Abstract

Gossypiboma or textiloma is referred to as a surgical gauze or towel inadvertently retained inside the body following surgery. It is an infrequent but avoidable surgical complication, which must be kept in mind in any postoperative patient who presents with pain, infection, or palpable mass. Gossypiboma, in the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur, proves that the surgeon is negligent. Moreover, it has medicolegal consequences including mental agony, humiliation, huge monetary compensation and imprisonment on the part of the surgeon and increased morbidity, mortality and financial loss on the part of the patient. Here we report two cases of gossypiboma and review its current medicolegal aspect in relation to the surgeon.

Keywords: Gossypiboma, Medical negligence, Medicolegal aspect

Introduction

‘Doctor liable for damages where foreign object left in body after surgery—In a case of medical negligence where a gastroenterologist performed explorative laparotomy and left a surgical mop (gossypiboma) in the body that resulted in complications necessitating a second surgery, the National Commission held that this constituted medical negligence. The complainant was awarded `3.5 lakhs as compensation for medical expenditure, mental agony and trauma [1]’.

Gossypiboma [2–5] is a mass lesion due to a retained surgical sponge surrounded by foreign-body reaction. It can cause serious morbidity and even mortality. Because it is not anticipated, it is frequently misdiagnosed, and often unnecessary radical surgical procedures are performed. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any postoperative case with unresolved or unusual problems. Patients develop symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and weight loss, resulting from obstruction or a malabsorption-type syndrome caused by multiple intestinal fistulas or intraluminal bacterial overgrowth. The complications caused by these foreign bodies are well known, but cases are rarely published because of medicolegal implications [6].The diagnosis of gossypiboma and the second remedial surgical operation needed to rectify the medical problem can lead to start of a legal battle between the patient and the surgeon at fault. The medicolegal consequences of gossypiboma are significant. Patients may be inadvertently informed that masses might be malignant and may unnecessarily undergo invasive investigations, procedures, or operations. Gossypiboma may lead to disappointing and undesired consequences for a surgeon. Moreover, it is one of the significant problems that need to be solved by prevention and adequate routine precaution, or else it may lead to litigation and its sequel. We report two cases treated at IPGMER/SSKM Hospital, Kolkata.

Case 1

A 39-year-old male underwent an emergency appendicectomy operation in a government hospital in Mumbai. One month later, the patient came to our hospital with fever, occasional vomiting, pain, distension of abdomen and constipation. The patient was dehydrated and anaemic with tachycardia, hypotension and low urine output. His abdomen was distended with increased bowel sound. There was no rectal ballooning. Blood report showed leucocytosis and decreased haemoglobin level. Radiologically, multiple air fluid levels were present, suggestive of intestinal obstruction. The patient was managed conservatively, but his features of intestinal obstruction did not resolve. On exploratory laparotomy, an intraluminal surgical sponge was found 15 cm proximal to ileocaecal junction (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Involved ileal segment was resected and end to end ileoileal anastomosis was done. His postoperative recovery was uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Surgical sponge at the terminal ileum

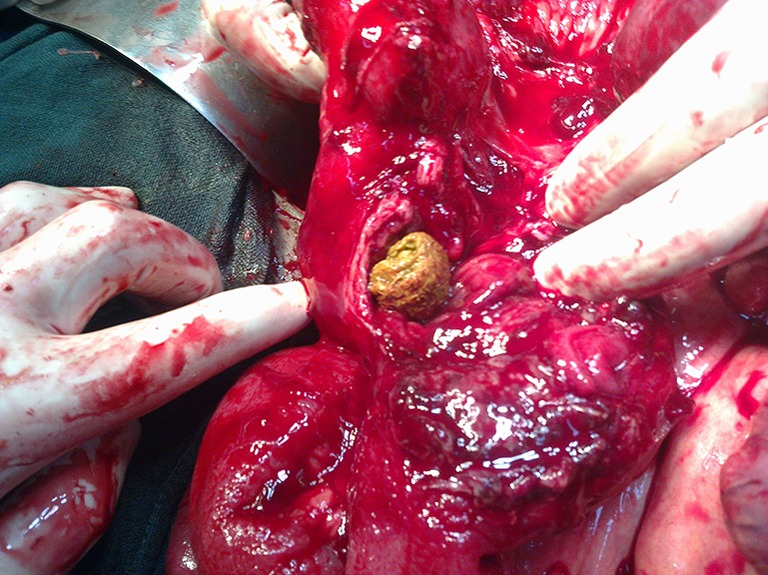

Fig. 2.

Surgical sponge being taken out from the ileum

Fig. 3.

Sponge outside the ileum

Case 2

A 45-year-old female patient underwent open cholecystectomy for gallstone disease at a private nursing home. Seven days following the operation, the patient complained of pain abdomen, vomiting and fever associated with chills and rigor. On examination, increased temperature, tachycardia and hypotension were found. The abdomen was distended with guarding and rigidity. There was a palpable mass in right hypochondrium. Ultrasonography revealed a heterogenous mass in the lesser sac. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed features of gastric outlet obstruction with external compression. A provisional diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumour was made. The patient was initially treated conservatively with no relief. An exploratory laparotomy was undertaken and a mop was found in the subhepatic space, which had eroded the duodenum and a part of it was lying inside the duodenal lumen. The mop was extracted followed by duodenal closure, pyloric exclusion and gastro jejunostomy. However, the patient succumbed due to duodenal fistula and septicaemia.

Discussion

Gossypiboma (from Latin ‘gossipium’ cotton and Kiswahili ‘boma’ place of concealment) or retained surgical sponge is a ubiquitous medical error that is avoidable [7]. These retained sponges were first referred to as ‘textilomas’, but were renamed ‘gossypiboma’ in 1978. Gossypibomas are rarely documented owing to medical, legal and other reasons. Literature search showed that the reported foreign bodies retained in the abdominal cavity include sponges, towels, artery forceps, pieces of broken instruments or irrigation sets, rubber tubes, etc. [8].

Among the retained foreign bodies, surgical sponge constitutes the most-frequently encountered object because of its common use, size and amorphous structure [9]. Retained surgical sponge occurs at a frequency of one per 100–3,000 operations [10]. The three most significant risk factors are emergency surgery, unplanned change in the operation and body mass index. The presentation may be acute (within months) or chronic (within years). Acute generally follows a septic course with granuloma or abscess formation, whereas chronic presents in the form of adhesion or encapsulation [11, 12]. There is a case report of a 66-year-old man in whom gossypiboma was found after 24 years of gastrectomy [13]. The mechanism of erosion is apparently related to the surrounding inflammatory process and local adhesion of the bowel followed by necrosis and migration of the sponge within the bowel lumen [14]. As it enters into the lumen the entry point gets occluded [15]. This process usually takes weeks or years to occur. It is discovered eventually because of its complications. Among the complications reported are obstruction, peritonitis, adhesion, fistulas, abscess formation, erosion into gastrointestinal tract or extrusion of laparotomy pad via the rectum [16, 17]. Crossen and Crossen [18] collected a number of cases in which intraperitoneal sponges had eroded in the bowel and passed per rectum (37 cases), had to be removed surgically (24 cases) or were in the process of eroding the bowel lumen (10 cases). The patients usually present with pain, fever, constipation, abdominal mass, bleeding, etc. Continued pain in the postoperative period can signal a retained foreign body. A careful examination of a plain abdominal roentgenogram can be diagnostic. A whirl-like pattern has been described characteristic of retained sponges (due to gas entrapment in between the fibres) [7]. Ultrasound usually shows a well-delineated mass containing wavy internal echo with a hypoechoic rim and a strong posterior acoustic shadowing [19]. A computed tomography scan demonstrates a rounded mass with a dense central part and an enhancing wall [20]. On magnetic resonance imaging, a retained sponge is typically seen as a soft-tissue mass with a thick, well-defined capsule and a whorled internal configuration on T2-weighted imaging [21].

Prevention of gossypiboma can be done by maintaining standard recommendations [22–26]. It can be decreased by keeping a thorough count at least thrice (preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative), especially during emergency operation; complete exploration of abdominal cavity by the surgeon before closure if there is any doubt in the counts. As per WHO recommendation, count should always be done separately in a consistent sequence by two similar persons with their name being noted in the count sheet or nursing record. Methodical exploration of surgical wound by the operating surgeon decreases the likelihood of leaving sponges [27]. Immediate intraoperative X-rays should be done if there is suspicion in count. Newer technologies for detection include two-dimensional bar code, radiofrequency detector, and radiofrequency identification. The two-dimensional bar code system was the first technological approach. It incorporates a specific code to each sponge, which prevents double count. The second technological approach was radiofrequency detector where sponges are identified by radiofrequency beacons. These beacons cause base station to produce a beep when they remain underneath. Radiofrequency identification is a modification of radiofrequency detector where a tag is attached to each sponge. The surgical sponge is incorporated with radiopaque markers (density equivalent to 0.1 g/cm sup BaSO4) in between layers or strips or outside fibres, magnetomechanical tag, electronic tags, coloured fibres. They can be identified intraoperatively with help of X-ray films, magnets, and specific colours.

Medicolegal Aspect

Professional negligence is defined as the breach of duty caused by the omission to do something that a reasonable man, guided by those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something that a prudent and reasonable man would not do. Medical negligence or malpractice is defined as lack of reasonable care and skill, or wilful negligence on the part of a doctor in the treatment of a patient whereby the health or life of a patient is endangered. Article 21 of the Constitution says, ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law’. The Supreme Court held that ‘Thus, a doctor can’t be held criminally responsible for patient death, unless his negligence or incompetence showed such disregard for life and safety of his patient as to amount to a crime against the State’. Court further says that, ‘Thus, when a patient agrees to go for a medical treatment or surgical operation, every careless act of the medical man can’t be termed as “Criminal”. It can be termed as “Criminal” only when the medical man exhibits a gross lack of competence or inaction and wanton indifference to his patient’s safety and which is found to have arisen from gross ignorance or gross negligence. The legal position is almost firmly established that where a patient dies due to the negligent medical treatment of the doctor, the doctor can be made liable in civil law for paying compensation and damages in “Tort” and at the same time, if the degree of the negligence is so gross and his act was reckless as to endanger the life of the patient, he would also be made criminally liable for offence under section 304-A of IPC’. The normal rule is that it is for the plaintiff to prove negligence, but, in some cases, considerable hardship is caused to the plaintiff, as the true cause of the accident is not known to him, but is solely within the knowledge of the defendant who caused it. The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur [28, 29] means ‘that the accident speaks for itself or tells its own story’.

There is little question that the standard of care has been breached. The plaintiff can prove the accident, but cannot prove how it happened (so as) to establish negligence on the part of the defendant. While these cases are difficult, the surgeon can be exonerated or shown to be a minor player in this unfortunate drama.

The Court noted that as citizens become increasingly conscious of their rights, they are filing more cases against doctors in the civil courts, as also under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986, alleging ‘deficiency in service’.

Furthermore, doctors are being prosecuted under Section 304A of the IPC (causing death of any person by doing any rash or negligent act that does not amount to culpable homicide), which is punishable with imprisonment for a term that may extend to 2 years. They are also being prosecuted under Section 336 (rash or negligent act endangering human life), Section 337 (causing hurt to any person by doing any rash or negligent act as would endanger human life) or Section 338 of the IPC (causing grievous hurt to any person by doing any rash or negligent act so as to endanger human life).

Professional indemnity insurance cover became available for doctors and medical establishments only recently, that is, from December, 1991.

Conclusion

Medical and legal problems between the patient and the doctor may arise because of retained surgical sponge. Emergency surgery, unexpected change in the surgical procedure, disorganization, hurried sponge count, long operation, unstable patient condition, inexperienced staff, inadequate staff numbers, and patient with high body mass index are the possible excuses of retained surgical sponge, which is not desired [10]. Incorrect preoperative diagnosis may invite unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures and operations. Patient–clinician and clinician–radiologist interactions and compliance enhance the possibility of accurate diagnosis. The presence of a foreign body inside the patient can be easily proved and the patient may litigate the responsible surgeon, and the surgeon will face the tremendous mental agony, humiliation and also charges of negligence. The loss of reputation suffered by a doctor cannot be compensated by any standards. Human body and medical science both are too complex to be easily understood. Every surgical operation is attended by risks. We cannot take the benefits without taking the risks. Doctors, like the rest of us, have to learn by experience, and experience often teaches in a hard way [7]. The purpose of holding a professional liable for his/her act or omission, if negligent, is to make life safer and to eliminate the possibility of recurrence of negligence in future. To hold in favour of existence of negligence, associated with the action or inaction of a medical professional, requires an in-depth understanding of the working of a professional as also the nature of the job and of the errors committed by chance, which do not necessarily involve the element of culpability. Doctors and medical practice have to be treated in a different way. A private complaint may not be entertained unless the complainant produces prima facie evidence. Statutory rules need to be framed by the Government of India and State governments in consultation with Medical Council of India. This unwanted situation is entirely preventable. The services provided by a doctor are the noblest of all. The surgeon should always remain vigilant and cautious, as the damage done once, is done forever. Hence, prevention always remains better than cure.

References

- 1.IV (2006) CPJ 105 NC Bench: S G Member, P Shenoy K Ravindra Nath (Dr) And Anr. vs Vitta Veera Surya Prakasam And Ors. on 17/8/2006

- 2.Stawicki SP, Evans DC, Cipolla J, Seamon MJ, Lukaszczyk JJ, Prosciak MP, et al. Retained surgical foreign bodies: a comprehensive review of risks and preventive strategies. Scard J Surg. 2009;98:8–17. doi: 10.1177/145749690909800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dakubo J, Clegg-Lamptey JN, Hodasi WM, Obaka HE, Toboh H, Asempa W. An intra-abdominal grossypiboma. Ghana Med J. 2009;43(1):43–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qamar SA, Jamil M, Idress T, Sobia H. Retained foreign bodies after intra-abdominal surgery: a continuing problem. Prof Med J. 2010;17(2):218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paramythiotis D, Michalopoulos A, Papadopoulos VN, Panagiotou D, Papaefthymiou L, et al (2011) Gossypiboma presenting as mesosigmoid abscess: an experimental study. Tech Coloproctol (Suppl 1):S67–S69 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Tarik U, Gokhan DM, Sunay YM, Mahmut A (2009) The medico-legal importance of gossypiboma. 4thMediterranean Academy of Forensic Science Meeting, 14–18 October 2008, Antalya-Turkey. Abstract CD of Poster Presentations:82–83

- 7.Kokubo T, Itai Y, Ohtomo K, Yoshikawa K, Iio M, Atomi Y. Retained surgical sponges: CT and US appearance. Radiology. 1987;165:415–418. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.2.3310095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fair GL. Foreign bodies in abdomen causing obstruction. Am J Surg. 1953;86:472–475. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(53)90465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.William RG, Bragg RG, Nelson JA. Gossypiboma—the problem of the retained surgical sponge. Radiology. 1978;129:323–326. doi: 10.1148/129.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser CW, Friedman S, Spurling KP, Slowick T, Kaiser HA. The retained surgical sponge. Ann Surg. 1996;224:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarker MM, Golam Kibria AKM, Haque MM, Sarker KP, Rahman MK. Spontaneous transmural migration of a retained surgical mop into the small intestinal lumen causing sub-acute intestinal obstruction: a case report. TAJ. 2006;19(1):34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta NM, Chaudhary A, Nanda V, Malik AK. Retained surgical sponge after laparotomy, unusual presentation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:451–453. doi: 10.1007/BF02560235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota A, Haniuda N, et al. A case of retained surgical sponge (gossypiboma) and MRI features. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2000;33:1719–1723. doi: 10.5833/jjgs.33.1719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson KB, Levin EJ. Erosion of retained surgical sponges into the intestine. AJR. 1966;96:339–343. doi: 10.2214/ajr.96.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Düx M, Ganten M, Lubienski A, Grenacher L. Retained surgical sponge with migration into the duodenum and persistent duodenal fistula. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:874–877. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyslop J, Maull K. Natural history of retained surgical sponges. South Med J. 1982;75:657–660. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason LB. Migration of surgical sponge into small intestine. JAMA. 1968;205:122–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crossen HA, Crossen DF. Foreign bodies left in the abdomen. St Louis: CV Mosby Co; 1940. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chau WK, Lai KH, Lo KJ. Sonographic findings of intra-abdominal foreign bodies due to retained gauze. Gastrointest Radiol. 1984;9:61–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01887803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheward JE, Williams AG, Mettler FA. CT appearance of a surgically retained towel; (Gossypiboma) J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:343–345. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198603000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naik KS, Carrington BM, Yates W, Clarke NW. The post-cystectomy pseudotumour sign: MRI appearances of a modified chronic pelvic haematoma due to retained haemostatic gauze. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:970–974. doi: 10.1053/crad.2000.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Association of Theatre Nurses (2005) Swab, instrument and needles count. In: NATN standards and recommendations for safe perioperative practice. Harrogate, pp 233–237 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses (2007) Recommended practices for sponge, sharp, and instrument counts. In: Standards, recommended practices and guidelines. AORN Inc., Denver, CO, pp 493–502

- 24.Australian College of Operating Room Nurses and Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses (2006) Counting of accountable items used during surgery. In: Standards for perioperative nurses. ACORN, O’Halloran Hill, South Australia, pp 1–12

- 25.Operating Room Nurses Association of Canada (2007) Surgical counts. In: Recommended standards, guidelines, and position statements for perioperative nursing practice. Canadian Standards Association, Mississauga

- 26.South African Theatre Nurse (2007) Swab, instrument and needle counts. In: Guidelines for basic theatre procedures. Panorama, South Africa

- 27.American College of Surgeons. Statement on the prevention of retained foreign bodies after surgery. http://www.facs.org/fellows_info/statements/st-51.html (accessed 5 February 2008) [PubMed]

- 28.Berlin L. Malpractice issues in radiology: res ipsa loquitur. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(6):1475–1480. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal BB. A self-tailored hernia mesh using lightweight material: a note of caution—res ipsa loquitur. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(7):1684–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]