Abstract

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of calciuria as a diagnostic test for the prediction of preeclampsia, and also to determine the changes in urinary excretion of calcium in preeclampsia and normotensive women.

Methods

A prospective study was conducted on 60 primi mothers in the age group of 20–30 years, and all were enrolled at 16 weeks of gestation with clinical follow up by 4 weeks and 24 h urinary calcium and creatinine estimation. Ten mothers developed preeclampsia (study groups) and fifty remained normotensive (control groups). By means of Receiver-operator curve, a cut-off level of urinary calcium in 24 h was chosen for predicting preeclampsia.

Results

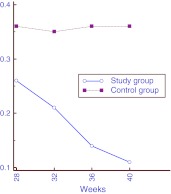

Preeclamptic women excreted significantly less total urine calcium (87.0 ± 3.59 mg/24 h) than normotensive women (303.68 ± 17.699 mg/24 h) (p < 0.0001) at 40 weeks of gestation. Urinary calcium and calcium/creatinine (Ca:Cr) ratio decreases progressively from 28 weeks to 40 weeks in the study group when compared to normotensive group.

Conclusions

Preeclamptic women excrete less calcium than normotensive women. This parameter would predict preeclampsia earlier in pregnancy.

Keywords: Preeclampsia, Calcium, Hypocalciuria, Urinary calcium/creatinine ratio

Introduction

Hypertensive disorder complicates pregnancy and form one aspect of the deadly triad along with haemorrhage and infection and result in significant maternal morbidity and mortality [1].

The exact aetiology of hypertensive disorder is still unknown and management is controversial. The predominant pathology is endothelial dysfunction which sets in early 8–18th weeks of gestation, but the signs and symptoms appear in late mid trimester or in the advanced stage of the disease [2]. Calcium homeostasis is altered in women with preeclampsia. In its clinical phase, preeclampsia is a hypocalciuric state and it has been reported that hypocalciuria predicts preeclampsia [3]. In order to arrest the disease process in the initial phase or to prevent later complications, various predictors are now at hand.

With the approval of ethics committee, this prospective study was carried out to assess the value of 24 h urinary calcium measurement in predicting preeclampsia and also to evaluate renal calcium excretion in women with preeclampsia and compared with normotensives.

Materials and Methods

Sixty primigravida women who were in the age group of 20–30 years and <20 weeks gestation were enlisted to perform the prospective study (from July 2009 to June 2010) attending the antenatal clinic of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Burdwan Medical College, Burdwan. The pregnant mothers were enrolled at 16 weeks of gestation by random sampling by a table of random number method and followed up until delivery. Women with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, anaemia (haemoglobin <8 gm%), multiple gestations or urinary tract infections were excluded from the study. Informed consent was taken for all women.

Routine investigations along with the measurement of blood pressure, weight, 24 h urinary protein, calcium and creatinine were performed at the time of registration and then at 4 weeks interval till EDD/onset of labour. Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia were clinically evaluated at each follow up visit. Preeclampsia has been defined as BP of ≥140 mm of Hg systolic (Korotkoff’s I sound) and ≥90 mm of Hg (Krotkoff’s V sound) taken twice 6 h apart after 20 weeks of gestation with a total protein excretion of greater than 300 mg in 24 h in previously normotensive and nonproteinuric woman. The woman was asked to come with 24 h urine from 6 a.m. to next day 6 a.m. in a container. The collection was between the second morning specimen of the first day and the first morning fasting urine of the second day.

Calcium level of urine sample was analysed by the colorimetric method using the semi analyser and was estimated by the OCPC method at 575 nm. The formula for calcium estimation is calcium concentration (mg/dl) =

|

Creatinine level has also been estimated by the alkaline picrate method by Jaffe reaction on at 520 nm.

The formula for creatinine estimation =

|

where AS is the absorbance of the sample and ASt is the absorbance of the standard.

Urinary protein has been measured by a commercially available dipstick. Proteinuria ≥1 + (300 mg/24 h) have been considered significant.

Normal data were expressed as percentage, and comparison of all outcomes among the study and control groups were done by unpaired student ‘t’ test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean; standard deviation and ‘p’ value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The receiver-operator curve (ROC) analysis technique was used to determine the best cut-off level for the prediction of preeclampsia and the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were also calculated according to the cut-off value by means of a statistical package.

Results

Of the 60 pregnant mothers included in the study, 10 (16.66 %) developed preeclampsia and were considered as the study group, and the rest 50 (83.34 %) normotensive women were considered as the control group. Ninety percent of preeclamptic mothers were in the age groups of 20–25 years (mean ± SD, 22.62 ± 2.50 years). Maximum preeclamptic mothers (50 %) belonged to lower middle socio-economic groups, 30 % belonged to middle class and 20 % came from lower economic groups. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the patients. Mean age did not differ significantly in the two groups. Pregnant mothers with preeclampsia delivered at an earlier gestational age (p < 0.0001). As a result, the mean birth weight was significantly lower in the preeclamptic groups (p < 0.0001). The systolic and diastolic BP at 40 weeks in preeclamptic women was higher than in the controls (p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Patient’s characteristics of the study and control groups

| Pre-eclamptic (n = 10) | Normotensives (n = 50) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Study group) | (Control group) | ||

| Age (years) | 22.6 ± 2.50 | 21.9 ± 1.91 | 0.3196 |

| GA (weeks) at delivery | 35.7 ± 1.34 | 39.76 ± 1.079 | < 0.0001* |

| Birth weight of baby | 2390 ± 166 | 3,423 ± 69 | <0.0001* |

| BP (mm of Hg) | |||

| 20 weeks (Systolic) | 113.60 ± 4.35 | 110.76 ± 4.35 | 0.0645 |

| (Diastolic) | 71.60 ± 1.36 | 71.68 ± 4.70 | 0.9579 |

| 40 weeks (Systolic) | 156.8 ± 4.34 | 134.00 ± 2.02 | <0.0001* |

| (Diastolic) | 102 ± 4.89 | 86.74 ± 3.28 | <0.0001* |

| Family H/O PIH | 3 (30) | 6 (12) | |

| Edema | 10 (100) | 8 (16) | |

| Proteinuria | 10 (100) | nil | |

| Retinal changes | 3 (30) | nil | |

Mean ± SD, BP, blood pressure, n (%)

* p values highly significant

Table 2 lists the urine and serum laboratory findings. Patients with preeclampsia had significantly lower excretion of calcium at 40 weeks. Likewise, the creatinine clearance was also lower in women with preeclampsia than in normotensive women at the gestational age of 40 weeks. This difference, however, was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). Excretions of urinary protein and serum uric acid were increased in preeclampsia.

Table 2.

Laboratory data of different groups

| Study group (n = 10) | Control group (n = 50) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dl) | |||

| 20 weeks | 11.51 ± 0.414 | 11.49 ± 0.403 | 0.8871 |

| 40 weeks | 10.43 ± 0.333 | 10.53 ± 0.487 | 0.5384 |

| Serum uric acid level (mg/dl) | |||

| 20 weeks | 3.317 ± 0.072 | 3.386 ± 0.152 | 0.1677 |

| 40 weeks | 4.84 ± 0.458 | 3.878 ± 0.089 | <0.0001* |

| 24 h urinary creatinine (mg/24 h) | |||

| 20 weeks | 837.1 ± 4.175 | 803.74 ± 48.231 | 0.0340 |

| 40 weeks | 785.4 ± 8.208 | 846.04 ± 43.970 | 0.0001 |

| 24 h urinary protein (mg/24 h) | |||

| 20 weeks | 269.600 ± 2.875 | 248.44 ± 16.612 | 0.0002 |

| 40 weeks | 431.300 ± 24.004 | 283.08 ± 19.397 | <0.0001* |

| 24 h calcium excretion (mg/24 h) | |||

| 40 weeks | 87.000 ± 3.590 | 303.68 ± 17.699 | <0.0001* |

BP blood pressure

Mean ± SD, n (%)

* Highly significant

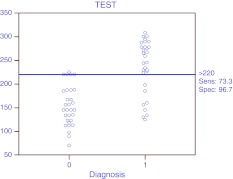

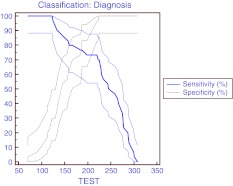

Table 3 contains the criterion value and coordinates of receiver-operator curve (ROC) of 24 h urinary calcium excretion at 16 weeks of gestation and the best cut-off value for calcium by Youden’s index is >220 mg with J = 0.70. At the cut-off point of >220 mg, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value sequentially are 73, 97, 96 and 78 %, respectively, for the prediction of preeclampsia.

Table 3.

Criterion value and coordinates of ROC curve of 24 h urinary calcium excretion at 16 weeks of gestation

| Criterion 24 h urinary excretion of ‘Ca’ | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | +LR (%) | −LR (%) | +PV (%) | −PV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥70 mg | 100.00 | 0.0 | 1.00 | − | 50.00 | − |

| (88.4–100.00) | (0.0–11.6) | (36.8–63.2) | ||||

| >188 | 76.67 | 83.33 | 4.60 | 0.28 | 82.1 | 78.1 |

| (57.7–90.1) | (65.3–94.4) | (3.6–5.9) | (0.1–0.8) | (62.7–94.1) | (59.7–90.9) | |

| >220 mg* | 73.33 | 96.67 | 22.00 | 0.28 | 95.7 | 78.4 |

| (54.1–87.7) | (82.8–99.9) | (17.6–27.6) | (0.04–2.1) | (77.4–99.9) | (61.8–90.2) | |

| >308 mg | 0.0 | 100.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 50.0 |

| (0.0–11.6) | (88.4–100.0) | (36.8–63.2) |

+LR positive likelihood ratio, −LR negative likelihood ratio, +PV positive predictive value, −PV negative predictive value

Data presented as mean (95 % confidence interval)

* You den’s index (J) = sensitivity + specificity – 1 (=0.73 + 0.97 − 1) = 0.70 (The maximum value ‘J’ can attain is 1 when the test is perfect, and the maximum value is usually 0 when the test has no diagnostic value)

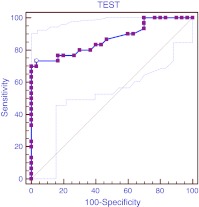

Table 4 includes the results of test of the area under the ROC curve (AUROC), which is 0.869 (>0.5) and signifies whether using calcium in 24 h urine to diagnose preeclampsia is better than to chance alone. The p value is <0.0001 and the confidence interval for AUROC is 0.757–0.943, suggesting that the calcium level in 24 h urine does help to predict preeclampsia.

Table 4.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for calcium excretion of 24 h of urine

| AUROC* | Standard error | Significance level p (area = 0.5) | 95 % confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| 0.869 | 0.0476 | <0.0001 | 0.757a | 0.943 |

aBinomial exact; Z value 7.760

* The ideal test would have an AUROC of 1, whereas a random guess would have an AUROC of 0.5

Figure 1 shows the interactive dot diagram of the criterion value of ROC curve.

Fig. 1.

Interactive dot diagram; X-axis plotted the diagnosis (0, 1) and Y-axis, calcium level in mg/24 h urine

Figure 2 shows the ROC curve (a graph of sensitivity against 100-specificity) for calcium in 24 h urine which starts at the origin (0, 0), goes vertically up the y-axis to (0,100) and then horizontally across to (100,100). A good test would be somewhere close to this ideal. The performance of a diagnostic variable can be quantified by calculating the area under the ROC curve (AUROC).

Fig. 2.

Receiver-operator characteristic curve (ROC) for urinary calcium excretion in 24 h data at 16 weeks of gestation obtained by a statistical package. The dashed line is the diagonal line (0, 0) to (100,100). ‘o’ marks the point with highest accuracy in the curve

Figure 3 shows the mean value of 24 h urinary calcium level at 28 weeks; it was 207 ± 4.371 mg (range, 202–216 mg) in the study group and 301.4 ± 15.335 mg (range, 276–330 mg) in the control group. At 40 weeks of gestation or at the time of delivery, the 24 h urinary calcium was 87.00 ± 3.59 mg (range, 82–93 mg) in the study group and 303.68 ± 17.699 mg (range, 270–330 mg) in the control group.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between the mean urinary calcium levels in 24 h with gestational age of pregnancy. Y-axis urinary calcium in mg per 24 h, X-axis gestational age in weeks

Figure 4 shows the curves of urinary Ca: Cr ratio in two groups. In the study group, the ratio was 0.26 at 28 weeks of gestation and 0.11 at 40 weeks of gestation. In the control group, at 28 weeks and 40 weeks of gestation the ratio was 0.36 and 0.36, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between calcium and creatinine (Ca:Cr) ratio in 24 h urine sample(Y, mg/24 h) and gestational age (X, weeks) in both the groups

The plot versus criterion value with 95 % confidence interval as a connected line is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Plot versus criterion value (95 % confidence interval as connected line)

Discussion

Incidence of preeclampsia was 16.6 % in our study. Suarez et al. [3] indicated a higher incidence (21.7 %) and this was probably due to the selection of the primigravidas who were young. The patient with preeclampsia in our study delivered at an earlier gestation. As a result of this, birth weights were significantly lower (p < 0.0001).Vaginal delivery occurred in 70 % of our study cases. In this study, it was found that significant hypocalciuria was associated with preeclampsia, suggesting that calcium measurement may be useful in screening for the condition.

Renal excretion of calcium increases during normal pregnancy, and hypercalciuria in normal pregnancy is a consequence of an increased glomerular filtration rate [4]. The normal 24 h urinary excretion of calcium was 300 mg. Taufield et al. [5] noted marked hypocaciuria with hypertensive disorder in pregnancy. Sanchez- Ramos et al. [4] reported that excretion of calcium was reduced in the third trimester in preeclampsia and total urinary calcium excretion (129.7 mg/24 h) was significantly lower than that observed for normotensive patients (293.9 mh/24 h). Bilgin et al. [6] also showed preeclamptic women excreted significantly less total urine calcium (150.1 ± 21.41 mg/24 h) than normotensive women (296.0 ± 14.4 mg/24 h) (p < 0,001). Ramos et al. [7] found that a 24 h calciuria <100 mg/24 h may confirm a suspected case preeclampsia. In our study group, every patient had calcium level below 100 mg/24 h urine at 40 weeks or at the time of delivery which was earlier. The pathogenesis of hypocalciuria in preeclampsia is controversial and theoretically it may be due to decreased intestinal absorption, increased calcium uptake by the foetus or increased renal tubular reabsorption of calcium [8]. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) was lower in preeclampsia due to increased renal calcium absorption, thereby reaching a new steady state of normocalcemia associated with lower PTH [9]. Pedersen et al. [10] reported that the fractional excretion of calcium was reduced in the third trimester in preeclamptics as compared with normotensives. Because parathyroid hormones and calcitonin levels were not altered in the patients with preeclampsia, they concluded that the difference in calcium metabolism was not noted to alter the secretion of these hormones. Urinary calcium excretion is a very good tool for the prediction of preeclampsia as it is easy to carry out, non-invasive and not much expensive. The diurnal variation of calcium or (creatinine) excretion with a peak at or before mid day makes 24 h values preferable. The use of other 24 h studies like urinary calcium/creatinine ratio, protein as early predictors will help to identify pregnant female at high risk of preeclampsia [11] and prompt the initiation of education and prophylactic intervention (i.e., primary prevention, e.g., close prenatal care, high dose calcium supplementation, low dose aspirin/or nitric oxide donors) [3]. These tests can also be used as a selection criterion in research studies.

Conclusion

Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder of complex origin and prevention of it is not yet possible. So, prediction of preeclampsia in early weeks of pregnancy may reduce maternal and foetal complications by proper management. Several predictors have been proposed. Hypocalciuria is one such predictor. ROC analysis of calcium in 24 h urine provides useful means to assess the prediction of preeclampsia. The present result showed lower urinary calcium excretion in the group with preeclampsia than normotensive pregnant mothers and a 24 h calciuria less than 100 mg/24 h may confirm a suspected preeclampsia.

References

- 1.Sirohiwal D, Dahiya K, Khaneja N. Use of 24-hour urinary protein and calcium for prediction of preeclampsia. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:113–115. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasgupta M, Adhikary S, Mamtaz S. Urinary calcium in pre-eclampsia. Indian J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;58:308–313. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suarez VR, Trelles JG, Miyahira JM. Urinary calcium in asymptomatic primigravida who later developed preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Ramos L, Sandroni S, Andres FJ. Calcium excretion in preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:510–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taufield PA, Ales KL, Resnick LM, et al. Hypocalciuria in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:715–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703193161204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilgin T, Kultu O, Kimya Y, et al. Urine calcium excretion in preeclampsia. T Kin J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;10:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos JGL, Martins-Costa SH, Kessler JB, et al. Calciuria and preeclampsia. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31:519–522. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1998000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenkel Y, Barkai G, Mashiach S, et al. Hypocalciuria of preeclampsia is independent of parathyroid hormone. J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:689–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart AF, Broadus AE. Mineral metabolism. In: Felig P, Baxter JD, Broadus AE, Frohman WH, editors. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1987. p. 1322. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen EB, Johannesen P, Kristensen S, et al. Calcium, parathyroid hormone and calcitonin in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1984;18:156–164. doi: 10.1159/000299073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguer MH, Masaki DI, Mestman J, et al. Calcium/creatinine ratio and microalbuminuria in the prediction of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:1452–1455. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]