Abstract

Background

To date, no standardized presentation format is taught to emergency medicine (EM) residents during patient handoffs to consulting or admitting physicians. The Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) is a common format that provides a consistent framework to communicate pertinent information.

Objective

The objective of this study was to describe and evaluate the feasibility of using SBAR to teach interphysician communication skills to first-year EM residents to use during patient handoffs.

Methods

An educational study was designed as part of a pilot curriculum to teach first-year EM residents handoff communication skills. A standardized SBAR reporting format was taught during a 1-hour didactic intervention. All residents were evaluated using pretest/posttest simulated cases using a 17-item SBAR checklist initially, and then within 4 months to assess retention of the tool. A survey was distributed to determine resident perceptions of the training and potential clinical utility.

Results

There was a statistically significant improvement from the resident scores on the pretest/posttest of the first case (P = .001), but there was no difference between posttest of the first case and pretest of the second case (P = .34), suggesting retention of the material. There was a statistically significant improvement from the pretest and posttest scores on the second case (P = .001). The survey yielded good reliability for both sessions (Cronbach alpha = 0.87 and 0.89, respectively), demonstrating statistically significant increases for the perceived quality of training, presentation comfort level, and the use of SBAR (P = .001).

Conclusion

SBAR was acceptable to first-year EM residents, with improvements in both the ability to apply SBAR to simulated case presentations and retention at a follow-up session. This format was feasible to use as a training method and was well received by our resident physicians. Future research will be useful in examining the general applicability of the SBAR model for interphysician communications in the clinical environment and residency training programs.

Editor's note: The online version of this article contains the SBAR Physician to Physician Report Checklist (29KB, doc) , as well as 2 pretest cases (1 (28KB, doc) , 2 (28.5KB, doc) ) and 2 posttest cases (1 (29KB, doc) , 2 (27.5KB, doc) ) used in this study.

What is known

There is no universally taught, standardized presentation format for emergency medicine residents to use for patient handoffs.

What is new

A situation-background-assessment-recommendation (SBAR) format provides a consistent framework for residents to communicate pertinent information during handoffs.

Limitations

Data collection in a simulated, single-site setting with a small sample (25 residents) limits generalizability; possible reviewer bias, and limited evidence-based support of SBAR in the context of handoffs.

Bottom line

This feasible training method yielded statistically significant improvement in residents' application of SBAR to simulated case presentations and retention at a follow-up session.

Introduction

In recent years, the importance of communication in the transition of patient care between health care providers has been an important issue addressed by the Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.1–5 One area of communication that has received much attention is handoffs, also referred to as “transitions of care” or “sign-outs,” which are a transfer of responsibility between physicians on both the presenting and receiving ends of a patient's care.2–4 Patient handoffs are a complex process affected by multiple variables and have a potential for error, especially with interprovider communication.3,6–8 Yet, the process of teaching physician handoffs between specialties is not well described in the emergency medicine (EM) literature.6,9–12 No best practice recommendations exist and there is no universally taught, standardized handoff format that emergency physicians use for patient care.10

Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) provides a framework for effective communication among members of the health care team.12 Multiple articles have described use of the SBAR tool, most commonly in the nursing literature.12–17 We describe and evaluate the feasibility of a pilot SBAR training program to teach interphysician communication skills for first-year EM residents to use with patient handoffs.

Methods

During the 2008–2011 academic years, all 25 EM first-year residents entering the program participated in the training. The study used a pretest and posttest design. Each case was presented in the traditional EM oral board certification examination format by a board-certified EM faculty member (M.C.T. or J.M.L.). Before each case, residents were given instructions regarding the format. The cases were developed by the authors for the common chief complaints of chest pain and abdominal pain using presentations of acute myocardial infarction, thoracic aortic dissection, ectopic pregnancy, and appendicitis.

Because the goal was to evaluate residents' case presentation skills (not their clinical knowledge or management skills), the examiner conveyed all critical case information during each scenario. The examiner then evaluated the resident's verbal presentation using a standardized 17-item SBAR checklist the authors adapted from other examples.13 The checklist included items agreed to be commonly relayed and clinically pertinent for a complete handoff, and it is provided as online supplemental content. Residents were scored on an all-or-nothing basis on each item that represents typical information requested during a case presentation. Excluding case development, the time commitment per year for the 2 faculty members was less than 10 hours each.

Pretest

The first SBAR session (session A) occurred during our July first-year resident orientation. Each resident was individually presented a case. After data gathering, the resident then presented the case to the examiner. Residents then received a 1-hour lecture on patient safety, approaches for presenting cases to consultants, and the SBAR model. Each resident then was given a second (posttest) case, which they presented to the alternate reviewer.

Following the session, residents were given an SBAR pocket card with the checklist items and instructions, and an SBAR worksheet to complete in the clinical setting prior to case presentations. Residents then proceeded with their scheduled off-service rotations, with 2 to 3 returning each month for their next emergency department rotation.

Posttest

Upon returning to the emergency department, residents were scheduled for session B without being told its purpose. Residents were given and presented a case for evaluation, followed by a brief review of SBAR and its clinical application. Residents were then given a second case to present, which was evaluated in the same manner as previous cases.

Survey

At the end of each session, residents completed a survey developed by the authors that asked them to rate various aspects of the training and the SBAR tool. A priori power analysis revealed that a statistical power of 0.92 would be achieved for a sample size of N = 25 and a mean difference of 2 points on the SBAR checklist.

Data Analysis

We scored the case presentations by giving 1 point for each correctly presented item (for a total of 17 points). The mean scores before and after training were compared for sessions A and B using parametric tests. The mean posttraining score from session A was also compared to the pretraining score from session B in order to measure knowledge retention. Each component of SBAR was also analyzed separately. The survey responses were analyzed with nonparametric tests. All data were analyzed with SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

The Medical College of Wisconsin's Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

Results

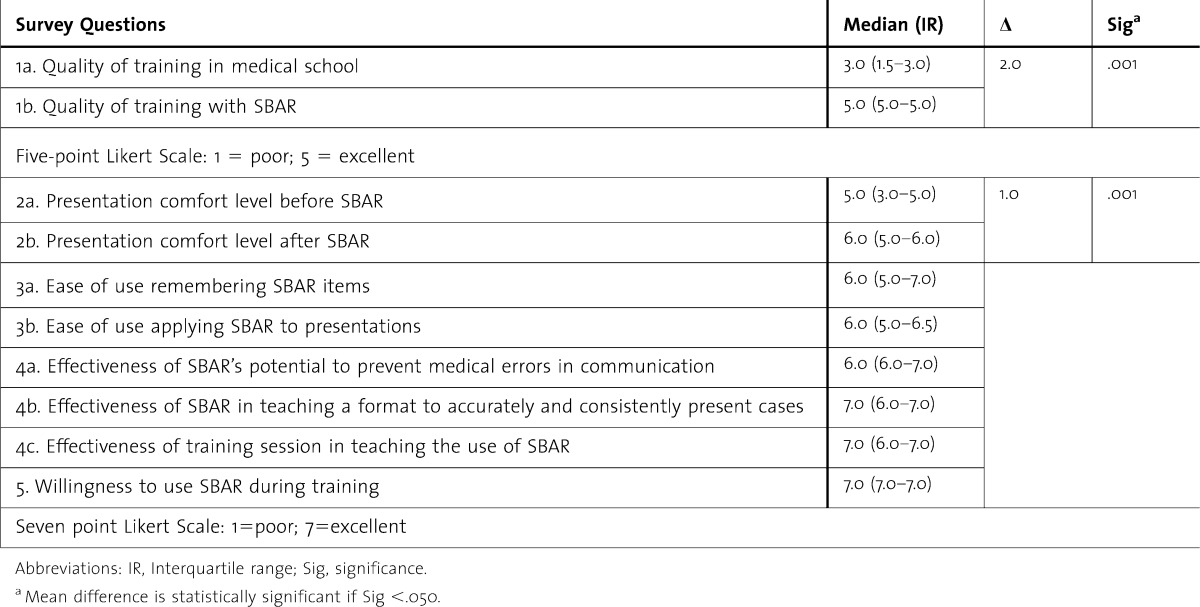

We used repeated-measures analysis of variance to detect differences in scores for pretests and posttests in both sessions. Mauchly test of sphericity was P = .16 with sphericity of data assumed and no corrections needed. The findings showed an overall statistically significant difference in mean scores (P = .001) with pairwise differences revealed through Bonferroni t tests (table 1). For session A there was a statistically significant improvement in resident posttraining scores (mean, 15; SD, 1.6) compared with pretraining scores (mean, 10.2; SD, 2.7; P = .001). There was no statistically significant difference in posttraining session A and pretraining session B scores (P = .34), suggesting retention of the use of the tool. In session B, there was statistically significant improvement from the pretraining to the posttraining scores (mean, 14.4; SD, 2.2 versus mean, 16.3; SD, 1.6; P = .001) for all 3 years (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Pretest and Posttest Retention Scores for First-Year Emergency Medicine Residentsa

When the components of SBAR were analyzed separately, the results were similar to the aggregate scores.

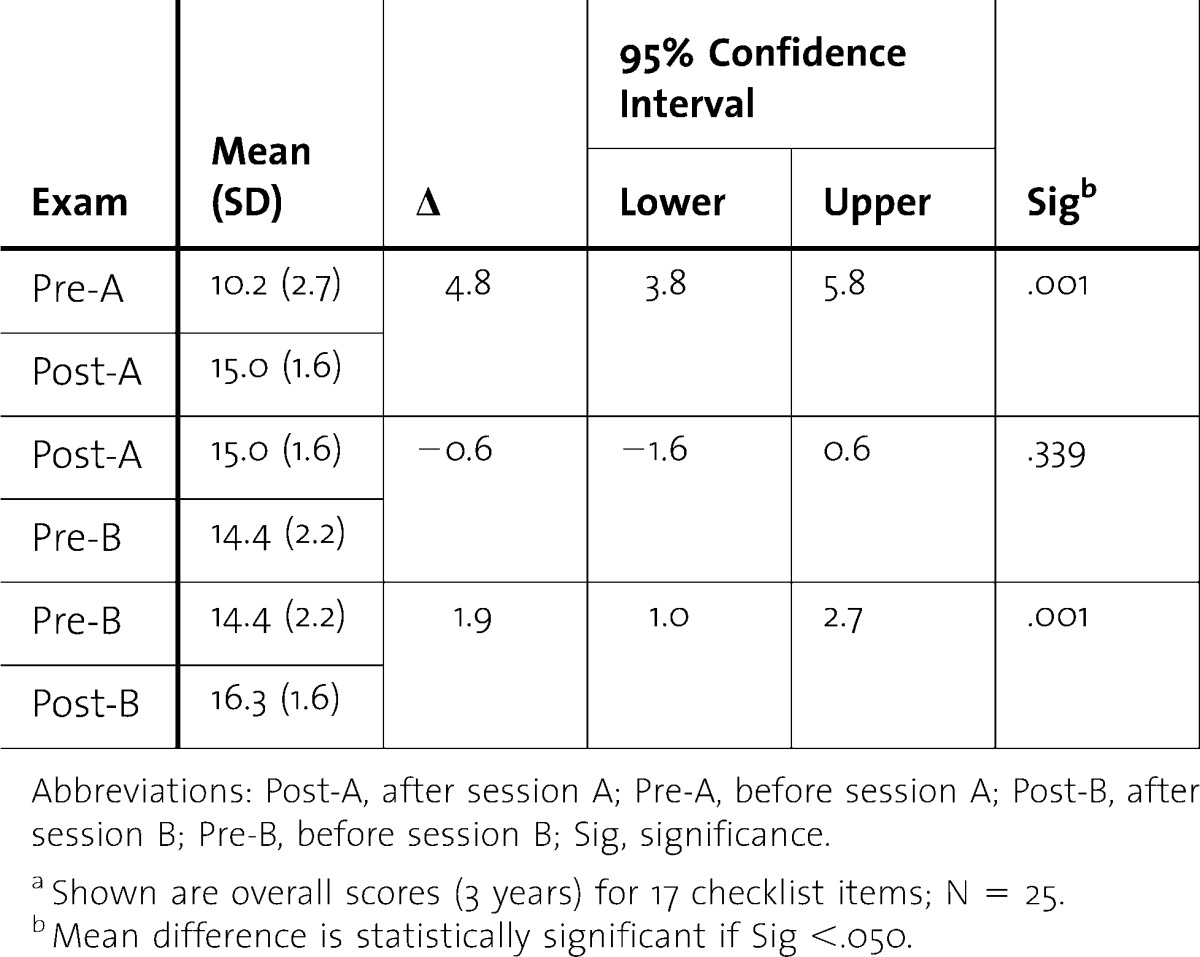

The results of our survey are shown in table 2. Residents' responses suggested their handoff and communication training during medical school was variable, and they favored our SBAR training over their medical school experience (P = .001). Residents also gave high ratings to the effectiveness of the session (6.5 out of 7) and their willingness to use SBAR (6.8). Finally, there was a statistically significant improvement (P < .001) in the residents' perception of their ability to effectively communicate organized information using SBAR.

TABLE 2.

Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation (SBAR) Survey for First-Year Emergency Medicine Residents (N = 25)

Discussion

We found that the SBAR was acceptable to first-year EM residents, with statistically significant improvements in their ability to apply SBAR to simulated case presentations. There was no difference in scores between sessions A and B, suggesting that the material was learned and retained. Residents also rated the overall usefulness of the curriculum highly, even in comparison with previous educational experiences. This format was feasible for faculty to use as a training method and was well received by our resident physicians.

Studies have shown that physicians often fall back on their personal preferences for format and language, adding additional layers of complexity that the receiver must interpret.4,18 To date, the SBAR approach is the most commonly used approach for improving clinical case communications, and we found it more adaptable to the emergency department environment than other, more complex models.19–20 Notably, we found this format conducive to training first-year EM residents in handoff communications.10,16

Limitations of our study include gathering data in a simulated setting. Our future goal would be to examine patient presentations in the emergency department. Additionally, we only used 2 reviewers and 25 residents during a 3-year period in a single residency program, limiting the generalizability of our findings. The fact that the reviewers were responsible for teaching the model potentially introduced bias. There was no “gold standard” to which to compare SBAR given the lack of literature on this subject when we began, and improvement could have been due to exposure and repetition.

Conclusion

The use of SBAR is feasible for interphysician resident communication training. The curriculum has been well received by our residents and has become our department standard for presentations by all physicians, residents, and nonphysician providers. Future research will be useful in examining the general applicability of the SBAR model for interphysician communications in the clinical environment and other residency training programs.

Footnotes

All authors are at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Matthew C. Tews, DO, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine; J. Marc Liu, MD, MPH, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine; and Robert Treat, PhD, is a Senior Educational Evaluator and Psychometrician in the Office of Educational Services.

References

- 1.WHO Collaborating Centre for Patient Safety Solutions. Communication during patient handovers. Patient Saf Solutions. 2007:1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rider EA, Keefer CH. Communication skills competencies: definitions and a teaching toolbox. Med Educ. 2006;40:624–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horwitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, Shah NR, Kulkarni RG, Jenq GY. Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:701–10.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung DS, Kelly JJ, Beach C, Berkeley RP, Bitterman RA, Broida RI, et al. Improving handoffs in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Joint Commission. National patient safety goals. http://www.jointcommission.org/patientsafety/nationalpatientsafetygoals/. Accessed February 26, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apker J, Mallak LA, Gibson SC. Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:884–894. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, Frankel RM. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2005;80:1094–1099. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson ES. Structuring flexibility: the potential good, bad and ugly in standardisation of handovers. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:4–5. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.022772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz LI, Krumholz HM, Green ML, Huot SJ. Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1173–1177. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.11.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Little BW. Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:196–204. doi: 10.1177/1062860609332512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beach C, Croskerry P, Shapiro M Center for Safety in Emergency Care. Profiles in patient safety: emergency care transitions. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha M, Shriki J, Salness R, Blackburn PA. Need for standardized sign-out in the emergency department: a survey of emergency medicine residency and pediatric emergency medicine fellowship program directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:192–196. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bello J, Quinn P, Horrell L. Maintaining patient safety through innovation: an electronic SBAR communication tool. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011;29:481–483. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31822ea44d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boaro N, Fancott C, Baker R, Velji K, Andreoli A. Using SBAR to improve communication in interprofessional rehabilitation teams. J Interprof Care. 2010;24:111–114. doi: 10.3109/13561820902881601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunsford J. Structured communication: improving patient safety with SBAR. Nurs Womens Health. 2009;13:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2009.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodhall LJ, Vertacnik L, McLaughlin M. Implementation of the SBAR communication technique in a tertiary center. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green EH, Hershman W, DeCherrie L, Greenwald J, Torres-Finnerty N, Wahi-Gururaj S. Developing and implementing universal guidelines for oral patient presentation skills. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:263–267. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1703_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green EH, Decherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe BA, Hershman W. The oral case presentation: what internal medicine clinician-teachers expect from clinical clerks. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:58–61. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.536894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills: a rhetorical analysis with pedagogical and professional implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:308–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]