Abstract

Introduction

Sorafenib is a raf kinase and angiogenesis inhibitor with activity in multiple cancers. This phase II study in heavily pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (≥ two prior therapies) utilized a randomized discontinuation design.

Methods

Patients received 400 mg of sorafenib orally twice daily for two cycles (two months) (Step 1). Responding patients on Step 1 continued on sorafenib; progressing patients went off study, and patients with stable disease were randomized to placebo or sorafenib (Step 2), with crossover from placebo allowed upon progression. The primary endpoint of this study was the proportion of patients having stable or responding disease two months after randomization.

Results

: There were 299 patients evaluated for Step 1 with 81 eligible patients randomized on Step 2 who received sorafenib (n=50) or placebo (n=31). The two-month disease control rates following randomization were 54% and 23% for patients initially receiving sorafenib and placebo respectively, p=0.005. The hazard ratio for progression on Step 2 was 0.51 (95% CI 0.30, 0.87, p=0.014) favoring sorafenib. A trend in favor of overall survival with sorafenib was also observed (13.7 versus 9.0 months from time of randomization), HR 0.67 (95% CI 0.40-1.11), p=0.117. A dispensing error occurred which resulted in unblinding of some patients, but not before completion of the 8 week initial step 2 therapy. Toxicities were manageable and as expected.

Conclusions

: The results of this randomized discontinuation trial suggest that sorafenib has single agent activity in a heavily pretreated, enriched patient population with advanced NSCLC. These results support further investigation with sorafenib as a single agent in larger, randomized studies in NSCLC.

Keywords: NSCLC, sorafenib, randomized discontinuation trial

INTRODUCTION

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains a challenging disease with the highest cancer mortality in the United States for both men and women, and limited treatment options beyond first and second-line therapy.1, 2

Sorafenib is a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor with proven activity in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and hepatoma. It was originally discovered as an inhibitor of Raf-1 kinase, but was found to have an expanded target profile with potent activity against other kinases including B-Raf, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) -1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, platelet derived growth factor (PDGFR)-β, KIT, Flt-3, and RET.3-5 It has broad-spectrum efficacy in human tumor xenograft models including NSCLC. 6, 7

A continuous daily dosing regimen of 400 milligram (mg) orally twice daily (bid) has emerged as the phase II/III preference.8-10 Due to the cytostatic activity of this drug, a randomized discontinuation design was used in this trial to select out patients with rapidly progressive disease. Thus, only an enriched patient population with more slowly progressive disease is randomized, as in the landmark sorafenib renal cell carcinoma study.11-14 NSCLC seemed an ideal disease in which to further investigate sorafenib based on the frequency of Ras mutations, particularly in adenocarcinomas,15-17 and the known activity of the anti-VEGF agent bevacizumab. 18

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a randomized phase II discontinuation design study run through the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) at member institutions. All patients signed informed consent. The primary objective of this phase II study was to determine, in the subgroup of patients who had achieved stable disease after a two-month run-in period on sorafenib, the percent of patients maintaining stable disease or achieving an objective response after two-months continued sorafenib treatment compared to patients switched to placebo. Secondary objectives included evaluation of overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rate.

Patient Eligibility

Eligible patients had advanced stage NSCLC with disease progression after having received at least two prior chemotherapy regimens (prior epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKI) therapy was not counted as chemotherapy). Patients must have completed all therapy at least three weeks prior to study entry. Other requirements were minimum age of 18 years, a good performance status (ECOG Performance Status of 0 or 1) and good organ function; ANC >1500/mm3, platelet >100,000/mm3, bilirubin < 1·5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), AST (SGOT) and ALT (SGPT) < 3 × ULN (< 5 × ULN in patients with liver disease), creatinine < 1·5 × ULN or calculated creatinine clearance greater than 50 milliliters/minute). Patients with treated, stable brain metastases were eligible. Patients were excluded for active cardiac disease, active second malignancy, prior exposure to a Ras pathway inhibitor, or serious infection. Use of contraception was advised and pregnant or breast-feeding woman were excluded. Use of certain medications known to be inhibitors or inducers of the cytochrome p450 system CYP3A4 enzyme or other medications known to be metabolized by the liver with a narrow therapeutic index were prohibited, with close monitoring of patients taking any medications metabolized by the liver (warfarin).

Study Design and Treatments

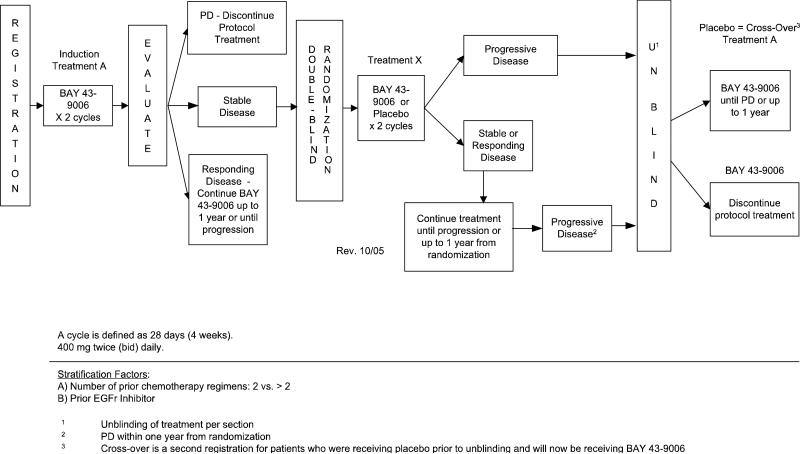

At baseline a complete history and physical, blood draw for laboratory parameters (complete blood counts, serum chemistries, pregnancy test), 12 lead EKG, and tumor measurements were required. Patients were seen at least monthly with repeat laboratory blood draws. Tumor measurements were repeated every two months. No other anti-cancer therapy was allowed for patients on trial. Sorafenib was given orally in tablet form at a dose of 400 mg twice daily (BID) on a continuous schedule to all patients enrolled on Step 1. A treatment cycle was defined as 28 days. As outline in Figure 1, after the two-month run-in period in which all patients received sorafenib, patients were eligible for randomization to sorafenib or placebo (Step 2) if they had stable disease. Patients were eligible for crossover (Step 3) if they had documented progressive disease on placebo (unblinded at progression). Patients who progressed during Step 1 came off study and those who had documented response continued on active drug until progression.

Figure 1.

Schema of study steps

Doses were delayed or reduced for clinically significant, treatment-related toxicities (toxicity grading per the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 3·0). All patients, including those who discontinued protocol therapy, were followed for response until progression and for overall survival.

After the run-in period, participating patients, medical staff, and ancillary medical staff were blinded to the assignment of sorafenib or placebo. The study was monitored by the ECOG Data Monitoring Committee.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint for this study was the proportion of patients having stable disease or objective response two months after randomization (step 2). Assuming that 35% of patients would remain stable during the run-in period, and allowing for 10% ineligibility, we estimated enrollment of 311 patients (280 eligible patients) in order to randomize 98, the enrollment objective. Stratification factors included prior treatment with chemotherapy and EGFR-TKIs. We assumed 49 eligible patients per arm for the primary endpoint analysis. If the true proportion of patients maintaining stable disease is 0.25 for the placebo, then this design would have approximately 91% power to detect a corresponding true proportion on the treatment arm of 0.56 or greater, based on a one-sided Fisher's exact test with α=0.05.

Tumor response was evaluated using RECIST 1.0 criteria at the end of every 2 cycles. Best overall response for each step was defined as the best response recorded from registration onto the step until registering onto next step or until disease progression/recurrence. Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of patients with either a complete response (CR) or a partial response (PR) among all eligible and treated patients. Disease control rate (DCR) was defined similarly except with CR+PR+SD (stable disease) as the numerator.

Progression-free survival (PFS) for each step was defined as the time from registration onto the step to disease progression or to death without documented progression. Patients without documented progression were censored at the time they were last known to be free of progression. Patients with unevaluable responses were censored at the time of registration onto the step. Due to the drug/placebo dispensing errors described below, patients switched to the opposite treatment on Step 2 were censored at date of treatment switch, if it occurred before disease progression. Overall survival (OS) for each step was defined as the time from the date of registration onto the step to death from any cause. Patients who were alive or lost to follow-up at the time of this analysis were censored at the date last known alive. Toxicities were graded according to the NCI CTCAE version 3.0. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patient demographics, disease characteristics, and adverse events. Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate differences in response rate, patient demographics, and disease characteristics between groups. Exact binomial 90% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for ORR and DCR. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to evaluate differences in age. The event-time curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the curves were compared using a stratified logrank test. The hazard ratio was estimated using a stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model. Due to drug/placebo dispensing errors described in the results section, comparisons of all endpoints looked at groups defined by the initial treatment actually received after randomization rather than the assigned treatment group. All p-values are two-sided except for the primary test. A level of 5% was considered statistically significant. All tests were performed using SAS 9.

RESULTS

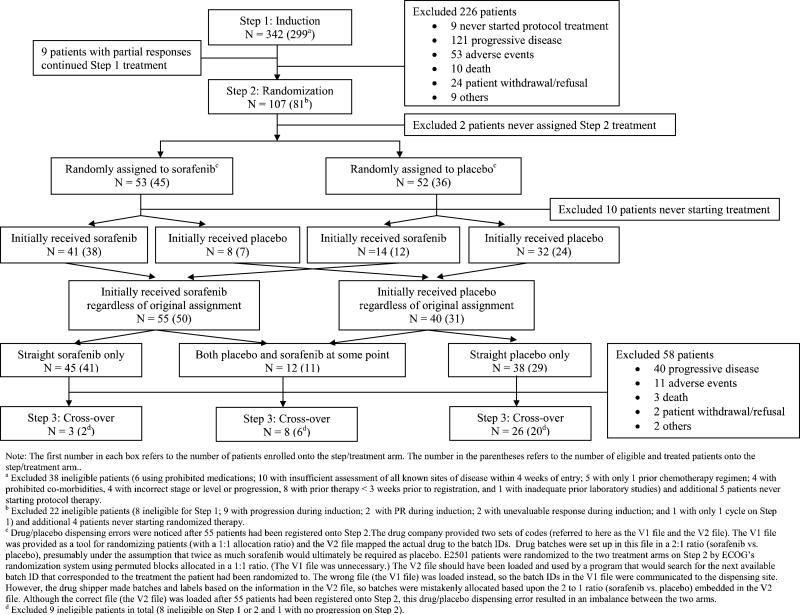

Between May 2004 and May 2007 342 patients were enrolled and treated with open label sorafenib (Step 1). After two cycles of therapy, 107 patients with stable disease were randomized (Step 2). A total of 37 patients subsequently crossed over to the study drug (Step 3) after having progressed on placebo. As outlined in Figure 2 consort diagram, there were 299 eligible and treated patients on Step 1, 81 eligible and treated patients on Step 2 (50 initially receiving sorafenib and 31 initially receiving placebo), and 28 eligible and treated patients on Step 3. All analyses were based on eligible and treated patients except for toxicity analysis, which was based on all treated patients regardless of eligibility status.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

Table 1 lists patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline by step. The demographics of those eligible for Step 2 did not differ between the sorafenib group and the placebo group and there were no imbalances in known prognostic factors.

Table 1.

Eligible and Treated Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics at Baseline by Step/Treatment

| Step 1 (N=299) | Step 2: Sorafenib (N=50) | Step 2: Placebo (N=31) | Step 3 (N=28) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | 168 | 56.4 | 23 | 46.0 | 18 | 58.1 | 17 | 60.7 |

| Male | ||||||||

| Female | 130 | 43.6 | 27 | 54.0 | 13 | 41.9 | 11 | 39.3 |

| Unknown | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Race | 271 | 92.5 | 45 | 93.8 | 28 | 90.3 | 25 | 89.3 |

| White | ||||||||

| Black | 13 | 4.4 | 2 | 4.2 | . | . | - | - |

| Asian | 9 | 3.1 | 1 | 2.1 | 3 | 9.7 | 3 | 10.7 |

| Unknown | 6 | - | 2 | - | . | . | - | - |

| Ethnicity | 6 | 2.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hispanic/Latino | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 269 | 97.5 | 47 | 94.0 | 30 | 96.8 | 27 | 100.0 |

| Institution refusal | 1 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unknown | 23 | - | 3 | 6.0 | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | - |

| PS | 102 | 34.1 | 21 | 42.0 | 12 | 38.7 | 10 | 35.7 |

| 0 | ||||||||

| 1 | 197 | 65.9 | 29 | 58.0 | 19 | 61.3 | 18 | 64.3 |

| Histology | 46 | 15.4 | 6 | 12.0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 14.3 |

| Squamous carcinoma | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 138 | 46.2 | 27 | 54.0 | 20 | 64.5 | 18 | 64.3 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 13 | 4.3 | . | . | 1 | 3.2 | 1 | 3.6 |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) | 10 | 3.3 | 2 | 4.0 | . | . | 1 | 3.6 |

| Non-Small cell lung cancer, NOS | 76 | 25.4 | 12 | 24.0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 14.3 |

| Combined/Mixed | 9 | 3.0 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 3.2 | - | - |

| Other | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 4.0 | 1 | 3.2 | - | - |

| Number of Prior Chemo Regimens (Based on BDFa) | 173 | 57.9 | 27 | 54.0 | 20 | 64.5 | 16 | 57.1 |

| 2 | ||||||||

| 3 | 72 | 24.1 | 12 | 24.0 | 6 | 19.4 | 8 | 28.6 |

| >=4 | 54 | 18.1 | 11 | 22.0 | 5 | 16.1 | 4 | 14.3 |

| Prior EGFR Inhibitor (Based on BDFa) | 136 | 45.5 | 26 | 52.0 | 19 | 61.3 | 11 | 39.3 |

| Number of Prior Chemo Regimens (Based on values on the stratification factor at registration) | - | - | 22 | 44.0 | 19 | 61.3 | - | - |

| 2 | ||||||||

| ≥ 2 | - | - | 28 | 56.0 | 12 | 38.7 | - | - |

| Prior EGFR Inhibitor (Based on values on the stratification factor at registration)b | - | - | 23 | 46.0 | 15 | 48.4 | - | - |

| Age: Median (Range) | 64 (33-86) | 64 5 (42-80) | 69 (40-86) | 69 (40-83) | ||||

BDF refers to Baseline Data Form.

Values on these stratification variables were used for statistical test.

Treatment

An error in which drug/placebo dispensing codes (on Step 2) were incorrectly loaded into ECOG's computer program was found after 55 patients had been enrolled on Step 2 (Figure 2) and is detailed below. ECOG notified all of the involved agencies regarding this error. As detailed in Figure 2, 41 of the 53 patients randomly assigned to sorafenib initially received the drug, and 8 received placebo. Of the 52 randomly assigned to placebo, 32 initially received placebo and 14 received sorafenib. In total, 55 (50 eligible) initially received sorafenib, regardless of randomization and 40 (31 eligible) initially received placebo. All patients continued on the initially received drug through the first 8-weeks of therapy as a 2-month supply was given. As detailed in Figure 2, after the initial 8-week therapy, the potential for drug switching occurred and 12 (11 eligible) patients were impacted and received both placebo and sorafenib at some point.

The 12 patients who received mixed drug/placebo treatments on Step 2 were informed by their physicians as soon as the error was identified, and offered either open-label sorafenib or taken off study treatment. Patients who were unblinded due to progression and who were found to be on placebo were notified immediately and offered open-label sorafenib.

The specific details of the dispensing errors are detailed in Figure 2. In brief, the pharmaceutical manufacturer provided two sets of codes to ECOG, the actual file (V2) which mapped drug to batch IDs and a separate code (V1) which was to be used to help with randomization. E2501 patients were randomized to the two treatment arms on Step 2 by ECOG's randomization system using permuted blocks allocated in a 1:1 ratio which made the code supplied for randomization (V1) unnecessary. Unfortunately the V1 file was loaded into the system, but the drug shipper made batches and labels based on the information in the V2 file. This error was identified after 55 patients had been registered onto Step 2 and the V2 file was then used, but this drug/placebo dispensing error resulted in an imbalance between the two arms.

Figure 2 displays the consort diagram based on treatment assigned and actually received. One patient remains on Step 1 treatment with sorafenib at 51 cycles at the time of this analysis. Of the 298 other eligible patients treated with sorafenib on Step 1, 89 (30%) completed the induction treatment, 116 (39%) and 51 (17%) patients came off, respectively, for disease progression and toxicity. Among the 81 eligible and treated patients on Step 2, 41 patients had straight sorafenib treatment, 29 had straight placebo treatment, and 11 had mixed treatment. The majority of Step 2 patients (73% on sorafenib; 93% on placebo; 36% mixed treatment) discontinued due to progression. There were three deaths as reason for coming off study in Step 2, two on sorafenib and one with mixed therapy. Seven patients (17%) on sorafenib stopped for toxicity and two (7%) on placebo. Of the 28 eligible and treated patients who crossed over to sorafenib on Step 3, 17 stopped due to progression and four due to death.

Toxicity

Table 2 lists any grade 1 or 2 treatment related toxicity see on Step 1 in at least 5% of patients, during which time all patients received sorafenib and additionally lists grade 3 and 4 toxicity which were possibly, probably, or definitely related to treatment and were seen in at least 1% of patients on Step 1 or in more than one patient on Step 2 or 3. During Step 1, 13 patients (4%) had grade 4 toxicities and 112 (34%) had grade 3 toxicities. The most common grade 4 toxicity was thrombosis/ thrombus/ embolism (2%). The most common grade 3 toxicities were fatigue (10%), hand-foot reaction (10%), and rash/desquamation (6%). Two patients on Step 2 had grade 4 toxicities (one with hemoglobin and the other with central nervous system cerebrovascular ischemia) and 23 patients had grade 3 toxicities with twice as many on the sorafenib versus placebo arm. Of the 35 patients treated on Step 3, there were 14 cases (40%) of grade 3 toxicity, mostly fatigue, and no grade 4 toxicity reported. There were no significant differences in toxicity by histology (squamous versus non-squamous) in induction treatment. No statistical test for histology was performed for Step 2 and 3 due to low numbers of squamous cases in each arm or step.

Table 2.

Treatment-related toxicity including all Grade 1/2 toxicity occurring in at least 5% of all enrolled and treated patients on Step 1; and Grade 3/4 toxicity at least possibly related to study treatment and of at least 1% on step 1 or in at least 1 pt on step 2 or 3

| Toxicity | Step 1 n=333 | Step 1 n=333 | Step 2 n=45 sorafenib | Step 2 n=38 placebo | Step 2 n=12 mixed | Step 3 n=35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gr 1/2 (%) | Gr 3/4 (%) | Gr 3/4 (N) | Gr 3/4 (N) | Gr 3/4 (N) | Gr 3/4 (N) | |

| Abd bloating/pain | 1/ | 2/ | ||||

| Alk phos | 22 | 1/ | 1/ | 1/ | ||

| Allergic reaction | 1/ | |||||

| Alopecia | 7 | |||||

| ALT, SGPT | 8 | |||||

| Anorexia/weight loss | 33 | 3/ | 1/ | 2/ | ||

| AST elevation | 15 | 1/ | ||||

| Back pain | 2/ | 1/ | ||||

| Bone pain | 1/ | |||||

| Chest pain | 1/ | 1/ | ||||

| Constipation | 9 | |||||

| Cough | 5 | |||||

| CNS ischemia | /1 | /1 | ||||

| Dehydration | 2/ | 1/ | ||||

| Diarrhea | 25 | 1/<1 | 2/ | 2/ | ||

| Dizziness | 1/ | 1/ | ||||

| Dry skin | 10 | |||||

| Dyspepsia | 9 | |||||

| Dyspnea | 7 | 2/1 | 1/ | 2/ | 1/ | 1/ |

| Extremity-limb. pain | 5 | 1/ | ||||

| Fatigue | 43 | 10/<1 | 3/ | 2/ | 1/ | 6/ |

| GGT | 1/ | |||||

| Hand/foot reaction | 11 | 10/ | 2/ | |||

| Headache | 7 | 2/ | ||||

| Hemoglobin | 29 | /1 | ||||

| Hemolysis | 1/ | |||||

| Hyperkalemia | 1/ | |||||

| Hypertension | 8 | 3/<1 | 1/ | 1/ | 2/ | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 1/ | |||||

| Hyponatremia | 1/ | |||||

| Hypophosphatemia | 1/ | |||||

| Hypotension | 0/ | 1/ | ||||

| Hypoxia | 1/<1 | |||||

| Infection, other | 1/ | |||||

| INR elevation | 5 | 2/ | 3/ | 1/ | ||

| Joint pain | 5 | 2/ | 1/ | |||

| L Vent sys dysf | 1/ | |||||

| Leukocytes | 11 | |||||

| Lymphopenea | 1/ | |||||

| Memory impairment | 1/ | |||||

| Mucostomatitis | 16 | 1/ | 2/ | |||

| Nausea/vomiting | 22 | 2/<1 | 1/ | 2/ | ||

| Neuropathy | 8 | 1/<1 | 1/ | |||

| Non-neuropathic generalized weakness | 1/ | |||||

| Platelets | 11 | |||||

| Pleural effusion (non-malignant) | 1/ | |||||

| Pneumonitis | 1/ | |||||

| Pruritus | 17 | 1/ | ||||

| Pulm hemorrhage | 1/ | |||||

| Rash/desquamation | 32 | 6/ | ||||

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 1/ | |||||

| Thrombosis/embolism | 1/2 | 1/ | ||||

| Vascular access, Thrombosis/embolism | 1/ |

Fifty patients died either while on treatment or within 28 days of last treatment dose for Step 1, primarily from disease progression (N =38). Eight deaths were considered treatment related: pneumonitis (two patients), bronchopulmonary hemorrhage (two patients) and one each of neutropenic fever, pneumonia, renal failure, thrombosis (PE). Of the seven deaths during Step 2 (or within 28 days of treatment), none were treatment related. Eleven deaths occurred during Step 3 (or within 28 days of last dose), of which one case (pulmonary hemorrhage) was felt to be treatment related.

Response

On Step 1, nine patients achieved a PR as the best overall response for an ORR of 3% (90% CI 1.6%=5.2%), while 117 (39%) had stable disease. In Step 2, two PRs were seen in the randomized phase of the study, one with straight sorafenib and the other with straight placebo. One PR was also reported in Step 3. Of note, all responses were seen in patients with non-squamous histology, though there was no difference in stability or progression rates by histology.

Among the 81 eligible and treated patients on Step 2, 50 patients initially received sorafenib and 31 originally received placebo (Figure 2). Although treatment was switched for 11 of the 81 during Step 2, this occurred only after two months on therapy as a 70-day drug supply was given. Consequently, these potential changes in treatment had no effect on the primary endpoint of the study; proportion of patients having stable disease or objective response two months after randomization. Analyzing patients based on their original received treatment; 27/50 (54%, 90% CI 41.5-66.2%) and 7/31 (23%, 90% CI 11.1-38.3%) of patients maintained at least stable disease two months after randomization on the sorafenib and placebo arms respectively, p=0.005.

PFS and Survival

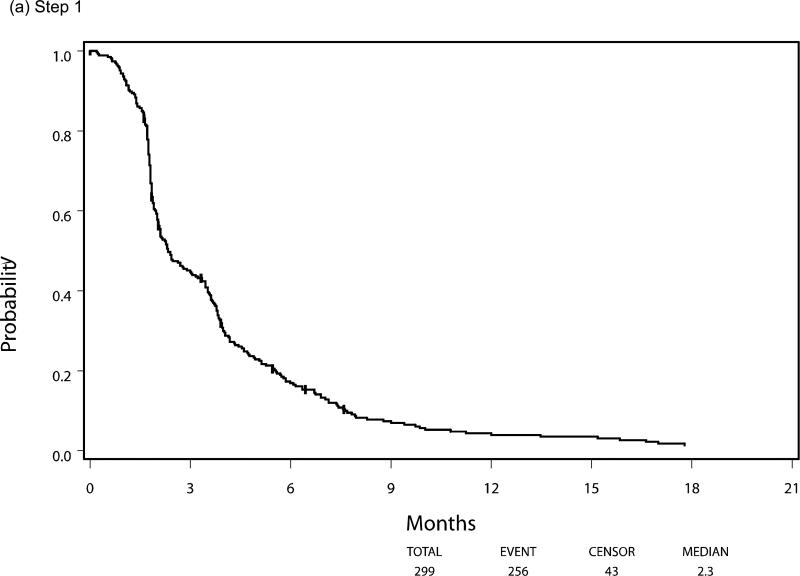

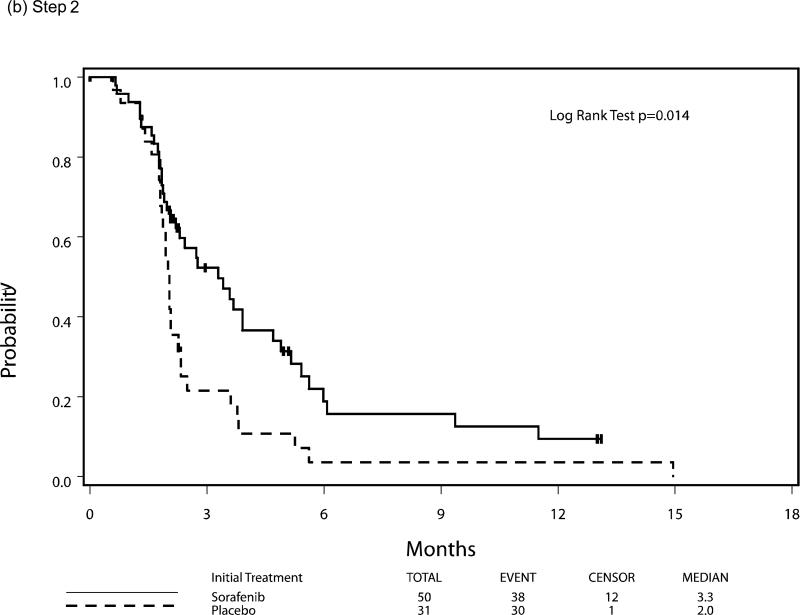

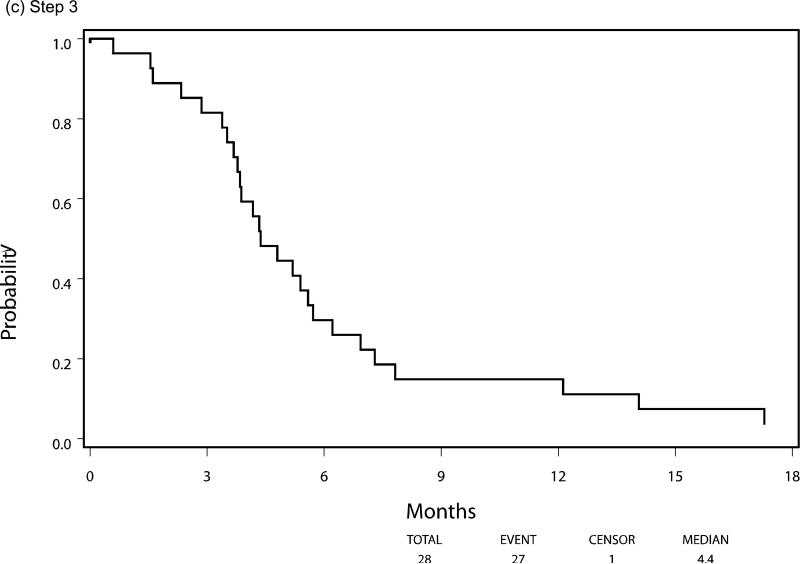

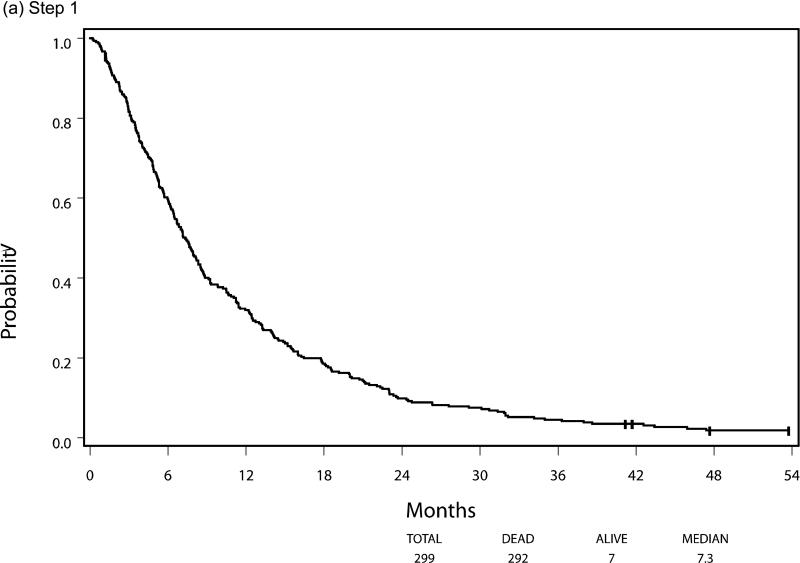

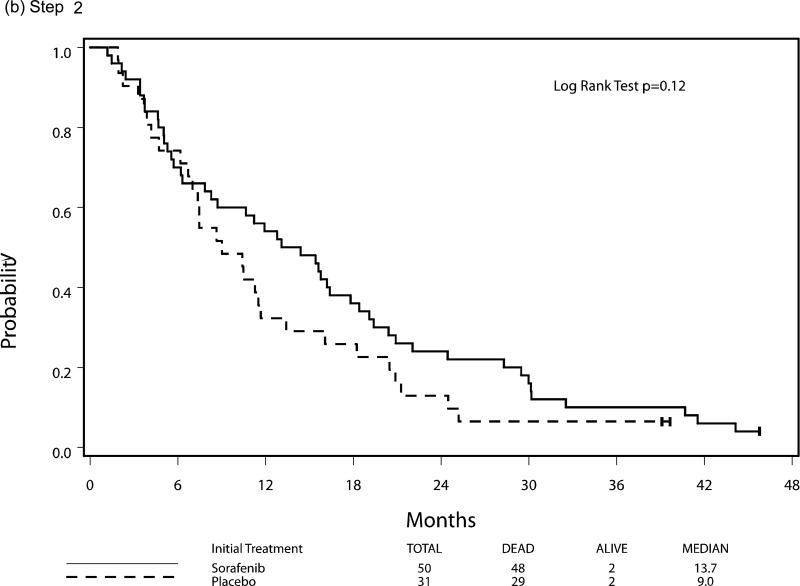

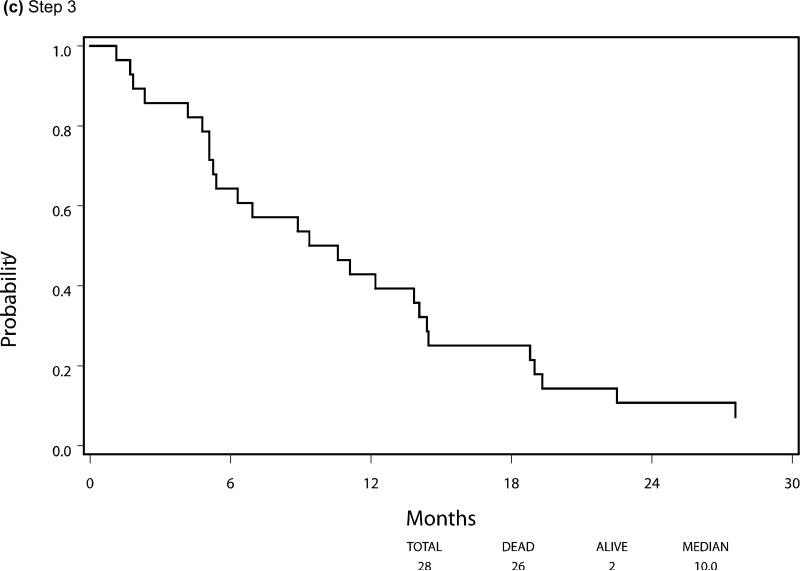

Median PFS and OS for patients who were eligible and treated on Step 1 (n=299) were 2.3 and 7.3 months respectively, with six patients still alive at the time of this analysis. Following randomization (Step 2), using the initially received treatment to group patients, the median PFS was 3.3 vs 2.0 months for the sorafenib (n=50) and placebo (n=31) arms respectively, HR 0.51 (95% CI 0.30, 0.87), p=0.014 using a stratified log-rank test. Median overall survival, from time of randomization, was 13.7 months versus 9.0 months, respectively, for the patients in the sorafenib versus placebo arms with a HR 0.67 (95% CI 0.40-1.11), p=0.117. The PFS and OS curves for patients at each step are depicted in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

Figure 3.

Progression-Free Survival by Step of Study, (a) step 1, (b) step 2, (c) step 3

Figure 4.

Overall Survival by Step of Study, (a) step 1, (b) step 2, (c) step 3

There were no differences in any Step 2 efficacy parameters (response 2 months after randomization, PFS, OS) related to therapy with either EGFR inhibitors or bevacizumab treatment prior to trial enrollment, though the study was not powered to detect such differences. Approximately half of patients on Step 2 (balanced by arm) had received prior EGFR inhibitor therapy, but the total number of patients with prior bevacizumab therapy was extremely limited (n=7 on sorafenib arm; n=3 on placebo arm), limiting interpretation of these results.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to determine the percent of patients on sorafenib versus placebo maintaining stable disease or achieving objective response after a run-in period, and met that endpoint. It is noteworthy that recent data suggests that disease control rate at 8 weeks is a good surrogate efficacy endpoint for OS in previously-treated NSCLC, supporting our choice of primary endpoint in this trial. 19, 20 Of those with stable disease after two months of run-in sorafenib on E2501, the SD/OR rate was 23% for those initially treated with placebo versus 54% for those initially treated with sorafenib, p=0.005. Additionally there was a statistically significant PFS benefit on the sorafenib arm (median PFS 3.3 vs 2.0 mo) and a strong trend for overall survival. It is important to note that these results represented only the 81 randomized eligible and treated patients, a subset of the 299 eligible and treated patients who entered on Step 1.

Although there were drug/placebo dispensing errors in Step 2 during the early phase of the study accrual, this had no effect on evaluating the primary endpoint. PFS was censored at the time of drug switching (if it occurred before disease progression) for these patients even though information was lost in this case. The OS benefit was not statistically significant for Step 2 (median OS, 13.7 vs. 9.0 months), but several factors including crossover may have attenuated this effect.

Major toxicities were noted but as expected. There was a high rate of death on trial, though mostly from disease progression, and in a heavily pretreated advanced NSCLC patient population. There were 9 deaths related to treatment out of the 333 treated (including ineligible) patients, 3 from pulmonary hemorrhage, 2 from respiratory symptoms suggestive of pneumonitis, and the rest from infection, renal toxicity or embolism; all known toxicities of the compound.21-24 We did not see any significant differences in toxicity related to histology.

Sorafenib has multiple targets of potential significance. From a clinical perspective, single agent activity of sorafenib in patients with known KRAS mutations has been reported,20, 25, 26 though we did not test for KRAS mutations in this trial.

It is clear that sorafenib cannot be combined easily with chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced stage NSCLC. A phase III trial with carboplatin/paclitaxel demonstrated no survival benefit and toxicity concerns in patients with squamous cell histology.27 In a phase III of the compound with cisplatin/gemcitabine, the combination arm failed to show an OS benefit, despite a PFS benefit.28 There have, however, been several trials with encouraging results combining sorafenib with erlotinib.21, 29, 30

Single agent activity of sorafenib has been reported in NSCLC in several smaller non-randomized studies, with a ORR of 8% and OS of 11.6 months in one previously treated cohort.26 In a first-line, window of opportunity trial, a 12% ORR (3/25) was seen.31 However, another study in previously treated patients reported a median PFS of 2.7 months and no responses, but a 59% stable disease rate.22 Accrual to a multi-national randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial with sorafenib as a single agent in previously treated patients with NSCLC was completed in late 2010 and results are eagerly awaited (NCT00863746).

Despite the unselected nature of patients on this study, this trial demonstrated a strong signal for improved disease stability, progression free survival and a trend for an overall survival benefit in patients receiving sorafenib versus placebo after a 2-month run-in period. Further trials with this compound are warranted in patients with advanced stage NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

This study was conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Robert L. Comis, M.D., Chair) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA49883, CA21076, CA49957 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Previously presented in part at the 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting and at the 2009 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Conflicts of Interest:

HAW, JWL, NHH, AMT, DPC have no conflicts to disclose

JHS has served as a paid consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 Jul-Aug;61(4):212–36. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jul 14;353(2):123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004 Oct 1;64(19):7099–109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003 Jan;3(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlomagno F, Anaganti S, Guida T, Salvatore G, Troncone G, Wilhelm SM, et al. BAY 43-9006 inhibition of oncogenic RET mutants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Mar 1;98(5):326–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm S, Chien DS. BAY 43-9006: preclinical data. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(25):2255–7. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons JF, Wilhelm S, Hibner B, Bollag G. Discovery of a novel Raf kinase inhibitor. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001 Sep;8(3):219–25. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark JW, Eder JP, Ryan D, Lathia C, Lenz HJ. Safety and pharmacokinetics of the dual action Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, BAY 43-9006, in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Aug 1;11(15):5472–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, Schleucher N, Korfee S, Tewes M, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Feb 10;23(5):965–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strumberg D, Clark JW, Awada A, Moore MJ, Richly H, Hendlisz A, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary antitumor activity of sorafenib: a review of four phase I trials in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. Oncologist. 2007 Apr;12(4):426–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-4-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 11;356(2):125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratain MJ, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Flaherty KT, Kaye SB, Rosner GL, et al. Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jun 1;24(16):2505–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 10;24(26):4293–300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopec JA, Abrahamowicz M, Esdaile JM. Randomized discontinuation trials: utility and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993 Sep;46(9):959–71. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90163-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riely GJ, Kris MG, Rosenbaum D, Marks J, Li A, Chitale DA, et al. Frequency and distinctive spectrum of KRAS mutations in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Sep 15;14(18):5731–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adjei AA. Blocking oncogenic Ras signaling for cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001 Jul 18;93(14):1062–74. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brose MS, Volpe P, Feldman M, Kumar M, Rishi I, Gerrero R, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002 Dec 1;62(23):6997–7000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, et al. Paclitaxel-Carboplatin Alone or With Bevacizumab for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006 Dec 14;355(24):2542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto N, Nishiwaki Y, Negoro S, Jiang H, Itoh Y, Saijo N, et al. Disease control as a predictor of survival with gefitinib and docetaxel in a phase III study (V-15-32) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2010 Jul;5(7):1042–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181da36db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR, Jr., Tsao A, et al. The BATTLE Trial: Personalized Therapy for Lung Cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2011;1:44–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lind JS, Dingemans AM, Groen HJ, Thunnissen FB, Bekers O, Heideman DA, et al. A multicenter phase II study of erlotinib and sorafenib in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Jun 1;16(11):3078–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumenschein GR, Jr., Gatzemeier U, Fossella F, Stewart DJ, Cupit L, Cihon F, et al. Phase II, multicenter, uncontrolled trial of single-agent sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Sep 10;27(26):4274–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myung HJ, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Kim HS, Jang JH, Yoon HI, et al. Sorafenib-induced interstitial pneumonitis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Gut Liver. 2010 Dec;4(4):543–6. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.4.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ide S, Soda H, Hakariya T, Takemoto S, Ishimoto H, Tomari S, et al. Interstitial pneumonia probably associated with sorafenib treatment: An alert of an adverse event. Lung Cancer. 2010 Feb;67(2):248–50. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smit EF, Dingemans AM, Thunnissen FB, Hochstenbach MM, van Suylen RJ, Postmus PE. Sorafenib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer that harbor K-ras mutations: a brief report. J Thorac Oncol. 2010 May;5(5):719–20. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d86ebf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly RJ, Rajan A, Force J, Lopez-Chavez A, Keen C, Cao L, et al. Evaluation of KRAS mutations, angiogenic biomarkers, and DCE-MRI in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Mar 1;17(5):1190–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scagliotti G, Novello S, von Pawel J, Reck M, Pereira JR, Thomas M, et al. Phase III study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Apr 10;28(11):1835–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatzemeier U, Eisen T, Santoro A, Paz-Ares L, Bonnouna J, Liao M, et al. Sorafenib (S) + Gemcitabine/Cisplatin (GC) vs GC Alone in the First-Line Treatment of Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC); Phase III NSCLC Research Experience Utilizing Sorafenib (NEXUS) Trial. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(Suppl 8):viii7. (abstr LBA 16) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spigel DR, Burris HA, 3rd, Greco FA, Shipley DL, Friedman EK, Waterhouse DM, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase II Trial of Sorafenib and Erlotinib or Erlotinib Alone in Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 20;29(18):2582–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gridelli C, Morgillo F, Favaretto A, de Marinis F, Chella A, Cerea G, et al. Sorafenib in combination with erlotinib or with gemcitabine in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2011 Jul;22(7):1528–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dy GK, Hillman SL, Rowland KM, Jr., Molina JR, Steen PD, Wender DB, et al. A front-line window of opportunity phase 2 study of sorafenib in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study N0326. Cancer. 2010 Dec 15;116(24):5686–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]