Abstract

Photorhabdus luminescens is a symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes. Analysis of the genome sequence of this organism revealed a homologue of PhoP-PhoQ, a two-component system associated with virulence in intracellular bacterial pathogens. This organism was shown to respond to the availability of environmental magnesium. A mutant with a knockout mutation in the regulatory component of this system (phoP) had no obvious growth defect. It was, however, more motile and more sensitive to antimicrobial peptides than its wild-type parent. Remarkably, the mutation eliminated virulence in an insect model. No insect mortality was observed after injection of a large number of the phoP bacteria, while very small amounts of parental cells killed insect larvae in less than 48 h. At the molecular level, the PhoPQ system mediated Mg2+-dependent modifications in lipopolysaccharides and controlled a locus (pbgPE) required for incorporation of 4-aminoarabinose into lipid A. Mg2+-regulated gene expression of pbgP1 was absent in the mutant and was restored when phoPQ was complemented in trans. This finding highlights the essential role played by PhoPQ in the virulence of an entomopathogen.

Pathogens have to overcome the defenses of their hosts. Photorhabdus luminescens, an insect pathogen, faces particularly challenging conditions. This bacterium has a complex life cycle that involves two completely different environments: a symbiotic stage, in which bacteria colonize the nematode gut, and a pathogenic stage, in which susceptible insects are killed by the combined action of the nematode and the bacteria. After entering the insect host, a nematode releases its bacterial symbionts into the insect hemocoel. Once released, the bacteria proliferate rapidly, disregarding both the humoral insect immune response (e.g., antibacterial peptides) and the cell-mediated insect immune response (hemocytes) (14, 17). While multiplying, the bacteria produce exo- and endotoxins, to which the insect succumbs within 48 h of infection. They also produce antibiotics that inhibit the growth of competing microorganisms in the insect cadaver (16, 57) and enhance conditions for nematode reproduction by providing nutrients and other growth factors utilized by the nematodes (25).

How the infecting bacteria overcome or escape from the insect immune system is still largely an open question. The recent sequencing of the strain TT01 genome revealed a plethora of candidate virulence factors (18). Some of these factors have previously been found to be involved in processes that result in insect death. The Mcf toxin (makes caterpillars floppy) was shown to be a dominant virulence factor critical for pathogenesis. The putative apoptosis action of this toxin in insect cells caused the larvae to loose body turgor and die (15). Purified high-molecular-weight toxin complexes had both oral and injectable activities with specific effects on the midgut epithelium of a wide range of insects (7, 70). The protease and lipase fractions did not significantly affect mortality rates (8, 68), while the role of purified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in virulence was uncertain (19). Recently, phlA, a locus encoding a hemolysin belonging to the two-partner secretion family of proteins, was identified in the TT01 genome. Although PhlA appears to be produced in the hemolymph during insect infection, the high virulence of a phlA mutant indicates that this hemolysin is not a major virulence determinant (9).

To colonize the nematode gut and multiply in the insect hemocoel (two environments whose physical and chemical properties differ), P. luminescens, like other bacterial pathogens (36), has evolved two-component signal transduction systems (66). These systems comprise a membrane-associated sensor kinase and a cytoplasmic transcriptional regulator. In response to an external stimulus, the sensor component autophosphorylates at a conserved histidine residue in an ATP-dependent reaction. In the second step, the phosphoryl group is transferred to the regulator component, promoting its binding to DNA. The two-component PhoP-PhoQ system has been found in many gram-negative bacteria (30), and its primary function seems to be control of physiological adaptation to Mg2+ availability (26). Mg2+ (or Ca2+) binding to the periplasmic domain of PhoQ promotes the dephosphorylation of phospho-PhoP. Expression of PhoP-activated genes is induced when the Mg2+ concentration is low (micromolar) and is repressed when the Mg2+ concentration is high (millimolar) (26, 27).

In spite of its presence in both pathogenic and nonpathogenic species, PhoP-PhoQ is an important regulator of virulence genes in a number of intracellular bacterial pathogens, including Salmonella sp., Shigella sp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Neisseria meningitidis (38, 45, 46, 52) This system has been studied extensively in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which it regulates directly or indirectly more than 40 different genes (29, 44, 65). Many of these genes are species specific and confer unique properties to the microorganism, including survival within macrophages, resistance to host antimicrobial peptides (APs) and acidic pH, invasion of epithelial cells, and antigen presentation (31, 45, 50, 51). These properties are often linked to modifications of many components in the bacterial cell envelope governed by PhoP-PhoQ (22, 32, 43, 51).

In an attempt to identify some of the regulatory systems involved in pathogenicity control in P. luminescens, we investigated the role of the PhoP-PhoQ homologue. A knockout mutant with a mutation in the phoP regulator was generated. The mutation affected several components of the bacterial envelope and, remarkably, resulted in an avirulence phenotype in an insect model, Spodoptera littoralis. Our results suggest that PhoPQ may sense conditions in the insect hemocoel and subsequently promote resistance to the innate immunity of the insect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Permanent stocks of all strains were maintained at −80°C in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with glycerol. P. luminescens was grown at 30°C. The P. luminescens strains used were TT01 (23) and its phoP derivative PL2104 (this study). The Escherichia coli strains used were TG1 (59) for plasmid maintenance and S17-1 (61) for conjugation. E. coli strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C, whereas P. luminescens strains were grown at 30°C in Schneider medium (BioWhittaker). To study the effects of Mg2+ concentration, ED*-glucose defined medium [15 mM NH4Cl, 11 μg of ferric citrate per ml, 0.4% glucose, 2 mM K2SO4, 80 mM K2HPO4, 44 mM KH2PO4, 3.4 mM Na3-citrate, 50 μM FeCl3, 7.5 μM MnCl2, 12.5 μM ZnCl2, 2.5 μM CuCl2, 2.5 μM CoCl2, 2.5 μM Na2MoO4] containing 20 μM MgCl2 (low-Mg2+ medium) or 10 mM MgCl2 (high-Mg2+ medium) was used for both E. coli and P. luminescens. The final concentrations of the antibiotics used for selection were as follows: 30 mg of gentamicin per liter, 20 mg of kanamycin per liter, and 20 mg of chloramphenicol per liter for E. coli; and 15 mg of chloramphenicol per liter for P. luminescens. All experiments were performed in accordance with the European regulation requirements concerning the contained use of group I genetically modified organisms (agreement no. 2736 CAII).

DNA manipulations and plasmid construction.

Chromosomal DNA preparation, ligation, E. coli electroporation, and Southern blotting were carried out by using standard procedures (59). Plasmid DNA was isolated with a GenElute plamid miniprep kit (Sigma). Restriction enzymes were obtained from Roche, and enzymatic reaction products were purified with a MinElute reaction cleanup kit (Qiagen).

Plasmid pDIA604 was constructed by two steps of PCR amplification. Briefly, the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene of pACYC184 (Biolabs) was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides Cat5 (5′-TTGATCGGCACGTAAGAGGT-3′) and Cat3 (5′-AATTTCTGCCATTCATCCGC-3′), which resulted in an 850-bp DNA fragment. Two 1.1-kb DNA fragments containing either the 5′ upstream region of phoP or the end of the coding region of phoP and the downstream region were also generated by PCR by using either oligonucleotides phoP3 (5′-AAACTGCAGCTCACCGGATGGAACGCCAG-3′) and phoP4 (5′-ACCTCTTACGTGCCGATCAAGGATCCGGTGTCACGAAGCTGTACC-3′) or oligonucleotides phoP5 (5′-GCGGATGAATGGCAGAAATTGGATCCCGATGCTGAACTGCGCGAA-3′) and phoP6 (5′-GCTCTAGAGCGCATACTGGCACGATGCAG-3′) and genomic DNA from P. luminescens TT01. The first 20 bases of primers phoP4 and phoP5 are complementary to primers Cat5 and Cat3, respectively. After purification with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), 100-ng portions of the three previously amplified fragments were mixed and used as a template to generate a new 3.1-kb DNA fragment by a second PCR performed with oligonucleotides phoP3 and phoP6. The resulting amplicon, which corresponded to a phoP::Cm fragment, was purified, restricted with PstI and XbaI, and ligated to the pJQ200KS vector (53) to obtain pDIA604.

Plasmid pDIA605 was constructed by cloning into the multiple cloning site of the pBluescript SK plasmid (Stratagene), restricted at PstI and XbaI sites, the previously amplified 3.1-kb phoP::Cm DNA fragment containing the phoP promoter region and the beginning of the phoP coding sequence.

To construct the pDIA607 plasmid, a DNA fragment containing the whole phoPQ locus was generated by PCR with primers PhoP1 (5′-AAACTGCAGATTGAAAGCCATGACGCCAG-3′) and PhoQ2 (5′-TGCTCTAGACATCCTGAGTGTGAAGTGAA-3′). The 2.5-kb amplified fragment was purified, restricted with XbaI and PstI (underlined sites), and cloned into the pBBR1MCS-5 vector, a low-copy-number mobilizable plasmid (40). The exact DNA sequence of pDIA606 was confirmed by sequencing (GENOME express, Montreoil, France).

Construction of a phoP mutant and complementation of the mutant.

Strain PL2104 was created by allelic exchange with pDIA604 (which contains a cat cassette in the phoP coding region). pDIA604 was transformed into E. coli S17-1 and introduced into P. luminescens by mating. Cmr Gms Sacr exconjugants were selected on proteose peptone agar (1% proteose peptone, 0.5% NaCl, 0.5% yeast extract, 1.5% agar) containing 2% sucrose. The exconjugants had undergone allelic exchange and lost the wild-type copy of phoP and the plasmid vehicle. Insertions were confirmed by Southern blot hybridization (data not shown) by using a PCR-amplified digoxigenin-labeled phoP gene probe, oligonucleotides phoP3 and phoP4, and a PCR digoxigenin probe synthesis kit (Roche).

Complementation was performed by using mating experiments. pDIA607 was used to transfer the phoPQ operon from E. coli S17-1 into the recipient P. luminescens PL2104. Cmr Gmr exconjugants containing the pDIA607 vector were selected.

Swimming capacity.

Tryptone motility plates containing 1% Bacto Tryptone (Difco), 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% Bacto Agar (Difco) were used to test bacterial motility as previously described (5).

In vivo pathogenicity assays.

The pathogenicity assays were performed with the common cutworm S. littoralis as previously described (28). Briefly, 20 μl of exponentially growing bacteria diluted in phosphate-buffered saline was injected into the hemolymph of 20 fifth-instar larvae of S. littoralis reared on an artificial diet. The insect larvae were then individually incubated at 23°C for up to 115 h, and bacterial CFU were determined by plating dilutions on Luria-Bertani agar. Insect death was monitored several times after injection. Three independent experiments were performed.

Antibacterial activity.

In vitro susceptibility tests to determine MICs were performed by the broth microdilution method according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards proposed guidelines (49), with some modifications. Stock solutions of colistin methanesulfonate (Sigma) and polymyxin B (Sigma) were prepared in sterile water to obtain concentrations of 20 and 0.5 mg/ml, respectively. Stock solutions of cecropin A and B were prepared in 0.5% acetic acid to obtain a concentration of 0.4 mg/ml. The antibiotics were then added directly to 96-well microtiter plates in twofold serial dilutions. A total of 104 CFU of bacteria that had been grown overnight was dispensed into each microdilution well. The MICs were determined in Mueller-Hinton broth (Biokar) following incubation at 30°C for 48 h. The microtiter plates were read by visual observation.

RNA manipulations.

Total RNA was prepared from 10-ml cultures of P. luminescens as previously described (16). Primer extension was performed by using standard procedures (59) with some modifications, as previously described (16). Briefly, 10 ng of an end-labeled primer was annealed with total RNA, and a reverse transcriptase reaction was performed with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Roche) at 42°C for 90 min. As a reference, sequencing reactions were performed with a Thermosequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit (Amersham) with the same primer used to map the 5′ termini of phoP mRNA, phoP4. The oligonucleotide used in primer extension experiments was end labeled with phage T4 polynucleotide kinase (BioLabs) and [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) by using standard procedures (59).

LPS preparation.

P. luminescens strains TT01 and PL2104 were grown to the log phase on ED*-glucose synthetic medium supplemented with MgCl2 at either a micromolar or millimolar concentration. LPS was obtained by hot phenol-water extraction. Next, LPS extracts were mixed with 1 volume of loading buffer (Sigma) containing 7% β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min. LPS profiles were analyzed by Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) by using a 16.5% acrylamide gel. The gel was fixed overnight in 25% isopropanol-4% acetic acid and then silver stained by using the method of Tsai and Frasch (67).

Sequence comparisons.

Amino acid sequence similarity searches were carried out by using the BLASTP software (2, 3).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

phoPQ and pbgP123E1234 sequence data have been deposited in the EMBL databases under accession number BX470251.

RESULTS

Identification of the PhoP-PhoQ two-component system in P. luminescens.

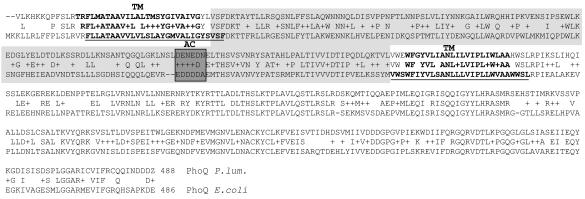

The genome sequence of P. luminescens TT01 was recently completely deciphered (18). Nineteen two-component regulatory systems were found in the genome, including a counterpart of a known PhoP-PhoQ system found in gram-negative bacteria. The organization of the P. luminescens phoPQ locus is similar to that of the loci in Salmonella sp. and E. coli; both genes are located downstream of purB, encoding adenylsuccinate lyase. The sizes of the predicted P. luminescens regulator (222 residues) and sensor (487 residues) are similar to the sizes of the Salmonella and E. coli regulator (224 and 222 residues, respectively) and sensor (487 residues), and the sequences exhibit 70 and 48% identity at the amino acid level. In addition, the domain organization is similar. PhoP is a typical response regulator, containing an N-terminal receiver domain and a C-terminal helix-turn-helix motif. The putative site of phosphorylation (D58) is conserved. PhoQ contains an N-terminal periplasmic sensor domain, delineated by two hydrophobic transmembrane sequences predicted in silico (13), coupled to a cytoplasmic transmitter domain whose sequence is particularly well conserved. There are differences in the extracellular sensor domain (Fig. 1). One interesting example of the divergence is in the ligand binding site for the divalent cations Mg2+ and Ca2+, called the acidic cluster (69). Although the amino acid sequences were strikingly different in this cluster (DENEDNE in P. luminescens and EDDDDAE in E. coli), conservative conversions maintain several acidic amino acids clustered in the same region, suggesting that this region also serves as a ligand binding site in the P. luminescens PhoQ sensor (69).

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of P. luminescens and E. coli sensor PhoQ showing the ligand binding site, designated the acidic cluster (AC), which is enclosed in a shaded box. Periplasmic domains are delineated by two hydrophobic transmembrane sequences (TM) indicated by boldface type. P. lum., P. luminescens.

Characterization and expression of the phoPQ operon from P. luminescens.

phoQ starts 19 bases downstream from the coding sequence of phoP, suggesting that the two genes form a single transcription unit. Primer extension analysis with total P. luminescens RNA (up to 50 μg of RNA) revealed very faint traces of phoP mRNA in exponentially growing P. luminescens cells (data not shown). To map precisely the transcription start point, we overexpressed the transcriptional regulatory region using plasmid pDIA607. Total RNA was extracted during the exponential growth phase at 30°C, and primer extension analysis was performed with 25 μg of RNA and primer phoP4 (Fig. 2B). A single start point was mapped at an adenosine residue located 99 bp upstream from the translation start codon of phoP (Fig. 2A). This start point was preceded by −35 and −10 sequences (TTGCTG-17 bp-TAACAT) with significant similarity to the consensus boxes for sigma 70 promoters in enterobacteria.

FIG. 2.

(A) Nucleotide sequences of the 5′ region of phoP from P. luminescens, E. coli, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mg2+-responsive promoter sequences (−35 and −10 boxes) are enclosed in boxes, and transcriptional start sites are indicated by arrows (Pi, position 1 of Mg2+-inducible promoter; Pc, position 1 of constitutive promoter). The Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) is underlined. The first codon of the coding sequence of phoP is indicated by boldface type. The newly identified PhoP box, which consists of a direct repeat of the heptanucleotide sequence (T)G(T)TT(AA), is underlined by arrows. P. lum., P. luminescens; S. typh., S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. (B) Primer extension analysis of phoP transcripts in a P. luminescens strain overexpressing phoPQ (pDIA607). Total RNA was extracted from an exponential culture grown at 30°C. The arrowhead indicates the position of the extension product obtained. (C) Analysis of P. luminescens phoP mRNA abundance following exposure to various magnesium and calcium concentrations during exponential growth at 30°C in ED* synthetic medium. Left lane, ED* medium supplemented with 20 μM MgCl2; middle lane, ED* medium supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2; right lane, ED* medium supplemented with 20 μM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2. Equal amounts of each RNA (25 μg) were used. Experiments were done in triplicate, and the data shown are the data from one representative experiment. For the graph the relative phoP mRNA abundance obtained with the lowest level of mRNA was defined as 1.

To examine the sensing function of PhoPQ in P. luminescens, the effect of the Mg2+ and Ca2+ divalent cations on phoP expression was investigated by primer extension. Total RNAs from P. luminescens cells transformed with plasmid pDIA607 were prepared following exposure to various Mg2+ and Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 2C). Expression of phoP was inversely proportional to the Mg2+ concentration; the maximal activation was observed in medium containing a micromolar concentration of MgCl2. Addition of a millimolar concentration of Mg2+ decreased the phoP mRNA abundance about fivefold. Growth in the presence of Ca2+ slightly repressed (less than twofold) phoP expression compared with expression in low-Mg2+medium. Thus, phoP expression in P. luminescens is controlled by a unique Mg2+- and Ca2+-inducible promoter. It is interesting that in Salmonella and E. coli, the phoPQ operon is transcribed from two promoters (Fig. 2A), one which is active during growth in the presence of a low concentration of Mg2+ and is dependent on PhoPQ and one which is constitutive (26, 39).

Construction and phenotypic characterization of a phoP mutant.

To obtain clues concerning the functional role of PhoPQ in P. luminescens, the regulator PhoP was inactivated by allelic exchange. A mutant strain (PL2104) was constructed with plasmid pDIA604 harboring a chloramphenicol cassette in place of the phoP internal coding region (see Materials and Methods).

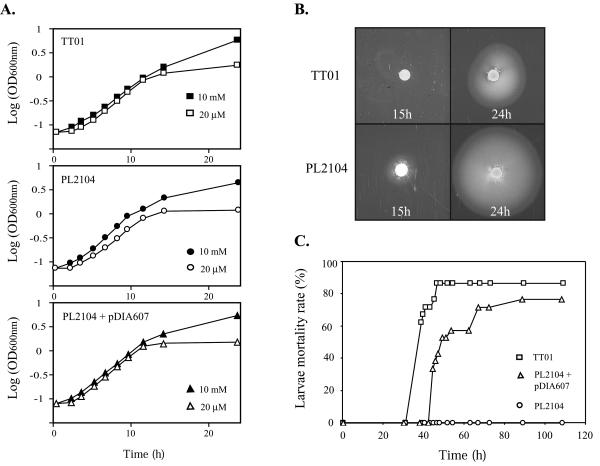

The mutant was compared to the wild-type strain in an analysis of several phenotypic traits specific to P. luminescens. Both strains adsorbed dye from nutrient bromothymol blue agar and produced antibiotics and paracrystalline inclusion bodies at levels indistinguishable from those produced by the wild-type strain. The phoP mutation did not have any effect on exponential- or stationary-phase cell morphology in Schneider medium (data not shown). We next examined the growth characteristics of strains TT01, PL2104, and PL2104 complemented with copies of phoPQ supplied on the low-copy-number mobilizable plasmid pDIA607 in synthetic medium containing either 10 mM or 20 μM MgCl2. Except for a longer lag phase for strain PL2104, no significant differences were detected among the strains in the exponential or stationary growth phase (Fig. 3A). The growth rate appeared to be only slightly lower when the magnesium level was low for PL2104. At very low concentrations of magnesium (less than 0.1 μM), all strains grew slowly and reached the stationary phase at a low cell density (optical density, 0.6 to 0.7). At intermediate magnesium concentrations (10 to 20 μM), all strains had similar specific growth rates and reached the stationary phase at an optical density of 1.2 to 1.5. At both concentrations, loss of pigmentation was observed in 24-h-old cultures in all cases. At a relatively high concentration of magnesium (10 mM), all strains grew to an optical density of 5 to 5.5, and the culture broths were pigmented. These findings differ from what was observed with Salmonella or Neisseria; phoP mutants of these organisms did not grow at reduced (micromolar) magnesium levels (38, 65).

FIG. 3.

Phenotypic analysis of the phoP mutation in P. luminescens. (A) Growth curves for P. luminescens wild-type strain TT01, phoP knockout mutant PL2104, and complemented phoP mutant PL2104(pDIA607) grown in ED* synthetic medium containing 10 mM MgCl2 (solid symbols) or 20 μM MgCl2 (open symbols). OD600nm, optical density at 600 nm. (B) Motility of the P. luminescens TT01 and PL2104 strains on semisolid (0.3% [wt/vol] agar) medium plates. Plates were incubated for 15 to 24 h at 30°C. (C) Mortality of S. littoralis infected with the P. luminescens wild-type strain, phoP knockout mutant, and complemented phoP mutant. Bacteria obtained at the end of the exponential phase were injected into fourth-instar larvae. The mortality values are based on data obtained after injection into 20 larvae. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

The first trait markedly affected by the mutation was swarming in semisolid agar (Fig. 3B). In 0.3% (wt/vol) agar the phoP mutant reproducibly migrated farther from the point of inoculation than the parent migrated. This was due to early onset of the spreading behavior; the mutant started to spread 15 h after inoculation, while the wild-type strain started to spread only after 20 h (Fig. 3B). Wild-type motility was restored when PL2104 was complemented with pDIA607 (data not shown).

Effect of the phoP mutation on virulence in insects.

To examine the effect of the phoP mutation on virulence in insects, we injected similar doses (500 to 1,000 CFU) of parental (TT01), phoP (PL2104), and phoP-complemented [PL2104 (pDIA607)] cells directly into the hemocoel of S. littoralis larvae and monitored insect mortality after injection (Fig. 3C). Remarkably, no mortality was observed with PL2104. Furthermore, septicemia was observed 24 h after injection of wild-type bacteria, while no bacteria were observed in the hemolymph of larvae that received the phoP mutant. This is remarkable because living cells of wild-type P. luminescens are highly virulent when they are injected into the hemolymph of insects. As previously reported (9), TT01 killed 90% of the larvae in less than 48 h. Substantiating the role of phoPQ, complementation with pDIA607 restored virulence, although with a slight delay. This delay has two possible explanations. Some of the transformed cells may have lost the plasmid during the in vivo infection and therefore may have behaved like phoP mutants. Without antibiotic selection pressure, in vitro 70% of the bacterial population lost pDIA607 after 48 h of culture. Alternatively, tight regulation of phoPQ expression may be necessary for full virulence.

According to the definition proposed by Bucher (11), insect-pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that produce a lethal septicemia from inocula, usually less than 10,000 cells per insect. Injection of high doses (about 105 CFU) revealed that the phoP mutant is avirulent (data not shown). Identification of the genes regulated by PhoPQ is therefore crucial for identifying major virulence determinants for entomopathogenicity.

PhoP-PhoQ governed LPS modification in Mg2+-limited medium.

The bacterial envelope is the first barrier against environmental aggression. Since LPS is the major surface molecule and pathogenic factor of gram-negative bacteria, a role for LPS in P. luminescens virulence has been proposed (20). Several gram-negative bacteria have the ability to modify, in a PhoP-dependent manner, their LPS in response to environmental conditions, especially in Mg2+-depleted media. The PhoPQ regulon plays a key role in the regulation of LPS production in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (21, 35) and in the regulation of lipooligosaccharide production in Yersinia pestis (37).

Before investigating whether the LPS of P. luminescens was affected by a phoP deletion, we examined the P. luminescens LPS biosynthetic pathway in silico. To do this, BLASTP searches were performed with the translation products of the coding sequences present in the genome to identify putative LPS biosynthetic genes. This analysis revealed that P. luminescens possesses four large loci similar to the lpx/dnaE (lipid A), waa (LPS core), wbl (O antigen), and wec (enterobacterial common antigen) clusters found in other Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 4) (54). Both the organization and the putative functions of genes found in the TT01 clusters homologous to lpx/dnaE and wec were identical to those of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. The organization and genes in the waa region were more divergent, indicating that the number and nature of the carbohydrate subunits that compose the core oligosaccharide of the LPS are different in P. luminescens. The putative strain-specific O-antigen wbl locus of P. luminescens has few genes homologous to those of the E. coli wbb operon. It is composed of 29 genes interrupted by a putative transposase. Of the 29 wbl genes, 9 encode proteins that are similar to sugar or UDP-sugar dehydrogenases (WblAB), epimerase (WblH), dehydratase (WblV), kinase (WblW), isomerase (WblX), phosphatase (WblZ), hydrolyase (WblK), and a homologue of the protein encoded by the trsG gene (WblM) involved in O- antigen biosynthesis in other organisms. Three other genes encode proteins that are similar to amino or hexapeptide transferases (WblCDQ). The gene cluster is also predicted to code for two sugar 1-phosphate nucleotidyltransferases (WblOY) and six glycosyltransferases used for transfer of sugars to build the O unit (WblGIJFTU). Several genes were also found to be similar to genes which carry out specific assembly or processing steps during conversion of the O unit to the O antigen as part of the complete LPS, such as two putative O antigen translocase genes (wzxAB), one potential O-antigen polymerase gene (wzy), and one gene coding for a protein weakly similar to polymer ligase (wblL), but not to the chain length determinant gene (wzz). Finally, the cluster contains four genes with unknown functions, including three genes encoding putative transmembrane proteins (wblENR). Therefore, P. luminescens likely produces an LPS consisting of three distinct structural regions: lipid A, the core oligosaccharide, and the O-antigen polymer (strain specific or enterobacterial common antigen).

FIG. 4.

Organization of genes in lpx (A), waa (B), wbl (C), and wec (D) gene clusters in P. luminescens TT01 and comparison with the genes of E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. Genes without homologues in the E. coli genome are indicated by shading. The arrows indicate the direction of transcription of the genes (approximately drawn to scale). The lpx, waa, and wec regions are involved in initial steps of lipid A synthesis, core assembly, and enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) synthesis, respectively. S. thyp., S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; P. lum., P. luminescens.

The LPS was extracted from strains TT01, PL2104, and complemented PL2104 grown in low-Mg2+ or high-Mg2+ medium and was subjected to Tricine-SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 5). A comparison of the extracted LPS produced in the presence of a millimolar concentration of MgCl2 (Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 3) did not reveal any difference among the strains, either in the O-antigenic region (upper portion of the gel) or in the core-lipid A region (lower part of the gel). In an Mg2+-limited environment (lanes 4 to 6), the LPS structure in the core-lipid A region was modified, as shown by the greater intensity of the top band than of the two lower bands. This modification was not observed in the mutant LPS (lane 5), suggesting that it was PhoP dependent. Indeed, in the phoPQ-complemented mutant, this band was clearly overproduced (lane 6). As the PhoPQ regulon was induced during growth of P. luminescens in low-Mg2+ medium, the inability to express the PhoPQ regulon must have been responsible for the change observed in the lipid A-core structure.

FIG. 5.

LPS Tricine-SDS-PAGE profiles of the parental P. luminescens strain (TT01), the phoP mutant (PL2104), and the complemented phoP mutant [PL2104(pDIA607)]. The positions of O-antigen and lipid A-core regions are indicated. Lane 1, TT01 control in high-Mg2+ medium; lane 4, TT01 control in low-Mg2+ medium; lane 2, PL2104 in high-Mg2+ medium; lane 5, PL2104 in low-Mg2+ medium; lane 3, PL2104(pDIA607) (PhoPQ+) in high-Mg2+ medium; lane 6, PL2104(pDIA607) (PhoPQ+) in low-Mg2+ medium.

Identification of a PhoP-dependent Mg2+-responsive locus involved in lipid A modification.

In order to identify the possible nature of PhoP- and Mg2+-dependent LPS alteration in P. luminescens, a BLASTP comparison of the genomic DNA sequence of P. luminescens with the few known Salmonella PhoP-activated genes involved in LPS modification was performed. lpxO and pagL were found to be unique to Salmonella, but homologues of pagP and the pbgPE operon (also designated pmrHFIJKLM) were identified in P. luminescens. pagP encodes an outer membrane protein responsible for incorporation of palmitate into the lipid A moiety of the LPS (55). The seven-gene pbgPE operon mediates the synthesis of 4-aminoarabinose and incorporation of this molecule into the 4′-terminal phosphate of lipid A (33, 34) in association with pmrE (formerly pagA or ugd) (33, 47), a gene predicted to encode a UDP-glucose dehydrogenase that has several homologues in P. luminescens. The P. luminescens pbgPE locus is predicted to contain seven genes transcribed unidirectionally, with no more than 33 bp separating any two open reading frames. These genes encode seven proteins whose sequences and sizes are similar to those of the Salmonella or E. coli homologues. In both S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli, the pbgPE operon is preceded by the divergently transcribed homologous gene pmrG (previously designated pagH and ais, respectively) and is immediately followed by the divergently transcribed pmrD gene; both genes are thought to be PhoP regulated (58, 71). In P. luminescens, the pbgPE operon is flanked by two genes that are somewhat similar to the vitamin B12 transport system genes (btuCD) and by a gene similar to the gene encoding the putative lipoprotein NlpC precursor.

The transcription start site of pbgP1 and pagP was determined by primer extension, and the abundance of the corresponding mRNA was determined in strains TT01, PL2104, and PL2104(pDIA607). P. luminescens total RNA was extracted from cells grown to the mid-log phase in ED*-glucose medium supplemented with a low concentration (20 μM) or a high concentration (10 mM) of MgCl2. We found that expression of both pagP (Fig. 6 and data not shown) and pbgP1 (Fig. 6) were dependent on the extracellular Mg2+ concentration. The expression of these genes was induced by a micromolar concentration of Mg2+ but was repressed by a millimolar concentration. pbgP1 expression was suppressed in the phoP mutant strain PL2104 under both conditions. phoPQ copies supplied by pDIA607 restored normal Mg2+-regulated expression of pbgP1 in PL2104, and higher levels of expression were observed in the complemented strain. Curiously, pagP expression was not significantly affected by the phoP deletion. This indicated that PhoPQ positively controls pbgPE expression in an Mg2+-dependent manner, while pagP expression is induced in Mg2+-depleted medium in a PhoPQ-independent manner.

FIG. 6.

Primer extension analysis of pbgP1 and pagP mRNA abundance in strain TT01, strain PL2104, and strain PL2104 complemented with pDIA607 at various magnesium concentrations during P. luminescens exponential growth at 30°C in ED*-glucose synthetic medium supplemented with 20 μM MgCl2 (−) or 10 mM MgCl2 (+). Equal amounts of each RNA sample (50 μg) were used. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Sensitivity to APs.

phoP mutants of several intracellular pathogens are highly susceptible to a variety of APs (30). The PhoPQ-controlled ability to modify the lipid A moiety of LPS is one of the main determinants that mediate resistance to these molecules. Indeed, addition of aminoarabinose or palmitate to lipid A in a low-Mg2+-concentration environment results in a reduction in the overall LPS negative charge, leading to decreased binding of APs to the bacterial surface (6, 33, 22). This prompted us to examine the sensitivity of both TT01 and PL2104 to these compounds.

P. luminescens antipeptide resistance was determined by the broth microdilution method in Mueller-Hinton medium (which contained 750 μM MgCl2 according to the manufacturer [Biokar]). Different APs were tested (Table 1). The phoP mutant was more sensitive to colistin, cecropins A and B, and polymyxin B than the wild type and the phoP-complemented mutant were. Cecropins are considered to be the most active antimicrobial components. These small cationic peptides are naturally produced in many insects, including S. littoralis larvae (12).

TABLE 1.

MICs of four APs for the P. luminescens wild type, phoP mutant, and complemented mutant grown in Mueller-Hinton broth

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | Cecropin A | Cecropin B | Polymyxin B | |

| Wild type (TT01) | >10,000 | >25a | >25a | >250 |

| phoP mutant (PL2104) | 20 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 1-3 |

| Complemented phoP mutant [PL2104 (pDIA607)] | >10,000 | 12.5 | >25a | >250 |

Higher concentrations were not tested due to the susceptibility of P. luminescens to the acetic acid used as a solvent.

DISCUSSION

A homologue of the two-component signal transduction system PhoPQ has been identified in P. luminescens. A knockout mutant (PL2104) has many of the characteristics of other phoP mutants of mammalian pathogens.

(i) PL2104 is more motile than its parent, strain TT01. A similar PhoPQ-dependent effect on motility has been observed in Salmonella and P. aeruginosa. In Salmonella, decreased flagellin expression and cell motility are coregulated by low pH and are dependent on activation of the phoPQ pathway, which directly or indirectly negatively regulates transcription of the flagellin gene fliC (1). Similarly, in P. aeruginosa, a phoQ mutant had a decreased ability to swim on soft agar, while a phoP null strain was considered a superswimmer (10). Preliminary data indicate that fliC is also up-regulated in PL2104 (unpublished data).

(ii) We demonstrated that the LPS, which comprises 40% of the outer membrane layer, is altered in a PhoP-dependent manner when there is a change in the magnesium concentration. Identification in P. luminescens of the pbgPE locus, an operon involved in synthesis of aminoarabinose and incorporation of this molecule into the lipid A moiety, and characterization of this locus as an Mg2+- and PhoP-dependent operon, substantiated the likely role played by PhoPQ in this process.

(iii) PL2104 showed enhanced sensitivity to several APs (i.e., cecropins A and B, colistin, and polymyxin). This may have been partly correlated with its inability to perform PhoPQ-controlled LPS modification in low-Mg2+-concentration conditions. One mechanism of AP resistance consists of reduced electrostatic interactions between an AP and the negatively charged bacterial surface, which may occur in P. luminescens through modifications of lipid A phosphate with aminoarabinose or changes in the overall charge of the peculiar O antigen that it harbors. Another mechanism may involve the presence of long O-specific side chains that sterically hinder the ability of AP to bind to the deeper parts of LPS and prevent disruption of the bacterial outer membrane.

(iv) Finally, deletion of phoP resulted in a complete loss of virulence when insects were infected with P. luminescens, while complementation restored virulence. PhoPQ-dependent defects, such as envelope alterations, greater susceptibility to insect antibacterial peptides, increased motility promoting the early recognition of flagellar components by an immune response, or the inability to impair immune response activation through LPS signaling, may contribute to the observed avirulence of the mutant.

Surprisingly, although the primary function of PhoPQ in other gram-negative bacteria is to control physiological adaptations in response to an Mg2+-limiting environment (30, 65), the P. luminescens mutant is able to grow in medium containing a low level (micromolar) of magnesium without apparent difficulty. This observation might reflect a difference in control of Mg2+ uptake in P. luminescens. In S. enterica, three transporters mediate Mg2+ uptake; these are the P-type ATPases MgtA and MgtB, whose expression is transcriptionally induced in the presence of a low Mg2+ concentration by PhoPQ, and the constitutive major Mg2+ transporter CorA (62). Salmonella mutants defective in mgtA, mgtB, phoQ, or phoP are defective for growth in the presence of a low Mg2+ concentration (65), even though CorA is expressed and functional (63). BLASTP searches revealed little homology between Salmonella MgtA and MgtB and various putative P-type ATPases in P. luminescens, including a probable copper-transporting ATPase (AtcU), a zinc-transporting ATPase (ZntA), and a potassium-transporting ATPase (KdpB). In contrast, CorA, the most phylogenetically widespread Mg2+ transporter, is conserved. Further work is needed to determine the process of Mg2+ import in P. luminescens, but our analysis suggests that PhoPQ might not play a crucial role in this transport. Consistent with this hypothesis, the PhoPQ-independent pagP induction in the presence of a low Mg2+ concentration indicates that there must be additional systems that regulate gene expression in response to an Mg2+-limiting environment.

As in Salmonella, phoP gene expression responds to the extracellular Mg2+ concentration, indicating that this cation may be one of the physiological signals that affect the phoPQ-dependent response in P. luminescens. phoP expression also responds to a low Ca2+ concentration but not to the same extent (Fig. 2C). The promoter region of phoP differs from that of E. coli and Salmonella. In both species, the autogenously controlled phoPQ operon is transcribed from two promoters, a PhoPQ-dependent promoter that is active only during growth in the presence of a low Mg2+ concentration and another promoter that is constitutive (26, 39, 64). The relative positions of the constitutive and regulated promoters differ in the two organisms, but an authentic PhoP binding site consisting of a direct repeat of the heptanucleotide sequence (T)G(T)TT(AA) is conserved 25 bp upstream of the Mg2+-inducible transcription start site of phoPQ (39, 72). In P. luminescens, one Mg2+-inducible transcript was found under the culture conditions used. This transcript has a long 5′ untranslated region, and no obvious PhoP box is apparent upstream of its transcription start point. The very faint level of phoP mRNA detected suggested that P. luminescens cells may be sensitive to very small changes in the amount of PhoP. It is also possible that factors present in the insect larvae control expression of the operon. Several overlapping promoter-like sequences can be identified upstream of the transcriptional start that could play a role in particular environments. Interestingly, the regulation of the Mg2+-dependent expression of pagP and pbgPE, coding for enzymes involved in LPS modifications, also slightly differs from the regulation of the homologs in Salmonella. In Salmonella, both loci are activated by PhoP. The control is direct for pagP but indirect for pbgPE and occurs via PmrAB, a two-component system that itself is induced by PhoPQ (30). In P. luminescens, PmrAB is not conserved, and although expression of both loci is Mg2+ dependent, expression of only pbgPE seems to be PhoPQ dependent. We do not know at present the regulatory mechanisms operating in this organism for pagP and pbgPE. Nevertheless, our results strongly support the hypothesis that the PhoPQ signal transduction system is able to respond to the Mg2+ content of the host environment and transduce the signal to either induce or repress expression of genes needed to establish an infection in insects. However, whether the Mg2+ concentration is directly sensed by PhoPQ or by a PhoPQ-independent mechanism which in turn regulates phoPQ is still an open question.

The essential role played in vivo by PhoPQ in P. luminescens pathogenicity is somewhat unexpected for the following reasons. This system is known to control virulence, especially in intracellular pathogens, while experiments suggest that P. luminescens is extracellular in insects (60). In Salmonella and other mammalian pathogens, the external magnesium level sensed by PhoQ is thought to be the signal that indicates to the organism whether it is residing in an intracellular or extracellular compartment in the host (29). Mammalian extracellular fluids contain high Mg2+ and Ca2+ levels (millimolar). Pathogens encounter low intracellular levels (micromolar) of both cations inside macrophages or epithelial cells. Phytophagous insects, such as Spodoptera, have high Mg2+ and Ca2+ levels in the hemocoel (i.e., 33 mM Mg2+ and 3 mM Ca2+ in Spodoptera exigua) (48). Although these concentrations should theoretically repress P. luminescens phoPQ expression, inactivation of phoP prevents bacterial proliferation in the hemolymph in vivo and eliminates virulence. This prompted us to make several predictions to account for these apparent discrepancies, noting that compartmentalization is ubiquitous in biological processes. (i) Efficient Photorhabdus infection might start with a microenvironment in which the Mg2+ concentration is particularly low. Within minutes of its appearance in the hemolymph, the bacterium is recognized by the insect hemocytes and encapsulated in nodules, from which it rapidly reemerges (17). The actual mineral ion concentrations surrounding the bacterium inside the nodules are difficult to ascertain but might be quite different from those in the hemolymph. (ii) It is also possible that Photorhabdus has an intracellular phase at some point during the infection. This occurs with Y. pestis, a pathogen that is normally present extracellularly. In this organism, PhoP is necessary early in infection during an intracellular phase within phagocytic cells (50). (iii) It is possible that PhoPQ is sensitive to other signals present in vivo in the hemocoel. It has been suggested previously that in Erwinia chrysanthemi and Providencia stuartii (42, 56) the PhoPQ system may sense chemical signals other than divalent cations. In E. coli, the system has been shown to respond to a mildly acidic pH and acetate in addition to Mg2+ (4, 41).

In conclusion, the work described in this report showed the central role played by the phoPQ regulon in Photorhabdus virulence in insects. Further studies are required to understand how and why the PhoP mutant of P. luminescens is completely impaired in terms of virulence. Identification of the essential role played in virulence by the PhoPQ signal transduction system is an important step towards understanding how entomopathogenic bacteria such as P. luminescens perform the switch from symbiosis to pathogenicity. This finding highlights the fact that the PhoPQ regulatory system promotes pathogen resistance to host innate immunity in vertebrates (22) and plants (24, 42) and also in insects.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Boutonnier for helpful technical assistance with LPS preparation.

Financial support was provided by the Institut Pasteur, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA 2171), and the French ASG program involving Bayer CropScience, the Institut Pasteur, and INRA, supported by the Ministry of Industry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, P., R. Fowler, N. Kinsella, G. Howell, M. Farris, P. Coote, and C. D. O'Connor. 2001. Proteomic detection of PhoPQ- and acid-mediated repression of Salmonella motility. Proteomics 1:597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Protein database searches for multiple alignments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87:5509-5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearson, B. L., L. Wilson, and J. W. Foster. 1998. A low pH-inducible, PhoPQ-dependent acid tolerance response protects Salmonella typhimurium against inorganic acid stress. J. Bacteriol. 180:2409-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertin, P., N. Benhabiles, E. Krin, C. Laurent-Winter, C. Tendeng, E. Turlin, A. Thomas, A. Danchin, and R. Brasseur. 1999. The structural and functional organization of H-NS-like proteins is evolutionarily conserved in Gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 31:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop, R. E., H. S. Gibbons, T. Guina, M. S. Trent, S. I. Miller, and C. R. Raetz. 2000. Transfer of palmitate from phospholipids to lipid A in outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 19:5071-5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn, M., E. Golubeva, D. Bowen, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 1998. A novel insecticidal toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens, toxin complex a (Tca), and its histopathological effects on the midgut of Manduca sexta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3036-3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen, D., M. Blackburn, T. Rocheleau, C. Grutzmacher, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 2000. Secreted proteases from Photorhabdus luminescens: separation of the extracellular proteases from the insecticidal Tc toxin complexes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brillard, J., E. Duchaud, N. Boemare, F. Kunst, and A. Givaudan. 2002. The PhlA hemolysin from the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens belongs to the two-partner secretion family of hemolysins. J. Bacteriol. 184:3871-3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinkman, F. S., E. L. Macfarlane, P. Warrener, and R. E. Hancock. 2001. Evolutionary relationships among virulence-associated histidine kinases. Infect. Immun. 69:5207-5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucher, G. E. 1960. Potential bacterial pathogens of insects and their characteristics. J. Invert. Pathol. 2:172-195. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi, C. S., I. H. Lee, E. Kim, S. I. Kim, and H. R. Kim. 2000. Antibacterial properties and partial cDNA sequences of cecropin-like antibacterial peptides from the common cutworm, Spodoptera litura. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 125:287-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claros, M. G., and G. von Heijne. 1994. TopPred II: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput. Applic. Biosci. 10:685-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daborn, P. J., N. Waterfield, M. A. Blight, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 2001. Measuring virulence factor expression by the pathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens in culture and during insect infection. J. Bacteriol. 183:5834-5839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daborn, P. J., N. Waterfield, C. P. Silva, C. P. Au, S. Sharma, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 2002. A single Photorhabdus gene, makes caterpillars floppy (mcf), allows Escherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99:10742-10747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derzelle, S., E. Duchaud, F. Kunst, A. Danchin, and P. Bertin. 2002. Identification, characterization, and regulation of a cluster of genes involved in carbapenem biosynthesis in Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3780-3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowds, B. C. A., and A. Peters. 2002. Virulence mechanisms, p. 79-98. In R. Gaugler (ed.), Entomopathogenic nematology. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 18.Duchaud, E., C. Rusniok, L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, A. Givaudan, S. Taourit, S. Bocs, C. Boursaux-Eude, M. Chandler, J.-F. Charles, E. Dassa, R. Derose, S. Derzelle, G. Freyssinet, S. Gaudriault, C. Médigue, A. Lanois, K. Powell, P. Siguier, R. Vincent, V. Wingate, M. Zouine, P. Glaser, N. Boemare, A. Danchin, and F. Kunst. 2003. The Photorhabdus luminescens genome reveals a biotechnological weapon to fight microbes and insect pests. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1307-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunphy, G. B. 1994. Interaction of mutants of Xenorhabdus nematophilus (Enterobacteriaceae) with antibacterial systems of Galleria mellonella larvae (Insecta: Pyralidae). Can. J. Microbiol. 40:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunphy, G. B., and J. M. Webster. 1988. Virulence mechanisms of Heterorhabditids heliothidis and its bacterial associate, Xenorhabdus luminescens, in non-immune larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonela. Int. J. Parasitol. 18:729-737. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst, R. K., E. C. Yi, L. Guo, K. B. Lim, J. L. Burns, M. Hackett, and S. Miller. 1999. Specific lipopolysaccharide found in cystic fibrosis airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 286:1561-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernst, R. K., T. Guina, and S. I. Miller. 2001. Salmonella typhimurium outer membrane remodeling: role in resistance to host innate immunity. Microbes Infect. 3:1327-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer-Le Saux, M., V. Viallard, B. Brunel, P. Normand, and N. E. Boemare. 1999. Polyphasic classification of the genus Photorhabdus and proposal of new taxa: P. luminescens subsp. luminescens subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. laumondii subsp. nov., P. temperata sp. nov., P. temperata subsp. temperata subsp. nov., and P. asymbiotica sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1645-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flego, D., R. Marits, A. R. Eriksson, V. Koiv, M. B. Karlsson, R. Heikinheimo, and E. T. Palva. 2000. A two-component regulatory system, pehR-pehS, controls endopolygalacturonase production and virulence in the plant pathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:447-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forst, S., and D. Clarke. 2002. Bacteria-nematode symbiosis, p. 57-77. In R. Gaugler (ed.), Entomopathogenic nematology. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 26.Garcia Vescovi, E., F. C. Soncini, and E. A. Groisman. 1996. Mg2+ as an extracellular signal: environmental regulation of Salmonella virulence. Cell 84:165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia Vescovi, E. G., Y. M. Ayala, E. Di Cera, and E. A. Groisman. 1997. Characterization of the bacterial sensor protein PhoQ: evidence for distinct binding sites for Mg2+ and Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 272:1440-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Givaudan, A., and A. Lanois. 2000. flhDC, the flagellar master operon of Xenorhabdus nematophilus: requirement for motility, lipolysis, extracellular hemolysis, and full virulence in insects. J. Bacteriol. 182:107-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groisman, E. A. 1998. The ins and outs of virulence gene expression: Mg2+ as a regulatory signal. Bioessays 20:96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groisman, E. A. 2001. The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ. J. Bacteriol. 183:1835-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groisman, E. A., C. Parra-Lopez, M. Salcedo, C. J. Lipps, and F. Heffron. 1992. Resistance to host antimicrobial peptides is necessary for Salmonella virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89:11939-11943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guina, T., E. C. Yi, H. Wang, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 2000. A PhoP-regulated outer membrane protease of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium promotes resistance to alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. J. Bacteriol. 182:4077-4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunn, J. S. 2001. Bacterial modification of LPS and resistance to antimicrobial peptides. J. Endotoxin Res. 7:57-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunn, J. S., K. B. Lim, J. Krueger, K. Kim, L. Guo, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1998. Identification of PhoP-PhoQ activated genes within a duplicated region of the Salmonella typhimurium chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1171-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, J. S. Gunn, B. Bainbridge, R. P. Darveau, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hentschel, U., M. Steinert, and J. Hacker. 2000. Common molecular mechanisms of symbiosis and pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 8:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hitchen, P. G., J. L. Prior, P. C. Oyston, M. Panico, B. W. Wren, R. W. Titball, H. R. Morris, and A. Dell. 2002. Structural characterization of lipo-oligosaccharide (LOS) from Yersinia pestis: regulation of LOS structure by the PhoPQ system. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1637-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson, C. R., J. Newcombe, S. Thorne, H. A. Borde, L. J. Eales-Reynolds, A. R. Gorringe, A. R., S. G. Funnell, and J. J. McFadden. 2001. Generation and characterization of a PhoP homologue mutant of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1345-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato, A., H. Tanabe, H., and R. Utsumi. 1999. Molecular characterization of the PhoP-PhoQ two-component system in Escherichia coli K-12: identification of extracellular Mg2+-responsive promoters. J. Bacteriol. 181:5516-5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesley, J. A., and C. D. Waldbuerger. 2003. Repression of Escherichia coli PhoP-PhoQ signaling by acetate reveals a regulatory role for acetyl coenzyme A. J. Bacteriol. 185:2563-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llama-Palacios, A., E. Lopez-Solanilla, C. Poza-Carrion, F. Garcia-Olmedo, and P. Rodriguez-Palenzuela. 2003. The Erwinia chrysanthemi phoP-phoQ operon plays an important role in growth at low pH, virulence and bacterial survival in plant tissue. Mol. Microbiol. 49:347-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macfarlane, E. L., A. Kwasnicka, M. M. Ochs, and R. E. Hancock. 1999. PhoP-PhoQ homologues in Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulate expression of the outer-membrane protein OprH and polymyxin B resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 34:305-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller, S. I., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. Constitutive expression of the phoP regulon attenuates Salmonella virulence and survival within macrophages. J. Bacteriol. 172:2485-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller, S. I., A. M. Kukral, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1989. A two-component regulatory system (phoP phoQ) controls Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 86:5054-5058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moss, J. E., P. E. Fisher, B. Vick, E. A. Groisman, and A. Zychlinsky. 2000. The regulatory protein PhoP controls susceptibility to the host inflammatory response in Shigella flexneri. Cell. Microbiol. 2:443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mouslim, C., and E. A. Groisman. 2003. Control of the Salmonella ugd gene by three two-component regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 47:335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mullins, D. E. 1985. Chemistry and physiology of the hemolymph, p. 355-400. In G. A. Kerkut and L. I. Gilbert (ed.), Comprehensive insect physiology, biochemistry and pharmacology. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 49.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 50.Oyston, P. C., N. Dorrell, K. Williams, S. R. Li, M. Green, R. W. Titball, and B. W. Wren. 2000. The response regulator PhoP is important for survival under conditions of macrophage-induced stress and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 68:3419-3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pegues, D. A., M. J. Hantman, I. Behlau, and S. I. Miller. 1995. PhoP/PhoQ transcriptional repression of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes: evidence for a role in protein secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 17:169-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez, E., S. Samper, Y. Bordas, C. Guilhot, B. Gicquel, and C. Martin. 2001. An essential role for phoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 41:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quandt, J., and M. F. Hynes. 1993. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in gram-negative bacteria. Gene 127:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raetz, C. R. 1996. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: a remarkable family of bioactive macroamphiphiles, p. 1035-1063. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 55.Raetz, C. R. 2001. Regulated covalent modifications of lipid A. J. Endotoxin Res. 7:73-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rather, P. N., M. R. Paradise, M. M. Parojcic, and S. Patel. 1998. A regulatory cascade involving AarG, a putative sensor kinase, controls the expression of the 2′-N-acetyltransferase and an intrinsic multiple antibiotic resistance (Mar) response in Providencia stuartii. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1345-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson, W. H., T. M. Schmidt, and K. H. Nealson. 1988. Identification of an anthraquinone pigment and a hydroxystilbene antibiotic from Xenorhabdus luminescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1602-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roland, K. L., C. R. Esther, and J. K. Spitznagel. 1994. Isolation and characterization of a gene, pmrD, from Salmonella typhimurium that confers resistance to polymyxin when expressed in multiple copies. J. Bacteriol. 176:3589-3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 60.Silva, C. P., N. R. Waterfield, P. J. Daborn, P. Dean, T. Chilver, C. P. Au, S. Sharma, U. Potter, S. E. Reynolds, and R. H. Ffrench-Constant. 2002. Bacterial infection of a model insect: Photorhabdus luminescens and Manduca sexta. Cell. Microbiol. 4:329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon, R. 1984. High frequency mobilization of gram-negative bacterial replicons by the in vitro constructed Tn5-Mob transposon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 196:413-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith, R. L., M. T. Kaczmarek, L. M. Kucharski, and M. E. Maguire. 1998. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: regulation of mgtA and mgtCB during invasion of epithelial and macrophage cells. Microbiology 144:1835-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snavely, M. D., J. B. Florer, C. G. Miller, and M. E. Maguire. 1989. Magnesium transport in Salmonella typhimurium: Mg2+ transport by the CorA, MgtA, and MgtB systems. J. Bacteriol. 171:4761-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Soncini, F. C., E. Garcia Vescovi, and E. A. Groisman. 1995. Transcriptional autoregulation of the Salmonella typhimurium phoPQ operon. J. Bacteriol. 177:4364-4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soncini, F. C., E. Garcia Vescovi, F. Solomon, and E. A. Groisman. 1996. Molecular basis of the magnesium deprivation response in Salmonella typhimurium: identification of PhoP-regulated genes. J. Bacteriol. 178:5092-5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stock, A. M., V. L. Robinson, and P. N. Goudreau. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:183-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Sambeek, J., and A. Wiesner. 1999. Successful parasitation of locusts by entomopathogenic nematodes is correlated with inhibition of insect phagocytes. J. Invert. Pathol. 73:154-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waldburger, C. D., and R. T. Sauer. 1996. Signal detection by the PhoQ sensor-transmitter. Characterization of the sensor domain and a response-impaired mutant that identifies ligand-binding determinants J. Biol. Chem. 1271:26630-26636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waterfield, N., A. Dowling, S. Sharma, P. J. Daborn, U. Potter, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 2001. Oral toxicity of Photorhabdus luminescens W14 toxin complexes in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5017-5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wösten, M. M., and E. A. Groisman. 1999. Molecular characterization of the PmrA regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27185-27190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamamoto, K., H. Ogasawara, N. Fujita, R. Utsumi, and A. Ishihama. 2002. Novel mode of transcription regulation of divergently overlapping promoters by PhoP, the regulator of two-component system sensing external magnesium availability. Mol. Microbiol. 45:423-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]