Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and many epithelial malignancies exhibit increased proliferation, invasion and inflammation, concomitant with aberrant nuclear activation of TP53 and NF-κB family members ΔNp63, c-REL and RELA. However, the mechanisms of crosstalk by which these transcription factors coordinate gene expression and the malignant phenotype remain elusive. Here we demonstrate thatΔNp63 regulates a cohort of genes involved in cell growth, survival, adhesion and inflammation, which substantially overlaps with the NF-κB transcriptome. ΔNp63 with c-REL and/or RELA are recruited to form novel binding complexes on p63 or NF-κB/REL sites of multiple target gene promoters. Overexpressed ΔNp63- or TNF-α-induced NF-κB and inflammatory cytokine IL-8 reporter activation depended upon RELA/c-REL regulatory binding sites. Depletion of RELA or ΔNp63 by siRNA significantly inhibited NF-κB-specific, or TNF-α-induced IL-8 reporter activation. ΔNp63 siRNA significantly inhibited proliferation, survival, and migration by HNSCC cells in vitro. Consistent with the above, an increase in nuclear ΔNp63 accompanied by increased proliferation (Ki67), and adhesion (β4 integrin) markers, and induced inflammatory cell infiltration was observed throughout HNSCC specimens, when compared to the basilar pattern of protein expression and minimal inflammation seen in non-malignant mucosa. Further, overexpression of ΔNp63α in squamous epithelia in transgenic mice leads to increased suprabasilar c-REL, Ki-67, and cytokine expression, together with epidermal hyperplasia and diffuse inflammation, similar to HNSCC. Our study reveals ΔNp63 as a master transcription factor that in coordination with NF-κB/RELs, orchestrates a broad gene program promoting epidermal hyperplasia, inflammation, and the malignant phenotype of HNSCC.

Keywords: Gene expression, inflammation, ΔNp63, NF-κB, head and neck cancer

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) and other epithelia cancers display coordinated changes in cell proliferation, migration, and inflammatory cell infiltration, along with frequent abnormalities of the TP53 and NF-κB transcription factor families (1–5). HNSCC and epidermal malignancies are known to carry a high mutation rate for TP53, but TP53 mutation alone is insufficient to account for cancer development and differences in prognosis. This is attributable in part to the diversity of mutations or other mechanisms of inactivation that affect TP53 functions (6, 7). Additionally, more recent studies have pointed to redundant and distinct functions of other TP53 family members, such as p63, in modulation of gene expression and the malignant phenotype (8–10). p63 consists of six isoforms differing in the N or C-terminus as a result of alternative promoter usage or splicing (11). The TAp63 isoforms contain full-length N-terminal transactivating domains, while ΔNp63 has a truncated N-terminus. The p63 isoforms share high sequence homology with the TP53 DNA binding domain (12), enabling TA and ΔNp63 isoforms to transactivate or inhibit TP53 target genes, respectively. ΔNp63 is the most abundant isoform detected in the basal layer of mucosa, skin, and other epithelia (8, 13), and in HNSCC (14). p63 isoforms also regulate a broad range of target genes (13, 15, 16), although the different partners and mechanisms by which they coordinate such gene activation remains incompletely defined.

Recently, we demonstrated that ΔNp63 can form a novel complex with the transcriptionally functional NF-κB family member c-Rel to bind a p63 regulatory site and repress expression of p21Cip1, thus enhancing proliferation of murine keratinocytes (17). The NF-κB/REL family includes five functionally and structurally related proteins, including RELA and c-REL, which are often classified together as components of the canonical NF-κB pathway (18). Aberrant activation of RELA is also observed in the majority of HNSCC and many malignancies, and shown to regulate a broad gene program to promote cancer progression, inflammation, metastasis, and resistance to therapies (1, 4, 19). However, RELA, c-REL, and other NF-κB family members and transcription factors were found to be variably activated and sensitive to proteasome inhibition in different subsets of HNSCC lines and specimens from patients resistant to therapy (20, 21). These findings suggested that c-REL, RELA, and other transcription factors might contribute to co-regulation of NF-κB target gene expression and the malignant phenotype in HNSCC and epidermal tumorigenesis.

The finding that ΔNp63 and c-Rel can bind and down-regulate a classical TP53 target gene suggested a new paradigm by which these two transcription factors can interact and co-regulate target gene (s). In the present study, we explored the hypothesis that ΔNp63, RELA and c-REL members of the NF-κB family can interact together to more broadly regulate transcription of TP53/p63 and REL/NF-κB target genes known to be important in pathologic alterations in HNSCC and squamous epithelia.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

The UM-SCC lines used were originally obtained from Dr. Thomas E. Carey, University of Michigan in 2000. TP53 sequence analysis for exons 4–9 was performed in our laboratory as reported (22). DNA was sent for sequence genotyping in 2008 and fall 2010 to compare and verify their unique origin from original stocks, as recently described (23). Nine loci analyzed included D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D8S1179, D13S317, D18S51, D21S11, FGA, vWA, and amelogenin. Primary human epidermal keratinocytes (HEKA) were purchased and cultured following manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen), and used within five passages. HEKA and human oral mucosa keratinocytes (HOK) exhibit similar global gene expression patterns for ΔNp63 and other genes presented in this study (data not shown).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Frozen HNSCC tissues were from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. Detailed IHC protocol is presented in the supplemental information. The staining and morphology were observed under Olympus BX51 microscope, and images were captured by Olympus DP70 camera and DP70 Image Manager software. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded HNSCC and mucosal tissue arrays were from Cybrdi (Rockville, MD). Images were acquired using an Aperio Scanscope, and the staining intensity was quantified using the Aperio Cell Quantification Software (Aperio, Vista, CA).

siRNA

The siRNA targeting the unique exon in the N-terminal of ΔNp63 was made by Integrated DNA Technologies (Supplementary Table S1), based on the previous publication (24). siRNAs targeting TAp63, total p63 or other genes were purchased from Dharmacon or Qiagen.

Real time RT-PCR

RNA isolated was subjected to reverse transcription and PCR as described (25). PCR primers for ΔNp63 and TAp63 were synthesized (Supplementary Table S1), and other primers were purchased (Applied Biosystems). The gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA as an internal control.

Reporter gene assays

Reporter gene activities were assayed using Dual-Light System kit (Applied Biosystems), and measured by Wallac VICTOR2 1420 Multilabel Counter (Perkin Elmer). Differences in reporter activity due to nonspecific transfection or gene related antiproliferative or cytotoxic effects, were normalized using either β-Gal or WST1 following the manufacturer’s suggestion (Roche Diagnostics).

Prediction of transcription binding sites

The binding sites in the promoter regions of NF-κB, p63, or TP53 target genes were identified using the published binding and experimental information after query of NCBI and other databases. The novel p63 and NF-κB binding sites were predicted using Genomatix sofware (Munchen, Germany) and position weight matrices (PWM) built on published information (see Supplemental Methods).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay (ChIP)

Protein-DNA complexes were precipitated using antibodies indicated and PCR was performed using specific primers as described in Supplemental Methods.

Images of cultured cell morphology, wound healing and cell migration through Matrigel

Images of cultured cells and wound healing experiments were taking under Olympus IX70 inverted microscope at room temperature using the SPOT RT color digital camera (Diagnostic Instrument, Inc), and software of SPOT Advanced version 4.0.1. The images of cells migrating through Matrigel were acquired using an Aperio Scanscope, and the quantification was performed using the Aperio Cell Quantification Software (Aperio, Vista, CA).

ΔNp63α transgenic (TG) mouse model and immunofluorescence

A Tet-responsive ΔNp63α transgenic mouse model has been developed by crossing HA-ΔNp63α with tet-OFF transgenic animals under bovine K5 promoter (K5-tTA) (26). Expression of ΔNp63α in TG mouse was induced after birth, and immunofluorescence staining was performed as described in Supplemental Methods. Immunofluorescence images were observed under a Nikon FXA fluorescence microscope, captured using a Nikon digital camera, and analyzed using ImageJ, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator software.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the statistical analysis relative to the control is calculated (t-test, * p<0.05).

Results

ΔNp63 regulates a broad gene program that overlaps with NF-κB targets

Nuclear ΔNp63 staining of intermediate and strong intensity was observed throughout malignant epithelia in 18/21(~85%) frozen HNSCC specimens when compared with the basilar localized staining pattern seen in squamous mucosa (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Proliferating human keratinocytes (HEKA) and HNSCC (UM-SCC) lines predominantly expressed ΔNp63 mRNA and protein, with most HNSCC lines with mutant (mt)TP53 expressing higher levels than those with wild-type (wt)TP53 (Supplementary Fig. S1B). To investigate the broad role of ΔNp63 in regulating gene expression, we selected UM-SCC1 and UM-SCC6 lines with wtTP53 and intermediate ΔNp63 expression, as well as UM-SCC22B and UM-SCC38 lines with mtTP53 and higher ΔNp63 expression (Supplementary Fig. S1B). p63 was knocked down by specific siRNA targeting ΔNp63, total p63 (Supplementary Fig. S2A, Supplementary Table S1), or TAp63 (not shown), confirming distinctive specificity of ΔNp63 knockdown. A broad gene panel, including NF-κB and TP53 family targets, was tested (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. S2B, Supplementary Table S2). In UM-SCC1 cells, ΔNp63 knockdown led to significant modulation of genes critical in inflammation, including IL-1 family members, CSF2, IL6, and IL8; in growth regulation and apoptosis, such as PDGFA, TGFα, TP53, p73, MDM2, BCL-2 and BCL-xL; and in adhesion, such as ITGA6, ITGB4 and ICAM1 (Fig. 1A). Similar results were obtained for most genes in UM-SCC6, UM-SCC22B, and UM-SCC38 cells, although some differed between wt and mtTP53 lines (Supplementary Fig. S2B, Supplementary Table S2). Together, these results suggested that ΔNp63 could co-regulate a broad gene program, including NF-κB as well as TP53 target genes.

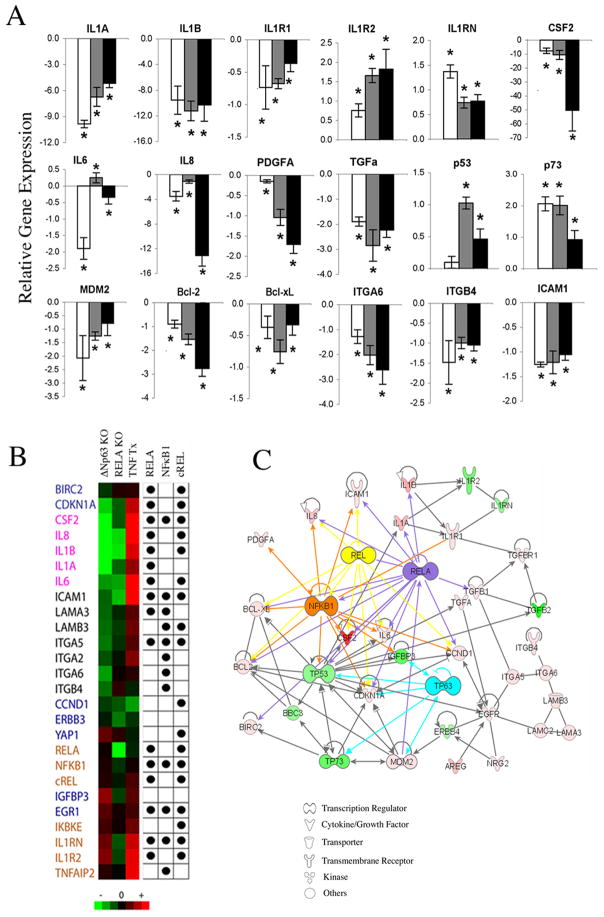

Figure 1. Knockdown of ΔNp63 regulates a broad gene expression program that overlaps with the NF-κB transcriptome and network.

A, Relative fold-change in mRNA expression after ΔNp63 siRNA transfection of UM-SCC 1 for 24, 48 or 72 hrs (white, grey, black bars); *p<0.05 vs. control siRNA. B, Heat map for up- (red) or down-regulated (green) mRNA expression after ΔNp63, RELA siRNA or TNF-α treatment. Dots indicate predicted RELA, NF-κB1 and c-REL binding sites in the proximal promoter regions (−500bp ~ +100bp of TSS). Gene categories are: Blue, growth and apoptosis; pink, cytokines; black, adhesion; brown, NF-κB. C, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) illustrates important functional networks between ΔNp63-modulated genes and RELA, c-REL or NFκB1.

Systems biology analyses predict transcription binding motifs and network between ΔNp63 and NF-κB regulated genes

Next, we compared 80 genes modulated by ΔNp63 or RELA knockdown, or treatment with NF-κB inducer TNF-α, and found broad overlap of 26 genes (Fig. 1B). We then predicted NF-κB binding motifs on the proximal promoters (−500bp ~ +100bp) of these genes using Genomatix software and position weighted matrices (PWMs) based on published data (Bin Yan, unpublished, Supplementary Methods). RELA and c-REL sites were highly represented in the proinflammatory cytokine and NF-κB gene clusters; while NF-κ1 sites predominated in the adhesion gene cluster (Fig. 1B). Literature review and annotated Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) linked many of the modulated genes via related physical, signal or transcriptional interactions to ΔNp63 and NF-κB (Fig. 1C), or other pathways (Supplementary Table S3). These findings supported the hypothesis that ΔNp63 regulates a broad gene program that partially overlaps with the NF-κB transcriptome.

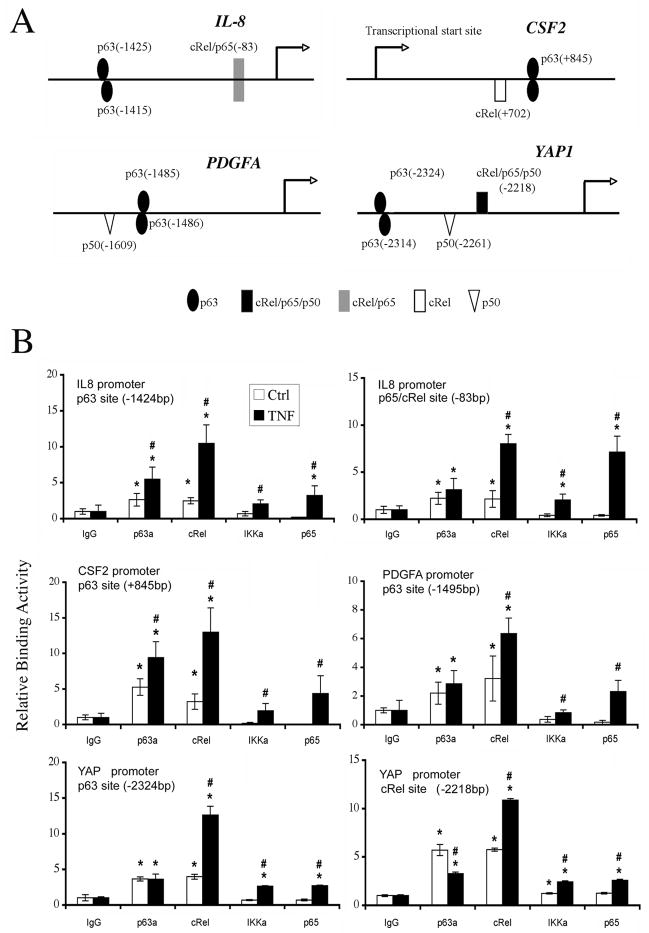

ΔNp63, c-REL and RELA binding to predicted sites of target gene promoters detected by ChIP

We searched for putative p63 and/or NF-κB-specific regulatory sequences in the promoter regions of p63 target genes identified in this study using Genomatix (Bin Yan, unpublished, Supplementary Methods). Many of ΔNp63 target genes contained predicted p63 and/or NF-κB binding sites (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S4), consistent with co-regulation and a potential functional interaction between the two factors (Fig. 1B, 1C; Supplementary Table S3). To test this, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP) were performed in cell lines that express ΔNp63 at relatively high (UM-SCC46, Fig. 2B) or lower levels (UM-SCC1, not shown). We detected significant basal p63 binding activity on 13 sites of 8 promoters, including a known p63 binding site in the p21Cip1 gene, which served as a positive control (Supplementary Table S4) (17, 27). IL-8, CSF2, PDGFA, and YAP1 promoters were further selected for ChIP analyses with multiple antibodies, without or with TNF-α treatment (Fig. 2B). Antibodies included for ChIP were based on previous findings that in HNSCC ΔNp63 can form a protein complex with c-REL (17); canonical RELA/p65 is often activated (18, 28); and IKKα may bind to ΔNp63 (13, 29). ChIP results revealed that p63 and c-REL exhibited higher basal binding activities at most predicted binding sites, and TNF-α potently induced c-REL binding to all sites. As expected, TNF-α also greatly induced RELA/p65 binding activity in the previously defined proximal p65/cREL site in IL-8 promoter (30). Minimal basal and TNF-α-induced IKKα binding activities were detected (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Distinct ΔNp63, cREL and RELA binding activities on p63 or NF-κB responsive elements.

A, p63 and NF-κB/REL binding sites (with base pairs from transcription start site) on gene promoters were predicted by Genomatix by including user-defined p63 PWM as described in Supplemental Methods. B, ChIP assay performed using anti-p63, c-REL, IKKα, RELA and isotype antibodies without (Ctrl) or with TNF-α treatment, followed by real-time PCR. Mean Relative binding activity +/−SD for triplicates; p<0.05 compared with isotype (*), or between Ctrl and TNF-α treatment (#).

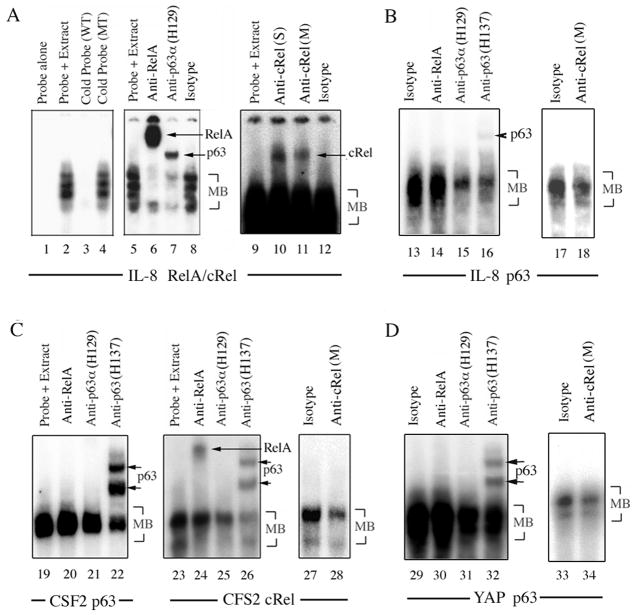

Coordinate binding of p63, c-REL and/or RELA protein complexes to p63 and NF-κB regulatory elements

To investigate if ΔNp63, c-REL and RELA bind to the same cognate elements present in these promoters, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed with nuclear extracts from UM-SCC1 (Fig. 3) and UM-SCC46 (not shown). The IL-8 promoter RELA/c-REL site oligonucleotide bound multiple complexes (main bands: MB, Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4). Remarkably, supershift with an anti-RELA antibody (lane 6), or an antibody against the p63 C-terminus (H129, lane 7), attenuated most MBs. Lesser supershift of MB activity was also detectable using two different c-REL C-terminal antibodies (lanes 10, 11). A predicted IL-8 promoter p63 site oligonucleotide bound a complex was attenuated by both p63-specific antibodies (Fig. 3B, lanes 15, 16) and shifted with anti-p63 H137 antibody (lane 16). While RELA antibody had no significant effect (lane 14), c-REL antibody attenuated MB binding activity, indicative of c-REL co-binding to the predicted p63 binding site (lane 18). A predicted CSF2 promoter p63 site oligonucleotide bound complex was shifted or attenuated with anti-p63 antibodies, but not with RELA antibody (Fig. 3C, lanes 20–22). For the predicted CSF2 promoter REL site, RELA and p63 were both detected by supershift (lanes 24–26), and anti-c-REL antibody also significantly decreased the MBs (lanes 27, 28). We obtained similar results for the YAP promoter p63 site (Fig. 3D). Both anti-p63 antibodies attenuated MBs (lane 31, 32), with H137 detecting two supershifted bands (lane 32). While no supershift was detected with anti-RELA (lane 30), anti-c-REL attenuated MB binding activity (lane 34). These data provide evidence for coordinate and differential binding of distinct p63, c-REL and/or RELA complexes to p63 and REL/NF-κB regulatory elements of multiple genes.

Figure 3. Coordinate binding of p63, c-REL and/or RELA protein complexes to p63 and NF-κB regulatory elements.

EMSA using nuclear extract from UM-SCC1 treated with TNF-α, incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes for A, known IL-8 promoter RELA/cREL (−83bp, lane 1–12), and B, predicted p63 (−1425bp, lane 13–18) sites; C, CSF2 promoter p63 (+845bp, lane 19–22) or c-REL (+702bp, lane 23–28) sites; and D, a YAP promoter p63 site (−2324bp, lane 29–34). Experimental conditions include labeled probe alone; labeled probes plus nuclear extracts; labeled probe and nuclear extract plus 50-fold excess unlabeled wild-type (WT) or mutant (MT) competitor DNA; anti-RELA, anti-p63 (H129 or H137), anti-c-REL (S: Santa Cruz; M: Millipore), or isotype control antibodies. MB: main band.

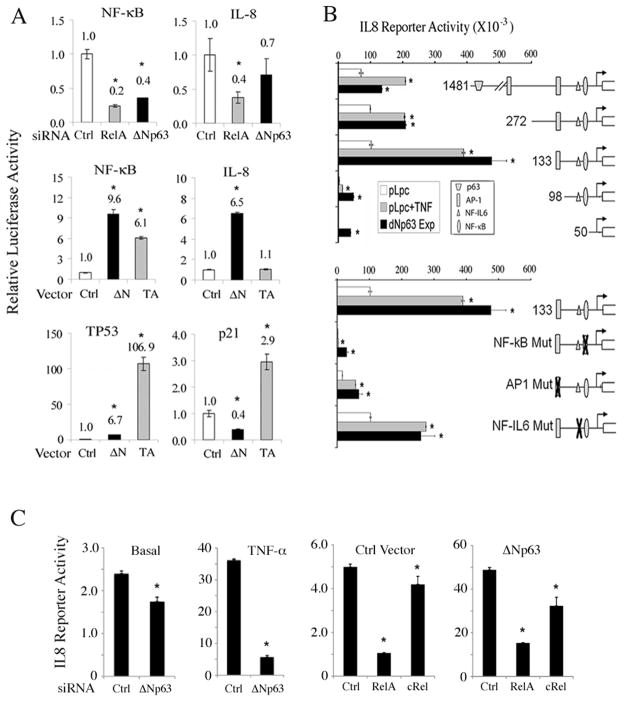

p63 and TNF-α regulate NF-κB, TP53, p21Cip1 or IL-8 transcription activity

Next we investigated how p63 modulated NF-κB or TP53 mediated transcriptional activity (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S3). ΔNp63 knockdown markedly decreased specific NF-κB or RELA/c-REL site-dependent IL-8 reporter gene activities (−133bp construct) (30), although the effects were less potent than with RELA knockdown (Fig. 4A, upper row). Conversely, overexpression of 3Np63 increased NF-κB and IL-8 reporter gene activities more potently than TAp63 (Fig. 4A, middle row), at a level similar to classical NF-κB inducer, TNF-α (Supplementary Fig. S3, left column). In contrast, overexpressed ΔNp63 weakly stimulated TP53, while repressing TP53 target p21Cip1 reporter activity (Fig. 4A, bottom row).

Figure 4. ΔNp63 and TNF-α modulate NF-κB, IL-8, TP53 and p21 reporter activities.

A, Relative NF-κB-specific, NF-κB-dependent IL-8 (−133bp), TP53-specific and TP53-dependent p21Cip1 luciferse reporter activities 48 hours after transfection of UM-SCC1 with Ctrl, RELA or Δ Np63 siRNAs, or overexpression of Ctrl, ΔNp63α or TAp63α vectors, as indicated. Normalized with β-gal. *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl. B, Relative IL-8 luciferase reporter activity for serially deleted or binding site-specific point mutant promoter constructs, which include p63, NF-κB, AP-1, and NF-IL6 binding sites. UM-SCC1 cells were transfected with indicated reporter constructs plus Ctrl (pLpc), TNF-α (20ng/ml), or ΔNp63α expression vectors. Mean+SD of reporter activities of 6 replicates, adjusted for cell density by WST1 48 hrs after transfection. *p<0.05 vs. baseline. C, IL-8 promoter (−133bp) reporter activity; Left panels, Basal (without) or with TNF-α for 24 hours preceded by Ctrl or ΔNp63 siRNA for 46 hours. Right panels, co-transfected with Ctrl or ΔNp63 expression vector, and Ctrl, RELA or c-RELs siRNAs for 70 hours. Mean+SD for four replicates, after normalization for cell density by WST1. *p<0.05 vs. ctrl.

Transcriptional regulation of the IL-8 gene by ΔNp63 was further examined in UM-SCC1 cells using luciferase reporter constructs with serial deletions and point mutations (Fig. 4B) (30). Consistent with observations above, overexpression of ΔNp63 exhibited a similar stimulatory pattern for most of the promoter constructs as that of NF-κB-inducing cytokine TNF-α. Deleting the distal predicted p63 binding site (−1424bp) had a minimal effect, while increased reporter activity was observed using the minimal −133bp promoter construct containing the RELA/c-REL binding site, for which we established p63, c-REL and RELA co-binding activities above (Fig. 3A, lane 5–12). Further, deletion or point mutation of this RELA/c-REL site (−83) or nearby AP-1 site (−128bp) had profound impact on both TNF-α and ΔNp63-induced reporter activity (Fig. 4B, lower panel), indicating that ΔNp63 and TNF-α induced IL-8 activation are both dependent on these sites.

To further test the dependency of IL-8 promoter activity on ΔNp63, RELA or c-REL transcriptional components, IL-8 reporter activity was measured under combinatory knockdown or inducing conditions (Fig. 4C). ΔNp63 depletion partially inhibited basal IL-8 reporter activity, and nearly completely suppressed TNF-α-induced IL-8 reporter activation (left two panels). Conversely, basal level (control vector) IL-8 reporter activity was more strongly suppressed by depletion of RELA than c-REL, whereas ΔNp63 overexpression enhanced the relative contribution of c-REL (right two panels). These results are consistent with the relatively greater binding of RELA and ΔNp63 relative to c-REL to the IL-8 RELA/c-REL binding site as demonstrated by EMSA (Fig. 3A), and previous evidence indicating RELA is the major NF-κB family subunit responsible for binding and transactivation of the IL-8 promoter in HNSCC (28).

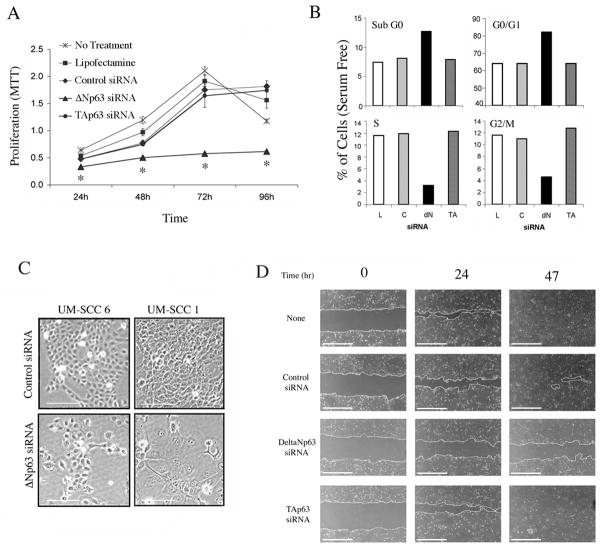

ΔNp63 modulates proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, survival and migration in HNSCC cell lines

Knockdown of ΔNp63, but not TAp63, markedly inhibited cell proliferation, increased sub-G0 DNA fragmentation and G0/G1 blockade, and decreased S and G2/M cell cycle phases in UM-SCC1 and UM-SCC6 lines (Fig. 5A and B, Supplementary Fig. S4A and B). ΔNp63 depletion also induced larger and flatter cells of differentiated cell morphology (Fig. 5C), reduced wound healing motility in scratch assay (Fig. 5D and Supplemental Fig. S4C), and cell migration in classical Matrigel assay by 35% (p<0.05; Supplementary Fig. S4D). Thus the effect of modulation of ΔNp63 upon multiple vital biological functions is consistent with its role in the regulation of a broad gene program.

Figure 5. ΔNp63 regulates HNSCC proliferation, cell cycle, differentiation and migration.

UM-SCC1 cells were transfected with lipofectamine (L), control (C), ΔNp63 or TAp63 siRNA as indicated. A, Cell proliferation measured by MTT assay. *p<0.05 vs control. B, DNA cell cycle distribution (G0/G1-S-G2/M) at 48 hrs and DNA fragmentation (sub G0) measured at 72hrs by flow cytometry. C, Photomicrographs of cell morphology after 96 hours (100X, scale bar: 100μm). D, Wound assay, UM-SCC1 monolayers were scratched 24 hrs after indicated transfections, and wound closure was photographed and measured at indicated time points (40X, scale bar: 1000μm).

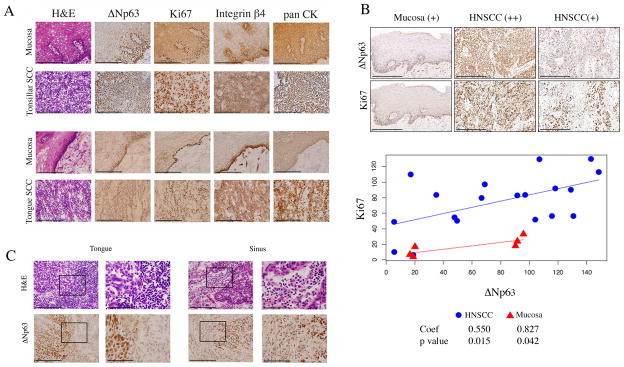

Increase in ΔNp63, Ki67, and integrin β4 immunostaining and inflammation in HNSCC compared with mucosa

We further examined the pattern of expression of ΔNp63, markers of proliferation (Ki67) and adhesion (β4 integrin), and cellular inflammation in human HNSCC and mucosa specimens. An increase in nuclear localized ΔNp63 staining was observed throughout the malignant epithelia in most HNSCC samples from independent series of 21 frozen (e.g. Fig. 6A, Supplemental Fig. S1) and 20 fixed tumor tissues (e.g. Fig. 6B). In contrast, nuclear ΔNp63 was predominantly localized in the basal layers of 2 patient-matched mucosa available from the series of frozen tissues (Fig. 6A, Supplemental Fig. S1), and 6 mucosas from the series of fixed tissues (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, we observed a similar pattern of staining for the Ki67 proliferative marker, and β4 integrin adhesion marker thoughout HNSCC tumor specimens, and basilar pattern of expression for these markers in mucosa (Fig. 6A). We found a positive and statistically significant correlation between ΔNp63 and Ki67 IHC histoscores for 19/20 (95%) HNSCC and 6 mucosa tissues from the tissue array (Fig. 6B). One outlier among the HNSCC samples exhibited higher Ki67 staining but low ΔNp63 IHC staining, possibly related to a different mechanism of Ki67 protein expression. Among three mucosa samples with relatively higher ΔNp63 andintermediate Ki67 staining, epithelial hyperplasia with expansion of basilar nuclear layers was observed (e.g, Fig. 6A, upper vs. lower panel of mucosa). Additionally, increased nuclear ΔNp63 in HNSCC was accompanied by adjacent focal or diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells in 9/20 specimens (45%, p=0.04, Fisher exact test, not shown). Thus, the ability of ΔNp63 to broadly regulate gene expression and critical biological processes in tumor cells in vitro was supported by increase in nuclear ΔNp63, proliferation and adhesion markers, as well as inflammatory cell infiltration in HNSCC specimens when compared to mucosa in vivo.

Figure 6. Diffuse ΔNp63, Ki67, and integrin β4 staining with inflammation in HNSCC compared to basilar staining pattern and lack of inflammation in mucosa.

A, frozen sections of tonsillar and tongue SCC with matched mucosa were stained with H&E, and ΔNp63, Ki67, Integrin β4, and pan CK antibodies by immunoperoxidase (400X, scale bar: 200μM). B, tissue array of HNSCC was immunostained and quantified using histoscore system (200X, scale bar: 200μM). Linear regression and Pearson correlation for ΔNp63 and Ki67. Coefficient of the slope and statistical significance are shown. C, ΔNp63 staining in a tongue and sinus HNSCC, with adjacent infiltrating inflammatory cells. Left panels: 400X, scale bar: 200μM. The black rectangle frames highlight the areas shown at 1000X in right panels, scale bar: 80μM.

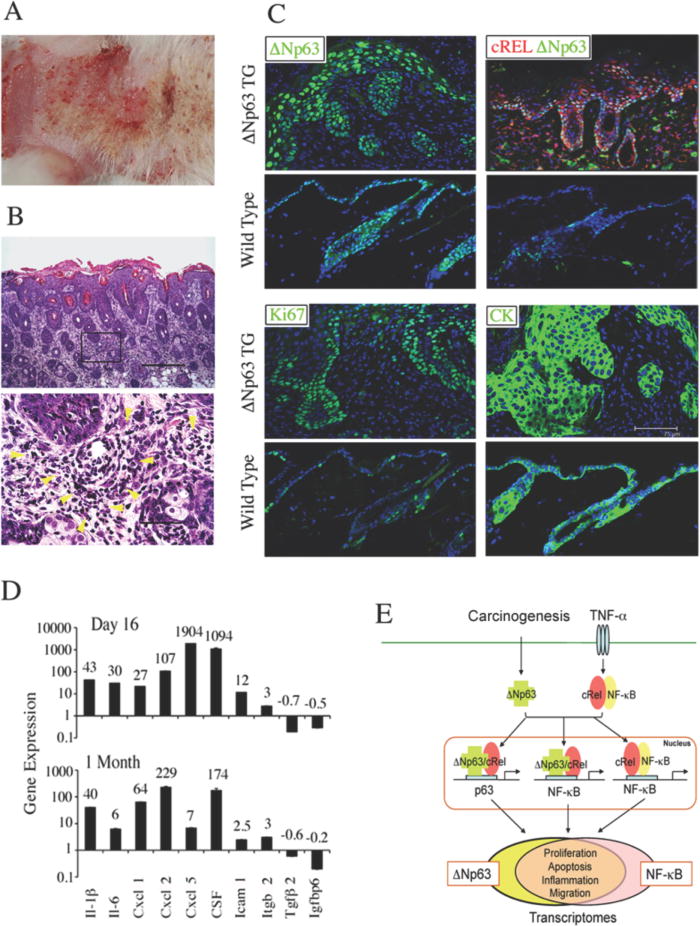

ΔNp63 transgenic (TG) mice exhibit epithelial hyperplasia and inflammation

To determine the effects of ΔNp63 overexpression in squamous epithelia in vivo, we examined a recently established transgenic (TG) mouse model in which ΔNp63α was conditionally induced in skin under the control of a keratin-5 promoter (26, 31). ΔNp63 TG mice began to develop skin lesions and erythema within one month of induction (Fig. 7A), and demonstrated hyperplastic and hyperproliferative epidermis with diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells in subadjacent stroma (Fig. 7B). In TG mice, nuclear ΔNp63 expression extended to suprabasilar layers of the hyperplastic epidermis, while the endogenous ΔNp63 expression was restricted in the innermost basal layer of the epidermis and hair follicles in wild-type mice (Fig. 7C, upper left). c-REL expression was also increased and co-localized together with ΔNp63 in epidermis, and induced in stromal infiltrating cells (Fig. 7C, upper right). As in hyperplastic human mucosa specimens (Fig. 6A, B), ΔNp63 and proliferation marker Ki67 were increased in suprabasilar layers of the thickened TG epidermis exhibiting cytokeratin-K14(CK) staining (Fig. 7C, lower panels). The altered gene expression profile expressed in skin of TG mice includes inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules and other genes expressed in UM-SCC lines (Fig. 7D). Together, these results indicate that overexpression of ΔNp63 in two independent biological systems, HNSCC and TG mice, promotes epithelial hyperproliferation, NF-κB/REL-regulated cytokine gene expression, and inflammation.

Figure 7. Skin from ΔNp63α transgenic mice demonstrates hyperplasia, cellular inflammation, and increased proinflammatory cytokine expression.

ΔNp63α was induced in skin of TG animals for two months after birth. A, gross morphology, erythematous lesions. B, Histology, H&E stain. Upper panel, epidermal hyperplasia and cellular inflammation in dorsal skin sections (100X, scale bar: 300μm); Lower panel, infiltrating inflammatory cells in the dermis highlighted by yellow arrowheads (600X, scale bar 50μm). C, dorsal skin sections from ΔNp63α TG and wild-type mice were stained with anti-ΔNp63, cRel, Ki67, and K14 (CK) antibodies and DAPI counterstain (scale bar: 75μm). D, gene expression in dorsal skin 16 days (upper), or 1 month (bottom) following ΔNp63α induction in neonatal TG mice, vs. wild-type littermates. E, Model of ΔNp63 and NF-κB/REL interactions mediating regulation of a broad gene program. Overexpressed ΔNp63 following carcinogenesis, and c-REL or RELA activated by TNF-α from inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, interact via p63 or NF-κB sequences of target gene promoters. p63/REL protein complexes regulate a broad gene program that overlaps with NF-κB transcriptome and promotes the malignant phenotype.

Discussion

Here we provide evidence for a new mechanism and model of interaction between members of the TP53 and NF-κB families, in co-regulating the transcriptome and phenotype in squamous epithelia of HNSCC and ΔNp63 TG mice (Fig. 7E). ΔNp63, the predominant p63 isoform overexpressed in most HNSCC and in the basilar layers of squamous epithelia, demonstrates a versatile ability to coordinately regulate expression of a broad program of genes that overlap the NF-κB/REL and TP53/p63 transcriptomes. Furthermore, ΔNp63 displays novel interactions with NF-κB family members, c-REL and RELA, through co-binding to newly predicted and known p63 and NF-κB promoter regulatory sites of NF-κB/REL target genes. ΔNp63 promoted proliferation, cell cycle, migration, and inflammatory cytokine expression by HNSCC in vitro. These observations are consistent with studies demonstrating an increase in ΔNp63 accompanied by proliferative and integrin adhesion protein markers, as well as inflammatory cell infiltration throughout the tumor microenvironment in vivo. In addition, the overexpression of ΔNp63α in TG mice led to suprabasilar modulation of c-REL and cytokine genes, as well as the development of hyperplasia and inflammation in the epidermis. This model supports the causal function of ΔNp63 as a key transcriptional regulator of proliferation and inflammation in squamous epithelia.

Our results demonstrate a novel bifunctional role of ΔNp63 in coordinating known NF-κB or TP53 downstream genes important in proliferation and cell survival. We demonstrated that ΔNp63 siRNA inhibited gene expression of known NF-κB target genes CCND1, BCL-2, and BCL-XL which, upon individual knockdown, were previously shown to inhibit proliferation and survival of UMSCC in vitro (25, 32–35). ΔNp63 reciprocally repressed expression and transactivation activity of TP53 family members TP53, TAp63, and p73, as well as target genes, such as p21CIP1 and PUMA, which mediate growth arrest and apoptosis. ΔNp63 was previously reported as a repressor of TP53 and p73 target genes p21Cip1, NOXA and PUMA in squamous epithelial, HNSCC, and breast cancer cells (14, 17, 27, 31). Predominant nuclear expression of ΔNp63 and deficiency of TAp63 was also observed in a subset of non-SCC tumors in mice heterozygous for p63 and TP53 alleles (36), as in human HNSCC with altered p63 and TP53 (14). Variability in the effects of ΔNp63-modulated gene expression in the UM-SCC line overexpressing mtTP53 compared to UMSCC deficient for wtTP53, suggests that effects of ΔNp63 may potentially be modified by TP53 status (22, 25, 32). ΔNp63 and TP53 share high homology of the transactivation and DNA binding domains, and differentially bind to ΔNp63/TP53 sites, and may thereby competitively inhibit or alter one another’s transactivation function (8, 9). Consistent with this, we previously found that the cross-talk between TP53 and NF-κB in differentially modulating BCL-XL and BAX expression is dampened in the subset of UM-SCC cells overexpressing mtTP53 (25, 32). The relationship between ΔNp63 and Ki67 proliferation marker histoscores in HNSCC and co-staining in suprabasilar layers of few hyperplastic mucosa samples in tissue array, as well as in skin of ΔNp63 TG mice, provide additional evidence for a relationship between increased nuclear ΔNp63 and proliferation in vivo.

A novel and unexpected finding from this study is the demonstration that ΔNp63 promotes a broad NF-κB program that includes multiple inflammatory cytokine genes. The inflammatory cytokines modulated by ΔNp63 in HNSCC cells and ΔNp63 TG mice largely overlap with the NF-κB-regulated cytokine repertoire, which we previously identified in HNSCC culture supernatants, patient serum, and tumor specimens (37, 38). Further, many of these ΔNp63 and NF-κB co-regulated inflammatory factors have been individually shown to promote the aggressive malignant behavior that leads to poor prognosis of HNSCC (4, 19, 22, 25, 37–42). Proinflammatory cytokines have been shown to attract infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages that enhance angiogenesis, and greatly promote cancer cell survival and metastasis (41). Consistent with this, we observed increased nuclear ΔNp63 is linked with infiltrating inflammatory cells in HNSCC, and in the dermis of ΔNp63 TG mice (Fig. 6C and Fig. 7B) The clinical importance of our findings that ΔNp63 promotes inflammation and aggressive malignant phenotypes is further supported by a recent report demonstrating that oral leukoplakias with increased ΔNp63 expression and inflammatory cell infiltration, exhibit a higher rate of cancer development and worse prognosis (42).

The role of ΔNp63 in modulation of multiple cell adhesion genes such as integrin α6β4 and laminins, migration by wound healing and Matrigel assays in vitro, and an association with suprabasilar integrin β4 expression in HNSCC tumors in situ, suggest it may also function in promoting cell migration during invasion/metastasis in tumor progression. Consistent with this, we previously demonstrated that increased suprabasilar α6β4 expression occurs in more than 70% of HNSCC with higher invasive/metastatic potential in a prospective clinical study, and promotes laminin mediated adhesion and migration (43, 44). In addition, a causal role for ΔNp63 in modulating a broad adhesion gene program, including β4 integrin, was independently demonstrated in breast epithelial cells (39). Knockdown of ΔNp63 by shRNA down-modulated adhesion by 24 and 48 hours, and this could be partially restored by expression of α6β4. The finding that ΔNp63 promotes a similar broad adhesion and survival gene program in HNSCC and breast cancer cell lines suggests that such dysregulation may be of broader importance in epithelial cancers.

Remarkably, we found that the promoters of multiple ΔNp63 and NF-κB modulated genes contain nearby or overlapping p63 and NF-κB binding sites (Fig. 2A), providing the potential for members of the two families to coordinately or physically interact on nearby or same site. Indeed, ΔNp63, c-REL and RELA family members demonstrated co-binding to the same or nearby promoter sites of several of these genes by ChIP and EMSA supershift analyses (Fig. 2, 3). Interestingly, while ΔNp63 co-binding with c-REL was detected on both p63 and REL regulatory sites, RELA binding was not detected on the p63 sites of IL-8, CSF2 and YAP promoters. We have also obtained evidence for binding of ΔNp63 and c-REL, but not RELA, to the p63 site of p21Cip1 promoter in primary murine keratinocytes and HNSCC by ChIP and EMSA (17, 45). In contrast, ΔNp63 co-binding with RELA was principally detected on REL sites by supershift analysis. Thus far, it appears, ΔNp63 regulates NF-κB target genes through interaction with c-REL on p63 binding sites, and with c-REL and RELA via REL sites.

Supporting a novel functional role of ΔNp63 in co-regulating NF-κB gene activation, knockdown or overexpression of ΔNp63 modulated activation of NF-κB-specific reporter and IL-8 promoter was dependent on NF-κB regulatory sites. ΔNp63α bound the NF-κB/REL site on the proximal promoter was required for ΔNp63α as well as TNF-α induced IL-8 promoter transactivation (Fig. 3, 4). Knockdown of RELA exhibited a more potent inhibitory effect than knockdown of c-REL on transactivation of the basal IL-8 reporter activity, while the relative contribution of c-REL increased when ΔNp63 was overexpressed (Fig. 4C). These data are consistent with the differential contribution of the three transcription factors to gene regulation under different conditions of activation and binding specificity. As with ΔNp63 in promoting IL-8 transcription, a recent report implicates p63 in IL-6 expression via a NF-κB promoter binding site in tonsillar crypt epithelium in palmoplantar pustulosis (46).

The broad role of ΔNp63 in both promoting NF-κB and antagonizing TP53, is consistent with its ancestral co-evolution with NF-κB as a multi-functional transcriptional coordinator (47–49). With the mutation or inactivation of TP53, aberrant activation of ΔNp63 together with NF-κB/RELs, appears to mediate a broad primordial gene program and pro-survival response. In that context, it may not be surprising that ΔNp63 serves as a master control to versatilely co-regulate NF-κB, TP53 and other gene programs to promote proliferation, survival, migration, and inflammation in cancer. Based on evidence that ΔNp63-overexpressing HNSCC and other cancers are more sensitive to cisplatin chemotherapy-induced ΔNp63 degradation (29, 50), ΔNp63 and target gene signatures may warrant further investigation as potential biomarkers for selection of cisplatin and other therapies that target ΔNp63, c-REL and REL activation in cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by NIDCD Intramural projects ZIA-DC-00016, ZIA-DC-00073 and ZIA-DC-00074 and a grant from NIH R01AR049238 (S.S.). The authors wish to thank Drs. Liesl Nottingham, Mathew Brown, Ning T Yeh (NIDCD/NIH), Chris Silvin (NHGRI/NIH) for their technical assistance; Drs. Paul Meltzer (NCI/NIH), Maranke Koster (University of Colorado, Denver), and Yong-Jun Liu (The University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) for critique of the manuscript; Drs. Kathryn E. King and Wendy C. Weinberg (FDA) for providing lysates of cells over-expressing ΔNp63 and their scientific recommendations for the project; and Drs. James W. Rocco and Leif W. Ellisen for providing ΔNp63 and TAp63 expression vectors. We also express appreciation to Ms. Cindy Clark (NIH library) for editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest were identified.

Supplemental Information includes detailed materials and methods, four figures, four tables and references.

References

- 1.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiewe T. The p53 family in differentiation and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:165–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey A, Tergaonkar V, Lane DP. Double-edged swords as cancer therapeutics: simultaneously targeting p53 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1031–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Waes C. Nuclear factor-kappaB in development, prevention, and therapy of cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1076–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tergaonkar V, Pando M, Vafa O, Wahl G, Verma I. p53 stabilization is decreased upon NFkappaB activation: a role for NFkappaB in acquisition of resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:493–503. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyi VA, Levine AJ. One billion years of p53/p63/p73 evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17609–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910634106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strano S, Dell’Orso S, Di Agostino S, Fontemaggi G, Sacchi A, Blandino G. Mutant p53: an oncogenic transcription factor. Oncogene. 2007;26:2212–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deyoung MP, Ellisen LW. p63 and p73 in human cancer: defining the network. Oncogene. 2007;26:5169–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmes DC, Bresnick E, Lubin EA, et al. Positive and negative regulation of deltaN-p63 promoter activity by p53 and deltaN-p63-alpha contributes to differential regulation of p53 target genes. Oncogene. 2003;22:7607–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanza M, Marinari B, Papoutsaki M, et al. Cross-talks in the p53 family: deltaNp63 is an anti-apoptotic target for deltaNp73alpha and p53 gain-of-function mutants. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1996–2004. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candi E, Dinsdale D, Rufini A, et al. TAp63 and DeltaNp63 in cancer and epidermal development. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:274–85. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.3.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez CA, Ott J, Mays DJ, Pietenpol JA. p63 consensus DNA-binding site: identification, analysis and application into a p63MH algorithm. Oncogene. 2007;26:7363–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koster MI, Dai D, Marinari B, et al. p63 induces key target genes required for epidermal morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3255–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocco JW, Leong CO, Kuperwasser N, DeYoung MP, Ellisen LW. p63 mediates survival in squamous cell carcinoma by suppression of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Testoni B, Borrelli S, Tenedini E, et al. Identification of new p63 targets in human keratinocytes. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2805–11. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.23.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pozzi S, Zambelli F, Merico D, et al. Transcriptional network of p63 in human keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King KE, Ponnamperuma RM, Allen C, et al. The p53 homologue DeltaNp63alpha interacts with the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway to modulate epithelial cell growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5122–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen CT, Ricker JL, Chen Z, Van Waes C. Role of activated nuclear factor-kappaB in the pathogenesis and therapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29:959–71. doi: 10.1002/hed.20615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen C, Saigal K, Nottingham L, Arun P, Chen Z, Van Waes C. Bortezomib-induced apoptosis with limited clinical response is accompanied by inhibition of canonical but not alternative nuclear factor-{kappa}B subunits in head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4175–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z, Ricker JL, Malhotra PS, et al. Differential bortezomib sensitivity in head and neck cancer lines corresponds to proteasome, nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 related mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1949–60. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan B, Yang X, Lee TL, et al. Genome-wide identification of novel expression signatures reveal distinct patterns and prevalence of binding motifs for p53, nuclear factor-kappaB and other signal transcription factors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R78. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner JC, Graham MP, Kumar B, et al. Genotyping of 73 UM-SCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Head Neck. 2010;32:417–26. doi: 10.1002/hed.21198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thurfjell N, Coates PJ, Vojtesek B, Benham-Motlagh P, Eisold M, Nylander K. Endogenous p63 acts as a survival factor for tumour cells of SCCHN origin. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:1065–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee TL, Yang XP, Yan B, et al. A Novel Nuclear Factor-{kappa}B Gene Signature Is Differentially Expressed in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Association with TP53 Status. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5680–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romano RA, Ortt K, Birkaya B, Smalley K, Sinha S. An active role of the DeltaN isoform of p63 in regulating basal keratin genes K5 and K14 and directing epidermal cell fate. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westfall MD, Mays DJ, Sniezek JC, Pietenpol JA. The Delta Np63 alpha phosphoprotein binds the p21 and 14-3-3 sigma promoters in vivo and has transcriptional repressor activity that is reduced by Hay-Wells syndrome-derived mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2264–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2264-2276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ondrey FG, Dong G, Sunwoo J, et al. Constitutive activation of transcription factors NF-(kappa)B, AP-1, and NF-IL6 in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines that express pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic cytokines. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26:119–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199910)26:2<119::aid-mc6>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatterjee A, Chang X, Sen T, Ravi R, Bedi A, Sidransky D. Regulation of p53 family member isoform DeltaNp63alpha by the nuclear factor-kappaB targeting kinase IkappaB kinase beta. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1419–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori N, Mukaida N, Ballard DW, Matsushima K, Yamamoto N. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax transactivates human interleukin 8 gene through acting concurrently on AP-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB-like sites. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3993–4000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romano RA, Smalley K, Liu S, Sinha S. Abnormal hair follicle development and altered cell fate of follicular keratinocytes in transgenic mice expressing DeltaNp63alpha. Development. 2010;137:1431–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.045427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee TL, Yeh J, Friedman J, et al. A signal network involving coactivated NF-kappaB and STAT3 and altered p53 modulates BAX/BCL-XL expression and promotes cell survival of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1987–98. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown MS, Diallo OT, Hu M, et al. CK2 modulation of NF-kappaB, TP53, and the malignant phenotype in head and neck cancer by anti-CK2 oligonucleotides in vitro or in vivo via sub-50-nm nanocapsules. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2295–307. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pernas FG, Allen CT, Winters ME, et al. Proteomic signatures of epidermal growth factor receptor and survival signal pathways correspond to gefitinib sensitivity in head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2361–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worden B, Yang XP, Lee TL, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor differentially regulates expression of proangiogenic factors through Egr-1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7071–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flores ER, Sengupta S, Miller JB, et al. Tumor predisposition in mice mutant for p63 and p73: evidence for broader tumor suppressor functions for the p53 family. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:363–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Z, Malhotra PS, Thomas GR, et al. Expression of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1369–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen C, Duffy S, Teknos T, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB-related serum factors as longitudinal biomarkers of response and survival in advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3182–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carroll DK, Carroll JS, Leong CO, et al. p63 regulates an adhesion programme and cell survival in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:551–61. doi: 10.1038/ncb1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z, Ehsanian R, Van Waes C. Nuclear Transcription Factors and Signal Pathways. In: Myers J, editor. Oral Cancer Metastasis. New York: Springer Science and Human Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richmond A. Nf-kappa B, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:664–74. doi: 10.1038/nri887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saintigny P, El-Naggar AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, et al. DeltaNp63 overexpression, alone and in combination with other biomarkers, predicts the development of oral cancer in patients with leukoplakia. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6284–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Waes C, Kozarsky KF, Warren AB, et al. The A9 antigen associated with aggressive human squamous carcinoma is structurally and functionally similar to the newly defined integrin alpha 6 beta 4. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Waes C, Surh DM, Chen Z, et al. Increase in suprabasilar integrin adhesion molecule expression in human epidermal neoplasms accompanies increased proliferation occurring with immortalization and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5434–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H, Chen Z, Yang X, et al. TNF-a induced c-REL interacts with deltaNp63, displacing TAp73 to inhibit growth arrest and apoptosis in head and neck cancers (Abstract # 3900). 101th Annunal Meeting of American Association for Cancer Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koshiba S, Ichimiya S, Nagashima T, et al. Tonsillar crypt epithelium of palmoplantar pustulosis secretes interleukin-6 to support B-cell development via p63/p73 transcription factors. J Pathol. 2008;214:75–84. doi: 10.1002/path.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang A, Zhu Z, Kapranov P, et al. Relationships between p63 binding, DNA sequence, transcription activity, and biological function in human cells. Mol Cell. 2006;24:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vigano MA, Mantovani R. Hitting the numbers: the emerging network of p63 targets. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:233–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.3.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan JC, Kalaitzidis D, Gilmore TD, Finnerty JR. Rel homology domain-containing transcription factors in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leong CO, Vidnovic N, DeYoung MP, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. The p63/p73 network mediates chemosensitivity to cisplatin in a biologically defined subset of primary breast cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1370–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.