Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to expand the research on psychiatric complications of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), as well as to examine the prevalence of a broad range of psychopathology in diabetic and non-diabetic hemodialysis (HD) patients.

Methods

One hundred nineteen HD patients were invited to enter the cross-sectional study. To assess quality of life, quality of sleep, mental status and depression and anxiety symptoms, the 36-item Short Form, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Mini-Mental State Examination and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, respectively, were used.

Results

The mean age of all patients was 56.9±16.1 years; 54 (45.4%) were female. In the diabetic patients group, 84.8% of the patients had low MCS scores, and 89.2% patients had low PCS scores; 73.9% were poor sleepers; 63.0% had cognitive decline; 62.0% patients were depressive symptoms; and 28.3%had symptoms of anxiety. When comparing the diabetic and non-diabetic patients, the diabetic patients had lower role-emotional, sleep duration, and sleep efficiency scores.

Conclusions

Incorporating a standard assessment and, eventually, treatment of psychopathologic symptoms into the care provided to diabetic and hemodialysis patients might improve quality of life and sleep, depressive symptoms and, reduce mortality risk.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, hemodialysis patients, diabetes mellitus, quality of sleep, quality of life

Introduction

Hemodialysis (HD) patients may face serious stressors related to the illness and its treatment, arising from the chronic nature of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1,2]. They are often confronted with limitations in food and fluid intake, physical symptoms such as itching and lack of energy, and psychological stressors such as loss of self-concept and self-esteem, feelings of uncertainty about the future, feelings of guilt toward family members, and problems in the social domain [3,4]. It is worth noting that ESRD is a disease with serious effects on patients' quality of life (QOL), negatively affecting their social, financial, and psychological wellbeing. The physical component score derived from the SF-36 is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with diabetes on hemodialysis who generally have very low QOL scores [5].

Sleep complaints are common in hemodialysis patients and are associated with lower QOL [6]. It has been reported that 80% of hemodialysis patients suffer from sleep abnormalities, and the prevalence is higher than that in the general population. Both poor sleep and depression in HD patients have been associated with reduced QOL and increased mortality risk [6-9].In diabetic patients, incidence of sleep disturbances, as well as morbidity and mortality, are substantially higher than in their non-diabetic counterparts [10].

Research suggests that chronic kidney disease (CKD) results in substantial impairment in many neurocognitive domains, including attention and processing speed [11-13]. Patients with CKD constitute a high-risk population for cognitive decline, as CKD is frequently caused by diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension. Hypertensive and diabetic patients present a higher tendency toward loss of mental agility than healthy individuals [14,15].

Patients with ESRD undergoing hemodialysis show important psychiatric morbidity, particularly increased depression and anxiety [16,17]. Depression is associated with diminished perception of quality of life. This high rate of depression impacts QOL and has been shown to be related to functional impairment and life satisfaction [18-20].

The objective of this study was to evaluate quality of sleep and quality of life by diabetic and non-diabetic patients undergoing regular hemodialysis. This objective includes correlating quality of sleep with the physical, mental, emotional and social domains of a multidimensional instrument; the effects of renal disease on daily life; whether the disease has prevented the patient from undertaking paid employment; quality of social interaction; and sleep. The impact of ESRD on quality of life, sleep quality and the clinical, and laboratory variables that may be correlated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and gross measure of mental status were examined in diabetic and non-diabetic HD patients.

Methods

Herein we present a cross-sectional multicentric study of HD patients undergoing hemodialysis in Kütahya State Hospital and private dialysis center. The criteria for inclusion in the study were: individual patients older than18 years of age; ESRD patients undergoing hemodialysis for at least six months in the absence of other diseases, such as cancer, cardiac or pulmonary failure, or neurological problems due to associated brain disease; and the ability to understand the purpose of the research and answer the questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included inability to answer to the questionnaires (deafness, reading problems); previous diagnosis of psychotic or neurological disorders or dementia; decompensation of physical conditions, requiring hospital admission; stressful life events in the 30 days prior to the study (e.g., death of a relative/friend, personal illness, personal accident, or accident affecting someone close, change in economic situation, change of work or home and divorce/separation). Diabetes (n=46) was considered present if a patient was treated with insulin or oral agents or had a fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. All of the variables were measured concurrently. The study protocol was approved by Local Ethics Committee of Selçuk University.

Dialysis strategies

The hemodialysis patients included in this study were undergoing three weekly sessions of hemodialysis that lasted 3-4 hours, using standard bicarbonate low-flux dialysis on polysulfone filters. Vascular access was via arteriovenous fistula in the upper limbs and permanent catheter. Adequacy of dialysis (Kt/V) for urea was calculated using the single-compartment model of Daugirdas and standard urea removal ratio using [URR = 100 (1 - R), where R = post-dialysis urea/pre-dialysis urea].

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured with the 36-item Short Form (SF-36) [21]. This instrument has been used extensively in populations of patients with renal disease. The SF-36 is a 36-item self-administered questionnaire that yields scores for eight domains of life (physical functioning, role limitations-physical, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations-emotional, and mental health), as well as two summary scores, a mental component summary score (MCS), and a physical component summary score (PCS). Each of the eight domains is scored on a scale of 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. The MCS and PCS scores are standardized to a mean (SD) of 50 [22], with scores below 50 indicating low average functioning.

Quality of sleep

Quality of sleep was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [23]. This self-administered questionnaire assesses quality of sleep during the previous month and contains 19 self-rated questions yielding seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored from 0 to 3, yielding a global PSQI score between 0 and 21, with higher scores indicating lower quality of sleep. The PSQI is useful in identifying good and poor sleepers. A global PSQI score >5 indicates that a person is a “poor sleeper,” having severe difficulties in at least two areas or moderate difficulties in more than three areas [23].

Mental status

Mental status was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which was developed by Folstein at al [24]. The MMSE is a brief 30-point questionnaire that is used to screen for cognitive impairment. MMSE is an 11-question measure that tests five areas of cognitive function: orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and language; the maximum score is 30. This test has been extensively used in HD patients. MMSE scores <24 indicated that a person has presence of mental decline [24]. However, the MMSE is not measure of neurocognitive functioning; it is a gross measure of mental status.

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Depressive disorder and ESRD can have similar physical symptoms, so there is a need for a practical, clinical, applicable screening tool that does not focus on the shared symptomatology [25].

HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith [26] in 1983 to identify caseness of anxiety disorders and depression among patients in non-psychiatric hospital clinics. It was divided into an anxiety subscale (HAD-A) and a depression subscale (HAD-D). The Turkish version of the HADS used in this study has been validated by Aydemir et al. [27]. Aydemir suggested a cutoff value of the anxiety subscale as 10/11 and the depression subscale as 7/8. Accordingly, participants with those or higher scores are considered to be at risk.

Other variables

We collected comprehensive socio-demographic information, cause of renal disease, time on dialysis and comorbid conditions, by interview and chart review. A monthly income of 500 USD ($) was designated as low economic status; 500-1500 $ was designated as medium financial status, and above 1500 $ was designated as good economic status. Peripheral venous blood samples were drawn from the HD patients just before the start of dialysis during a midweek session. Serum glucose, albumin, calcium, phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), and complete blood count were measured.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 15 statistical software. Variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or frequency. The data had previously been submitted to anormality test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov). The correlation between data was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation test and linear regression analysis. The differences between the two groups were compared with the independent samples t-tests. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was p <0.05.

Results

One hundred nineteen patients were invited to enter the cross-sectional study. The mean age was 56.9±16.1 years; 54 (45.4%) were female. The characteristics of the diabetic (n=46) and non-diabetic 119 patients are shown in Table 1. The causes of renal disease were: diabetic nephropathy, 28; unknown, 46; hypertension, 22; chronic pyelonephritis, 2; nephrolithiasis, 4; amyloidosis, 5; glomerulonephritis, 10; polycystic kidney disease,1;and systemic lupus erythematosus, 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the diabetic and non- diabetic 119 patients included in the study

| Variable | Diabetic | Non diabetic |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean ± SD (range) | 58.7±12.1(22-79) | 55.8±18.1 (22-90) |

| Female/male n (%) | 22 /24 (47.8/ 52.2 ) | 32/41 (43.8/56.2) |

| Dialysis duration (month) | 40.7±30.9 (6-119) | 59.3±51.0 (6-216) |

| Residual urine mL/24 h | 121.7± 252.9(0-1000) | 61.4±179.6 (0-1000) |

| Coronary artery disease n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 10 (13.7) |

| Congestive heart failure n (%) | 13 (28.3) | 14 (19.1) |

| Smoking n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 12 (16.4) |

| Arteriovenous fistula/catheter n (%) | 42/4 (91.3/8.7) | 61/12 (83.6/16.4) |

| Living alone (single or widow) n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 27 (37.0) |

| Living with someone n (%) | 37 (80.4) | 46 (63.0) |

| Illiterate n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 10 (13.7) |

| Literate n (%) | 8 (17.4) | 18 (24.7) |

| Primary school education n (%) | 35 (76.1) | 29 (39.7) |

| Middle school graduate n (%) | 3 (4.3) | 7 (9.6) |

| High school graduate n(%) | - | 9 (12.3) |

| University n (%) | - | - |

| Low economic status n (%) | 24 (52.2) | 37 (50.7) |

| Medium financial situation n (%) | 20 (43.5) | 32 (43.8) |

| Good economic situation n(%) | 2 (4.3) | 4 (5.5) |

In the total group of 119 patients, the mean MCS and PCS were lower than the standardized average of 50. Eighty-nine (74.8%) patients had low MCS scores (MCS scores<50), and 103 (86.6%) had low PCS scores (PCS<50). Ninety-two (77.3%) patients were poor sleepers (global PSQI >5). Sixty-seven (56.3%) patients had cognitive decline (MMSE scores<24). Seventy-one (59.7%) patients had depressive symptoms (depression scores>7), and 27 (22.7%) patients were anxious (anxiety scores>10). In the diabetic patients group, 84.8% had low MCS scores, and 89.2% had low PCS scores; 73.9% were poor sleepers; 63.0% had cognitive decline; 62.0% patients had depressive symptoms; and 28.3% patients had anxiety symptoms. In the non- diabetic patients group, 68.5% had low MCS scores, and 84.9% had low PCS scores; 79.50% were poor sleepers; 52.1% had cognitive decline; 56.2% patients had depressive symptoms; and 19.2% patients had anxiety symptoms. The mean ± SD scores for SF-36 MCS and PCS, quality of sleep, MMSE, and HADS depression and anxiety domains of diabetic and non- diabetic all patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The mean ± SD (range) scores for global and component PSQI, SF-36 MCS and PCS, MMSE, and HAD depression and anxiety domains for all patients

| Variable | All patients | Diabetic | Non-diabetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | |||

| MCS | 40.8± 10.4 | 37.7±9.6 | 41.8±10.5 |

| PCS | 39.0±8.2 | 38.5±6.3 | 39.2±8.8 |

| Physical functioning | 50.8± 28.2 | 47.2±26.7 | 52.0±28.7 |

| Role-physical | 42.0± 36.8 | 35.6±37.5 | 44.0±36.6 |

| Bodily pain | 58.3± 23.0 | 58.2±21.2 | 58.3±23.7 |

| General health | 45.0± 12.9 | 41.0±11.6 | 46.4±13.1 |

| Vitality | 52.2± 22.5 | 47.6±21.0 | 53.7±22.9 |

| Social functioning | 58.3± 25.4 | 55.6±24.7 | 59.2±25.7 |

| Role-emotional | 37.3± 36.4 | 25.3±31.7 | 41.3±37.1 |

| Mental health | 54.9± 21.3 | 51.2±21.5 | 56.2±21.2 |

| Quality of sleep | |||

| Global PSQI | 7.8± 2.8 | 7.4±2.8 | 7.9±2.8 |

| Sleep quality | 1.1± 0.7 | 1.1±0.6 | 1.2±0.8 |

| Sleep latency | 1.4± 0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | 1.3±0.8 |

| Sleep duration | 0.8± 0.7 | 0.5±0.6 | 0.9±0.7 |

| Sleep efficiency | 1.4± 1.4 | 0.8±1.2 | 1.5±1.4 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1.7± 0.6 | 1.7±0.5 | 1.7±0.6 |

| Use of sleep medications | 0.7± 0.8 | 0.7±0.9 | 0.7±0.8 |

| Day time dysfunction | 1.1± 0.7 | 7.4±2.8 | 7.9±2.8 |

| MMSE | 22.0± 4.5 | 21.9±3.5 | 22.0±4.8 |

| HAD | |||

| Depression | 8.1± 4.3 | 8.2±3.8 | 8.1±4.5 |

| Anxiety | 7.3± 3.8 | 7.0±3.8 | 7.5±3.8 |

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; MCS: SF-36 Mental Component Summary; PCS: SF- 36 Physical Component Summary; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; HSD: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

In the total 119 patients, the correlations between MCS and PCS and the other continuous variables are shown in Table 3. We found an inverse correlation between MCS and PTH. In addition, there was a significant inverse correlation between PCS and global PSQI scores. Global PSQI was correlated with dialysis duration (r=0.250, p=0.007), PTH (r=0.217, p=0.019), anxiety (r=0.246, p=0.008), depressive symptoms (r=0.210, p=0.024). There were significant inverse correlations of global PSQI score with PCS (r=-0.228, p=0.014), physical functioning (r=-0.237, p=0.010), bodily pain (r=-0.233, p=0.011), and MH (r=-0.306, p=0.001), MMSE scores (r=-0.199, p=0.031). MMSE scores were correlated with age (r=-0.697, p< 0.001), sleep quality (r=-0.283, p=0.017), sleep disturbance (r=-0.349, p=0.003), creatinine levels (r=0.463, p<0.001), urea levels (r=0.252, p=0.035), Kt/V (r=-0.241, p=0.046), phosphor (r=0.345, p=0.004), anxiety (r=-0.272, p=0.023), depression (r=-0.364, p=0.002).

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients for the SF-36 MCS and PCS and other continuous variables among the 119 study patients

| Variable | MCS | PCS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| r | p | r | p | |

| Age | -0.017 | NS | -0.442 | <0.001 |

| Albumin | -0.055 | NS | 0.264 | 0.005 |

| PTH | -0.224 | 0.016 | -0.002 | NS |

| Mini-Mental Status Examination | 0.411 | <0.001 | -0.289 | 0.002 |

| Depression | -0.547 | <0.001 | -0.463 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | -0.486 | <0.001 | -0.359 | <0.001 |

| Global PSQI | -0.086 | NS | -0.228 | 0.014 |

| Subjectivesleepquality | -0.271 | 0.003 | -0.208 | 0.025 |

| Sleeplatency | 0.062 | NS | 0.010 | NS |

| Sleepduration | 0.021 | NS | -0.016 | NS |

| Sleepefficiency | 0.073 | NS | 0.105 | NS |

| Sleepdisturbance | -0.200 | 0.032 | -0.373 | <0.001 |

| Use of sleepmedications | 0.006 | NS | -0.189 | 0.043 |

| Daytimedysfunction | -0.224 | 0.016 | -0.274 | 0.003 |

r, correlationcoefficient; p, p-valueforthe correlation; MCS, SF-36 Mental Component Summary; PCS, SF-36 Physical Component Summary; PTH, Parathyroidhormone; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

When we performed linear regression analysis, independent predictor of MCS was depression scores (β=-0.404, p=0.001). Independent predictors of PCS were albumin (β=0.241, p=0.002), sleep disturbances (β=-0.280, p=0.015), and depression scores (β=-0.260, p=0.014). Independent predictors of global PSQI scores was dialysis duration (β=0.249, p=0.009). Independent predictor of global PSQI scores were age (β=-0.614, p<0.001), sleep quality (β=-0.190, p=0.020), Kt/V (β=-0.242, p=0.004), phosphor (β=-0.196, p=0.049). Independent predictor of MMSE scores were age (β=-0.614, p<0.001), sleep quality (β=-0.190, p=0.020), Kt/V (β=-0.242, p=0.004), phosphor (β=-0.196, p=0.040). Independent predictor of depressive symptom scores were residual urine (β=-0.204, p=0.006), creatinine (β=-0.248, p=0.019), Kt/V (β=-0.242, p=0.004), vitality (β=-0.291, p=0.012).

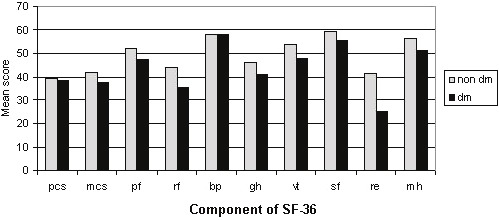

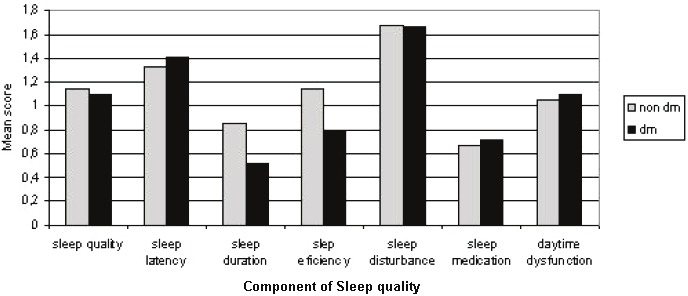

When comparing diabetic patient with non-diabetic patients, glucose levels, PTH, role-emotional (Figure 1), sleep duration, and sleep efficiency (Figure 2) scores were different in the two groups. The characteristics of the diabetic patients compared with the non-diabetic patients are shown in Table 4. The mean PCS, MCS, and global PSQI scores were not statistically different between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Mean scores for components of the SF- 36 for the 119 diabetic and non-diabetic hemodialysis patients. Pcs, SF- 36 Physical Component Summary; mcs, SF- 36 Mental Component Summary; pf, Physical functioning; rf, Role physical; bp, Bodily pain; gh, General health; vt, Vitality; sf, Social functioning; re, Role emotional; mh, Mental health.

Figure 2.

Mean scores for components of the PSQI for the 119 diabetic and non-diabetic hemodialysis patients.

Table 4.

Characteristics of diabetics compared to non-diabetics among the 119 patients in the study

| Variable | Diabetic | Non-Diabetic | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 145.0±71.6 | 99.7±20.1 | 0.002 |

| Parathyroid hormone | 350.6±254.6 | 585.9±471.5 | 0.004 |

| MCS | 37.7±9.6 | 41.8±10.5 | NS |

| PCS | 38.5±6.3 | 39.2±8.8 | NS |

| Role-emotional | 25.3±31.7 | 41.3±37.1 | 0.040 |

| Global PSQI | 7.4±2.8 | 7.9±2.8 | NS |

| Sleep duration | 0.5±0.6 | 0.9±0.7 | 0.019 |

| Sleep efficiency | 0.8±1.2 | 1.5±1.4 | 0.008 |

Mann-Whitney test was used. The level of significance was p <0.05. MCS: SF-36 Mental Component Summary; PCS: SF-36 Physical Component Summary; MMSE: Mini-Mental Status Examination; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Discussion

This study sought to explore the range and extent of psychopathology in diabetic HD patients. Information on 119 diabetic and non-diabetic patients from the HD center was gathered. This is the first known report on the full spectrum of psychiatric symptomatology determined systematically in a diabetic hemodialysis population. The present study, showed that compared to non-diabetic HD patients, diabetic HD patients had worse role-emotional, sleep duration, and sleep efficiency scores.

Hemodialysis significantly and adversely affects the lives of patients, both physically and psychologically. The global influence on family roles, work competence, fear of death, and dependency on treatment may negatively affect quality of life and exacerbate feelings associated with a loss of control. Deficits of QOL may be associated with treatment, as hemodialysis imposes serious restrictions on the patient's life due to dependence on the dialysis machine [1]. Cukor et al. [28] reported that the mean score for all patients on the SF-36 was 50.1±70.3. In the present study, MCS and PCS were 40.8±10.4 and 39.0±8.2, respectively. Our mean scores for all patients and diabetic patients on the SF-36 were lower than the results of Cukor et al. In our study, MCS correlated with PTH, depression, and anxiety; PCS correlated with age, albumin, depression, and anxiety. However, independent predictor of MCS was depression scores; independent predictors of PCS were albumin, sleep disturbances, and depression scores.

In the study by Apostolouet al, as a whole, dialysis patients scored poorly as far as the physical domain was concerned, but they had good mental adaptation. In their study, diabetic dialysis patients also exhibited worse QOL for physical functioning, energy, vitality, and eating/drinking limitations [29]. When compared to a control non-diabetic group, Gumprecht et al. found that physical health was significantly impaired in diabetic dialysis patients [30]. In the present study, MCS, PCS, and almost all domains of SF-36 for diabetic patients were lower than in the non-diabetic patients. Our diabetic dialysis patients scored poorly mental component domain than non diabetic group’s mental component.

Many studies have found a correlation between psychological factors, such as depression, anxiety, and social worry, and sleep quality impairment in chronic HD patients. In the present study, global PSQI ranged from 2 to 15, and the prevalence of poor sleep was 77.3%, which is comparable with the 70-80% prevalence of sleep-wake complaints in dialysis patients reported in previous studies [6,9]. In the present study, 73.9% of diabetic patients were poor sleepers, and their sleep duration and efficiency scores were lower than those of the non-diabetic patients. However percentage of high global PSQI scores for non-diabetic patients than diabetics. Han et al. [10] found that age, nutritional status, and depression were the major risks for sleep disturbance in diabetic patients. In our study, sleep disorders correlated with dialysis duration and PTH. In our study, consistent with the findings of Iliescu [6] and Holley [31], mental QOL was associated with subjective sleep quality, sleep disturbance, and daytime dysfunction, while physical QOL was associated with subjective sleep quality; sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The association between sleep quality and QOL may be explained by a direct influence of sleep quality on QOL.

Prior research has indicated that there may be a direct relationship between ESRD severity and neuro-cognitive impairment [32-34]. Murray et al. [13] found, in a large sample of HD patients, that 90% of the cohort had impairments in select neuropsychological measures of global cognitive function, verbal and visual learning and memory, and inhibition. Sánchez-Román et al. [11] found that 23% of patients with ESRD showed impairment in global cognitive function, while we found that 56.3% of patients with ESRD showed impairment in global cognitive function. There are multiple other factors that are relevant when evaluating the impact of CKD on cognitive function, including the presence of anemia, hypertension, diabetes [11,32], depression, somnolence, 24-hr urine volume, creatinine levels, urea levels, albumin levels, lower levels of Kt/V, hemoglobin, parathyroid hormone levels, and high cholesterol levels. In the present study, 63.0% of our diabetic HD patients had global cognitive function impairment. The percentage of cognitive declines our diabetic patient than non- diabetic patients. In our study, impairment in global cognitive function was related to age, Kt/V, URR, and phosphorus levels.

In their study, Garcia et al. [4] found that the incidence of depression was frequent in 68.1% of ESRD patients. Other authors reported a lower frequency of depression, with rates of 25.3% [28], 20% [35], and 8.1% [36], while our incidence of depression was 59.7%. This difference may be due to the fact that we considered mild depression, whereas the other authors assessed only severe depression. Those with a persistent course of depression had marked decreases in quality of life and self-reported health status [37]. In the non- diabetic patients group, 62.0% patients had depressive symptoms. This percentage was higher than non- diabetic patients. Bossola et al. found that depression scores correlated significantly with age, SF-36 scores, MMSE, creatinine, and albumin levels [38]. In the present study, depression scores correlated significantly with residual urine, creatinine, Kt/V, vitality. We can hypothesize that such correlations are an expression of a relationship between depressive symptoms and dialysis adequacy and nutritional status. Uncertainty regarding the future and fear of losing control in life are important factors associated with anxiety that adversely affect emotional stability. In this study, our anxiety percentage of HD patients was 22.7%. Diabetic HD patients had higher anxiety scores than non-diabetic patients. In the diabetic patients, higher percentage anxiety and depressive symptoms may be due to additional problems caused by diabetes such as application of insulin, diabetic retinopathy.

The present study has some limitations. First, methodological limitations of this study include the lack of an age- and sex-matched community comparison group. Secondly, this is a cross-sectional study, and the causal inferences of anxiety, depression, and reduced quality of life and sleep remain unclear. Although this cross-sectional design could not determine causal relationships, this study provides a path-analysis for the complex relationships among depression, anxiety, quality of life, and sleep in hemodialysis patients. Despite these limitations, there were also methodological strengths, in that we used random selection within each dialysis shift and both self-reported and clinician reported measures of psychopathology.

In conclusion, diabetic patients had lower role-emotional, sleep duration, and sleep efficiency scores than non-diabetic patients. Incorporating a standard assessment and, eventually, treatment of psychopathologic symptoms into the care provided both diabetic and non-diabetic hemodialysis patients might improve psychological well-being, quality of life and sleep, and, consequently, reduce mortality risk in this population.

References

- 1.Ginieri-Coccossis M, Theofilou P, Synodinou C, Tomaras V, Soldatos C. Quality of life, mental health and health beliefs in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: investigating differences in early and later years of current treatment. BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alavi NM, Aliakbarzadeh Z, Sharifi K. Depression, anxiety, activities of daily living, and quality of life scores in patients undergoing renal replacement therapies. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3693–3696. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covic A, Seica A, Gusbeth-Tatomir P, Gavrilovici O, Goldsmith DJ. Illness representations and quality of life scores in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2078–2083. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia TW, Veiga JP, da Motta LD, de Moura FJ, Casulari LA. Depressed mood and poorquality of life in male patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32:369–374. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010005000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashino Y, Fukuhara S, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Saito S, Kurokawa K. Low health-related quality of life is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes on haemodialysis: the Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Pattern Study. Diabet Med. 2009;26:921–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliescu EA, Coo H, McMurray MH, Meers CL, Quinn MM, Singer MA, Hopman WM. Quality of sleep and health-related quality of life in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:126–132. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paparrigopoulos T, Theleritis C, Tzavara C, Papadaki A. Sleep disturbance in haemodialysis patients is closely related to depression. GenHosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:175–177. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, Fissell R, Andreucci VE, Fukuhara S, Rayner HC, Furniss AL, Port FK, Saran R. Sleep quality predicts quality of life and mortality risk in haemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:998–1004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabry AA, Abo-Zenah H, Wafa E, Mahmoud K, El-Dahshan K, Hassan A, Abbas TM, Saleh Ael-B, Okasha K. Sleep disorders in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han SY, Yoon JW, Jo SK, Shin JH, Shin C, Lee JB, Cha DR, Cho WY, Pyo HJ, Kim HK, Lee KB, Kim H, Kim KW, Kim YS, Lee JH, Park SE, Kim CS, Wea KS, Oh KS, Chung TS, Suh SY. Insomnia in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Prevalence and risk factors by a multicenter study. Nephron. 2002;92:127–132. doi: 10.1159/000064460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sánchez-Román S, Ostrosky-Solís F, Morales-Buenrostro LE, Nogués-Vizcaíno MG, Alberú J, McClintock SM. Neurocognitive profile of an adult sample with chronic kidney disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:80–90. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Luan J, Yaffe K. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1863–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, Gilbertson DT, Pederson SL, Li S, Smith GE, Hochhalter AK, Collins AJ, Kane RL. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67:216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Condé SA, Fernandes N, Santos FR, Chouab A, Mota MM, Bastos MG. Cognitive decline, depression and quality of life in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, Cummings SR, Harris T, Simonsick E, Satterfield S, Ayonayon H, Yaffe K. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gençöz F, Gençöz T, Soykan A. Psychometric properties of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and other physician-rated psychiatric scales for the assessment of depression in ESRD patients undergoing hemodialysis in Turkey. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:450–459. doi: 10.1080/13548500600892054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmel PL, Thamer M, Richard CM, Ray NF. Psychiatric illness in patients with end-stage renal disease: A critical comparison of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. Am J Med. 1998;105:214–221. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimmel PL, Cukor D, Cohen SD, Peterson RA. Depression in end-stage renal disease patients: a critical review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:328–334. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, Friedman S, Newville H, Safier M, Spielman LA, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Anxiety disorders in adults treated by hemodialysis: a single-center study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:128–136. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, Alleyne S, Cruz I, Veis JH. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, Seddon P, Zeidel ML. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:609–613. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valderrabano F, Jofre R, Lopez-Gomez JM. Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:443–464. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.26824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein S, Mc Hugh PR. Mini Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riezebos RK, Nauta KJ, Honig A, Dekker FW, Siegert CE. The association of depressive symptoms with survival in a Dutch cohort of patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:231–236. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydemir Ö, Güvenir T, Küey L. Hastane Anksiyete ve Depresyon Ölçeği Türkçe formunun geçerlilik ve Güvenilirliği. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 1997;8:280–287. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, Friedman S, Cromwell-Smith A, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Depression and anxiety in urban hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am SocNephrol. 2007;2:484–490. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apostolou T, Hutchison AJ, Boulton AJ, Chak W, Vileikyte L, Uttley L, Gokal R. Quality of life in CAPD, transplant, and chronic renal failure patients with diabetes. Ren Fail. 2007;29:189–197. doi: 10.1080/08860220601098862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gumprecht J, Zelobowska K, Gosek K, Zywiec J, Adamski M, Grzeszczak W. Quality of life among diabetic and non-diabetic patients on maintenance haemodialysis. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:205–208. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1192023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holley JL, Nespor S, Rault R. A comparison of reported sleep disorders in patients on chronic hemodialysis and continuous peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;19:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes--systematic overview of prospective observational studies. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2460–2469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elias MF, Elias PK, Seliger SL, Narsipur SS, Dore GA, Robbins MA. Chronic kidney disease, creatinine and cognitive functioning. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2446–2452. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kutlay S, Nergizoglu G, Duman N, Atli T, Keven K, Ertürk S, Ates K, Karatan O. Recognition of neurocognitive dysfunction in chronic hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2001;23:781–787. doi: 10.1081/jdi-100108189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson S, Dwyer A. Patient perceived barriers to treatment of depression and anxiety in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2008;69:201–206. doi: 10.5414/cnp69201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craven JL, Rodin GM, Johnson L, Kennedy SH. The diagnosis of major depression in renal dialysis patients. Psychosomat Med. 1987;49:482–492. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1599–1613. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bossola M, Ciciarelli C, Di Stasio E, Conte GL, Vulpio C, Luciani G, Tazza L. Correlates of symptoms of depression and anxiety in chronic hemodialysis patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]