Abstract

Objective

To identify frames of interaction that allow smoking cessation advice in general practice consultations.

Design

Qualitative study based on individual in-depth interviews with GPs and their patients. Each of the GPs’ consultations were observed during a three-day period. Interviews primarily addressed the consultations that had been observed. The concept of “frames” described by Goffman was deployed as an analytic tool.

Setting

Danish general practice.

Subjects

Six GPs and 11 of their patients.

Results

Both GPs and patients evaluated potential issues to be included during consultations by relevance criteria. Relevance criteria served the purpose of limiting the number of issues in individual consultations. Issues could be included if they connected to something already communicated in a consultation. Smoking cessation advice was subject to these relevance criteria and was primarily discussed if it posed a particular risk to a particular patient. Smoking cessation advice also occurred in conversations addressing the patient's well-being. If occurring without any other readable frame, smoking cessation advice was apt to be perceived by patients as part of a public campaign.

Conclusions

Relevance criteria in the shape of communication of particular risks to particular patients and small-talk about well-being reflect the concept of “frames” by Goffman. Criteria of relevance limit the number of issues in individual consultations. Relevance criteria may explain why smoking cessation advice has not yet been implemented in many more consultations.

Key Words: Advice, family practice, general practice, Goffman, mass strategy, qualitative study, smoking cessation

A mass strategy of smoking cessation has been recommended for years but has yet not been implemented.

Relevance criteria are regulating which issues are included in the consultation by GPs and patients.

Relevance criteria included not only smoking-related illness but also other kinds of occasions such as discussions of patients’ well-being.

The findings of this study suggest that smoking cessation advice should not be part of every consultation.

Implementation of a mass strategy of smoking cessation advice in general practice consultations is recommended [1–4]. A mass strategy implies advice to all patients [5]. Consequently, consultations for diagnoses not related to smoking are regarded as “missed opportunities” [6].

General practitioners (GPs) primarily advise on smoking cessation when patients suffer from smoking-related disease, i.e. diseases due to smoking or relieved by smoking cessation [6–11]. They prefer to connect a discussion of smoking to the patient's problems [12]. Freeman [13] describes how GPs either link lifestyle advice to manifest illness or completely separate advice from issues in the consultation. Thus, GPs carefully determine the appropriateness of advice [14].

The present study uses Goffman's concepts to describe the interaction order of everyday life, including “frames” of interaction [15,16]. Frames are shared understandings of the meanings of the interaction in the encounter between individuals [17].

This study investigates frames of interaction in Danish general practice consultations challenged by the introduction of a mass strategy of smoking cessation advice. It aims to identify frames of interaction that allow smoking cessation advice in consultations.

Material and methods

Interviews with GPs and patients were grounded in observation of their own consultations. Observations and interviews contributed knowledge on when and how smoking cessation advice did or did not occur and why the issue was raised or avoided.

Selection of GPs

Eighteen GPs were invited with the aim of arriving at a total of six GPs who wanted to participate. Recruitment followed the principle of maximal variation [18] primarily regarding activity of smoking cessation advice but also of sex, duration of practice tenure, and urban/rural practices (Table I). Including a less active male GP with short practice tenure proved difficult. Among the 12 GPs who declined participation, seven were less active male GPs with short practice tenure. The other five GPs who did not participate were both active and less active male and female GPs with longer practice tenure. GPs’ level of activity was identified by local public administrators responsible for smoking cessation and by colleagues according to the principles of member-identified categories described by Hammersley and Atkinson [19] and Kuzel [20]. All GPs accepted their peers’ assessment.

Table I.

Characteristics of the selected GPs.

| GP | More active | District (no) | Sex (M/F) | Age (yrs) | Tenure in practice (years) | In partnership surgery | Postgraduate training in smoking cessation |

| A | Yes | 1 | M | 55 | 23 | Yes | No1 |

| B | No | 1 | F | 46 | 4 | Yes | No |

| C | Yes | 2 | F | 45 | 6 | Yes | Yes1 |

| D | No | 2 | M | 59 | 29 | Yes | No |

| E | Yes | 3 | M | 50 | 15 | No | Yes |

| F | No | 3 | M | 43 | 7 | No | No |

Notes: Districts are indicated by numbers. 1Had a smoking cessation counsellor in their practice.

Observations

The consultations of six GPs were observed, each during a three-day period. Observational, theoretical, and methodological notes were taken according to the principles of Schatzman and Strauss [21]. Observation and interviews were carried out during 2003–2004.

Selection of consultations and of patients for interview

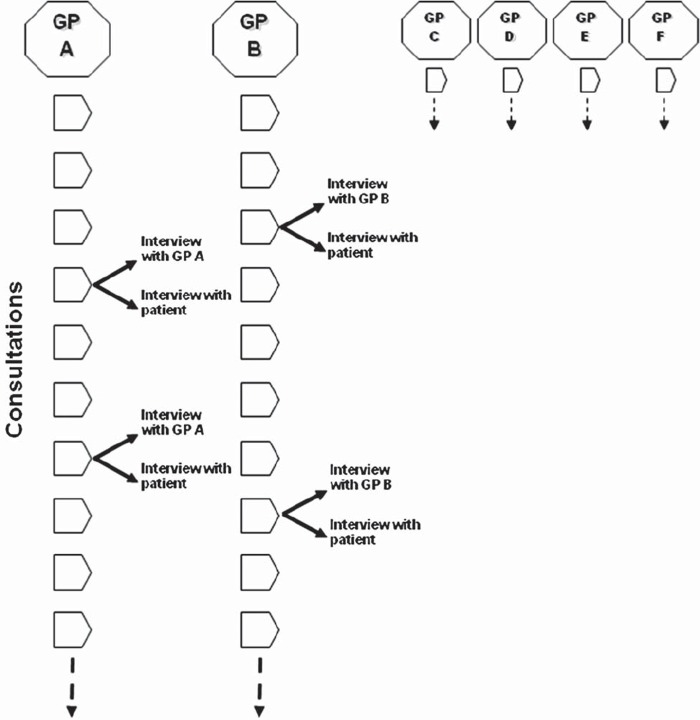

Based on observations, a strategic sample of consultations from each practice was selected for further investigation through interviews with GP and patient respectively (Figure 1). The strategic sample was aiming at consultations regarding health problems not related to smoking. These consultations were given special attention by interviews because, according to a mass strategy, they are supposed to contain advice but, according to the literature, they usually do not. Patients’ sex, age, and health problems were also selection criteria, aiming at a maximal variation of these parameters. Finally, only consultations with patients who were considered smokers or potential smokers by their GP were selected. This procedure ensured that only patients considered appropriate candidates for advice by the GPs were included.

Figure 1.

Design: Consultations with GPs A, B, C, D, E, and F were observed. Interviews with the GPs and with their patients were grounded on these consultations.

Thirteen patients were asked for an interview and nine of them accepted. Two patients who had been attending with smoking-related health issues but did not receive any advice were interviewed as well. The consultations of all 15 patients were included in the analysis.

Definition of smoking-related symptoms or illnesses

Symptoms or illnesses diagnosed by the GPs were defined as smoking-related if smoking might have developed or shaped the illness course or if cessation was known to improve the prognosis. Knowledge of the relationship between smoking and symptoms or illnesses was searched for in national and international literature through repeated literature searches during the study.

Definition of smoking cessation advice

Smoking cessation advice was defined as any discussion of smoking that went beyond answers to the GP's anamnestic questions regarding the patient's smoking status, the amount of tobacco smoked, and the duration of consumption [22].

Interviews

After observations, patients selected for interviews were contacted by phone. Characteristics of these patients are given in Table II. Semi-structured interviews were conducted as soon as possible after their consultation [23]. At the beginning of the interview all participants were invited to listen to the audio record of the consultation, and most accepted this invitation. The questions concerned the GP's motives for discussing smoking in the particular consultation or leaving it out as well as what aspects might, in general, make the GP raise the issue. Questions also explored how smoking cessation advice was communicated, and whether the patients had ever felt that advice was lacking from a consultation. Questions to patients and to GPs covered the same issues in wording appropriate for the two perspectives. The consultations that had been observed served as a shared frame of reference between the interviewer and the interviewee.

Table II.

Patients interviewed.

| Patient | Health problem | Advice in present consultation | Age, years |

| Sharon | Inflammation of the throat | Yes | 34 |

| Gerald | Urination at night | No | 60 |

| Jane | Cystitis or vaginitis | No | 48 |

| Sophie | Stress and perfectionism | No | 33 |

| Roxanne | Inflammation of the throat | Yes | 18 |

| Charles | Wart | No | 78 |

| Alice | Neck and back pain | No | 61 |

| John | Haemorrhoids | Yes | 57 |

| Mary-Ann | Contraceptives | No | 35 |

| Monica | Pityriasis | No | 66 |

| Dave | Possible venereal disease | No | 23 |

Analysis

All interviews and the selected consultations were transcribed verbatim. Coding was based on the informants’ own categories, inspired by Giorgi's four-step process [24]. The analysis focused on the interaction order in the consultations agreed upon by patients and GPs. Individual transcripts were read to get a sense of the whole statement, and text units addressing specific issues were coded. The text units were organized in common themes. For example the text units coded as “the health problem in question” were included in a common theme of “occasion for advice”. During the course of this reduction process, individual codes utilized only once or only a few times were excluded. The common themes were collapsed into main themes. The main theme of “relevance criteria” was based on the common themes of “occasion for advice”, “advice related”, “advice because”, “iatrotropic threshold”, “medical priority”, “scarcity”, “GP's knowledge of the patient's smoking status”, “good situations for smoking cessation advice”, and, finally, the theme of “the patient's belief in relation to smoking”.

Goffman's concept of “frames” offered a theoretical perspective on the mechanisms by which GPs and patients ordered the interaction during consultations. Frames are definitions of situations. Participants in an encounter arrive at a working consensus regarding their meeting by negotiating within these frames [17, p. 41]. In a particular setting, as in general practice consultations, a rather stable pattern of actions is established as an interaction order [15,16]. This perspective was useful in explaining the inclusion and exclusion of particular issues in the consultations.

The analytical process was triangulated [25] between the authors and one additional researcher. Analysis was carried out using NVivo software.

The study was a part of a larger research project on the GP–patient relationship and smoking cessation advice. The results concerning morality and the results concerning the maintenance of trust during interaction have been reported in separate papers [26,27]

Results

Relevance criteria

Smoking cessation advice was judged by relevance criteria prior to inclusion. The relevance criteria applied to all potential issues for discussion during consultations. They worked as frames of interpretation. The relevance criteria allowed an issue to be included by connecting it to issues already raised. For instance, GPs and patients found that smoking cessation advice fitted naturally with smoking-related illnesses or symptoms such as coughs or diabetes. To illustrate how advice is communicated in relation to a health problem we quote from a consultation with a woman presenting with allergy. Her former GP suspected she had asthma:

Mona: Then he gave me some pills to try out…

GP B: Some pills?

Mona: Yes, and then he asked if it had been of any help, and when I told him that it had, I got some kind of gadget, I had to … to suck.

GP B: Yes, but it's been a long time since you've used it.

Mona: Yes.

GP B: Yes well, I would like it if you had one made here as well to see the … how you…. I seem to remember that you're a smoker, aren't you? How much do you smoke?

Mona: I think I've reduced it to ten now.

GP B: Ten, yes. That's also something that can really be a part of … making the asthma worse, that you put smoke down there, that makes the body react, you know.

In this case, possible asthma made advice relevant. On another occasion the topic of smoking was introduced after the GP had finished inserting acupuncture needles for treating infiltrations in the neck:

GP C: That one was really tender – is that where you've had the most pain?

Edith: A little … I think so.

GP C: Are you all right?

Edith: Yes.

GP C: You're not getting unwell?

Edith: No.

GP C: No…. Should I stick some in your ears for smoking cessation?

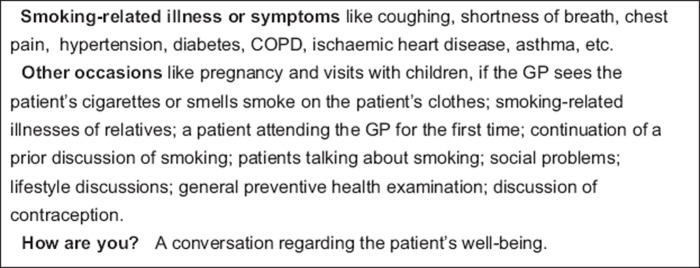

In this case, the relevance of smoking cessation advice was linked to the practice of acupuncture. Advice also occurred as follow-up on prior discussions of smoking, or when GPs met patients for the first time. Most patients were puzzled if their GP raised the subject of smoking when they could not discern the relevance rooted in the actual consultation. The relevance criteria identified in this study are presented in Figure 2. According to GPs and patients, relevance criteria had the function of limiting the number of issues that could be raised during consultations. GPs felt that the number of issues they ought to raise by far exceeded what could possibly be discussed in the limited time allowed. Smoking was one of these issues. Consultations in Denmark typically last 10 or 15 minutes. Smoking cessation advice would primarily be given when GPs found that the contents of the consultations provided an occasion to give it.

Figure 2.

Relevance criteria for smoking cessation advice.

Particular risks

Patients distinguished individual smoking cessation advice from general information to the public:

Jane: If [smoking turned up when I attended with a swollen finger] then I would think … that it was probably part of some public campaign that was going on at the time.

Similar points were made by several patients. Smoking cessation advice directed at all patients would be perceived as different from normal communication in general practices. As long as smoking was not associated with any issues in the consultation, patients would consider advice as a part of a current public campaign, and hence associate it with radio and TV spots or warnings on cigarette packs. Thus, if smoking cessation advice did not fit the relevance criteria in the consultation, the frame of interpretation would change from one regarding particular risks communicated to particular patients to one of a current health campaign with information relevant to anybody. For patients, individual and general advice have very different implications. The following quote illustrates the implications of smoking cessation advice for patients when it is not clear that the advice is directed to everybody rather than being particular to the individual patient:

Mary-Ann: Do I look like that? Or do I have any symptoms or signs of disease that make the GP think that something's wrong? I think I would feel that way if he asked me, without any reason, if I was a smoker. Like “God, does he think that I've got lung cancer?” or, … I'd be worried.

Small-talk

Some consultations included what patients termed “small-talk”, meaning that patients asked health questions of a general nature or spoke about their everyday life:

Cheryl: Those are the kind of days where I decide to just relax, just be myself with my dog, right. And I am. I have the answering machine turned on, on the phone. Just in case something should happen to my father or my daughter or something like that. It feels good to just go in and listen to it, now and then, right. But otherwise, yes, that's what I do.

GP B: You once talked about doing something about smoking too?

According to GPs and patients, smoking cessation advice sometimes occurred in such discussions of well-being. The GPs also considered these discussions as a professional activity. They asked questions about work, family, well-being, and interests. The knowledge obtained was used to become familiar with the patients’ perception of their own health. Moreover, GPs could better adapt their interventions to the patient's circumstances when they had gained this knowledge. Small-talk was, however, optional and often occurred in “spare time”, as for example when GP C was awaiting the effect of the acupuncture.

Discussion

Frames

Criteria of relevance, for instance communicating particular risks to particular patients and small-talk, are examples of Goffman's concept of frames [16]. Frames are the meanings attached to the patient's and the GP's understandings of the occurrence of smoking cessation advice. Criteria of relevance are frames of interpretation, which explain why smoking was brought up, and what the GP aimed at in the particular situation. Frames situate smoking cessation advice in a meaningful context to the parties involved.

Particular risks, well-being, or public campaign

GPs’ traditional strategy of smoking cessation advice has been described as focused on smoking-related illnesses [6–11]. In this study, smoking-related illness was the main relevance criterion. GPs perceived lack of smoking cessation advice to patients with such illnesses as a failure of their own work. However, GPs found other occasions for providing smoking cessation advice in general practice. If advice, however, was not given within a recognizable frame of reference, patients were likely to perceive advice as part of a public campaign and hence not particularly important to themselves.

This study supports the findings of previous surveys arguing that smoking cessation advice is given in the context of smoking-related illness. It also adds that advice should occur on many other occasions, and may be displayed as a part of the GPs’ interest in patients’ well-being.

Moreover, this study adds to the description offered by Sorjonen et al. [28] that lifestyle issues raised in relation to illness tended to be given further attention in the consultations. When raised out of this context, lifestyle issues usually did not achieve the status of being an important problem to be dealt with. The interviews with GPs and patients in this study added the function that these actions had in limiting the number of issues raised in a consultation. This finding is particularly relevant since the amount of opportunistic preventive issues that may be addressed has grown to such an extent that they may compete with other core activities in consultations [29].

Relevance criteria may explain why smoking cessation advice has not yet been implemented in many more consultations. The results of this study indicate that interactional barriers are limiting the extent of smoking cessation advice. These barriers, however, serve a purpose in the interaction order of consultations and cannot be eliminated without side effects on the interaction as a whole. From this perspective, it cannot be considered that every consultation without smoking cessation advice is a “missed opportunity”.

How do the present findings match surveys reporting that most patients believe that physicians are also responsible for providing smoking cessation advice when it is not linked to smoking-related illness [30,31]? The present study addresses the practical implementation of advice from the perspective of a single consultation, thereby shifting the focus from “if” to “how” advice occurs. Rather than evaluating whether smoking cessation advice belongs in general practice, patients and GPs describe the scene that already exists for communicating advice in consultations.

Generalizability

In this small, qualitative study the analysis is not based on a representative sample of GPs and patients. The findings are thus not generalizable to all GPs and patients. The study is, however, based on a sample of GPs with different levels of commitment to smoking cessation advice and also included a number of their patients. The themes prevailing in this sample are thus probably relevant to GPs and patients beyond the sample in question.

The study was conducted in Danish general practice, and so it is inevitably influenced by the structure of GP surgeries in Denmark. General practice consultations in other countries are either shorter (the UK) or longer (Sweden). This difference probably affects how time in the consultation is experienced. In most countries, however, access to GPs is still limited and prioritized according to severity, stressing the importance of scarcity of time.

Limitations

Attitudes to smoking have changed significantly in recent years. This probably affects the way that smoking cessation advice is handled in general practice. The increased attention to smoking may make it easier to find frames for smoking cessation advice during consultations. It may, however, be at the expense of the gravity that has hitherto been ascribed to the GP's advice when aiming at particular health risks.

Many aspects other than criteria of relevance should be considered in determining the appropriateness of advice in consultations, such as patients’ readiness to change and establishing rapport [32].

Conclusion

Smoking cessation advice in general practice consultations is given in the context of smoking-related illness but advice occurs on many other occasions. Criteria of relevance limit the number of issues in individual consultations. They apply to smoking cessation advice as well as to any other issue considered for inclusion in a specific consultation.

Implications

Implications of these findings for a mass strategy of smoking cessation advice are that in consultations without smoking-related illness, advice would need other relevance criteria to fit the frames of the interaction order in Danish general practice consultations. Considering the frames of interaction identified in this study, smoking cessation advice should not be part of every consultation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the GPs and the patients who kindly participated in this study. Ann Dorrit Guassora also wishes to thank the supervisors of her PhD study MA phil. dr. Thorkil Thorsen, MD PhD MHPE Anne Charlotte Tulinius and MS dr.scient.soc. Dorte Gannik for their great help and encouragement.

Ethical approval

The information given to participants in the study and the procedure concerning consent were approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Funding

The study was accomplished thanks to funding from the Danish Research Foundation for General Practice and from the Fund of Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellsborg.

Conflict of interests

None.

References

- 1.Danish National Board of Health and National Center for Smoking Cessation. [Sundhedsstyrelsen og Nationalt Center for Rygestop] Methods for smoking cessation – documentation and recommendations. Copenhagen: Sundhedsstyrelsen og Nationalt Center for Rygestop; 2003. [Metoder til rygeafvænning – dokumentation og anbefalinger] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raw M, McNeill A, West R. Smoking cessation: Evidence based recommendations for the health care system. BMJ. 1999;318:182–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: An update. Thorax. 2000;55:987–99. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. Issue 2. Art. No. CD000165. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1981;282:18–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. National patterns in the treatment of smokers by physicians. JAMA. 1998;279:604–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman T, Cheater F, Murphy E. Qualitative study investigating the process of giving anti-smoking advice in general practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:159–63. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn A, Coleman T, Barrett S, Wilson A. Factors associated with the provision of anti-smoking advice in general practice consultations. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:997–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallefoss F, Drangsholt K. Smoking cessation intervention and barriers to intervention among general practitioners in Vest-Agder. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen. 2002;27:2608–11. [Røykeintervensjon og hindringer for dette blant fastleger i Vest-Agder] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawlor DA, Keen S, Neal RD. Can general practitioners influence the nation's health through a population approach to provision of lifestyle advice? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:455–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helgason AR, Lund KE. General practitioners’ perceived barriers to smoking cessation – results from four Nordic countries. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30:141–7. doi: 10.1080/14034940210133799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman T, Wilson A. Anti-smoking advice in general practice consultations: General practitioners’ attitudes, reported practice and perceived problems. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:87–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman SH. Health promotion talk in family practice encounters. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:961–6. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman T, Murphy E, Cheater F. Factors influencing discussion of smoking between general practitioners and patients who smoke: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:207–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goffman E. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books; 1959. The presentation of self in everyday life. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goffman E. New York: Harper & Row; 1974. Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. North-eastern University Press ed.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grbich C. Vol. 41. London: Sage Publications; 1999. Qualitative research in health: An introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malterud K. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2003. Qualitative methods in medical research – an introduction. [Kvalitative metoder i medicinsk forskning – en innføring] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Research design: Problems, cases and samples. In: Hammersley M, Atkinson P, editors. Ethnography: Principles in practice. London: Tavistock Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. 2nd ed. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schatzman Leonard, Strauss Anselm L. Strategies for a natural sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1973. Strategy for recording. In: Field research. Ch. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swedish National Committee for Evaluation of Medical Methods [Statens beredning för utvärdering av medicinsk metodik] Stockholm: SBU; 1998. Methods for smoking cessation. [Metoder for rökavvänjning] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kvale S. London: Sage Publications; 2007. Doing interviews. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giorgi A. Sketch of a psychological phenomenological method. In: Giorgi A, editor. Phenomenology and psychological research. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1984. Qualitative data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guassora AD, Tulinius AC. Keeping morality out and the GP in: Consultations in Danish general practice as a context for smoking cessation advice. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guassora AD, Gannik DE. The process of developing and maintaining patients’ trust in general practice consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorjonen ML, Raevaara L, Haakana M, Tammi T, Peräkylä A. Lifestyle discussions in medical interviews. In: Heritage J, Maynard DW, editors. Communication in medical care: Interaction between primary care physicians and patients. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Getz L, Sigurdsson JA, Hetlevik I. Is opportunistic disease prevention in the consultation ethically justifiable? Education and debate. BMJ. 2003;327:498–500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7413.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bremberg S, Nilstun T. Justification of physicians’ choice of action: Attitudes among the general public, GPs and oncologists in Sweden. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23:102–8. doi: 10.1080/02813430510018455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Danish National Board of Health [Sundhedsstyrelsen] Copenhagen: Sundhedsstyrelsen; 2008. Smoking habits in Denmark 2008 [Danskernes rygevaner 2008] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. Health behavior change – a guide for practitioners. [Google Scholar]