The Challenge

As medicine strives to address social determinants of health to eliminate health disparities and improve health outcomes, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education scholarship requirement presents an opportunity for residents to apply systematic inquiry to community-identified problems. Trainees are expected to engage in scholarship, and this framework can be applied in a community setting, and can take into account the participatory nature, purpose, and unique challenges of community-engaged work.

What Is Known

Broadened definitions of scholarship and application of the Glassick criteria1 beyond traditional research have promoted systematic inquiry in the context of health care systems, such as clinical practice, teaching, and quality improvement. This has expanded the ways in which trainees can apply a scholarly approach.2 Community-engaged scholarship involves trainees in a mutually beneficial relationship with the community, and often combines aspects of other types of scholarship, including teaching and research, with community service and action. It entails participatory decision making, bidirectional learning, and contribution by both the academic and community partners at each step of the process.3,4

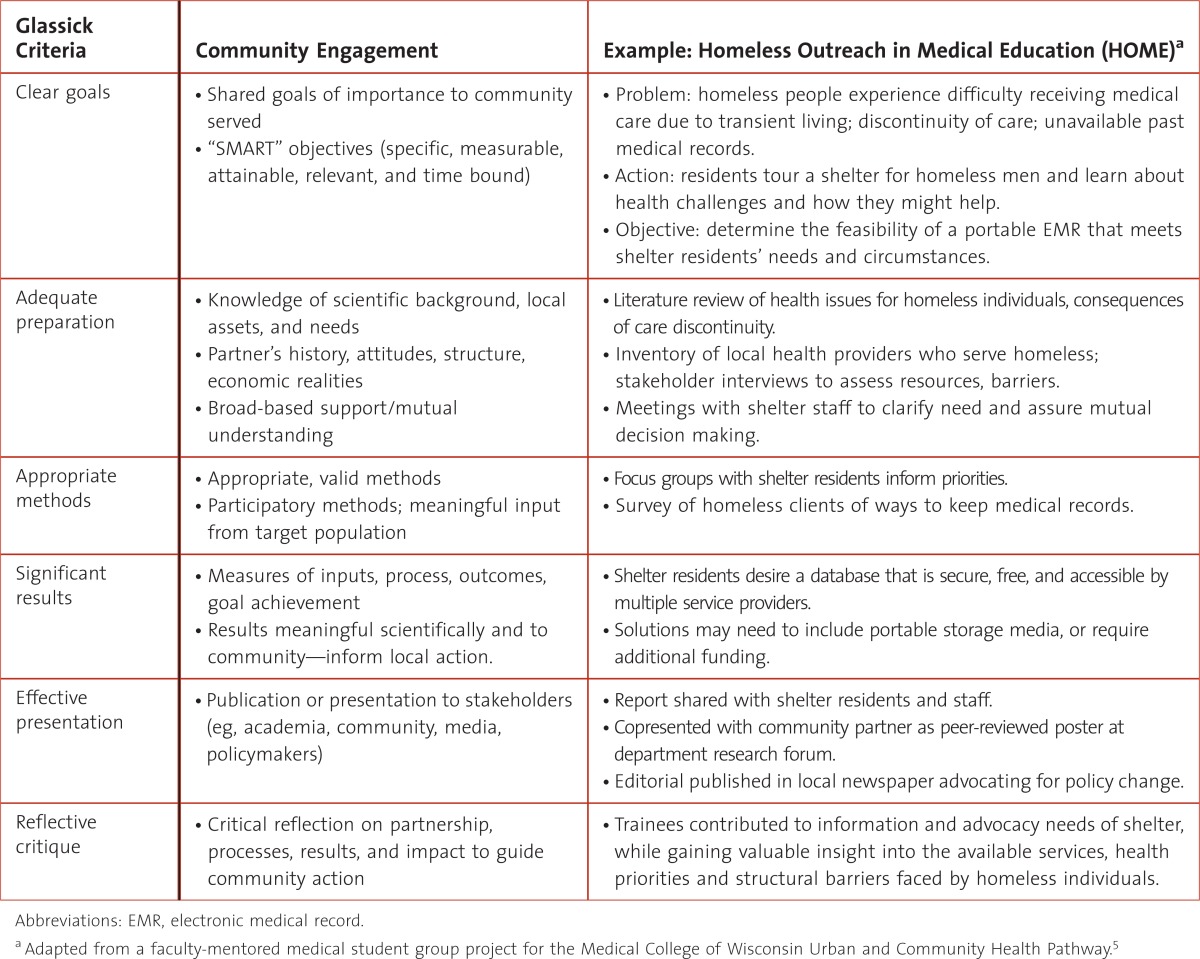

The Glassick criteria applied to community-engaged scholarship (Table) are as follows.

TABLE.

Glassick's Criteria Applied to Community-Engaged Scholarship

Clear Goals: To ensure that residents' scholarship meets expectations for community engagement, the project must emphasize shared goals that are oriented to the partner agency's mission and resources and to the needs and priorities of the community served.

Appropriate Preparation: Residents should develop adequate background knowledge through literature review and consultation with experts in content, methods, and community context. Time is needed for trust and relationship building, and to develop broad-based support for the work to be done.

Appropriate Methods: Participatory methods must be aligned with goals, feasible, ethical, and culturally appropriate. Input from the target populations ensures that methods are relevant and acceptable for accessing meaningful data for their community.

Significant Results: In addition to the magnitude or statistical power of the results, significance refers to the importance and meaningfulness of the findings to key stakeholders, and the findings' utility to inform action or policy. Community-engaged scholarship results are often most meaningful locally, and not easily generalized. As experts of their own context, community members contribute to the interpretation of the results.

Effective Presentation: Peer-reviewed products can be shared through scientific journals, professional meetings, or electronic repositories (eg, http://www.ces4health.info/, accessed July 17, 2012). Communities may share results with their members through meetings, reports, newsletters, media and action.

Reflective Critique: Community-engaged scholarship lends itself well to reflection at many levels: (1) results, in the context of community and existing literature; (2) the participatory process, and the richness and challenges of the relationships built; and (3) impact on learning, including the ability to combine knowledge with action to address social determinants of health in individuals and community.

How Can You Start TODAY

Program Director and Faculty:

Familiarize residents and faculty with the resources available through the Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/)

and help residents engaged in community service projects frame their work in terms of the Glassick criteria to raise the project rigor to a level of systematic inquiry that meets your scholarship requirements.

Residents:

Identify a local community agency that addresses a health issue of importance to you. Meet with agency staff to learn about their organization, mission, and community served. Discover how you might contribute to their mission while learning about the social factors underlying health disparities. Seek scholarly opportunities that have mutual benefit to you and to the community served.

What You Can Do LONG TERM

Partner with local community agencies to develop service-learning opportunities that meet your scholarly project requirement and community-identified needs. Incorporate community-engaged scholarship principles in grand rounds and didactic presentations. Provide time and flexibility in residents' schedules to meet the demands of building community-academic partnerships.

Footnotes

Linda N. Meurer, MD, MPH, is Professor, Family & Community Medicine, and Director, Academic Fellowship in Primary Care/Community-Based Research, and Urban and Community Pathway at the Medical College of Wisconsin; and Sabina Diehr, MD, is Associate Professor in Family & Community Medicine and Faculty Mentor for the Homeless Outreach in Medical Education (HOME) Project at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Funding: Work was partially supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, grant No. D56HP10304; and the Educational Leadership for the Health of the Public-Research and Education Initiative Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Resources

- 1.Glassick CE, Huber MT, Maeroff GI. Scholarship Assessed: Evaluation of the Professoriate. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson DE, Meurer LN, Braza D. Meeting the scholarly project requirement—application of Glassick's criteria beyond research. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):111–112. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00310.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calleson DC, Jordan C, Seifer SD. Community-engaged scholarship: is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise. Acad Med. 2005;80:317–321. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Community-engaged scholarship. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH) website. http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/scholarship.html. Accessed July 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meurer LN, Young S, Meurer JR, Johnson S, Gilbert I, Diehr S. The urban and community health pathway: preparing socially responsive physicians through community-engaged learning. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 suppl 3):S228–S236. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]