Drosophila period gene product on circadian cycling of its messenger RNA levels. Nature. 1990;343:536–40. doi: 10.1038/343536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sehgal A, Price JL, Man B, Young MW. Loss of circadian behavioral rhythms and per RNA oscillations in the Drosophila mutant timeless. Science. 1994;263:1603–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8128246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sehgal A, Rothenfluh-Hilfiker A, Hunter-Ensor M, Chen Y, Myers MP, Young MW. Rhythmic expression of timeless: a basis for promoting circadian cycles in period gene autoregulation. Science. 1995;270:808–10. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter-Ensor M, Ousley A, Sehgal A. Regulation of the Drosophila protein timeless suggests a mechanism for resetting the circadian clock by light. Cell. 1996;84:677–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakai T, Tamura T, Kitamoto T, Kidokoro Y. A clock gene, period, plays a key role in long-term memory formation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16058–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401472101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konopka RJ, Pittendrigh C, Orr D. Reciprocal behaviour associated with altered homeostasis and photosensitivity of Drosophila clock mutants. J Neurogenet. 1989;6:1–10. doi: 10.3109/01677068909107096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Power JM, Ringo JM, Dowse HB. The effects of period mutations and light on the activity rhythms of Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Rhythms. 1995;10:267–80. doi: 10.1177/074873049501000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wheeler DA, Hamblen-Coyle MJ, Dushay MS, Hall JC. Behavior in light-dark cycles of Drosophila mutants that are arrhythmic, blind, or both. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8:67–94. doi: 10.1177/074873049300800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helfrich-Forster C. Differential control of morning and evening components in the activity rhythm of Drosophila melanogaster--sex-specific differences suggest a different quality of activity. J Biol Rhythms. 2000;15:135–54. doi: 10.1177/074873040001500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Liu Y, Bilodeau-Wentworth D, Hardin PE, Emery P. Light and temperature control the contribution of specific DN1 neurons to Drosophila circadian behavior. Curr Biol. 2010;20:600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubnau J, Chiang AS, Grady L, et al. The staufen/pumilio pathway is involved in Drosophila long-term memory. Curr Biol. 2003;13:286–96. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu D, Akalal DB, Davis RL. Drosophila alpha/beta mushroom body neurons form a branch-specific, long-term cellular memory trace after spaced olfactory conditioning. Neuron. 2006;52:845–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hendricks JC, Williams JA, Panckeri K, et al. A non-circadian role for cAMP signaling and CREB activity in Drosophila rest homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1108–15. doi: 10.1038/nn743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horiuchi J, Yamazaki D, Naganos S, Aigaki T, Saitoe M. Protein kinase A inhibits a consolidated form of memory in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810119105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krishnan B, Dryer SE, Hardin PE. Circadian rhythms in olfactory responses of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1999;400:375–8. doi: 10.1038/22566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou X, Yuan C, Guo A. Drosophila olfactory response rhythms require clock genes but not pigment dispersing factor or lateral neurons. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:237–44. doi: 10.1177/0748730405274451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bushey D, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: structural evidence in Drosophila. Science. 2011;332:1576–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1202839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerstner JR, Yin JC. Circadian rhythms and memory formation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:577–88. doi: 10.1038/nrn2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thimgan MS, Suzuki Y, Seugnet L, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. PLoS Biol. 2010. The perilipin homologue, lipid storage droplet 2, regulates sleep homeostasis and prevents learning impairments following sleep loss; p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sleep analyses. Wild-type 3-4 days old flies were trained with massed conditioning protocol at ZT2. (A) Sleep analyses in trained flies. Total amount of sleep was monitored during the 4 h-windows corresponding to the different time-windows used to apply sleep deprivation in Figure 1. Näive wild-type flies (gray bars) and trained flies (black bars). Conditioning induces an increase in total sleep (ZT8-12, 26%; ZT12-16, 11% and ZT16-20, 11%; n = 32). (B,C) Sleep quantification in trained flies, in the 4 h following the sleep deprivation treatment. Hatched bars: sleep-deprived flies; white bars: flies kept in trikinetics tubes without any perturbation. (B) Sleep deprivation applied from ZT8 to ZT12 does not induce any change in either sleep quantity or sleep quality (n = 32). (C) Sleep deprivation applied from ZT12 to ZT16 induces an increase in sleep quantity and quality (n = 32). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05), *(P < 0.05).

Sleep pattern analyses. (A) per0 mutant flies in LD cycles. Daily sleep patterns (min/h) (n = 32). per0 flies show no circadian regulation of sleep behavior beyond the fact that they sleep less during the day due to light exposure. (B) Wild-type flies in constant light (LL). Daily sleep patterns (min/h) (n = 32). Wild-type flies show no circadian regulation of sleep behavior. (C) Daily sleep patterns (min/h) in LD cycles for wild-type (n = 32) and perS (n = 32) flies. Wild-type flies sleep less around ZT10, whereas perS mutant flies sleep less around ZT6. Data are mean ± SEM.

Circadian mutants exhibit normal ARM. 1-2 days old flies were trained with 5 massed cycles and tested for memory 24 h later. (A) per0 mutant flies exhibit normal scores (n ≥ 9). (B) perS mutant flies exhibit normal scores (n ≥ 7). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

Sleep and locomotor activity in sleep-deprived per0 flies. Flies were trained with massed conditioning protocol at ZT2. (A) Sleep was monitored inper0 flies that were either sleep-deprived from ZT8 to ZT12 or kept undisturbed. Sleep deprivation did not induce any change in either sleep quantity or sleep quality during the first 4 h of the light period (n = 32). (B) Wild-type and per0 flies were sleep-deprived from ZT8 to ZT12 and locomotor activity was monitored from ZT4 to ZT6 the next day (count/hour: number of infrared beam breaks per h). per0 flies did not show any increase in locomotor activity compared to wild-type flies (n ≥ 54). Data are mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05).