Abstract

Chiral 1,2-diols are prepared from chiral α-aminoxylated aldehydes or cyclohexanone and Grignard reagents in high diastereoselectivities (>87:13 dr) and high enantioselectivities (>93% ee). The presence of the ate complex of CeCl3·2LiCl is essential for the high overall yields and high stereoselectivities. The N-O bond of α-aminoxylated carbonyl compound is cleaved by organometallic reagent.

Keywords: diastereoselective synthesis; chiral 1,2-diol synthesis; asymmetric O-nitrosoaldol reaction; CeCl3·2LiCl ate complex

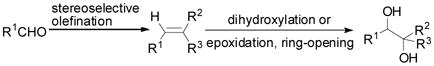

1,2-Diol units are frequently found in natural products, such as carbohydrates, polyketides and alkaloids,[1] and chiral 1,2-diols are used as chiral ligands and auxiliaries in stereoselective syntheses.[2, 3] Generally, chiral 1,2-diols are obtained either by oxidation of an olefin[4] or ring opening of an epoxide [Eq. (1)].[5] Although such a process can be rendered asymmetric through the use of chiral catalyst, it either requires toxic transition metal catalysts or suffers from lower regioselectivity. Furthermore, for high selectivity stereochemically pure olefins are required for both methods. We considered a very different strategy to prepare these 1,2-diols that makes use of organocatalytic oxidation of carbonyl compounds followed by Grignard additions [Eq. (2)].

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Our previous results indicated that nitrosoaldol reaction gives α-oxo or α-aza carbonyl derivatives with virtually complete stereoselectivities.[6, 7] This species should subsequently undergo simple addition reaction of Grignard reagents. However, the actual execution of this strategy has some problems. First, the intermediary aminoxycarbonyl compounds are usually rather unstable. Particularly, aminoxy aldehydes are exceedingly unstable and difficult to handle. Thus, a one-pot procedure or sequential process is required. Second, the subsequent Grignard addition reaction should be highly diastereoselective. Otherwise, the produced diol has to be purified, which is frequently rather difficult. Third, the resulting product should be transformed to 1,2-diol by cleaving N-O bond. Reported herein is our successful procedure, which satisfies all these requirements.

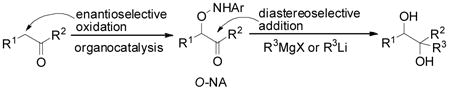

Using L-proline based tetrazole 1 as the catalyst,[7h] reaction of 2-nitrosotoluene with isovaleraldehyde in DMSO gave the O-selective nitrosoaldol (O-NA) product in high yield within 15 minutes (Table 1). We have discovered that the O-NA reaction proceeds much more cleanly with 2-nitrosotoluene than with nitrosobenzene, probably due to suppression of the N-O bond cleavage of the O-NA product caused by nitroso compounds.[8] Since DMSO is not a suitable solvent for the successive alkylation, the product was extracted with pentane and used for the next reaction without any purification. Benzyl additions to α-aminoxylated isovaleraldehyde were examined (Table 1). While the lithium[9] and Grignard reagents gave the desired 1,2-diol in good dr, the yields were poor because of the rapid enolate formation (entries 1, 2). Addition of ZnBr2 did not improve the yield of the Grignard reaction (entry 3) while the addition of MnBr2 or the ate complex of MnCl2·2LiCl[10] increased the yield (entries 4, 5). Finally, in the presence of CeCl3·2LiCl, which favors addition of Grignard reagent to carbonyl compounds,[11] benzylmagnesium chloride gave the product in 77% yield and >99:1 dr (entry 6). Gratifyingly, in all the reactions the N-O bond is cleaved cleanly, which was previously accomplished by Cu (II) catalyzed procedure or catalytic hydrogenation.[7, 12]

Table 1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | BnMCl | Additive | Yield [%][d] | dr[e] |

| 1 | BnLi | - | 30 | 91:9 |

| 2 | BnMgCl | - | <15 | 93:7 |

|

| ||||

| 3 | ZnBr2 | <15 | 87:13 | |

| 4 | BnMgCl | MnBr2 | 62 | 95:5 |

| 5 | MnCl2·2LiCl | 48 | 96:4 | |

| 6 | CeCl3·2LiCl | 77 | >99:1 | |

10 mol% 1 used.

Pentane used for extraction.

5 equiv BnLi or BnMgCl and 5 equiv additive used.

Isolated yield of two diastereomers. Based on nitrosotoluene.

Determined by 1H NMR.

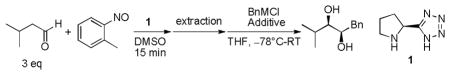

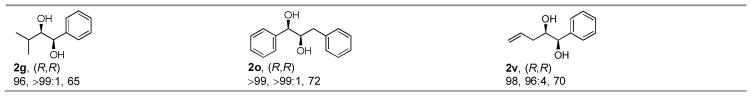

With the optimized procedure in hand, several aldehydes[13] and a wide range of Grignard reagents were examined using 1 or L-proline as the catalyst (Table 2). Not only tertiary alkyl Grignard reagents (2f, 2q) but also secondary (2e, 2p, 2u) and primary (2b–d, 2m–o, 2s, 2t) alkyl Grignard reagents gave the 1,2-diols in excellent dr. Even a small nucleophile, methylmagnesium chloride, produced the 1,2-diols (2a, 2l) in high dr. Aryl Grignard reagents also gave the products (2g–j, 2r, 2v) in good to excellent dr. Electron-withdrawing (2h) and donating groups (2i) on the phenyl ring were well tolerated. t-BuLi/CeCl3·2LiCl could also be used for the synthesis of 1,2-diols (2f, 2q), which in some cases (2f) provided better yields than t-BuMgCl/CeCl3·2LiCl. In addition, lithium t-butyl acetate gave the 1,2-diol (2k) in good dr and ee. The reactions involving 4-pentenal (2s–v) or allyl Grignard reagent (2c, 2n, 2s) gave the 1,2-diols with terminal olefin groups, which are complementary to Sharpless AD reactions. The ee’s of the diols are excellent, which we believe were completely transferred from the α-aminoxylated aldehydes.

Table 2.

|

R=Pri (2a–k), Ph (2l–r), allyl (2s–v).

10 mol% 1 or L-proline used.

5 equiv Grignard reagent and 5 equiv CeCl3·2LiCl used.

Absolute configuration determined by comparison of specific rotation.

dr determined by 1H NMR. Ratios in parentheses determined by GC.

Isolated yield of two diastereomers. Based on nitrosotoluene.

R’Li used instead of R’MgCl.

Arylmagnesium bromide used.

Grignard reagent reacted with CeCl3·2LiCl at RT.

The addition reaction warmed to 0°C.

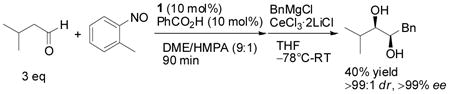

If necessary, the 1,2-diol can be synthesized in one pot. The aminoxylation of isovaleraldehyde was conducted in DME/HPMA (9:1),[14] and the mixture was exposed to benzyl Grignard reagent to give the desired product as single diastereomer in 40% yield and >99% ee [Eq. (3)].

|

(3) |

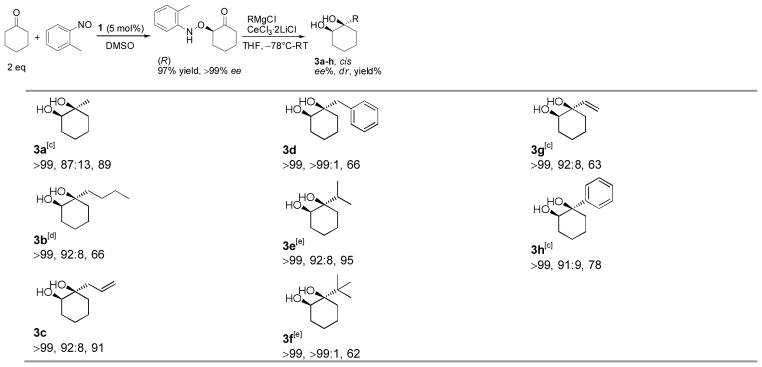

The carbonyl substrate is not limited to aldehyde. Aminoxylation of cyclohexanone with 2-nitrosotoluene gave the product in quantitative yield, which is better than that previously reported (77%).[7e] When subjected to CeCl3·2LiCl mediated Grignard reactions, the aminoxylation product gave the corresponding cis-1,2-diols in excellent dr, which makes the present procedure a suitable route to prepare a chiral quarternary carbon center (Table 3).[15] These diols are difficult to prepare in high ee by known methods.[4b]

Table 3.

|

cis configuration and dr determined by 1H NMR.

Isolated yield of two diastereomers. Based on aminoxylated cyclohexanone.

RMgBr used in the absence of CeCl3·2LiCl.

n-BuMgCl used in the absence of CeCl3·2LiCl.

RLi used instead of RMgCl.

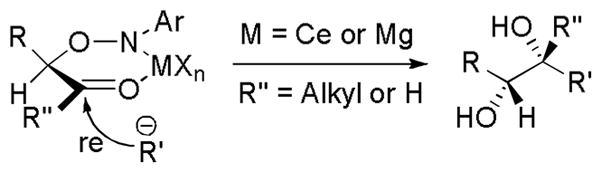

The observed excellent diastereoselectivities of the 1,2-diol synthesis can be explained as follows (Figure 1). Chelation of the aminoxylated aldehyde or ketone with MXn (M=Mg or Ce) will cause the metallated R’s pecies to approach the activated carbonyl group from the less hindered Re face, leading to the generation of the 1,2-diol. Single-electron transfer between the organometallic reagent and the aminoxylated aldehyde or ketone is believed to be the reason for the N-O bond cleavage: in the reactions using PhMgCl, biphenyl (50% yield) is separated, which is assumed to be formed from the coupling of phenyl radical.[16]

Figure 1.

Proposed transition state structure of the 1,2-diol synthesis.

In summary, we have opened a new asymmetric entry to 1,2-diols based on a completely different and flexible approach: using readily available carbonyl compounds and organometallic reagents as starting materials. The application of CeCl3·2LiCl is essential to obtain high overall yields and high dr (up to >99:1) of the 1,2-diol products. In comparison with traditional methods of 1,2-diol synthesis from alkene, our method eliminates the stereoselective preparation of alkene and overcomes the regioselectivity problem of oxidation. The method will be further extended to the preparation of various 1,2-difunctional compounds including N,O- and N,N-derivatives with high selectivities, which is ongoing in our laboratory.

Experimental Section

General procedure for 1,2-diol synthesis: A dry Schlenk tube was charged with 5-[(2S)-2-pyrrolidinyl]-1H-tetrazole (1) or L-proline (0.2 mmol), 2- nitrosotoluene (242 mg, 2.0 mmol) and DMSO or CHCl3 (3 mL). The aldehyde (6.0 mmol) was added in one portion via pipette. The mixture was stirred at the indicated temperature to give a clear solution (For temperature, solvent and reaction time, see Supporting Information). Cold water was added. The aqueous mixture was extracted with pentane or 1:1 pentane/Et2O (3 × 15 mL). The extracts were washed with H2O (30 mL), dried over 4 Å MS (5 g), and concentrated at 10–20°C. The resulting yellow oil was dried under high vacuum (5 min) and dissolved in THF (10 mL). The solution (5 mL) of the aminoxylated aldehyde (~1.0 mmol) was added via syringe to a cooled mixture of R’MgCl (5.0 mmol) and CeCl3·2LiCl (5.0 mmol) at −78°C. The mixture was allowed to warm to RT over a period of 5 h, and stirred at RT overnight. Saturated aqueous NH4Cl (10 mL) was added, followed by diluted hydrochloric acid (2 N, 4 mL). The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with AcOEt (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. The crude product was chromatographed on silica gel using 4:1 and then 2:1 hexanes/AcOEt as eluents. After concentration of the eluates, the yield of the 1,2-diol was determined and the syn:anti ratio analyzed by 1H NMR.

Footnotes

Financial support has been provided by NIH (5R01GM068433-06) and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.(a) Ohmori K, Mori K, Ishikawa Y, Tsuruta H, Kuwahara S, Harada N, Suzuki K. Angew Chem. 2004;116:3229–3233. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3167–3171. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fürstner A, Bogdanović B. Angew Chem. 1996;108:2582–2609. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1996;35:2442–2469. [Google Scholar]; c) Fu GC. Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. In: Otera J, editor. WILEY-VCH. Weinheim; Germany: 2000. pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Prasad KRK, Joshi NN. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:1957–1960. [Google Scholar]; b) Shindo M, Koga K, Tomioka K. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9351–9357. [Google Scholar]; c) Donnoli MI, Superchi S, Rosini C. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9392–9395. [Google Scholar]; d) Ishimaru K, Monda K, Yamamoto Y, Akiba K. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:727–734. [Google Scholar]; e) Ishihara K, Nakashima D, Hiraiwa Y, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:24–25. doi: 10.1021/ja021000x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Kim KS, Park JI, Ding P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:6471–6474. [Google Scholar]; b) Superchi S, Contursi M, Rosini C. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:11247–11254. [Google Scholar]; c) Tunge JA, Gately DA, Norton JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4520–4521. [Google Scholar]; d) Ray CA, Wallace TW, Ward RA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:3501–3504. [Google Scholar]; e) Andrus MB, Soma Sekhar BBV, Meredith EL, Dalley NK. Org Lett. 2000;2:3035–3037. doi: 10.1021/ol0002166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For asymmetric dihydroxylation of olefins, see: Jacobsen EN, Marko I, Mungall WS, Schroeder G, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:1968–1970.Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547.

- 5.For asymmetric epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins, see: Irie R, Noda K, Ito Y, Matsumoto N, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:7345–7348.Irie R, Noda K, Ito Y, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1055–1058.Zhang W, Loebach JL, Wilson SR, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2801–2803.Yang D, Yip Y, Tang M, Wong M, Zheng J, Cheung K. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:491–492.Yang D, Wang X, Wong M, Yip Y, Tang M. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11311–11312.Shi Y. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:488–496. doi: 10.1021/ar030063x.Hickey M, Goeddel D, Crane Z, Shi Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5794–5798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307548101.Barlan AU, Basak A, Yamamoto H. Angew Chem. 2006;118:5981–5984. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601742.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5849–5852. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601742.

- 6.For reviews of nitrosoaldol reaction, see: Merino P, Tejero T. Angew Chem. 2004;116:3055–3058.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2995–2997. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301760.Janey JM. Angew Chem. 2005;117:4364–4372.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4292–4300. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462314.Yamamoto H, Momiyama N. Chem Commun. 2005:3514–3525. doi: 10.1039/b503212c.Plietker B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3453–3459.

- 7.(a) Zhong G. Angew Chem. 2003;115:4379–4382. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:4247–4250. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brown SP, Brochu MP, Sinz CJ, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10808–10809. doi: 10.1021/ja037096s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hayashi Y, Yamaguchi J, Hibino K, Shoji M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:8293–8296. [Google Scholar]; d) Hayashi Y, Yamaguchi J, Sumiya T, Shoji M. Angew Chem. 2004;116:1132–1135. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:1112–1115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hayashi Y, Yamaguchi J, Sumiya T, Hibino K, Shoji M. J Org Chem. 2004;69:5966–5973. doi: 10.1021/jo049338s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Hayashi Y, Yamaguchi J, Hibino K, Sumiya T, Urushima T, Mitsuru S, Hashizume D, Koshino H. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:1435–1439. [Google Scholar]; g) Wang W, Wang J, Li H, Liao L. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7235–7238. [Google Scholar]; h) Momiyama N, Torii H, Saito S, Yamamoto H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5374–5378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307785101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detailed results will be published in due course.

- 9.For preparation of BnLi in THF, see: Gilman H, McNinch HA. J Org Chem. 1961;26:3723–3729.

- 10.Cahiez G, Alami M. Tetrahedron. 1989;45:4163–4176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krasovskiy A, Kopp F, Knochel P. Angew Chem. 2006;118:511–515. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:497–500. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502485. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momiyama N, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6038–6039. doi: 10.1021/ja0298702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phenylacetaldehyde and 4-pentenal were selected because few α-aminoxylations of them have been reported.

- 14.For reactions of different nitrosoarenes with isovaleraldehyde in DME and HMPA, see Supporting Information.

- 15.For absolute configuration of α-aminoxycyclohexanone, see Supporting Information.

- 16.For N-O bond cleavage by Grignard reagents, see: Wichterle O, Vogel J. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1949;14:209–218.Dinh TQ, Armstrong RW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:1161–1164.