Abstract

Medical education has been and continues to be a priority in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia since the establishment of the first medical school more than 30 years ago. As the kingdom moves into the new millennium through its 100th birthday, several issues pertaining to medical education are noted. These include selection and admission criteria to medical schools, suitability concerns, and the need for reform of the current undergraduate curriculum as well as allocation and utilization of available resources. The postgraduate medical training programs, particularly the university-based, need re-evaluation, and definition of their future role in graduate medical education. Medical educators must make sure that research in medical education should not only survive but also thrive. In this article, some suggestions for Saudi medical education in n the new millennium are put forth.

Keywords: Medical Education, Curriculum, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

Higher education has been and continues to be one of the most important priorities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for the past 100 years. This has led to the establishment of more than 10 universities nationwide. As a result, significant development has occurred in the natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities. Particular attention was given to medicine with the establishment of 6 medical schools, the most recent of which has been established in 1999. There exist current plans to established more medical schools. For every college there is a set goal that it tries to attain through a carefully articulated curriculum. These colleges wanted to produce physicians who are competent in their profession, aware and able to respond to the societies’ health need and able to pursue graduate education both nationally and internationally. Most of these objectives have been achieved. However, experience has accumulated in medical education in the kingdom since the establishment of the first college more than 30 years ago (1969). Some concerns regarding medical education do exist.1,2 Coupled with the significant scientific, economic and social changes over the past decades a closer look at the current medical education is warranted to identify areas of concern, stimulate discussion and consensus consolidation among medical educators in our society.

THE PRE-BACCALAUREATE

Immediately after successfully leaving high school, prospective candidates join the medical school. This makes the high school curriculum a platform from which candidates could join career in medicine. It has been noted that one of the most formidable obstacles to such candidates is the relatively poor command of the English language. Specially as it relates to health care issues as well as an awareness of the needed tools to search for information, which will better, prepare them for the medical career. Perhaps this could be remedied by specially designed pre-medical school courses, which would concentrate on the necessary acquisition of English language skills at either the second semester of the high school or in the summer prior to joining the medical school. These courses could also be utilized to improve communication skills and the ability to search and retrieve information.

Another more radical solution is to change the medium of education from English to Arabic in the field of medicine. Such undertaking requires paramount efforts and resources, which are not the scope of this article.

MEDICAL SCHOOL ADMISSION / SELECTION

Admission policies vary widely within the Kingdom. This is not particularly unique because such policies do vary at times widely throughout the world and indeed within individual countries.3 With the increasing number of applicants to medical schools coupled with limited resources, setting pre-defined criteria for admission to medical schools is needed. Traditionally in the kingdom reliance falls upon academic criteria for admission wherein the top 10% of high school leavers are allowed to enter the competition to join the medical school. Some colleges in the Kingdom may depend solely on the academic score at the end of high school. Others formulated a written admission test coupled with an interview. The first method relying purely on academic performance has shown that high school grades do not predict performance beyond the traditional pre-clinical years.4 The second group of admission methods frequently uses non-structured interviews, which frequently has been blamed for lack of objectivity and group consensus. The admission criteria and process being used in the medical schools is far from being perfect. Problems of increasing number of candidates, restricted number of slots and limited resources are major constraining factors. Admission criteria should be tailored within each medical school specifically to the available resources.

THE CURRENT UNDERGRADUATE CURRICULUM CONCERNS

Medical education in the Kingdom like many parts of the world is based on a mixture of the Flexenarian concept applied in a British style. The main features of the flexenarian concept include a clear separation between the basic and the clinical sciences wherein the basic sciences are taught first followed by the clinical sciences. Such a system depends heavily on didactic sessions with emphasis on lectures as the main teaching method and source of information. These were often related to independent courses whose objectives were set and made more relevant to individual departments, disciplines or specialties than the real needs of the community, which the medical graduate will eventually serve. This has led to absence of mechanisms where a rational and integrated mechanism for ensuring a broad general education in medicine focusing on its relevance to the community needs as well as over presentation of some subjects and the presence of relatively non-relevant subjects. In addition, the response to burgeoning knowledge in medicine have added more and more into the curriculum leading to overload so significantly that it has impeded the student's progress in their medical program. Such curriculum overcrowding has prevented the introduction of essential subjects that particularly address specific scientific, ethical or communication issues.

Despite the WHO Alma-Ata declaration in 1978 “Health for all initiative by the year 2000” where a physician should respond to community health care needs.5 There has been minimal community-based education in the kingdom. This has traditionally been given during the Family and Community rotation for a limited/insufficient period.

Frequent examinations, which are carried out in traditional mode, have been and continue to be formidable obstacles to thorough learning. This is clearly seen in Saudi Medical Schools where each course has its own end-of-course examination. This means that the medical student will undergo a minimum of 51 end-of-course examinations, (24 in basic sciences and 27 in clinical sciences). Simple Arithmetic calculation will show that the medical student will undergo, upon completion of medical courses, a minimum of one examination every 4.2 weeks. This is hardly conducive to the development and promotion of the capacity for self-education, critical thinking, and evaluation of the evidence. Furthermore, the reliability, validity, and stress effect of these examination on students are seldom studied objectively. This is further compounded by the absence of a national examination that assesses the medical students at certain critical levels at the end of the basic sciences years and the time for graduation. This has led to some heterogeneity in the performance level of various graduates from various medical schools within the Kingdom.

To be able to admit such large numbers of students, Saudi Medical Schools need to diversify and widen undergraduate teaching programs to include adequately structured, equipped and staffed non-university hospitals and centers. A national accreditation body identified for undergraduate medical education should appropriately evaluate these non-university hospitals. Such a national organization should develop its own guidelines, standards and procedure for accreditation of the various hospitals selected for the specific purpose of undergraduate medical education.6 This will utilize public and private resources rationally and may cost effectively produce the best possible health care services as well as expand the curriculum beyond the individual university hospital focus.

One of the most important aspects of the educational cycle is the educator. Medical students frequently learn from other senior medical students or residents but more importantly from faculty role models. The Saudi Medical Schools has been lucky to have had good educators characterized by immense knowledge of their respective subjects, enthusiasm for teaching and high moral standards to act as living role models for medical students. However, the emphasis of the promotion guidelines of faculty members on biomedical research rather than excellence in teaching has lead to a situation wherein faculty members spend more of their efforts in research activities. More recently with the implementation of privatization of faculty members, on part-time basis, further decline in learner-facilitator (student teacher) interaction is expected with probably an over-all negative effect on medical students’ education.

THE REFORM IDEA

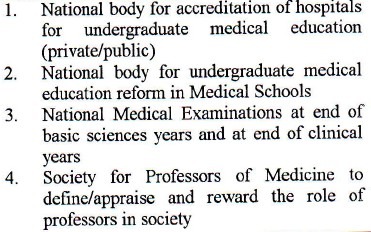

Reform is derived from the combination of the Latin (re-) prefix signifying back or again and the word (form) from the Latin word forma which means the characteristics of structural entity generally determined by its shape, size or other external or visible features. However, in medical education reform signifies centralization of the curriculum, integration of various basic and clinical disciplines with the emphasis on relevance, and creation of new courses.7,8 Other segments of curriculum reform may include holistic approach to curriculum design, community based medical education, improving the educational experience of students, equality and cost effectiveness. Despite the plethora of literature supporting the adoption of these ideas, most of medical schools in the world continue the traditional approach of the flexenerian system. This had created a situation where reform has been proposed and supported by both the educators and administrators without actual change. The absence of a national body that deals with accreditation of medical schools in the kingdom has lead to paucity of curriculum reviews and is left to the individual medical schools themselves. Regular reviews of undergraduate curricula by a national body with defined set objectives and specific criteria for curriculum reform may help minimize the heterogeneity in the curriculum of the various medical schools and the variability in the level of their respective graduates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Suggestions for Saudi Medical Education in the new Millennium include the creation of:

POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION ISSUES

In We early 1980s, Saudi universities launched multi-faceted plan to establish sound postgraduate studies in medicine. Initially, international bodies were encouraged to carry out the examinations in the kingdom for trainees in Saudi hospitals. The Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and Great Britain were leaders in this regard. In 1982, the Arab health ministers met in Kuwait and established the Pan-Arab Board for medical specialties. One of the early academic health centers accredited in the kingdom was King Fahd Hospital of the University, Al-Khobar, in 1983 for training in Family and Community Medicine. Through hard work and perseverance, university fellowship programs were established in many specialties in most Saudi Medical schools. These programs attracted many graduates from various regions of the kingdom who have successfully completed the programs and have gone to fill key positions in the kingdom. In 1992, the Saudi Council for Health Specialties was established. The enthusiastic and ambitious leadership has formulated the accreditation standards and subsequently accredited various hospitals in the kingdom for training in the major specialties and in some sub-specialties. However, there exists problems, which may be considered major stumbling blocks and need to be addressed in a thorough and orderly manner. These include the limited number of slots for training compared to health care needs for the kingdom with an ever-growing population at a rate of 3.5%. The relative lack of ultra-specialties that are needed from both the service and academic point of views including genetics, immunology, radiation oncology, transplant surgery and various pediatrics subspecialties (e.g., nephrology, neurology, etc). Furthermore, research activities carried out by the trainees are almost non-existing, and when done it is usually descriptive with minimal molecular aspects. This probably reflects the minimum availability of the needed infrastructure and resources to carry out such research. It is envisioned that the Saudi Council for Health Specialties will eventually shoulder most of the existing university programs. Such an enormous task will require appropriate resources. On the other hand, universities need to re-evaluate, appraise and define their future role in graduate medical education in the Kingdom. Such roles should be discussed nationally at various levels to establish a consensus on the future plan that addresses future health care needs of the community.

MEDICAL EDUCATION RESEARCH

Medical education research is vital for the continuing development and enhancement of the educational experience of both the learners and the facilitators.9 Such research should include various aspects of the educational cycle including: curriculum design and structure, curriculum implementation, student evaluation. Other research areas may include extrinsic and intrinsic factors that may influence either the learner or the facilitator in the educational cycle as well as various forms of the curriculum as they relate to health care system in the Kingdom.10 Authorities need to place these research themes as a priority with appropriate financial support.

The monumental process of change in various aspects of medical education starts by creating a dialogue and discussions between the experts in medical education to forge a consensus of various aspects of medical education. Such a consensus should be based on community needs, available resources and current achieved international standards. This perhaps could be debated nationally utilizing conferences, workshops and journals with the view towards creating the right environment for change. Once consensus is achieved and support is granted provision of resources fundamentally needed for reform should be used in cost-effective manner.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Gindan YM, Al-Sulaiman AA. Undergraduate Curriculum Reform in Saudi Medical Schools, Needed or Not? Saudi Medical Journal. 1998;19:229–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox RC. Time to Heal Medical Education? Academic Medicine. 1999;74(10):1072–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood DF. Medical School Selection – Fair or Unfair Medical Education. 1999;33:399–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.0432a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson PH, Winder B, Briggs K, Tydeman C. Grade Predictions for School-Leaving Examinations: Do they predict anything? Medical Education. 1998;32:294–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AWHO Global Strategy for Changing Medical Education and Medical Practice for Health for All. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. World Health Organization Doctors for Health. [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Standards in Medical Education: Assessment and Accreditation of Medical Schools’-educational programmes. A WFME position paper. Medical Education. 1998;32:548–549. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassenbaun DG, Cutler ER, Eagler RH. The Influence of Accreditation on Educational Change in U.S. Medical Schools. Academic Medicine. 1999;72(12):1127–33. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199712000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Gindan YM, Al-Sulaiman AA, Al-Faraidy AA. Undergraduate Curriculum Reform in Saudi Medical Schools: Which Direction to go? Saudi Medical Journal. 2000;21:324–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson MB. Reports of New approaches in Medical Education. 1999;74: 261-8. Academic Medicine. 1999;74:261–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenlick MR. Educating Physicians for the Twenty-first Century. Academic Medicine. 1995;70:179–85. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]