Abstract

Background

A functional polymorphism in the inhibitory IgG-Fc receptor FcγRIIB influences intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) response in Kawasaki Disease (KD) a vasculitis preferentially affecting the coronary arteries in children. We tested the hypothesis that the polymorphisms in the activating receptors (Fcγ RIIA, Fcγ RIIIA and Fcγ RIIIB) also influence susceptibility, IVIG treatment response, and coronary artery disease (CAD) in KD patients.

Methods and Results

We genotyped polymorphisms in the activating FcγRIIA, FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIIB genes using pyrosequencing in 443 KD patients, including 266 trios and 150 single parent-child pairs, in northwest US and genetically determined race with 155 ancestry information markers. We used the FBAT program to test for transmission disequilibrium and further generated pseudo-sibling controls for comparisons to the cases. The FcγRIIA-131H variant showed an association with KD (p = 0.001) with ORadditive = 1.51 [1.16–1.96], p = 0.002) for the primary combined population, which persisted in both Caucasian (p = .04) and Asian (p = .01) subgroups and is consistent with the recent genome-wide association study. We also identified over-transmission of FcγRIIIB-NA1 among IVIG non-responders (p = 0.0002), and specifically to Caucasian IVIG non-responders (p = 0.007). Odds ratios for overall and Caucasian non-responders were respectively 3.67 [1.75–7.66], p = 0.0006 and 3.60 [1.34–9.70], p = 0.01. Excess NA1 transmission also occurred to KD with CAD (ORadditive = 2.13 [1.11–4.0], p = 0.02).

Conclusion

A common variation in FcγRIIA is associated with increased KD susceptibility. The FcγRIIIB-NA1, which confers higher affinity for IgG compared to NA2, is a determining factor for treatment response. These activating FcγRs play an important role in KD pathogenesis and mechanism of IVIG anti-inflammatory.

Keywords: coronary disease, pediatrics, Kawasaki disease, IVIG treatment response, FcγR

Introduction

Human pooled intravenous immunoglobin (IVIG) is used in high doses as the primary treatment for Kawasaki Disease,1, 2 a prototypic vasculitis involving the coronary arteries in children.3 Prevention of coronary artery inflammation, manifested by dilation and or aneurysm formation, is the primary treatment goal. Progression to a giant aneurysm requires anti-coagulation to prevent thrombosis and coronary ischemia.4 Lack of appropriate therapeutic response or refractoriness is defined by a joint statement from the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics as persistent or recurrent fever extending more than 36 hours after completing IVIG infusion.5 Various clinical series report refractory rates between 10 and 30%.6, 7 Refractory patient populations exhibit substantially higher rates of coronary inflammation and aneurysm formation than responsive individuals.7 Although various clinical risk scores have been adopted for use in Japan where KD is endemic,8 their sensitivity in heterogeneous North American populations is poor.9 KD incidence varies considerably according race to and ethnicity. Previous investigators have suggested that the differences in the predictive value of the risk scores also reflect the genetic diversity.9

The IVIG mechanisms of anti-inflammatory action still require elucidation in humans. This knowledge deficit hinders identification of candidate genes involved in KD pathogenesis, and polymorphisms which can predict treatment response. IgG-Fc region receptors (FCγRs) represent plausible KD mediators due to their direct interaction with immunoglobulin G. FcγRs are a heterogeneous group of hematopoietic cell surface glycoproteins that are expressed primarily on human effector cells of the immune system, particularly macrophages, monocytes, myeloid cells and dendritic cells.10 These molecules facilitate antibody-antigen interactions. Studies in mice lacking various forms of FcγR have documented their key roles in the balance between activating and inhibitory receptor signals in experimental idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), as well as for how modulation of this balance might account for the therapeutic effects of IVIG.11 Although the disease processes in mice and humans are not precisely the same, the mechanisms of action of IVIG in these murine models have important connections with their human analogues. The murine models suggest an important and possibly dominant role for the inhibitory FcγRIIB in the IVIG anti-inflammatory mechanism. Genetic association studies in humans support such FcγRIIB participation. However, the low frequency of the particular functional FcγRIIB polymorphisms in all the populations limits its clinically relevant role. 12

The activating Fcγ receptors interact with the single inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB. Thus, we hypothesized that polymorphisms in the activating receptors (FcγRIIA, FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIIB) influence the IVIG treatment response defined by clinical parameters. We also analyzed these receptors with regards to susceptibility, and persistence of coronary artery disease in KD patients. We examined the influence of functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in these genes using a family-based genetic study. We performed the study in a heterogeneous U.S based population of KD patients and their parents containing some ethnic and racial admixture. Substantial FcγR allelic and locus heterogeneity has been demonstrated across different ethnic and racial groups. Therefore, we also performed subgroup analyses in populations of European and Asian descent.

Methods

Study Population

Patients, their parents, and available siblings were identified through clinical databases and enrolled at participating centers - Seattle Children’s Hospital, Oakland Children’s Hospital, and Primary Children’s Hospital of Utah. Retrospective cross-referencing of the hospital database and the Heart Center echocardiography databases confirmed the diagnosis and treatment of all participating KD patients. After approval by the IRB at all participating institutions, parents were approached for study recruitment and informed consent was obtained.

Clinical Diagnosis of KD

The definition of complete KD followed the standard epidemiological criteria recommended by the American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. Patients were also included if they had at least two clinical criteria and coronary artery involvement as defined in the AHA guidelines.5

Treatment Response

Treatment response was determined in patients receiving IVIG (2 gm/kg) within 11 days of initial fever.5 As stated in the AHA/AAP Endorsed Clinical Report,13 failure to respond to IVIG treatment was defined as either persistent fever (temperature > 38° C) at > 36 hours or recurrent fever at > 36 hours after completion of the initial IVIG infusion. Patients receiving second doses of IVIG at < 36 hours were excluded from treatment response analyses unless they had persistent fever despite a second dose of IVIG.

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

CAD was defined by echocardiography as dilation (Z–score>2.5, according to Boston Z-score data14 or aneurysm defined by Japanese Ministry of Health Criteria persisting>6 weeks after IVIG treatment (2 gm/kg).

Bio-specimen Collection and DNA Extraction

Most parents consented to have blood samples taken from their KD offspring, and whole blood was collected in ACD (citrated) anticoagulant tubes. For the remainder saliva was collected in Oragene™ kits (DNA Genotek, Ottawa) by a noninvasive technique proven to preserve DNA. Briefly, participants first rinsed their mouth with water to clear food particles and then expectorated 2 mL of saliva into the Oragene™ vial. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Versagene™ DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and quantified using the PicoGreen assay for double-stranded DNA, adjusted to a final concentration of 100ng/μL, and stored at −80°C in TE.

Activating FcγR genes and polymorphisms

The activating FcγRIIA, FcγRIIIA and FcγRIIIB genes are all located at chromosome position 1q2311, 15 within a span of about 200kb. FcγRIIA has affinity for IgG and interacts with IgG or immune complexed IgG on cell surfaces. FcγRIIIB is a relatively low affinity receptor. FcγRIIIA is expressed as a membrane-spanning receptor on macrophages and natural killer cells. These three genes produce integral transmembrane glycoproteins that are considered functionally activating receptors.

Five well-characterized and functionally relevant SNPs were examined: i) a common FcγRIIA SNP (rs1801274) affecting amino acid position 131 in EC2 region (FcγRIIA-131H/R), A and G alleles at position 131 coding for codominantly expressed arginine (R) and histidine (H), respectively and are known to affect affinity for IgG2 and associated with several immune related diseases;10, 16, 17 ii) a common FcγRIIIA SNP (rs396991), G and T alleles coding either valine (V) or phenylalanine (F), respectively at position 158 in EC2 region (FcγRIIIA-158V/F) known to be associated with immune related diseases,16–18 where valine (V) has higher affinity for IgG1 and IgG3 than the phenylalanine (F) isoform; iii) another triallelic FcγRIIIA SNP (rs10127939) at amino acid position 48 (FcγRIIIA-48L/R/H), T, G and A alleles encoding for either leucine (L), arginine (R) or histidine (H), respectively and are known to influence the binding of IgG by NK cells19; and iv) two FcγRIIIB SNPs at positions 141 (rs403016) and 147 (rs447536) in the extracellular domain 1 (EC1) that result in variable amino acid sequences resulting in two allotypic forms named neutrophil antigen NA1 and NA2. While SNP 141 and SNP 147 are in a perfect-linkage disequilibrium, haplotype is a conventional way to determine NA1 and NA2 allotypes, which has been well-established in the literature.20

Genotyping methods

The functional polymorphisms in the FcγR gene family were genotyped by pyrosequencing methodology using a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) approach to ensure gene-specific amplification.20 Initial gene-specific PCR amplifications of the DNA fragments around the SNP sites were followed by a second round nested PCR reactions using 0.25 ul of the first round PCR products as templates. All PCR reactions were carried out with Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Biotinylated second round PCR products amplified with primer pairs (one of primer pairs is labeled with biotin) were used for subsequent pyrosequencing reactions. The PCR reactions and cycling conditions have been previously described.20, 21 Briefly, amplification is performed with one biotinylated primer to allow for purification of a single stranded template for the pyrosequencing reaction. Following denaturation of the PCR amplicon in 0.1 M NaOH for 10 minutes, the single stranded product is immobilized to streptavidin-sepharose (Amersham Biosciences), washed and annealed with 15 pmoles of a “Pyrosequencing” primer. The primers and probes for the two rounds of PCR and pyrosequencing primers are listed in supplementary Table 1. Pyrosequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described.22

Statistical methods

First, genotype completeness was checked for each SNP and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was examined in each ethnic group. Statistical analysis for KD susceptibility was performed by the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT), which tests for disequilibrium of transmission of alleles from heterozygous parents to affected child and thus applies to parent–child trios. The test statistic for the TDT is distributed as a chi-square with 1 df and is calculated as (b−c)2/(b+c) where b and c are, respectively, the number of transmissions and non-transmissions of the allele from heterozygous parents to their affected children. All analyses were performed assuming additive genetic models with a minimum informative family size set to ten. We used the Family Based Association Test to allow for larger families than trios and incomplete trios with or without siblings. Single-marker FBAT analysis was used to estimate the single locus frequencies.13. A significant p value (<0.05) and a positive Z statistic indicated that the allele at a specific locus is more frequently transmitted to patients with KD than expected under the null hypothesis of no linkage and no association, whereas a significant p value and a negative Z statistic indicated a protective marker allele for KD. For those loci that showed significant differences in FBAT analysis, case/pseudosibling control analysis was performed as previously described.23 The pseudosibling controls were generated from the 3 untransmitted parental genotypes, and conditional logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in the additive model.

As primary analysis of the study, FBAT analyses were performed separately for responders and non-responders to determine if alleles were differentially transmitted. Additionally, as a secondary analysis, differential transmission was examined among CAD and non-CAD patients. All analyses were performed for the entire set of KD patients and also separately for Caucasians and Asians,, as determined by the principal component analysis (PCA) of ancestry informative markers (AIMs), as previously described.12 While FBAT accounts for population admixture, the underlying assumption of the same genetic association may not hold due to allelic and genetic heterogeneity in different ethnic groups. For ethnicity-specific analyses, only families with all members clustered in the same ethnic group (all three for trios and two for the parent-child pair) were included. For quality control, Mendelian inconsistency checks were performed with the AIMs and both parents whose data contained genotyping errors in more than 1 SNP were excluded from the study.

RESULTS

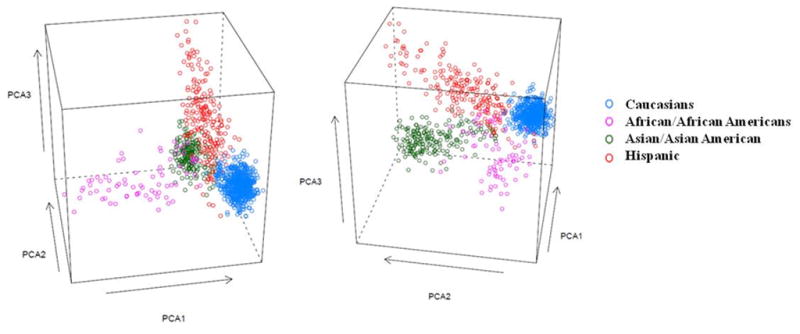

The genotype frequencies for all polymorphisms met Hardy-Weinberg expectations in each population (European and Asian ancestry) and the genotype data was complete for over 95% of the individuals with samples available as the genotype was redone, if they failed in the first attempt. Based on the AIMs, the first three principal component values were used to discriminate individuals into four major race/ethnic groups (Figure 1); one for a homogenous European ancestry, one for a more heterogeneous Asian ancestry, another for a heterogeneous Hispanic ancestry (predominantly Mexican or Mexican-American) and the fourth small one for an African ancestry. However, there were many genetically heterogeneous individuals that could not be defined to one single race/ethnic group. Self-report (or as reported by parents) of all KD patients and participating family members showed slightly less than 90% match with the genetically determined ancestry: 570 out of 599 who self-reported to be Caucasians matched; 153 out of 173 who self-reported to be Asian/Asian American matched; 147 out of 166 who self-reported Hispanic matched; 95 self-reported multiple ethnicity and 61 did not report any ethnicity. Based on the AIMS, we were underpowered with smaller African American sample size and the Hispanic ancestry though distinct from other race/ethnic groups as previously reported24 was very heterogeneous. Therefore, we restricted our analysis in this study to European and Asian ancestry.

Figure 1.

The first, second and third principal components (PC1, PC2 and PC3) based on 155 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) for the entire study population of Kawasaki disease patients and their parents. The clustering of different ethnic groups is shown by different colors; Caucasian (blue), African/African American (pink), Asian/Asian American (green), Hispanic (red).

Other baseline demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age of the probands at diagnosis was 34 months (IQR: 15–58 months) and 62% of them were males, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1, similar to the ratios reported in general populations. The median age between the treatment responders and the non-responders was not significantly different (35 [16–58] vs. 31 [15–66] months), and there were slightly more non-responders (63%) than responders (60%) among males. Of the 443 KD patients recruited into the study (242 Caucasians, 82 Asians, 88 Hispanics and 31 African Americans), 266 trios (156, 44, 52 and 14 from the four ethnic groups, respectively) and 150 single parent-child pair (75, 29, 30 and 16, respectively) were included in the TDT analyses. Seven families were excluded due to Mendelian errors with AIMs. From the review of medical records, 267 patients (141 Caucasians, 57 Asians, 51 Hispanics and 18 of other ethnic groups) could be classified as IVIG treatment responsive and 86 (51 Caucasians, 9 Asians, and 20 Hispanics and 6 of other ethnic groups) patients as non-responsive, with genetic data available for at least one biological parent participating in the study. Interestingly, FcγRIIIA-48 was tri-allelic mostly in Caucasians, but below 5% frequency in other ethnic groups.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participating KD patients

| ALL KD patients* | IVIG Responders | IVIG Non-responders | CAD+ | CAD− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | |||||

| Mean (sd) | 41.9(33.5) | 41.8(32.4) | 41.7(33.2) | 33.5(37.5) | 44.5(32.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 34 (15–58) | 35(16–58) | 31(15–66) | 21(8–50) | 40(19–60) |

|

| |||||

| Race/ethnicity± | |||||

| Caucasian | 242 | 141 | 51 | 42 | 190 |

| Asian | 82 | 57 | 9 | 18 | 59 |

| Hispanic | 88 | 51 | 20 | 21 | 58 |

| African American | 31 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 24 |

|

| |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 263 | 151 | 50 | 59 | 194 |

| Female | 161 | 102 | 29 | 23 | 133 |

89 KD patients either did not have IVIG response data or were in different treatment, 12 did not have CAD data, 30 did not have the age listed and 19 did not have the gender;

race/ethnicity based on Principal component analysis (PCA) and discrimination procedures using 155 Ancestry Informative Markers (AIMS)

Susceptibility

We tested the primary hypothesis relating to IVIG treatment response in patients of European (Caucasian) and Asian ancestry(Asian). However, these polymorphisms influence susceptibility for other inflammatory diseases. Accordingly, we first analyzed their association with disease within the entire study population. Most importantly, we showed excess A allele (histidine) transmission in FcγRIIA-131H/R from heterozygous parents to affected offspring (n = 182, z = +3.12, p = 0.001) in the additive model (Table 2). Ethnic stratification revealed differences in the A allele frequency between Asian and other racial groups. Excess A allele transmission occurred in Caucasians (n = 105, z = +2.04, p = 0.04) and Asian families (n = 26, z = +2.34, p=0.02). Analyses using pseudosibling controls for comparisons with KD patients demonstrated A allele association with KD (ORadditive = 1.51 [1.16–1.96], p = 0.002) for the primary combined study population, for Asians (ORadditive = 2.75 [1.22–6.25], p = 0.01) and for Caucasians (ORadditive = 1.43 [1.02–2.00], p = 0.04) (Table 2). Stratification according to IVIG response (table 2) showed that statistical significance persisted in the combined responders; however, it seemed that the effect was largely observed in Asian responders. Further, using the pseudosibling controls (table 3), the A allele showed increased risk (ORadditive = 1.40 [1.01–1.95], p = 0.04) overall among IVIG responders. Relatively high risk occurred for this allele among Asian responders (ORadditive = 4.00 [1.34–11.96], p=0.01).

Table 2.

TDT and pseudosibling based case-control analysis of polymorphisms in activating FcγR genes with susceptibility to Kawasaki disease in three racial/ethnic groups

| Polymorphisms/Genes Ethnicity | Associated allele frequency | Informative families* | z-statistics (p-value) | OR (95% CI)† | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FcγRIIA-131H/R(a/g) | (A) | ||||

| All Ethnic groups | 0.57 | 182 | +3.12 (0.001) | 1.51 (1.16–1.96) | 0.002 |

| Caucasians | 0.54 | 105 | +2.04 (0.04) | 1.43 (1.02–2.01) | 0.04 |

| Asians | 0.73 | 26 | +2.34(0.02) | 2.75 (1.22–6.18) | 0.01 |

|

| |||||

| FcγRIIIA-48L/R/H(t/g/a) | (G/T) | ||||

| All Ethnic groups | G = 0.04 | 21/35/48 | −0.85 (0.40)/+1.00 (0.32)/−0.27 (0.79) | - | - |

| T = 0.07 | |||||

| Caucasians | G = 0.06 | 17/29/38 | −0.47 (0.64)/+1.10 (0.27)/−0.60 (0.55) | - | |

| T = 0.09 | |||||

| Asians | G = .007 | - | - | - | - |

| T = 0.02 | - | ||||

|

| |||||

| FcγRIIIA-158V/F(t/g) | (G) | ||||

| All Ethnic groups | 0.35 | 179 | +0.46 (0.64) | 1.07 (0.83–1.39) | 0.59 |

| Caucasians | 0.37 | 111 | +0.25 (0.80) | 1.04 (0.75–1.46) | 0.80 |

| Asians | 0.32 | 29 | −2.00 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.27–1.10) | 0.09 |

|

| |||||

| FcγRIIIB-NA/NA2 | (NA1) | ||||

| All Ethnic groups | 0.60 | 157 | +1.88 (0.06) | 1.28 (0.97–1.69) | 0.07 |

| Caucasians | 0.66 | 85 | +1.60 (0.11) | 1.32 (0.90–1.93) | 0.15 |

| Asians | 0.47 | 30 | +1.37 (0.17) | 1.62 (0.81–3.23) | 0.17 |

TDT statistics was only performed where there were 10 or more informative families;

OR (additive) based on the genotype of the KD patients and pseudosibling controls derived from the 3 alternate genotypes based on the untransmitted alleles

Table 3.

TDT and pseudosibling based case-control analysis of activating FcγR gene variants among IVIG responding and IVIG non-responding Kawasaki patients in three racial/ethnic groups†

| Genes & Polymorphisms | IVIG Responders

|

IVIG non-responders

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDT statistics

|

Pseudosibling case-control†

|

TDT statistics

|

Pseudosibling case-control†

|

|||||

| Informative families* | z-statistics (p-value) | OR (95% CI) | p | Informative families* | z-statistics (p-value) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| FcγRIIA-131H/R | ||||||||

| All | 115 | +2.1 (0.04) | 1.40 (1.01–1.95) | 0.04 | 41 | +1.81 (0.07) | 1.72 (0.96–3.08) | 0.07 |

| Caucasians | 67 | +0.97 (0.33) | 1.24 (0.81–1.90) | 0.33 | 21 | +0.76 (0.45) | 1.33 (0.63–2.82) | 0.45 |

| Asians | 17 | +2.40 (0.02) | 4.00 (1.34–11.96) | 0.01 | - | - | 4.00 (0.45–35.79) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||||||

| FcγRIIIA-158V/F | ||||||||

| All | 108 | −0.25 (0.80) | 1.00 (0.72–1.39) | 1 | 40 | +1.48 (0.14) | 1.5 (0.83–2.72) | 0.18 |

| Caucasians | 67 | +0.43 (0.67) | 1.10 (0.72–1.68) | 0.67 | 22 | +0.82 (0.41) | 1.4 (0.62–3.15) | 0.42 |

| Asians | 19 | −2.04 (0.04) | 4.00 (1.34–11.96) | 0.01 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||

| FcγRIIIB-NA1 | ||||||||

| All | 95 | +1.51 (0.13) | 1.28 (0.89–1.82) | 0.18 | 34 | +3.70 (0.0002) | 3.67 (1.75–7.66) | 0.0006 |

| Caucasians | 48 | +1.21 (0.23) | 1.29 (0.79–2.10) | 0.32 | 20 | +2.71 (0.007) | 3.6 (1.34–9.70) | 0.01 |

| Asians | 22 | +0.82 (0.41) | 2.14 (0.87–5.26) | 0.10 | - | - | - | - |

TDT statistics was only performed where there were 10 or more informative families;

OR (additive) based on the genotype of the KD patients and pseudosibling controls derived from the 3 alternate genotypes based on the untransmitted alleles

The FcγRIIIA-158 G allele was transmitted less in Asians (n = 29, z = −2.00, p = 0.05, Table 2), including mostly IVIG responders (n = 19, z = −2.04, p = 0.04, Table 3). However, FCGRIIIA-48L/R/H occurring at low frequency showed no effects. Similarly, FcγRIIIB-NA1 showed no significant association with KD susceptibility (n = 157, z = +1.88, p = 0.06, table 2).

IVIG Non-response

We found FcγRIIIB-NA1 excessive transmission in the IVIG non-responding subgroup (n = 34, z = +3.70, p = 0.0002, table 3). This highly significant effect was detected in Caucasians (n = 20, z = +2.71, p = 0.007, Table 3) on subgroup analysis; we lacked adequate numbers of informative families to test transmission in the Asians. Pseudosibling analyses revealed the corresponding odds ratios for the combined and Caucasian IVIG non-responders (ORadditive = 3.67 [1.75–7.66], p = 0.0006 and 3.60 [1.34–9.70], p = 0.01), respectively (Table 3). No such over-transmission was observed among IVIG responding patients, suggesting that any marginal effect detected in the combined study population, could be due to the non-responders.

Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

As noted, prevention or resolution of CAD is the principal goal of KD therapy. Thus, we defined CAD persistence a priori as an important clinical parameter, also related to IVIG response. We identified 86 patients with persistent CAD (42 Caucasians and18 Asians and 26 of other ethnic groups), 331 with no CAD and 26 with a missing diagnosis. Excess transmission of the A in FcγRIIA-131H/R occurred in CAD patients (Tables 4), but was not apparent in Caucasians or Asians separately. However, this occurred in concert with excess transmission for the entire KD population. In contrast, FcγRIIIB- NA1 excess transmission occurred in CAD patients, consistent with findings in the IVIG non-responders, but despite lack of apparent effect on the entire combined KD patients.

Table 4.

Results of TDT and pseudosibling based case-control analysis of polymorphisms in activating FcγR genes among Kawasaki disease patients with and without coronary artery disease (CAD) in three racial/ethnic groups†

| Genes & Polymorphisms | KD patients without CAD (n = 331)

|

KD patients with CAD (n = 86)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDT statistics

|

Pseudosibling case-control†

|

TDT statistics

|

Pseudosibling case-control†

|

|||||

| Informative families* | z-statistics (p-value) | OR (95% CI) | p | Informative families* | z-statistics (p-value) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| FcγRIIA-131H/R | ||||||||

| All | 127 | +1.79 (0.07) | 1.33 (1.02–1.82) | 0.07 | 43 | +2.45 (0.01) | 1.89 (1.10–3.33) | 0.03 |

| Caucasians | 79 | +2.05 (0.04) | 1.52 (1.01–2.22) | 0.04 | 20 | 0 (1) | 1.00 (0.46–2.16) | 1 |

| Asians | 17 | +1.15 (0.25) | 0.58 (0.23–1.48) | 0.26 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||

| FcγRIIIA-158V/F | ||||||||

| All | 134 | −0.23 (0.82) | 0.96 (0.71–1.31) | 0.81 | 40 | +1.66 (0.10) | 1.57 (0.88–2.80) | 0.13 |

| Caucasians | 91 | 0 (1) | 1.00 (0.69–1.55) | 1 | 18 | +0.85 (0.39) | 1.44 (0.62–3.38) | 0.40 |

| Asians | 21 | −1.63 (0.10) | 0.50 (0.21–1.17) | 0.11 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||||

| FcγRIIIB-NA1 | ||||||||

| All | 113 | +0.65 (0.52) | 1.09 (0.80–1.49) | 0.58 | 35 | +2.41 (0.02) | 2.13 (1.11–4.00) | 0.02 |

| Caucasians | 63 | +1.07 (0.29) | 1.24 (0.81–1.85) | 0.28 | 17 | +1.34 (0.18) | 1.85 (0.70–4.76) | 0.19 |

| Asians | 21 | +0.82 (0.41) | 1.41 (0.62–3.15) | 0.42 | - | - | - | - |

TDT statistics was only performed where there were 10 or more informative families (several SNPs, specifically FcγRIIIA-48R/L did not have enough informative families especially in Asians and Hispanics);

OR (additive) based on the genotype of the KD patients and pseudosibling controls derived from the 3 alternate genotypes based on the untransmitted alleles

DISCUSSION

The principal finding in our hypothesis driven study, a highly significant association between IVIG response and FcγRIIIB genotype in KD patients, has important pharmacogenomic and clinical implications. Reinforcing demonstration that parental transmission of NA1 genotype substantially decreases the odds of appropriate clinical IVIG response, our study also showed that this genotype confers substantially greater risk of persistent coronary artery disease. No prior investigation has specifically evaluated the impact of polymorphisms for genes transcribing FCγ activating receptors on clinically defined IVIG response. However, few studies analyzed associations between FCγRs including NA1/NA2 and coronary artery lesions.25, 26 Though they did not define coronary artery phenotype, only Biezeveld et al25 reported slightly decreased risk (OR = 0.42 [0.16–1.06]; p = 0.06) of coronary artery lesions in Caucasian KD patients with the genotype NA1/NA2 compared to NA1/NA1. Likely, our greater number of informative patients combined with parent data, with genetically determined homogenous populations, within the TDT and FBAT framework provided adequate power to detect these NA1 associations with clearly defined phenotypes.

The potential biological mechanisms responsible for different IVIG responses between the NA1 and NA2 isoforms require elucidation. FcγRIIIB is expressed almost exclusively on neutrophils, although recent data show low level expression in human basophils.27 NA1 confers greater neutrophil IgG dependent phagocytic capacity than NA2.10 This may relate to differences in the number of functionally relevant N-linked glycosylation sites that affect their interaction with IgG as NA1 has a higher binding affinity for IgG1 and IgG3. Alternatively, NA1 and NA2 may interact differently with other cell surface receptors such as β2 integrin, CD11b/CD18. Some clinical and pathological evidence suggests an important role for neutrophils in KD and coronary artery pathogenesis.28 In particular, CD11b expression on neutrophils rises during the acute disease phase, declines after treatment, and remains elevated in with persistent coronary artery disease.29 Our data offer an intriguing possibility that IVIG manipulates NA1/NA2 dependent activity in KD.

We also found excess transmission of the more potent FcγRIIA-131H variant among KD patients. This finding validates a recent report from a genome-wide association study by an international KD consortium.30 The polymorphism (A/g) in FcγRIIA-131H/R alters recognition of ligand in that the receptor encoded by FcγRIIA-131H shows greater binding affinity for IgG2,31 and thus more effective phagocytosis of IgG2 opsonized particles. This receptor variant also shows decreased binding affinity for C-reactive protein, which shares several functional activities with IgG2 and is markedly elevated during acute KD. Tanuichi et al previously reported an FcγRIIA-131H association with CAD in a small set of Japanese KD patients.26 However, our data suggest that this allele relates to overall KD susceptibility rather than specific coronary artery disease risk.

The multiple FcγR activating receptors interact with FcγRIIB (inhibitory) and/or each other through their co-ligation at the immune effector cell membrane. Thus, functional polymorphisms within the genes regulating these receptors can alter the balance between activation and inhibition and thereby influence their interaction. Strengths of associations between individual FcγR SNPs and inflammatory disease susceptibility clearly vary by race and may be explained by the racial variation in the gene sequences of the other receptors. As previously noted, FcγRIIB polymorphisms influence IVIG response in KD patients in a racially dependent manner. The presence of FcγRIIB (−120 A and −386 C) minor alleles in Caucasian patients improved their chance for positive IVIG therapeutic response.12 Functionality for these SNPs within the human FcγRIIB promoter region has been confirmed in that they enhance transcription factor binding. Yet, these SNPs were absent in the Asians studied, further emphasizing that balance between the activating and inhibitory receptors varies by ethnicity. While these FcγR genes are located in the same region, with high linkage disequilibrium (D′), the SNPs were not highly correlated. The correlations (r2), however also varied between the two ethnic groups.

In following, we logically performed ethnicity specific analyses for the FcγRs in the current study. There are limitations related to the ethnic stratification. The low number of informative families for the SNPs within these subgroups limited the power of our observations. Correction for multiple testing is conventionally performed for non-candidate based studies such as GWAS, which evaluate numerous variants. Some might suggest that our stratification introduces the requirement for such correction. However, the need for correction in a hypothesis driven study, evaluating functional SNPs, remains controversial. With regard to our observed associations related to the ethnic stratification as well as coronary artery disease, significance is somewhat less. We cautiously report these latter findings, which will require validation with larger subject numbers in these ethnic groups.

Supplementary Material

Kawasaki Disease is a prototypic vasculitis in children and is diagnosed by presence of fever, clinical features, and supportive laboratory criteria. The vasculitis shows a predilection for the coronary arteries. Coronary artery inflammation can result in dilation and or aneurysm formation. Intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG) infusion with aspirin successfully treats fever and prevents coronary artery inflammation. The mechanism of IVIG action has not been substantiated. Many patients demonstrate refractoriness to IVIG treatment with persistent or recurrent fever, and remain at high risk for development of coronary artery disease. Prior studies have suggested that IgG-Fc region receptors (FCγRs) represent plausible KD mediators due to their direct interaction with immunoglobulin G. In the current study we demonstrate that polymorphisms for genes regulating the activating FCγRs are associated both with IVIG treatment response and susceptibility to KD. In particular, family based testing shows that the FCγRIIIB-NA1 haplotype is excessively transmitted to non-IVIG responding patients in our KD population. Confirmation of this association in an independent KD population would further substantiate genotyping for this polymorphism as a mode of predicting IVIG response. Thus, the genotype could be used early in the disease to determine whether alternative forms of treatment would be beneficial. Additionally, we offer confirmation for other studies that FCγRIIA-131H polymorphism relates to disease susceptibility. This genotype could be pursued as a tool for diagnosis and evaluation of KD pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This data was presented in part at the Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association, Orlando, November 14, 2011. We are grateful to participating patients and their parents as well as the investigators, pediatricians and staffs of the participating clinics. We thank Dolena Ledee for handling of the biospecimens and DNA extraction and Deborah S McDuffie for genotyping.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by grants NHLBI-R21-HL90558 & Thrasher Foundation Research Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Furusho K, Kamiya T, Nakano H, Kiyosawa N, Shinomiya K, Hayashidera T, et al. High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1984;2:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Beiser AS, Burns JC, Bastian J, Chung KJ, et al. A single intravenous infusion of gamma globulin as compared with four infusions in the treatment of acute kawasaki syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1633–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawasaki T. [acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children] Arerugi. 1967;16:178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns JC, Glode MP. Kawasaki syndrome. Lancet. 2004;364:533–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of kawasaki disease: A statement for health professionals from the committee on rheumatic fever, endocarditis, and kawasaki disease, council on cardiovascular disease in the young, american heart association. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1708–1733. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns JC, Capparelli EV, Brown JA, Newburger JW, Glode MP. Intravenous gamma-globulin treatment and retreatment in kawasaki disease. Us/canadian kawasaki syndrome study group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:1144–1148. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace CA, French JW, Kahn SJ, Sherry DD. Initial intravenous gammaglobulin treatment failure in kawasaki disease. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E78. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi T, Inoue Y, Otani T, Morikawa A, Takeuchi K, Saji T, et al. Risk stratification in the decision to include prednisolone with intravenous immunoglobulin in primary therapy of kawasaki disease. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2009;28:498–502. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e3181950b64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sleeper LA, Minich LL, McCrindle BM, Li JS, Mason W, Colan SD, et al. Evaluation of kawasaki disease risk-scoring systems for intravenous immunoglobulin resistance. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;158:831–835. e833. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Pol W, van de Winkel JG. Igg receptor polymorphisms: Risk factors for disease. Immunogenetics. 1998;48:222–232. doi: 10.1007/s002510050426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. Igg fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrestha S, Wiener HW, Olson AK, Edberg JC, Bowles NE, Patel H, et al. Functional fcgr2b gene variants influence intravenous immunoglobulin response in patients with kawasaki disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:677–680. e671. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns JC, Shimizu C, Gonzalez E, Kulkarni H, Patel S, Shike H, et al. Genetic variations in the receptor-ligand pair ccr5 and ccl3l1 are important determinants of susceptibility to kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:344–349. doi: 10.1086/430953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrindle BW, Li JS, Minich LL, Colan SD, Atz AM, Takahashi M, et al. Coronary artery involvement in children with kawasaki disease: Risk factors from analysis of serial normalized measurements. Circulation. 2007;116:174–179. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maresco DL, Chang E, Theil KS, Francke U, Anderson CL. The three genes of the human fcgr1 gene family encoding fc gamma ri flank the centromere of chromosome 1 at 1p12 and 1q21. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;73:157–163. doi: 10.1159/000134330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brun JG, Madland TM, Vedeler CA. Immunoglobulin g fc-receptor (fcgammar) iia, iiia, and iiib polymorphisms related to disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binstadt BA, Geha RS, Bonilla FA. Igg fc receptor polymorphisms in human disease: Implications for intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:697–703. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bournazos S, Woof JM, Hart SP, Dransfield I. Functional and clinical consequences of fc receptor polymorphic and copy number variants. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Haas M, Koene HR, Kleijer M, de Vries E, Simsek S, van Tol MJ, et al. A triallelic fc gamma receptor type iiia polymorphism influences the binding of human igg by nk cell fc gamma riiia. J Immunol. 1996;156:3948–3955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edberg JC, Langefeld CD, Wu J, Moser KL, Kaufman KM, Kelly J, et al. Genetic linkage and association of fcgamma receptor iiia (cd16a) on chromosome 1q23 with human systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2132–2140. doi: 10.1002/art.10438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su K, Li X, Edberg JC, Wu J, Ferguson P, Kimberly RP. A promoter haplotype of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-bearing fcgammariib alters receptor expression and associates with autoimmunity. Ii. Differential binding of gata4 and yin-yang1 transcription factors and correlated receptor expression and function. J Immunol. 2004;172:7192–7199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edberg JC, Wu J, Langefeld CD, Brown EE, Marion MC, McGwin G, Jr, et al. Genetic variation in the crp promoter: Association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1147–1155. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordell HJ, Barratt BJ, Clayton DG. Case/pseudocontrol analysis in genetic association studies: A unified framework for detection of genotype and haplotype associations, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions, and parent-of-origin effects. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:167–185. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva-Zolezzi I, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Estrada-Gil J, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Uribe-Figueroa L, Contreras A, et al. Analysis of genomic diversity in mexican mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8611–8616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biezeveld M, Geissler J, Merkus M, Kuipers IM, Ottenkamp J, Kuijpers T. The involvement of fc gamma receptor gene polymorphisms in kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taniuchi S, Masuda M, Teraguchi M, Ikemoto Y, Komiyama Y, Takahashi H, et al. Polymorphism of fcgamma riia may affect the efficacy of gamma-globulin therapy in kawasaki disease. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-4697-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meknache N, Jonsson F, Laurent J, Guinnepain MT, Daeron M. Human basophils express the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored low-affinity igg receptor fcgammariiib (cd16b) J Immunol. 2009;182:2542–2550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biezeveld MH, van Mierlo G, Lutter R, Kuipers IM, Dekker T, Hack CE, et al. Sustained activation of neutrophils in the course of kawasaki disease: An association with matrix metalloproteinases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141:183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi T, Kimura H, Okada Y, Inoue Y, Shinohara M, Morikawa A. Increased cd11b expression on polymorphonuclear leucocytes and cytokine profiles in patients with kawasaki disease. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2007;148:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khor CC, Davila S, Breunis WB, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Wright VJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies fcgr2a as a susceptibility locus for kawasaki disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1241–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warmerdam PA, van de Winkel JG, Vlug A, Westerdaal NA, Capel PJ. A single amino acid in the second ig-like domain of the human fc gamma reeptor ii is critical for human igg2 binding. J Immunol. 1991;147:1338–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.