Abstract

Parallel endografts (also known as snorkels or chimneys) are a proposed strategy for increasing the applicability of endovascular repair to aneurysms involving branch vessels. One major disadvantage of this strategy is the imperfect nature of seal inherent to having multiple side-by-side endografts. In this article, the use of odd-shaped parallel endografts to facilitate apposition and improve seal is proposed and a technique to mold a round stent graft into an “eye” shape using balloons is described.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, endovascular procedure, endovascular repair, aneurysm, snorkel, chimney, juxtarenal

The use of parallel endografts has become an increasingly popular adjuvant maneuver for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) with challenging anatomy. The method, commonly referred to as the snorkel or chimney technique, uses placement of one or more covered stents alongside the main endoprosthesis to maintain flow in branch vessels that have been intentionally covered to achieve additional seal for exclusion of the aneurysm. However, one of the weaknesses of this technique is the imperfect nature of the seal inherent to the multiple side-by-side grafts. The branch vessel graft (snorkel) interferes with apposition of the main endoprosthesis to the aortic wall, leading to gutters alongside the snorkel that could allow continued pressurization of the sac. The purpose of this study is to describe the use of odd-shaped parallel endografts to obliterate the gutters and present a method to mold currently available devices to improve seal in parallel configurations.

Method

“Eye of the Tiger” Technique

The “Eye of the Tiger” is a technique that can be used to transform a standard snorkel stent graft from a round shape into an “eye” or “football” shape, facilitating apposition against the aortic wall (Fig. 1). For this technique, a balloon expandable stent (e.g., iCAST, Atrium Medical, Hudson, New Hampshire) is required and should be sized according to its target branch vessel. Once placed, the portion of the stent that runs parallel to the aortic endoprosthesis should be greatly overexpanded. We prefer to use a 12-mm balloon for this. A bare stent (also sized to the target branch vessel) is then advanced inside the overexpanded portion of the snorkel, but not deployed. The parallel portion of the snorkel is then crushed against the aortic wall with an aortic balloon. The bare stent is then deployed, expanding only the central portion of the snorkel. When viewed on end, the combination resembles an eye with the bare stent maintaining the central lumen and the flared ends of the molded stent graft obliterating the gutters (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Two diagrams of a cross-sectional view of parallel endografts in an aortic lumen. On the left, a round snorkel graft (S) can make it difficult for the aortic endograft (AE) to appose the remaining inner surface of the aortic lumen, leading to gutters alongside the snorkel graft and potential endoleak (shown in red.) On the right, an eye-shaped snorkel graft (S) facilitates apposition of the aortic endograft (AE), minimizing the potential for endoleak.

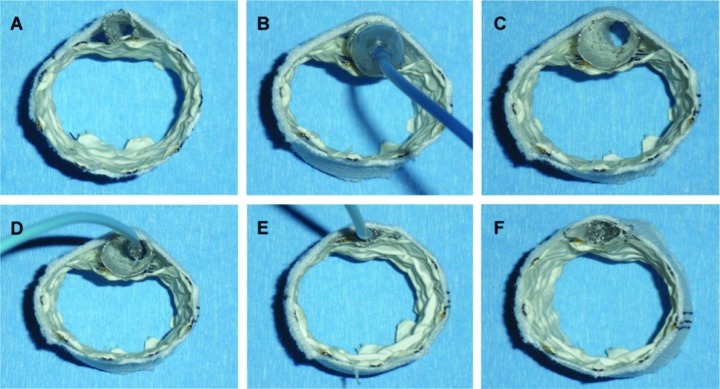

Figure 2.

Steps in performing the “Eye of the Tiger” molding technique to obliterate the gutters of parallel endografts. (A) A balloon expandable stent sized to the target vessel is used for the snorkel graft. (B and C) The parallel portion is then greatly overexpanded. (D) A bare metal stent sized to the target vessel is then advanced into the snorkel graft, but not yet deployed. (E) The snorkel graft is then flattened to achieve wall apposition. (F) The bare stent is then deployed to expand only the middle portion of the stent. The molded snorkel stent now takes the shape of an eye, which is an easier shape than a circle for the aortic endoprosthesis to conform against and obliterate the gutters.

Discussion

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has become a popular treatment for abdominal aortic aneurysms because of the decreased morbidity and early mortality associated with this method compared with open repair.1,2,3 However, both short- and long-term success with this technique requires the achievement of secure seal at the proximal and distal attachment sites. Therefore, patients with aneurysms involving or in close proximity to important branch vessels have traditionally been excluded from EVAR. Parallel endografting is one method proposed to extend the applicability of endovascular repair to these patients by taking advantage of seal zones that cross these branch vessels. The method is appealing because it uses off-the-shelf devices for immediate availability. Further, the modular nature of the technique enables potential applicability to almost any anatomy.

Unfortunately, as already described, the additional seal achieved in parallel endografting is imperfect. Success with this technique, therefore, will likely depend on strategies that overcome this flaw. One such strategy is to rely on achieving a ring of seal, or “gasket” seal, in the neck of the aneurysm outside the area of the parallel endografts.4 For juxtarenal aneurysms, this location would correspond to the infrarenal aorta. Obviously, some amount of neck would be needed for this strategy to work.

In patients with absolutely no neck, the use of long overlap zones has been proposed as a potential strategy to nullify the gutter effect. Length increases resistance to flow through the gutters. Coupled with the relatively small lumen of the gutters, this promotes thrombosis and seal. The exact amount of length necessary to promote thrombosis has not been determined. Kolvenbach et al recently suggested a length of 5 cm.5 However, this was based on a preliminary experience of only five cases. Still, this appears to be a reasonable recommendation at present.

The disadvantage of using long overlap zones is that it can lead to coverage of both additional branches (requiring additional snorkels) and intercostal arteries (increasing the chance of spinal cord ischemia). Further, it increases the resistance in the snorkel grafts as well, thereby potentially increasing their thrombosis risk.

Direct obliteration of the gutters is therefore a more attractive option. While some have suggested this can be achieved by grossly oversizing the aortic endograft to force it to wrap around the smaller endograft, our experience has not corroborated this. Current aortic endografts are simply not designed to asymmetrically expand and fill crevices around the outside of a small tubular structure. A more likely scenario is that the graft will remain fairly symmetrically compressed or infold.

Therefore, it is our contention that the smaller endograft (i.e., the snorkel) is a better candidate to use to obliterate the gutters. When using parallel endografts, the natural shape of the region of poor apposition is a fat crescent, or “eye” shape. Accordingly, using a snorkel with this shape instead of a round one should facilitate full apposition. The “Eye of the Tiger” maneuver allows one to mold a standard round stent to this shape to potentially improve success with parallel endografts in patients with no traditional neck using shorter overlap zones (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Luminal view from a postoperative three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction of a molded snorkel graft using the “Eye of the Tiger” technique for branch vessel preservation during aortic endografting. Note the oblong shape obliterates the gutters and facilitates apposition of the aortic endograft.

Admittedly, there are disadvantages to this maneuver. First, it adds to both the expense and complexity of a procedure that is not lacking in either. Perhaps more importantly, though, we have experienced difficulties in getting balloon expandable stent grafts to conform to the sharp angles that often need to be negotiated in these configurations. The stiffness of these stents can displace the aortic endograft off the vessel wall as the snorkel protrudes into the lumen rather than conform to the vessel wall in a parallel course to the aortic stent. This displacement can be minimized by using low inflation pressures (less than 4 atm) during the final angioplasty of the parallel stents, but the decreased flexibility of currently available balloon expandable stent grafts remains a drawback to this technique. Ultimately, the widespread use of parallel endografts to treat extremely complex anatomy may depend on the development of more flexible odd-shaped stent grafts.

Our early experience has yielded technical success of achieving intraoperative seal in eight patients that otherwise would have lacked a traditional seal zone if parallel endografts had not been used. Initial postoperative computed tomography scans confirmed no type I endoleaks, but there was displacement of the stent off the vessel wall in one patient due to conformability issues as described above, prompting us to use lower inflation pressures when molding the parallel grafts and to favor the use of this technique in straight anatomy. Obviously, further studies with longer follow-up period will be necessary to determine the durability of this technique.

In conclusion, we present a technique to mold a parallel endograft into an oblong or “eye” shape. The molding helps facilitate the apposition of the two parallel endografts to seal the aortic lumen and obliterate the gutters that could lead to endoleak in these cases. We believe the technique may improve the results of parallel endografting for branch vessel preservation during EVAR with challenging anatomy.

Note

This work was presented at the International College of Angiology, 52nd Annual World Congress, Lexington, Kentucky, USA October 19, 2010.

References

- 1.Blankensteijn J D, de Jong S E, Prinssen M. et al. Dutch Randomized Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) Trial Group . Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(23):2398–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EVAR trial participants . Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9478):2179–2186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lederle F A, Freischlag J A, Kyriakides T C. et al. Open Versus Endovascular Repair (OVER) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group . Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1535–1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin Z K, Chuter T A, Hiramoto J S, Reilly L M, Schneider D B. Double-barrel technique for preservation of aortic arch branches during thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22(6):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolvenbach R R, Yoshida R, Pinter L, Zhu Y, Lin F. Urgent endovascular treatment of thoraco-abdominal aneurysms using a sandwich technique and chimney grafts—a technical description. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]