Abstract

Most diagnosed early stage breast cancer cases are treated by lumpectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy, which significantly decreases the locoregional recurrence but causes inevitable toxicity to normal tissue. By using a technique of preparing liposomes carrying technetium-99m (99mTc), rhenium-186 (186Re), or rhenium-188 (188Re) radionuclides, as well as chemotherapeutic agents, or their combination, for cancer therapy with real time image-monitoring of pharmacokinetics and prediction of therapy effect, this study investigated the potential of a novel targeted focal radiotherapy with low systemic toxicity using radioactive immunoliposomes to treat both the surgical cavity and draining lymph nodes in a rat breast cancer xenograft positive surgical margin model. Immunoliposomes modified with either panitumumab (anti-EGFR), or bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) were remote loaded with 99mTc diagnostic radionuclide, and injected into the surgical cavity of female nude rats with positive margins post lumpectomy. Locoregional retention and systemic distribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes were investigated by nuclear imaging, stereofluorescent microscopic imaging and gamma counting. Histopathological examination of excised draining lymph nodes was performed. The locoregional retention of 99mTc-immunoliposomes in each animal was influenced by the physiological characteristics of surgical site of individual animals. Panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposome groups had higher intracavitary retention compared with the control liposome groups. Draining lymph node uptake was influenced by both the intracavitary radioactivity retention level and metastasis status. Panitumumab-liposome group had higher accumulation on the residual tumor surface and in the metastatic lymph nodes. Radioactive liposomes that were cleared from the cavity were metabolized quickly and accumulated at low levels in vital organs. Therapeutic radionuclide-carrying specifically targeted panitumumab- and bevacizumab- liposomes have increased potential compared to non-antibody targeted liposomes for post-lumpectomy focal therapy to eradicate remaining breast cancer cells inside the cavity and draining lymph nodes with low systemic toxicity.

Keywords: breast cancer, targeted therapy, immunoliposomes, intracavitary injection, metastasis

Introduction

Most breast cancer cases are diagnosed at early stage and treated by lumpectomy. Post-lumpectomy locoregional radiation therapy, such as brachytherapy, has been shown to decrease breast cancer recurrence and increase patient survival.1–5 However, current brachytherapy has limitations of 1) the relatively high radiation absorbed dose delivered to normal breast tissue, and 2) the inability to selectively treat involved lymph nodes and spare normal lymph nodes in the region. A focal adjuvant radionuclide therapy with low systemic toxicity which has sustained treatment to the surgical cavity and draining lymph nodes to decrease tumor recurrence may eliminate these limitations and spare excessive axillary lymph node dissection.

Liposomes have been used as drug carriers with increased therapeutic index for cancer therapy by improving drug delivery and controlled drug release.6,7 Studies have reported a sustained intratumoral or intracavitary retention 8–12 and a high draining lymph node concentration 13–18 of radioactive liposomes; focal delivery of radioactive liposomes has emerged as a low toxicity and efficient therapeutic strategy for early stage breast cancer.12,19

To enable specifically targeted cancer therapy, the liposome surface can be modified with functional molecules, including antibodies for active targeting of tumor cells. A promising target is epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a transmembrane glycoprotein with key roles in cancer growth. The activation of EGFR signaling pathway is associated with increased proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis. Inhibition of EGFR at extracellular ligand-binding sites with antibodies or intracellular tyrosine kinase domain with smaller molecular inhibitors is an important targeted treatment of tumors overexpressing EGFR.20–22 The fully humanized IgG2 monoclonal antibody, panitumumab (Vectibix®, Amgen, Inc.), which was initially approved to treat EGFR-expressing, metastatic colorectal cancer with disease progression by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA),has been reported to target EGFR in numerous cancer types including breast cancer.23 Another promising tumor target is cancer-related angiogenesis, which is required for tumor growth beyond a size of approximately 2–3 mm3.24 Many growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), are secreted by tumor cells to modulate the surrounding blood vessels during angiogenesis. VEGF, having four prototype members (VEGF-A, -B, -C and .D), is one of the primary growth factors associated with this function and has been verified as a promising molecular target to inhibit tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis in vivo.25–27 The humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech, Inc.) which neutralizes VEGF-A has been clinically used for cancer therapy.25,28–30

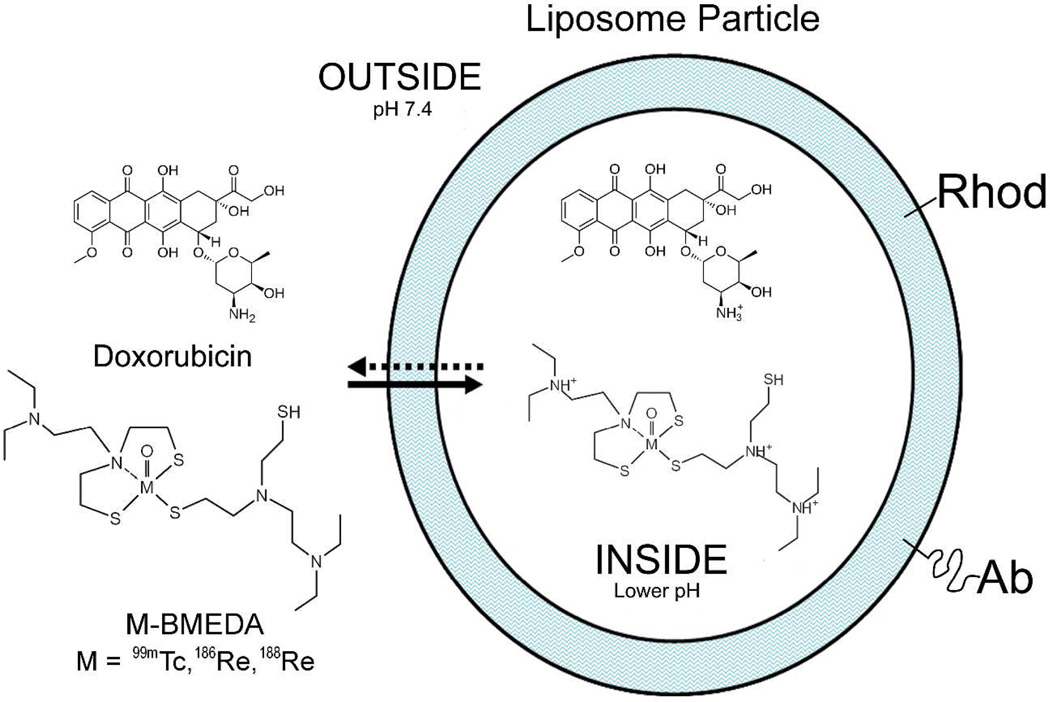

By using a technique of preparing liposomes carrying diagnostic technetium-99m (99mTc), and therapeutic rhenium-186 (186Re) / rhenium-188 (188Re) radionuclides, as well as chemotherapeutic agents, or their combination, for cancer therapy with the advantages of real time image monitoring of pharmacokinetics and prediction of therapy effect,18,31–33 we propose a new post-lumpectomy locoregional therapy using tumor targeted immunoliposomes modified with panitumumab or bevacizumab and containing the therapeutic beta-emitting radionuclide, rhenium-186/188 (186Re/188Re) (Figure 1). To determine whether the active targeting of radioactive immunoliposomes enhances the binding to positive tumor margin and draining lymph nodes in the treatment of breast cancer by post-lumpectomy intracavitary injection, we conjugated pegylated lipid with panitumumab or bevacizumab and incorporated the antibody-modified pegylated lipids into plain liposomes containing trace amounts of fluorescent rhodamine-lipid using post-insertion method.34–36 The immunoliposomes were then radiolabeled by a remote-loading method with 99mTc, a chemical mimic of 186Re/188Re. The in vivo retention and systemic biodistribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes were investigated with nuclear imaging, postmortem stereomicroscopic fluorescent imaging and gamma counting after injection of the immunoliposomes into the surgical cavity of an enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)-expressing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer orthotopic xenograft nude rat model.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the immunoliposome platform. This platform has the capability of targeted chemo- /radionuclide therapy, or their combination with real time image-monitoring of pharmacokinetics and prediction of therapy effect. This paper reported the immunoliposome studies with the use of 99mTc and rhodamine B (Rhod) dual-labeling to synergize their advantages.

Materials and methods

Plain liposome preparation

Plain liposomes with 100-nm diameter, composed of 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt) (DSPG), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt) (Rhod-DOPE) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Alabama) and cholesterol (Calbiochem) (molar ratio, 49: 4.9: 0.1: 45) were prepared by hydration of lipid film with 300 mM ammonium sulfate in water, pH 5.1 and subsequent extrusion through nucleopore filters of different pore sizes (two times for 2 Gm, 800 nm, 400 nm and 200 nm, respectively, and then 5 times for 100 nm) at 56°C using an extruder (Northern Lipids, Vancouver, Canada).10

Conjugation of antibody (Ab) with lipid-PEG3400-NHS

The preparation of lipid-PEG-Ab used an established method of conjugating antibody to polyethylene glycol-lipid (lipid-PEG) with amide bond through N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) activation of the carboxyl group of lipid-PEG-carboxyl acid.37 The molecular ratio of antibody and lipid-PEG-NHS for conjugation, and the percentage of lipid-PEG-Ab used in liposome formulation followed the report by Elbayoumi and Torchilin.38 Three antibodies, panitumumab, bevacizumab, and nonspecific human IgG (Carimune® NF, ZLB Behring AG, Berne, Switzerland) as a control antibody, were conjugated respectively with a pegylated phospholipid containing amine-reactive NHS group, 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[succinimidyl (polyethylene glycol)] (DSPE-PEG3400-NHS) (Nanocs Inc., New York) via the amide binding as follows. Five mg of each antibody (about 0.033 µmol) was dialyzed with a Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette with a molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa (Pierce) in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer at 4°C. The dialyzed Ab concentration was then adjusted to 4 mg/ml (27 µM). DSPE-PEG3400-NHS (6.6 mg, 1.5 µmol) was dissolved with 100 µl of dimethylformamide at 4°C by vortexing and then immediately mixed with the Ab. The mixture was incubated with gentle shaking overnight at room temperature. The same preparation without Ab, which produced DSPE-PEG3400-carboxylate was used as a non-antibody control.

Immunoliposome preparation by post-insertion method

The above prepared solution of DSPE-PEG3400-Ab conjugate or non-antibody DSPE-PEG3400-carboxylate control was added to 1.2 ml of 60 mM plain liposomes (72.5 µmol total lipid) (pre-diluted with 3.7 ml of 100 mM ammonium sulfate, pH 5.1) followed by gentle vortexing. The molar ratio of total lipid/DSPE-PEG3400-NHS/Ab for immunoliposome preparation was 100: 2: 0.05. The mixture was then incubated at 60°C for 1 h. Liposomes incorporated with DSPE-PEG3400-Ab conjugate or non-antibody control were separated from other forms of Ab by ultracentrifugation at 244,000× g for 45 minutes. The supernatant was carefully aspirated without disturbing the pellets. The liposome pellets were resuspended in 100 mM ammonium sulfate and ultracentrifuged again for further purification. The final immunoliposomes were resuspended in 300 mM ammonium sulfate, pH 5.1 to a total lipid concentration of 30 mM.

The immunoliposome preparations were assayed with a fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (AKTAdesign System, Amersham Biosciences) equipped with a Superose 12 100/300 GL column. Intermediate and final samples (a few tens of microliters) containing same amount of total Ab before purification were injected into the column. The isocratic elution flow rate using phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 mobile phase was 0.8 ml/min. The chromatograms were acquired at 280 nm UV absorbance. Eluent fractions (0.3 ml) were collected and analyzed using E-80G human IgG ELISA kit and following the recommended protocol (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc., Newberg, OR).

The FPLC analysis indicated that following the reaction of DSPE-PEG3400-NHS with Ab, Ab peak height decreased and a new small and broad peak of lipid-PEG-Ab conjugates having hydrodynamic sizes larger than the original Ab was evident (Figure 2). After post-insertion of Ab conjugates and purification, the immunoliposome samples had only liposome peaks and no observable Ab peak was present in the FPLC chromatograms (Figure 2). IgG ELISA assay of the eluent fractions verified incorporation of the Ab component into the liposomes.

Figure 2.

FPLC chromatograms of DSPE-PEG-Ab conjugate, mixtures of DSPE-PEG-Ab conjugate and liposomes pre-insertion and post-insertion, and the purified immunoliposomes.

Particle sizes of the immunoliposomes were measured by a DynaPro dynamic light-scattering system (Wyatt Technology, CA). Zeta potentials were determined with a PLAS zeta-potential analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments, NY).

Preparation and in vitro stability of 99mTc-labeling immunoliposomes

The immunoliposomes and control DSPE-PEG3400-carboxylate liposomes were labeled with 99mTc using the remote loading method.31,32 Briefly, sodium 99mTc-pertechnetate (GE Healthcare) was reduced with SnCl2, and the produced 99mTc(V) was complexed with N, N-bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-N’, N’-diethyl-ethylenediamine (BMEDA) (ABX GmbH, Germany). Prior to 99mTc-labeling the liposomes were loaded onto a Sephadex-G25 column and eluted with PBS, pH 7.4 to remove extra-liposomal ammonium sulfate and to create an ammonium sulfate/pH gradient. Then the 99mTc-BMEDA was mixed with the ammonium/pH gradient liposomes in PBS, pH 7.4 and incubated at 39°C for 1 h. The 99mTc-liposomes were separated from any 99mTc-BMEDA not associated with the liposomes using another Sephadex-G25 column and elution with PBS, pH 7.4. In vitro stabilities of prepared 99mTc-liposomes was investigated using the spin column separation method.33,39

Breast cancer xenograft rat model

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For all procedures, the rats were anesthesized by inhalation of 1–3% isoflurane in 100% oxygen. The engineered EGFP-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells,40 gifted by Dr. Luzhe Sun (UT Health Science Center at San Antonio), were cultured in Leibovitz’s L15 medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% 100× Pen-Strep solution. The cells were harvested by digestion with mixture of 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA when the culture reached approximately 80% confluency and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes at 5°C. Breast cancer orthotopic xenograft model was set up by inoculating 7 million engineered EGFP-expressing MDA-MB-231 cells resuspended in 0.2 ml saline into the mammary fat pad of left breast of 5-wk-old female rnu/rnu nude rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). The tumor take rate was about 80% at 3 weeks after tumor cell inoculation.

Lumpectomy surgery and intracavitary injection of 99mTc-immunoliposomes

The lumpectomy dissection, similar to previously described method,12 was performed in anesthesized rats 24 days after tumor cell inoculation. The skin above tumor was separated after making a transverse cutaneous incision directly superior to the tumor. The majority of tumor (tumor volume: 3.88±1.66 cm3) was excised with a small volume (~ 0.1 cm3) of tumor remnant deliberately left in the bottom of tumor bed in the cavity to mimic a positive surgical margin. Then saline for injection was used to wash the cavity and the cutaneous incision was closed with interrupt suture. Surgical adhesive (Vetbond™, 3M, MN) was applied to help seal the skin incision.

Two days after surgery, fluid in the cavity, if present in a significant volume, was gently aspirated using a syringe with 25G needle. One ml of each freshly prepared immunoliposome formulation, including the non-antibody control liposomes, human IgG-, bevacizumab- and panitumumab-liposomes (30 µmol of total lipids) was labeled with 99mTc. Then each rat (4–5 rats per group) was anesthesized and intracavitarily injected with 0.5 ml of purified 99mTc-liposomes in PBS, pH 7.4 (111–159 MBq, 3.2 – 3.8 µmol total lipids). The cavity area was gently massaged to facilitate the homogeneous distribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes inside the cavity space. Surgical adhesive was applied to the injection site to prevent drug leakage if necessary.

Nuclear imaging and biodistribution determination

Planar gamma camera images of the anesthesized rat in the supine position were acquired at various times post-99mTc-immunoliposome injection using a dual headed micro-SPECT/CT (XSPECT FLEX, Gamma Medica Ideas, CA) equipped with parallel hole collimators. A vial of known amount of 99mTc as reference standard was located in the image field of view. The acquisition time was 1 minute at baseline, 1 h, 2 h and 4 h post-injection, 5 minutes at 20 h, and 10 minutes at 44 h. Between imaging sessions, the animals were placed individually in metabolic cages to collect urine and feces. The percentage of injected dose (%ID) of 99mTc in surgical cavity was quantitatively determined by drawing regions-of-interest (ROI) in the images and comparing the ROI activity with the radioactive standard measured together with the animal. The 1-mm pinhole collimator SPECT images focused on the surgical cavity with an approximately 7 cm field of view were also acquired following planar imaging at 2 h (15 s/projection, 32 projections) and 20 h (45 s/projection, 32 projections) for two rats in each group.

Following nuclear imaging at 44 h, any intracavitary fluid, if present, was aspirated using a syringe. Saline (1 ml) was injected into the cavity and then aspirated to collect the whole fluid in the surgical cavity. Blood samples were collected through cardiac puncture. The rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia. The skin above surgical cavity and the lymph nodes surrounding the cavity, including superficial cervical lymph nodes (SCLNs), axillary lymph node and lateral thoracic lymph node (ALNs) were exposed. Stereofluorescent microscopic images were acquired using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica MZ16 FA) coupled with a digital camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-ERA-1394) and Image-ProPlus analytical imaging software focusing on the open cavity and exposed lymph nodes. Then these tissues and other major organs were harvested, and counted with an automatic gamma counter (Wallac WIZARD 3" Automatic Gamma Counter) along with the 99mTc standard sample for radioactivity measurement.

Histologic examination of peripheral lymph nodes

The dissected peripheral lymph nodes, categorized as SCLNs and ALNs, were separately fixed in 10% (V/V) neutral buffered formalin and embedded with paraffin. Histological sections of 5 µm thickness of the SCLNs and ALNs of each animal were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histopathologic examination.

Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and graphed using Origin 7.5 software (Origin Lab Cooperation, Northampton, MA). The inter-group differences in data, including %ID in cavity area derived from planar images at different times, %ID and %ID/g of organ/tissue derived from gamma counting were assessed with independent-samples t test for two groups and one-way ANOVA for four group comparisons using SPSS10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical analysis of significant difference used 95% confidence interval as standard (P < 0.05).

Results

Immunoliposome Characterization

Particle sizes of the immunoliposomes and non-antibody control liposomes were larger than the original liposomes (diameter: 162.2 ~ 171.1 nm versus 128.4 nm), indicating that the insertion of lipid-PEG-Ab conjugates or lipid-PEG-carboxylate increased the hydrodynamic diameter of liposomes. The immunoliposomes and non-antibody control liposomes had similar zeta potentials as the original liposomes (−4.32 ~ −5.45 mV versus −6.61 mV). Since the liposome bilayer had a thickness of 4 nm 41 and a lipid density of about 0.983 g/mol,42 if we assume the size of the phospholipid core is unchanged before and after insertion, based on the Ab concentration of immunoliposomes determined by the ELISA kit, the numbers of Ab molecules of each immunoliposome particle were estimated to be 36, 15 and 36 for non-specific human IgG, panitumumab and bevacizumab, respectively.

Labeling efficiencies of immunoliposomes and non-antibody control liposomes with 99mTc were 53% ~ 66%. Particle sizes and zeta potentials (−5.01 to −5.94 mV) of labeled immunoliposomes were similar to those before radiolabeling. Investigation of in vitro stability of the 99mTc-liposomes by spin column separation indicated that about 90% of 99mTc was associated with liposomes after 96 h incubation in PBS, pH 7.4 at 25°C, and > 70% after 96 h of incubation in 50% (V/V) PBS, pH 7.4/fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C.

Intracavitary retention of 99mTc-immunoliposomes by nuclear imaging

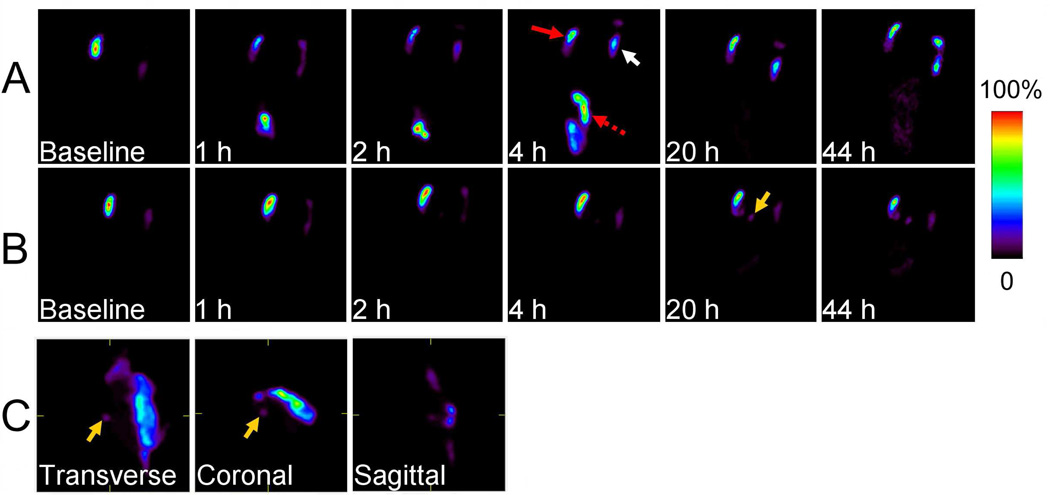

From ROI analysis of planar images (Figure 3), there was sustained surgical cavity retention of all 99mTc-liposomes formulations. The %ID in cavity decreased more rapidly during the first 4 h post-injection for all liposome groups and then continued to gradually decrease at different rates depending on the formulation. For all liposome groups, there was an averaged 36.4 %ID retained in the cavity area at 44 h, with panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposome groups having higher local retention of radioactivity over 44 h (Figure 4a). Values of %ID in cavity were 60.6±40.1 (n=4), 54.3±43.5 (n=5), 75.7±38.6 (n=5) and 83.6±22.1 (n=5) at 4 h for the non-antibody control, human IgG-, panitumumab-and bevacizumab-liposome groups, respectively; and 37.3±38.4, 33.1±39.9, 28.0±17.5 and 48.4±20.7 at 44 h. However, these differences had no statistical significance among the four groups because the intracavitary retention of 99mTc with time varied within each group.

Figure 3.

Representative lateral planar gamma camera images and SPECT images of rats intracavitrarily injected with 99mTc-immunoliposomes post-lumpectomy. A vial of 99mTc standard (white arrow) was measured concomitantly with the rat for the planar gamma camera images. A) Rapid clearance of radioactivity from surgical cavity (red arrow) and excretion through large intestine (dashed red arrow), B) High retention of radioactivity in surgical cavity. C) SPECT image focusing on the cavity at 20 h. Accumulation of radioactivity in the draining lymph node was detectable (yellow arrow).

Figure 4.

Pharmacokinetic curves of 99mTc labeled immunoliposomes in surgical cavity post-injection. a) The averaged %ID of each immunoliposome group; b) The averaged %ID of high intracavitary retention subset and low intracavitary retention subset of total rats.

Further, the experimental animals intracavitarily injected with 99mTc-immunoliposomes can be characterized by two distinct subsets, according to the level of %ID in the cavity area or clearance status (Figure 4b). The high %ID retention subset displayed a slow and gradual radioactivity clearance from surgical cavity, with 79.0±10.3 %ID and 56.7±17.6 %ID remaining in the cavity at 20 h and 44 h, respectively. In contrast, for the low %ID retention subset (clearance > 50 %ID), rapid clearance of 99mTc from cavity occurred within 2 hours, or occasionally was observed for only one rat during the 4 h to 20 h interval post-injection; only 14.0±12.1 %ID and 8.5±7.1 %ID were remained in the cavity at 20 h and 44 h, respectively. The high %ID retention subset was prevalent in bevacizumab- and panitumumab-liposome groups and their animal ratios were higher than those of non-antibody control and non-specific human IgG-liposome groups (high %ID subset/ total animal ratio: 4/5, 3/5 versus 2/4, 2/5, respectively).

Systemic organ distribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes by nuclear imaging

Planar images (Figure 3) displayed the systemic organ distribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes in addition to the surgical cavity. The cleared radioactivity from cavity was metabolized quickly and excreted into feces and urine. Liver and spleen were sometimes recognizable, but their %ID values were much lower than that of cavity area, with ≤ 4.3 %ID in liver and ≤ 3.5 %ID in spleen for all time points within 24 h post-injection. The highest values in liver and spleen at 44 h were 8.2 %ID and 5.4 %ID, respectively. For the low %ID retention subset, most of the activity that abruptly cleared from surgical cavity within 2 h post-injection was also quickly excreted into the large intestinal tract and then excreted from body, similar to previous results of different types of plain liposomes in a similar animal model having smaller tumor sizes.12 Lymph nodes surrounding the surgical cavity, including SCLNs and ALNs, in which radioactivity accumulated, could also be detected from planar and SPECT images (Figures 3B and 3C) in several rats of both the control and immunoliposome groups. For the high intracavitary retention subset, the %ID in draining lymph nodes gradually increased by 20 h and continued to increase but at a slower rate to 44 h (Figure 5h).

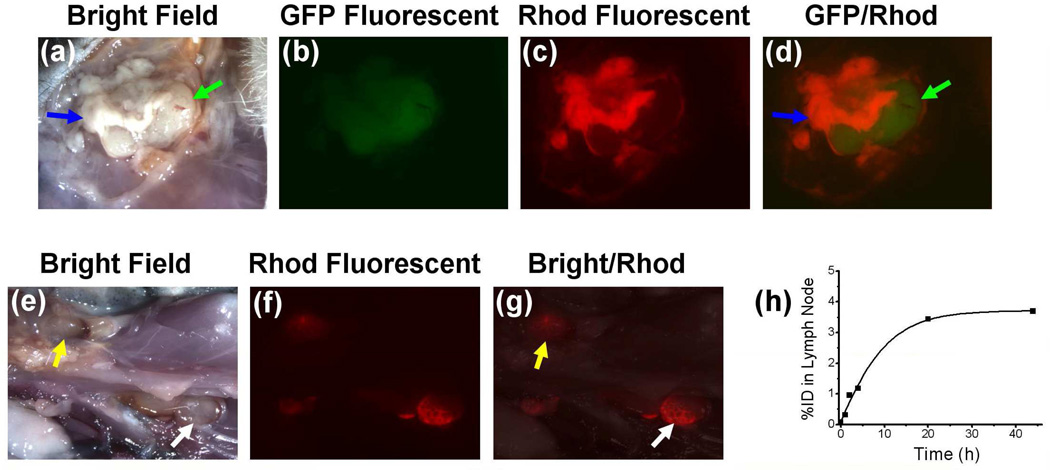

Figure 5.

Stereomicroscopic fluorescent images of open surgical cavity and peripheral lymph nodes 44 h post intracavitary injection of 99mTc labeled panitumumab-liposomes containing Rhod-DOPE tracer. The location of residual tumor and peripheral lymph nodes were identified by white light images (a and e). The fused GFP/Rhodamine fluorescent image (d) displayed the concentration of Rhod-DOPE in residual tumor, especially in the remnant (blue arrow) other than the regrowing region (green arrow). The fused white light/Rhoadamine fluorescent image (g) displayed a high concentration of Rhod-DOPE in axillary lymph node (yellow arrow) and lateral thoracic lymph node (white arrow) of a rat from panitumumab-liposome group with high intracavitary retention of radioactivity. Change of %ID in the lateral thoracic lymph node (h) was obtained from the corresponding lateral planar gamma images.

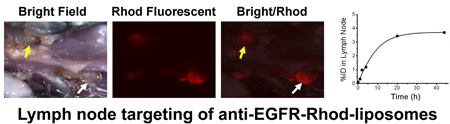

Locoregional retention of 99mTc-immunoliposomes by stereofluorescent microscopic imaging

By visual inspection during dissection and GFP fluorescent imaging, most of the residual tumors were found to be much larger than the original tumor remnant, indicating a significant regrowth of the positive surgical margin in 4 days. From stereofluorescent microscopic images of panitumumab-liposome group, the red Rhod-fluorescence was concentrated at the incision area of tumor rather than the surface of regrowing tumor remnant covered by fibroblast layer and surrounding muscle surface (Figure 5). This observation reflects the relative accumulation of panitumumab-liposomes on the tumor cells, while fibroblast layer tended to be the barrier of the specific targeting. This observation indicates a challenge of targeted cancer therapy, while providing insights on treatment options when confronted with the similar situation clinically. The fluorescent distribution and intensity acquired under the same instrument parameters varied significantly in each group, as reported for the intracavitarily retained radioactivity. The relative intensity of fluorescence corresponded with the level of %ID in the cavity. Lymph nodes surrounding the cavity were also distinguishable from the fluorescent images. Several rats of panitumumab-liposome group, but none of the control groups, also displayed strong lymph node targeting of red fluorescence, as shown in typical images of this group in Figure 5.

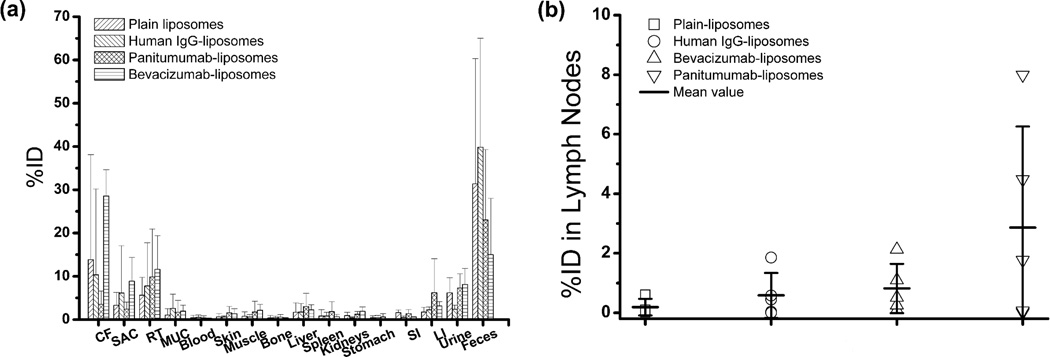

Biodistribution of 99mTc-immunoliposomes by gamma counting

The %ID of 99mTc-immunoliposomes distributed in cavity samples, other important organs, feces and urine are shown in Figure 6. The %ID in cavity was predominately located in residual tumor and skin above the cavity. The averaged %ID in residual tumor of panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposome groups were higher than the non-antibody control and non-specific human IgG-liposome groups (10.29±10.98%, 11.97±7.67% versus 5.63±4.12%, 6.81±7.99%, respectively), but without statistical significance.

Figure 6.

Percentage of injected dose (%ID) of 99mTc encapsulated liposomes per organ/tissue at 44 h post-intracavitary injection. A) Samples from surgical cavity and other major organs, B) Lymph nodes surrounding surgical cavity, data from each animal were displayed together with the mean value of each group. Abbreviation: CF, cavity fluid; SAC, skin above cavity; RT, residual tumor; MUC, muscle under cavity; SI, small intestine; LI, large intestine; total LNs, total lymph nodes, including SCLNs and ALNs.

The weights of draining lymph nodes, SCLNs or ALNs, had no statistical difference among the four liposome groups. The radioactivity was significantly concentrated in these draining lymph nodes surrounding surgical cavity. The %ID/g of LNs were much higher than that of normal muscle (6 – 1571 fold). Panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposome groups had higher averaged %ID in combined SCLNs and ALNs than the control and human IgG-liposome groups (2.86, and 0.82 versus 0.19, and 0.36, respectively).

The %ID/g values of blood and vital organs were at low levels at 44 h post intracavitary injection (Table 1). The 99mTc retention in liver and kidneys was 0.39±0.38 %ID/g and 0.73±0.38 %ID/g for panitumumab-liposome group, 0.26±0.15 %ID/g and 1.21±0.65 %ID/g for bevacizumab-liposome group. The highest %ID/g in kidneys was from bevacizumab-liposome group (2.15 %ID/g). The highest %ID/g in liver was from panitumumab-liposome group (0.86 %ID/g).

Table 1.

Percentage of 99mTc injection dose per gram (%ID/g) of organ at 44 h post-intracavitary injection (mean±SD).

| Organ | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain liposome | Human IgG-liposome | Bevacizumab-liposome | Panitumumab-liposome | |

| Blood | 0.05±0.07 | 0.06±0.07 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.05±0.06 |

| SAC | 5.01±4.02 | 10.1±19.24 | 6.94±3.9 | 2.65±1.55 |

| RT | 7.87±8.47 | 21.02±30.88 | 7.33±1.47 | 21.92±32.24 |

| MUC | 3.8±4.92 | 11.47±13.94 | 9.72±7.76 | 4.71±7.69 |

| Skin | 0.03±0.04 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.07±0.06 | 0.08±0.08 |

| Muscle | 0.01±0.02 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.03±0.04 |

| Femur | 0.02±0.03 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.04±0.04 |

| Liver | 0.19±0.22 | 0.21±0.24 | 0.52±0.59 | 0.39±0.38 |

| Spleen | 1.96±3.54 | 2.36±2.61 | 1.16±0.95 | 4.11±5.15 |

| Kidneys | 0.55±0.40 | 0.30±0.19 | 0.95±0.74 | 0.73±0.38 |

| Stomach | 0.08±0.07 | 0.11±0.16 | 0.05±0.07 | 0.29±0.45 |

| SI | 0.15±0.05 | 0.08±0.05 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.20±0.16 |

| LI | 0.37±0.23 | 0.33±0.12 | 0.49±0.21 | 1.10±1.61 |

| Bladder | 0.08±0.03 | 0.08±0.09 | 0.31±0.39 | 0.13±0.12 |

| Heart | 0.02±0.03 | 0.02±0.02 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.03 |

| Lung | 0.05±0.05 | 0.05±0.05 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.06±0.06 |

Abbreviation: SAC, skin above cavity; RT, residual tumor; MUC, muscle under cavity; SI, small intestine; LI, large intestine.

The %ID in feces was correlated to %ID in cavity for all rats, exhibiting a smooth single exponential decay curve (data not shown), while %ID in urine showed irregular change with %ID in cavity. The excretion by intestinal tract was the predominant metabolic route of rapidly cleared 99mTc-liposomes.

The %ID values in each organ of the high cavitary retention subset of all rats were generally much higher than that of the low cavitary retention subset. The low cavitary retention subset had only 0.15±0.21 %ID in total LNs, however, the high cavitary retention subset had a higher value of 1.80±2.42 %ID in total LNs. According to our previous theoretical human LN dose calculations,19 we choose 0.4 %ID in total LNs or 0.2 %ID in SCLNs or ALNs, which may ensure an effective radiotherapeutic dose of 186Re/188Re-liposomes to LNs following intracavitary injection of acceptable amount of 186Re/188Re-liposomes, as criteria to distinguish high radioactivity focus and low radioactivity focus in LNs. Most animals of low cavitary retention subset had low radioactivity focus in LNs (animal ratio: 6/8). On the other hand, many animals in the high cavitary retention subset had high radioactivity focus in LNs (animal ratio: 8/11). The averaged %ID in total LNs of panitumumab-liposome group was much higher than other groups. The control plain liposome group had the lowest averaged %ID in total LNs.

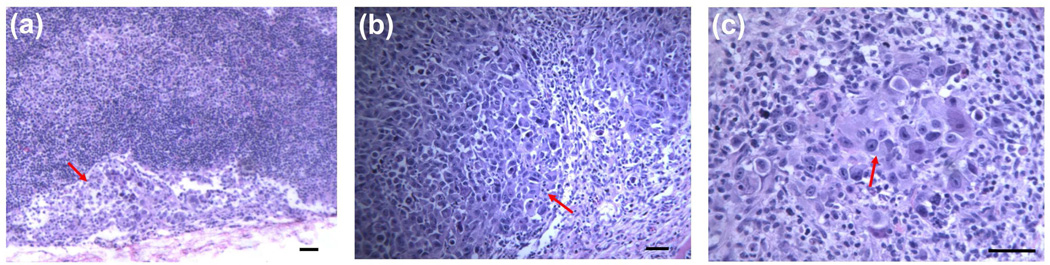

Histological results of peripheral lymph nodes

The histology of peripheral lymph nodes surrounding the cavity was examined. Extranodal extension of breast cancer cells was found in several lymph node slides (Figure 7a), intranodal invasion of the breast cancer cells presented in many other lymph nodes (Figures 7b and 7c), whereas the other lymph nodes displayed no invasion or very limited isolated presence of breast cancer cells. The intranodal metastatic breast cancer cells mostly aggregated in the subcapsular area, but sometimes also showed aggressive diffusion to efface partial architecture of normal lymph node.

Figure 7.

Representative H&E stained histologic images of peripheral lymph nodes surrounding surgical cavity after excision from rats with breast tumor xenografts showing micrometastasis. a) extranodal extension of big tumor cells with light blue stained cytoplasm (red arrow) in a ALN (small lymphocytes stained in deep blue color), original zoom 100×, b) diffuse infiltrate of big tumor cells (red arrow) invaded in subcapsular area and effaced partial normal architecture in a SCLN, original zoom 120×, c) big tumor cells (red arrow) colonized in the LN interior and admixed with lymphocytes, original zoom 240×.

The LNs in high radioactivity focus status generally had a high proportion of LN metastasis, with slide ratios of 4/4, 4/4 and 3/4, respectively for the panitumumab-, bevacizumab-liposome groups and two control groups, but LNs from animals with low intracavitary retention had lower lymph node metastasis, with a slide ratio of only 5/26. These results suggest that the LN concentration of radioactivity was related to the metastasis status as well as the extent of intracavitary %ID retention. Though the sample number was limited, three LNs with metastasis in panitumumab-liposome group at 44 h post-injection had much higher %ID values (1.7, 4.5 and 7.4, compared to 0.8, the maximum %ID in LNs of the two control groups), thus suggesting that the active targeting of panitumumab-liposomes towards metastatic tumor contributed to the increased %ID in the LNs in this group.

Discussion

The post-lumpectomy brachytherapy by intracavitary injection of immunoliposomes encapsulating therapeutic radionuclide, 186Re or 188Re, may afford an alternative approach to current treatments of early stage breast cancer patients.12,19 The emerging advantages of this new treatment approach include the simultaneous eradication of residual tumor cells remaining in the cavity and in draining lymph nodes, decreased toxicity to normal tissue and the capability of synchronous chemoradiation using the same liposome carriers 43,44 or combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. The coating of tumor specific antibody molecules on the liposome surface could further improve the active targeting ability of liposomes towards tumor tissue or cells. We investigated the feasibility of using EGFR targeted panitumumab-liposomes and VEGF targeted bevacizumab-liposomes in this strategy in an orthotopic human breast cancer xenograft nude rat model with positive tumor margin following lumpectomy. To investigate breast cancer therapy with the targeted liposomal therapeutic agents, established methods of bioconjugation and preparation of immunoliposomes were used. 34–38 Serial purifications with dialysis and ultracentrifugation were performed to ensure purity of immunoliposomes. FPLC method was used to characterize bioconjugation reaction and lipid-PEG-Ab's insertion to pre-manufactured liposomes (Figure 2). The amounts of antibody molecules linked to each liposome particle were assayed by ELISA.

The immunoliposomes, estimated to have 15 panitumumab molecules or 35 bevacizumab molecules per nanoparticle, had slightly increased particle sizes and similar surface zeta potential compared to the plain liposomes. The immunoliposomes were stably radiolabeled with 99mTc using mild conditions. Animal studies indicated 99mTc-immunoliposomes had good local retention after intracavitary injection, except in those few animals with rapid fecal excretion of cleared radioactivity, and thus avoided high radiation dose and toxicity to vital organs. The residual tumor regrew rapidly in the four days after surgery and the new fibroblast surface of proliferating tumor may have retarded the adsorption and delivery of a higher dose of radiolabeled immunoliposomes inside the tumor. Due to the restriction of the presence of relatively large-sized tumors adjacent to thoracic wall in this study, the lumpectomy we could perform in this rat model without complications led to the actual area of the positive margin probably exceeding the residual tumor nodule. The surgical wound could also stimulate the progression of positive margin.45 It is worthy to note the 2 mm or 5 mm effective therapeutic distances of 186Re or 188Re 19 may tolerate weak attachment and accumulation of 186Re/188Re labeled immunoliposomes on small zone of intact tumor surface. But more importantly, in practice the lumpectomy for human early breast cancer is aggressive and should result in the presence of only a very thin positive margin or isolated tumor cells. Thus, the fast regrowth of tumor and inefficient coverage of tumor by therapeutic liposomes observed in our animal model will be avoided in human studies.

The large variation of intracavitary retention of 99mTc with time for all four groups suggested that the retention was dependent on the specific physiological status of the surgical site. Accordingly, all animals could be divided into two subsets with high or low intracavitary retention, based on the distinct characteristics of curves of %ID retention in surgical cavity with time. This phenomenon also occurred in our previous study with different types of plain liposomes.12 A high intracavitary retention can guarantee a high radiation dose deposition and an effective eradication of residual positive margin or isolated tumor cells in the cavity area. However, a low intracavitary retention will decrease the efficacy of treatment, though the systemic toxicity appears to be minimal due to the simultaneously rapid metabolism of cleared radioactivity. The higher ratios of animals in high %ID retention subset in panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposome groups compared with the two controls may reflect the active EGFR targeting or VGFR targeting of immunoliposomes in the surgical cavity with positive margin which caused the blockage of rapid macroscopic vascular absorption of 99mTc-immunoliposomes and delayed clearance.

The orthotopic breast cancer rat model used in this study has obvious physiological differences compared with human early stage breast cancer. The rapid clearance of radioactive liposomes from cavity that occurred in the rat model is probably due to the inability to surgically excise tumor tissue invading the thoracic wall without complications. However, this thoracic wall involvement is less likely to occur in human subjects with early stage breast cancer, and thus the rate of rapid clearance may be much lower. In fact, the most frequent complication of human breast cancer surgery is the excessive fluid accumulation in cavity, which results in the incidence of seroma at high rate.46,47 In addition, considering the low systemic toxicity of radiotherapeutic liposomes after intracavitary injection, the incidence of low intracavitary retention of liposomes could be a limiting but not overwhelming factor for the potential application of this regime.

Due to the inevitable difference of primary tumor status, surgical extent and subsequent wound healing process, the surgical sites had a complicated individualized physiological status after the lumpectomy. The varying sizes of residual tumor regrowth four days post-surgery prevented the use of a single index, like %ID or %ID/g of residual tumor, to accurately evaluate the targeting of immunoliposomes. Alternatively, stereofluorescent microscopic imaging provided a direct observation of Rhod-DOPE containing liposomes distributed inside the surgical cavity. When the immunoliposomes were highly retained in the cavity, panitumumab-liposome group had much higher relative fluorescent intensity at the residual tumor surface compared to the growing fibroblast enriched tumor surface and muscle at cavity bottom in contrast to the control liposome groups, indicating the active targeting of immunoliposomes towards breast cancer tumor tissue.

The liposome carried radioactivity was concentrated in the draining LNs surrounding the surgical cavity. The level of %ID in draining LNs was dependent on the radioactivity retention level in surgical cavity and related to the metastasis status. The panitumumab-liposomes actively targeted the draining metastatic LNs and thus remarkably enhanced the LN focus of radiation dose, which could lead to more effective eradication of the metastatic tumor cells. Recent studies have suggested that lymphangiogenesis can contribute to metastasis of many types of cancer.48,49 It was reported that MDA-MB-231 cells, which express VEGF-C promoted lymphangiogenesis in a mammary fat pad xenograft mouse model of breast cancer, and intravenously injected bevacizumab did not significantly inhibit lymph node metastasis because of the lack of lymphatic vessel compression.50 In our study, the lymph node focus of 99mTc labeled bevacizumab-liposomes was not significant higher than that of control liposomes, especially the non-specific IgG-liposomes, implying the bevacizumab incorporation has limited function to enhance liposome targeting to metastatic LNs, however, it can benefit the retention and residual tumor targeting of liposomes inside the cavity.

Conclusion

The liposomes comprised of DSPC/DSPG/cholesterol with ammonium sulfate in the interior space can be functionalized with lipid-pegylated tumor specific targeting antibodies, panitumumab or bevacizumab, and further effectively labeled with 99mTc, a chemical mimic of therapeutic radionuclides, 186Re/188Re by remote loading. After the 99mTc labeled panitumumab- and bevacizumab-liposomes were intracavitarily injected into the surgical cavity in an orthotopic breast cancer xenograft rat model following tumor removal to simulate positive surgical margin, there was high intracavitary retention of the 99mTc-activity. Panitumumab-liposomes also had higher %ID in the metastatic lymph nodes. The cleared 99mTc-activity was metabolized quickly and exerted no significant systemic toxicity. The results indicated that liposomes carrying therapeutic radionuclides and modified with tumor specific targeting panitumumab and bevacizumab molecules have the increased potential compared to non specific targeting liposomes to be used for enhanced post-lumpectomy focal radiotherapy to eradicate locally remaining and peripheral lymph node metastatic breast cancer cells with low systematic toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors would like to thank Dr. Vladimir Torchilin at Northeastern University, Boston, MA, for technical support on preparation of immunoliposomes. This study was sponsored by Susan G. Komen for the Cure@ research grant, BCTR0707169 and partly supported by NIH/NCI grant, R01 CA131039. Stereomicroscopic fluorescent images were generated in the Core Optical Imaging Facility which was supported by UTHSCSA, NIH-NCI P30 CA54174 (San Antonio Cancer Institute), NIH-NIA P30 AG013319 (Nathan Shock Center), and (NIH-NIA P01AG19316).

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

REFERENCES

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest AP, Stewart HJ, Everington D, Prescott RJ, McArdle CS, Harnett AN, Smith DC, George WD. Randomised controlled trial of conservation therapy for breast cancer: 6-year analysis of the Scottish trial Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group. Lancet. 1996;348:708–713. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liljegren G, Holmberg L, Bergh J, Lindgren A, Tabar L, Nordgren H, Adami HO. 10-Year results after sector resection with or without postoperative radiotherapy for stage I breast cancer: a randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:2326–2333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van de Steene J, Vinh-Hung V, Cutuli B, Storme G. Adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer: effects of longer follow-up. Radiother. Oncol. 2004;72:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veronesi U, Marubini E, Mariani L, Galimberti V, Luini A, Veronesi P, Salvadori B, Zucali R. Radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in small breast carcinoma: long-term results of a randomized trial. Ann. Oncol. 2001;12:997–1003. doi: 10.1023/a:1011136326943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma G, Anabousi S, Ehrhardt C, Ravi Kumar MN. Liposomes as targeted drug delivery systems in the treatment of breast cancer. J. Drug Target. 2006;14:301–310. doi: 10.1080/10611860600809112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Current trends in liposome research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;605:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-360-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrington KJ, Rowlinson-Busza G, Syrigos KN, Uster PS, Vile RG, Stewart JS. Pegylated liposomes have potential as vehicles for intratumoral and subcutaneous drug delivery. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:2528–2537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao A, Phillips WT, Goins B, Zheng X, Sabour S, Natarajan M, Ross WF, Zavaleta C, Otto RA. Potential use of drug carried-liposomes for cancer therapy via direct intratumoral injection. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;316:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang SX, Bao A, Herrera SJ, Phillips WT, Goins B, Santoyo C, Miller FR, Otto RA. Intraoperative 186Re-liposome radionuclide therapy in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft positive surgical margin model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:3975–3983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French JT, Goins B, Saenz M, Li S, Garcia-Rojas X, Phillips WT, Otto RA, Bao A. Interventional therapy of head and neck cancer with lipid nanoparticle-carried rhenium 186 radionuclide. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010;21:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Goins B, Phillips WT, Saenz M, Otto PM, Bao A. Post-lumpectomy intracavitary retention and lymph node targeting of 99mTc-encapsulated liposomes in nude rats with breast cancer xenograft. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;130:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1309-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborne MP, Richardson VJ, Jeyasingh K, Ryman BE. Radionuclide-labelled liposomes—a new lymph node imaging agent. Int. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1979;6:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(79)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker RJ, Hartman KD, Sieber SM. Lymphatic absorption and tissue disposition of liposome-entrapped [14C]adriamycin following intraperitoneal administration to rats. Cancer Res. 1981;41:1311–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangat S, Patel HM. Lymph node localization of nonspecific antibody-coated liposomes. Life Sci. 1985;36:1917–1925. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oussoren C, Storm G. Liposomes to target the lymphatics by subcutaneous administration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;50:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghimi M, Moghimi SM. Lymphatic targeting of immuno-PEG-liposomes: evaluation of antibody-coupling procedures on lymph node macrophage uptake. J. Drug Target. 2008;16:586–590. doi: 10.1080/10611860802228905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips WT, Goins BA, Bao A. Radioactive liposomes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:69–83. doi: 10.1002/wnan.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hrycushko BA, Li S, Shi C, Goins B, Liu Y, Phillips WT, Otto PM, Bao A. Postlumpectomy focal brachytherapy for simultaneous treatment of surgical cavity and draining lymph nodes. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011;79:948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition strategies in oncology. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2004;11:689–708. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baselga J, Arteaga CL. Critical update and emerging trends in epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:2445–2459. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston JB, Navaratnam S, Pitz MW, Maniate JM, Wiechec E, Baust H, Gingerich J, Skliris GP, Murphy LC, Los M. Targeting the EGFR pathway for cancer therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:3483–3492. doi: 10.2174/092986706779026174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang XD, Jia XC, Corvalan JR, Wang P, Davis CG. Development of ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-EGF receptor monoclonal antibody, for cancer therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2001;38:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer,vascular ,rheumatoid and other disease. Nat. Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, Armanini M, Gillett N, Phillips HS, Ferrara N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature. 1993;362:841–844. doi: 10.1038/362841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu JY, Wakelee HA. Monoclonal antibodies targeting vascular endothelial growth factor: current status and future challenges in cancer therapy. BioDrugs. 2009;23:289–304. doi: 10.2165/11317600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, Dickler M, Cobleigh M, Perez EA, Shenkier T, Cella D, Davidson NE. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao A, Goins B, Klipper R, Negrete G, Phillips WT. Direct 99mTc labeling of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) for pharmacokinetic and non-invasive imaging studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;308:419–425. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goins B, Bao A, Phillips WT. Techniques for loading technetium-99m and rhenium-186/188 radionuclides into pre-formed liposomes for diagnostic imaging and radionuclide therapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;606:469–491. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-447-0_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Goins B, Phillips WT, Bao A. Remote-loading labeling of liposomes with 99mTc- BMEDA and its stability evaluation: effects of lipid formulation and pH/chemical gradient. J. Liposome Res. 2011;21:17–27. doi: 10.3109/08982101003699036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen TM, Sapra P, Moase E. Use of the post-insertion method for the formation of ligand- coupled liposomes. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2002;7:889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreira JN, Ishida T, Gaspar R, Allen TM. Use of the post-insertion technique to insert peptide ligands into pre-formed stealth liposomes with retention of binding activity and cytotoxicity. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:265–269. doi: 10.1023/a:1014434732752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohl Kullberg E, Bergstrand N, Carlsson J, Edwards K, Johnsson M, Sjöberg S, Gedda L. Development of EGF-conjugated liposomes for targeted delivery of boronated DNA-binding agents. Bioconjug. Chem. 2002;13:737–743. doi: 10.1021/bc0100713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 1996. pp. 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin Vladimir P. Enhanced accumulation of long-circulating liposomes modified with the nucleosome-specific monoclonal antibody 2C5 in various tumours in mice: gamma-imaging studies. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2006;33:1196–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chonn A, Semple SC, Cullis PR. Separation of large unilamellar liposomes from blood components by a spin column procedure: towards identifying plasma proteins which mediate liposome clearance in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1070:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandyopadhyay A, Wang L, Chin SH, Sun LZ. Inhibition of skeletal metastasis by ectopic ERalpha expression in ERalpha-negative human breast cancer cell lines. Neoplasia. 2007;9:113–118. doi: 10.1593/neo.06784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang C, Mason JT. Geometric packing constraints in egg phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:308–310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman GC, Huang C. Structural studies on phophatidylcholine-cholesterol mixed vesicles. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3363–3370. doi: 10.1021/bi00686a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soundararajan A, Bao A, Phillips WT, McManus LM, Goins BA. Chemoradionuclide therapy with 186Re-labeled liposomal doxorubicin: toxicity, dosimetry, and therapeutic response. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2011;26:603–614. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soundararajan A, Dodd GD, 3rd, Bao A, Phillips WT, McManus LM, Prihoda TJ, Goins BA. Chemoradionuclide therapy with 186Re-labeled liposomal doxorubicin in combination with radiofrequency ablation for effective treatment of head and neck cancer in a nude rat tumor xenograft model. Radiology. 2011;261:813–823. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mannino M, Yarnold J. Effect of breast-duct anatomy and wound-healing responses on local tumour recurrence after primary surgery for early breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:425–429. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez EA, Saltzstein EC, Riedner CS, Nelson BK. Seroma formation following breast cancer surgery. Breast J. 2003;9:385–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuroi K, Shimozuma K, Taguchi T, Imai H, Yamashiro H, Ohsumi S, Saito S. Pathophysiology of seroma in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2005;12:288–293. doi: 10.2325/jbcs.12.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stacker SA, Achen MG, Jussila L, Baldwin ME, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis and cancer metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:573–583. doi: 10.1038/nrc863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sleeman J, Schmid A, Thiele W. Tumor lymphatics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2009;19:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui J, Funahashi Y, Uenaka T, Watanabe T, Tsuruoka A, Asada M. Multi-kinase inhibitor E7080 suppresses lymph node and lung metastases of human mammary breast tumor MDA-MB-231 via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor (VEGF-R) 2 and VEGF-R3 kinase. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:5459–5465. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]