Abstract

Studies were done on analysis of biological processes in the same high expression (fold change ≥2) activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion gene ontology (GO) network of human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection). Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion network consisted of anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, cell adhesion, cell differentiation, cell-cell signaling, G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, intracellular transport, metabolism, phosphoinositide-mediated signaling, positive regulation of transcription, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, regulation of transcription, signal transduction, transcription, and transport in HCC. We proposed activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network. Our hypothesis was verified by the different activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, or the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC. Activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network included BUB1B, GNG10, PTHR2, GNAZ, RFC4, UBE2C, NRXN3, BAP1, PVRL2, TROAP, and VCAN in HCC from GEO dataset using gene regulatory network inference method and our programming.

1. Introduction

PTHLH is one of our identified significant high expression (fold change ≥2) genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with low expression no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection) from GEO data set GSE10140-10141 [1].

Study of PTHLH is presented in some papers, such as Mouse pthlh gene-specific expression profiles distinguish among functional allelic variants in transfected human cancer cells [2]; parathyroid hormone-like protein alternative messenger RNA splicing pathways in human cancer cell lines [3]; parathyroid hormone-like peptide in pancreatic endocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma associated with hypercalcemia [4]; parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-like peptide bioactivity in situ biochemistry [5]; parathyroid hormone-like protein polypeptides immunological identification and distribution in normal and malignant tissues [6]; dysregulation of parathyroid hormone-like peptide expression and secretion in a keratinocyte model of tumor progression [7]; all major lung cancer cell types produce parathyroid hormone-like protein [8]; parathyroid hormone-like peptide in normal and neoplastic mesothelial cells [9]. Yet the high expression activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion mechanism in HCC is not clear and remains to be elucidated.

In this study, biological processes and occurrence numbers of the same activated high expression (fold change ≥2) PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC were identified and computed compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection), the different compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC, respectively. Simultaneous occurrence of biological processes was identified between the same activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC (compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues) and the different (compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues), or the same (compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC) for putting forward hypothesis of activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network. Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network and numbers in HCC were extracted and computed from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues. PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion molecular relationship in HCC was identified including different molecules but same GO term and same molecule but different GO terms from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues.

2. Materials and Methods

Microarray 6,144 genes were used for analyzing activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion mechanism of HCC based on GEO data set GSE10140-10141 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10140, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE10141). The raw microarray data was preprocessed by log base 2.

225 significant high expression (fold change ≥2) molecules in HCC compared with no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection) were identified using significant analysis of microarrays (SAM) (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/) [10]. We selected two classes paired and minimum fold change ≥2 under the false-discovery rate was 0%.

Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion mechanism of HCC was analyzed by using Molecule Annotation System, MAS (CapitalBio Corporation, Beijing, China; http://bioinfo.capitalbio.com/mas3/). The primary databases of MAS integrated various well-known biological resources, such as Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org/), KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), BioCarta (http://www.biocarta.com/), GenMapp (http://www.genmapp.org/), HPRD (http://www.hprd.org/), MINT (http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/mint/Welcome.do), BIND (http://www.blueprint.org/), Intact (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/), UniGene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/unigene), OMIM (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM), and disease (http://bioinfo.capitalbio.com/mas3/).

Biological processes and occurrence numbers of the same activated high expression (fold change ≥2) PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC were identified and computed compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection), the different compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC by our programming, respectively.

Simultaneous occurrence of biological processes was identified between the same activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC (compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues) and the different (compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues), or the same (compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC) for putting forward hypothesis of activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network by our programming, respectively.

Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network and numbers in HCC were extracted and computed from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues by our programming, respectively.

At last, PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion molecular relationship in HCC was identified including different molecules but same GO term and same molecule but different GO terms from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and constructed network by GRNInfer [11] and our articles [12–25] and illustrated by GVedit tool.

3. Results

Biological processes and occurrence numbers of the same activated high expression (fold change ≥2) PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC were identified and computed compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection), the different compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC, respectively.

The same biological processes of activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC included anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, cell adhesion, cell differentiation, cell-cell signaling, endothelial cell migration, G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, G-protein signaling, intracellular transport, metabolism, phosphoinositide-mediated signaling, positive regulation of transcription, protein amino acid phosphorylation, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, regulation of transcription, signal transduction, transcription, and transport compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues.

The different biological processes of activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC contained integrin-mediated signaling pathway, intracellular transport, microtubule cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis, regulation of cell growth, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues.

The same biological processes of activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC included anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, cell adhesion, cell differentiation, cell-cell signaling, DNA repair, G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, integrin-mediated signaling pathway, metabolism, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism, oxidation reduction, phosphoinositide-mediated signaling, positive regulation of transcription, protein modification, proteolysis, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, regulation of transcription, signal transduction, and transcription, transport compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

(a) Biological processes and occurrence numbers of the same activated high expression (fold change ≥2) PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection), (b) the different compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and (c) the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC by our programming.

| (a) Biological process and occurrence number of GO term | |

|---|---|

| Anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism | 5 |

| Cell adhesion | 8 |

| Cell differentiation | 2 |

| Cell-cell signaling | 5 |

| Endothelial cell migration | 2 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway | 4 |

| G-protein signaling | 2 |

| Intracellular transport | 2 |

| metabolism | 4 |

| Phosphoinositide-mediated signaling | 4 |

| Positive regulation of transcription | 3 |

| Protein amino acid phosphorylation | 8 |

| Regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity | 8 |

| Regulation of transcription | 8 |

| Signal transduction | 10 |

| Transcription | 8 |

| Transport | 2 |

|

| |

| (b) Biological process and occurrence number of GO term | |

|

| |

| Integrin-mediated signaling pathway | 2 |

| Intracellular transport | 2 |

| Microtubule cytoskeleton organization and biogenesis | 2 |

| Regulation of cell growth | 2 |

| Regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity | 8 |

|

| |

| (c) Biological process and occurrence number of GO term | |

|

| |

| Anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism | 5 |

| Cell adhesion | 8 |

| Cell differentiation | 2 |

| Cell-cell signaling | 5 |

| DNA repair | 2 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway | 4 |

| Integrin-mediated signaling pathway | 2 |

| Metabolism | 4 |

| Nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism | 2 |

| Oxidation reduction | 5 |

| Phosphoinositide-mediated signaling | 4 |

| Positive regulation of transcription | 3 |

| Protein modification | 2 |

| Proteolysis | 5 |

| Regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity | 8 |

| Regulation of transcription | 8 |

| Signal transduction | 10 |

| Transcription | 8 |

| Transport | 2 |

Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network and numbers in HCC were extracted and computed from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues. Our result showed that PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network consisted of BUB1B, GNG10, PTHR2, GNAZ, RFC4, UBE2C, NRXN3, BAP1, PVRL2, TROAP, VCAN, CCNA2, CDC6, CDKN2C, and ENAH in HCC, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network and numbers in HCC from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues by our programming.

| Molecular name and number | |

|---|---|

| BUB1B, GNG10, PTHR2, GNAZ, RFC4, UBE2C, NRXN3, BAP1, PVRL2, TROAP, VCAN, CCNA2, CDC6, CDKN2C, ENAH | 15 |

4. Discussion

Our aim is to study novel high expression-activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion mechanism in HCC. In this study, biological processes and occurrence numbers of the same activated high expression (fold change ≥2) PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network in HCC were identified and computed compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection), the different compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, and the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC, respectively (Table 1).

Simultaneous occurrence of biological processes was identified between the same activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC (compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues) and the different (compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues), or the same (compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC) for putting forward hypothesis of activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network, respectively.

Simultaneous occurrence of biological processes consisted of intracellular transport, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity between the same activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC (compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues) and the different (compared with the corresponding inhibited PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues).

Simultaneous occurrence of biological processes included anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, cell adhesion, cell differentiation, cell-cell signaling, G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, metabolism, phosphoinositide-mediated signaling, positive regulation of transcription, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, regulation of transcription, signal transduction, transcription, transport between the same activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC (compared with the corresponding activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues), and the same (compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC).

The studies of phosphoinositide with adhesion are presented as follows. Phosphoinositide lipid phosphatase SHIP1 and PTEN coordinate to regulate cell migration and adhesion [26], TAPP2 links phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling to B-cell adhesion through interaction with the cytoskeletal protein utrophin: expression of a novel cell adhesion-promoting complex in B-cell leukemia [27], neuregulin-1 regulates cell adhesion via an ErbB2/phosphoinositide-3 kinase/Akt-dependent pathway: potential implications for schizophrenia and cancer [28], stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple focal adhesion proteins and induces migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells: roles of phosphoinositide-3 kinase and protein kinase C [29], and functional association of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase in human neutrophils [30]. Therefore, we proposed activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network in HCC.

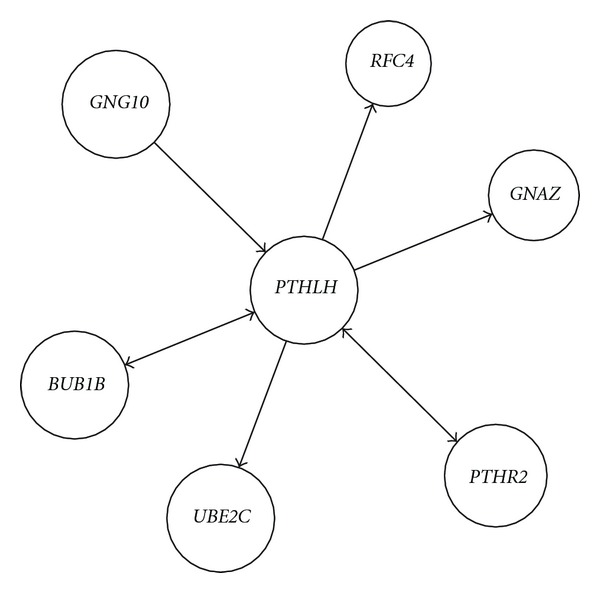

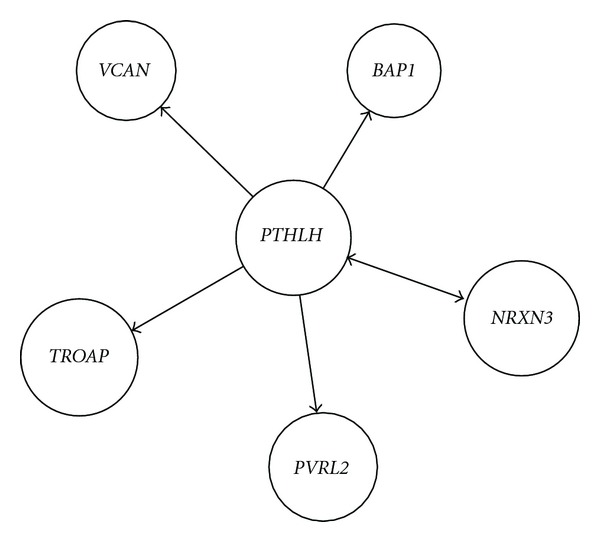

Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion molecular network and numbers in HCC were extracted and computed from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (Table 2). PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion molecular relationship in HCC was identified including different molecules but same GO term and same molecule but different GO terms from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues. Activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal network included BUB1B, GNG10, PTHR2, GNAZ, PTHR2, BUB1B, RFC4, and UBE2C and activated PTHLH feedback cell adhesion network NRXN3, BAP1, NRXN3, PVRL2, TROAP, and VCAN in HCC, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal network construction including different molecules but same GO term and same molecule but different GO terms in HCC from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues by GRNInfer and our programming.

Figure 2.

Activated PTHLH feedback cell adhesion network construction including different molecules but same GO term and same molecule but different GO terms in HCC from the same activated PTHLH GO-molecular network of HCC compared with the corresponding activated GO-molecular network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues by GRNInfer and our programming.

In summary, studies were done on analysis of biological processes in the same high expression (fold change ≥2) activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC compared with the corresponding low expression activated GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues (HBV or HCV infection). Activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion network consisted of anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, cell adhesion, cell differentiation, cell-cell signaling, G-protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, intracellular transport, metabolism, phosphoinositide-mediated signaling, positive regulation of transcription, regulation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity, regulation of transcription, signal transduction, transcription, and transport in HCC. We proposed activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network. Our hypothesis was verified by the different activated PTHLH feedback-mediated cell adhesion GO network of HCC compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues, or the same compared with the corresponding inhibited GO network of HCC. Activated PTHLH coupling feedback phosphoinositide to G-protein receptor signal-induced cell adhesion network included BUB1B, GNG10, PTHR2, GNAZ, RFC4, UBE2C, NRXN3, BAP1, PVRL2, TROAP, and VCAN in HCC from GEO data set using gene regulatory network inference method and our programming.

Authors' Contribution

Equal contribution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 61171114), the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars for Scientific research Foundation of State Education Ministry, Significant Science and Technology Project for New Transgenic Biological Species (2009ZX08012-001B), Automatical Scientific Planning of Tsinghua University (20111081023 and 20111081010), and State Key Lab of Pattern Recognition Open Foundation.

References

- 1.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(19):1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gianni-Barrera R, Gariboldi M, De Cecco L, Manenti G, Dragani TA. Specific gene expression profiles distinguish among functional allelic variants of the mouse Pthlh gene in transfected human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25(32):4501–4504. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt DW, Wachsman W, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-like protein: alternative messenger RNA splicing pathways in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Research. 1994;54(3):850–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miraliakbari BA, Asa SL, Boudreau SF. Parathyroid hormone-like peptide in pancreatic endocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma associated with hypercalcemia. Human Pathology. 1992;23(8):884–887. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90399-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loveridge N, Dean V, Goltzman D, Hendy GN. Bioactivity of parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-like peptide: agonist and antagonist activities of amino-terminal fragments as assessed by the cytochemical bioassay and in situ biochemistry. Endocrinology. 1991;128(4):1938–1946. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer S, Reynolds FH, Castillo M, Valenzuela DM, Thorikay M, Sorvillo JM. Immunological identification and distribution of parathyroid hormone-like protein polypeptides in normal and malignant tissues. Endocrinology. 1991;128(4):1927–1937. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson J, Sebag M, Rhim J, Goltzman D, Kremer R. Dysregulation of parathyroid hormone-like peptide expression and secretion in a keratinocyte model of tumor progression. Cancer Research. 1991;51(24):6521–6528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt DW, Burton DW, Gazdar AF, Oie HE, Deftos LJ. All major lung cancer cell types produce parathyroid hormone-like protein: heterogeneity assessed by high performance liquid chromatography. Endocrinology. 1991;129(5):2466–2470. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAuley P, Asa SL, Chiu B, Henderson J, Goltzman D, Drucker DJ. Parathyroid hormone-like peptide in normal and neoplastic mesothelial cells. Cancer. 1990;66(9):1975–1979. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901101)66:9<1975::aid-cncr2820660921>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 2002;64(3):479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Joshi T, Zhang XS, Xu D, Chen L. Inferring gene regulatory networks from multiple microarray datasets. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(19):2413–2420. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Sun Y, Jiang M, Zheng X. Integrative decomposition procedure and kappa statistics for the distinguished single molecular network construction and analysis. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2009;2009:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2009/726728.726728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Sun Y, Jiang M, Zhang S, Wolfl S. FOS proliferating network construction in early colorectal cancer (CRC) based on integrative significant function cluster and inferring analysis. Cancer Investigation. 2009;27(8):816–824. doi: 10.1080/07357900802672753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Sun L, Huang J, Jiang M. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 (CDKN3) novel cell cycle computational network between human non-malignancy associated hepatitis/cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) transformation. Cell Proliferation. 2011;44(3):291–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2011.00752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M, Zheng X. AFP computational secreted network construction and analysis between human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic liver tissues. Tumour Biology. 2010;31(5):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s13277-010-0050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M, Sun L. MYBPC1 computational phosphoprotein network construction and analysis between frontal cortex of HIV encephalitis (HIVE) and HIVE-control patients. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2011;31(2):233–241. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M, Sun L. Survivin (BIRC5) cell cycle computational network in human no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma transformation. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2011;112(5):1286–1294. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M, Lin H. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 (STAT2) metabolism coupling postmitotic outgrowth to visual and sound perception network in human left cerebrum by biocomputation. Journal of molecular neuroscience. 2012;47(3):649–58. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M. RRM2 computational phosphoprotein network construction and analysis between no-tumor hepatitis/cirrhotic liver tissues and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2010;26(3):303–310. doi: 10.1159/000320553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Huang J, Jiang M. CREB5 computational regulation network construction and analysis between frontal cortex of HIV encephalitis (HIVE) and HIVE-control patients. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2011;60(3):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s12013-010-9140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Wang L, Liu L. Integrative decomposition procedure and Kappa statistics set up ATF2 ion binding module in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) Frontiers of Electrical and Electronic Engineering in China. 2008;3(4):381–387. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Y, Wang L, Jiang M, Huang J, Liu Z, Wolfl S. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 upstream invasive network construction and analysis of lung adenocarcinoma compared with human normal adjacent tissues by integrative biocomputation. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2010;56(2):59–71. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun L, Wang L, Jiang M, Huang J, Lin H. Glycogen debranching enzyme 6 (AGL), enolase 1 (ENOSF1), ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase 2 (ENPP2_1), glutathione S-transferase 3 (GSTM3_3) and mannosidase (MAN2B2) metabolism computational network analysis between chimpanzee and human left cerebrum. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2011;61(3):493–505. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang JX, Wang L, Jiang MH. TNFRSF11B computational development network construction and analysis between frontal cortex of HIV encephalitis (HIVE) and HIVE-control patients. Journal of Inflammation. 2010;7, article 50 doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Wang L, Jiang M, Zheng X. Interferon α-inducible protein 27 computational network construction and comparison between the frontal cortex of HIV encephalitis (HIVE) and HIVE-control patients. Open Genomics Journal. 2010;3(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mondal S, Subramanian KK, Sakai J, Bajrami B, Luo HR. Phosphoinositide lipid phosphatase SHIP1 and PTEN coordinate to regulate cell migration and adhesion. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23(7):1219–1230. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costantini JL, Cheung SMS, Hou S, et al. TAPP2 links phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling to B-cell adhesion through interaction with the cytoskeletal protein utrophin: expression of a novel cell adhesion-promoting complex in B-cell leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(21):4703–4712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanakry CG, Li Z, Nakai Y, Sei Y, Weinberger DR. Neuregulin-1 regulates cell adhesion via an ErbB2/phosphoinositide-3 kinase/akt-dependent pathway: potential implications for schizoprenia and cancer. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001369.e1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JF, Park IW, Groopman JE. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple focal adhesion proteins and induces migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells: roles of phosphoinositide-3 kinase and protein kinase C. Blood. 2000;95(8):2505–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pellegatta F, Chierchia SL, Zocchi MR. Functional association of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase in human neutrophils. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(43):27768–27771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]