Abstract

Acute tissue injury is often considered in the context of a wound. The host response to wounding is an orchestrated series of events, the fundamentals of which are preserved across all multicellular organisms. In the human lung, there are a myriad of causes of injury, but only a limited number of consequences: complete resolution, persistent and/or overwhelming inflammation, a combination of resolution/remodelling with fibrosis or progressive fibrosis. In all cases where complete resolution does not occur, there is the potential for significant ongoing morbidity and ultimately death through respiratory failure. In this review, we consider the elements of injury, resolution and repair as they occur in the lung. We specifically focus on the role of the macrophage, long considered to have a pivotal role in regulating the host response to injury and tissue repair.

Keywords: healing, lung, macrophages

Introduction

The terms ‘healing’, ‘repair’, ‘remodelling’ and ‘fibrosis’ are sometimes used in different contexts. Herein, we consider ‘healing’ and ‘repair’ to be synonymous and define healing as the process of resolution or attenuation of inflammation, which encompasses both remodelling and fibrosis. Remodelling implies new tissue formation, and this is either functional with the capacity for restoration of normal tissue architecture and physiology or pathological which leads to fibrosis with loss of tissue architecture and organ dysfunction. In some circumstances, functional repair may occur even after fibrosis has been initiated as collagen may then be reabsorbed and a degree of tissue architecture restored (Table 1). In epithelial tissues with a basement membrane such as the lungs, the critical division between functional and pathological repair may be determined by the extent of basement membrane damage (Wallace et al. 2007; Strieter 2008).

Table 1.

Potential consequences of different types of lung diseases after injury or wounding

| Lung disease | Complete resolution | Persistent or overwhelming inflammation | Resolution with remodelling and fibrosis | Progressive fibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARDS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Occasionally |

| Asthma | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cystic fibrosis | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Bacterial pneumonia | Yes | Yes | Occasionally | No |

| Tuberculosis | Yes | Occasionally | Yes | Occasionally |

| Pulmonary Sarcoidosis | Yes | Occasionally | Yes | Occasionally |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pneumoconiosis e.g. silicosis, asbestosis | No | Rarely | Yes | Yes |

| Pulmonary vasculitis e.g. Wegener's granulomatosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Occasionally |

The generic phases of wound healing: do they occur in the lung?

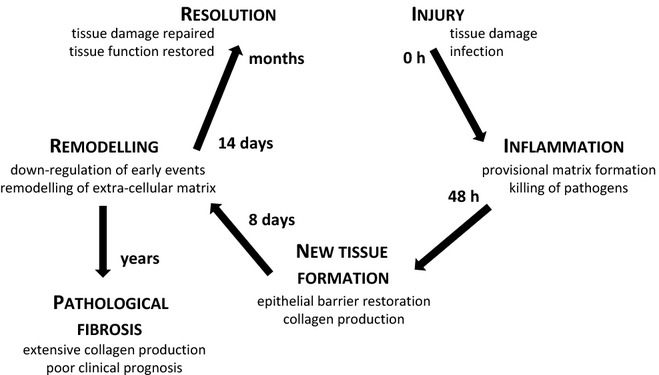

The fundamental mechanisms of tissue repair following injury are similar in all multicellular organisms that have a circulation. In mammals, the classic wound repair events have perhaps been best studied in the skin. The process can be divided into three overlapping but distinct phases: inflammation, new tissue formation and remodelling. If wound repair is functional, resolution/remodelling will result in restoration of the previous tissue architecture. In contrast, if resolution/remodelling fails, then pathological fibrosis (the replacement of tissue structure with scar) will occur (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Basic concept of wound healing and regeneration: injury, inflammation, new tissue formation and remodelling followed by resolution or pathological fibrosis.

Phase 1. Inflammation

During the first phase – inflammation – which occurs immediately after wounding, ongoing blood and fluid loss must be inhibited, host invasion by pathogens must be prevented and dead and dying cells removed. This process involves components of the coagulation cascade and immune system. The prime function of the coagulation cascade is to generate insoluble, cross-linked fibrin strands, which bind and stabilize weak platelet haemostatic plugs, formed at the site of injury (Chambers 2008). The formation of this provisional matrix (PM) predominately by passive leakage of serum factors from the local vasculature is critically dependent on the action of thrombin, a coagulation proteinase, which converts fibrinogen into fibrin. The PM is mostly composed of platelets, fibrin, fibronectin and vitronectin and formed in a tightly regulated process (reviewed in Mann et al. 2003; Zander et al. 2007; Chambers 2008). However, PM provides only a temporary barrier and scaffold for infiltrating immune system cells and must be removed during reepithelialization. All these processes occur after acute lung injury. Specifically, it has been shown that direct thrombin inhibition reduces lung collagen accumulation and connective tissue growth factor mRNA levels in a rat bleomycin lung fibrosis model (Howell et al. 2001). In another study, it was reported that increased local expression of coagulation factor X, a coagulation protease, contributes to the fibrotic response in human and murine lung injury (Scotton et al. 2009). Factor X was shown to drive fibrotic responses to lung injury by the activation of TGFβ and influencing fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. The authors also showed that in contrast to the assumption that it was only derived through microvascular leak, factor X is clearly derived from a local cellular source in murine bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis and provided the first evidence that it may be generated from the epithelium. An interesting study using fibrinogen-null mice showed that fibrin per se may not be required for progression to lung fibrosis after bleomycin exposure (Hattori et al. 2000). It was also shown that platelets are necessary for airway wall remodelling in a murine model of chronic allergic inflammation (Pitchford et al. 2004) although there is surprisingly sparse literature on the role of platelets in parenchymal lung fibrosis.

Neutrophils are among the first cells to appear at a wounded site. They are recruited by inflammatory signals released by damaged tissue cells and usually reach peak numbers within 48 h. Normally, neutrophils are cleared by undergoing apoptosis and removal by phagocytosis. It is thought that a sustained inflammatory insult primarily mediated by neutrophils is largely responsible for acute lung injury and the more fulminant acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Ware 2006). However, neutrophils may not be essential as ARDS can occur in neutropenic patients (Laufe et al. 1986). It was long thought that circulating blood monocytes are recruited later to the site of injury where they differentiated into macrophages. This view has been challenged in recent years. By direct examination of blood monocyte functions in vivo, it was shown that a subset of monocytes continuously patrols healthy tissues through long-range crawling on the resting endothelium (Auffray et al. 2007). This patrolling behaviour by a ‘resident’ monocyte population was required for rapid tissue invasion at the site of infection and the formation of newly differentiated tissue macrophages. In the lung specifically, an interesting cross-talk between monocytes and neutrophils has been reported. Using in vivo two-photon imaging, it was shown that depletion of blood monocytes impairs neutrophil recruitment to the lung specifically during transendothelial migration, thus revealing monocyte-dependent neutrophil recruitment during pulmonary inflammation (Kreisel et al. 2010). In addition, other studies have demonstrated a potential role for the chemokine receptor CCR2 in alveolar monocyte–dependent neutrophil migration in intact mice (Maus et al. 2002, 2003). Another study reported a role for lung-marginated Gr-1high monocytes in the development of stretch-induced pulmonary oedema during the pathophysiology of ventilator-induced lung injury (Wilson et al. 2009). Recently, in a human model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung injury, an early influx of a novel monocyte-like subpopulation into the lung was observed, accompanied by significantly increased neutrophil numbers (Brittan et al. 2012). In summary, these studies provide evidence in the lung that the neutrophil influx may be monocyte dependent and evidence for potential novel roles for monocyte-like subpopulations in lung injury.

Macrophages are thought to be important during later events in wound healing (Pollard 2009). The roles of both recruited and tissue-resident macrophages and their interactions with neutrophils during wound repair and regeneration are complex and not fully understood. Utilizing PU.1 null mice, which are genetically incapable of raising a classical inflammatory responses because of their lack of macrophages and functioning neutrophils, it was demonstrated that small sterile skin wounds were able to repair over a time course similar to that of wild-type siblings (Martin et al. 2003; Martin & Leibovich 2005). However, PU.1 null mice were much slower at clearance of cell and matrix debris at the wound site (Martin et al. 2003). Thus, in a clearly defined sterile environment, myeloid cells may not be critical for wound repair. This may not be applicable to complex organ injury and is unlikely to be the case in the presence of infection. In lung studies, both beneficial and adverse effects of macrophages during disease and wound healing have been described and are discussed in more detail later in this review.

Phase 2. New tissue formation

During the second phase – new tissue formation – cellular proliferation and migration of different cell types occur. Typically, this process begins 2–10 days after tissue damage and is initially characterized by the migration of neighbouring cells to the site of injury and the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis). Fibroblasts and macrophages contribute to the replacement of the PM to facilitate epithelial barrier restoration. During later stages of this phase, recruited fibroblasts are stimulated by macrophages and other cell types, via the archetypal profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, to differentiate into myofibroblasts, contractile cells that bring the edges of a wound together. Together with fibroblasts, myofibroblasts produce new, injury-associated extracellular matrix (ECM) mainly in the form of collagen but which can also include other components such as tenascin-C and ED-A fibronectin (FN) (Serini et al. 1998; Midwood et al. 2011). In the lung, it has been hypothesized that if the injury has not breached the integrity of the basement membrane, then the new ECM can be reabsorbed and eventually replaced with a normal ECM. If the basement membrane is irretrievably damaged, then scarring occurs and the newly secreted collagen forms the bulk of mature scar (Wallace et al. 2007). Less is known about detailed mechanisms of epithelial repair in the lung because of difficulties in establishing good in vivo models. Observations many decades ago, based on 3H-thymidine labelling during development and after rodent lung injury, suggested that the basal cell was the progenitor cell of the tracheal epithelium, the Clara cell provided this function in the distal airway, and type II pneumocytes proliferated and differentiated into type I pneumocytes in the alveoli during wound repair (Zander et al. 2007). Recent injury models and genetic approaches have confirmed many of these observations (reviewed in Zander et al. 2007; Crosby & Waters 2010).

Phase 3. Remodelling

The third phase – remodelling – is mainly characterized by the down-regulation of molecular processes initiated after tissue damage. This is followed by the restoration of normal tissue homoeostasis or replacement of normal tissue by fibrous or scar tissue. This phase typically begins 2–3 weeks after injury and can last for a considerable time. Most recruited cells undergo apoptosis or migrate from the site of injury during this process to leave behind a wound that mainly consists of collagen and other ECM components. Active remodelling of collagen by matrix metalloproteinases and remodelling of other components of the ECM may in some tissues finally restore tissue structure and function. Failure to do so can lead to persistent collagen production and pathological fibrosis. The concept of wound repair and regeneration is further reviewed elsewhere (Wallace et al. 2007; Gurtner et al. 2008; Crosby & Waters 2010).

Macrophages in wound healing

Origin and classification of macrophages

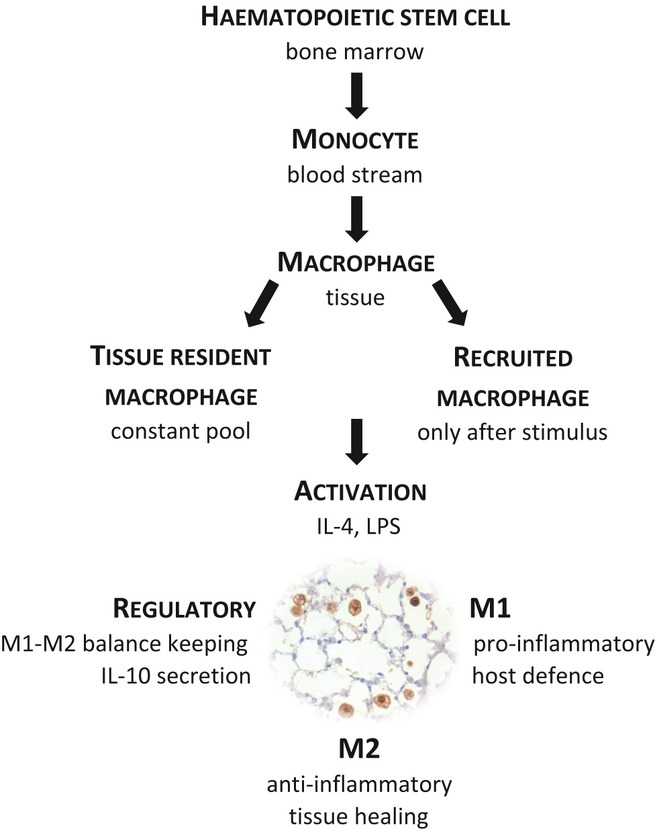

Macrophages, first described by Metchnikoff in the 1880s, are large mononuclear phagocytic cells. Traditionally, their predominant role has been considered in the context of host defence against environmental and innate injurious stimuli through their capacity as antigen-presenting cells and via their effector function in humoral and cell-mediated immunity (Geissmann et al. 2010). Increasingly however, they are considered pivotal in all aspects of tissue homoeostasis, and their diverse repertoire of functions is attributable to their remarkable plasticity (Mosser & Edwards 2008; Biswas & Mantovani 2010). Macrophage precursors are generated from committed haematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow (Geissmann et al. 2010). They are released into the blood stream as monocytes and differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells when migrating into tissues. Macrophages can be divided into two groups: tissue-resident and recruited macrophages. Tissue-resident macrophages form specialized subpopulations based on their anatomical location and locally produced microenvironmental factors. In contrast to recruited macrophages, which are thought to play key roles in acute inflammation, tissue-resident macrophages, including osteoclasts in the bone, Kupffer cells in the liver and alveolar macrophages in the lung, form a constant pool of cells that are integral to tissue homoeostasis (Pollard 2009; Murray & Wynn 2011).

Macrophage activation and phenotype

Independent of their location, macrophages can be further divided into functional groups based on their activation states (Mantovani et al. 2002; Fleming & Mosser 2011): M1 and M2 and the more recently described regulatory macrophages (Figure 2). This simplistic model of classification is a useful tool for considering macrophage phenotype, but clearly belies the true spectrum of macrophage activation states that must exist in situ. Broadly, M1 macrophages, also called classically activated macrophages, possess pro-inflammatory properties and mediate host defence against a variety of bacteria, protozoa and viruses. M2 macrophages, also called alternatively activated macrophages (Martinez et al. 2008; Gordon & Martinez 2010), possess anti-inflammatory functions and regulate wound healing. Regulatory macrophages secrete large amounts of IL-10, an essential and non-redundant anti-inflammatory cytokine with a crucial role in preventing inflammatory and autoimmune pathology (Fiorentino et al. 1991; Saraiva & O'Garra 2010; Murray & Wynn 2011).

Figure 2.

Classic concept of origin, classification and activation of macrophages.

Macrophage activation is predominantly dictated by a combination of innate immune receptors (pattern recognition receptors/PRRs) that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns and cytokine signalling. The archetypal classical activators of macrophages are LPS and interferon (IFN)-γ. The Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 are direct inducers of alternative activation. Other cytokines such as IL-33, IL-25 and IL-21 amplify alternative activation indirectly (Gordon & Martinez 2010). In peripheral blood monocyte–derived macrophage culture systems, M-CSF is typically used to drive alternative induction and GM-CSF to drive classical induction. Expression markers, or phenotypic signatures, for murine macrophage activation states are now well described. They include gene expression changes in arginase-1, YM-1 and YM-2, Fizz-1 and the mannose receptor for alternative, and IL-12p40 and iNOS for classical activation (Gordon & Martinez 2010). In contrast, the phenotypic signature of human macrophage activation states is poorly defined. Recently described candidates that imply alternative activation are CD163, haeme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), folate receptor β and the CC chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18) (Puig-Kroger et al. 2009; Gordon & Martinez 2010; Sierra-Filardi et al. 2010; Schraufstatter et al. 2012).

The molecular mechanisms that are involved in macrophage activation and phenotypic plasticity are still not fully understood. The importance of IFN-γ and IL-4/IL-13 in dictating macrophage phenotype might indicate that T cells are crucial in this regard. However, it was shown that macrophage phenotypes do not depend on the presence of T or B lymphocytes as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice have inducible M1 and M2 populations (Mills et al. 2000). In addition to classic Th1 and Th2 signalling, other potential mechanisms that may be involved in M1–M2 phenotype decision making include prolyl hydroxylase (PHD), resolvin D1 and serum amyloid signalling pathways, and epigenetic mechanisms (Serhan et al. 2008; Murray et al. 2010; Takeda et al. 2011; Takeuch & Akira 2011; Titos et al. 2011). In this context, inflammasome effector mechanisms should also be mentioned as they are an important area of fruitful investigation. Inflammasomes are intracellular multiprotein complexes that orchestrate immune responses via proximity-induced autoactivation of caspase 1 and the release of several soluble factors that contribute to both Th1- and Th2-related immune responses. Inflammasome-mediated signalling has been shown to occur in macrophages as well as several other cell types and may contribute to both M1 and M2 macrophage activation (reviewed in Lamkanfi 2011).

Clearly, while phenotypic signatures of macrophage subtypes are useful for classification, it is the functional characteristics of macrophages that dictate their role in health and disease.

The alternatively activated macrophage in wound healing

It is generally believed that macrophages are important regulators in wound healing, although they may not be essential in all settings as shown in PU.1 mice where healing of small sterile skin wounds still occurs in their absence (Martin et al. 2003). M2 macrophages possess anti-inflammatory functions and are believed to orchestrate tissue healing processes, whereas M1 macrophages mainly respond to acute inflammation. Clearly, both M1 and M2 macrophages are likely to be important during the dynamic process of wound healing, but herein we now focus on the role of M2 macrophages after initiation of inflammation.

In helminth infection, a global burden of disease in man, murine studies have established that Th2-type responses and M2 macrophage activation are essential in limiting acute tissue damage and resolution of tissue damage during experimental worm infection (Jenkins et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012). However a ‘switch’ to an M2 phenotype is not necessarily beneficial to the host in the context of chronic bacterial infection. Several studies have demonstrated that a ‘common host response’ of macrophages to bacterial infections coincides with an M1 macrophage signature using gene expression analysis as reviewed in the study of Benoit et al. 2008. The persistence of bacterial infections and the chronic evolution of infectious diseases are linked to macrophages reprogramming towards heterogeneous M2 signatures and may involve mechanisms developed by bacterial pathogens to promote M2 polarization (Benoit et al. 2008).

M2 macrophages make a wide range of factors that could be involved in functional and/or pathological remodelling, leading either to restoration of normal tissue function or to pathological fibrosis and tissue dysfunction. These factors include arginase-1, CCL18, TGF-β and IL-10 (reviewed in Gurtner et al. 2008; Gordon & Martinez 2010). The l-arginine metabolism plays a central role in M1 vs. M2 macrophage signalling. In contrast to M1 macrophages in which an increased nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity results in increased NO production and bacterial killing, in M2 macrophages, an increased arginase-1 and decreased NOS activity result ultimately in the production of polyamides, molecules that induce cell proliferation, or proline, the basic building block of collagens, promoting tissue repair (Varin & Gordon 2009). CCL18 was recently shown to cause maturation of cultured human monocytes to macrophages in the M2 spectrum as well as being secreted by M2 macrophages themselves, which may contribute to pathological processes (Pechkovsky et al. 2010; Schraufstatter et al. 2012). The detailed mechanisms of TGF-β and IL-10 signalling in driving tissue healing or pathological processes are less well understood even after intense research and seem to be highly dependent on microenvironmental factors at the site of injury. IL-10 was shown to be produced by a wide range of cells, including enhanced secretion in M2 macrophages, and to be an important anti-inflammatory cytokine in the development and regulation of a variety of immune responses, including both Th1 and Th2 immune responses (reviewed in Saraiva & O'Garra 2010). The roles of TGF-β in fibroblast differentiation are described later in this review. Because of this marked plasticity, M2 macrophages have sometimes been subdivided into M2a, M2b and M2c macrophages depending on their functional properties.

During remodelling, M2 macrophages, in concert with neighbouring epithelial and mesenchymal cells, produce a panel of growth factors that stimulate fibroblasts and epithelial proliferation. These include epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands and TGFβ1. In an in vivo porcine model, it was shown that EGF-like cytokine treatments of skin wounds transiently supplied with ErbB3 receptors can generate an additive beneficial outcome (Okwueze et al. 2007). Macrophage-derived TGFβ1 contributes to wound repair and regeneration by promoting fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, by enhancing expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, such as MMP 1, MMP 9 and MMP 12, which are associated with lung disease (Churg et al. 2012), and by directly stimulating the synthesis of interstitial fibrillar collagens in myofibroblasts (Roberts et al. 1986; Murray & Wynn 2011). M2 macrophages secrete several other factors that control ECM turnover and cytokines that recruit fibroblasts and immune cells (reviewed in Imai et al. 1999; Curiel et al. 2004; Wynn 2008; Kis et al. 2011; Murray & Wynn 2011). They also phagocytose dead and dying cells and cellular debris, which inhibits inflammation. It was also shown that macrophages seem to produce a wide range of collagens (Schnoor et al. 2008). The significance of collagen production by macrophages remains unknown but again may contribute to the type of repair process that follows injury. M2 macrophages produce factors that induce myofibroblast apoptosis, can serve as antigen-presenting cells and express immunoregulatory proteins such as IL-10, Fizz-1 and arginase-1, which are known to decrease inflammatory processes and promote wound healing and remodelling (Gabbiani 2003; Reese et al. 2007; Pesce et al. 2009; Herbert et al. 2010; Murray & Wynn 2011). The balance between all these functions likely determines whether a particular injury results in functional or pathological repair.

The alternatively activated macrophage – studies in the lung

Observations made in a variety of animal models, and to a lesser extent in man, have provided insights into the potential significance of alternatively activated macrophages in lung disease. Having described their presence, some of the most elegant studies have sought to define the potential source of M2 macrophages and their functional role in disease progression.

The source of M2 macrophages in lung disease

The origin of potential ‘wound-healing’ M2 macrophages after an injurious stimulus, tissue resident or recruited, has attracted controversy. It was widely assumed that tissue-resident macrophages play a less important role during acute injury. It was believed that the primary response to an injurious stimulus and acute inflammation initiates massive recruitment of new monocytes from the blood stream rather than proliferation of tissue-resident macrophages and that these newly recruited monocytes differentiate into both M1 (pro-inflammatory, tissue destructive) and M2 (anti-inflammatory, tissue healing) macrophages. However, this view was challenged in recent studies within the pleural cavity, a model often used to study leucocyte infiltration. In a murine model of helminth infection, which normally results in functional repair, it was convincingly shown that massive local M2 macrophage proliferation in the pleural cavity driven by IL-4 secretion from Th2 cells is sufficient to expel worms (Jenkins et al. 2011). Thus, the authors propose an alternative mechanism of inflammation that allows resident macrophages to accumulate in sufficient numbers to perform critical functions such as parasite sequestration and wound repair in the absence of new cell recruitment. In addition, it was shown in the pleural cavity that a quantifiable proliferative burst of tissue macrophages restores homoeostatic macrophage populations after acute inflammation (Davies et al. 2011). The implication is that local proliferation may be a general mechanism for the self-sufficient renewal of tissue macrophages during development and acute inflammation and not one restricted to non-vascular tissues. The significance of either mechanism in response to parenchymal lung damage followed by acute inflammation and functional or pathological repair, as opposed to disease modelled in the pleural space, remains to be elucidated.

In a lung fibrosis model, it was shown that depletion of circulating monocytes, defined as Ly6Chi, CCR21+, CX3CR12-, led to reduced expression of intrapulmonary M2 macrophages and reduced fibrosis, while adoptive transfer of Ly6Chi monocytes into the circulation enhanced intrapulmonary M2 expression and lung fibrosis (Gibbons et al. 2011). However, the mechanism of this potential cross-talk between monocytes and the lung remains unknown. Interesting in this context, another lung study analysing gene transcription changes related to cell traffic in primary murine monocytes and their lung descendants, lung macrophages and lung dendritic cells showed that alveolar macrophages stepwise down-regulate gene expression relevant to cell traffic and strongly up-regulate a distinct set of matrix metallopeptidases potentially involved in tissue invasion and remodelling (Zaslona et al. 2009).

The function of M2 macrophages in lung disease

Before describing studies of M2 macrophages in lung disease, it is worthwhile revisiting the phenotype of the alveolar macrophage in the healthy state. Alveolar macrophages, in keeping with other tissue-resident macrophages, possess a relative M2 phenotype in the ‘resting’ state because of their roles in tissue homoeostasis. Human alveolar macrophages secrete CCL18 and IL-10, and it is their contact with the alveolar epithelium that maintains them in a restrained anti-inflammatory phenotype through interaction of CD200, IL-10 and TGF-β (reviewed in (Herold et al. 2011). The alveolar epithelium is a key modulator of inflammatory responses, with the capacity to release a wide range of cytokines and chemokines, but also generating lipids and peptide mediators and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that enhance the infiltration of the lung airspace with leucocytes (Tesfaigzi 2006). Perturbation of the alveolar macrophage–alveolar epithelium contact is considered a critical event in early inflammatory signalling and therefore in wound healing and regeneration. The detailed role of the alveolar epithelium and its putative interaction with macrophages are extensively reviewed in the studies of Tesfaigzi 2006; Crosby & Waters 2010.

The role of M2 macrophages has been studied, among others, in lung fibrosis and asthma. The multifactorial nature of asthma results in the involvement of complex cytokine networks with both beneficial and adverse effects during disease progression. These effects include the activation of both M1 and M2 macrophages. M2 macrophages have roles in the repair of the damaged lung, but the persistence of these cells also contributes to the excessive production of profibrotic factors that is linked to airway remodelling, which characterizes chronic asthma (Moreira & Hogaboam 2011; Moreira et al. 2011). It was shown that alveolar macrophages from asthmatic patients produce higher levels of IL-13 compared to macrophages from healthy volunteers (Prieto et al. 2000) and that allergic alveolar macrophages have impaired production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12 (Magnan et al. 1998), all characteristics of M2 macrophages. M1 macrophages may be involved in the exacerbation of the allergic inflammatory response during acute asthma (Moreira & Hogaboam 2011).

The interstitial lung diseases encompass a large number of disorders characterized by varying degrees of inflammation, remodelling and progressive parenchymal fibrosis. Among the commonest are sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), but neither disease can be readily modelled in rodents. However, studies in the bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model have shed light on potential mechanisms of wounding and repair in the lung. Intratracheal administration of the antibiotic bleomycin results in resolvable lung fibrosis, which allows for the dissection of pathways that might be useful in determining what drives functional rather than pathological repair processes in the lung. The bleomycin model can be divided into three phases: inflammation, remodelling and recovery. Typically, the administration of bleomycin induces a strong initial inflammatory response in the lung, which is followed by the onset of fibrosis and subsequent resolution. The bleomycin animal model and various treatment strategies were extensively reviewed in the study of Moeller et al. 2008. The role of macrophages during all three phases of the murine bleomycin model has been reported (Gibbons et al. 2011). Using macrophage/monocyte depletion strategies, it was shown that fibrosis is independent of monocytes and lung macrophages during the inflammatory phase of the model. A significant reduction in lung macrophages during this phase by administration of liposomal clodronate did not have any effect on fibrosis. In contrast, the study demonstrated that lung macrophages regulate the fibrotic phase of the model. It was shown that depletion of lung macrophages during this phase significantly reduced the degree of pulmonary fibrosis. Further, the ‘profibrotic’ properties could be linked to a M2 macrophage phenotype using YM-1 and arginase-1 as markers. Interestingly, depletion of lung macrophages during the recovery phase of the model slowed down the resolution of fibrosis, demonstrating a beneficial effect of macrophages during this phase. A beneficial role of macrophages during recovery was also shown in a model of resolvable liver fibrosis (Duffield et al. 2005). In addition, it was shown that milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 (Mfge8) diminishes the severity of tissue fibrosis in mice by binding and targeting collagen for uptake by macrophages (Atabai et al. 2009).

Observational studies in humans have described the presence of M2 macrophages in lung disease. Alveolar macrophage expression of CD163, a human M2 macrophage marker, was shown to be enhanced in patients with IPF compared to controls (Gibbons et al. 2011). Another study showed that M2 macrophages are a prominent feature of lung fibrosis and linked it to a marked increase in gene expression and protein levels of CCL18 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and BAL-derived cells (Prasse et al. 2006). Recombinant CCL18 was shown to enhance maturation of cultured human monocytes from blood to M2 macrophages (Schraufstatter et al. 2012). CCL18 is also increasingly recognized as a promising biomarker for IPF (reviewed in Bargagli et al. 2011). Another study suggests an important role for M2 alveolar macrophages in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis and indicates that both IL-4 and IL-10 account for human M2 macrophage phenotype activation in patients with fibrotic interstitial lung disease using CCL17, CCL18, CCL22, IL1-RA and CD206 as M2 macrophage markers (Pechkovsky et al. 2010). In sarcoidosis, a systemic Th1 inflammatory disease primarily affecting the lung, one study reported no evidence of altered alveolar macrophage polarization, but reduced expression of TLR2, in BAL cells (Wiken et al. 2010).

Conclusion

Many of the generic features of wounding and repair occur in the context of lung injury. There is a body of evidence that suggests a central role for macrophages in wound healing. A spectrum of macrophage phenotypes is likely to exist in the dynamic process of tissue repair, but there is specific evidence that alternatively activated (M2) macrophages possess anti-inflammatory, potential ‘wound-healing’ functions and therefore have the capacity to contribute in many ways to tissue healing. However, their role may be ‘context specific’, and observational and experimental data suggest that M2 macrophages, or further specific subtypes, also play pathological roles, for example, in the development of lung fibrosis. Manipulating M2 macrophages may have therapeutic value, but further mechanistic studies are required to better define the signals that drive alternative activation, the temporal association between M2 expression and disease progression and the functional plasticity within macrophage subsets.

Funding

Andreas Alber (AA) is supported through a joint British Lung Foundation/Medical Research Council (BLF/MRC) PhD studentship.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Reference

- Atabai K, Jame S, Azhar N, et al. Mfge8 diminishes the severity of tissue fibrosis in mice by binding and targeting collagen for uptake by macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:3713–3722. doi: 10.1172/JCI40053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargagli E, Prasse A, Olivieri C, Muller-Quernheim J, Rottoli P. Macrophage-derived biomarkers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Med. 2011;2011:717130. doi: 10.1155/2011/717130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit M, Desnues B, Mege JL. Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. J. Immunol. 2008;181:3733–3739. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittan M, Barr L, Conway MA, et al. A novel subpopulation of monocyte-like cells in the human lung after LPS inhalation. Eur. Respir. J. 2012 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00113811. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RC. Procoagulant signalling mechanisms in lung inflammation and fibrosis: novel opportunities for pharmacological intervention? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S367–S378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Liu Z, Wu W, et al. An essential role for TH2-type responses in limiting acute tissue damage during experimental helminth infection. Nat. Med. 2012;18:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nm.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churg A, Zhou S, Wright JL. Matrix metalloproteinases in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;39:197–209. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00121611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby LM, Waters CM. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010;298:L715–L731. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00361.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies LC, Rosas M, Smith PJ, Fraser DJ, Jones SA, Taylor PR. A quantifiable proliferative burst of tissue macrophages restores homeostatic macrophage populations after acute inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J. Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming BD, Mosser DM. Regulatory macrophages: setting the threshold for therapy. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2498–2502. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J. Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons MA, Mackinnon AC, Ramachandran P, et al. Ly6Chi monocytes direct alternatively activated profibrotic macrophage regulation of lung fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;184:569–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1719OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori N, Degen JL, Sisson TH, et al. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in fibrinogen-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:1341–1350. doi: 10.1172/JCI10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert DR, Orekov T, Roloson A, et al. Arginase I suppresses IL-12/IL-23p40-driven intestinal inflammation during acute schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 2010;184:6438–6446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold S, Mayer K, Lohmeyer J. Acute lung injury: how macrophages orchestrate resolution of inflammation and tissue repair. Front. Immunol. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell DC, Goldsack NR, Marshall RP, et al. Direct thrombin inhibition reduces lung collagen, accumulation, and connective tissue growth factor mRNA levels in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:1383–1395. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Nagira M, Takagi S, et al. Selective recruitment of CCR4-bearing Th2 cells toward antigen-presenting cells by the CC chemokines thymus and activation-regulated chemokine and macrophage-derived chemokine. Int. Immunol. 1999;11:81–88. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, et al. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 2011;332:1284–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1204351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis K, Liu X, Hagood JS. Myofibroblast differentiation and survival in fibrotic disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2011;13:e27. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisel D, Nava RG, Li W, et al. In vivo two-photon imaging reveals monocyte-dependent neutrophil extravasation during pulmonary inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18073–18078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008737107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M. Emerging inflammasome effector mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nri2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufe MD, Simon RH, Flint A, Keller JB. Adult respiratory distress syndrome in neutropenic patients. Am. J. Med. 1986;80:1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90659-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnan A, van PD, Bongrand P, Vervloet D. Alveolar macrophage interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-12 production in atopic asthma. Allergy. 1998;53:1092–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann KG, Brummel K, Butenas S. What is all that thrombin for? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:1504–1514. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Leibovich SJ. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, D'Souza D, Martin J, et al. Wound healing in the PU.1 null mouse–tissue repair is not dependent on inflammatory cells. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1122–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus U, von GK, Kuziel WA, et al. The role of CC chemokine receptor 2 in alveolar monocyte and neutrophil immigration in intact mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;166:268–273. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus UA, Waelsch K, Kuziel WA, et al. Monocytes are potent facilitators of alveolar neutrophil emigration during lung inflammation: role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3273–3278. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midwood KS, Hussenet T, Langlois B, Orend G. Advances in tenascin-C biology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:3175–3199. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0783-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J. Immunol. 2000;164:6166–6173. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40:362–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira AP, Hogaboam CM. Macrophages in allergic asthma: fine-tuning their pro- and anti-inflammatory actions for disease resolution. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:485–491. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira AP, Cavassani KA, Ismailoglu UB, et al. The protective role of TLR6 in a mouse model of asthma is mediated by IL-23 and IL-17A. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4420–4432. doi: 10.1172/JCI44999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LA, Rosada R, Moreira AP, et al. Serum amyloid P therapeutically attenuates murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via its effects on macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okwueze MI, Cardwell NL, Pollins AC, Nanney LB. Modulation of porcine wound repair with a transfected ErbB3 gene and relevant EGF-like ligands. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:1030–1041. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechkovsky DV, Prasse A, Kollert F, et al. Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin. Immunol. 2010;137:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Wilson MS, et al. Retnla (relmalpha/fizz1) suppresses helminth-induced Th2-type immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000393. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchford SC, Riffo-Vasquez Y, Sousa A, et al. Platelets are necessary for airway wall remodeling in a murine model of chronic allergic inflammation. Blood. 2004;103:639–647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasse A, Pechkovsky DV, Toews GB, et al. A vicious circle of alveolar macrophages and fibroblasts perpetuates pulmonary fibrosis via CCL18. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:781–792. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1518OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto J, Lensmar C, Roquet A, et al. Increased interleukin-13 mRNA expression in bronchoalveolar lavage cells of atopic patients with mild asthma after repeated low-dose allergen provocations. Respir. Med. 2000;94:806–814. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Kroger A, Sierra-Filardi E, Dominguez-Soto A, et al. Folate receptor beta is expressed by tumor-associated macrophages and constitutes a marker for M2 anti-inflammatory/regulatory macrophages. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9395–9403. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese TA, Liang HE, Tager AM, et al. Chitin induces accumulation in tissue of innate immune cells associated with allergy. Nature. 2007;447:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature05746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:4167–4171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M, O'Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoor M, Cullen P, Lorkowski J, et al. Production of type VI collagen by human macrophages: a new dimension in macrophage functional heterogeneity. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5707–5719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufstatter IU, Zhao M, Khaldoyanidi SK, Discipio RG. The chemokine CCL18 causes maturation of cultured monocytes to macrophages in the M2 spectrum. Immunology. 2012;135:287–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotton CJ, Krupiczojc MA, Konigshoff M, et al. Increased local expression of coagulation factor X contributes to the fibrotic response in human and murine lung injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:2550–2563. doi: 10.1172/JCI33288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serini G, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Ropraz P, et al. The fibronectin domain ED-A is crucial for myofibroblastic phenotype induction by transforming growth factor-beta1. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:873–881. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Filardi E, Vega MA, Sanchez-Mateos P, Corbi AL, Puig-Kroger A. Heme Oxygenase-1 expression in M-CSF-polarized M2 macrophages contributes to LPS-induced IL-10 release. Immunobiology. 2010;215:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieter RM. What differentiates normal lung repair and fibrosis? Inflammation, resolution of repair, and fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008;5:305–310. doi: 10.1513/pats.200710-160DR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Costa S, Delamarre E, et al. Macrophage skewing by Phd2 haplodeficiency prevents ischaemia by inducing arteriogenesis. Nature. 2011;479:122–126. doi: 10.1038/nature10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuch O, Akira S. Epigenetic control of macrophage polarization. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2490–2493. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaigzi Y. Roles of apoptosis in airway epithelia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006;34:537–547. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0014OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titos E, Rius B, Gonzalez-Periz A, et al. Resolvin D1 and its precursor docosahexaenoic acid promote resolution of adipose tissue inflammation by eliciting macrophage polarization toward an M2-like phenotype. J. Immunol. 2011;187:5408–5418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varin A, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: immune function and cellular biology. Immunobiology. 2009;214:630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace WA, Fitch PM, Simpson AJ, Howie SE. Inflammation-associated remodelling and fibrosis in the lung – a process and an end point. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2007;88:103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;27:337–349. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiken M, Idali F, Al Hayja MA, Grunewald J, Eklund A, Wahlstrom J. No evidence of altered alveolar macrophage polarization, but reduced expression of TLR2, in bronchoalveolar lavage cells in sarcoidosis. Respir. Res. 2010;11:121. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MR, O'Dea KP, Zhang D, Shearman AD, van RN, Takata M. Role of lung-marginated monocytes in an in vivo mouse model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;179:914–922. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-877OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander DS, Popper H, Jagirdar J, Haque A, Cagle PT, Barrios R. Molecular Pathology of Lung Diseases. 1st edn. Springer Science+Business Media, Inc: New York, NY; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslona Z, Wilhelm J, Cakarova L, et al. Transcriptome profiling of primary murine monocytes, lung macrophages and lung dendritic cells reveals a distinct expression of genes involved in cell trafficking. Respir. Res. 2009;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]