Abstract

Disruption of cell membranes by Aβ is believed to be one of the key components of Aβ toxicity. However, the mechanism by which this occurs is not fully understood. Here, we demonstrate that membrane disruption by Aβ occurs by a two-step process, with the initial formation of ion-selective pores followed by nonspecific fragmentation of the lipid membrane during amyloid fiber formation. Immediately after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1–40, defects form on the membrane that share many of the properties of Aβ channels originally reported from single-channel electrical recording, such as cation selectivity and the ability to be blockaded by zinc. By contrast, subsequent amyloid fiber formation on the surface of the membrane fragments the membrane in a way that is not cation selective and cannot be stopped by zinc ions. Moreover, we observed that the presence of ganglioside enhances both the initial pore formation and the fiber-dependent membrane fragmentation process. Whereas pore formation by freshly dissolved Aβ1–40 is weakly observed in the absence of gangliosides, fiber-dependent membrane fragmentation can only be observed in their presence. These results provide insights into the toxicity of Aβ and may aid in the design of specific compounds to alleviate the neurodegeneration of Alzheimer’s disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative disease characterized by memory loss and severe cognitive impairment. A key pathological marker of Alzheimer’s disease is the formation of extracellular plaques caused by the misfolding and aggregation of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides into extended fibrillar structures known as amyloid (1). Amyloid formation by Aβ1-40 is believed to be a key early stage in the development of Alzheimer’s, as Aβ1-40 aggregation has been repeatedly linked to neuronal dysfunction and death (2). The aggregation of Aβ1-40 generates a complex, multifactorial response in neurons, leaving the actual source of Aβ1-40 cytotoxicity unresolved. A number of studies have identified several factors that may contribute to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, including the generation of reactive oxygen species during aggregation, excessive aggregation of misfolded proteins leading to stress in the endoplasmic reticulum, inflammation, disruption of cellular membrane integrity, and activation of cell surface receptors that lead to cell death (2).

Although the exact mechanism by which Aβ causes neuronal death is not certain, one of the most clear and consistent pathologies in Alzheimer’s disease is an elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in the vicinity of Aβ amyloid deposits (3,4). The mechanism by which Aβ stimulates Ca2+ influx has not been fully elucidated, but it has been suggested that Aβ can directly disrupt membranes through the formation of ion channels (the channel hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease) (5). According to the channel hypothesis, small, annular oligomers of Aβ possessing a hydrophobic exterior and hydrophilic interior insert into the membrane, spanning the bilayer (6,7). The hollow structure of the oligomers allows ions to cross through the hydrophilic interior of the pore, causing an unregulated influx of Ca2+ into the cell. Because both neurons and mitochondria are highly sensitive to perturbations in ionic strength, a small perturbation in intracellular calcium levels caused by the unregulated Aβ channels can trigger an apoptotic cascade (8).

Experimental support for the channel hypothesis rests largely on atomic force microscopy (AFM), electron microscopy, and single-channel conductance measurements. Annular structures suggestive of ion channels were directly observed by AFM when Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 were reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers (7). The formation of these annular structures correlates with single-channel ion conductance measurements that showed stepwise current fluctuations suggestive of the formation of discrete pores (7,9–11). Like endogenous calcium channels, the channels formed by Aβ are charge and size selective, and can be blockaded by specific molecules that bind to the interior of the pore, such as Zn+2 (12–15). The ability of Aβ channels to be blockaded by Zn+2 suggests the involvement of a specific structure in membrane disruption, rather than a generalized disruption of the physical integrity of the bilayer.

Although the channel hypothesis accounts for many facets of Aβ toxicity through membrane disruption, some facets remain unexplained. First, large (up to 30 nm in diameter) spherical aggregates of Aβ have repeatedly been found to be toxic (16–18). This finding is surprising in light of the channel hypothesis, which would predict that such large spherical aggregates would not be able to form ion channels unless they disassemble into smaller aggregates. Second, aggregation of Aβ is often accompanied by large-scale morphological changes in the membrane that would not be expected by the insertion of small oligomeric pores (19–21). Rather, these large-scale morphological changes suggest that physical disruption of the membrane also takes place after prolonged incubation with Aβ, which may be a contributing factor in the toxicity of Aβ. It has been suggested that the elongation of existing fibrils adsorbed to the membrane can remove lipids from the membrane via a detergent-like mechanism, causing membrane disruption that could lead to cell death (22,23). However, the relationship between these two types of membrane disruption by Aβ and other amyloidogenic proteins has not been defined.

We show here through the use of model membrane systems that the mechanism of Aβ membrane disruption in vitro is likely to be mediated by a two-step process: 1), before fibril formation, soluble oligomers bind to the membrane to form small channel-like pores; and 2), Aβ fibril elongation causes membrane fragmentation through a detergent-like mechanism. Furthermore, we show that the fiber-dependent step of membrane disruption occurs only in the presence of gangliosides, whereas pore formation occurs at a low level in the absence of gangliosides.

Materials and Methods

Peptide preparation

To break up any preformed aggregates, Aβ1-40 was initially dissolved in NH3 2%v/v at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. The peptide was then lyophilized overnight and the powder obtained was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 500 μM. Each stock solution of Aβ1-40 was used immediately after preparation.

Dye leakage assay

Briefly, we added 1 or 2 μl of the peptide stock solution to 100 μl 6-carboxyfluorescein-filled large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC)/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS) 7:3, POPC/POPS/gangliosides 5.5:3:1.5, and total lipid brain extract (TLBE) for a final peptide concentration of 5 or 10 μM in Corning 96-well plates. Time traces were recorded at 25°C, and the samples were shaken for 10 s before each read. Full details of the liposome preparation and dye leakage assay can be found in the Supporting Material.

Thioflavin T assay

The kinetics of amyloid peptide formation were measured through increased fluorescence emission upon binding of amyloid fibers to the commonly used amyloid-specific dye thioflavin T (ThT). Samples were prepared by adding 1 or 2 μl of the peptide stock solution to 100 μl of the 10 mM phosphate buffer solution (100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 10 μM ThT) containing 0.2 mg/ml LUV, to yield a final peptide concentration of 5 or 10 μM, respectively. Details regarding the liposome preparation can be found in the Supporting Material. Experiments were carried out simultaneously with dye leakage samples using the same microplate and stock solution for each experiment.

Fura-2 assay

We detected the presence of cation- or size-selective pores by measuring changes in the 340:380 nm excitation ratio upon binding of Ca+2 or Zn+2 to the cation-sensitive dye Fura-2 encapsulated within the LUVs. Samples were prepared by first diluting the Fura-2 dye-filled vesicles solution with buffer solution (10 mM Hepes buffer solution, 100 μM Fura-2 pentapotassium salt, 200 μM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4; to prevent the formation of solid calcium phosphate, phosphate buffer was not used) to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml. Then, Aβ1-40 was added with a final concentration of 5 μM or 10 μM. Fluorescence was measured at 340 and 380 nm with slits set for 10 nm bandwidths to obtain the baseline. After 10 min, 500 μM of Ca+2 or Zn+2 were added to the sample, and changes in the 340:380 ratio were recorded. Samples with MSI-78, an antimicrobial peptide that is known to strongly disrupt membranes, were also run as a positive control.

Lipid sedimentation assay

We detected the presence of micelle formation by measuring the lipid concentration in the supernatant after sedimenting 1000 nm LUVs by centrifugation. Solutions of POPC/POPS 7:3, POPC/POPS/ganglioside 5.5:4:1.5, and TLBE LUVs at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml were prepared as described above, except that the solutions were extruded through 1000 nm membranes. We first incubated 20 μM Aβ1-40 with 250 μl of the LUV solution for 2 days to form amyloid fibers. After incubation with Aβ1-40, the samples were centrifuged for 40 min at 14,000 rpm, and the supernatant, which contained any resulting micelles, was collected, diluted in 1 ml of chloroform, and treated as described below to measure the lipid concentration in solution. Solutions without Aβ-40 were set as controls.

Lipid concentrations in the supernatant were detected via the Stewart assay, a colorimetric technique that is based on the ability of phospholipids to form a complex with ammonium ferrothiocyanate. Initially, a calibration curve was created for each LUV lipid composition. A series of chloroform solutions with known concentrations of lipids (each solution 1 ml) were prepared and treated with 1 ml of a solution containing ferric chloride and ammonium thiocyanate. Each solution was vortexed for 20 s and the organic phase was collected. The optical density of these standard solutions was at 461 nm, and was plotted versus the known lipid concentration and used as a calibration curve to determine the lipid concentrations in the supernatant.

31P solid-state NMR

All of the experiments were performed on an Agilent/Varian 400 MHz solid-state NMR spectrometer. A Varian temperature control unit was used to maintain the sample temperature at 37°C. All 31P spectra were collected using a spin-echo sequence (90°-tau-180°-tau with tau = 60 μs) under 25 kHz two-pulse phase modulation decoupling of protons. A typical 90° pulse length of 5 μs was used with a recycle delay of 3 s. The 31P chemical shift spectra are referenced with respect to 85% H3PO4 at 0 ppm. In each experiment, the 31P spectrum of 200 μL LUVs composed of 4 mg POPC/POPS or POPC/POPS/ganglioside was first acquired without peptide in 10 mM Hepes buffer (phosphate buffer was not used due its 31P signal), 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. After acquisition of the control spectrum without peptide, 20 μL of 0.3 mg/ml Aβ1-40 or 0.1 mg/ml MSI-78 was added into the same sample tube. Acquisition was then started after a 10 h incubation period to obtain the spectra of the LUVs in the presence of 0.5 wt % MSI-78 or 1.6 wt % Aβ1-40. Each spectrum is the result of 25,000 scans. Aβ1-40 was then allowed to incubate in LUVs for 4 days before 500 μM MnCl2 was added for the paramagnetic quenching measurements.

Results

Oligomerization of Aβ1-40 on the membrane strongly disrupts ganglioside-containing membranes

We estimated the degree of membrane disruption by Aβ1-40 by quantifying the dye leakage induced by Aβ1-40 from vesicle-encapsulated 6-carboxyfluorescein (24). Previous studies showed that freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 typically induces a very small amount of dye release for standard membrane compositions in comparison with other membrane-disrupting proteins, such as antimicrobial peptides (25,26). However, in those studies, membrane disruption was usually measured for only a few minutes after the addition of Aβ1-40, and therefore the time-dependent oligomerization of the Aβ1-40 peptide was not taken into account (25–27).

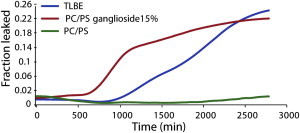

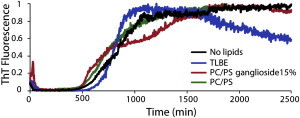

To take into account how the ongoing aggregation of Aβ1-40 may affect membrane disruption, we recorded dye leakage from model membranes over several days after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 (Fig. 1). Corresponding assays using the amyloid-sensitive dye ThT were performed to measure fiber formation (Fig. 2). No significant leakage was observed from membranes composed of only POPC/POPS within 2 days, suggesting that Aβ1-40 does not cause membrane defects that allow the passage of 6-carboxyfluorescein in POPC/POPS membranes. However, membrane binding by Aβ1-40 is highly sensitive to membrane composition (28,29). To test a more physiologically relevant membrane composition, we performed the identical experiment with lipid vesicles formed from TLBE, which provided strikingly different results. Leakage from TLBE vesicles was initially low, in similarity to the leakage observed from POPC/POPS vesicles. However, leakage from TLBE vesicles sharply increased after a lag time of ∼1000 min after the addition of Aβ1-40. The timescale of release shares the same sigmoidal profile as amyloid formation (Fig. 2), suggesting that this second phase of membrane disruption is correlated with fiber formation. However, an exact correspondence cannot be made, because the ThT assay measures fiber formation both in solution and on the membrane, whereas the dye leakage assay reflects only fiber formation on the membrane, and thus the two assays have different sensitivities (Fig. S1). To establish correspondence between 6-carboxyfluorescein leakage and fiber formation, we performed a seeded fiber growth assay in the presence of TLBE LUVs (Fig. S2) (30). Neither preformed fibers nor freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 caused dye leakage; however, leakage was immediately apparent after freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 was added to the preformed fibers, establishing a direct leakage between fiber growth and membrane disruption.

Figure 1.

Membrane disruption induced by Aβ1-40, as measured by the 6-carboxyfluorescein dye leakage assay. The graph illustrates the release of 6-carboxyfluorescein induced by 10 μM Aβ1-40 from 0.2 mg/ml POPC/POPS LUVs 7:3 (green line), 0.2 mg/ml POPC/POPS/ganglioside LUVs 5.5/3/1.5 (red line), and 0.2 mg/ml TLBE LUVs (blue line). Dye leakage occurs only after a lag period and is detected only in ganglioside-containing membranes. Experiments were performed at room temperature in 10 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Results are the average of three measurements.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of Aβ1-40 amyloid formation measured by ThT fluorescent emission. The graph shows 10 μM Aβ1-40 in buffer in the absence of membranes (black line) and in the presence of 0.2 mg/ml POPC/POPS 7:3 LUVs (green line), 0.2 mg/ml POPC/POPS/ganglioside 5.5/3/1.5 LUVs (red line), and 0.2 mg/ml TLBE LUVs (blue line). Experiments were performed at room temperature in 10 mM phosphate buffer, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Results are the average of three measurements.

The dye release assay showed that Aβ1-40 disrupts TBLE vesicles substantially more efficiently than it disrupts PC/PS vesicles. TLBE is a mixture of a variety of phospholipids, cholesterol, sphingolipids, and gangliosides. Gangliosides in particular may be important for membrane disruption, as several studies have shown that Aβ binding to the membrane surface is strongly enhanced by the ganglioside content (23,25,31,32).

To test whether the presence of ganglioside contributed to membrane disruption by oligomeric Aβ1-40, we performed the same dye leakage experiment using a simpler model membrane system (5.5:3:1.5 molar ratio of POPC/POPS/total ganglioside extract) containing an amount of ganglioside similar to that found in the TLBE (33). The results for this sample resemble those obtained from TLBE (Fig. 1, red line), confirming that the presence of ganglioside in the membrane is sufficient to induce membrane defects that allow the passage of 6-carboxyfluorescein.

Cation-selective pores form immediately upon addition of Aβ to all membrane types

The results of the carboxyfluorescein assay suggest that the level of membrane disruption after addition of Aβ1-40 is initially low but becomes higher after oligomerization begins. Although this finding is consistent with the well-known toxicity of protofibrillar Aβ, many conductance studies in planar lipid bilayers have shown channel-like activity occurring immediately after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 (11,34–37), well before the appearance of fibers. In addition, the pores detected by electrical recording are cation-selective (but 6-carboxyfluorescein is negatively charged) and are predicted on the basis of AFM measurements to have an inner diameter of 2 nm, which may be too small to allow efficient passage of the 6-carboxyfluorescein molecule (7). This raises the possibility that Aβ1-40 quickly forms pores in the membrane, but the pores are not detected by the 6-carboxyfluorescein dye leakage assay due to its large size or the negative charge of the molecule.

To test this possibility, we measured the influx of Ca+2 ions into the LUV using vesicle-encapsulated, calcium-sensitive Fura-2 dye. Calcium ions are smaller than 6-carboxyfluorescein (the Stokes radius of the hydrated Ca+2 ion is 0.3 nm, compared with 0.7 nm for fluorescein) (38,39) and positively charged, and therefore measurements of Ca+2 influx correspond more directly to conductance measurements on planar lipid bilayers. (In principle, the assay does not distinguish between Ca+2 influx and Fura-2 efflux; however, the smaller size of Ca+2 relative to Fura-2 (molecular weight 636.5) and its positive charge make Ca+2 influx more likely.).

Fig. 3 shows the Ca+2 influx obtained 30 min after incubation with Aβ1-40. Influx of Ca+2 occurs shortly after the addition of the peptide (within 10 min), well before membrane disruption as measured by the 6-carboxyfluorescein measurement (Fig. 1), and fiber formation as measured by ThT fluorescence (Fig. 2). The measurements in Fig. 3 were obtained by allowing Aβ1-40 to bind to membrane for a short incubation period (10 min) before the addition of Ca+2, because Ca+2 may affect the affinity of Aβ1-40 for the membrane (41). To better estimate the kinetics, we performed additional experiments in TLBE LUVs by simultaneously adding Ca+2 and Aβ1-40 to the membrane (Fig. S3). Ca+2 influx was immediately detected in these experiments; however, the total amount was lower, probably due to the reduced affinity of Aβ1-40 for Ca+2 containing membranes (41). The amount of influx induced by Aβ1-40 in TLBE vesicles is significant, but less than that induced by the strongly membrane-disruptive antimicrobial peptide MSI-78 (also known as pexiganan), which completely disrupts the membrane at equivalent concentrations (Fig. 3) (42). Interestingly, we detected Ca+2 influx in POPC/POPS LUVs, which do not contain ganglioside (Fig. 3, light gray bars), although the amount was less than that observed for the TLBE LUVs. This finding is in contrast to the 6-carboxyfluorescein assay, in which membrane disruption of POPC/POPS LUVs was negligible even after prolonged incubation. The small but measurable Ca+2 influx in POPC/POPS LUVs suggests that the presence of ganglioside enhances the formation of cation-selective small pores by the peptide, but is not absolutely essential for their formation.

Figure 3.

Ca+2 influx into LUVs after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40. The maximum values of Ca+2 ion influx detected by encapsulated Fura-2 after 30 min of incubation with freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 from 0.2 mg/ml TLBE LUVs (dark gray bars) or 0.2 mg/ml POPC/POPS 7:3 LUVs (light gray bars) are shown. In contrast to the 6-carboxyfluorescein dye release assay, Ca+2 influx occurs shortly after the addition of Aβ1-40 and occurs weakly in the absence of gangliosides. The antimicrobial peptide MSI-78 was used as a reference for total disruption of the membrane (black bar).

Zinc ions can block early permeabilization by pores, but not fiber-dependent membrane disruption

To confirm that Ca+2 influx is correlated with the formation of small pores similar to those detected by electrical recording in planar bilayers, we repeated the experiment with Fura-2 using Zn+2 ions instead of Ca+2. The ability of Zn2+ to block the activity of the Aβ1-40 peptide channel in single-channel conductance measurements is well established (10,43–46) and is believed to result from the specific binding of Zn+2 to His-13 and His-14 in the interior of the channel (47). Accordingly, Zn+2 is not expected to penetrate into LUVs if the pores detected by the Fura-2 assay are similar to those detected by single-channel recording.

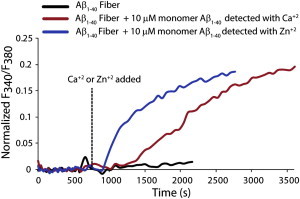

Fig. 4 shows a comparison of the results obtained with the Fura-2 assay using Ca+2 ions (red line) and Zn+2 ions (blue line). Although we clearly observed influx of Ca+2 inside the LUV immediately after the addition of Aβ1-40, we did not observe any influx of Zn+2. Because Fura-2 binds Zn+2 more tightly than it binds Ca+2 (48), and MSI-78 permits the influx of both Ca+2 and Zn+2 (Fig. S4), this result indicates that Zn+2, unlike Ca+2, is unable to penetrate into the interior LUV containing Aβ1-40, even though the two ions are similar in charge and size. This finding suggests that the first step of membrane disruption involves the formation of small-sized pores similar to those detected by single-channel electrical recording.

Figure 4.

Zn2+ inhibits the pore activity of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40. The graph shows the influx of Ca+2 (red line) and Zn2+ (blue line) ions induced by Aβ1-40 on 0.2 mg/ml TLBE LUVs. Freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 was added to each sample at time zero, and Ca+2 or Zn+2 was added at 600 s as indicated by the dashed line. Fura-2 is sensitive to both Ca+2 and Zn2+ ions, as indicated by the control membrane disruptive MSI-78 peptide (Fig. S4).

As mentioned above, membrane disruption is initially selective for Ca+2 over carboxyfluorescein but becomes nonselective as time progresses (compare Figs. 1 and 3). This finding implies that two distinct mechanisms are operational in membrane disruption by Aβ1-40. To verify that the mechanism underlying the second step of membrane disruption is different from the initial pore formation, and to demonstrate that it involves fiber growth on the surface of the bilayer, we measured the influx of ions into the LUV caused by fiber elongation by adding freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 to the solution after incubating the model membrane with preformed fibers. As expected, the mature preformed fibers, which do not disrupt membranes (23), did not induce the influx of Ca+2 into TLBE LUVs (Fig. 5, black line) by themselves. However, once fiber elongation was initiated by adding freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 to the preformed Aβ1-40 fibers, the LUVs became permeable to both Ca+2 and Zn+2. This finding indicates that the elongation of the amyloid fibers on the membrane surface disrupts membranes by a mechanism different from that initially observed when freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 was added to the membrane, because the defects in the membrane caused by fiber elongation are permeable to Zn+2.

Figure 5.

Zn2+ ions cannot block the fiber-dependent step of membrane disruption. The figure indicates the influx of Ca+2 (red line) and Zn2+ (blue line) ions induced by adding freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 to 0.2 mg/ml TLBE LUVs incubated with preformed fibers. Freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 was added to each sample at time zero, and Ca+2 or Zn+2 was added at 600 s as indicated by the dashed line. No Ca+2 influx was detected after the addition of preformed Aβ1-40 fibers (black line). The influx of both Ca+2 and Zn2+ ions (red and blue lines, respectively) were detected by seeding Aβ1-40 fiber formation with preformed fiber. This finding suggests that the fiber-dependent step of membrane disruption is not correlated with pore formation. LUVs were made from TLBE lipids.

Fiber-dependent membrane disruption occurs by a detergent-like mechanism

The Fura-2 assay did not allow us to determine how membrane disruption by fiber growth occurs. For other amyloidogenic peptides, it has been demonstrated that fiber growth is associated with the extraction of lipids from the membrane surface, resulting in the complete fragmentation of the membrane (49,50). Thus, it is possible that the fiber-dependent step of membrane disruption by Aβ1-40 involves a detergent-like mechanism characterized by the fragmentation of the membrane into peptide-lipid micelles or vesicles without the appearance of defined pores.

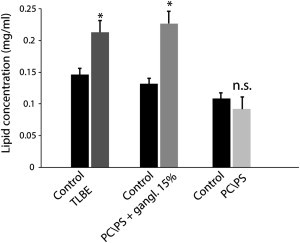

To test this hypothesis, we incubated LUV samples with Aβ1-40 for 2 days, centrifuged the samples to sediment intact LUVs, and then performed a Stewart assay to measure lipid concentrations in the supernatant (51). Fiber formation is expected to be complete within the 2-day incubation time (Fig. 2). For samples without Aβ1-40 (black bars in Fig. 6), only a small percentage of the total lipid concentration could be found in the supernatant, confirming that almost all of the lipids had pelleted after centrifugation, and lipids in the supernatant were likely to be the result of membrane fragmentation by Aβ1-40. Incubation with Aβ1-40 caused significant membrane fragmentation of ganglioside-containing membranes only (Fig. 6). For the POPC/POPS LUV samples (Fig. 6), the addition of Aβ1-40 did not elevate the soluble fraction of lipid, in agreement with the lack of carboxyfluorescein release from this sample (Fig. 1). This finding suggests that membrane disruption by fiber elongation may occur by a detergent-like mechanism. Moreover, it agrees with the results from the 6-carboxyfluorescein dye leakage assay, which show that membrane disruption occurs only when ganglioside is present in the membrane composition.

Figure 6.

Membrane fragmentation induced by prolonged incubation with Aβ1-40. Lipid concentrations in the supernatant after centrifugation from brain extract LUVs (dark gray bar) and POPC/POPS/gangliosides 5.5/3/1.5 LUVs (gray bar) after incubation with Aβ1-40 for 48 h are shown. The failure of lipid vesicles to sediment is an indication of their disruption to smaller micelle-like structures. No significant lipids were detected in the supernatant of samples containing POPC/POPS 7:3 (light gray bar), in agreement with the 6-carboxyfluorescein dye leakage assay (Fig. 1). Results are the average of three independent measures, and error bars represent the standard deviation.

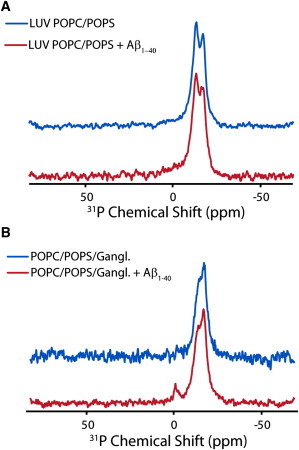

The formation of small, micelle-like lipidic structures that are characteristic of a detergent-like mechanism can also be detected with the use of 31P solid-state NMR (32,50). Fig. 7 shows the 31P spectra obtained for POPC/POPS and POPC/POPS/ganglioside LUVs before and after the addition of Aβ1-40. In each experiment, a 31P spectrum of the LUVs was collected before and after the addition of Aβ1-40. In the absence of Aβ1-40, both samples show resonances around −13 ppm and −17 ppm originating from PS-rich and PC-rich lipids, respectively, in the flat lamellar phases. An isotropic peak suggesting the formation of small, micelle-like lipidic structures appears after the addition of Aβ1-40 only in the sample containing ganglioside (Fig. 7 B). The corresponding POPC/POPS LUV sample does not show an isotropic peak (Fig. 7 A), matching the results of the sedimentation assay (Fig. 6).

Figure 7.

31P solid-state NMR of LUVs incubated with Aβ1-40. 31P chemical shift spectra of large unilamellar vesicles composed of 7:3 POPC/POPS (A) and 5.5:3:1.5 POPC/POPS/ganglioside (B) before (blue line) and after the addition of Aβ1-40 (red line) are illustrated. The small peak near 0 ppm in the ganglioside-containing spectra indicates the formation of small, rapidly tumbling lipid structures indicative of membrane fragmentation. The absence of a corresponding peak for samples without ganglioside is an indication that membrane fragmentation does not occur. All spectra were obtained at 37°C and referenced with respect to 85% H3PO4 at 0.0 ppm.

Paramagnetic quenching NMR experiments suggest that pores disappear after fiber formation

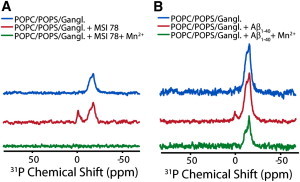

We employed paramagnetic quenching NMR experiments to test the integrity of the membrane after fiber formation was completed (52). Paramagnetic quenching experiments reveal the exposure of the lipid headgroup to solvent: if a lipid headgroup is exposed to paramagnetic Mn+2 ions, the corresponding 31P resonance will be broadened and the intensity will decrease due to paramagnetic enhanced relaxation. If the membrane is intact, only the 31P signal from lipids in the outer leaflet will be broadened, because the Mn2+ ions cannot penetrate into the LUV membrane to quench 31P signals from lipids in the inner leaflet. If pores or other defects are present that allow Mn+2 to pass through the lipid bilayer, both leaflets will be broadened to some degree. Interestingly, the intensity of the main resonance was reduced only by 50% after addition of Mn+2 to the sample incubated with Aβ1-40 for 4 days (Fig. 8 B), suggesting that only the headgroups of lipids in the outer leaflet of the bilayer are exposed to Mn+2 ions after prolonged incubation with Aβ1-40. The resonance corresponding to the isotropic phase was completely quenched, as expected for a micelle-like structure. By contrast, the intensity of the resonances corresponding to both the lamellar and isotropic phases decreased nearly 100% after addition of the pore-forming peptide MSI-78 (Fig. 8 A). The absence of the paramagnetic effect of Mn+2 on lipids in the inner leaflet of LUVs containing Aβ1-40 is an indication of the absence of pores or defects in the membrane after fiber formation.

Figure 8.

Absence of membrane defects after fiber formation as detected by paramagnetic quenching. (A and B) 31P chemical shift spectra of POPC/POPS/ganglioside LUVs before (top), after the addition of MSI-78 (A) and Aβ1-40 (B) (middle), and after the addition of 500 μM Mn+2 (bottom). Mn+2 completely quenches the peaks originating from both the isotropic and lamellar phases in the MSI-78 sample, but only partially quenches the lamellar phase in the Aβ1-40 sample, indicating the absence of membrane defects after fiber formation is complete. Aβ1-40 was allowed to incubate on the membrane for 4 days before acquisition. All spectra were collected at 37°C and referenced with respect to 85% H3PO4 at 0.0 ppm.

Discussion

Although it is widely accepted that disruption of the integrity of the plasma and perhaps the mitochondrial membranes contributes to the toxicity of amyloidogenic peptides, the mechanism underlying this process is still not completely understood. We demonstrate here that the membrane disruption caused by Aβ1-40 is a two-step process involving initial selective disruption of the membrane by pores followed by nonselective physical disruption during fiber formation. Both pore formation (11) and membrane fragmentation (20,21,32) have been observed in separate samples for Aβ1-40; however, the relationship between the two has not been established.

The initial step of membrane disruption by Aβ1-40 in LUVs shares many properties with the channels detected by single-channel recording. First, membrane disruption is detected in both cases very soon after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40. In LUVs, influx of Ca+2 occurs immediately after the addition of Aβ1-40 (Fig. 4). This compares favorably with single-channel recordings and live-cell calcium imaging studies that showed that the influx of Ca+2 can occur several minutes after the addition of Aβ1-40 (10,53). Second, both the channels observed in single-channel recordings and the pores initially observed in LUVs are charge selective (11). In LUVs, membrane disruption is initially characterized by the influx of positively charged Ca+2 (Figs. 3 and 4) but not the efflux of negatively charged 6-carboxyfluorescein into the LUV (Fig. 1), despite their relatively similar sizes. Finally, both the channel activity in supported lipid bilayers and the initial phase of membrane disruption in LUVs can be stopped by the addition of Zn+2 (Fig. 4), most likely through the interaction of Zn+2 with His-13 and His-14 located in the inner part of the channel (10,43–45,47). This finding suggests that pores of a specific structure are likely to be involved in both experiments.

The second phase of membrane disruption is distinguished by the leakage of 6-carboxyfluorescein from the vesicles. Initially, Aβ1-40 proteoliposomes of all membrane compositions are impermeant to 6-carboxyfluorescein (Fig. 1), and leakage can only be detected after a significant lag time in a manner reminiscent of fiber formation (Figs. 1 and 2). A direct link between fiber formation and membrane disruption is suggested by seeding experiments in which membrane disruption was immediately apparent after the addition of freshly dissolved Aβ1-40 to preformed fibers (Fig. 5).

Although early membrane disruption in LUVs appears to share many properties with the channels detected by single-channel recording, they both differ markedly from later membrane disruption in several ways. First, later membrane disruption is largely nonselective for the passage of molecules. Although both channels detected by electrical recording and the early phase of membrane disruption are selective for the passage of cationic molecules, the membrane becomes permeable to both negatively charged 6-carboxyfluorescein and Ca+2 as time progresses. The lack of selectivity in the second phase is consistent with a total loss of the physical integrity of the membrane, resulting in the appearance of small, micelle-like structures as time progresses (Figs. 6 and 7). Second, membrane damage by fiber elongation is not stopped by the addition of Zn+2 (Fig. 5). If anything, Zn+2 appears to enhance fiber-dependent membrane disruption (Fig. 5). Finally, the second phase is completely dependent on the presence of ganglioside. Whereas early pore formation is enhanced in ganglioside-containing membranes (Fig. 3), membrane fragmentation by fiber elongation cannot be observed at all in the absence of ganglioside (Figs. 6 and 7). All of these factors suggest that a second membrane-disrupting process is not detected in channel recording, most likely because breakage of the membrane correlates with the formation of large, membrane-bound Aβ1-40 oligomers (54). However, these findings are consistent with earlier 31P NMR and AFM results suggesting that Aβ1-40 leads to the eventual disintegration of membranes (21,32).

On the basis of our data, we cannot determine whether the two phases of membrane disruption are truly two separate and independent processes or a single process with several stages. Several researchers have noted that the pores formed by Aβ1-40 appear to be unstable. Instead, pores formed by Aβ1-40 appear to be dynamic, with subunits of the pore breaking off and coalescing into larger, extended, and ThT-positive aggregates (54,55). The formation of these larger aggregates is correlated with a large change in conductance that is in agreement with the start of a second phase of membrane disruption detected in our measurements (54). Furthermore, we show that membrane disruption by Aβ1-40 is transient and is abolished after fiber formation is complete (Fig. 8), suggesting the possibility that pores are converted into fibers during the membrane disruption process that eventually detach from the membrane. However, it is difficult to resolve this question using ensemble techniques that cannot follow individual oligomers on the membrane throughout the aggregation process.

Synthetic model membranes are advantageous because they simplify a complex system and allow hypotheses to be tested under controlled conditions. Although the model membranes used here are a simplification of the complex nature of biological membranes, our data could be useful for elucidating the mechanism underlying the toxicity of Aβ peptide to neurons. For example, it would be highly interesting to test the synergistic effects of channel-specific blockers such as the NA4 hexapeptide with inhibitors of fiber elongation in inhibiting Aβ (56). Experiments are under way to test this possibility.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (GM095640 to A.R.). D.K.L. was partly supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0087836).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Hardy J.A., Higgins G.A. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benilova I., Karran E., De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small D.H. Dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:1824–1829. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattson M.P., Cheng B., Rydel R.E. β-Amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollard H.B., Arispe N., Rojas E. Ion channel hypothesis for Alzheimer amyloid peptide neurotoxicity. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1995;15:513–526. doi: 10.1007/BF02071314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lal R., Lin H., Quist A.P. Amyloid β ion channel: 3D structure and relevance to amyloid channel paradigm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1966–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quist A., Doudevski I., Lal R. Amyloid ion channels: a common structural link for protein-misfolding disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10427–10432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502066102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demuro A., Parker I., Stutzmann G.E. Calcium signaling and amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:12463–12468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.080895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capone R., Jang H., Lal R. All-D-enantiomer of β-amyloid peptide forms ion channels in lipid bilayers. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1143–1152. doi: 10.1021/ct200885r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capone R., Quiroz F.G., Mayer M. Amyloid-β-induced ion flux in artificial lipid bilayers and neuronal cells: resolving a controversy. Neurotox. Res. 2009;16:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9033-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagan B.L., Thundimadathil J. Amyloid peptide pores and the β sheet conformation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;677:150–167. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6327-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arispe N., Rojas E., Pollard H.B. Alzheimer disease amyloid β protein forms calcium channels in bilayer membranes: blockade by tromethamine and aluminum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:567–571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz J.C., Simakova O., Pollard H.B. Small molecule blockers of the Alzheimer Aβ calcium channel potently protect neurons from Aβ cytotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3348–3353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813355106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirakura Y., Yiu W.W., Kagan B.L. Amyloid peptide channels: blockade by zinc and inhibition by Congo red (amyloid channel block) Amyloid. 2000;7:194–199. doi: 10.3109/13506120009146834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin H., Zhu Y.J., Lal R. Amyloid β protein (1-40) forms calcium-permeable, Zn2+-sensitive channel in reconstituted lipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11189–11196. doi: 10.1021/bi982997c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chimon S., Shaibat M.A., Ishii Y. Evidence of fibril-like β-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshi M., Sato M., Sato K. Spherical aggregates of β-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6370–6375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237107100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomonov I., Korkotian E., Sagi I. Zn2+-Aβ40 complexes form metastable quasi-spherical oligomers that are cytotoxic to cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20555–20564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morita M., Vestergaard M., Takagi M. Real-time observation of model membrane dynamics induced by Alzheimer’s amyloid β. Biophys. Chem. 2010;147:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michikawa M., Gong J.S., Yanagisawa K. A novel action of Alzheimer’s amyloid β-protein (Aβ): oligomeric Aβ promotes lipid release. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7226–7235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07226.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yip C.M., McLaurin J. Amyloid-β peptide assembly: a critical step in fibrillogenesis and membrane disruption. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1359–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda K., Yamaguchi T., Matsuzaki K. Mechanism of amyloid β-protein aggregation mediated by GM1 ganglioside clusters. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6433–6440. doi: 10.1021/bi200771m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams T.L., Johnson B.R.G., Serpell L.C. Aβ42 oligomers, but not fibrils, simultaneously bind to and cause damage to ganglioside-containing lipid membranes. Biochem. J. 2011;439:67–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brender J.R., Lee E.L., Gafni A. Biphasic effects of insulin on islet amyloid polypeptide membrane disruption. Biophys. J. 2011;100:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaurin J., Chakrabartty A. Membrane disruption by Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides mediated through specific binding to either phospholipids or gangliosides. Implications for neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26482–26489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong P.T., Schauerte J.A., Gafni A. Amyloid-β membrane binding and permeabilization are distinct processes influenced separately by membrane charge and fluidity. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;386:81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gauci A.J., Caruana M., Vassallo N. Identification of polyphenolic compounds and black tea extract as potent inhibitors of lipid membrane destabilization by Aβ(42) aggregates. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:767–779. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki K. Physicochemical interactions of amyloid β-peptide with lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1935–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sani M.A., Gehman J.D., Separovic F. Lipid matrix plays a role in Aβ fibril kinetics and morphology. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel M.F., Khemtémourian L., Höppener J.W. Membrane damage by human islet amyloid polypeptide through fibril growth at the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda K., Matsuzaki K. Driving force of binding of amyloid β-protein to lipid bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;370:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakazawa Y., Suzuki Y., Asakura T. The interaction of amyloid Aβ (1-40) with lipid bilayers and ganglioside as studied by 31P solid-state NMR. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2009;158:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen M., Nerdal W. Anticancer cisplatin interactions with bilayers of total lipid extract from pig brain: A13C, 31P and 15N solid-state NMR study. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008;34:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue S. In situ Aβ pores in AD brain are cylindrical assembly of Aβ protofilaments. Amyloid. 2008;15:223–233. doi: 10.1080/13506120802524858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang H., Arce F.T., Nussinov R. β-Barrel topology of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid ion channels. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;404:917–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kayed R., Pensalfini A., Glabe C. Annular protofibrils are a structurally and functionally distinct type of amyloid oligomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:4230–4237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808591200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Small D.H., Gasperini R., Foa L. The role of Aβ-induced calcium dysregulation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:225–233. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corti H.R., Frank G.A., Marconi M.C. An alternate solution of fluorescence recovery kinetics after spot-bleaching for measuring diffusion coefficients. 2. Diffusion of fluorescein in aqueous sucrose solutions. J. Solution Chem. 2008;37:1593–1608. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maroudas A., Weinberg P.D., Winlove C.P. The distributions and diffusivities of small ions in chondroitin sulphate, hyaluronate and some proteoglycan solutions. Biophys. Chem. 1988;32:257–270. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(88)87012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reference deleted in proof.

- 41.Meratan A.A., Ghasemi A., Nemat-Gorgani M. Membrane integrity and amyloid cytotoxicity: a model study involving mitochondria and lysozyme fibrillation products. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;409:826–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallock K.J., Lee D.K., Ramamoorthy A. MSI-78, an analogue of the magainin antimicrobial peptides, disrupts lipid bilayer structure via positive curvature strain. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3052–3060. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capone R., Jang H., Lal R. Probing structural features of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β pores in bilayers using site-specific amino acid substitutions. Biochemistry. 2012;51:776–785. doi: 10.1021/bi2017427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirakura Y., Lin M.C., Kagan B.L. Alzheimer amyloid aβ1-42 channels: effects of solvent, pH, and Congo Red. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;57:458–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arispe N., Pollard H.B., Rojas E. Zn2+ interaction with Alzheimer amyloid β protein calcium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1710–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawahara M., Arispe N., Rojas E. Alzheimer’s disease amyloid β-protein forms Zn(2+)-sensitive, cation-selective channels across excised membrane patches from hypothalamic neurons. Biophys. J. 1997;73:67–75. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Díaz J.C., Linnehan J., Arispe N. Histidines 13 and 14 in the Aβ sequence are targets for inhibition of Alzheimer’s disease Aβ ion channel and cytotoxicity. Biol. Res. 2006;39:447–460. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparr E., Engel M.F., Killian J.A. Islet amyloid polypeptide-induced membrane leakage involves uptake of lipids by forming amyloid fibers. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brender J.R., Dürr U.H.N., Ramamoorthy A. Membrane fragmentation by an amyloidogenic fragment of human islet amyloid polypeptide detected by solid-state NMR spectroscopy of membrane nanotubes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:2026–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart J.C.M. Colorimetric determination of phospholipids with ammonium ferrothiocyanate. Anal. Biochem. 1980;104:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Last N.B., Rhoades E., Miranker A.D. Islet amyloid polypeptide demonstrates a persistent capacity to disrupt membrane integrity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9460–9465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102356108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simakova O., Arispe N.J. Early and late cytotoxic effects of external application of the Alzheimer’s Aβ result from the initial formation and function of Aβ ion channels. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5907–5915. doi: 10.1021/bi060148g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schauerte J.A., Wong P.T., Gafni A. Simultaneous single-molecule fluorescence and conductivity studies reveal distinct classes of Aβ species on lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3031–3039. doi: 10.1021/bi901444w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang H., Arce F.T., Nussinov R. Misfolded amyloid ion channels present mobile β-sheet subunits in contrast to conventional ion channels. Biophys. J. 2009;97:3029–3037. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arispe N., Diaz J.C., Simakova O. Aβ ion channels. Prospects for treating Alzheimer’s disease with Aβ channel blockers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1952–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.